Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

The book stops here: Theory, practice, and in between

Tinpis Run (Pengau Nengo, 1991).

DB here:

Apart from things I’m reading for research (academic monographs, 1940s Hollywood novels, star bios and autobios), the film books I like best are blends. They bring together information, ideas, and opinion. I learn some facts about films and their contexts. I encounter some concepts that illuminate those facts. And I get introduced to some arguments about the best way to understand the information and ideas. In my ideal world, the blend winds up answering some questions—maybe questions I’ve thought about, maybe ones that never occurred to me.

I especially like books that have one foot, or toe, in filmmaking practice. The poetics of cinema I try to practice is, from one angle, an effort to grasp the principles underlying filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes those choices are announced by the filmmakers; sometimes we have to reconstruct them on the basis of the films and other data. So for me a drastic split between theory and practice isn’t very informative.

These pronunciamientos are but prelude some comments on books that push several of my buttons. Maybe they’ll do the same for you.

Philosophy goes to the multiplex

Stagecoach (1939); True Grit (1969).

What book brings together Cézanne and Tony Soprano, Gregory Peck and Simone de Beauvoir, Plato and South Park, The Twilight Zone and Wittgenstein?

Okay, I know the answer: Practically every book by a littérateur convinced that Great Big Theory gives you a way of talking authoritatively about anything, especially pop culture. So I rephrase my question: What book brings together these and many more items with care, rigor, and infectious amusement?

That narrows the field quite a bit. A strong candidate is a book that has chapters like “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” and “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween”— not the movie but the holiday itself.

The short answer to my question: Noël Carroll’s new collection of essays, Minerva’s Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures.

Noël Carroll isn’t merely the most important philosopher ever to write about popular culture. He has been for decades a major force in film theory and criticism, as well as a philosopher making contributions to moral and legal theory, historiography, and a welter of other areas. His fertile mind and prodigious typing skills have combined to produce over fifteen books and a list of articles running to triple digits.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

This focus on film theory stems from the fact that Noël’s first Ph.D. degree was in film studies. But soon afterward he went on to get a second Ph.D. in the philosophy of art. His cinema research was always philosophically informed, but once he became a card-carrying philosopher, he commuted between two academic areas. He helped found the broader movement called Philosophy of Film, and he continues to write on a lot of different topics. His Humour: A Very Short Introduction is due out in a couple of weeks.

Minerva’s Night Out scans the range of his interests—not only all types of media (which he genuinely enjoys) but a variety of the philosophical puzzles they pose. These he tackles with verve, patient but not plodding analysis, and a range of references that make you wonder if this guy has seen and read pretty much everything.

Here’s the sort of thing that Noël thinks about. We all know that to enjoy a movie fully we often have to appreciate the way in which a star’s performance builds on previous roles. But there’s a problem. The fictional world of a film makes only certain types of knowledge relevant to our experience. At the center of this knowledge is what Carroll calls the “realistic heuristic,” the premise that all other things being equal, the things happening in the fiction are assumed to operate under the laws of our everyday world. Sherlock Holmes (whether incarnated by Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch) is presumed to have lungs like the rest of us, unless we’re told otherwise. Likewise, it is true in the fiction that a room’s walls are solid, while they might in reality be fake. If I see the walls as painted sets or green-screen mattes, then I’m not responding to them as part of the story world.

The same attitude shapes our sense of the unfolding plot. Armed with the realistic heuristic, we have to assume that characters’ destinies are open, that many things can happen to them (as with us). But the principles by which a movie fiction is constructed—say, boy gets girl—aren’t part of our realistic heuristic. “What we believe is probable of a movie qua movie is radically different from what we believe to be probable in a movie conceived as a credible fictional world.” Movie lore tells us that boy will get girl, but to grasp and respond to the story emotionally, we have to feel in doubt. (Perhaps this is what people mean when they say that a mistake in the movie, or a distraction in the auditorium, takes them “out of the movie.” We’ve left the fiction.)

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Carroll comes up with an ingenious explanation. Movies summon up star personas in the manner of allusions. Just as our experience is enhanced when we see a movie refer to another movie—Carroll’s example is a citation of Rocky in In Her Shoes—so do our mind and emotions respond to the presence of the star, as either a continuing allusion throughout the film or a one-off one, as with a cameo or walk-on. As he often does, Noël points out that practicing filmmakers use the concepts he elucidates. “Allusive casting” became part of the 1970s trend of paying homage to old Hollywood, but even in the studio era it wasn’t unknown. Carroll points to The Bigamist (above left), in which somebody says another character looks like Edmund Gwenn. Of course said character is played by Edmund Gwenn.

I’ve shrunk down Carroll’s line of reasoning to give you the flavor of the way he thinks. His piecemeal approach to theory focuses not on loosely named topics but specific questions. For example:

What if anything justifies us talking about popular culture as all one thing?

How do fiction films engage us in the emotional lives of their characters? Hint: It’s not through identification.

What makes us laugh at Mr. Creosote, rather than be horrified or disgusted by his vomit-laced gluttony?

How does a tale of dread, such as Poe’s “The Black Cat,” differ from a horror story?

Why should we care about Tony Soprano, who barehanded commits “crimes of which I don’t even know the names”?

Are the feelings awakened by art akin to friendship?

What role do moral emotions, such as the sense of community, play in our response to characters?

As for the jokes, they’re not of the esoteric academic type but rather straight-out funny. Just one essay, on the vague/implausible (you pick) notion that modernity (traffic, window displays, lotsa flashing lights) changed the very faculty of human perception:

The human eye rarely fixates; saccadic eye movement is the norm. We did not suddenly become attention-switching flâneurs in the late nineteenth century; we have been natural-born flâneurs since way back when.

No amount ot cultural conditioning will succeed in making normal viewers worldwide literally see human faces as cross-sections of centipedes.

I’m sure he’d give any indie filmmaker the rights to make Natural Born Flâneurs.

Viewers and their habits

Natsukawa Shizue in Town of Hope (Ai no machi, 1928).

Carroll tries to figure out certain logical conditions on spectators’ experience in general. That’s one province of film theory. But he’s also sensitive to the constraints on those conditions, the ways that historical and institutional circumstances can shape how viewers watch movies. (That’s part of the star-as-allusion argument.) Other researchers, historians by trade but sensitive to theoretical implications, have tried reconstructing the activities of theatres, trade personnel, and audiences in particular times and places.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A similar approach, but focused with razor acuity on a single country and period, is Hideaki Fujiki’s Making Personas: Transnational Film Stardom in Modern Japan. This book is an expedition into a nearly sunken continent, Japanese film of the silent era. Frustratingly few films have been preserved from those years, but paper documents abound. Fujiki has made intense use of them to answer the question: What were the cultural causes and results of the early star system in Japan?

The answers are rich and detailed. The very first stars weren’t on the screen at all; they were the benshi who narrated the silent program. Hideaki goes on to trace the career of the paradigmatic male star, Onoe Matsunosuke, and to show how his main traits (virtuosity and stature as “great man”) were reinforced by a troupe-based business model. Later chapters focus more on female stars, with emphasis on the influence of American actresses like Clara Bow. The flapper figure shaped not only Japanese female performers but women in real life.

Fujiki traces in some detail how the “modern girl” or moga floating through Ginza owed a good deal to Hollywood movies. He makes good use of what films survive from this period, particularly The Cuckoo (Hototogisu, 1922) and Town of Love (Ai no machi, 1928). In-depth analysis of the star image Natsukawa Shizue, above, allows him to discuss fan culture and movies’ role in accelerating trends in fashion and advertising. In all, Making Personas is a fascinating consideration of stardom as both an industrial and social construction in one of the world’s most important national traditions.

Education and environment

Institutions of another sort feature in two impressive books from the prolific Mette Hjort. She has had the very good idea of assembling documentation about how film schools work. How do different schools, academies, and more informal agencies understand the craft of filmmaking? What ethical values and social commitments are brought to the classroom and enacted in the production process? What are the histories of film schools around the world?

The answers come in two packed anthologies, The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, The Middle East, and the Americas, and The Education of the Filmmaker in Europe, Australia, and Asia. From these we learn of the creative practices put into action by institutions in Nigeria, Palestine, Denmark, the West Indies, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Sweden, Germany, Australia, Japan, and many other localities. We get a real sense of intercultural communication and its breakdowns. Rod Stoneman points out that Tinpis Run, Papua New Guinea’s first indigenous feature, demanded postproduction discussions when outsider viewers couldn’t distinguish the villages presented in the story.

Things happen in these places that would astonish students at UCLA and NYU. Hamid Naficy tells of taking his Qatar students to Tanzania, where they worked on research projects only after spending the morning doing clerical and custodial work in schools and hospitals. We learn of children’s filmmaking initiatives in Mexico City, programs for at-risk youths in Brazil’s City of God favela, and students making photo and sound montages in Calcutta. One purpose of Mette’s collections is to remind us that film training goes far beyond getting your MFA and a showreel on a maxed-out credit card.

Hjort’s initiative, while already stimulating, ought to be continued and enriched. People are starting to understand the importance of film festivals within film culture—as distribution mechanisms, publicity arms, and in a roundabout way feedback systems shaping production. (One essay, by Marijke de Valck, points out the move by festivals toward film training.) More generally, we need to understand film education at all levels as shaping film production and film audiences.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Their first book, Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge argues that apart from films like An Inconvenient Truth, which wear their green politics on their sleeve, there’s a much bigger and broader tradition of films about humans and the environment, ranging from fictional films with explicit messages, like Happy Feet (2006), to films with unintentional ones, like The Fast and the Furious (2001).

As “second-wave” practitioners of eco-criticism, Murray and Heumann aren’t much concerned with cheerleading or finding villains. They want to explore how media representations of the environment have responded to various cultural pressures. Their two most recent books are good examples. That’s All Folks? (2009), building on their analysis of Lumber Jerks in their first book, concentrates on American animated features. They perform careful symptomatic readings while also providing industrial context, such as the tactics by which Lucas and Spielberg adapted to the growing dinosaur craze of the 1990s.

In Gunfight at the Eco-Corral (2012), Murray and Heumann tackle the Westerm on similar grounds, ranging from Shane and Sea of Grass to There Will Be Blood and Rango. Reading these chapters I was reminded how often the genre’s plots hinge on disputes over natural resources. Water, minerals, timber, grazing land, and what the authors call “transcontinental technologies” like the telegraph and the railroad are at the heart of classic Westerns, and the genre’s formulaic conflicts often have strong ecological resonance. This is the sort of criticism that refreshes your vision of movies you think know very well.

Their next book, Film and Everyday Eco-disasters is due out in June.

Things stick together

Lone Survivor (2013).

Finally, two more books merging theory and practice—but from opposite ends of the spectrum. One question that intrigues me involves coherence and cohesion in film. Roughly speaking, coherence involves the way the whole movie hangs together. If it’s a narrative film, how do the scenes or sequences fit into the larger plot? If it’s not narrative, what other principles organize the whole shebang? Cohesion involves how adjacent parts fit together—shot against shot, sequence to sequence. Both these concepts have practical implications, since every filmmaker confronts concrete choices about them in scripting, shooting, and editing.

Michael Wiese has contributed enormously to our understanding of filmmaking practice by publishing a series of books on cinema craft. The most recent one I know is by Jeffrey Michael Bays and it bears directly on cohesion. It’s called Between the Scenes: What Every Film Director, Writer, and Editor Should Know about Scene Transitions. Bays himself has written and directed films, written radio dramas (a great place to study transitions), and published books on filmmaking.

Between the Scenes is an entertaining and damn near exhaustive account of the ways that images and sounds can tie one scene to another. Bays considers aspects of space, like location or objects or actors; time; and visual graphics. The book also shows how sounds can bind scenes or emphasize sharp contrasts. In the example from Lone Survivor above, a soft whir of helicopter blades is heard over the first shot and grows louder when we move from the map to the landing area.

In a web essay called “The Hook” I explored some aspects of this process, but Bays goes into much more detail with many recent examples. He also raises ideas I never considered. For example, if we think of narratives as people traveling from one place to another (and most narratives are that, at least), then every filmmaker faces a choice: Show the journey or don’t show it. And if you show it, what parts and why and what does it tell us about the character? The larger point is: “Make sure you know where every character goes between every scene.” Thinking about this suggests ways to enrich your presentation, and it allows the characters—if only in your imagination—to inhabit a more fleshed-out world. Ideas like this can provoke everyone, filmmakers and film scholars alike.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

This example is simple, but once Chiao-I gets going, she’s able to show how nearly every cut or camera movement can be seen as activating a unique tissue of cohesion devices. The words in a paragraph not only refer to ideas or things; they also link to other words in the paragraph and in the larger discourse. Similarly, in film, different aspects of the images and sounds stand out and adhere to one another instant by instant. Tseng’s analyses of passages in Memento, The Birds, The Third Man, and other films are accompanied by equally close studies of television commercials and educational documentaries. At the end, analysis is supplanted by synthesis, as she shows how the configurations she has pulled apart coalesce into levels that highlight characters and actions. It’s a fresh way to think about how we understand films within genres and stylistic traditions.

In effect, she’s showing the fine-grained patterns that emerge from the choices every filmmaker faces. It would be fascinating to sit in on a dialogue between Bays and Tseng, for they belong to the same community, or so I think anyhow. We’re all trying to understand aspects of cinema, and by focusing on certain phenomena rather closely, we have a good chance to understand them better.

So to the filmmaker who’s skeptical of theory, I say: We can’t think clearly without concepts, or talk clearly without terms. We need to develop rigorous ideas and arguments (i.e., theory) to understand film as best we can. But to the would-be theorist I say: Keep fastened on the look and feel of the films, and test your ideas and arguments not only against them, but against what you can find out about the craft of cinema, in all its historical implications.

I was pleasantly surprised, after I’d decided to talk about these books, to find work by Kristin and myself cited in some of them. Remaining coldly objective, however, I didn’t let these mentions diminish my praise.

Rango (Gore Verbinski, 2011).

Otis Ferguson and the Way of the Camera

The original entry at this URL, published 20 November 2013, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I discuss the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!

GRAVITY, Part 1: Two characters adrift in an experimental film

There was no way to rely on anything we knew before this film. No character was like Stone, no film set was ever like these sets, not one member of this crew had ever done this before. We all were doing something that had never been done before.

Kristin here:

Back in mid-September, on the verge of leaving Madison to attend the Vancouver International Film Festival, I mentioned that I had watched one of the trailers for Gravity and thought it looked like “the most exciting new piece of filmmaking this year.” I added that the trailer “called ‘Drifting’ reminded me of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative, with the earth and stars spinning past a close-up of Sandra Bullock as the marooned, panicky astronaut protagonist.”

At that point, I wondered whether the film as a whole could keep up that experimental feeling, with vertiginously wheeling actors combined with an untethered camera swooping around them. Or would the narrative gradually lead us into a more conventional style later in the film? It turns out that, to a remarkable extent, the highly unconventional treatment of unanchored space, where up, down, and sideways characters and background change with a breathless rapidity, extends through much of Gravity‘s length. For brief intervals Ryan enters space capsules and sits, right-side up, and the action calms down briefly. Yet these lead to further scenes in space with the same swooping camera. In short, the film turned out to be as remarkable a formal and stylistic achievement as I had hoped.

SPOILER ALERT. This is not a review but an analysis of the film. Gravity does depend crucially upon suspense and surprise, and I would suggest not reading further without having seen the film.

An experimental blockbuster

I am not the only one who was struck by Gravity‘s resemblance to an experimental film. After the film’s opening weekend in the USA, Variety‘s Scott Foundas published an article on the subject: “Why ‘Gravity’ Could Be the World’s Biggest Avant-Garde Movie.” He references the influence of Jordan Belson’s work on 2001: A Space Odyssey and speculates that the final shot of The Shining echoes the ending of Michael Snow’s Wavelength. More specifically he links Gravity to Central Region, shot in 1971 at in a Canadian mountain range; Foundas describes the robotic arm used to shoot the film and how it was controlled by instructions on magnetic tape. (I’ll have an illustration of the robotic arm in Part 2.) To Foundas, the avant-garde aspects of Gravity outweigh its narrative: “‘Gravity’ has more of a plot than ‘La Region Centrale,’ but only barely, and surely no one is telling their friends to see Cuaron’s film because of its great story. Rather, it’s the very absence of a dense narrative line that gives ‘Gravity’ its majesty.”

I think that to say Gravity has “only barely” more narrative than Snow’s purely abstract film is a considerable exaggeration. The film’s story is certainly simpler and more unconventional than other mainstream Hollywood films, but as we shall see, it contains goals, motifs, character traits, careful setups of upcoming action, and other traits of classical narratives.

In an October 11 blog entry, J. Hoberman also stresses the film’s modernism:

Depth and volume are illusory. Mass has no weight. In this 3-D spectacle, best seen on the outsized IMAX screen, Cuarón promotes sensory disorientation–or better, reorientation. […] Gravity is something quite rare–a truly popular big-budget Hollywood movie with a rich aesthetic pay-off. Genuinely experimental, blatantly predicated on the formal possibilities of film, Gravity is a movie in a tradition that includes D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, Abel Gance’s Napoleon, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, as well as its most obvious precursor, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. Call it blockbuster modernism.

(Actually I’d say Gravity is better than some of these, notably Napoléon and 2001.)

Hoberman sees more of a balance between style and narrative than does Foundas. In fact, he considers that the film contains “a distracting surplus of backstory.” Presumably he would prefer to do without the references to the death of Stone’s daughter and her subsequent aimless car rides after work, listening to the radio. The space voyage does become an overly obvious extension of that drifting and listening, coming close to turning the film into a maternal melodrama. Presumably the filmmakers felt that simply sending Stone on a mission and having her struggle to return to earth was not enough. In interviews, the co-scriptwriters, Alfonso and his son Jonás Cuarón, emphasized that their basic idea was to create a character arc of her “rebirth” after despair. To some, this arc, with its religious overtones, will seem a bit, as Hoberman says, distracting and even contrived. To others it may be inspiring. At least it is not allowed to come forward very often.

Hoberman stresses the balance of plot and radical style. The film, “premised on the absence of up or down, is naturally abstract although it also has a streamlined and suspenseful narrative that, save for one or two ellipses, might almost be happening in real time.” In Variety, Justin Chang’s review highlights the same balance: “at once a nervy experiment in blockbuster minimalism and a film of robust movie-movie thrills, restoring a sense of wonder, terror and possibility to the bigscreen that should inspire awe among critics and audiences worldwide.”

David and I have often claimed that Hollywood cinema has a certain tolerance for novelty, innovation, and even experiment, but that such departures from convention are usually accompanied by a strong classical story to motivate the strangeness for popular audiences. (This assumption is central to our e-book on Christopher Nolan.) Gravity has such a story, though Cuarón is remarkably successful at minimizing its prominence. The film’s construction privileges excitement, suspense, rapid action, and the universally remarked-upon sense of immersion alongside the character in a situation of disorienting weightlessness and constant change.

That construction derives partly from techniques unique to this project. The weightless dance of characters and camera almost entirely does away with such widely applied spatial premises as the axis of action, eyeline directions, and the establishing of stable spatial relationships. And, as Cuarón pointed out in an interview for Wired, “After all, you learn how to draw based on two main elements: horizons and weight.” Those two factors are virtually gone as well.

The weightlessness and the long takes in the film have been given much attention in the press. Reports refer less often to the “Light Box, one of the film’s most extraordinary innovations. It is a giant inside-out LED monitor that allows the film’s own previs special effects to light the faces and bodies of the actors inside the box, making it possible for those shots to be integrated seamless into the effects shots. Basically, apart from the scenes inside space vehicles, traditional three-point lighting is jettisoned along with spatial relations.

Other technical aspects of the film are innovative. A bold new camera mount, the Isis, was devised to allow the camera to twist and whirl around the actors. The silence of space was respected by the filmmaker, leading them to substitute a eerie musical score to replace sound effects and convey emotions. The blocking and acting, of course, had to be vastly different from methods used in conventional films where the actors have the luxury of walking on a ground plane.

In short, it is hard to think of another mass-audience film in recent years that has so thoroughly departed from the current technological and stylistic conventions of mainstream filmmaking. Jurassic Park and The Lord of the Rings, to be sure; perhaps Avatar. Publications devoted to the techniques of cinema have recognized this. The Cinefex issue dealing with Gravity is not yet out, but on the journal’s blog, Don Shay’s remark is quoted: “Every once in a while, a film comes along that is a game-changer. This is one of those films.” Debra Kaufman, writing about the film’s 3D for Creative Cow, agrees: “Anyone who’s seen Gravity 3D will agree that the 3D was a game changer.” And unlike those earlier game-changers, Gravity has a strong experimental component to it that audiences gladly accept, since it is so well motivated by the story and situation.

In the next blog entry, I’ll survey the innovative aspects of Gravity‘s style and technique. Today, though, I’ll concentrate on the plot–in some ways conventional and in some ways quite strange–that holds it all together.

Who needs psychological depth in a crisis?

Arguably Cuarón had constructed nearly the most sparse narrative that can sustain the experimental style and motivate that style enough to hold the attention of a popular audience. Three characters, then two, then one, all with minimal backstories and simple goals.

Most Hollywood films have two parallel plotlines, usually one involving a romance. Here there is only one, and it primarily concerns an immediate situation, a cycle of deadly threats alternating with stages of Ryan’s progress toward safety. On balance, the focus is more on the suspense and terror of the situation than on the characters. Although there is a little mild flirtation between Stone and Kowalski, it’s more to generate humor and defuse the tension than to suggest any real possibility of mutual attraction.

One indication of the film’s minimal characterization is that fact that we never learn the nature of Stone’s experiment. That would be a logical initial goal for her character. Why has she set herself this particular task, which obviously involved not only scientific expertise in a complex field but also elaborate training to become an astronaut? Where does she work? What might her test achieve? Some reviews have referred to her as a medical expert. As far as I can tell, this is based on one line when she and Kowalski are working together to activate the communications device that is her focus of attention in the opening scene. During the calm before the debris collision, she remarks, “I’m used to a basement lab in a hospital where trays fall to the floor.” She also says that “It’s designed for hospital use.” That’s it. Normally a Hollywood film would redundantly give us information about her job. Here we don’t even get a sketch of it. And why is a medical experiment attached to the Hubble Space Telescope?

Incidentally, the Hubble is detached from the shuttle just before the debris cluster reaches it. We never learn whether it, too, is destroyed in the disaster. Might it have survived, with Stone’s experiment, perhaps activated during her brief delay before obeying the mission-abort command? Might she return to earth to find her experiment a success, with her initial goal miraculously achieved despite the tragic events in space. So little is the narrative concerned with the experiment as a significant goal that such questions are unlikely to occur to a spectator. They came to me only after three viewings.

Stone’s casual reference to working in a hospital lab typifies the limited sort of backstory we’ll get for the most part. Aside from Stone’s recollections of her daughter’s death and her aimless evenings of driving as her form of mourning, the moments of backstory are mere hints. In the opening we learn that Matt’s wife left him when he was in space on a mission. Might he be so obsessed with the beauties of space travel because he, too, is seeking to escape loneliness? We can’t know, since he treats the mention humorously, as if he has managed to shrug off his wife’s betrayal. Of the third character present on the spacewalk, Shariff, we learn that he has a wife and son, something revealed by a photo only after his death. This knowledge serves less to characterize him than to contrast this cheerful fellow with the wifeless Kowalski and childless, unattached Stone.

Stone’s mention of her home in Lake Zurich, Illinois and of her daughter’s death is the last piece of backstory that we get, and it comes slightly under half an hour into the film, during the calm interlude when she and Kowalski are slowly traveling toward the International Space Station (ISS). After this, I believe the only scrap of information from her past that we get is that Stone’s daughter had worried about a lost red shoe.

This lack of information about the characters is probably what led Foundas to say that the film has “barely” more of a plot than Central Region. In the same piece, he speculates, did the executives at Warner Bros. “wonder if they’d just gambled away $100 million on the most expensive avant-garde art movie ever made?”

Kevin Jagernauth reports on indiewire that the studio pushed for a more conventionally constructed film. Cuarón told him about some of the feedback he got from WB:

But at first, the studio suggested that [the Mission Control] team in Houston should get more face time. “…there area lot of ideas. People start suggesting other stuff. ‘You need to cut to House and see how the rescue mission goes.'”

And that’s not all. Part of the emotional journey of “Gravity” rests on Stone’s backstory, which includes a daughter she lost, but this is all effectively communicated without breaking the single location concept. However, Cuarón was advised to perhaps include some flashbacks in the film and even more. “A whole thing with … a romantic relationship with the Mission Control Commander, who is in love with her. All that kind of stuff. What else? To finish with a whole rescue helicopter, that would come and rescue her. Stuff like that,” he explained of some of the ideas that were floated his way.

There’s that conventional second romantic plotline, which in the wake of the film’s success seems such a ludicrous suggestion. The studio’s attitude demonstrates how very much Cuarón was able to get away with and how much of a struggle it must have been. Audience and critical enthusiasm suggests that he and his team managed to include just enough classical storytelling to make spectators identify with the characters even while knowing very little about them.

Why would a film need to establish psychological depth for characters when most of what they’re going to be doing is struggling frantically for their lives, cast adrift in space and bombarded by hurtling space debris? They must summon what skills and psychological strength they have and get on with it. Thoughtful conversations and subtle complexities are irrelevant for the most part. We need to care about these people to be engaged by the film, but that is part of the point of having Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as the leads, playing to the likeable personal qualities that we already associate with these stars.

Challenges and goals

There’s no question that the characters do have goals, but these are largely based on circumstances thrust upon them rather than on character traits. Before disaster strikes, the characters have short-term goals: Stone to solve the glitch with her equipment (and to avoid allowing nausea to cut short her attempt) and Kowalski to enjoy his final space walk and ideally break the record for duration of space walks. Both goals are cut short by the news of approaching debris and the mission-abort order. As we’ve seen, whether Stone achieves her original goal concerning her experiment is never revealed, nor are we encouraged to wonder even briefly as to whether the Hubble might carry it away from the destruction of the shuttle. Kowalski achieves his goal of breaking the record, in a sense, as he comments ironically while detached and drifting in space and awaiting his death. His space walk will last forever, but records are hardly intended to include corpses.

Once Stone spins off into space, alone, her goal is to re-establish contact with Mission Control and Kowalski. His is to rescue her. Once he finds her and tethers them together, their mutual goal is to get to the shuttle, with Kowalski adding the goal of retrieving Shariff’s body. Very quickly these goals are shattered, since the shuttle has been extensively damaged and its other crew members killed. A new short-term goal arises: reaching the relatively nearby ISS.

Kowalski fails to achieve this goal, since the fuel in his jetpack and his inability to grab anything on the ISS’s exterior send him floating off into space. Stone’s goal is now to get inside before she passes out from lack of oxygen. Once inside, her goal is to detach the remaining semi-functional Suyuz landing vehicle and use it to get as far as the Chinese space station, in turn using its landing pod to return to earth.

Discovering that the deployed parachute has become tangled in the ISS, she takes another space walk to detach it from the Soyuz. Another short-term goal that is soon accomplished. As she starts to remove the bolts anchoring the parachute, she states the short-term and long-term goals: “OK, we detach this, and we go home.”

Her purpose, however, seems to be thwarted when the fuel tank of the Soyuz vehicle proves to be empty. Here Stone loses hope, drifting into despair. She decides to turn off the oxygen supply and allow herself to die. Suddenly Kowalski appears and enters the pod, giving her a pep talk and telling her to use the soft-landing function of the Soyuz rather than its take-off capabilities. He disappears, and Stone, reinvigorated and determined, follows the instructions for landing the craft.

In traditional classical films, shifting goals often mark the turning point between large-scale sections of the plot, generally referred to as acts. Despite its unconventional aspects, Gravity’s plot does stick fairly closely to the well-balanced four-part structure that I have claimed is typical of Hollywood narrative conventions. Not counting titles or credits, the story runs approximately 83 minutes. Thus on average the acts would run about twenty-one minutes each.

At about 22 minutes in, Stone and Kowalski achieve their goal by reaching the shuttle, only to discover that it has been destroyed. At 23 minutes, Kowalski declares them the last survivors of the mission. I take this to be the first turning point, ending the setup and beginning the complicating action. Essential premises are reversed as the pair realize that they are stranded in space and they shift their goal, striving next to reach the ISS. Stone’s failed attempt to contact Kowalski by radio once she enters the ISS–she initially hopes to rescue him–and declaration of herself as the mission’s sole survivor happens at roughly 43 minutes. The third act, the development, begins, with Stone meeting numerous obstacles that threaten her new goal of getting back to earth in the Chinese landing vehicle. The last turning point, launching the climax, comes when Stone awakens from her dream about Kowalski and turns the oxygen flow back on, signaling her return to hope and determination to reach earth. That happens at about 66 minutes in, leaving seventeen minutes for her landing, including the brief epilogue of her floating, swimming ashore, and shakily standing up.

Motifs and causal motivation

As I mentioned, strongly innovative films in the Hollywood tradition need the support of classical conventions to keep the narrative clear and appealing. Two of Gravity‘s most traditional techniques are its motifs and its motivations. Motifs can quickly make the characters more vivid, even if they are not particularly rounded or complex. Motivations often involve planting an object or event in advance. In this film, several motifs trace the relationship between Stone and Kowalski.

In the opening, the motif of Kowalski’s wanting to break the space-walking record is introduced early on, stressing that this is his last mission and hinting that he loves his time in space. Similarly, his anecdotes, introduced with the “I’ve got a bad feeling about this mission” running gag, create irony but also suggest how Kowalski inspires Stone. Before setting out on her re-entry flight in the Chinese landing pod, she repeats this line with the same good humor that Kowalski had displayed. Another parallel is set up between the two when Stone detaches the clasp tethering her to the wildly spinning support in the opening scene, and later Kowalski does the same to separate himself from Stone when they are precariously suspended from the ISS (below). She comes back; he doesn’t.

In the early scene where the pair work to activate Stone’s equipment, he refers to her “beautiful blue eyes,” though she points out that hers are brown. Later, when Kowalski has set himself adrift in space, their radio conversation mentions his “beautiful blue eyes,” which are also brown. Though we see nothing of their earlier relationship, such motifs lend it depth, because we sense that the two have already developed a customary way of bantering with each other.

Similarly, in the opening scene, Kowalski tells an anecdote about how, during a previous mission, he had imagined his wife looking up into space and thinking about him, when in fact she had run off with another man. Later, as Kowalski moves toward the ISS dragging Stone tethered behind him, he asks her if anyone is looking up and thinking about her. This elicits her most intimate revelation, that she had had a daughter who died in a freak accident. There is also no Mr. Stone waiting at home for her. Thus although the two characters have different personalities, both are escaping loneliness by a retreat to the beauty and peace of space.

Finally, there is the last shot, with Stone seen from behind against the sky, covered by light clouds. It reverses the opening, when we were in the opposite position, looking down at the earth from space, with the clouds of a huge hurricane prominently visible. There Stone drifted in space, held in place by a large mechanical arm; here she struggles to regain her sense of balance after prolonged weightlessness and succeeds in walking a few steps, thanks to gravity.

Like motifs, careful motivation of action helps us navigate through the plot. Given the rapidity with which new information is thrown at us as the narrative progresses, the screenwriters are careful to set up major premises in advance so that we will quickly understand them when they arrive. In the opening scene, as Kowalski swoops cheerfully around the shuttle, Houston asks about the supply of fuel in his jetpack. He reports that it’s 30% down. Not a lot, but enough that we are prepared for the moment after the disaster when he says he’s running “on the fumes.”

During the opening, the messages from Mission Control thoroughly forewarn us of the rapidly approaching hail of space debris. After it passes, Kowalski has Stone set her watch for 90 minutes, since that is when they can expect the same debris to return–as it does at regular intervals to destroy the ISS and the Chinese station. Stone reminds us of this danger when she exits the Soyuz vehicle to detach its parachute, muttering, “Clear skies with a chance of satellite debris.” The presence of the deployed parachute also sets up the moment when the chutes of the Chinese pod deploy as it nears its splashdown in the final sequence.

As Stone struggles to get aboard the ISS, Kowalski converses with her via radio. They mention her training with landing vehicles. Her only experience has been with simulators, and in every case she crashed them. Still, as Kowalski points out, she knows something about them–a point which proves vital in the dream scene discussed above, where Stone’s mind summons up a memory about how launching and landing space vehicles are not all that different.

Apart from creating a brief scene of suspense, the fire in the ISS introduces the fire extinguisher and demonstrates how, in a situation of weightlessness, the extinguisher propels Stone through space. This prepares us for the crucial scene in which she uses it as Kowalski had used the jetpack, allowing her to reach the Chinese station despite being untethered in space.

Character motivation, fortuitous events, and religion

Throughout the film the cause-effect chain remains fairly straightforward, with one major exception that I’ll get to shortly. But because the characters are reacting to rapidly changing circumstances almost entirely beyond their control, the outcomes are often fortuitous rather than the result of character traits. This is not to say the film uses numerous coincidences. It is not coincidence that Stone manages time and again at the last possible moment to grab a pipe or handle on the outside of a space vehicle. She’s aiming to do that, so she manages it not by coincidence but by luck.

Some of the most crucial events in the film are partly a matter of character motivation, but the outcomes of Stone’s and Kowalski’s actions are fortuitous. Stone apologizes to Kowalski for not having immediately obeyed his order to stop trying to repair her equipment and head for the space shuttle. She presumably continued with the rebooting because she is a dedicated researcher, reluctant to abandon her important work even when in physical danger. Yet as it turns out, reaching the space shuttle interior would have been fatal. When Kowalski and Stone do reach the shuttle, they find it split open, its crew dead–just as the pair would be had they retreated inside immediately. Stone’s delay actually saved the pair, though neither character could know this at the time.

Less obviously, Kowalski accidentally dooms himself. We see him in the opening minutes, cheerfully circling the shuttle and Hubble, playing music, telling anecdotes, and apparently hoping to stay outside the shuttle long enough to set a record. Presumably he has already accomplished his task in the space walk, or perhaps as the most experienced member of the team, he is watching over the other two. He is also, however, wasting fuel–fuel that he doesn’t realize he may need. Later, when forced to travel through space to rescue Stone and then to make it from the shuttle to the ISS, his tank becomes empty just before they reach it. His inability to maneuver without endangering Stone leads to him detaching his tether and stranding himself in space forever.

There are other fortuitous events. Stone is lucky that her Chinese pod lands in a body of water but close enough to shore that she can survive the impact and get onto land easily. It is probably by chance that in entering the Soyuz craft, the weightless fire extinguisher blocks the door and that she pulls it into the craft rather than pushing it out. Later the extinguisher enables her to propel herself to the Chinese station. There are also obstacles fortuitously created, as when Stone discovers that the Soyuz vehicle has no fuel–presumably because its supply tank has been ruptured by flying debris.

There may be one major exception to this dependence on accidental causes and effects: the religious motif. This is a strange motif, since it doesn’t become significant to the plot until fairly late. Early in the complicating action, as Kowalski and Stone journey toward the ISS and he asks her about her life on earth, he’s playing a country song, “Angels Are Hard to Find.” It’s playing when Stone mentions her daughter’s death; Kowalski soon turns it off to pay more serious attention to her story. At the time, the song doesn’t seem relevant. About seventy-two minutes in, the religious motif returns and becomes more prominent. Stone discovers that the Soyuz fuel tank is empty. The vehicle drifts as sunset settles on the earth below. We see vast snow fields and fjords below, and frost forms on the window. (The cut to the frosty window is one of the film’s few apparent ellipses.) There is a brief shot of a Russian icon inside the Soyuz (Christ as a child carried by John the Baptist, I think).

Immediately after this, Stone makes contact with someone on earth. She tries to communicate her mayday call. Gradually she loses hope and begins woofing in echo of dogs she hears on the radio. She says she’s going to die. During this scene she talks of how there is no one on earth who will mourn or pray for her soul. She asks the man to “Say a prayer for me.” She adds, “I’ve never prayed in my life. Nobody ever taught me how. Nobody ever taught me how.” A baby is heard on the radio, and the man apparently sings a lullaby to it. Stone sadly comments, “I used to sing to my baby. I hope I see her soon.” At that point she dials down the oxygen inflow and says, “Sing me to sleep, and I’ll sleep.”

As she falls asleep, a knock on the door is heard off, and Kowalski enters the Soyuz. He drinks some of the hidden vodka, chats, and tells her to use the soft-landing device. Although he sympathizes with her desire to surrender to the eternal peace of space, he encourages her to save herself rather than giving up: “Ryan, it’s time to go home.” After his disappearance, Stone once again strives to save herself.

Once she has reached the Chinese landing pod, she struggles to cope with its instrument control-panel. As the countdown clock starts running, there is a tilt up to a little Budda figure, roughly in the spot where the icon had been on the Soyuz. As Stone works, she talks to Kowalski, asking him to find her daughter: “Tell her that she is my angel.”

Finally, back on earth, in the final shot Stone struggles to rise, muttering “Thank you,” before walking away from the camera, which tilts up to a low angle of her against the sky.

Though this motif appears late in the film, the narrative stresses it. Something is going on here, but what?

Most obviously, Stone seems to become somewhat religious, despite never having prayed before. Perhaps this is simply an emotional change that allows her to reconcile somewhat to her daughter’s death, to feel hope and enthusiasm for carrying on with her attempts to reach earth, and to accept her survival as a gift to her from some sort of deity.

Given that the startling visit of Kowalski, whom we assume to be dead, to the Soyuz and also his providing Stone with the one bit of information she needs in order to carry on, we might assume that this scene presents a sort of miracle. Kowalski’s visit makes him a quasi-angelic figure bringing divine intervention to Stone, perhaps, or simply a vision inspired by a divine power.

Yet his return is cued as a dream, with Stone falling into a sleep that she assumes will end in death. We all have had some sort of experience with a dream providing inspiration or the solution to a nagging problem. As Kowalski points out, Stone should know that taking off and landing are essentially the same thing; it was part of her training. The dream does not give her the knowledge but rather reminds her of it. Indeed, after she wakes up, she still has to struggle to remember what she learned about soft landings and also consults the manual.

Everything in the dream reflects things we already know about the two characters. Kowalski mentioned knowing where the vodka is kept. Earlier he had reminded her of things she knows about landing from her training with simulators. His words to her about the sorrow of losing her daughter and the temptation to surrender to the eternal peace of space recall her own line from the beginning when he asked her what she likes about space: “The silence. I could get used to it.” (Cuarón, in an interview with Anne Thompson, refers to Kowalski’s return as “a projection of herself in a dream.”)

Seemingly Stone gains some sort of religious belief or spiritual consolation. While working on the Chinese pod’s controls, she talks animatedly to the absent Kowalski, whom she apparently envisions meeting her daughter in an unspecified afterlife. The “Thank you” at the end I take to be the conclusion of this monologue in the pod, thanking Kowalski. In a truly classical film, a character mentioning never having learned to pray would surely say a prayer later in the film. Stone never does. I interpret the religious motif as signaling a transformation of her attitudes rather than implying some sort of divine intervention to rescue her. Either way, some viewers might take this motif to be heavy-handed or saccharine, but its ambiguities could prevent others from having such reactions.

It all worked

The combination of narrative techniques that I have just analyzed obviously appealed to many of the the people who have seen the film.

On November 1, Box Office Mojo summed up the film’s career since its October 4 release:

Through four weeks in theaters, Gravity earned $206.1 million, which accounted for just under a third of total domestic box office earnings in October. It’s already the highest-grossing movie ever to be released during the Fall (September or October) and will earn at least another $50 million before the end of its run.

Gravity‘s remarkable success can be attributed in part to Warner Bros.’s great marketing campaign, which helped the movie set an October opening weekend record ($55.8 million). From there, the movie had an unprecedented second weekend hold thanks to world-of-mouth that asserted the movie needed to be seen on the biggest screen possible (and preferably in 3D). Speaking of 3D–Gravity‘s box office has been pumped up by the fact that most people (around 80 percent) are choosing to pay an extra few bucks to see the movie in that premium-priced format.

According to Variety, “Imax contributed 21% of the opening-weekend domestic cume for the film.”

(Even I, no fan of 3D, have seen it in that format at two of my three viewings so far and would do so again.)

Abroad, the film has also done well. As of November 6, its foreign box-office gross is about $207 million, with the film still to open in several major markets, and its domestic take has risen to almost $220 million, expected to top out at $260 million.

[Nov. 10: Box Office Mojo is now estimating that Gravity will ultimately gross about $660 million worldwide. It opened this weekend in the United Kingdom, where 89% of its ticket sales were for 3D screenings.]

This is also one of those rare films people see in theaters repeatedly within a short period. By the end of its opening weekend, three percent of audience members said they had already seen it more than once. On October 21, the film’s official FaceBook page asked fans, “How many times have you seen the film in theaters?” One, two, or three times were common, but even by that date, two and a half weeks into its run, there were a few who had seen it four or five times. Many single and repeat viewers mentioned plans to see it again. Quite a few also specified which formats they saw it in at the different screenings. Dan Fellman, head of Warner Bros.’s domestic distribution, remarked, “This is a phenomenon where people are asking friends and family not only if they’ve seen the film, but where.”

Some moviegoers (and critics) have found the film boring. But those who love it really love it.

Our next entry will deal with the film’s style and how it was achieved.

Coincidences can play many roles in a film’s plot, as we discuss in this entry. You could take Gravity’s ambivalent gestures toward Stone’s spiritual redemption as another example of Hollywood’s strategic ambiguity about controversial themes.

Jason Mittell has written an essay, “Gravity and the Power of Narrative Limits,” which nicely complements my analysis. He concentrates on the film’s relation to traditional genres, discussing how it departs from familiar conventions of science-fiction and survival narratives.

P. S. 9 November: After I linked to this entry on my Facebook page, Meraj Dhir commented that the song Shariff sings as he does his little weightless dance is from a famous number in Raj Kapoor’s 1955 musical Shree 420. Not exactly relevant to my analysis, but fun to know, so thanks, Meraj! You can see the number here.

NOTE: On November 8, after watching the film a fourth time, I revised this post, correcting a few errors and quoting some brief passages of dialogue that I was able to record on this go-through. I have not noted the changes with the usual strike-through lines, since it seemed too complicated and distracting to do so in this case.

Film-industry pros share secrets in Vancouver

Kristin here:

Even while tempting us with many, many films, the Vancouver International Film Festival runs an event that could all too easily lure us away from viewing and into the world of film-industry gurus: the Film and Television Forum. Its website describes it as “four days of professional development for senior and emerging professionals, from financing to production, to marketing and distribution, to storytelling and engagement.”

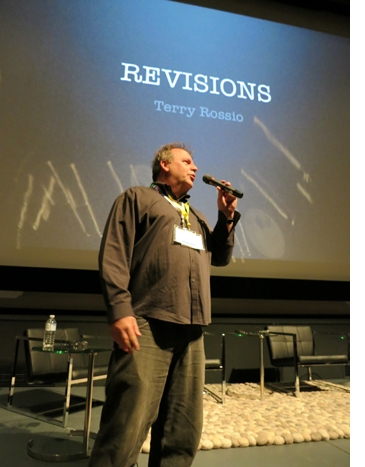

In an ideal world, we would attend all of the sessions, but they run concurrently with as many as eight films showing elsewhere. Two talks were particularly appealing, though, given our interest in the  practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

Terry Rossio

Rossio’s modest title was “Revisions,” though his discussion ranged far beyond advice on how to rewrite a script. He immediately won over the audience, clearly many of them professional or aspiring screenwriters, by passing around a flash-drive and inviting anyone with a script-in-progress on their laptop to put some pages on it. He would end the session by making some impromptu revisions of those pages.

I’m not secretly working on a screenplay or even aspiring to write one, but if I were, I think I would have gleaned some valuable tips from Rossio’s talk.

Most panels and seminars tend to be too general, he said. They “focus on the business side, tell personal anecdotes,” and so on. He feels that it is probably impossible to teach screenwriting: “No, the better question is, can writing be learned?” Yes, but people must teach themselves.

Writing and revising

To Rossio, one crucial thing to learn is that finishing a story is not the end. One should have both doubt and faith: doubt that a story or scene is good enough, and faith that it can be better.

Revision, according to Rossi, is “talent reapplied.” One may have a limited amount of talent for writing, but it can be stretched by reapplying it over and over during the revision process.

Rossio is a big advocate of succinctly creating a strong visual sense in each scene. Even on Rossio’s desktop he comes up with a distinctive icon for each folder (see top): a Rubik’s cube for “Screenwriting,” a little gramophone for “Music,” and so on.

For Rossio, each scene should consist of:

- Opening image

- Key moment (character revelations, reversals, etc.)

- Throw (i.e., the setup for the next scene)

Apart from visual imagery, writing should be situation-based: “Every scene you write must be an obvious situation.” A screenplay is a string of situations, which creates a compelling interest in the scene. His example was two people discussing an important deal in a car on the way to a meeting. The dialogue might become boring because of the static setting, but the writer could make them experience car trouble and have their discussion outside the car while worrying whether they will make it to the meeting: “The easiest way to create interest is through some sort of dilemma.”

One important technique of revision is what Rossio calls “performance dialogue.” Writers tend to compose speeches in full, grammatical sentences, but that doesn’t sound natural in spoken dialogue. Rossio takes these complete sentences and starts to eliminate words: “Less words allows for performance the actor will be performing in between the syllables.” He adds, “If you give an actor a very long line, they can’t manipulate that into an emotion. But a shorter line allows them to express the subtext or nuance of what’s going on.”

This advice led to a question from the audience about how a writer can convey to the director and actors what he or she intended the nuances of a scene to be. Rossio suggested three possibilities:

- Become a director. The director is the one who puts things on the screen. The writer makes suggestions about what to put on the screen.

- Negotiate having the power to be on set during shooting.

- Annotate the screenplay.

The third point caused quite a bit of interest and is an unusual approach that Rossio himself has recently adopted. He writes a normal script, fairly compact and easy to read. But he includes endnote numbers that refer to a separate document, a list of annotations. These might be something like an indication that a certain moment in the film is a reference to the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark or suggestions about special camera angles. Rossio has not used this tactic often enough to gauge whether directors in general would appreciate it, but he did have a good response to the first annotated script he provided.

Rossio dislikes all the screenwriting software on the market, but he showed off a system that he devised himself. The screen below shows the list of scenes for his current project, Masters of the Universe. Each scene is identified by a single word, such as “Vengeance” or “Snake.” The ones that are finished are highlighted in color. (I don’t believe Rossio mentioned the difference between the purple and the yellow highlighting.) The scenes can be switched in order with their labels automatically re-numbered.

One advantage of this system is that the author opens only one scene rather than the whole script. Dealing with something that may be about four pages long is less overwhelming. Rossio also finds that his system facilitates sharing drafts of scenes with a collaborator.

Tips for pitching

In keeping with his emphasis on the visual aspects of a screenplay, Rossio recommends that writers make up a brief pre-viz that captures the essence of the script’s premise. Increasingly, software is becoming available that would allow technically adept writers to create demo clips on their own. For writers unable to do this, Rossio suggests that in a highly competitive market, they should get an effects house to do the job for them. These days even some directors are using this approach in trying to get a job.

Rossio was asked a question about pitching to get a job revising an existing script. He had four suggestions.

First, read the script that is to be revised. Surprisingly, not all writers do that. If it’s based on a literary property, read that, too. A lot of writers just wing such pitch meetings.

Second, take along a presentation board. It can be used for breaking down the script or drawing images.

Third, write a recap of the script as it exists and be ready to discuss specific possible changes.

Fourth, go to the trouble of having two or three specific images ready to show. If the VIPs like the images, they can get access to them only by hiring the writer.

I think if I were a scriptwriter, aspiring or otherwise, I would consider that Rossio packed a lot of useful information into his 75-minute presentation. He also chose two of the script excerpts submitted by audience members and gave their authors some quick and helpful suggestions for revisions.

Walter Murch

As far as I could tell, Murch’s talk had no title, but the concept he threw out early on was “fungibility,” one meaning of which is being capable of changing easily. The example he gave was a caterpillar changing into a butterfly. Murch was referring to the digital revolution in film editing. This was not so much a how-to talk as an attempt to demonstrate the dramatic changes that have come about as a result of rapidly changing technologies.

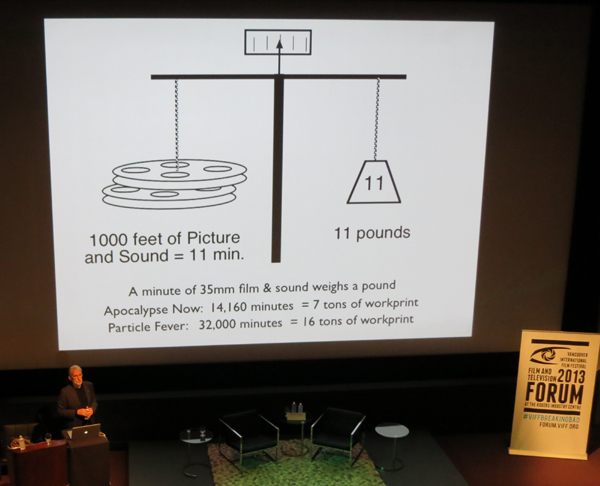

Murch showed a photo of himself struggling with 35mm film strips in editing Apocalypse Now in the 1970s (above). Now, of course, there would be no such physical sorting and splicing. He then pointed out the sheer weight of film, which has been entirely eliminated:

As the graphic shows, a single 1000-foot reel of 35mm film weighs 11 pounds. The strips of Apocalypse Now in the photo above were part of workprint material totaling 7 tons. If Murch’s latest film, Particle Fever, had been edited on 35mm, he would have had to deal with far more, 16 tons of film. It simply would have been impossible to edit such a quantity of footage. (Would a hard-drive with a complete feature film on it weight measurably more than a blank one? he wondered.)

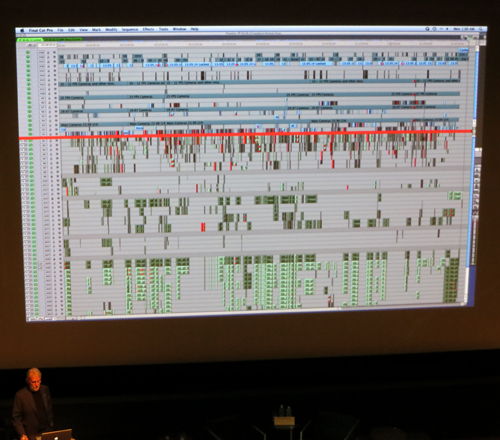

For Particle Fever, Murch used Final Cut Pro 7–an announcement that led to scattered applause from the audience. Like Murch, users of that program are loyal to it, but as he pointed out, a 32-bit program simply can’t keep up with modern demands for memory. While editing, he kept running into situations where there was no memory left, and he had to use elaborate and time-consuming methods to free up storage space. (The film ended up with 18 terabytes of material stored.) On his current project, Tomorrowland, he is using a 64-bit Avid program and has had no problem running out of memory.

(Tomorrowland is being made here in Vancouver, which is presumably why we had the privilege of Murch’s participation in the forum.)

Murch showed a timeline graphic for Particle Fever, with multiple image track, dialogue tracks, effects tracks, musical tracks, and so on. Each small horizontal line represents a separate track:

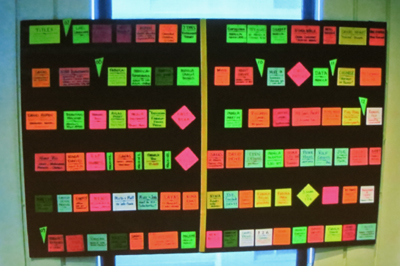

Even while working on this level of complex technology, however, Murch sticks to simple methods for some of his planning. He creates a “scene board” using cards coded with colors, sizes, and shapes . The little green triangles create a chronology, giving the years covered by each set of scenes:

As with Rossio’s system of storing his scenes in a way that allows him to change their order, Murch can move the cards around if the structure of the film changes. Murch put it this way: “I would suggest reversion to kindergarten.”

He also showed some photos of his workspaces for various projects. One was intriguing for indicating how important perspective is for editing. One workroom contained a 50-inch monitor for playing back scenes as he edits them. (See bottom.) Note the little white figures of a man and a woman at the bottom corners of the screen. Murch wanted to keep scale in mind, and the figures represent normal-sized people at the proportionate size they would appear if the monitor were a forty-foot theatrical screen.

This photo inspired someone during the question session to ask whether the increasing tendency for people to watch movies on very small digital screens has influenced Murch’s editing decisions. He replied that it has to some extent, though from the beginning of his career at the end of the 1960s he has had to keep the smaller television screen in mind. Yet he does not edit primarily for the tiny images on mobile devices: “If you cut for the big screen, it will work for the small screen. If you cut for the small screen, it won’t work as well for the big screen.” The Master speaks. So far, the theatrical experience remains the basis for moviemaking.

The Guardian has a video interview with Walter Murch discussing Particle Fever.

A monitor in Walter Murch’s workspace, with two white human figures at the lower corners to indicate scale.