Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part II on the Criterion Channel

For Yuri Tsivian

DB here:

Everyone knows Eisenstein as a theorist and practitioner of something called montage, which in his hands comes to mean a lot of things. But he was no less interested in what he called expressive movement. He believed that the viewer could be aroused by dynamic physical action that carried powerful feeling. Expressive movement pervades the set-pieces of his silent films. On the Odessa Steps of 1925’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), we get the robotic descent of the Cossacks opposed to the agitated flight of the citizenry, and the street massacre of October (1927) makes even mechanical bridges seem ferocious. And less flamboyant moments, from the animalistic antics of the spies in Strike to the weeping masses at the Odessa quai, are full of expressive postures, gestures, and facial behavior. Eisenstein sculpts the human body so as to project extreme states of feeling.

That effort is on full display in Ivan the Terrible Part II, which I discuss in our current entry on FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel. My commentary, grounded in a single sequence, builds on an analysis I offered in my book The Cinema of Eisenstein, but the clever experts at Criterion have created dynamic juxtapositions through cuts and replays that I couldn’t summon up in print. I try to show how, as ever, Eisenstein sacrifices bland realism of behavior to something more sharp and intense. In this “theatrical” film, he goes beyond line readings to offer maniacally heightened physical action–a sort of deadly serious, amped-up, live-action cartoon. Eisenstein worshipped Disney, after all.

Today’s blog entry bounces off that installment to show the connection between expressive movement and the most banal stock-in-trade of cinema: the standard scene of two people talking to each other.

Lessons with the master

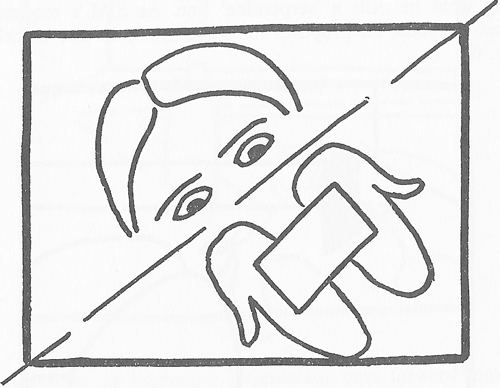

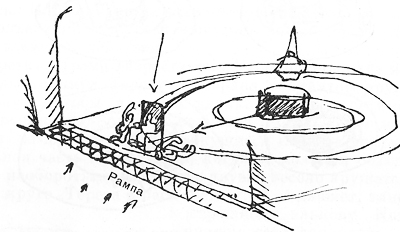

A sketch from Eisenstein’s lectures on Crime and Punishment.

Eisenstein’s silent films seek a “dramaturgy of film form” that would surpass traditions of theatrical and novelistic storytelling. This mission, which creates a sort of epic cinema, left an odd gap. From Strike (1925) to Old and New (1929), his films are notably lacking in one stock ingredient. He seldom creates sustained scenes showing a developing conflict between two characters in an ordinary setting–a parlor or office or street. With few exceptions, Eisenstein “explodes” even standard scenes by cutting to action elsewhere. The factory owners of Strike chortle over drinks while, thanks to parallel montage, the workers are rounded up by soldiers on horseback.

Other Soviet Montage directors were willing to work up theatrical scenes: Pudovkin has a Hitchcockian suspense sequence in Mother (1926), while Kuleshov turns the second stretch of By the Law (1926) into a Kammerspiel. But Eisenstein’s urge to splinter face-to-face dramaturgy came from a different sense of theatre–that “Theatricalism” of his teacher Meyerhold, who saw the stage not as the copy of a real space but as an arena for performance. Eisenstein extended this idea by thinking of the shot and the sequence as an arena for action, specifically expressive movement.

By the 1930s, Eisenstein may have sensed that sound cinema would make films more theatrical in a traditional sense. Sequences would be more concentrated in one locale and focused on a few characters. Crosscutting, a mainstay of silent film, would become rarer. He accordingly began to ponder creative ways of filming two-handers. In his courses at the Soviet film school VGIK he explored ways to intensify dramatic face-offs without interruptive cutting.

These lectures are inspiring because they show you a filmmaker thinking through problems and tracing how one solution leads to new problems. A soldier returns from the war to find his wife pregnant with another man’s child. With his students Eisenstein spent weeks scrutinizing options for performance, shooting, and cutting this simple situation. A banquet is held for Dessalines, Haitian hero. How do you film his realization that his hosts are planning to kill him? How do you present the bedroom of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, or the claustrophobic apartment of Thérèse Raquin? How do you stage Raskolnikov’s murder of the pawnbroker in Crime and Punishment…and do it in one fixed shot? (You don’t hear much about Eisenstein the long-take man.)

The results of this line of thinking show up in his films. Alas, we have only glimpses in what remains of Bezhin Meadow (finished 1937; banned, now lost). And Alexander Nevsky (1938), still conceived on a broad canvas, doesn’t really face up to the demands of intimate scenes. It’s only in both parts of Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1946) that we can see how Eisenstein plunged into doing what most directors do: filming uninterrupted scenes of people talking to one another.

Needless to say, he doesn’t do it the way they do.

The tsar in your lap

Expressive movement is involved, but so too are other stylistic strategies. For one thing, Eisenstein rethinks analytical editing. Characters need not face one another; they can be turned to the viewer and interact by shifting their eyes. No need for over-the-shoulder reverse angles either; you can cut in or out along the camera axis. Both strategies are introduced at the start of Ivan the Terrible Part I.

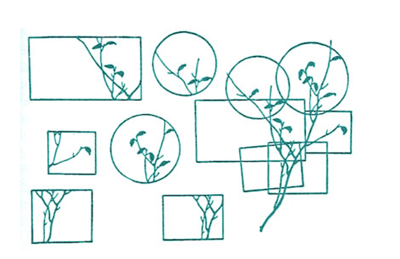

More elaborately, Eisenstein may dissect a scene through what he called in his VGIK classes the “montage unit” (uzel), a cluster of shots taken from roughly the same orientation. These yield chunks of space that overlap when edited together. He diagrammed this procedure in an illustration of cherry blossoms he found in a Japanese drawing manual.

This collage of overlapping bits, anticipating Hockney’s photo paste-ups, is actualized on film in the Pskov sequence of Ivan Part I, as I discuss in my book.

Another strategy is the use of depth. While Renoir, Welles, William Cameron Menzies, and other directors were trying out deep-space staging and depth of camera focus, so was Eisenstein. Well before Welles, he and his Soviet colleagues offered grotesque wide-angle shots. Below, Old and New and China Express (Ilya Trauberg, 1929).

More rigorously, Eisenstein began to think of how to arrange his scenes along the camera axis. True, a great many of his scenes are staged laterally, with figures arrayed from left to right.

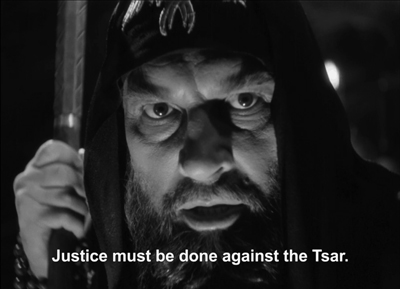

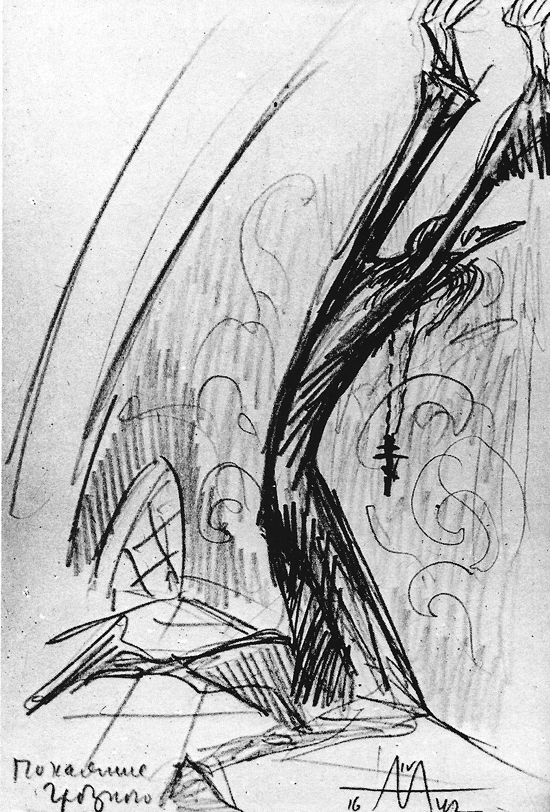

But others, particularly those at a dramatic pitch, are staged in depth. And what distinguishes Eisenstein, to my mind, is a strikingly confrontational or immersive approach. You can see it emerging in the VGIK exercises, notably in his stage designs for a hypothetical production of Thérèse Raquin. Here the paralyzed, speechless Madame Raquin terrorizes the murderous lovers with her glittering eyes. Eisenstein wanted the actors to perform on a turntable that would show her chair rotating to spy on the couple’s affair from different vantage points. At the climax, when the guilty lovers commit suicide, Madame Raquin’s chair was to break from the circle and propel itself forward, so that she would be staring furiously into the audience.

The footlights, marked with arrows, indicate that the effect is exaggerated by horror-style lighting from below.

This effect might look gimmicky, a sort of stage equivalent for what we can easily accomplish in cinema. Don’t directors often heighten the drama by making their actors advance to the camera? But in many scenes Eisenstein moves his players toward us, then cuts further backward, letting axial cuts create an unfolding foreground. A new playing space is opened up, and the actor is free, or rather compelled, to thrust further forward, sometimes into uncomfortably big close-up.

The Soviets called axial cuts “concentration cuts,” and we mostly find them used to enlarge, usually shockingly, something far off. But Eisenstein creates something more risky.“In my work,” he wrote, “set designs are inevitably accompanied by the unlimited surface of the floor in front of it, allowing the bringing forward of unlimited separate foreground details.” In principle the camera can back up again and again, and the foreground could unfold forever.

The result sometimes yields direct address, as in my Criterion Channel example, but more generally it creates a sense of characters passionately engaged in clamping their will upon others and hurling themselves not just at one another but at us. Characters confide in the camera, and–long before all today’s talk of “immersive” cinema–the camera is us.

The short lesson is that we still have a lot to learn from Eisenstein–and his films. Apart from opening up new vistas of cinema, they offer thrilling experiences. Ivan Part II, subtitled “The Boyars’ Plot,” is a dark Jacobean drama of bloody revenge and betrayal. It’s twisted enough to satisfy any connoisseur of palace intrigue. It’s also brilliantly weird as cinema. Once more the Old Man comes through.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment, which was a bit tougher than usual. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson, and to Masha Belodubrovskaya for translation help. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

The best source for Eisenstein’s VGIK classes remains Vladimir Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein, my pick for one of the top ten film books ever published. Direction, Volume 4 of Eisenstein’s Selected Works in Six Volumes (Izbrannie proizvedeniia v shesti tomakh, 1964-1969) is the source of other examples I use here, including Thérèse Raquin, from p. 622.

Of the immense literature on Eisenstein, I especially recommend Yuri Tsivian’s monograph on Ivan the Terrible in the BFI series. Yuri also provided a wonderful video essay for the Criterion DVD release, now unhappily out of print. Kristin wrote a whole book on Ivan: Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis.

I discuss Eisenstein as an action director in an earlier entry. On axial cuts in Eisenstein and others, go here; Kurosawa’s use of them is discussed here.

Hockney’s photomontage Mother 1 is from 1985.

Also, too: I noted earlier that my book On the History of Film Style has gone out of print. An e-book edition, with updates and color images, is nearing completion. I hope to offer a pdf to you soon. Yes, Eisenstein is involved.

Eisenstein sketch: Ivan pleading for mercy in the Last Judgment, planned for Part III of the film.

The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929)

DB here:

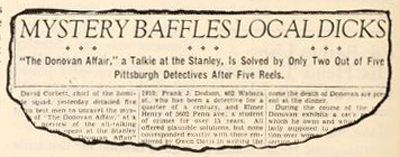

The Donovan Affair was Columbia’s first all-talking picture, and Frank Capra’s as well. We discussed it a little in an entry devoted to a Cinema Ritrovato retrospective of Capra’s films. The film lacked, and still lacks, a soundtrack, which may be lost.

The Donovan Affair is an unusually fluid early talkie, and that led me to speculate we might be seeing the silent release version. Wrong! It really does survive only as a sound film without a soundtrack; the Library of Congress print I studied last month has a leader labeled “synchronized version.”

The clunky plot didn’t improve on repeated viewing, but the film did teach me some things about those transitional years 1928-1932, when filmmakers were figuring out how to make a sound feature. I thought I’d share some of those findings with you today.

But I must warn you that there’s one big spoiler coming up. I tell you whodunit. It’s necessary to make a point, but I will warn you just before the offending paragraph, so you can skip if you wish.

Blood-spattered footlights

Murder ran wild on the Anglo-American stage of the 1920s. While melodramas of love and betrayal waned, mysteries rose in popularity. There were plays about gangsters, trials, and domestic homicide. There were comedies of lethal intrigue in spooky settings, like The Bat (1920), The Last Warning (1922), and The Cat and the Canary (1922). A little more seriously, in response the rise of the genteel British detective novel (Christie, Sayers, Allingham et al.), there emerged plays that dumped murder into society drawing rooms.

You know the format. The setting is typically a mansion, with portraits, plush salons, and an impressive library. The victim, usually a bounder, deserves killing. The suspects are both high and low: businessmen, doctors, lawyers, dowagers, flappers, playboys, ne’er-do-wells, gangsters, and servants. Into this ménage steps a police inspector, often with a bumbling assistant, who will more or less skillfully reveal the culprit. In the process, though, someone else is likely to die.

The prototype is Bayard Veiller’s play The Thirteenth Chair (1916), but by the 1920s Britain and the US produced a host of popular and well-reviewed drawing-room mysteries: The Nightcap (1920), In the Next Room (1923), The Creaking Chair (1924), Interference (1927), The Man at Six (1928), The Clutching Claw (1928), and The Canary Murder Case (1928). The most famous entry in this cycle is probably Patrick Hamilton’s Rope (1929), which stands out because it presents the crime from the killers’ viewpoint. The question isn’t “Who did it?” but “Will they get away with it?” Rope’s “inverted” structure (no pun intended; it’s a trade term) was anticipated by A. A. Milne’s The Fourth Wall (1928).

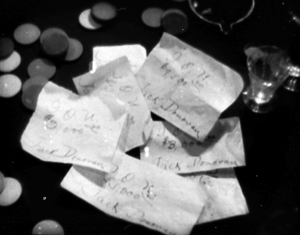

Owen Davis’s play The Donovan Affair (1926) fits snugly into this cycle. The action starts with Inspector Killian and his assistant Carney ushering the suspects into the Rankin family library. The rakish Jack Donovan has been murdered at a birthday dinner. The circumstances are odd: To demonstrate a glowing ring Donovan wears, the lights were turned out. In the darkness, he was stabbed with a carving knife.

Most of those at the table have good reason to kill Donovan. He was having affairs with married women and had an eye on Rankin’s daughter Jean, whom David hoped to marry. The first act is centered on exposition that emerges from Killian’s questioning of the guests. One, Horace Carter, comes forward to declare he knows who the killer is, because the victim’s missing ring was slipped into his pocket. Killian doubts that the ring could have been visible, and so the lights are switched off a second time as a test. Bad idea: When the lights come back on, Horace has been stabbed with the same knife. Score one for law and order. Later one character will shoot another as Killian looks on.

The next two acts expose more motives, lay false trails (David has brought a gun to dinner and has blood on his cuff), and string out physical clues, including a fake ring and some threatening letters to Donovan. In frustration, Killian leaves the suspects to pool their information, in hopes that they’ll discover the killer. Once more the lights are put out to allow the culprit to replace the ring and a missing letter. The killer is revealed, and there’s a struggle in semidarkness. Killian and his men burst in to seize the guilty party.

Among all this claptrap, the blackout gimmick is worked very hard. Bayard Veiller’s Thirteenth Chair had staged a stabbing in a dimly-lit séance, and Davis himself had let the electricity fail in The Haunted House (1924). The blackout-covering-a-killing would be reused in The Spider (1927). The Donovan Affair justifies the device through the luminous ring. In plot terms, it’s another red herring, but it plausibly motivates darkening the stage during the murders. The effect seems to have come off.

The audience found itself frequently strung almost to the endurance limit, and now and then a voice from the crowd would beg a relentless actor not to turn out those lights again. For it was generally in the darkness that stabbings, shootings and assorted mayhem would stalk through the play.

It must have been riveting to see the ring (a green-tinted flashlight) floating around the darkness. Capra’s film is at pains to reproduce this signature effect, but with some differences.

The screenplay subtracts some of the characters and adds a sinister caretaker and Porter, a gambler to whom Donovan owes money. The plot begins well before the crime, with an opening that establishes Porter among his cronies. A second scene shows Donovan brushing off Mary, the Rankin family maid; in the play their liaison is revealed very late. Then guests gather for the birthday dinner, and after some salon byplay they sit down to eat, with Donovan demonstrating the power of the cat’s-eye ring. In the darkness he’s murdered.

A title, “One hour later,” introduces the main stretch of the film, which corresponds more closely with the play’s action. Inspector Killian arrives and sizes up the suspects. Most of the play’s clues emerge, with suspicion scattered around freely.

Like the play, the film is built around blackouts showing off the wandering ring, but now these are motivated as reenactments of the crime. Killian puts Porter in Donovan’s seat, and in the darkness he becomes the second victim. After more intrigue, Killian demands another go-round, and this time the killer is exposed.

The film’s blackout scenes run 36 seconds, 42 seconds, and about 100 seconds for the climax. This last scene varies the treatment by showing some silhouettes.

These scenes feel surprisingly protracted: 30 seconds is a long time on the screen. Likely there would have been dialogue and sound effects, as there are in the play’s blackout intervals.

Here’s the paragraph with the spoiler. In both play and film, the butler Nelson is revealed as the murderer. (At this point in history, having hired help commit the crime wasn’t yet out of bounds.) Nelson is in love with Mary, whom Donovan has seduced. The film hints at this in a way that the play doesn’t. Mary is introduced early as Donovan’s mistress, Nelson seems to have eyes for her, and during a test to see if any woman’s handwriting matches that on a telltale letter, he lingers solicitously over Mary.

Variety praised Capra’s film as well-constructed and surprisingly funny, chiefly because of a whimsical old couple added to the ensemble. Capra claims that The Donovan Affair taught him to add doses of comedy as much as possible: “Comedy in all things.” Actually, though, Owen Davis claimed that he was teasing the genre in his original. “The Donovan Affair was, naturally, a success, although I am, I think, the only one who knows that it was as deliberate a burlesque as The Haunted House had been.”

Opening up the proscenium

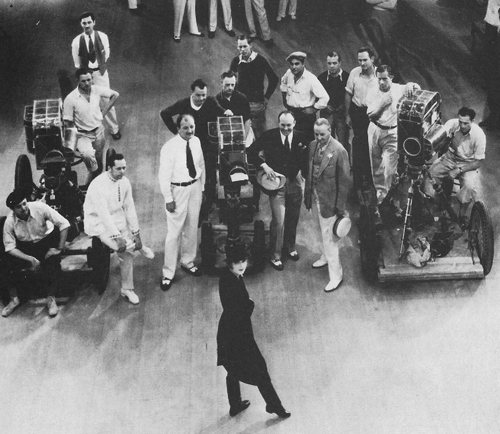

A posed shot of the multiple-camera teams for Sunny (1930).

In his autobiography Capra regarded The Donovan Affair as a turning point in his career. While complaining about the constraints on sound cameras, he regarded the film as “the beginning of a true understanding of the skills of my craft: how to make the mechanics—lighting, microphone, camera—serve and be subject to the actors.” To my way of thinking, what he did within the confines of early talkies was inject some of the pictorial fluidity and impact on display in the silent cinema. The Donovan Affair is a lot less pictorially stilted than most of the 1929 American films I’ve seen.

Like many early talkies, the film relies heavily on multiple-camera shooting of the sort still used in TV comedies and soap operas. For this film, according to Joseph McBride, five cameras were used. The range of coverage allowed for continuous sound recording while preserving the option of analytical editing. While one camera recorded a wide framing, a long lens could scoop out a closer view without moving that camera into the space.

So when Mary calls on Donovan in the second scene, we can see her arrive in a long-lens mid-shot, then we can see Donovan’s reaction in a long shot. Mary comes forward and a third camera picks them up in a two-shot.

The technique permits smooth matches on action, as when Mary turns her head in a medium shot and leaves in the background of the master shot.

But it’s also clear that multiple-camera shooting allowed for alternative takes. The mismatches we can detect across some cuts suggest this. During continuous dialogue, Lydia’s arm is up in one shot and down in the next.

Capra claims that Columbia allowed him to print only one take, but he got around this by not slating his shots. He simply let the camera run and replayed the action, sometimes several times. This allowed actors to improve their performances in a fluid process. CApra wound up with only one take number, out of which he could pick the take he wanted. This tactic might explain disparities of figure position.

Multiple-camera shooting could yield some awkwardness, especially when shot scale wasn’t adjusted. Here’s an interesting example showing Jean’s quarrel with her stepmother Lydia. As Lydia crosses in front of Jean, the match cut on my second frame below creates a little bump by not sufficiently changing the angle and figure size. The slight pan following the women accentuates the disparity.

A jerky cut like this would be very rare later in the 1930s, as it is today. As recording technology improved, Hollywood would move back to single-camera shooting for most scenes, and shot scales were more exactly planned and executed.

If multiple-camera shooting feels a bit theatrical, it’s because it surrenders a degree of freedom in camera placement. We always seem to be watching things from outside a proscenium, even when items are enlarged. I think that the early talkies’ habit of starting with a flamboyant camera movement, as in Sunny Side Up (1929) and The Broadway Melody (1929), was a way of saying, “Don’t worry, this is still cinema.” Capra follows this habit by beginning on a close view of a pile of Donovan’s IOUs and then tracking back very far to set his first scene among the gamblers.

The film’s second “act” starts with a comparable flourish. A long shot of the library shows Carney bustling toward the offscreen front door in the background. The camera tracks in and waits for him to return.

Presumably we would be hearing him greeting Inspector Killian offscreen, but the frame is empty for about fifteen seconds. Then Carney and Killian stride in, and the camera pulls back to something like the initial master framing.

Another way to add fluidity was to insert shots that don’t require lip synchronization. Cutaways to objects or reaction shots could be inserted into the dialogue-laden stretches. For example, Nelson and Mary peer into the library to watch the guests, and Ted Tetzlaff’s cameras give us two shots from positions different than we’ve seen so far.

More boldly, after Donovan is killed, Capra gives us not only a shot of Mrs. Lindsey wailing but brief close-ups of Jean’s and Lydia’s reactions.

These two shots are only 32 and 36 frames respectively, harking back to the punchy montage of silent cinema, and they stand out by contrast with the extreme long-shots around them.

Similarly, you have to think of all those subjective POV shots in 1920s silent films when we watch Killian survey the suspects. As he talks with Rankin, he scans them right to left in a series of POV shots, including one longish, zigzag pan. Here are some extracts.

The end of the pan shot shows Lydia shifting her gaze from Killian to her husband, off left. We then cut to her husband and Killian, who’s just finishing his scanning of the suspects. Her gesture cast suspicion on her; after all, she’s hiding her affair with the dead man.

Most ambitious of all is Capra’s handling of the dinner table situation. Smoothly integrating singles and two shots of characters around a table was one of the triumphs of classical Hollywood style in the late 1910s. Matching character positions and eyelines from shot to shot became part of every director’s craft. Capra adapts talking pictures to these constraints in a flow of shots that include dialogue and keep all characters’ relationships clear and consistent while picking out important details and reactions.

For example, when Donovan talks with Mrs. Lindsey, we get her husband’s glare as he watches from across the table.

Here the proscenium is broken. Instead of covering the action from outside, now the camera penetrates space and can take up a variety of angles among the characters.

This camera ubiquity can be exploited to dramatize the murder weapon. A master shot shows the dinner party, with Rankin at the head of the table and his wife Lydia at the foot, turned from us.

Mary brings the roast and the carving knife to the table. Cut in to Mary lifting the knife, which glints.

Donovan flinches as the reflection dazzles him. Cut to Lydia, from the foot of the table, saying, “Mary,” and looking down the table to where Mary would be.

We’re in a sort of triangular space—Mary-Donovan-Lydia—and the relationships are reaffirmed when a return to the earlier setup shows Mary responding to Lydia’s look.

The dialogue continues within these shots. Capra’s changing setups must have required quite a bit of effort in 1929, what with cameras in booths and the pressures to stick with continuous multi-camera takes. But, reviving silent-film table coverage, he gives us what would be one conventional way to handle such an action in the 1930s.

There are other felicities in the film, but I think I’ve said enough to indicate how it’s an enlightening transitional work. Tied to the multi-camera technique for most of its running time, Capra breaks away for significant stretches. He found a way to give camerawork and cutting some moments of the sort of fluidity that would pervade Hollywood in the 1930s.

Capra wasn’t the only major director to cut his talkie teeth on adaptations of stage thrillers. Hawks made The Criminal Code (1931) from a 1929 prison drama, while Hitchcock based Blackmail (1929) and Number Seventeen (1932) on popular plays from 1928 and 1925. Film mysteries would change in the 1930s, with sophisticated detective comedies like The Thin Man and adaptations of the adventures of Charlie Chan and Perry Mason.

Creaky though it might seem in later decades, the manor-house murder would remain a reference point. On stage its premises were given a new twist in Christie’s The Mousetrap (1952), enhanced with social criticism in J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls (1945), and parodied in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1962). You can argue that the provincial procedurals with a British accent (Wexford, Midsomer Murders, Inspector Morse, and so on) grow out of the spillikins-in-the-parlor tradition, but shifting the viewpoint to that of the detectives.

Thanks to Lynanne Schweighofer, Zoran Sinobad, and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress and Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach of our Cinematheque for arranging my viewing of The Donovan Affair. Thanks also to Ben Brewster for discussions of the film and 1920s theatrical practice.

A fleshed-out synopsis of the film was published at the time.

Bruce Goldstein had the excellent idea of adding live performers to screenings of The Donovan Affair. He details his efforts to find the original dialogue in this TCM article.

Ray Collins fans may be interested to know that in the stage version he played the butler–described in the script as “really the only acting part in the play.”

My quotation about rapt audiences for the stage version comes from the review, “’The Donovan Affair’ Thrills in Mystery,” The New York Times (31 August 1926), 15. Quotations from Capra are from the first edition of his autobiography, The Name above the Title (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 105. Joseph McBride has written the most comprehensive and probing biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

In his autobiography Owen Davis remarks that the failure of The Haunted House, a “burlesque mystery melodrama” impelled him to write The Donovan Affair. That was a play that “could hardly be accused of not being mysterious enough, and one that actually dripped with blood and missed no trick at all of the tried and true tricks of mystery story writing from Gaboriau through Poe and Doyle and Anna Katherine Green and Mrs. Rinehart, even taking in the tricks of the present, and very skillful, crop of hard-boiled detective story writers who were at that time printing their first compositions on a slate in some primary school.” See My First Fifty Years in the Theatre (Boston: Baker, 1950), 94-95.

My exploration of theatrical thrillers has been aided by Amnon Kabatchnik’s two excellent reference books: Blood on the Stage: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire, 1900-1925 (Scarecrow, 2008) and Blood on the Stage, 1925-1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire (Scarecrow, 2010).

As ever in such matters, Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website offers background information and critical discussion of authors, periods, and conventions.

On multiple-camera shooting in early sound film, see Chapter 23 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. A good primary source is Karl Struss’s article “Photographing with Multiple Cameras,” TSMPE XIII, 38 (1929), 477-478.

The Donovan Affair (1929).

Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

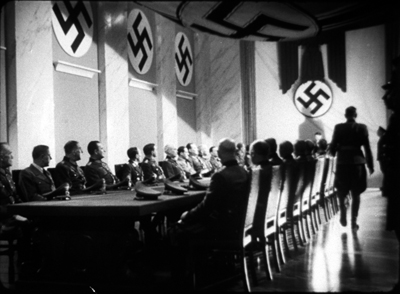

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

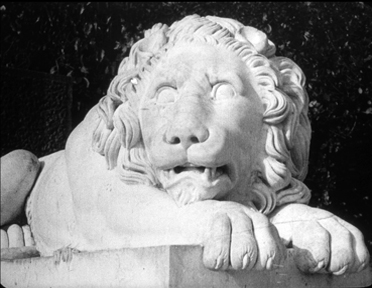

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.