Archive for the 'Film technique: Staging' Category

The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI

Shokuzai (2012).

DB here:

This year’s trip to Brussels and the Royal Film Archive of Belgium was more low-key than usual. The Cinematek’s mini-festivals were suspended this year, with Cinédecouvertes to resume next summer and the L’age d’or competition to get its own slot in the fall. The usually reliable Écran Total series at the Galeries Cinema was gone, replaced by mostly recent releases. The Cinematek’s main venue was featuring America in the 1980s (not to be despised, but these items were familiar to me) and Antonioni, because of the current exhibition devoted to him in the Musée des Beaux-Arts. And even my archive viewing was slimmed down to only a few days, as I watched some 1940s American features too obscure even to circulate on bootleg DVDs.

I wasn’t exactly bereft of choices, and I could occupy my time preparing for my Antwerp lectures on Ozu, but I was angling for something special. Luckily, our old friend Gabrielle Claes, recently retired as Director of the Cinematek, called my attention to a one-off showing of Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Shokuzai (“Penitence,” 2012) at Cinéma Vendôme, a local arthouse. The bonus: Kurosawa in person! So of course Gabrielle and I went.

Before and after the movie, I began thinking about his career and his place in recent Japanese film history.

Making waves in the 90s

Sonatine (1993).

During the 1990s a new generation of Japanese directors came to international attention. Thanks to home video formats, as well as to a rising taste for international crime and horror films, western audiences became aware of filmmakers from many countries who unabashedly worked in low-end popular genres. The success of Hong Kong films in 1980s festivals had made programmers open to Asian pulp fictions. Soon commercial companies saw a fan market for video versions of movies that were unlikely to get theatrical distribution outside Japan. These films changed forever the image of Japanese cinema as a refined and dignified tradition.

Admittedly, Western views of Japanese film were probably too sanitized. Ozu never shrank from bawdy humor, Mizoguchi could display acute suffering, and Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro were exceptionally bloody by 1960s American standards. Still, things had gotten quite wild in later years. Films that weren’t widely exported, such as those exploiting juvenile-delinquency, yakuza intrigues, and swordplay, as well as the softcore erotica known as “pink” films, would have shown western audiences something quite surprising. In the 1980s, charmers like Tampopo, The Funeral, and other export releases could hardly have prepared audiences abroad for the cinema of shock that was becoming common at home. Perhaps only Ishii Sôgo’s Crazy Family (1984), widely circulated in Europe and America, hinted at what was ahead.

The oldest provocateur was Kitano Takeshi (born, like me, in 1947), who came to directing after a solid career as a comedian. His Sonatine (1993) established him as master of the impassively violent, disturbingly amusing gangster movie. I don’t think anyone can forget Sonatine’s elevator-car shootout, which is unleashed after an awkward, semicomic passage of passengers behaving as we all do in an elevator, adopting neutral expressions and avoiding each other’s eyes. The most celebrated director of this group, Kitano influenced action filmmakers around the world and probably helped spark a revival of interest in classic yakuza pictures.

Other directors were younger and got their start in more marginal filmmaking. Tsukamoto Shinya had worked in Super-8 since childhood and made his breakthrough film, Tetsuo (1989) in 16mm, which became a cult hit on worldwide video. Soon Tetsuo II (1992), Tokyo Fist (1995), Bullet Ballet (1998), and other films showcased a frenetic, assaultive style that was the cinematic equivalent of thrash-rock. Miike Takeshi made several V-films before he hit international screens with Audition (1999), and soon his earlier theatrical releases Shinjuku Triad Society (1995) and Fudoh: The New Generation (1996) became staples of cult screenings and video collecting. Miike pushed things over the edge. Even Kitano did not dare to show a schoolgirl assassin firing deadly darts from her vagina.

I don’t mean to suggest that these directors were sensationalistic all the time. Miike made children’s films, a discreet heart-warmer (The Bird People in China, 1997), a mystical drama (Big Bang Love Juvenile A, 2005), and classical swordplay sagas (Thirteen Assassins, 2010). Kitano developed his interest in prolonged adolescence through sentimental drama (A Scene at the Sea, 1991), Chaplinesque road movie (Kikujiro, 1999), symbolic pageant (Dolls, 2002), and self-referential absurdity (Takeshi’s, 2005, and others). Still, these two directors have often returned to the downmarket genres that launched their reputations.

Nor do I want to suggest that all the filmmakers emerging to wider awareness at this time were roughnecks. Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career in documentary films, followed by the solemn, elemental Maborosi (1995). Kawase Naomi, one of Japan’s few women directors, won acclaim with the sensitive rural drama Suzaku (1997), and Suo Masayuki became a top-grossing export with his satiric comedies Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992) and Shall We Dance? (1996). Yet Kore-eda, widely respected for his nuanced family films, made a movie centering on a sex dolly (Air Doll, 2009), and Kawase had worked for years on autobiographical documentaries dealing bluntly with family tensions, old age, and women’s oppression. Suo’s debut was a pink film called Abnormal Family: My Older Brother’s Bride (1984) in which an affectionate parody of Ozu’s style was used to present copulation, teenage sex work, and a golden shower.

In sum, in Japan the distance between serious art and more sensual, not to say shocking, cinema isn’t that great. To take a more recent example, who would have expected that the director of the quiet, deeply moving Departures (2008; Academy Award, Best Foreign-Language Film) would have learned his craft in a series centering on men who grope women on commuter trains? (Sample title: Molester’s Train: Seiko’s Ass, 1985.)

Mysteries, mundane and supernatural

Shokuzai.

Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s career fits the trend I’ve sketched. Born in 1955, he started with pink films and V-cinema, but the theatrical release Cure (1997) won festival berths and international distribution. It presents the now-familiar mixture of mystery story and supernatural tale, in which a detective with personal problems investigates serial killings and begins to suspect that the murders are performed under some mesmeric influence. In Charisma (1999) the supernatural elements dominate, as a police officer tries to understand the powers of a tree that can magically regenerate itself. Pulse (2001) locates the otherworldly forces in the Internet, where ghosts take over people’s lives and eventually lead humans to flee Tokyo.

Kurosawa’s films became perhaps too quickly identified with what was known as J-horror. His taut, slowly unfolding plots and calm but menacing style did have something in common with the Ring series (1998-2000) that was becoming popular at the time. At the same time, Kurosawa draws on a some story elements common across Asian crime and horror films: revenge, often by a parent or elder figure in the name of a lost child; the suggestion that childhood, especially that of girls, has a corrupt and sinister side; and a sense that modern technology such as computers and cellphones harbor demonic threats. But I think that his films were more thematically ambitious, even pretentious, especially in the case of Charisma, with its ambiguous ecological symbolism. And like his peers, he wasn’t interested only in suspense and shock. His mainstream family drama Tokyo Sonata (2008) attracted western viewers with no knowledge of his spookier side.

The policier aspect is evident from the start of Shokuzai. Originally a five-part TV drama broadcast in weekly installments, it starts with the rape and murder of a schoolgirl, Emili. Her four playmates have seen her attacker ask her to leave the playground with him, so when she’s found dead, the police and Emili’s mother Asako press the girls to identify him. Through fear or trauma, none of the girls can remember what he looked like. Asako summons all four to her home and demands penitence from them in the future—in ways each one must find for herself.

After this prologue, Shokuzai downplays supernatural elements in favor of character studies of the four surviving girls, with a “chapter” devoted to each. The young women live separate lives and their paths don’t intersect; only the implacable Asako reappears in each thread. By the final installment, Asako has more or less given up tracking the killer, but when one young woman accidentally recognizes him, on TV, Asako pursues him and discovers the roots of the crime in her own past.

This is pretty much modern thriller territory, with a whiff of Barbara Vine/Ruth Rendell in the film’s effort to trace how a single event resonates terribly through innocent lives. As with such thrillers, the strength of Shokuzai seems to me to lie largely in characterization and atmospherics. Each young woman is given a distinctive personality, and each one’s professional and personal life fifteen years after the crime is presented with a teasing, hypnotic deliberation. Sae is a meek, sexually immature nurse who is lured into marriage with a rich former schoolmate; his seemingly harmless obsession turns domineering. Maki becomes a schoolteacher herself, and her relentless, demanding methods soon antagonize the local parents—until she unexpectedly proves herself heroic. Akiko has become a hikikomori, a recluse, and is only briefly drawn out of her drowsy existence by the daughter of her brother’s girlfriend. The good-natured little girl in effect reintroduces Akiko to childhood. In the penultimate chapter, the sexual bargainer Yuka seeks to seduce her brother-in-law and to take revenge upon her sister for being their mother’s favorite.

Each young woman is associated with an object or gesture seen in the prologue: a French doll, a bloody blouse, a policeman’s kindly squeeze on the shoulder. At one level, these bits of the past take on psychological impact. The trauma around Emili’s death suggests sources of the grown-up women’s neurotic behavior. Maki, the girl who after the killing rushes frantically through the school looking for someone in authority, becomes an all-controlling schoolteacher. Akiko’s bloody school blouse will find its fulfillment in a brutal crime involving a girl’s toy.

Yet these associations carry extra resonances. It’s partly because of the quietly ominous way Kurosawa films commonplace objects like a ruby ring or a jump rope. Maybe there is a whiff of the supernatural after all, given the unexpected connections revealed between the men in the women’s later lives and the little girls’ fetishes and rituals. Fate plays such cruel tricks that it might as well be malevolent magic.

The demand for expiation and the mother’s implacable intervention in an investigation will remind many viewers of Bong Joon-ho’s Mother (2009, South Korea) and Nakashima Tetsuya’s Confessions (2010). Asako’s characterization gets fleshed out in the fifth episode, which presents two crucial flashbacks leading up to the crime. One even replays a moment leading up to the murder, supplying a previously withheld reverse-shot in the manner of Mildred Pierce’s replay. (Some things don’t change.)

Presumably the recurring flashbacks to the prologue were also motivated by the rhythm of the weekly TV broadcasts. Viewers couldn’t be expected to recall everything from earlier installments.

You can object, as critics have, that the revelations in Shokuzai’s finale are creaky and far-fetched. Raúl Ruiz, in Mysteries of Lisbon, embraces the arbitrariness of old-fashioned plotting, with its felicitous accidents, secret messages, and hidden identities. He scatters these devices freely throughout his story, making them basic ingredients of his film’s world. Instead, Kurosawa introduces most such devices at the last minute, which makes them more surprising but also more apparently makeshift. Still, you can argue that once you eliminate purely supernatural causes for the creepy things we see and hear, audiences will embrace convoluted plots (as again, in Confessions) to rationalize their thrills. As so often in popular narrative, no coincidence, no story.

Quiet elegance

Kurosawa uses long takes, fairly distant framings, and solemn tracking shots to heighten an atmosphere of dread. The questioning of the children is played out in an extreme long shot, refusing exaggeration but conveying very well the flat, obdurate refusals confronting the cop.

In the Q & A after the screening, Kurosawa explained that he didn’t alter his filming style much for the television series, although he found himself writing more dialogue than he would have included in a theatrical feature. His visual technique displays a dry, precise elegance–the Japanese might say it possesses shibui— and it has, as far as I know, no equivalent in current American cinema. The compositions are painstakingly exact, though they’re not as rigidly geometrical as Kitano’s planimetric images and they don’t self-consciously evoke Ozu in the way Suo’s do.

Everything lies in plain sight. The bright, saturated tones of the childhood prologue contrasts sharply with the wan color schemes throughout the present-day sequences.

Kurosawa’s staging has a clarity and point that’s rare today. He often lets significant action unfold without interruption. For example, in Yuka’s flower shop, he gives us a shot lasting nearly a minute. Yuka’s sister has come to voice her suspicion that her husband has had sex with Yuka. Kurosawa moves the two women around the frame discreetly, sometimes hiding their facial reactions, and using the Cross to shift their positions both laterally and in depth. A single step forward can mark rising tension as the sister demands an explanation, and a retreat from the foreground can create a mini-suspense about Yuka’s reaction.

After hiding Yuka’s reaction in the distance, Kurosawa creates a mini-climax by having her turn abruptly to the camera before bending over and sobbing.

Kurosawa saves the cut, as David Koepp might say, in order to ratchet the drama up. In a closer view we can watch the sister, ashamed of her suspicions, consoling Yuka and succumbing to her lies.

Contrary to what proponents of intensified continuity will tell you, you can build an engrossing scene without fast cutting, tight close-ups, and arcing camera movements. Like American directors of the studio era, Kurosawa always knows the best place to put the camera, and he keeps things simple and direct.

Kurosawa’s patient, compact staging has its counterparts in the work of Claire Denis, Manuel de Oliveira, and many other European filmmakers. It’s just that it’s a bit unexpected in the 1990s Japanese iconoclasts. For all their self-conscious extremism, they have wound up reinvigorating certain classic techniques of cinematic expression. This is just one of many reasons to catch Shokuzai on a screen, big or little, near you.

You can see some trailers and extracts from Shokuzai here, but you have to sit through a wretched Peugeot ad every time.

Shokuzai is coming to the Vendôme on 24 July.

On the earthy side of Japanese culture, which I think feeds into the 1990s trends I’ve mentioned, see Ian Baruma’s Behind the Mask.

P.S. 23 July 2013: Adam Torel of the ambitious Third Window Films writes to tell me that the company is releasing Eyes of the Spider and Serpent’s Path on DVD in September. Third Window distributes other recent Japanese films, including items by Miike and Tsukamoto.

Atmos, all around: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Today we have a guest entry by our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. Jeff teaches here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the Film Studies area. He’s an expert on cinema sound, particularly music. His book The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music is a trailblazing explanation of the ties between 1960s Hollywood and the music industry. It combines analysis of scoring with discussions of business decisions that shaped audience’s response to movie soundtracks. His forthcoming book is on how critics have understood the impact of the HUAC hearings and the Hollywood Blacklist, with emphasis on films that seem to comment on Cold War politics.

Jeff has written extensively on sound practices in contemporary American cinema. What better person to explain and analyze the newest sound technology in Hollywood movies?

Director Peter Jackson calls it “the completely immersive sound experience that filmmakers like myself have long dreamed about.” Mark Andrews, who made his feature film directorial debut with Pixar’s Brave, says, “It’s more 3D than 3D images.” “It” is Dolby Atmos, a new cinema sound system that promises to change the way you see and hear movies. Does it?

The buzz

Dolby Atmos made its debut with Brave at last year’s Los Angeles Film Festival. A handful of scenes from earlier films, including Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Incredibles had been test-mixed in the new Atmos system for demonstration purposes. But Brave is the first film to use the new platform from start to finish.

If you haven’t heard of Dolby Atmos, you’re not alone. When Brave opened, there were only fourteen theatres in the country that were capable of showing the film in Atmos. These tended to be high-end movie theatres, such as AMC’s six Enhanced Theatre Experience venues, which typically charge a premium ticket price.

The list of theatres wired for Atmos has grown since then, but the number remains quite small. At this point, there are 37 theatres in the U.S. that feature Dolby Atmos, a tiny fraction of the country’s nearly 40,000 screens. A little more than a third of these theatres are located in California. Approximately another third are clustered in just five states: Florida, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington. Most of these theatres are in the suburbs of major metropolitan areas. True, the recently opened Palms Theatre in Muscatine, Iowa (population 22,886) incorporated an Atmos system in its XL Digital Auditorium, but presumably it was part of its building plan. For existing theatres, an upgrade carries a hefty price tag of between $30,000 and $100,000. So Dolby Atmos may not be coming soon to a theatre near you.

Yet more and more films are being mixed for Atmos. Dolby has announced that more than twenty films will feature the new platform in 2013, a significant increase over the twelve films distributed with this format in 2012. The roster includes three of the most eagerly anticipated studio tentpoles of the summer season: Paramount’s Star Trek Into Darkness, Pixar’s Monsters University, and Warner Bros. Superman reboot, Man of Steel. Still, does the new system justify the expensive theatre conversions and the higher ticket prices that will follow?

Two channels. Then five + one. Now, how about sixty?

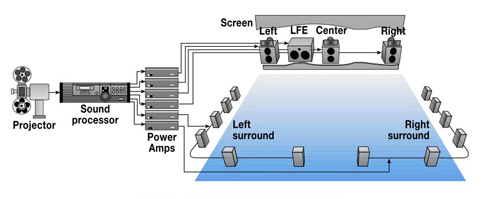

Dolby Digital Surround 5.1.

According to the Dolby website, Atmos grew out of the company’s efforts to introduce Dolby 7.1. For years, the flagship for Dolby’s digital surround sound technology was their 5.1 system. The digit 5 referred to the number of channels that could be used by sound mixers: three channels for speakers behind the screen (left, center, and right) and two channels for all the surround speakers that line the side and back walls of the auditorium (left surround and right surround). The .1 in 5.1 refers to the Low Frequency Effects channel (LFE) that sent sounds between 3 to 120 Hz to a subwoofer located behind the screen in the front of the auditorium. These low-frequency sounds trigger acoustic vibrations that add a kinesthetic kick to onscreen explosions and car crashes.

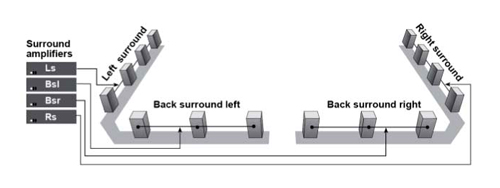

With Toy Story 3 in 2010, Dolby introduced two additional channels to their 5.1 platform. The 7.1 system subdivides the surround speakers. Instead of two channels for the surrounds (left surround and right surround), Dolby 7.1 offers sound mixers four channels (left side surround, left rear surround, right side surround, and right rear surround).

Dolby 7.1 came fairly late to the game, however. Sony already had introduced its own 7.1 system in 1993 with the premiere of John McTiernan’s Last Action Hero. Yet despite the eight-channel capability of Sony Dynamic Digital Sound, (SDDS), it never really caught on, largely because of the added expense of executing a 7.1 sound mix in addition to the standard 5.1 one. To date, more than 1400 films were mixed for the six-channel version of SDDS. Only 97 films received an eight-channel mix.

In the 2000s, Sony gradually began to phase out its 7.1 system. Filmmakers stopped building eight-channel mixes in SDDS in 2007. Moreover, about ten years after introducing SDDS, Sony stopped manufacturing decoders for SDDS content, citing decreased demand. SDDS had always lagged behind its competitors in the battle for screens, so Sony’s decision was not terribly surprising. Although new films continue to be mixed in SDDS to meet the needs of exhibitors that continue to use the system. Most theatre owners have replaced SDDS with one of Dolby’s systems. Sony promised exhibitors it would continue to make parts and service for current SDDS products available until 2014. But the electronics giant acknowledged that it was shifting its attention to digital cinema technologies that were already in development.

Considering Sony’s history and exhibitors’ reluctance to upgrade to an eight-channel system, it’s surprising that in 2010, Dolby would launch its own 7.1 counterpart. But maybe not so surprising, because Dolby’s new channels were differently placed. Sony’s 7.1 system had added channels to the speakers behind the screen. Instead of three front channels (left, center, and right), SDDS had five (left, left center, center, right center, and right). These extra sound sources probably made little difference to most moviegoers. Adding channels behind the screen made for smoother panning of sounds that seem to move across the space depicted in a shot, but it did nothing to increase the sense of spatial immersion.

In contrast, Dolby added its two extra channels to the surround areas. Its 7.1 platform treats the interior of the theatre as seven spatially distinct zones. The additional channels in the surround array enables mixers to position sound elements more precisely. This “zoning” of the surrounds offers mixers a wider variety of options for the placement of sounds, and it more closely approximates the way that sounds in real life come at us from several different directions.

Now Dolby Atmos pushes the premises of this aspect of Dolby 7.1 to the nth degree. While Dolby 7.1 makes a leap from six channels to eight channels, Dolby Atmos makes a leap from eight channels to sixty-four channels, a gigantic change from all of Atmos’ predecessors. Using the old nomenclature that described the sound platform as a ratio of speaker channels to LFE channels, we might call Dolby Atmos a 62.2 system! It offers more than sixty separate and distinct speaker channels as well as an optional channel for additional subwoofers located in the back corners of the auditorium. More importantly, with the vastly expanded number of speaker channels, Atmos enables mixers to position a single sound element in the theatre with unprecedented clarity and precision.

Say you have a screen door banging in the wind. In Dolby 5.1, if a mixer wanted to send that banging noise to the right surrounds, it went to every speaker in the array. In effect, it wouldn’t sound like a single door, but rather several doors banging in unison. In Atmos, however, if a mixer wants to position that banging sound in a particular part of the auditorium, he can treat it in a manner analogous to the way it would be heard in the real world. The sound is emitted from a single point of origin and is heard as a punctual effect rather than as aural ambience emanating from a broader area of the theatre.

All about the panning

Beyond its multiplication of channels, Dolby Atmos addresses certain limitations in earlier platforms. Simplifying a bit, we can say that for content providers Atmos is “all about the panning.” Atmos adds a couple of speakers on each side that are placed close to the screen to facilitate smoother pans for sounds that move from onscreen to offscreen.

The surround speakers in Atmos have a frequency range that closely matches that of the speakers behind the screen. This aspect of Atmos addresses a common complaint about more traditional digital surround systems. In those, the surround speakers have a narrower frequency range than the front ones. As a result, when sounds were panned from onscreen to offscreen, the audience could hear changes in timbre and fidelity. The extra subwoofers in Atmos ameliorate this problem since they help to “bass manage” the surrounds, thereby allowing sounds in them to have a much “fatter” low end.

Besides adding subwoofers to increase the number of LFE channels, theatre owners have the option of adding left center and right center channels to the speakers behind the screen. This allows for smoother pans of sounds made by characters or objects that move across the screen. In this respect, Atmos combines the best features of Dolby 7.1 and Sony’s eight-channel system.

Up in the air

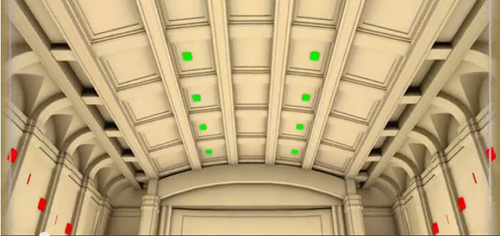

In platforms like Dolby 5.1, sound is situated almost entirely on one plane. The speakers behind the screen are at roughly the same height as are the surround speakers that line the sides and back wall of the auditorium. Dolby Atmos expands the auditory field by adding speakers to the theatre’s ceiling.

These additional speakers create an overhead sound plane, which enhances the sound mixer’s ability to localize sounds in the auditorium. In real life, of course, we hear all kinds of things overhead–bird calls, airplanes, building construction. Although mixers can use these ceiling speakers for sounds that are important in the story that unfolds onscreen, Dolby’s literature usefully reminds us that overhead ambient sound can enrich a film’s setting. A chirping cricket placed in one of the overhead speakers can convey the feeling of sitting at night beneath a forest canopy.

Admittedly, this new feature of Atmos technology merely represents a refinement of something filmmakers could do before. But previous sound technologies suggested an overhead sound plane through a psychological illusion. When the characters in Das Boot, for example, hear the pinging sounds of a British destroyer’s sonar system above their submarine, we might hear that sound originating above our heads. Yet its point of origin is no different from any other sounds that we hear in Das Boot.

Characters’ upturned gazes bias our response as we watch them anxiously awaiting the detonations of the depth charges released by the destroyer.

The extra surround channels and the overhead sources all create a more enveloping ambience and more punctual sound events—ultimately, a more realistic aural environment. Dolby’s innovations should be especially appealing for films projected in 3-D. Atmos, as its proponents note, offers a 3-D sound to match 3-D picture.

Is the recent popularity of 3-D cinema, though, the only factor in Dolby’s push to get more exhibitors on board with Atmos? Curiously, it comes right on the heels of Dolby’s introduction of its 7.1 system. Over the years, Dolby has continually pressed its R & D division to develop new sound technologies. But, in bringing both Dolby 7.1 and Atmos to the marketplace in about a two-year time span, I still have to wonder, “Why now?”

Backward compatibility

Fans of Atmos argue that it represents nothing less than a paradigm shift for cinema sound technology. That may prove to be true if more exhibitors decide to invest in it. But if we are witnessing a paradigm shift, it is one made possible by another paradigm shift, one of even greater historical import. I’m thinking here of the sweeping change that took place as theatres changed to digital projection.

David has written extensively on this topic, and you can find his account of this change in his e-book, Pandora’s Digital Box, a recasting of several blog entries under that name. Actually, the shift to digital projection didn’t demand Atmos. But it certainly made it possible.

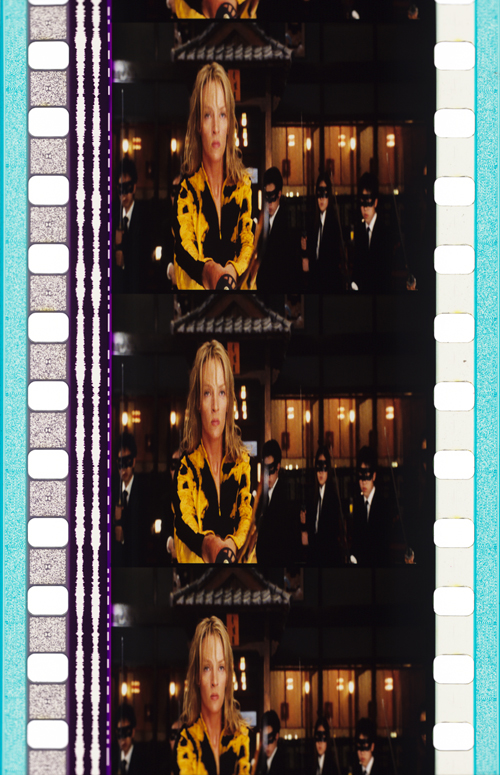

Look closely at a single frame of 35mm film. Like an archeological record, it preserves thirty-plus years of cinema sound innovation. Left of the picture area, you can see the twin optical sound stripes, encoded as wavy lines, that are used for older Dolby Stereo systems. Dolby continually refined its initial four-channel stereo system, ultimately introducing Dolby SR in 1986 as the last generation of its signature noise-reduction technology. (The SR stands for Spectral Recording.) These optical stripes on a 35mm print are still necessary for any theatre still using analog sound.

Just to the right of these optical stripes you can see dashed white lines used for DTS time code. DTS is a digital surround sound technology that uses compact discs to store and play back the film’s audio. The white lines maintain sync between picture and sound.

On the extreme left and right edges of the film strip, outside the perforations, is a speckled light blue stripe. That encodes the audio data for SDDS playback. The information in the two stripes is redundant, but that’s necessary because SDDS is decoded by a sound reader that mounts on the top of a 35mm projector. By putting the information on both sides of the frame, Sony’s design avoids any potential problems in threading the SDDS decoder.

Lastly, in between the sprocket holes on the left side, you can see the audio information for Dolby Digital. Like the SDDS stripes, these gray patches of Dolby Digital audio are encoded as data blocks that are read by a digital sound head. They send the information to a Dolby Cinema Sound Processor.

In our 35mm strip, a huge amount of audio information, along with the film image itself, is jammed into a space that’s less than an inch and a half wide. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, this “quad track” – that is, one analog system and three digital formats – proved to be very versatile. The audio could be played back in any theatre, regardless of the particular type of sound system that is used. The quad track allowed studios to avoid the distribution nightmare of having to match prints to screens using different audio systems. The one-size-fits-all approach also enabled multiplex exhibitors to move a print from one screen to another without worrying about compatibility.

But suppose we had to add another type of audio data to 35mm film, one that is capable of supporting more than sixty different audio channels. There just isn’t enough empty space on a 35mm print to make such an innovation possible. So even if Dolby’s engineers envisioned the potentiality of an overhead sound plane and of a cinema sound processor capable of supporting 64 different outputs, there was no practical way to add the audio information needed for Dolby Atmos and retain the compatibility offered by the quad-track 35mm.

Enter the Digital Cinema Package. With the large-scale conversion to digital projection, the prospect of innovating a system like Dolby Atmos suddenly took on new life. The audio files for Dolby Atmos are embedded in the DCP alongside the files for 5.1 and 7.1. Like the audio in 35mm film, the DCP is designed for maximum compatibility. The Dolby Atmos files are ingested into the theatre’s server along with all of the other audio and picture files found in a DCP. But for any theatre that is not wired for Atmos, the server simply ignores the Atmos files and uses the main audio track file for standard playback. More importantly, if there is any communication problem between the server and the Atmos sound processor, the system simply reverts to a Dolby Surround 7.1 or 5.1 mix, ensuring that a show can continue without delay. Even more impressively, the Atmos system even detects a damaged speaker or amplifier. Its flexible rendering system automatically works around the faulty component, sending the necessary audio data to other parts of the replay chain. So a show will continue despite a technical problem, and a narratively important sound effect or line of dialogue will not be lost due to a damaged speaker or amplifier.

The backward compatibility found in the Atmos system has long been an aspect of Dolby’s business strategy. When Dolby introduced its four-channel Stereo technology in 1975, it did so in a way that accommodated the needs of theatre owners who wanted to retain their existing sound systems. Dolby Stereo used a matrix system that mixed four channels of audio information down to the binaural optical stripes found on a standard 35mm print. After the projector’s sound head read these optical soundtracks, the information contained in them was then sent to a sound processor that “unpacked” the binaural stereo and sent the signals to the appropriate speakers in the auditorium. Dolby’s matrixing system, though, was prone to certain amount of cross-talk between the screen channels, and it occasionally caused a sound to be sent to the wrong output in the four-channel mix.

As a company concerned about backward compatibility, Dolby was willing to live with trade-offs. On one hand, the Dolby matrixing system avoided the kinds of format complications found in multi-channel systems that used magnetic striping. On the other hand, because of the potential for bleed between channels, some sound editors were reluctant to experiment with directional sounds in Dolby Stereo mixes. In practice, the surround channel in Dolby Stereo was reserved mostly for ambient noise, things that added texture to a film’s aural environment but that did not flaunt the precise directionality made possible by multi-channel playback.

Sound historians Jay Beck and Mark Kerins point out that such timidity has also characterized a good deal of sound work in the Digital Surround era. Contemporary sound designers strive to create immersive audio environments for films, but they also opt not to localize specific sounds that would draw our eyes away from the screen. In particular, designers shy away from assigning sudden loud sounds to the rear surround channels. Because the sound originates behind the audience, viewers are likely to be startled, which can be inappropriate to the mood of the story. Worse, the audience may turn to see what caused the unexpected noise. This is called the “exit-door” effect, because it pulls the viewer out of the story as if somebody had slammed the emergency exit.

Sound editors are much bolder about localizing individuated or punctual sounds in an Atmos mix. With 64 different channels to play with, Atmos offers myriad possibilities for audio experimentation. For content-providers, Atmos presents a “brave new world” for cinema sound. But this leads to a larger question: What is it like to see a film in Atmos?

Multi-channel sound with a Scottish lilt

While I was in Los Angeles last August doing research, I decided to spend a sunny Sunday morning at the movies. The City of Angels has a bevy of terrific movie theatres showing Hollywood’s latest, but the choice was easy. I headed to see Pixar’s Brave at Hollywood’s El Capitan Theatre, then one of only ten theatres in the country wired for Dolby Atmos.

El Capitan opened in 1926 as one of three theatres run by legendary showman Sid Grauman. Unlike Grauman’s nearby Egyptian and the famous Chinese Theatre, El Capitan was a venue for live performances. After a decline in attendance in the late 1930s, El Capitan was refurbished and reopened as the Hollywood Paramount Theatre. For several years, it remained a flagship for Paramount Pictures until the late 1940s, when the U.S. Supreme Court and the Justice Department forced all of the studios to divest their exhibition holdings. Until 1991, El Capitan was owned and managed by a series of different companies, including the Pacific Theatres Circuit.

That all changed in the late eighties when Disney offered to lease El Capitan from Pacific Theatres with an eye toward using it as a venue for premiering new films. Disney spent millions restoring the theatre’s original décor, although it seems to have been “imagineered” into a faux 1920s picture palace, complete with a Mighty Wurlitzer organ. Disney also restored El Capitan’s original name perhaps in an effort to sever the theatre from its earlier associations with Paramount. El Capitan is now Disney’s own flagship theatre in Hollywood and is fully integrated with their other businesses. Indeed, the Sunday morning that I attended Brave I was surrounded by families visiting it as one of the stops in Disney tour packages.

As a premium venue, El Capitan offers much more than your usual movie experience. As I walked in to find a seat, a talented organist played a medley of songs from classic Disney films, like Pinocchio’s “When You Wish Upon a Star,” and from more recent titles, such as Toy Story’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” and The Lion King’s “Circle of Life.”

There was plenty of other pre-show entertainment.: a couple of trailers, a brief light show, and song and dance numbers featuring costumed Disney characters. Unlike the organ medley, though, these live performances did not use music from Disney films, but instead drew from the Great American songbook. Mickey and Minnie danced to Astaire-Rogers tunes, followed by patriotic songs, including George M. Cohan’s “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and “The Yankee Doodle Boy.” The program culminated with a short medley of Scottish songs that introduced Disney’s newest princess, Merida.

This final number provided a more or less seamless segue into the start of Brave.

I didn’t know quite what to expect from the film, which has hailed as a change of pace for Pixar, a company that had developed a reputation for targeting a “family film” demographic centered on pre-teen boys. Despite the fact that Pixar had broken new ground with the film’s red-haired, tartan-clad heroine, Brave received middling reviews. By August, it was perceived as a bit of an underperformer, having earned “only” half a billion dollars worldwide. (Such is the high bar set by Pixar titles.)

I quite enjoyed Brave, not least because it was in Atmos. For the most part, Atmos lived up to the hype, offering a sonic experience that was unlike anything I’d heard in theatres before. In a way, Atmos simply refines things that could be accomplished in Dolby 5.1 or 7.1. Yet certain moments of Brave lived up to the promise of a fully three-dimensional sound that matches a film’s 3-D images. I’m not an audio engineer or sound technician. I’m really just a guy who likes going to the movies, albeit one who is a tad more attuned to the vagaries of digital surround sound mixes. So I’m offering some “in the moment” impressions of the Atmos system. If I’ve made any grievous errors in description, chalk it up to either faulty memory or the power of cognitive illusion.

I first became aware of Atmos as something different early on during a rather ordinary scene in which Merida receives “princess training” from her mother. As Merida recites a poem, the Queen, standing above her, instructs her to project her voice saying, “Enunciate! You must be understood from anywhere in the room or it’s all for naught.”

Cut to Merida. When she replies under her breath, “This is all for naught,” the Queen shoots back “I heard that!”

During this brief shot that holds on Merida, Emma Thompson’s mellifluous response as the Queen issues from one of the left rear surround speakers.

The localization of the Queen’s voice creates a brief “point of audition effect” as it realistically places us in the middle of the diagonal space that separates Merida from her mother. The moment also playfully demonstrates the Queen’s instruction to Merida to be heard from “anywhere in the room.”

Another example of Atmos’ innovative use of offscreen sound occurs during the family dinner scene in which Fergus is retelling the story of his confrontation with Mordu. After Merida sits down at the table, Fergus is about to take a bite from a leg of poultry. At this moment, we hear the sound of barking dogs swiftly panned through the right side surround speakers in the auditorium.

The dogs then burst into the frame from off right.

The use of spot sound effects in the surround speakers is quite conventional, but the panned barking had a smoothness and swiftness that I had not heard before.

This moment is interesting for another reason. Although this is admittedly a bit speculative, I believe it showcases Atmos’ ability to exploit a kind of aural correlate of the Phi Phenomenon. The Phi Phenomenon refers to an optical illusion involving the movement of light. Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer noticed in experiments conducted in the early 1910s that when two lights were flashed on and off rapidly enough, subjects saw them not as two flashing lights, but rather as a single light that appeared to move back and forth. Many neon signs exploit this perceptual illusion.

The same is true of this rapidly panned sound in Dolby’s Atmos, which is made possible by the system’s “pan-through array.” Because the sound editor can use positional metadata to send the sound of the bark to each of the right side surround speakers for just a couple milliseconds of time, our mind does not hear it as a group of fragmented sounds, but instead hears it as a single sound that zips through the space of the auditorium.

Later, while galloping in the woods, Merida finds herself thrown into the middle of a Stonehenge-like circle. As Merida gets her bearings, we hear a breathy, echoey, high-pitched sound coming from one of the right surround speakers. Cueing us by Merida’s glance into the space off right, director Mark Andrews cuts to a shot over Merida’s shoulder that shows a blue wisp off in the distance.

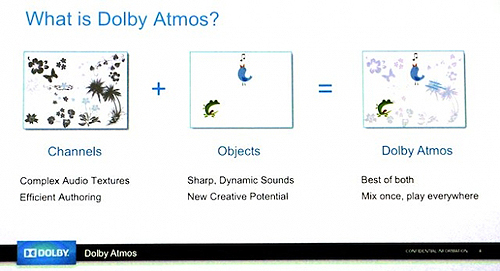

The use of a sound effect in the surround channels to steer our attention to offscreen space may be one of the most conventional aspects of digital sound aesthetics. Yet this moment is a bit unusual. It positions one localized sound effect against a bed of ambient sounds that are sent to all of the speakers in a geographical zone. In fact, this is an aspect of Atmos that Dolby showcases to content-providers. Unlike systems that are wholly channel-based, Atmos allows sound editors to locate a single sound effect in an individual speaker at the same time that other groups of sounds are fed to the system as a channel-based submix. The combination of “beds” and aural objects is captured in a visual diagram provided by Dolby.

The graphic of the bed shows a variety of gray-colored flora and fauna. The aural objects are represented as a green frog and a blue songbird. When the two images are combined, the green frog and blue bird stand out as individually colored objects set off against the bed of gray background elements. Background and foreground effects can all be developed individually and then blended at a later stage of postproduction. Atmos refines the creative possibilities found in other digital surround sound systems in a way that preserves current workflows.

Up until now, I have not said much about Atmos’ ability to exploit an overhead plane of sound. This may strike you as a bit curious since the legendary sound designer, Gary Rydstrom, discussed this aspect of Atmos in the Hollywood Reporter as one of the technology’s most appealing features. Describing a scene where Merida goes to retrieve an arrow that she has launched, Rydstrom says:

You hear the arrow ‘swish’ go through the theatre and land way back behind the audience. Then she goes into the forest. I love putting sound in the ceiling, things like scary forest birds. For a little girl, the forest feels even taller and more imposing if you can have weird sounds way up high.

Rydstrom’s description beautifully captures the way this moment from Brave works onscreen. Yet because I had read his comments before seeing the film, it was a little less powerful than some other events on the overhead sound plane. A moment I found more striking comes when the queen realizes that a magic spell has turned her into a bear. The bear flails about the room, ultimately falling backward onto her four-poster bed.

After falling through the bottom of the bed, the bear then bolts upright to smash through the canopy. Aurally, this moment is rendered as a loud crash located in the speakers suspended from the ceiling. The placement of the sound beautifully punctuates the bear’s sudden upward thrust, adding a sonic punch to the sight gag.

Probably the most vivid demonstration of Atmos’ capability comes in a scene in which Merida is caught in a thunderstorm. Sitting in the balcony of El Capitan, I felt pulled into the thick of events unfolding onscreen. If you shut your eyes, you could almost feel the patter of raindrops, the whoosh of the wind, and the violent clamor of thunderclaps.

Admittedly, such scenes can seem pretty powerful in a theatre using a more conventional digital surround system. A Dolby 5.1 or 7.1 mix can create comparable aural immersion by simply sending submixes of the storm’s sounds to different zones within the theatre. I suspect that the impact of the Atmos mix came less from its ability to isolate particular sound effects than it did from the additional subwoofers placed in the back corners of the theatre. With three subwoofers, loud sounds seem flung at you from all directions. Thanks to the additional LFE channel, the sound waves from those thunderclaps triggered even stronger shakes and rumbles. (The extra subwoofers also enhanced Mordu’s ferocious roars during the epic confrontation, shown up top, that resolves Brave’s plot.) The overhead speakers also played a subtle role in creating the feeling of being caught in a storm. The sense of a three-dimensional environment is undoubtedly heightened by the sound of rain droplets falling and spattering above one’s head.

Is Dolby Atmos the great leap forward for cinema audio that its proponents claim? The answer depends upon the weight you place on potentiality vs. established practice. Atmos definitely creates opportunities for precise placement of sounds in the auditorium. That in turn offers new prospects for audio/visual coherence. As Dolby puts it in the white paper: “If a character on the screen looks inside the room toward a sound source, the mixer has the ability to precisely position the sound so that it matches the character’s line of sight, and the effect will be consistent throughout the audience.”

Yet the specific purposes to which Atmos was put in Brave – the use of spot sounds to activate offscreen space; the use of surround speakers for panned or moving sounds; the creation of a immersive, 3D aural environment; the use of loud noises to viscerally impact the audience – are all things that its predecessors accomplished, going all the way back to Dolby’s pioneering four-channel system. Atmos does these things either a little better or a lot better, depending upon the specific system you’re comparing it with.

Perhaps my description of Brave suggests that the advantages of Atmos are more subtle than spectacular. Perhaps you feel that contemporary movies are sound-polished enough already. If so, Atmos probably won’t hold much appeal for you as a moviegoer.

The bigger question for me is whether it will be widely adopted by theatre owners. A key aspect of Dolby’s sales pitch for Atmos is that it is scalable to almost any size of theatre. If your theatre is too small for a 62.2 configuration, you can reduce the speaker array and get some of the benefits of Atmos’ improved surround definition and overhead sound plane. Dolby says its minimum configuration for Atmos is 9.1. But if the best that you can do for your theatre is 9.1, then perhaps Dolby’s 7.1 system is a more sensible option.

The exhibitor’s ability to mix and match components in Atmos was something I experienced firsthand during a recent visit to the ShowPlace ICON in Chicago. The ICON has two screens wired for Atmos, but those auditoriums weren’t equipped with the optional subwoofers that were in the system at El Capitan. Why? With two additional subwoofers, there is increased risk of sound bleeding over to the neighboring auditoriums of a multiplex. This wasn’t a problem for El Capitan, a huge, standalone theatre.

In any case, the costs to upgrade all the screens in a multiplex would be prohibitive, particularly at a time when many theatre owners are still smarting from expenditures of converting to digital projection. For that reason, Atmos may be introduced as 3D was, with one or two screens per venue at first. The decision to do an Atmos upgrade may devolve upon the question of what particular sound system is good enough to meet the needs of both theatre owners and patrons.

Yet the threshold for “good enough” is not static, and theatre owners may find themselves under increasing pressure as home theatre technologies become ever more sophisticated. If Quentin Tarantino is right that watching digital projection in a movie theatre is like watching a giant television screen in someone’s living room, then Atmos really offers exhibitors something to differentiate the multiplex from the home theatre. With 4K televisions already showing up at big-box retailers, cinema audio may provide exhibitors with the best means of luring movie fans out of their living rooms. After all, are you really ready to deploy a couple of dozen speakers around your walls and from your ceiling?

At several points in this post, I cited information made available in a white paper prepared by Dolby that explains the key features of Atmos to content providers and exhibitors. Additionally, Dolby’s website offers lots of other information about their Atmos system: a list of theaters wired for Atmos, a roster of films mixed in the process, and a short video explaining some of the differences between Atmos and other systems.

Information about Brave in Atmos can be found in two articles published by The Hollywood Reporter that are available here and here. There’s also a video interview with Brave’s sound design team. A brief history of the El Capitan can be found on the theatre’s website.

Film scholars Jay Beck and Mark Kerins both have written excellent histories of Dolby’s Atmos’ predecessors. Beck’s 2003 Ph.D. dissertation, “A Quiet Revolution: Changes in American Film Sound Practices, 1967-1979,” offers a terrific account of Dolby’s innovation of its pioneering four-channel stereo system. For a sampling of Beck’s analysis of Dolby Stereo aesthetics, see his essay, “The Sounds of ‘Silence’: Dolby Stereo, Sound Design, and Silence of the Lambs” in Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound, coedited by Beck and Tony Grajeda. Kerins’ work, on the other hand, focuses more squarely on Dolby 5.1 and what he calls a “digital surround sound style.” See Kerins’ Beyond Dolby (Stereo): Cinema in the Digital Sound Age.

For more on Atmos, see Eric Dienstfrey’s excellent explanation on our UW media blog, Antenna.

Wanda, the biggest cinema chain in China and purchaser of the AMC chain in the US, recently announced a major commitment to Atmos in its Mainland cinemas.

Scoping things out: A new video lecture

A Star Is Born (1954).

DB here:

Cripes! It’s video-lecture fever!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, we do have something new for you.

A video analysis of constructive editing showed up last fall, and a rather long one called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” was posted earlier this year. Now comes one on the aesthetics of early CinemaScope in the US.

It’s a new version of a talk now retired from the lecture circuit and snugly cached on the web. I’m hoping both viewers and filmmakers will be interested in this, particularly in its analyses of staging and composition. The piece makes a more general argument about how new technologies offer both advantages and constraints.

“CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses!” runs about fifty minutes. It’s our first one in HD, so it looks pretty nice on many displays. It could be shown in classes, and I’d be happy if teachers wanted to use it. As with our earlier entries, it’s also available on Vimeo here, where you can leave feedback if you want.

I’m also providing the chapter on Scope from Poetics of Cinema. Think of the lecture as the DVD and the chapter as the accompanying booklet. You can go to the essay if you want to dig deeper into the subject, see other examples of what I’m talking about, or learn the sources for my arguments.

By the way, if you’re interested in the art and craft of widescreen cinema, I’ve posted a web essay on Hong Kong anamorphic here.

As usual, I’m very grateful to my creative tech wranglers Erik Gunneson, who produced the video, and Peter Sengstock. Thanks as well to our web tsarina Meg Hamel.

I’ll have to suspend production of these video lectures for a while, but Kristin and I are hoping to float another novelty soon, perhaps in the next couple of months.

Thanks for everyone who has supported our work through Tweeting, Facebooking, linking, or just telling their friends.

Wild River (1960). From 35mm frame.

“We didn’t have a sense that VERTIGO was special”: Doc Erickson on classic Hollywood

Rear Window (1954); illuminated transparency used to create the lens reflection.

Note: This entry was nearly finished when Roger Ebert died on 4 April. I had intended to send it to him in advance. I think he would want me to post it as I’d planned–just before this year’s Ebertfest.

DB here:

On 17 April, about 1500 people will gather at the Virginia Theatre in Urbana, Illinois, for a celebration of movie love known as Ebertfest. Among Ebertfest’s many guests will be C. O. “Doc” Erickson.

This genial man, who visits Ebertfest each year, is a Hollywood veteran. He was production manager for Alfred Hitchcock, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, Anthony Mann, Roman Polanski, and Ridley Scott. In later years he was associate or executive producer on Chinatown, Urban Cowboy, Popeye, Blade Runner, Looking for Bobby Fischer, Groundhog Day, Kiss the Girls, Windtalkers, and many other projects.

In short, he was an eyewitness to film history. During our visits to Ebertfest Kristin and I have often talked with Doc about his career, and last year I interviewed him for an hour. I thought it was time we set down some of the things we’ve learned. I’ve supplemented Doc’s remarks to us with quotations from Douglas Bell’s 2006 detailed, book-length interview with him.

Setting the scenes

Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Doc began working for Paramount Pictures in December 1944, a year after his graduation from the University of Illinois—Champaign-Urbana. This young man, not yet twenty-one, stepped into the studio that would harbor, across the next few years, The Lost Weekend, The Blue Dahlia, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Unconquered, I Walk Alone, A Foreign Affair, Sorry, Wrong Number, The Big Clock, The Heiress, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, Sunset Boulevard, and several Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Martin and Lewis comedies.

Initially he worked on estimating the budgets for back-lot and set construction. Doc’s unit would try to give the director some leeway. “Ultimately, it wasn’t [a director’s] fault if the set went over budget. . . . We had to try to get enough money in there so that it wasn’t going to go over budget, because then we’d catch hell.” Then Doc and his colleagues would monitor the building of the set to make sure that the specifications were followed and the budget was adhered to.

Doc moved to stage management and supervision, which required him to plan how a production’s sets were arranged in a sound stage. Four or more sets would have to be fitted together, jigsaw-fashion. Doc would try out arrangements by shifting cutout sets on something like a bulletin board, marked with entrances, walls, and power sources. This was called “spotting the sets.” Spotting was much easier in the days of overhead lighting; lighting from the floor, which became more common as the decade went on, posed extra problems.

Once used, the sets might be dismantled, with different departments rescuing what they could use again. A whole set might be saved for another picture (“fold and hold”). B-pictures recycled sets from A pictures. At the other extreme, ornate interior sets might use units drawn from luxurious houses that had been dismantled. From New York mansions came pieces that were shipped to Hollywood and resassembled to create a salon or ballroom.

Paramount’s back lot included big standing sets, including a train station with some cars on the track. “Then, of course, you had pieces of the train in the scene dock, that could be dragged out and assembled on the stage.” A street at the south end of the lot was used for Westerns and featured a mountain that blocked the view of the adjacent RKO studio.

I’ve long been struck by the fact that articles from the classic period seldom talk about the look of sets for ordinary rooms. So I asked: What colors would be found on the sets in black-and-white movies? Doc smiled. “Black and white—or rather, shades of gray.” Sometimes a bit of green would be added. (I’ve read that sometimes snow was painted yellow to make it dazzle.) Pause and think about how hallucinatory it must have looked: actors moving through a three-dimensional black-and-white movie.

The crew was expected to average fifteen to twenty setups per day, at a period when shooting a top-line feature took anywhere from seven to twelve weeks, or even more. The Paramount policy was to press ahead and finish with a set quickly, even if not every shot was taken. Retakes were likely to be close views of the actors and could be picked up later without need for the full set. This flexibility was feasible because most productions were still shot inside the studio walls. Despite the trend toward location shooting in the late 40s, Doc says, “We weren’t off the lot very much.”

The 1940s saw the rise of the hyphenate filmmaker, and this trend was vigorous at Paramount. The studio roster boasted screenwriter-directors Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and several director-producers, including Cecil B. DeMille, Mark Sandrich, Mitchell Leisen, and John Farrow. At Paramount, Doc recalls, “The director was king.” No wonder that one of the most kingly figures of the period wound up there for several years.

A step up

The Misfits (1961).

Doc had moved into the role of assistant unit production manager for Secret of the Incas (1954), directed by Jerry Hopper and starring Charlton Heston and Robert Young. His new job involved managing the day-to-day work of filming as a liaison between the production office and the shoot. A production manager works closely with the assistant director to keep the work on schedule and within budget.

When Hitchcock made his five-picture deal with Paramount and was preparing Rear Window, his assistant director, Herbert Coleman, found that all Paramount’s established production managers had been assigned. Coleman asked Doc to take the job, and Hitchcock approved. Doc’s experience with budget estimating and set supervision made him a natural choice for promotion.

Doc supported Hitchcock on several films, becoming a guest at the director’s home and traveling with him. After finishing Vertigo, Hitchcock shifted to studios that had their own personnel for production management. Hitch offered Doc a place on his television series, but Doc moved on to other Paramount pictures: “I wanted to remain in the feature film world.” He worked in Manhattan with Sidney Lumet on That Kind of Woman (1959). Doc admired Lumet’s meticulous planning of every shot, as well as his insistence on table readings of the whole film before shooting.

Doc then teamed up with John Huston. In 1959 Huston was trying to launch The Man Who Would Be King, and for location scouting he took Doc and other team members on a forty-day trip around the world, paid for by Universal. But that project was put on hold. Doc went on to manage production for The Misfits (1961), Freud (1962), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). On the latter two films, Elizabeth Taylor lobbied for Montgomery Clift—winning on Freud, losing on Reflections. (Brando got the part.)

Knowing my interests, Doc pointed out some of Huston’s directorial touches, including some striking uses of deep space. In the image above, Montgomery Clift’s quarrel with the rodeo judge is framed in the car window while Marilyn Monroe frets that he could have died in his fall from the bull. Doc also thinks that Huston showed adroit staging in the Reflections scene showing Brian Keith wiping lipstick off his mouth while Elizabeth Taylor, in the back seat, uses the rearview mirror to help her repaint her lips.

The movie industry was pushing toward ever more spectacular projects, and Doc sometimes went epic. After a production manager on 55 Days at Peking (1963) quit, the film’s editor, Robert Lawrence, suggested Doc. The film’s direction was credited to Nicholas Ray, but the bulk of the footage was shot by Andrew Marton. There followed Doc’s stint on The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). He recalls Anthony Mann’s excellent eye for composition. The most tangled production was Cleopatra (1963), which had begun shooting in 1960 and was plagued with constant delays. Doc was there for the last eight months of shooting, up to August 1962. He worked under Lewis Merman, the Fox production manager (“one of the greatest human beings I’ve ever known”). Merman was also known as Doc, so the production had both a Big Doc and a Little Doc. It needed even more docs.

Hitch

For my current research I asked Doc a lot about 1940s studio practices, but I couldn’t avoid touching on what everybody asks him about. How was working with Hitchcock? Hitchcock productions have been chronicled in detail by many writers, so I’ll just pick some bits that Doc brought out for me.

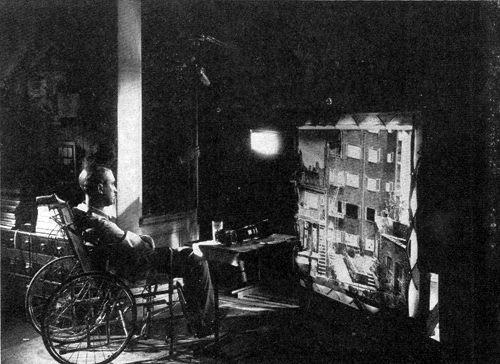

On Rear Window (1954), Doc’s expertise in squeezing sets into a sound stage came in handy. The script demanded that the camera be confined to Scottie’s apartment and that we see only what could be seen from that room. Remarkably, Doc recalls no matte shots being used on the production. The apartment, the courtyard outside, and the apartment building opposite were all installed on a single stage.

Doc was struck by the lighting limitations of this complex and confined set. The color film stock was quite slow, and so illumination levels were very high. He told Douglas Bell:

We had to pour so much light into those apartments, up where Raymond Burr was, it almost put him on fire. It was terrible. Or you would never be able to see him, from where we were shooting. . . . But today it would be nothing, it would be a cinch.

Lens length was also a problem because the camera couldn’t easily simulate the telephoto view of the apartment across the courtyard. Doc found a way to mount the camera outside the window to get a little closer to the opposite building and suggest the enlargement provided by Scottie’s long lens.

Hitchcock had claimed he would need only twenty-four days to shoot Rear Window, but it ran to thirty-six, and its cost was considerably beyond what he had estimated. So great was Hitchcock’s standing in the industry that Paramount didn’t object, knowing the result would be a major picture. Doc was on the set every day. Hitchcock would position the actors and frame the shot, but then return to his chair to watch.

Hitchcock liked Doc and picked him again for To Catch a Thief (1955). For this they left the studio and shot on the Riviera for several weeks—Doc’s first location shoot. After the on-site filming was finished, Hitchcock returned to Paramount for studio scenes and Doc stayed to oversee helicopter shots of the roadways with special-effects specialist Wallace Kelly. The team followed the famous Hitchcock lists and storyboards for such second-unit footage.

Without a break Hitchcock drafted Doc for The Trouble with Harry (1956). Originally to be set in England, the story was transposed to New England. Despite some location work, there were a surprising number of studio exteriors (as are quite obvious to our eyes today). Doc supervised the building of woods on Stage 14, but then scattered around leaves brought in from Vermont and New Hampshire.

Doc was involved in scouting locations in Marrakech and London for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), along with assisting Coleman and Hitchcock in the usual way. Hitchcock clashed with John Michael Hayes on the project, and according to Doc, Steven Derosa’s account of the contretemps in Writing with Hitchcock does justice to the complexity of the situation.

Doc’s memories of the master’s next production, Vertigo, are detailed, but they and other participants’ accounts are chronicled in Dan Auiler’s Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic. What I found surprising were two of Doc’s responses to the project. Doc found that the production went very easily. He thinks that was because he had learned so much about location shooting with the overseas demands of To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much. My second surprise: “We had no sense that Vertigo was special.”

I’m out of step with the world’s critical consensus. I wouldn’t consider Vertigo the best film of all time, or even the best film by Hitchcock. (My votes would go to Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho. All seem to me perfect, endlessly exhilarating pictures.) To a great extent, I think that American Hitchcock never stopped being a 40s director, so I tend to see Vertigo as an uneven mix of plot elements and visual ideas from that wild era. Good as the film is, I think, the expository scenes are rather flatly filmed and lack the flair that Hitchcock brought to such scenes in his earlier films.

But thanks to the undeniable brilliance of many other scenes, along with the revolution of taste promoted by the Cahiers du cinéma critics and the long suppression of the film (making it a sought-after treasure), Vertigo has become a holy grail of obsessional cinema. Its plot premise has fed cinephiles’ fantasies. In the history of taste, a fairly creaky tale of murderous deception has become the ultimate vessel of filmic fascination. One hero’s delusion now epitomizes all movie-made illusion.

Give Doc the last word: “When we finished Vertigo, we never thought of it as being the film that everybody thinks it is today. It’s become bigger than life itself.”

Thanks to Doc Erickson for affable and informative conversations.

Being mostly interested in the Old Hollywood, Kristin and I didn’t question Doc about his work of more recent decades. Those activities are covered in Douglas Bell’s extensive interview, recorded in An Oral History with C. O. Erickson (Los Angeles: Academy of Motion Picture Arts, Margaret Herrick Library, 2006). I’ve drawn much information from this volume. I thank Jenny Romero, Special Collections Department Coordinator at the Herrick Library, for facilitating access to it, and to Kristin for examining it for me during her recent visits to Los Angeles.

For a detailed account of the division of labor on 55 Days at Peking, see Bernard Eisenschitz, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, trans. Tom Milne (Faber, 1993), 378-389. Andrew Marton, who took over the shoot after Nicholas Ray was dismissed, estimated that sixty to sixty-five percent of the finished film was his work. See Andrew Marton Interviewed by Joanne D’Annunzio: A Directors Guild of America Oral History, 413-418.

Herbert Coleman’s book The Hollywood I Knew: A Memoir: 1916-1988, revisits his AD work with Hitchcock in considerable detail, and many of the anecdotes he recounts involve Doc Erickson. For more on the production of Hitchcock’s films, see Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light and Bill Krohn’s Hitchcock at Work.

Without any planning, the last six months or so have been this blog’s Hitchcock period. The entries include items on Dial M for Murder (screened at the Toronto International Film Festival last September), on David O. Selznick, on the first Man Who Knew Too Much, and on the rise of the suspense thriller during the 1940s. On Lumet, for whom Doc also worked, you can see this entry. The production photographs in today’s entry are taken from Arthur S. Gavin, “Rear Window,” American Cinematographer 35, 2 (February 1954), 76-78.

Kristin and Doc Erickson, Ebertfest 2009.