Archive for the 'Film technique: Staging' Category

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

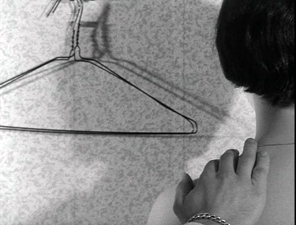

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

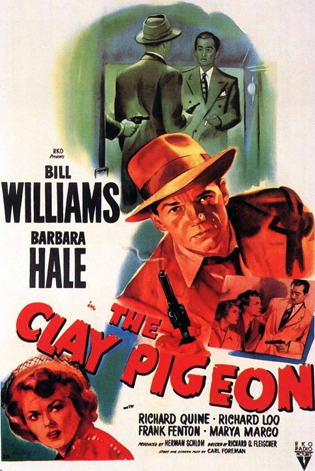

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

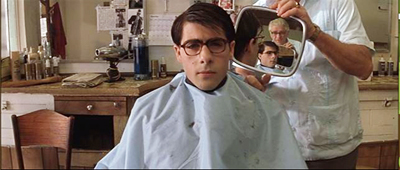

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).

MOONRISE KINGDOM: Wes in Wonderland

DB here:

“An auteur is not a brand,” argues Richard Brody. Not always, I’d suggest; but it can happen. And it’s not necessarily a bad thing.

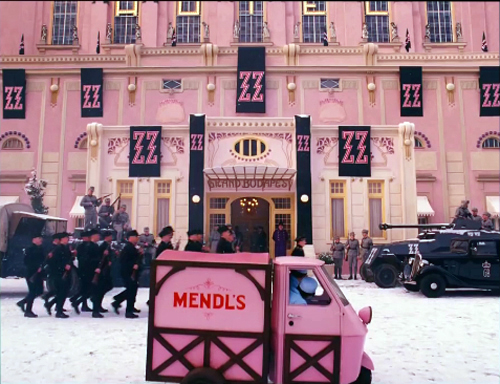

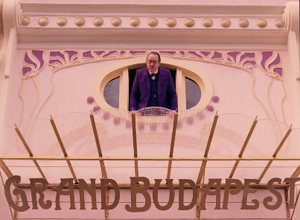

Wes Anderson has found a way to make films that project a unique sensibility while also fitting fairly smoothly into the modern American industry. He has his detractors (“I detest these films,” a friend tells me), but there’s no arguing with his distinctiveness. The Grand Budapest Hotel is perhaps the most vivid example of Andersonian whimsy as signature style.

In any case, before summer’s end I want to look at the auteurish aspects of another Anderson film. Whether you admire him, abominate him, or have mixed feelings, I think that studying this film can show us some interesting things about authorship in today’s film culture.

Toy worlds

When I’m making a movie, what I have in mind, first for the visuals, is how we can stage the scenes to bring them more to life in the most interesting way, and then how we can make a world for the story that the audience hasn’t quite been in before.

A film auteur is often described as having a characteristic tone, an attitude, and recurring themes. But we also find more tangible marks of authorship. One is a tendency to create distinctive story worlds. Hawks gives us milieus filled with stoic, sometimes grimly resigned professionals. Scorsese presents manic, sometimes vicious worlds that encourage his protagonists to go too far.

If the auteur’s story world is the what, plot patterning and cinematic narration give us the how. How are the actions arranged to create an arc of engagement? How are the events rendered in film style—the texture of images and sounds?

It seems clear that no auteur can be absolutely unique; each one works with norms and conventions given by tradition. For instance, a great many US independent films subscribe to the Hollywood convention of the goal-driven protagonist. Moonrise Kingdom accepts it too: Sam and Suzy want to be together, and their aims propel the action. Anderson and co-screenwriter Roman Coppola even give us the classic formula of lovers, kept apart by society, who escape to freedom in the wilderness. Likewise, the film maintains the convention of multiple lines of action: it creates parallels between the idealistic Suzy-Sam romance and the pallid routine of her parents’ marriage, as well as the hint of emerging affection between the phone operator Becky and Scoutmaster Ward.

Like a mainstream film, Moonrise Kingdom is at pains to build the plot toward a crisis—the second elopement of the couple and the massive storm that hits the region. The film turns the storm into a deadline: It will hit, says Bob Balaban’s narrator, “in three days’ time.” And as in a classical Hollywood film, the couple’s problems are solved and we get an epilogue showing their happy, if somewhat covert union.

Anderson has absorbed some lessons from mainstream cinema in more specific ways, I think. Since the Star Wars series (1977-on), we’ve seen Hollywood ever more eager to try “world-making”—adapting the traditions of fantasy, science-fiction, and comic books to creating fairly separate realms governed by their own rules. Batman and Superman adaptations of the 1980s and after followed this line, with Lord of the Rings proving that world-making could sustain long-running franchises (Harry Potter, the Marvel universe).

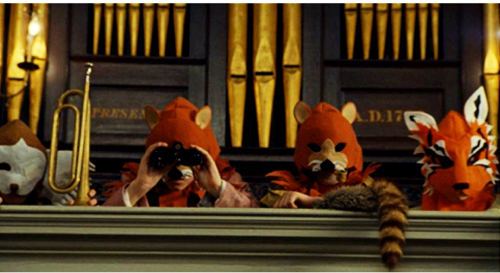

Anderson follows Lucas in creating his own worlds, but outside the conventions of space opera. We can find more or less parallel worlds in The Royal Tennenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, but Moonrise Kingdom may be the most elaborate example. It takes place in terra incognita, a cluster of imaginary islands presumably on the upper Atlantic coast. The name of the primary island, “New Penzance,” reminds us of the fantasy-worlds of Gilbert and Sullivan. There are make-believe Amerindians (Chickchaws) and the Khaki Scouts are parallel to the Boy Scouts, with Accomplishment Buttons instead of Merit Badges. The Scout regalia are given us in the sort of fussy detail that Anderson has long enjoyed.

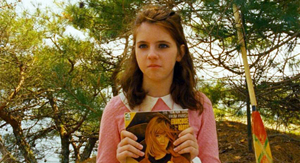

Parts of the story are relayed by a gnome-like Narrator whose range of knowledge includes past, present, and future. He suggests a fairy-tale wizard or bard. An ancillary film tells us that he’s the librarian of New Penzance—the tribal chronicler as small-town administrator. (The existence of this short film serves to reinforce the pretense that New Penzance exists.) Then there are the young-adult books that Suzy carries with her. They’re fictitious but they get strongly tagged to aspects of the action. The books and the scouting gear take on the same solidity as retro details like Suzy’s battery-powered phonograph and Sam’s jar of Tang: 1965 stuff is recruited to flesh out Anderson’s miniature world.

Suzy’s books remind us that New Penzance, like other Anderson story worlds, is redolent of childhood. The film’s opening presents a family’s home as a dollhouse filled with toys and games. Once we’ve seen the fabric pictures rushing past on the walls, the landscapes they preview retain a miniaturized quality.

Those landscapes themselves have a childish defiance of gravity, as when we’re introduced to the poles at the tidal canals and when the Scouts build their tree house improbably high. This motif of top-heaviness eventually yields a sight gag when we learn the implausible fate of Redford’s motorcycle.

Childhood is everywhere. The music we hear in the opening is Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, played by three little brothers on a phonograph and narrated by a child for one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. Throughout the film we hear grownup music designed for kids, such as bits of Bernstein’s rendition of Saint-Saens’ Carnival of the Animals.

Benjamin Britten’s music is central to the film’s soundtrack, from his juvenilia (Simple Symphony, songs from Friday Afternoons) to his later opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream and its chorus of child fairies. A performance of Britten’s church parable Noye’s Fludde is the occasion of Sam’s first encounter with Suzy, and it prophesies the devastating storm of a year later. Carrying this kid-friendly ethos further, Anderson designs his closing credits so that Sam’s voice-over can anatomize Alexandre Desplat’s score, instrument by instrument.

If Britten suggests childhood vitality, the mournful Hank Williams tunes evoke adult disappointment. They’re associated from the start with the lonely, not-overbright Captain Sharp. When Sam’s canoe odyssey is accompanied by the fantasy Williams song “Kaw-Liga,” about a wooden Indian yearning for the carved woman across the street, Anderson suggests a parallel between two lonely, yearning males, and tagging it to Sam prefigures his eventual alliance with his surrogate father.

A tradition of twee

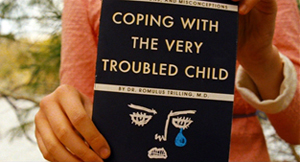

The density of this childish New Penzance, like that of other DIY cinematic worlds, supports a tendency I talked about in The Way Hollywood Tells It. For some time now, filmmakers have been filling their films with details that can be discovered on re-viewing, particularly on the DVD format, which allows us to stop and study a frame. The musical citations I just mentioned can be researched after an initial viewing, and perhaps cinephiles will notice that the therapy book’s cover is a riff on Saul Bass’s credit sequence for Bonjour Tristesse (like Françoise Hardy, a link to Left Bank pop culture).

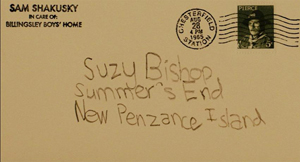

Still, on the first pass we’re unlikely to notice that the stamp on Sam’s postcard to Suzy bears the likeness of Commander Pierce.

Likewise, only after many viewings did I notice that the peculiar flaming-scissors abstraction during the skirmish in the woods is given the same design as that on the motorcycle and helmet of the despicable, and rightfully lacerated, Redford.

And in the epilogue, we might spot that Sam, having cast off his Accomplishment Buttons, has kept his mother’s pin on his new Island Police uniform.

Art and commerce again: What exec could object to loading every rift with ore when it supports ancillary sales to the fan faithful?

Some people find an inward-turned world like this to be fey, coy, twee, infantile, precious, or self-indulgent. It seems to me, though, that Anderson’s work from The Life Aquatic onward links up with a literary tradition we associate with J. M. Barrie and G. K. Chesterton. These writers employed childhood fantasy in an effort to imagine a richer, livelier realm behind prosaic reality. Another kindred spirit would be Winsor McCay, like Anderson an obsessively meticulous stylist who gives heft and lilt to dream worlds. In cinema we might recall Greenaway’s The Falls (1980), as obsessive and precious a project as can be imagined.

Indeed, why not mention the most famous figure of all? There is a trace of Lewis Carroll in Moonrise Kingdom’s looking-glass world—its strangely safe tree house, its deadpan absurdity, the habit of lawyers talking as if always in court. Like Carroll, Anderson doesn’t shrink from cruelty; the death of Snoopy is as perfunctory as that of the oysters on which the Walrus and the Carpenter tearfully dine.

Significantly, modern efforts to reenchant the world are often framed by loss. Wendy comes back from Neverland, Little Nemo awakes with a thump, Alice must return to lazy and boring afternoons. Anderson too evokes the fading of enchantment. Moonrise Kingdom takes place at the onset of autumn, and Suzy’s family lives at Summer’s End. Unlike other modern explorations of faerie, however, this one lets its characters wake up in something approximating their dream life.

Day by day, with interruptions

In accord with the child-based story world, the plot of Moonrise Kingdom provides something of a modern fairy tale. A runaway orphan who retains a token of his parentage heads out for the wilderness. A princess imprisoned in a tower scans the horizon for her rescuer. Lovers exchange messages before they escape into a realm of danger and death. They are rescued by a beneficent authority who will allow them to stay together.

Of course it’s a meta-exercise, since its authors and audiences are self-consciously deploying fairy-tale conventions. But as Barrie and Chesterton and Carroll show, enjoyment of artifice is central to art. Anderson accordingly stylizes both his plot structure and his narration.

He has long been drawn to block construction, building his plots out of big chunks that are often signaled explicitly. In Moonrise Kingdom, the chunks divide up in unusual ways—part, again, of this auteur’s cinematic signature.

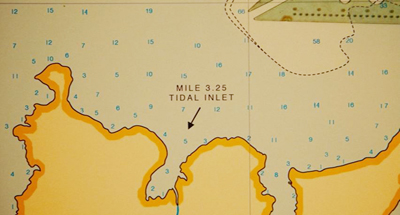

At first we might think we can just track the adventure day by day. On 2 September 1965 Sam goes AWOL from scout camp and Suzy sets out with her belongings. On 3 September the couple fend off their pursuers—the battle of arrow, BB gun, and scissors—and make camp on Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet. There they swim, dance, and spend the night. On 4 September they’re captured and separated.

But that night the scouts help them escape again, and all head for New Lebanon. The “marriage” of Sam and Suzy on the 5th leads to their flight to Saint Jack Wood Island just as the storm hits. Before they can make a lovers’ leap from the church steeple, Captain Sharp rescues them and arranges to be Sam’s foster parent. These four days are sporadically marked by changes from day to night and some remarks, as when Scoutmaster Ward dictates into his tape recorder. An epilogue is reserved for 10 October.

Running athwart the day-by-day divisions are other blocks. Actually, the first day is shown us three times, via shifts in narrational attachment. First we’re with Scoutmaster Ward, his charges, and Captain Sharp, all of whom are searching for Sam. After Ward dolefully ends his audio diary entry (“Let’s hope tomorrow is better”), Anderson cuts to Sam in the stolen canoe.

You might think this scene of Sam paddling is taking place the next day, but actually it skips back to the morning of the 2nd, when he sneaked off. Thereafter we’re attached to him when he meets Suzy in the meadow and they share their first day on the run. Then the plot skips back again to earlier that night, when Mrs. Bishop calls Suzy to dinner and discovers that she’s gone.

The 2 September section is even more complicated than I’ve suggested. When Suzy and Sam rendezvous in the meadow, their encounter is interrupted by a flashback to their first meeting a year earlier (signaled by a title). Later, the Bishop-centered evening section is interrupted by another block, a flashback montage triggered by Mrs. Bishop’s discovery of the couple’s love letters.

Here Anderson provides important backstory paralleling the two kids’ reasons for running away. Sam is bullied by the older boys in the foster-family-compound run by the Billingsleys, and Suzy blows up at her parents and schoolmates. By the end of the third iteration of 2 September, all the major forces in the drama have been delineated.

The two expository flashbacks give us more reason to care about Sam and Suzy in the following scenes, particularly during their skirmish with the Khaki Scouts squadron. Redford’s bullying ways, ignoring Ward’s orders to avoid violence, earn him a lumbar thrust from Suzy’s scissors, and it’s a mis-aimed arrow that wipes out poor Snoopy.

The couple’s idyll, presented as more or less another block, becomes the center of the film. It ends, at the midpoint of the running time, with Suzy reading: “Part Two.”

After they’re captured, Mr. Bishop vows to keep Suzy from Sam. Worse, Captain Sharp learns that Sam is headed for an orphanage and maybe shock therapy. This will encourage Sharp to defend and rescue the two kids at the climax.

With this crisis looming, the plot gives us a sort of nocturne on the evening of September fourth and the dawn of the fifth. In the night, all the players mull over what has happened: Suzy and her mother, Sam and Captain Sharp, Mr. and Mrs. Bishop, and Scoutmaster Ward. But this isn’t merely downtime. The Scouts in their treehouse decide they’ve treated Sam unjustly and set out to help the couple. This decision propels the climax.

By the morning of the final day, Sam and Suzy are reunited and ready for their mock marriage. All that remains is for the storm to disrupt things (even giving Sam some shock therapy by lightning), but also to set things right. The epilogue shows the new stable state of the story world, tying together the plot action neatly. Scoutmaster Ward, reinstated from disgrace, has replaced Captain Pierce’s picture with Becky’s. Sam has a foster father, and he can covertly see Suzy every day.

The magic power of binoculars

Narration involves the moment-by-moment flow of story information, organized around the key question: Who knows what, when?

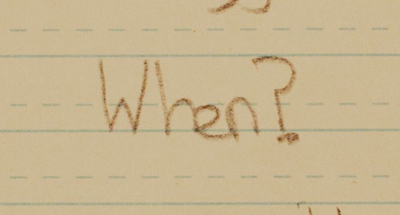

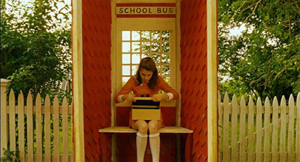

A simple example: Early in the film Suzy finds a letter in the family mailbox. She takes it to the bus shelter and reads it. When she’s done, she looks up resolutely at us and slips the letter into a shoe box.

What was in the letter? The narration has suppressed that information, stirring up curiosity and preparing us for what, many scenes later, Mrs. Bishop will reveal when she finds it: Sam’s final message about their rendezvous. Moreover, the narration flaunts its suppressiveness: She looks at us as if insisting that the message is private.

Unlike the letter scene, which suppresses information, the opening tours of the house give us a fair amount, but we’re not yet in a position to understand it. This applies to our glimpses of the scissors and the New Penzance locations, but there’s also the vertically rising shot showing Suzy’s suitcase in the attic along with her cat peeping out of the fishing creel.

This becomes significant only later, when we realize that Suzy is preparing to bolt.

The narrational process mobilizes film style, both visual and auditory, to engage us in a constant process of expectations—stated, prolonged, fulfilled, or cheated. Consider Suzy’s binoculars. Early in the film we see her looking through them, but we don’t see what she sees. What is she looking at? Or looking for? Soon enough we’ll see that she manages to learn of her mother’s affair with Captain Sharp.

Once we’re set up for the binoculars device, Anderson can use it elliptically. In the meadow we see Sam through binoculars, so we’ll assume that Suzy is looking at him, even if Anderson doesn’t show the customary head-on reverse shot of her.

In effect, this image of Sam is the answering POV shot that has been missing in the early sequences.

But at the climax, when Sam rushes back to camp to fetch Suzy’s binoculars, he’s again caught in their field of view. This immediately leads us to ask: Who’s watching him? Anderson has stuck to Sam in the scene, so we get a gratifying surprise when we learn that the odious Redford has grabbed the glasses and is watching Sam’s search.

Or consider the film’s opening as a narrational gesture. The toy world that the tracking shots present is packed with story information. The very first image shows a fabric version of the Bishops’ house, flanked by Suzy’s left-handed scissors; the picture will soon be echoed by an establishing shot.

Shot by shot, the film channels information in order to set up expectations, to prolong them, to confirm them, or to deflate them. This is how cinematic narration can engage us.

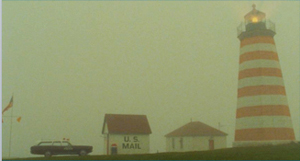

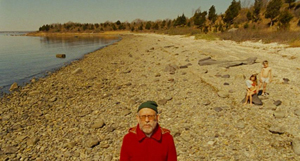

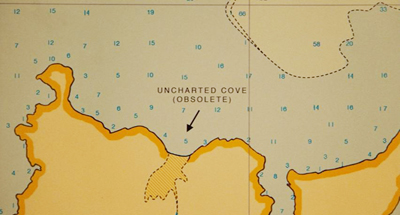

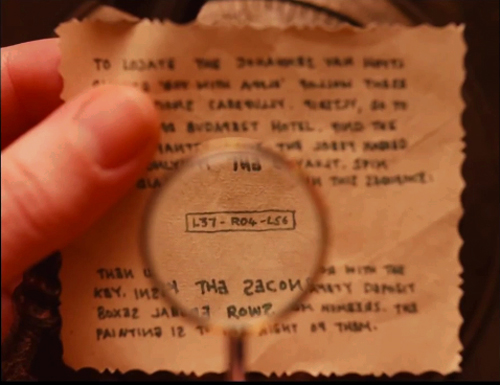

The gnome-like narrator is another source of information. Anderson has compared him to the Stage Manager in Our Town, who can address the audience but also interact with other characters. His opening explanation supplies factoids about this imaginary landscape, while foreshadowing things explicitly (the storm) and implicitly, as with this image that looks forward to Sam and Suzy’s interlude at Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet.

Narration doesn’t just pass along information; sometimes it suppresses it. It can point out when it’s hiding something, as when the film refuses to show us Suzy’s letter. Sometimes information is noticeably incomplete, as when only bits of Suzy’s and Sam’s correspondence are relayed to us. Another instance is the elliptical handling of the Khaki bullies’ attack on the couple, with a glimpse of an arrow and Paul-Sharits-ish flashes of scissors. Only quite a bit after the assault do we see the damage.

At other moments a film’s narration can create an informational gap that it doesn’t fill, only to do so later. During the central idyll Moonrise Kingdom omits a crucial piece of information and puts it in place only at the very end.

Down the aisle and face to face

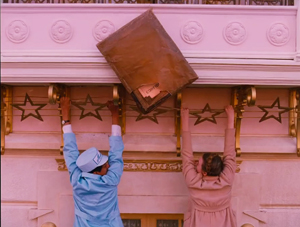

Cinematic narration involves stylistic choices as well, and here again Anderson has sought an identifiable look and feel. In an earlier entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel, I talked about his adherence to planimetric images, the tendency to fix the camera at right angles to a background plane and then arrange figures either horizontally, like clothes on a line, or in profile.

Likewise, Anderseon employs what I’ve called compass-point editing. He usually puts the camera between the characters so that they face us in shot/ reverse-shot.

Or he films the action from straight-on, straight-back, or at a right angle. This geometry can be extended to camera movements: moving lateral and parallel to the planes of the shot, or panning at right angles, or zooming along the lens axis. Another extension is the straight-down angle, which is another variant of shooting at a different right angle to the action.

Planimetric shots and compass-point editing aren’t absolutely new with Anderson, but he uses them more thoroughly than most other filmmakers do. They govern his staging to the extent of pushing him away from realism. How plausible is it that all the Khaki scouts would line up on one side of the picnic table? Or that Ward wouldn’t notice, in a later scene, that all of them are gone?

Anderson’s use of such imagery evokes silent-film comedy, especially the compositions of Keaton, but these shots also suit a fairy-tale world. The stylized naivete of these compositions recalls children’s drawings, which tend to spread figures out against a flat background. (This was prefigured in the squashed perspective of the Bishop house as portrayed in the fabric picture.)

When a director commits to a particular style, he or she may have limited choices on other fronts. A good example is the climactic confrontation of all the adults in the St. Jack Wood church. Anderson might have staged this in many ways, but his stylistic preferences make the central aisle the most feasible arena. So we get the groups facing one another, in reverse-angle depth, moving from one planimetric composition to another, the cutting being either 180-degree reverses or simple axial cuts (zero-degree changes of angle). Sometimes the actors pivot to provide foreground profiles and frontal faces in the distance.

Once you the filmmaker embrace such a marked style so thoroughly, how can you signal special moments? In Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson does this by reverting to more commonplace technical choices.

When Suzy and Sam meet in the dressing room in 1964, we get straightforward 180-degree reversals.

And when they re-meet in the meadow, we get a mixture of profile and head-on shots.

But then Anderson starts to exempt them from the usual spatial strictures. The correspondence montage, for instance, retains the perpendicular framing but decenters his protagonists in mirror-image fashion.

As they get to know one another on their camping trip, the facing-front staging becomes less severe, more modulated.

And finally, when they admit their love to each other, Anderson gives us conventional ¾ views of faces and over-the-shoulder angles. These setups are reiterated when they embrace and dance.

At an emotional peak, Anderson sharply violates the film’s intrinsic norm by bringing in a common technique—which now gains a force it doesn’t customarily have.

Summer’s end

The epilogue recapitulates both narrative and stylistic features. There’s another lateral tracking shot of the Bishop house, but now Sam is painting in a space that was empty at the start.

Again Suzy is using her binoculars, but now, dressed in cheery yellow, she has something worth seeing.

On the soundtrack we hear Britten’s “Cuckoo” song, a reiteration of the summer’s-end motif. The cuckoo, born in spring, enjoys the summer but must eventually fly. As we hear this over Sam’s departure through the window, Anderson’s camera slides down to reveal that Sam’s picture presents a landscape that has now vanished.

Here is the big ellipsis that Anderson didn’t flag in the central idyll. When Sam was painting a stretched-out Suzy at Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet, they had agreed that the name of the place was insipid. She says she’ll think of a new name. But we’re told no more about the matter. In the epilogue, when we see Sam’s picture, we realize that they have given the place a better name: Moonrise Kingdom, inscribed in white on the shore.

“This is our land!” Sam had shouted when they looked out at the inlet. Like Anderson’s imagining of a parallel world of childhood, Sam has recreated, in the manner of modern fairy tales, something that is gone. As if in sympathy with the gesture, the film’s closing shot updates one that was given us during the scenes on the shore, with the yellow pup tent now pitched as the mist rolls in.

Did the couple really write MOONRISE KINGDOM on the shore during their stay? Hard to say. What matters is that, provoked by Sam’s picture, the film’s narration concludes by asserting the power of imaginative artifice.

Selling directors

Floating Real Scarab Beetle Earrings.

Thinking about auteurs has always obliged us to focus on the interchange between industrial demands and artistic aims.

In general, I don’t see an inevitable conflict between market demands and artistic expression. (I argue for this here and elsewhere.) True, often producers and executives and censors mangle creators’ efforts. But some directors know how to do what they want with what they have. For example, Hitchcock’s artistry benefited from his status as a celebrity director. He won substantial budgets and greater control of his work. And sometimes the suits’ demands improve a film (as I suggest here).

Historically, it isn’t easy to separate auteurs from their brands. Let’s assume that a branded auteur is one who is known to a broad public for certain qualities of his or her films. A simple measure would be an ordinary viewer saying “I like X movies,” where X is the name of the director.

Hitchcock is nearly everybody’s clear-cut example of an auteur, but by the time the Cahiers du cinéma critics were forging their conception of cinematic artistry, Hitch was a brand too. How else to explain the 1940s-1950s book collections bearing his name, or The Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, or the tag, “The master of suspense”? Hitchcock participated in this image-building with his jokey interviews, his walk-on appearances in his movies, and his reputation as a bland-faced prankster. Few directors today foster such shameless self-promotion. Also branded were Chaplin, Disney, Welles, and Cecil B. DeMille. Among the cinephilic public there was recognition of Huston, Sturges, and a few other hands.

Hitchcock is nearly everybody’s clear-cut example of an auteur, but by the time the Cahiers du cinéma critics were forging their conception of cinematic artistry, Hitch was a brand too. How else to explain the 1940s-1950s book collections bearing his name, or The Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, or the tag, “The master of suspense”? Hitchcock participated in this image-building with his jokey interviews, his walk-on appearances in his movies, and his reputation as a bland-faced prankster. Few directors today foster such shameless self-promotion. Also branded were Chaplin, Disney, Welles, and Cecil B. DeMille. Among the cinephilic public there was recognition of Huston, Sturges, and a few other hands.

Of course many of the auteurs discovered by the Cahiers critics were unknown to the public at large, and they didn’t make profitable pictures. In 1940s Hollywood, the successful Lang was Walter, not Fritz. But as the film industry developed, and as auteur criticism became prominent, directorial distinctiveness became a marketing angle. By the 1970s, the movie brats, along with older hands like Altman, were presenting themselves as having “personal visions” carried by their films.

More recently, US independent cinema has come to depend on several appeals (sex, social comment, and the like), but surely authorship is a central one. The indie scene exploits the signatures of directors as different as Lynch, Jarmusch, and Paul Thomas Anderson. The emergence of younger talent like Nicholas Winding Refn and Kelly Reichardt conforms to a similar pattern; people follow and support emerging directors, and distributors publicize the films that way. No wonder James Schamus, founder of Good Machine and late of Focus Features, once remarked: “I’m in the business of selling directors.”

This is just a fact of life for ambitious independent filmmakers. Wes Anderson’s cultivation of a distinct style is probably partly a genuine reflection of his personality and partly a matter of willed self-presentation. But of course we’re all indulging in self-presentation, using Goffman’s “impression management,” every time we interact with others.

Like an indie band, Anderson has created a marque unusual enough to let the fans feel they’re in on something keyed to their nonconformist tastes. He has provided the usual panoply of ancillary items, like soundtracks and bonus DVD tracks, but he has allowed others to participate in his world. Amateur videos comment on his style; graphic artists render their own versions of his posters. There are dozens of unlicensed Moonrise Kingdom tchotchkes. Anderson’s willingness to permit all manner of “tribute” memorabilia fits the handmade quality evoked by his films.

Like an indie band, Anderson has created a marque unusual enough to let the fans feel they’re in on something keyed to their nonconformist tastes. He has provided the usual panoply of ancillary items, like soundtracks and bonus DVD tracks, but he has allowed others to participate in his world. Amateur videos comment on his style; graphic artists render their own versions of his posters. There are dozens of unlicensed Moonrise Kingdom tchotchkes. Anderson’s willingness to permit all manner of “tribute” memorabilia fits the handmade quality evoked by his films.

Call it Geek Chic if you want, but it exemplifies an important and potentially valuable part of modern popular culture. For such reasons, I don’t see anything inherently bad about being an auteur with marketing possibilities. People don’t seem to object to David Lynch’s coffee and his nightclub. With eccentricity, spontaneous or willed, all is permitted.

My argument assumes that the term “auteur” picks out something neutral. For some people, though, it’s not a description but a compliment; there can be no bad auteurs. But I think we can have both weak auteurs—filmmakers distinguished only by technique or tone or narrative strategy—and downright bad ones as well. I have my own list.

This piece is based on a talk I gave earlier in July at the Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film in Munich. Thanks to Andreas Rost and Michaela Krützen for arranging my visit.

In the New Yorker column I mention, Richard Brody develops an argument along a different line than mine. As I understand it, he’s replying to critics who claim that the auteur approach overrates individual creativity at the expense of collaborators. He’s also objecting to the expanding search for ever more auteurs, who turn out to be minor artisans at best. My remarks are focused on different issues.

For much more on Moonrise Kingdom consult Matthew Zoller Seitz’s indispensable The Wes Anderson Collection. Michael Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture examines Anderson’s cinema as a development of the “Quirky Indie.” The fan-generated merchandise exemplifies what Henry Jenkins, in his book Textual Poachers, called “participatory culture.”

The three-part anatomy of film narrative I use here is explained in greater detail in this chapter from Poetics of Cinema and this blog entry.

My stills showing Sam’s painting and the extreme long shots of the shore can’t do justice to the originals; I tried bigger proportions, but the MOONRISE KINGDOM inscription remains hard to see. I have to assume that most readers have seen the movie, or will. The image below will have to do.

P.S. 21 July 2014: One sign of a distinctive authorial approach is that it can be parodied. James Fiumara writes to recommend the Saturday Night Live parody of Anderson, applying his style to domestic horror. “I frequently show this to students in discussions of both auteurism and genre conventions. The students all laugh at the parody and then I get them to try to recognize what the parody depends on (namely, their recognizing recurring styles and patterns distinct to Anderson films, recognizing the conventions of the horror home-invasion subgenre, and of course seeing the incongruity between Anderson’s films and the horror genre).” Thanks to James for the link.

P.P.S. 12 September 2014: Guillaume Campeau-Dupras writes to point me toward his 2012 blog on the film, which looks at the film from a perspective related to what Kristin and I have written about (but with many original ideas of his own). I think readers interested in Anderson would benefit from his entry.

P.P.P.S. 2 October 2020: The branding continues! See this story about Anderson-style buildings around the world. Here is a filmmaker who has truly changed how people see their environment.

Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image

Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

DB here:

First things first: Happy birthday, Mizo-san! (He was born on 16 May 1898.)

Secondary things second: This entry is based on a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, as part of its comprehensive Mizoguchi retrospective. I want to thank my friends David Schwartz and Aliza Ma for inviting me to MoMI.

A fragile and fragmentary legacy

Mizoguchi, age twenty-eight, and Sakai Yoneko at Nikkatsu studio, 1926.

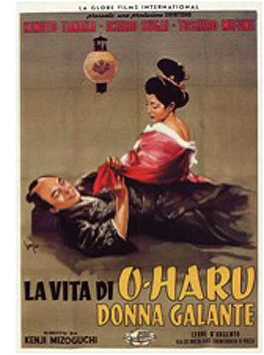

Mizoguchi Kenji’s renown in the West has flowered and faded. Like other Japanese directors, he was unknown in Europe and America before 1950. When Rashomon won the Golden Lion at Venice that year, Japanese cinema sprang onto the world’s radar. Just two years later, Mizoguchi began winning top Venice prizes with Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His old associate Nagata Masaichi saw export opportunities in Japanese costume pictures, especially after Gate of Hell (1953) won the Academy Award, and so Mizoguchi turned out several historical films with high-tone production values. He died in 1956, after Street of Shame (1956), a return to contemporary social commentary.

In just five years, this flare of attention and the praise of the Cahiers du cinéma critics made him second only to Kurosawa in Western recognition. During the 1960s, while Japanese critics were writing him off as outdated, international critics canonized him. Here’s Andrew Sarris in 1970.

I recently saw an obscure Mizoguchi film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art without any English subtitles, which left me up the Sea of Japan without a paddle. The program notes alerted me to the plot outline, but I was generally puzzled by the personal relationships, and the picture dragged along. . . . And then at the end the beleaguered heroine walks to a restaurant on a hillside overlooking the sea, and she orders something from a waiter in white, and the camera is high overhead, and the morning mists are bubbling all around, and the camera follows the waiter as he walks across the terrace to the restaurant and then follows him back to the heroine’s table now magically, mystically empty. It is as if death had intervened in the interval of two camera movements, to and fro, and the bubbling mists and the puzzled waiter provide the Orphic overtones of the most magical mise-en-scène since the last deathly images of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu.

Mizoguchi’s reputation was based almost completely upon his 1950s work. But as ever, film distribution shaped film tastes. Soon after the 1972 success of Tokyo Story in New York, Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films began circulating many major Japanese titles. Most electrifying for my generation was an abundant set of Ozu films, the arrival of which coincided with Donald Richie’s Ozu (1974). Twenty years after Mizoguchi’s emergence, Ozu began his ascent to the top of the pantheon.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

A broader recognition of 1930s-1940s Japanese film was crystallized in the 1978 publication of Noël Burch’s book To the Distant Oberver: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film. Burch urged the case that Ozu, Mizoguchi, and other “mature” directors had done their most ambitious work well before the Western festivals and critics had caught up with them–that in fact the venerated postwar films were mannered and unadventurous compared to the artistically radical prewar work.

Since then, as Ozu (and Naruse, and many more) have risen to the pantheon, Mizoguchi has become quite obscure. Critics haven’t really boosted him much; his most famous film, Ugetsu, ranked 50th in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. Nor is the range of his work easy to sample on video. In 1976, Kristin and I were obliged to go to London to see the early Ozus not in US distribution; now, everything is on DVD. But many years later I went to Brussels for a complete Mizo retrospective, and the rare titles I saw there remain nearly unknown. His festival classics and the “Talbot canon” circulate on good-quality prints and DVDs, thanks to Criterion and Janus. But other films must be hunted down in obscure foreign DVD.

Worst of all, the survival rate of Mizoguchi’s films is appalling (although not exceptional for Japan). He made 43 films between 1923 and 1929; of these, only one survives complete. For the rest of his career he made or contributed to 42 features, of which we have 30. We lack over half his output. The physical quality of what we have varies a great deal, from gorgeous (Genroku Chushingura) to appalling (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937, blown up from a scratched and contrasty 16mm copy). In fact, copies seem to have deteriorated. Prints I saw in the 1970s of Oyuki the Virgin (1935) were in decent shape, but many copies circulating now seem to be bad dupes of those prints, now much battered. There seems to be no systematic effort to restore what we have.

Tears are easy; tragedy is hard

I can’t deny that Mizoguchi’s fluctuating reputation is due to more than availability. He is easier to admire, even to worship, than to love. His films, though visually sumptuous, can be somber and bleak. Often unremitting tales of suffering, they lack humor (though not irony). Ozu’s mix of poignancy and comedy is much easier to enjoy than Mizoguchi’s forbidding, near-tragic despair. Ozu is also a more rigorous stylist; his signature is in every frame. While Mizoguchi was no less distinctive, he was more pluralistic in his technique.

Another obstacle: despite working with melodramatic material, Mizoguchi cools it down, sometimes to the point of remoteness. For many of his films, the prototype was Japan’s shinpa drama, an early twentieth-century theatrical tradition that blended kabuki themes and situations (e.g., the conflict of love and duty) with Western-style dramaturgy. Shinpa plays tended to concentrate on the sufferings of women in a male-dominated society. Shinpa women are victimized, exploited, and condemned; when they sacrifice themselves for men, too often the men attack them, betray them, or dump them. Mizoguchi worked many variations on these plot elements. When the American Occupation demanded more liberal films from the industry, he simply let the oppressed woman win some victory in the end.

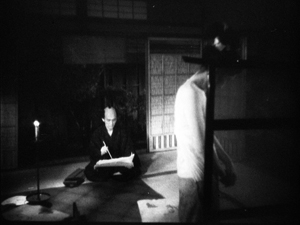

Whether the woman wins or loses, Mizoguchi refuses to beg for tears. Some directors, notably Sirk, amp up melodrama; others, like Preminger, bank the fires. Mizoguchi seems to try to extract the situation’s emotional essence, a purified anguish, that goes beyond sympathy and pity for the characters. In The Poppy (1935), here’s how he renders the moment at which a father and daughter learn that the daughter’s suitor has abandoned her. The core dramatic action is the daughter moving from the foreground to console her father, at which point they embrace.

Some climax! No close-ups, no fast cutting, no camera movement; people withdraw from us and leave us on the outside. All of which suggests that one dimension of Mizoguchi’s artistry consists of exploring how human emotions, notably the unhappier ones, can be expressed in vivid, sometimes surprisingly “cold” pictures.

Pictures tell the story

Everybody grants that Mizoguchi makes magnificent images. He has gone down in history as a pictorialist. But his pictorialism is of a peculiar kind. We tend to think of pictorialist filmmakers as, for instance, masters of landscape, like Ford in My Darling Clementine; or exponents of abstract patterning, like von Sternberg in Shanghai Express; or buccaneers of aggressive depth, like Welles in Citizen Kane.

On each of these possibilities Mizoguchi can match the masters. Here’s a landscape from Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950; this is the scene that made Sarris swoon), a geometrical shot from Hometown (1930), and a bold depth composition from Naniwa Elegy four years before Kane.

It’s not surprising that Mizoguchi relies on the image; in his youth he studied painting (interestingly, Western-style painting at that). But he is, I think, a more fervent pictorialist than his peers.

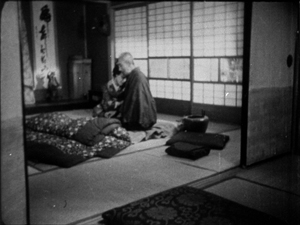

Most movie scenes consist of a story situation mapped onto the space; the style follows, emphasizes, or shapes the story’s presentation. Suppose, Mizoguchi seems to ask, that we start with an image and ask it to become a drama. That’s in a sense what seems to happen with the Poppy example above: a striking picture develops into a story through a suite of compositional changes. Or consider this, from Sansho the Bailiff. A scene starts with a bundle of brush in a village street. Gradually it becomes the site of action: two children peep out, one by one.

Our view isn’t impeded only by the brush. A man bursts eagerly into the frame, blocking the boy and girl, followed by another man. The camera tracks a bit around the foreground post. As the scene goes on passersby will intrude into the frame.

You can’t, I think, imagine many more ways to suppress our views of the kids. We strain to see past all these obstructions, and when the view finally clears and the children are visible and come forward briefly, they turn from us…and more people pass in the foreground.

This is actually an important moment in Sansho the Bailiff: The children, kidnapped from their mother, are about to become slaves. It could be rendered with all the stops out, as a scene of brutality or high tension, but instead Mizoguchi let the dialogue (after some delay) explain what’s happening. At first you might think that Zushio and Anju have escaped from their captors and are in hiding; the unfolding image initially permits that possibility. Eventually, though, the shot, expressing the children’s fear and shame as they shrink from not only the men but the camera, holds us in its own right.

Instead of an image that is a vehicle for the story, the story is gradually born out of the changing image. To some degree, this happens in many films, but not with the persistence and rigor we find in Mizogcuhi. He talked of wanting to hypnotize the viewer, and this is done, I think, as much by the minute changes in the pictures as by the dynamics of the drama.

This version of pictorialism employs several strategies. I’ll mention just three.

Now you see it, sort of

Kiyonaga Toru, Interior of a Bathhouse (1780s).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Traditional Japanese cinema is itself heavily pictorial, from the zigzag excitement of the 1920s swordplay films to the dynamic modernity of the city dramas and the monumental gravity of historical dramas. Directors, I’ve argued in various places, cultivated a “decorative” approach to technique. Composition, camerawork, cutting, and other tactics often created flashier compositions than we find in other national traditions. As early as 1922, Ikeda Yoshinobu was creating arabesques with a bedstead, framing the faces of grieving family members (Cuckoo).

The gridded zones of the Japanese house seems to have invited filmmakers to explore a sort of Advent-calendar style, with bodies framed in different apertures (The Abe Clan, 1938). The same idea could be applied to a bar’s Art Deco wall divider (First Steps Ashore, 1932).

I’ve also argued that this love of pocketed compositions may be an effort to echo similar impulses in Japanese graphic art. The Kinoyaga woodblock print above, with its partial views of women bathing and the little windows through which we see the male attendant watching, is a beautiful example. Perhaps filmmakers adapted this eye-beguiling tactic as a way of giving cinema some cultural credentials (if not a national identity).

Most directors don’t sustain such flashy compositions. The shots function mostly as long-shots or establishing shots, or as in the Cuckoo example, as a series of brief extracts from the larger scene. Mizoguchi drew upon this decorative tradition but let it be sustained through figures moving into and out of the apertures within the frame. He creates a game of vision, a sort of fluctuating pictorial vividness that conceals or reveals or teases us with information.

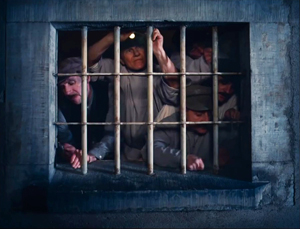

One of the most vivid examples comes in this famous scene from Sansho the Bailiff. Tamaki’s leg tendons are cut, and the other enslaved women are forced to witness it. As the struggling Tamaki is peeled away from the wall and the slavemaster walks to her offscreen, the other women become visible and an older master comes slightly forward in the central square Tamaki had occupied.

As she screams, the grid isolates each woman’s fearful turning away. As with the earlier Sansho scene, dialogue comes to “button up” the unfolding of the image: The old man tells the cringing women that all runaways will punished this way.

The impact of the act is amplified not by, say, cutting to different women’s reactions, but by letting us see them all, simultaneously, in a choreography of terror.

Mizoguchi finds an abundant variety of ways to play his game of vision. Not only are figures and faces secreted in various pigeonholes of the frame, but he can tease us with some that are merely shadows or partial figures (The Poppy; Tokyo March, 1929). Sometimes the key element, such as a character’s reaction, is obscured by a semi-transparent surface, as when the embarrassed model is caught in a corner of a screen in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946).

What other directors treated as piquant flourishes, imaginative ways to arouse our visual interest before moving in to closer views, Mizoguchi saw as a way to activate any cranny of the image and invest it with expression. But for that process to unfold, he needed time.

Intensify and prolong

From the brief surviving fragment of Tojin Okichi (1930).

During the course of filming a scene, if an increased psychological sympathy begins to develop, I cannot cut into this without regret. I try rather to intensify and prolong the scene as long as possible.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Mizoguchi is famous as an exponent of long-take shooting. His earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays the Hollywood-style editing that most Japanese filmmakers mastered at the period. At some point–he says it was while shooting Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner)–he began using a method he called “one scene, one cut.” (Here “cut” apparently refers not to a shot change but to a single take, like a “cut” of meat. Hollywood filmmakers talked the same way sometimes.) That would suggest that he took every scene in a single shot, but actually he didn’t. Most of his scenes are built out of several shots, and throughout his career he would have recourse to standard analytical and shot/reverse-shot cutting for many sequences. He wasn’t as strict about the plan-sequence as, say, the Miklós Jancsó of the 1960s and 1970s was.

Still, he definitely used longer takes than most filmmakers of his day. The shots in most of his post-1935 films average between twenty-five and forty seconds in length, which means that some shots run minutes. Many of his long takes are made from static camera positions, as in the above examples. But he didn’t shrink from camera movements, either tracking shots or crane shots. Kristin and I discuss an example from Sisters of Gion in Film Art, and in his later films he enjoyed establishing a setting with a high-angle crane shot before moving in to details. He also enjoyed riding the crane and directed from it even if the shot was static.

Fixed frame or moving shot, Mizoguchi’s long takes can extract an arc of pictorial-dramatic intensity. That arc can have a clear-cut ABA pattern. In My Love Has Been Burning, the liberal feminist Eiko finds her weak lover Hayase drunk and despondent. He’s no longer the idealist she thought he was, but he defends himself as changing with the times.

Hayase says he’s got some money now and they can marry. When she doesn’t warm to the idea, he attacks her, and suddenly her face gets enlarged, upside down, when he slams her to the floor. This is the first high point of the scene.

They struggle out of frame, but Mizoguchi doesn’t follow them.

Immediately there’s a second assault on our vision: a screen abruptly crashes into the foreground.

After it settles into place, Eiko flees back into the frame, pausing by the doorway. She leaves, and Hayase totters to the same spot looking after her.

The shot has built up to one spike, the image of Eiko on her back, her face close to us, and then to a second, with the collapsing screen. At the end, the site of action returns to the beginning: a figure near the doorway, something else (Hayase, the screen) in the foreground. But in the course of this ABA pattern, the game of vision has concealed as much as it has revealed.

Throughout his career Mizoguchi experimented with the patterning of his long takes, often building them around advances to and away from the foreground, as in these examples. This tactic can be seen in a pure state in the most intense scene of the Occupation feminist film Victory of Women (1946). Here the characters rush the camera and shrink from it as the emotional pitch rises.

Tomo’s husband has just died, and she has already told her friend the lawyer Hiroko that she has no more milk for her baby. Tomo calls on Hiroko, who invites her to come in. The camera obediently tracks back as she enters and sits.

Hiroko, at first oblivious to the distraught Tomo, begins to question her. At first Tomo says that nothing has happened to her baby, and she slides away from Hiroko. She tells her that her husband died the day that they had met in the street. She edges closer to the camera.

Sobbing, she tells Hiroko that the baby is dead; he died sucking her breast. She falls out of the frame and as the camera pulls back Hiroko bends to comfort her. But she also asks Tomo to tell her exactly what happened.

Tomo confesses that staring at her crying baby, she hugged it so close that she may have killed it. As she rises, she cries, “My baby!” And she turns and staggers, like Ayako in Naniwa Elegy, to the most distant point of the set–as if hoping to escape both Hiroko and the camera.

Track in as Hiroko goes back to her, at the spot at which the shot’s action started. Once more the two women advance to the camera, with Hiroko nearly dragging Tomo back to the center. But when Hiroko suggests she go to the police, Tomo slides quickly away from her, back to us, and the camera abruptly pulls back to accommodate her. As when the paper wall crashes into the frame in My Love Has Been Burning, a spike in the drama is accompanied by a second burst into the foreground.

Hiroko rushes to embrace Tomo, assuring her that “You must not run from life, but face it!” Mizoguchi’s staging favors the doubt and fear on the face of Tomo, not the somewhat complacent Hiroko.

As Hiroko hurries off to dress for going out, Mizoguchi’s camera lingers on Tomo, not only pitiable but justifiably worried that she is condemned. As she bends and glances to and fro, Mizoguchi ends the seven-minute scene on an image of a woman with nowhere to turn. This is a terrifying final image: Is this what Hiroko meant by “facing life”?

Some of Mizoguchi’s earlier works go further still. Instead of a coming-and-going pattern, in which the characters confront the camera and then retreat, we get a going-and-going one. The most famous, about which I’ve written probably more than I should, comes in Naniwa Elegy, when Ayako, telling her boyfriend of her sexual infidelity, retreats from him, and from us.

A Western director–Wyler, say, as in The Little Foxes, or Huston–would have put the camera at exactly the opposite point, in the corner of the wall, so that Ayako would advance toward us and Nishimura’s reaction would be constantly visible in the background. It’s as if Mizoguchi anticipated such full-disclosure framing (before these men had even made their films!) and dismissed it as too easy. By suppressing characters’ expressions, he throws our attention onto Ayako’s voice and her posture, while also sustaining some suspense about how Nishimura will respond to her revelations.

Mizoguchi finds a huge variety of ways of turning images into drama, and he has left us a rich repertory of staging strategies–if we only look. Young filmmakers, are you looking?

Filigree

Tanaka Kinuyo and Mizoguchi Kenji in Venice, early 1950s.

[The long take] allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Once Mizoguchi enhances the decorative frame with surfaces and holes bristling with possibilities, and once he sustains it in time through the long take, he can build his scenes out of slight changes in the image–changes that add nuance and expressive depth to the drama. We’ve seen this already in several passages, but I want now to stress how this sharpens our attention and engagement. The restraint of Mizoguchi’s handling (restraint within sumptuousness, I should say) trains us to watch for the tiniest shift in pictorial emphasis. This is the third strategy I want to mention.

In Lady of Musashino (1951), minor changes around the deathbed drive our eye to the profile of the dying Michiko.

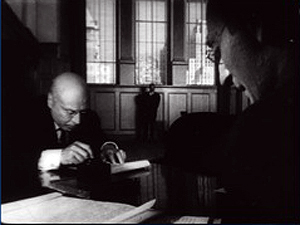

Likewise, when Oishi in Genroku Chushingura reads the master’s poem, sent to his vassals after his suicide, he lowers the paper just a little at the climax, and the gesture is echoed in the men’s slumping forward even more. (This is a movie largely made of just-noticeable differences.)

The just-noticeable differences can be triggered by tiny changes in the avenues of our vision. In Street of Shame, the brothel owner, turned from us in the middle ground, first reveals Mickey and the delivery boy down the left corridor. When he shifts his head, Mizoguchi closes off that view and allows faces and bodies of the prostitutes to fill up the corridor on the right.

Bolder movements can yield even briefer glimpses. When Oharu reads the message from her dead lover, Mizoguchi gives us a “decoy” shot: Her mother stands guard on the left and in the distance we see the door through which the father is expected to come. But the scene’s real action is taking place behind the hanging kimono, where Oharu reacts painfully to the letter. Since we can’t see her, only her wavering voice and the trembling of the kimono convey her emotion. Suddenly she starts to thrash around, her mother leaps toward her, and a tussle ensues. The kimono is pulled down in a heap.

What’s all the fuss? What is Oharu doing? The answer is given to us in an almost subliminal detail, the knife that flashes through the lower right corner of the shot in only two frames on the 35mm print. Oharu races out of the shot, bent on suicide.

So the nuances that spring up may be protracted or simply glimpsed, but either way they become the product of the image giving birth, through its transformations, to the drama. The strategy is just as applicable to closer views as to long shots. In one scene of Woman of Rumor (1954), the keeper of an elegant brothel notices a young man getting cozy with her daughter. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that she hopes to nab Dr. Hatoba herself. As the two talk, Mizoguchi buries Hatsuko in the rear of the scene, her presence signaled by a shadow and her kimono sleeve poking out from a screen.

Mizoguchi cuts directly in and provides a medium-shot of Hatsuko peeking. This might seem safe and conventional, especially in the light of daring choices like those made in Naniwa Elegy. But Mizoguchi now wants to trigger the game of vision around the woman’s face and the edge of the screen. As she listens, he teases us with a little suite of changing expressions and minute gradations of partial blockage–a sort of pictorial vibrato.

As Hatsuko edges out to approach the couple, Mizoguchi switches our attention to small, nervous hand gestures.

Once installed behind the couple, Hatsuko starts the whole process again, from eye-catching sleeves to peekaboo eavesdropping.

Mizoguchi was a fairly pluralistic filmmaker, so the strategies I’ve itemized don’t exhaust everything we encounter in his movies. Sometimes he builds scenes in a fairly orthodox way, with traditional framing and cutting. But taken as a whole, his films offer a magnificent repertory of ways in which the image can, under pressure, deepen and enrich a dramatic situation. Unlike most of today’s filmmakers, he cares about rigor, nuance, and austerity–while at the same time working with scenes of intense emotion. Admire him, worship him, love him, or just respect him: film culture can’t live fully without him.

Thanks, over forty years of viewing, to the Japan Society of New York, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (formerly the Japan Film Library Council), Dan Talbot and José Lopez of New Yorker Films, and the Brussels Cinematek, especially Gabrielle Claes.

The MoMI series runs until 8 June. It begins on 16 May at the Harvard Film Archive and on 19 June at Pacific Film Archive. For Fandor’s Keyframe daily, David Hudson has a varied roundup of response to MoMI’s series.

Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema offer many Mizoguchi films on DVD, some on Blu-ray. See also Criterion’s Hulu Plus offerings. Digital Meme sells DVDs of some early Mizoguchis, with benshi accompaniment; the exasperatingly brief fragment of Tojin Okichi is on volume 2..

My quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” in The Primal Screen (1973), 60-61.

Good clichés will never die as long as journalists need to crank out copy. The MoMI retrospective has revived the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi tug-of-war, this time among New York critics (here and here). Such sideswipe critiques and hosannas can’t really be backed up within the space limits of popular publishing. Moreover, I think that such quick assertions of taste block close consideration of the work. Once you’ve dismissed a filmmaker, you’re unlikely to probe further, and your readers will probably be even less curious. I defected years ago from the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi skirmishes.

The fact that every decade or so Mizoguchi is “rediscovered” through a retrospective indicates his elusive reputation. Among English-language scholars, the 1980s was the big period. Dudley Andrew wrote a still indispensable reference book on Mizoguchi in 1981, and Keiko McDonald offered a penetrating critical survey in 1984. Both volumes, now rare and costly, deserve to be made available in digital editions. Robert Cohen’s two-volume dissertation “Textual Poetics in the Films of Kenji Mizoguchi” (UCLA, 1983) was also significant. Since then, incredibly, we have had only one more overview in English, Mark Le Fanu’s Mizoguchi and Japan, along with an in-depth analysis of some 1930s films, Don Kirihara’s award-winning Patterns of Time. Sato Tadao’s monograph was published in Japanese in 1982, but it’s only recently been available in (a somewhat problematic) English translation (as Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema). Two of my stills are drawn from this book. The French have been more consistently productive, with several studies over the years. A thorough account in Spanish is by the prolific Antonio Santos.

For some background on Western rankings of Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, and Ozu, see this interview with the late Hiroko Govaers. Hiroko was instrumental in bringing many classic Japanese films to Europe and the U.S.

Some of the material in today’s entry comes from Chapter 3, “Mizoguchi, or Modulation,” of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. That offers a much fuller account of what I think Mizoguchi is up to, although today’s blog offers some points and examples not in the chapter. Offshoots of the book’s argument can be found in this online update, and in this blog entry, which compares Mizoguchi with his sort-of-rival Wyler. My oldest piece on the director, “Mizoguchi and the Evolution of Film Language,” in Stephen Heath and Patricia Mellencamp, eds., Cinema and Language (1983), 107–117, contrasts his work with Western practitioners of deep-space staging. Background on the “decorative” impulses in traditional Japanese cinema can be found in Essays 12 and 13 in my Poetics of Cinema, and in early portions of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema.

P. S. 29 June: Thanks to Jeff Fort for correction of a title in the original blog post!

Sansho the Bailiff.

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL: Wes Anderson takes the 4:3 challenge

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).

DB here:

Be shot-conscious! I urged in a blog entry some years ago. I illustrated the point with a tradition of staging and shooting that seemed simple and modest but was actually quite flashy, and even fashionable. Although many filmmakers resorted to it, either often or occasionally, critics hadn’t attended to it. Wes Anderson’s work yielded one of many examples of what I called (swiping from art historian Heinrich Wölfflin) a “planimetric” style.

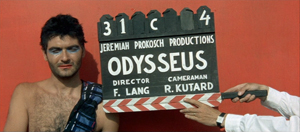

Ideally, you should look at that entry before reading this one. (To encourage you, I link it again. Not for the last time.) Very briefly, this style involves a frontal presentation of the action. You frame people against a perpendicular background, as if they were in a police line-up. Usually you face them to camera, as in this shot from Godard’s Made in USA.

As we’ll see, sometimes you can frame the characters at right angles to the camera, or turned directly away from the camera. Here are examples from Napoleon Dynamite and from Angelopoulos’ The Traveling Players. (Is this the first time these two movies have been mentioned together?)

The key idea is that the people and the setting aren’t observed from an oblique angle; if the background is perpendicular, the people will stand or sit at 90 or 180 degrees to that.

You can arrange them in some depth too, but again, they are stacked in perpendicular fashion, making each area a pretty strict plane. Here’s an example from Pulp Fiction.

One point of my earlier entry is that this is a surprisingly old strategy; Keaton used it occasionally, and Godard was using it heavily fifty years ago. Here are two shots from Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

It has endured in some surprising places. It’s now a go-to option for one-off effects in mainstream cinema. Here are examples from Shutter Island and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013 version).

A few filmmakers make it the basis of an entire film, as I indicate in this entry on Oliveira’s Gebo and the Shadow. And since I wrote the original entry, I’ve drawn on other examples from time to time, particularly from directors who are pastiching Ozu to some degree or another.

Still, Anderson is today the most widely visible example of the style, partly because while others use it sporadically, he is single-minded about it. He has made people shot-conscious (at least when they watch his movies). So after seeing his newest film, I thought it would be fun to think about what distinguishes his approach.

Playing with planes

With the release of The Grand Budapest Hotel, several bloggers have pointed to recurring compositional features, most obviously bilateral symmetry. I’d just add that such symmetry is often used by practitioners of the planimetric approach, with results that sometimes exceed Anderson’s. Here are two shots from Angelopoulos’ Weeping Meadow.

When you think about it, it takes a brave filmmaker (e.g., Godard) to use this approach and not deploy symmetry.

Anderson has used the planimetric approach more extensively in recent years, and he modifies it some distinctive ways. I think particularly of his habit of crowding people together in layers rather than stretching them along a single line. He makes some images look like group portraits or over-posed highschool yearbook shots (The Royal Tenenbaums; Fantastic Mr. Fox).

By employing the planimetric strategy, Anderson gains a somewhat awkward formality, a sense that we are looking from a distance into an enclosed world that sometimes looks back at us. There are as well the sort of comic possibilities that Keaton recognized in Neighbors and The General. A rigid perpendicular angle can endow action with an absurd geometry.

These apparently simple framings often evoke a world of childhood. Just as Kitano Takeshi shows us gangsters behaving like little boys, Anderson’s dollhouse-room frames make adults seem to be toy people arranged just so–like items laid out in a Joseph Cornell box. It’s a style suitable for magical-realist premises like The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and in Moonrise Kingdom it finds its echo in children’s illustrated books.

All in all, then, I have to salute an American filmmaker who thinks about his images carefully and has incited sensitive viewers to notice them. I think we should go further, though. We can ask: How does Anderson, staying loyal to this tradition, vary the look of the shots? And how does he cut them together?

Cutting around

Consider the editing option first. Unless every scene is to consist of only one shot, the question comes up: How do you maintain the style while cutting? Either you make all your cuts axial, straight in or straight back.; or you create a sort of compass-point editing. This can involve cutting 180 degrees, to what’s “behind” the camera in the initial shot. So if characters are confronting one another, the camera is in effect sitting between them as each looks over or through the lens at the other (Ozu’s Late Autumn).

In effect, this option respects the classic 180-degree line, or axis of action, between the characters. It’s just that the camera sits right on that line. Parking the camera on the axis is a common tactic for subjective cutting, showing us first a person looking, more or less at the camera, then what she or he sees from their vantage point. Our example in Film Art: An Introduction comes from Rear Window.

Ozu used this 180-degree reversal often, but not absolutely; he had a more complicated way of conceiving space, and the 180-degree frontal cuts were only part of it. Kitano made a simpler variant central to his early films.

When I asked Kitano why he did it, he explained that it was exactly the way people saw each other in ordinary life. We face each other. He then added that he was such a naive director when he started that it was the only way he knew to set up scenes. We get kindred images in Terence Davies’ work; his frontality may owe something to the Hollywood musical.

Compass-point editing offers another possibility, that of cutting at 90-degree angles to the background plane or the figures’ position. Chantal Akerman does it throughout Jeanne Dielman 23 Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (1975).

Anderson exercises all these cutting options inThe Grand Budapest Hotel. Here a planimetric profile 2-shot yields two frontal shots; we shift 90 degrees and then 180 degrees.

Now here’s a 90-degree shift for the reverse shot.