Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.

My girl Friday, and his, and yours

DB here:

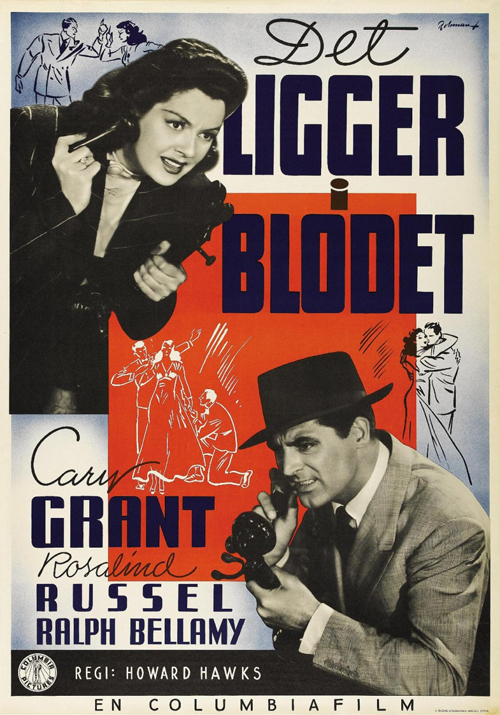

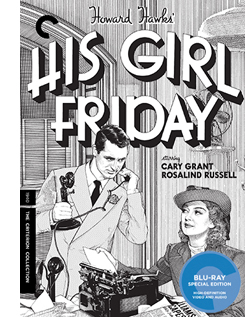

Criterion has just released a fine edition showcasing two classics of American cinema: The Front Page (1930) and His Girl Friday (1940). His Girl Friday is in a new HD restoration, and the earlier film, long crawling around in disgraceful public-domain bootlegs, now has a 4K glow–maybe looking better than it did at the time. The extra fillip is that it’s a version that director Lewis Milestone preferred to the familiar one.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Needless to say, I’d be plugging this release strenuously even if I weren’t involved. Long-time readers of this blog know that an early entry hereabouts talked about the diverse paths HGF took to becoming the classic it’s now recognized to be. I used the film in many courses I taught during my early days at Madison. Kristin and I have been writing about the film since then as well, first in Film Art (it still retains its place from the 1979 edition), then in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1998). Other references sneak into our entries here from time to time. The Criterion edition offered me another chance to rattle on about a movie I still, after nearly fifty years, love inordinately.

What can be left to say? Plenty, but today I’ll mention just two items. First, what is a Girl Friday? And second, how unobtrusively delicate can film style be?

More slop on the hanging

The phrase “girl Friday” comes, ultimately, from Robinson Crusoe, Defoe’s 1719 novel of how the castaway protagonist turned a cannibal prisoner into his servant: his man, Friday. The hapless convert to Christianity gained his name because Crusoe rescued him on a Friday. An 1867 children’s story, “Will Crusoe and His Girl Friday,” shows a little boy and girl planning to reenact Defoe’s tale, adding gender insult to racial and class injury.

“My Girl Friday” was a spicy 1929 play about flappers who drug tycoons at a party and then convince them that the worst has happened. Consisting largely of scenes with chorus girls in bathing suits, it was dubbed by Variety “out and out smut.” Unsurprisingly, it found success on Broadway. During some weeks its BO take rivaled that of The Front Page, on stage at the same time.

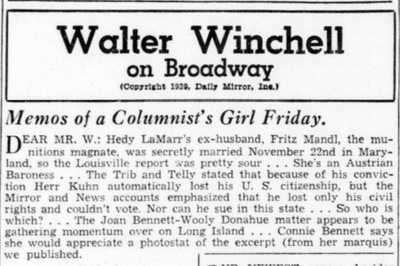

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

He started a brief feud when he smelled poaching. In 1937, two aspiring screenwriters sold MGM a story they called “My Girl Friday.” It involved, according to Daily Variety, “adventures of a newspaper circulation rustler.”

With Trumpian self-regard, Winchell asserted that he had popularized many catchphrases that Hollywood had bought as titles: “Blessed Event,” “Orchids to You,” “Is My Face Red?” “Okay, America,” and even “Whoopee.” In addition, he noted that MGM had spent a cool quarter of a million dollars to enhance a scene of The Great Ziegfeld. In the face of such largesse, Winchell felt justified in asking for compensation.

Therefore we think it would be ducky if MGM sent $10,000 to us for the use of “My Girl Friday,” which became better known via this dep’t.

Winchell hastened to add that he would give the money to charity. He pressed his case in several columns and in radio broadcasts. Paramount joined the fray, claiming that it acquired the title when it bought the old play, so MGM couldn’t use it anyway. At which point the Hays Office was consulted.

Using his Girl Friday voice, Winchell responded that he claimed only to have popularized the phrase, and in any case what was $10,000 to Hollywood, especially if the money went to charity? Muttering about how MGM’s song “Your Broadway and Mine” swiped the original title of his column, Winchell subsided, as did the dispute. MGM evidently never adapted the story in question.

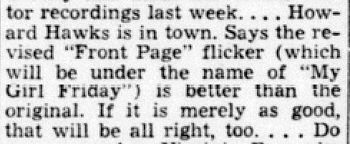

Then, on 9 December 1939, Walter ran this.

No hard feelings from Winchell, apparently. He may have benefited from the association with the movie. During production and even after release, the film was sometimes called My Girl Friday. And the linkage of a Girl Friday to the newspaper game, be it gossip or circulation rustling, fitted the movie well, as it evoked Winchell’s rat-a-tat radio delivery and his near-prosthetic adhesion to phone receivers.

Yet Winchell mysteriously dropped the “Memos” rubric from his column in 1941. In the decades to come, many businessmen would claim to have a Girl Friday of their own. Maybe the film ultimately popularized the phrase more successfully than Winchell did.

For the waiter

Daily Variety (5 January 1940), 3.

As a theatrical adaptation, His Girl Friday offers a challenge that Hawks accepted with ease. He had worked on films limited to a few interiors before, as with the train scenes of Twentieth Century (1934) and much of the airport action of Only Angels Have Wings (1939). He knew how to enliven situations unfolding in tightly confined settings.

Apart from enjoying the fast-paced comedy, you can learn a lot about film technique from the way Hawks energizes his static, prosaic surroundings. Take his resolutely unflashy staging in depth. It’s most apparent in the pressroom of the Criminal Courts Building, as I suggest in the supplement, but there are plenty of felicities of staging elsewhere. The most apparently unpromising example involves the restaurant where Walter Burns takes his ex-wife Hildy Johnson and her fiancé Bruce Baldwin. What to do with this simple set?

At a late point in the scene Walter will seek the help of the waiter Gus, who’ll call Walter to the phone. It’s a basic problem: How should the director prepare for that phase of the action? Hawks does it by setting up a zone of depth at the start of the scene, priming it quietly throughout, and paying it off when it’s needed.

Bruce, Walter, and Hildy enter the restaurant from the background. (Novice directors please note: No need for a sign saying, “Restaurant.”) The group comes to a table in the foreground. After some comic byplay as Walter grabs the chair next to Hildy, the three get seated and chat with Gus.

This framing orients us to the table and the rear area by the bar. We’ll never leave this general orientation on the scene. This commitment, far from being simply “theatrical,” makes for economy as the action develops.

In the course of the scene, Hawks activates the rear zone by having Gus come and go from it. Of course that area isn’t emphasized. Who’s likely to notice Gus giving the sandwich order back there when there’s patter and funny business to watch right in front of us?

In the course of the scene, Gus will come back to the table, pouring water, delivering sandwiches, and getting kicked in the shin by Hildy, who’s aiming at Walter. Throughout, we’re quietly primed for that alley of space behind Walter to be occupied by Gus.

The priming pays off when Walter, realizing that he has to prevent Hildy’s taking the train today, deliberately spills water in his lap.

Walter pivots and heads to Gus, who’s back there in his domain, waiting to be pulled into the plot. He’ll summon Walter to the fake phone call.

No big deal–certainly not as eye-catching as the dazzling comedy around the table. But the care for such little things is the mark of a craftsmanship that uses space compactly, without fuss. No need for camera angles that show the fourth wall (or even walls two and three). No need to build more of the set on the side; this is Columbia, after all. Just let reliable Joe Walker light that background enough to keep us aware of it (out of focus for most of the scene) and then activate it when you need it.

Hawks was obeying the advice Alexander MacKendrick would later give:

Within the same frame, the director can organize the action so that preparation for what will happen next is seen in the background of what is happening now.

Or as Hawks put it in 1976:

You know which way the men are going to come in, and then you experiment and see where you’re going to have Wayne sitting at a table, and then you see where the girl sits, and then in a few minutes you’ve got it all worked out, and it’s perfectly simple, as far as I am concerned.

The unstated premise is indeed perfectly simple: You don’t need to show more space than the physical action requires. It’s a rare premise today.

How long is it?

This sort of priming fits neatly into a cinema based in continuity–dramatic, spatial, temporal. Hawks is a master of staging action so that it flows unobtrusively. At times, though, it’s fun to spot some discontinuities, and editing is a good place to look.

Ozu is, to my knowledge, the only director who invariably creates perfect match-cuts on action. Even Hawks has to cheat things a bit to make the editing flow. (Hildy’s pitching of her purse is an example I use in the commentary.) But consider how Hawks can get a spark out of a small, mismatched action.

We’re still in the restaurant, and Walter has persuaded Hildy to cover the Earl Williams story in exchange for buying an insurance policy from Bruce. Talking of his upcoming physical, Walter boasts, “Say, I’m as good as I ever was.” Hildy fires back, “That was never anything to brag about,” and Walter reacts and turns his head. As he turns, we get these two shots.

At first Walter is stunned, apparently readying a reply; but at the cut, he’s sporting a grin. It’s partly a grin of triumph, showing that he’s gotten Hildy to do his bidding, but it’s also an appreciation of her wit: a sort of “That’s my girl” pride in her fast comeback. Strictly speaking, the cut’s a mismatch, but the instantaneous switch in reaction gives the scene double value.

Finally, there’s framing. The rugged outdoor guy Hawks is as delicate as they come when it’s a matter of frame corners and edges, and his sense of pictorial balance is fastidious. Go back to the long opening scene in Walter’s office, when he and Hildy are going through the preliminaries. They size each other up before Walter sits down in his swivel chair.

A slight track forward has planted Walter in the lower corner of the frame. A cut in to Hildy’s reaction (not shown) enables a transition to a slightly different framing. That setup allows Walter to invite her onto his knee, which pokes up from the bottom edge.

Joe Walker has obligingly edge-lit that stretch of pant leg, and it’s about the only thing moving in the shot, so we can’t miss Walter’s come-on.

Now Hawks does something very pretty. Hildy moves to the table and perches on it. Hawks reframes with her, but keeps the shot oddly unbalanced, with Walter resolutely facing the area she’s not in.

A sort of spatial suspense develops. Hawks sustains this odd framing while Walter picks up a cigarette, tosses one to Hildy, lights up, and tosses her a match. Fairly deliberately too, in what’s supposed to be Hollywood’s fastest movie.

When both are smoking comfortably, Walter swivels his chair to snap his head into the lower left corner, which has been waiting for him all along. The simple movement provides the scene’s new beat, which starts with Walter’s line: “How long is it?” I haven’t yet mentioned that this is a fairly dirty movie, but you knew that.

The shot began with the actor’s head in the lower right, developed with that head poised midway in the frame, and now ends with the head cocked in the lower left. What looks like sterile geometry feels, on the screen, perfectly unforced. And lest we misread the “How long is it?” Walter innocently explains, in a medium shot, that he’s just wondering how long it’s been since they’ve seen each other. That in turn calls up an over-the-shoulder reverse angle, and the next phase of the scene is off and running.

At this point in film history, the cinematographer, while shooting, could not see exactly what the lens was taking in. The careful unbalancing and rebalancing of the shot had to be achieved through a mixture of expertise and intuition. The same thing with keeping Gus in reserve back there by the bar, and letting an incompatible take of Grant’s reaction stay in after a cut. It’s all perfectly simple, as far as I’m concerned.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker of Criterion for inviting me to spend more time with this splendid movie. Hawks’ quotation about keeping it simple comes from my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), 149.

You can find background here on the restoration of The Front Page, supplied by Academy archivists Mike Pogorzelski and Heather Linville.

You can get a sampling of Winchell’s radio delivery from the period here, complete with nervous teletype clackings serving as transitions. For more background on HGF, go here. That entry observes the usefulness of the film’s lines in many situations. In this respect it resembles another Hawks film, that repository of worldly wisdom known as Rio Bravo.

Gus the waiter is played by the inimitable Irving Bacon, one of a dozen or so outstanding supporting players. This is another of the film’s triumphs: Regis Toomey, Porter Hall, Gene Lockhart, Abner Biberman, Roscoe Karns, and other memorable character actors all seem to be having fun. And Billy Gilbert as the wayward Pettibone is the friendliest deus ex machina in Hollywood cinema.

Finally, do audiences today know the meaning of Hildy’s flipped hand in response to one of Walter’s catty remarks? Has nose-thumbing gone out of popular culture? Apparently not.

P.S. 4 February 2017: On the Parallax View site, Sean Axmaker has the most in-depth appreciation of this edition of The Front Page I’ve seen online. And he has plenty to say about HGF too.

P.S. 2 February 2018: His Girl Friday is now streaming on FilmStruck, and among the bonus materials is the video essay I mention.

His Girl Friday (1940).

Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Our contributions to FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel continue. Last month brought Jeff Smith’s analysis of musical motifs in Foreign Correspondent and his celebration of the skill of Alfred Newman, supplemented by a blog entry here. This month it’s my turn, taking on Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata (1943; all Japanese names hereafter in Western order, family name last). My presentation is here, if you are a FilmStruck subscriber. A bit of it is available to all at the Criterion site. Today’s entry fleshes that out with some contextual background.

If the streaming version of Observations on Film Art is a bit like a bonus material on a DVD, think of these blog entries as liner notes with clips. This format allows us to tackle the films from an angle not covered in our videos. We’re sorry that not all of our readers can access the Criterion Channel. But if these entries inspire you to go back to the films in whatever form you can find them, that would be all to the good.

Conquering the self

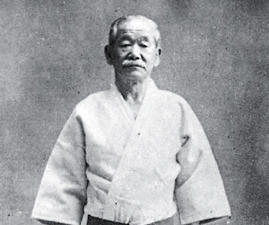

Sanshiro is a film à clef, using martial arts to promote a nationalistic cultural pride. The character of Sanshiro was based on Shiro Saigo (above), who was one of the first pupils of the founder of judo, Jigoro Kano. (In the film, Kano is called Yano, below.) Kano learned the traditional fighting technique called jujutsu (aka jujitsu). Like jujutsu, judo involves grappling, locking, and throwing, and it deploys the opponent’s force against him (or her). But Kano tried to refine the art, eliminating some of the harsher techniques, like biting and kicking, and aiming for maximum efficiency of energy.

By treating judo as a sport and encouraging sparring and public matches, Kano led judo to prominence. His pupils defeated jujutsu challengers. In 1885-1886 matches against Tokyo police champions, Kato’s star pupil Saigo proved judo’s prowess.

In the hands of Kano and Saigo, unarmed fighting techniques were turned to spiritual ends. Ju-jutsu, “flexible technique” was replaced by ju-do, “the path of flexibility”—a devotion to a way of life rather than mere mastery of grips and throws. This distinction is enacted in the film, when Sanshiro, having learned enough technique to bully people with abandon, must learn to master himself.

Judo’s emphasis on spiritual seeking fitted an ideology that emerged in the Meiji period (1868—1912). Japan’s elite was bent on incorporating Western technology and social institutions while maintaining, or rather constructing, a distinct national identity. Accordingly, jujutsu, whose origin lay in Chinese boxing, came into disfavor as part of “feudal” traditions. With young people becoming entranced by Western sports like boxing and wrestling, the government encouraged the development of judo as both modern and uniquely Japanese. As often happened, these “inherently Japanese” cultural forms were of recent invention.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

There’s another dimension to the story. John Dower has pointed out that imperial wartime propaganda tended to emphasize not triumph over the enemy but the need to purify the self. Accordingly, judo’s victory in the social sphere parallels Sanshiro’s conquest of his anger and egotism.

In the film, Sanshiro comes to Tokyo in 1882, the year Kano actually founded his school. After training, both physical and spiritual, the young man proceeds to defeat the surly jujutsu master Monma. Bristling with youth and vigor, Sanshiro then comes to represent a rising generation capable of surpassing its elders. The next fight references Saigo’s most famous combat during the 1886 police tournament. He must defeat the kindly jujitsu master Murai. But he is attracted to Murai’s daughter Sayo, and so it pains him to trounce her father. But Murai acknowledges judo’s superiority and easily forgives Sanshiro. Judo, he says, awakens his senses.

Most intently, Sanshiro’s purity of spirit clashes with the foppish, Europeanized Higaki, who exploits judo for aggression and self-aggrandizement. Their big fight comes on a wind-swept hillside, perhaps a reference to Saigo’s signature technique yama-arashi (“mountain storm”). The polarity Japanese/ Western would become even stronger in the film’s sequel, Sanshiro Sugata II (1945), in which Sanshiro must fight an American boxer. But from fight to fight, Sanshiro gains greater and greater self-possession, so that in the climactic combat, he can spare time to stare at clouds and envision lotus blossoms.

The film’s plot reverses Saigo’s actual life course: He became a street brawler after he won his tournament victories. More basically, Sanshiro Sugata goes beyond its historical sources and political program, as ambitious films tend to do. Nationalistic messages appropriate to wartime are transformed, reworked—”cinematized”—through Kurosawa’s remarkably dynamic approach to film style.

A resumé film?

Sanshiro is a young man’s first film. Kurosawa started on it when he was thirty-two (within my magic-number deadline). In the Criterion Channel video, I treat the movie as an occasion for an ambitious director to display his versatility—a sort of resumé film, as we’d say nowadays, and maybe a little showoffish.

He was ready for the project. He had a busy several years as an assistant director and screenwriter at the fast-moving Toho studios. He worked on twenty-eight dramas and comedies between 1936 and 1942. When he read Sanshiro’s source novel upon publication, he urged Toho to buy it, and he plunged into his project with fervor.

Like other young directors in Japan, he was well aware of developments abroad. His autobiography records seeing many imported films, from Broken Blossoms (1919) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Metropolis (1927) and The Blue Angel (1930). Interestingly, he claims to have seen Storm over Asia (1928), Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher (1928), Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), and even films by Buñuel and Man Ray. His viewing included Hollywood fare by Ford, Lubitsch, Borzage, Wellman, Sternberg, and others. Indeed, he could have kept up with American cinema right up to Pearl Harbor; prints of Edison the Man (1940), Morocco (1930), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) seem to have been playing in Tokyo in late 1941. Then all American films were banned.

So he was a cinephile director, perhaps not quite as passionate as Ozu, but a young man who looked and learned. Like most Japanese directors, he had mastered Hollywood continuity staging and cutting. I’ve argued elsewhere that many of his contemporaries were bolder stylists than the Americans. Whether it’s a matter of long takes, camera movements, rapid cutting, or subtle transitions—the Japanese found their own striking innovations.

Ozu’s distinctive 360-degree staging space, low camera height, and play with graphic editing constitute an extreme example of Japanese pictorial invention, but he wasn’t alone. Take this passage from Naruse’s Street without End (1934). The heroine has left her husband’s hospital bed after denouncing him, his mother, and his sister for selfishness. Servants and family rush past her; he may be dying. She hesitates in the corridor. Should she return?

The pattern of cuts and frame entrances accentuates her uncertainty—taking a step, and halting—while the clashing directions in which she moves (right, left, right) have a Soviet-montage flavor. So do the blank frames at the start of every shot, since we have no idea of where we are in the corridor, or where she is, until she thrusts into the frame. And we don’t know whether she chooses to return or not; the geometrical cutting expresses her hesitation.

This geometrical approach to editing is one of the characteristics of Sanshiro I discuss in the video entry. You see it near the start, when alternating single shots of Yano, back to the river, are intercut with slow tracking shots across Monma and his truculent students. To push the pattern further, the tracking shots alternate—first in one direction, then another. Like two rhyming lines in poetry, each of these cinematic couplets brackets one futile attack on Yano after another. Later fight scenes will get more complicated, but display no less rigorous a patterning. And the purpose is always to add to the tension and excitement of the combat.

Another sort of pattern we find in Sanshiro is simpler, but Kurosawa works some nifty variations on it. It’s also somewhat geometrical, but it serves mostly to accentuate a moment of stillness. This is the axial cut, the shot change that moves in or back along the axis of the camera lens. The effect is of sudden enlargement or de-enlargement, a popping out toward the viewer or a sudden withdrawal. Like most directors, Kurosawa uses the axial cut to enlarge something–here, Sayo’s act of praying for her father at a temple.

When the axial cut is justified as a character’s viewpoint, it has the effect of signaling a sharp narrowing of attention. This happens here, when we realize in the voice-off remark (“How beautiful”) and a fourth shot that Yano and Sanshiro have come upon her. That exemplifies an axial cut that moves backward rather than inward.

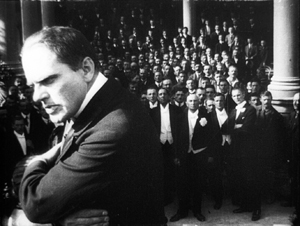

I discussed Kurosawa’s fondness for axial cuts years ago, but it’s interesting to see their origins here. They’re present from the earliest years of cinema, but Kurosawa, again like the Russians, used them expressively. Most uses in Hollywood consist of just two shots, a long shot and then a closer one on the camera axis. But the Soviets, perhaps starting with Eisenstein, multiplied the number of shots and made them fairly brief, so the effect is of a person or object punching out at the viewer. Eisenstein uses the device throughout his silent films, but in both Alexander Nevsky and the two parts of Ivan the Terrible, he develops the device in a very virtuoso manner. Here’s Ivan, standing above the battlefield.

Eisenstein adds to the popout effect by cheating Ivan’s position between shots, so he jumps forward out of his tent.

I’ve found some axial cuts in Japanese films before Kurosawa started directing. One of the most “Kurosawa-ish” comes in a minor 1939 Nikkatsu swordplay film called Faithful Servant Naosuke (Chuboku Naosuke). Again, the cut-ins emphasize a poised moment.

Even if Kurosawa didn’t invent the technique, he made it more prominent and percussive in Sanshiro. It makes the pauses within combat as staccato as the action of fighting. I spend some time in the video talking about how this all works in particular scenes.

Kurosawa’s next film, The Most Beautiful (1944), itself a real beaut, uses the technique quite differently, mainly for tension. His later films continue to explore its possibilities. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2 (1945) resorts to the device to express our hero’s lingering departure for the big duel. He trots toward us, and each time he pauses to look back, Sayo bows.

Today’s filmmaker would probably pull us back with a tracking or crane shot, but by relying on editing Kurosawa gives us his typical crisp geometrical patterning. The abrupt cuts underscore Sanjuro’s realization that he may not return from this life-or-death confrontation. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2, along with the first film and The Most Beautiful, is available from Criterion, as a disc and on FilmStruck streaming.

My streaming presentation discusses other cinematic strategies Kurosawa employs, but these remarks should give you a sense of just how energetically creative he’s being in his first film. It’s a very flashy item, and it looks far into the future. Decades of kung-fu films have been based on dueling dojos, rival fighting methods, and escalating challenges. In addition, Kurosawa’s technique, moving lightly under the weight of an official message, seems very modern.

Youthful, too. As he told Donald Richie, “I really make my films for people in their twenties.”

The information about the history of judo comes from Gabrielle and Roland Habersetzer, Encyclopédie des arts martiaux d’extrême orient (Amphora, 2000), 265-268, 300-301, 549, and 765. Kurosawa lists films he saw in his youth in Something Like an Autobiography, trans. Audie Bock (Knopf, 1982), 73-74. John Dower’s discussion of Japanese propaganda is in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1987). The closing quotation comes from a 1962 conversation reprinted in Akira Kurosawa Interviews, ed. Bert Cardullo (University of Mississippi Press, 2008), 8. Thanks to Hiroshi Komatsu for information about Faithful Servant Naosuke.

Street without End is available in the Criterion Eclipse collection Silent Naruse. If you don’t have this set, get it pronto.

Informative books about Kurosawa and Sanshiro include Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa third ed. (University of California Press, 1999); Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa, rev. and exp. ed (Princeton University Press, 1991); and Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune (Faber, 2001). Especially revealing about Kurosawa’s production methods in his later films is Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa, trans. Juliet Winters Carpenter (Stone Bridge Press, 2006). On the “spiritist” trend in government policy in the media of the period, see Peter B. High’s magisterial The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), Chapter 6.

For more on axial cutting in Soviet and modern films, and The Simpsons, go here. I discuss Eisenstein’s axial cutting in The Cinema of Eisenstein, Chapters 2, 4, and 6. On Ozu’s characteristic staging, shooting, and editing system, see my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available for download from the University of Michigan Library site. The full PDF takes a while to download, but you can get access quickly by clicking on “List of all pages.” I discuss other aspects of the tradition from which Kurosawa comes in Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 12 and 13. See also the Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Shimizu entries on this site.

Kim Hendrickson, Criterion producer, and Grant Delin, DP, filming DB from a closet.

Murnau before NOSFERATU

Der Gang in die Nacht (The Dark Road, 1921).

DB here:

For many decades, The Last Laugh (Der Letze Mann,1924) was the F. W. Murnau film. If you were a film buff in the fifties or sixties, that staple of film societies and college courses was probably the first Murnau you saw. Eventually you got to those French favorites, Sunrise (1927) and Tabu (1931). Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (19226) came along in there somewhere. Tartuffe (1926), great as it is, has always seemed a specialized taste.

Today, I think, Nosferatu is probably the one everyone sees first. It fits the modern taste for horror movies, and it is genuinely scary. It popped up in music videos, got remade by Herzog, and will be forever remembered for the vampire’s spindly, ratlike silhouette and the wholly fitting name of the performer, Max Schreck.

Eventually Murnau aficionados caught up with lesser-known Burning Soil (Der brennende Acker, 1922), Phantom (1922), and The Finances of the Grand Duke (Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs, 1923), the latter two available on good DVD versions. But what about Murnau’s very earliest films?

Of the nine films he made before Nosferatu, only two survive more or less complete. They circulated in unsatisfactory condition for many years, but Schloss Vogelöd (The Haunted Castle, 1921), which Murnau made just before Nosferatu, eventually emerged in a splendid restoration based on original negative material. Now we have a digital restoration of Murnau’s earliest surviving film, his seventh: Der Gang in die Nacht (The Dark Road, or “Path into Darkness,” 1921).

And what a restoration it is! The Munich Film Museum’s team has created one of the most beautiful editions of a silent film I’ve ever seen. They started with four reels of camera negative, then carefully integrated material from other sources. Thanks to digital manipulation, I couldn’t tell where the alien footage was.

You look at these shots and realize that most versions of silent films are deeply unfaithful to what early audiences saw. Compare a shot from the lamentable YouTube bootleg and a shot from this version. The smallness of the YouTube image here improves it; blow it up on a big monitor and it goes horribly blotchy.

In those days, the camera negative was usually the printing negative, so what was recorded got onto the screen. The new Munich restoration allows you to see everything in the frame, with a marvelous translucence and density of detail. It will project fine big. Forget High Frame Rate: This is hypnotic, immersive cinema.

Der Gang in die Nacht will be shown in the Museum of Modern Art’s “To Save and Protect” series on 13 and 14 November. If you can get there, you should go! If not, we can hope that the film will soon appear on DVD. Remember DVDs?

Silents, golden

The canonized classics of Expressionist cinema, from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari onward, are superb films, no doubt. But there are lots of other major movies from the period. The German industry flourished during World War I, and even the postwar inflation encouraged a burst of moviemaking. Hundreds of films were produced every year. I’m no expert, but of the seventy or so I’ve seen nearly all are fascinating and surprising. From the brute force of Der Tunnel (1915) and the demented monumentality of Homunculus (1916) to the weirdness of Algol and I.N.R.I. (both 1920), the peculiar pleasures of Sappho (1921) and the splendors of The Nibelungen (1924), I’ve been captivated by this cinema. Caligari is merely the dark and spiky tip of a mighty iceberg.

Der Gang in die Nacht is derived from a screenplay by the Danish scenarist Harriet Bloch. It’s an example of the “nobility film,” a genre cultivated by the Nordisk studio where Bloch worked. In these stories, an upper-class man becomes obsessed with a working-class woman, and she leads him to disaster. The most famous “nobility film” of the era is Dreyer’s The President (1919), when the genre was already somewhat old hat.

In Murnau’s film, the well-to-do protagonist is Dr. Eigil Börne. Uneasy with his courtship of his wispy fiancée Helene, he plunges into an affair with the dancer Lily. They move to a seaside cottage, where their idyll is interrupted by the spectral figure of a blind artist. (Regrettably, we never get a glimpse of his paintings.) The Painter is played in nearly full Cesare mode by Conrad Veidt: drifting through the landscape and clutching at the air. After Dr. Börne restores the Painter’s sight, Lily falls in love with him and leaves Börne. Unhappiness ensues for all, and yes, suicide is involved.

With only four delineated characters, the plot’s emphasis falls on their reactions to each others’ changing feelings. It’s a surprisingly unsensational melodrama, with no blackmail, threats of murder, or guilty secrets. It’s just about people’s emotional attachments waning, often for reasons they don’t understand. The drama of shifting, elusive moods looks fairly modern.

The playing is deliberate, with a range of acting styles. The drooping Helene, the skittish Lily, the somnambulistic Painter, and the raging Börne may seem to come in from four different movies. But Börne is on a knife-edge from the start, when he nervously leaves Helene. He broods fiercely during his night at the theatre, well before he succumbs to Lily’s charm. Like Scotty in Vertigo, he’s ready to fall. And as a complacent bourgeois, he doesn’t grasp the romantic fascination projected by the passive, wraithlike Painter. Nor is Lily merely flighty and treacherous. The Painter seems to stir her to a genuine love very different from her flirty seduction of the doctor. Helene, mournful throughout all this, is last seen in her sickbed stroking a newspaper photograph of Börne.

The concentration on four characters, each trembling with uncertainty, and the meshing of their moods with the stormy seaside, suggested to one observer an analogy with current stagecraft.

Here for the first time filmmakers try to incorporate the Kammerspiel [chamber play] into a film play. A strong, affecting plot with only a handful of characters has been developed through the smallest psychological details, the unity of locale and characters, the intimate interweaving of the atmospheric mood and the characters’ emotional life. All this has been achieved with the most sophisticated use of facial expression and cinematic direction.

1921 is usually taken as the year that the Kammerspiel genre began, with Scherben (Shattered) and Hintertreppe (Backstairs). Der Gang in die Nacht, which came out before either of these, isn’t usually considered an example. It’s interesting that the review I quoted, based on a December 1920 press screening, sees Murnau’s film as anticipating the trend. Perhaps the more rigorous concentration of time and space in the later films made critics take them for purer prototypes of the genre.

Knowing this background, I think, makes Der Gang in die Nacht more intriguing than it might at first seem. But another context is important too. The film shows Murnau’s debt to an important stylistic tradition. What he did with it is in sync with other filmmakers learning their craft at the same time. (Some spoilers ahead.)

Tableau + insert = proto-continuity

During the years 1908-1920, many filmmakers relied a “tableau” style of filmmaking. The used long shots and long takes, with the actors shifting in expressive patterns around the setting. The tableau might be broken up with titles or close-ups of letters or diaries, but the drama is developed through action played out in the distant framing.

Early historians, and many still today, portray this approach as merely “theatrical.” In fact, because of the way the camera lens creates a pyramidal playing space (the tip resting on the lens), the tableau approach is very different from proscenium theatre, which has a wide, lateral playing space. The result is a choreography of figure movement in breadth and depth that is no less “cinematic”—that is, specific to the film medium—than editing.

Want clarification? There’s a video lecture here, and more discussion in these entries.

In the course of the 1910s, however, filmmakers started to alter this approach. For one thing, they started to cut up the tableau more. American filmmakers were most radical, often abandoning the long shot altogether and building scenes out of several partial views—medium-shots and close-ups. But most European filmmakers were more conservative. They began to use what researchers have come to call the scene-insert method.

The tableau (the “scene”) would be interrupted by one or two closer views of a face or gesture, before returning to the main framing. Almost always the inserted shot is taken from the same camera position as the long shot. The cut is “axial,” along the lens axis of the camera. It enlarges a slice of space given in the wider view, then usually cuts back along the axis to reestablish the tableau.

Here’s a simple example from Joe May’s delightful serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919-1920), when a nurse in the room in the background rises.

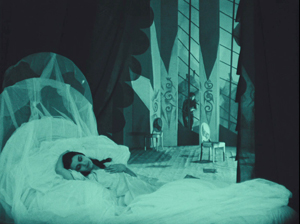

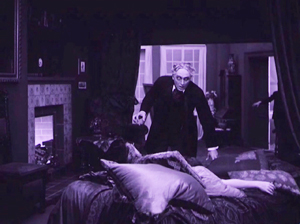

The axial approach is used throughout Caligari too. When Cesare invades Jane’s bedroom, we cut straight in and then cut back as he approaches.

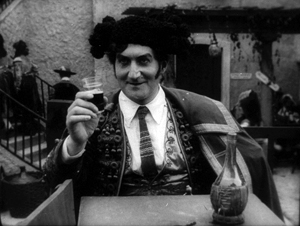

In Kristin’s book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available as a pdf) she traces several instances in other German films, as in this passage from Carmen (1919), with Don José way back at the rear of the tavern–but still on the lens axis.

Der Gang follows the scene-insert method often. The only closer view during Lily’s tea flirtation with Börne emphasizes her teasing gesture and his reaction.

The result is a minimal version of analytical editing, a sort of rough, proto-continuity approach to breaking up a scene into details. It can be thought of as a transitional phase toward a fully “classical” style of staging and cutting, and indeed in the 1920s more and more European filmmakers adopt versions of the Hollywood method.

Already, we can see some filmmakers thinking in terms of an establishing shot rather than a tableau. Murnau’s long shot below is probably too far distant to permit a complex play of depth of the sort we see in Caligari and Carmen. It’s designed, we might say, to be cut into.

During this transitional period, we find films exploring the scene-insert method in intriguing ways. The most evident is the tendency to make the cut-in shot very close.

In Paul Leni’s Dr. Hart’s Diary (Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart, 1918), for instance, we get a rather distant shot showing the wounded Count Bronislaw carried out of the ambulance, followed by a very tight medium-close-up of him and Jadwiga, the Red Cross nurse.

An American director would have been more likely to soften this sudden enlargement with a mid-range two-shot of the couple before providing the intense close-up of their faces.

This abrupt jump into a surprisingly close view isn’t uncommon in European cinema of the period, and it’s particularly salient in German films. The insert is often taken with a wide-angle lens, which can accentuate the curves and edges of a face. Murnau’s fondness for the wide-angle lens is a constant throughout his career. A fragment from his first, lost film The Blue Boy shows a wide-angle depth composition, and there’s an astonishing wide-angle close-up of the distraught painter in Der Gang.

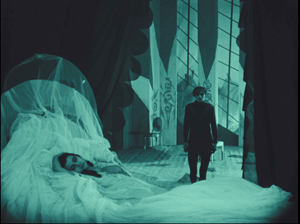

Like many directors working in this line, Murnau balances the power of the sustained long shot with the momentary spike of the closer view. A good example comes in the beautiful passage when Börne discovers that Lily is dead. The setup is given in a classic tableau framing, with only her arm extending out from cushions on the divan. Then the Painter’s head lifts into center frame from behind the pillows, a slow revelation of his pain.

After alternating cuts to Börne hammering at the door, the Painter rises and floats to the door in the back wall. (The rear door is a fixture of the tableau tradition, as it allows for dynamic movement in depth within the visual pyramid.) Once the doctor is admitted, he rushes forward and pauses as the Painter glides into the background.

As Börne wails, Murnau pushes us into the parlor to the Painter, standing in the distant corner like an upright corpse—an alternative version of grief.

Like many films of the period, not only German but also French and Italian ones, Der Gang in die Nacht exploits the resources of the tableau—the graceful, expressive coordination of actors who perform with their whole bodies—while saving the blunt force of the isolated face for a climactic accent. No wonder that film theorists of the late ‘teens and early 1920s were fascinated by close-ups; they were seeing a great many vivid ones.

Not haunted, just mysterious

There were a lot of variants on these techniques. As if to give us the tableau and the wide-angle insert in a single frame, Robert Reinert cultivated a looming deep-focus style that suggests a Citizen Kane of the 1910s. The first frame is from Opium, the last two from Nerven (both 1919).

And the extraordinary Weisse Pfau (The White Peacock, 1920) of E. A, Dupont comfortably switches from a dizzying gridded tableau (two men arriving at a theatre lobby, caught in an architectural Advent calendar) to a violent climax using highly fragmented editing.

By 1921 the simplest version of the tableau-plus-insert method was rapidly going out of favor. To get a sense of how techniques were changing at the time, you should watch Murnau’s Schloss Vogelöd (1921) immediately after seeing Der Gang in die Nacht.

The plot is a bit friendlier to our pulpy tastes, involving a past murder that is brought to light during a country house party. (No spooks haunt the castle, just the lingering effects of mysterious death.) Again, there’s a chamber-play aspect to it. Virtually all the action is confined to the mansion of the host, von Vogelschrey, and plays out in a couple of days and nights.

Schloss Vogelöd was released only three months after Der Gang in die Nacht. In the sparkling restoration provided by the Murnau Stiftung, Schloss runs almost exactly as long as the earlier film. But what a difference! I count 231 shots in Der Gang, with 163 of those being images, not titles. I count 511 shots in Schloss, with 356 of those being images. Assuming a common projection speed, the later film is cut over twice as fast.

The sheer number of shots is important, but the crucial factor is that many of the shots in Der Gang retain one particular framing, interrupted by titles or a diary or letter insert. Not only does Schloss have more shots, it has more varied setups. Murnau is shifting his camera positions more often, as were his peers Lang and Dupont, along with other Europeans and of course the Americans.

Here’s an example. At a meal, the vengeful Count Oetsch hints that Baron Safferstädt is the murderer. The scene runs about three minutes and contains 16 shots and five titles, played out across six distinct setups. I sample them here.

In a loose sense, the cuts are axial, enlarging or de-enlarging parts of the table as observed from one general orientation. (The judge who stands up and looks left is at the foot of the table.) But within this overall orientation, there’s a variety of setups we don’t find in Der Gang. We aren’t far from that spatial ubiquity and adherence to an axis of action that was pioneered in 1910s Hollywood and would become increasingly common in Europe during the 1920s. The downside: The development of more finely broken-down scenes led to a loss of the complex choreography within a single shot that was common in the early 1910s.

Der Gang in die Nacht was filmed in August-September of 1920; Schloss Vogelöd was shot in February and March of 1921. In between Murnau made Marizza, genannt die Schmuggler Madonna (Marizza, called the Smuggler’s Madonna, not shown until 1922). The fragments of this that have survived are very rudimentary filmmaking, much simpler than anything in either of the other two films.

The faster cutting and more varied setups of Schloss may, as Kristin has suggested, owe something to the arrival of American films. Banned until January 1921, they may have inspired German directors to push further toward analytical editing. She has also mentioned in Exporting Entertainment that some American films did slip through the ban and get screened during the war years, so directors could have had an inkling of what Hollywood was up to.

In any event, Der Gang in die Nacht admirably lays out one set of directorial options that emerged as filmmakers of the first “movie generation” (Murnau, Dreyer, Gance, Lang, Dupont et al.) shifted away from the pure tableau style. All became virtuosos of editing, but they never forgot the power of the sustained long take.

Thanks to Stefan Drössler of the Munich Filmmuseum for information on the restored Der Gang in die Nacht. Thanks as well to Sabine Gross for her translation of German material. As ever, I owe an enormous debt to Gabrielle Claes and Nicola Mazzanti of the Cinematek in Brussels.

The review citing Der Gang as a Kammerspielfilm is reprinted in Film-Kurier (30 December 1920), 2. I was led to this by Lotte Eisner’s Murnau (University of California Press, 1964), 92. Although it’s long been out of print, her book remains a very useful source. Also helpful are Los Proverbios chinos de F. W. Murnau, vol. 1, ed. Luciano Berriatúa (Filmoteca Española, 1990) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Ein Melancholiker des Films, ed. Hans Helmut Prinzler (Deutsche Kinemathek, 2003).

Schloss Vogelöd is available on two DVD editions, one from Kino and the other from Masters of Cinema. My frames come from the Kino edition, chiefly because they’re brighter than the higher-contrast MoC edition, and thus more legible on the Net. Both editions have their strong points, as DVDBeaver indicates. Surviving frames of Murnau’s first film are available on the Lost Films website.

Many issues of tableau style and its relation to editing technique are discussed in my On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, and Poetics of Cinema. On this site, among entries on the tableau tradition, the entry most relevant to today’s piece is “Not quite lost shadows.” I discuss Danish approaches to the tableau in the essay “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” and the case of Dreyer’s relation to his peers in “The Dreyer Generation,” on the Danish Film Institute website.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel, The Banks of the Spree Near Stralau (1817).