Archive for the 'Film technique: Staging' Category

Not-quite-lost shadows

I.N.R.I.: The Catastrophe of the People (1920).

DB here:

One way to write the history of film as an art is to chart firsts. When was the first close-up, the first moving camera, the first use of cutting? Asking such questions was a common strategy of the earliest film historians, and it has persisted to this day in pop histories. Civilian readers can be excused for thinking that Griffith invented the close-up and Welles originated ceilings on sets. These myths have been recycled for decades.

The “revisionist” historians of the 1970s, mostly academics who aimed to do primary research, pointed out that talking about first times is risky. Too often the official account is wrong, and earlier instances can be found. In most cases, we can’t really know about first times. Too many films have vanished, and nobody can see everything that has survived. Innovation is always worth studying, but, the revisionists argued, it’s best understood within a context.

So they set themselves to figuring out not when certain cinematic techniques began but when they became common practice–when most filmmakers in a given time or place adopted them. That way we can discover innovations more reliably; they’ll stand out against the background of more orthodox choices. But of course, to build up a sense of these norms, it’s not enough to focus on the masterpieces cited in the official histories. You need bulk viewing.

Studying norms of storytelling and visual style is a large part of what Kristin and I have done since the 1970s. One section of our 1985 book The Classical Hollywood Cinema tried to chart when certain fundamental techniques of Hollywood storytelling coalesced into common practice. Kristin argued that the late 1910s are the key years, with 1917 as a plausible tipping point. By then, continuity editing and goal-oriented plotting, among other creative options, became dominant practices in American features. If you’re interested in blog posts touching on this, see the codicil.

Yet it’s reasonable to ask: But what happened in other countries? Was Hollywood unique, or were there comparable norms emerging in Russia, France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and elsewhere?

Several years ago, I began trying to watch as many US and overseas features from the period 1908-1920 just to see what I might find. Doing this led me to make arguments about the development of staging-driven cinema (often, but not only, European), as opposed to editing-driven cinema (usually, but not invariably, American).

A vast resource for my bulk viewing of 1910s cinema has been the Royal Film Archive here in Brussels. While the collection houses virtually every classic, it also includes films that haven’t been discussed by many historians–obscurities, if not downright rarities. Films from many countries passed through Brussels, and the archive was able to acquire copies from many distributors going back to the 1910s. Although I had watched several German films in the collection on earlier visits, this year I had a pretty concentrated dose. So as in previous years (see that codicil again), I offer you some chips from the workbench.

Cinematic scarcity

I.N.R.I.

German films of this period are of special interest for my research questions because of an unusual situation. From 1916, films from the US and nearly all of Europe were banned from Germany, and this ban held good until 31 December 1920. As Kristin puts it in her book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available as a pdf here):

Foreign films appeared only gradually on the German market. In 1921, German cinema emerged from years of artificially created isolation. . . .Because of the ban on imports, German filmmakers had missed the crucial period when Hollywood’s film style was changing rapidly and becoming standard practice. . . . The continuity editing system, with its efficient methods of laying out a clear space for the action, had already been formulated by 1917. The three-point system of lighting was also taking shape. In contrast, German film style had developed relatively little during this era.

Kristin was again exploring craft norms, the creative choices favored by Lubitsch’s contemporaries. She drew some of her evidence from films she saw here at the Cinematheque, but I wanted to revisit those and see some others. What exactly did German films look like at this point? Not the official classics like Caligari and Nosferatu, but more ordinary, maybe even bad movies?

The basic assumption: Since the German directors weren’t seeing American movies, they’d be less likely to imitate them. Some hypotheses follow from this. German directors would presumably rely less on cutting, especially within scenes, than Americans did. They might incline toward staging complicated action in a single shot. The cutting is likely to be what Kristin calls “rough continuity” or “proto-continuity”–essentially, long shots of the whole action broken by occasional axial cuts that enlarge something for emphasis. We wouldn’t expect to find sustained passages of close-up or medium-shot framings.

To give myself some reference points, on each visit I’ve watched European films in conjunction with American films of the same era. This mental trick helped differences pop out more easily.

Fortunately for peace in our household, I’ve found Kristin’s claims about German cinema well-founded. As in other years, I also stumbled across some gratifyingly strange movies.

Blocking, tackled

Throughout the period 1908-1920, we find many scenes staged in a single fixed shot. In many other blog entries, and in books like On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I’ve tried to show that this wasn’t simply a passive recording of a “theatrical” scene. Drawing on capacities specific to the film medium, directors used composition, lighting, setting, and figure movement to shape the perceptual and emotional flow of the scene.

Here’s a late example from The Brothers Karamazov (1920) directed by Carl Froelich and Dmitri Buchowetzki. Starring Fritz Kortner, Emil Jannings, Werner Krauss, and other heavyweights, it has perhaps more ham per square inch than any other film I saw on this pass. Yet its tableau moments subordinate the performers’ charisma to an overall expressive dynamic.

Old Fyodor Karamazov has been murdered, and his son Dmitri is accused of the crime. Protesting his innocence, he’s about to be arrested when Grushenka bursts out. “I’m the guilty one!”

In the tableau tradition, “blocking” takes on a double meaning–not only arranging actors in the shot, but also judiciously using them to mask or reveal areas of space. Thus Dmitri at first blocks Grushenka, but when he lowers his hands, she pops into visibility–frontal and centered, so we can’t miss her. Dmitri sinks to the lower half of the shot when her dialogue title comes up, leaving her to command the frame. Meanwhile the police official has pivoted slightly, making sure that we pay attention to her outburst. Not incidentally, he blocks another policeman behind him, keeping the frame dominated by Grushenka.

This scene goes on quite a bit longer, with some careful balancing and rebalancing of points of interest in the lower part of the frame. The action ends with a nice touch: the embracing Dmitri and Grushenka are separated, and she’s pulled away, one arm flailing.

Without benefit of cutting, then, techniques of tableau construction guide our attention smoothly in the frame by using movement, centering, advance to the camera, character looks, blocking and revealing, and other tactics.

The Germans had embraced this tableau option in the earliest 1910s. The films of Franz Hofer and others show how an entire scene could be covered in a single camera position, with staging providing a continuous flow of interest. Go here for an amusing example from The Boss of the Firm, a 1914 comedy starring Lubitsch.

The commitment persisted into later years. The earliest film I watched in this cycle, Hilde Warren and Death (1917), by the quite interesting director Joe May, had several passages of tableau staging. In the most elaborate one, the mistress of Hilde’s dissolute son tells him that now he’s out of money, she has switched her affections to a rival. It plays out without a cut or intertitle for about a minute at 18 frames per second. When Fernande spurns him, he grovels, just as the salon door opens. (Whenever there’s a rear door like this, we’re likely to get a tableau scene.) His rival shows up to take her to the opera.

Fernande asks him to stay outside, but the son demands that he stay, waving his hand. In a staging tactic that should be familiar to us now, the son rises, blocking the rival for an instant.

The rival rebalances the composition, and makes himself visible, by moving to the right background. This switching of characters’ position in the frame is known as the Cross. But when the son gets angry, the rival crosses again, easing himself toward the area of conflict. Note that the son’s bodily attitude, tensing up, actually shifts him rightward a little, opening up a space for the other actor to be seen.

Now the rival steps to the forefront and wedges himself in between Fernande and the son. He invites the young man to leave, with a gesture that occupies the dead center of the frame: Who could miss its assured insolence? And now the maid, previously in the background and blocked by Fernande, makes herself known. Seeing how things are developing, she fetches the son’s hat.

The son gets off one last grimace, front and center, before departing. As he walks back, the rival swivels to blot him out, leading the ladies in mocking laughter. (It’s clear the rival belongs to the 1%.)

One good Cross deserves another: Now the rival settles in where the son was at the start of the scene, and the son is retreating in shame along the rival’s path.

This tableau technique, constantly calculating points of interest from the standpoint of monocular projection–that is, what the camera lens takes in–is far from theatrical. Well-timed blocking and revealing wouldn’t work given the multiple sightlines of a theatre stage. The action is staged for the only eye that matters: the camera’s.

Once we grant that theatrical playing space is quite different from that provided by the camera, we can see more exactly what the tableau tradition owes to the stage. Silent cinema’s “precision staging,” as Yuri Tsivian has called it, is close to choreography. If we want to appreciate what directors of this period accomplished we need to look at the scenes as varieties of pictorialized dance, designed around the axis of the camera lens.

Along the lens axis

To return to the first question: Yes, German films seem to have clung to the tableau tradition after 1917, when Americans had abandoned it. Yet shots like those in The Brothers Karamazov and Hilde Warren are fairly rare; most scenes in most German films of the period use a fair amount of editing. What do we make of that?

The trend is fairly general. Some staging-driven films, like Ingeborg Holm (1913) and the early serials of Feuillade, are built entirely out of one setup per scene, occasionally broken by cut-ins of printed matter or other details. This period constituted a brief golden age of this “tableau” tradition–visible in American cinema, but more pervasive in European cinema. But by the late 1910s, most directors around the world were cutting up their dialogue scenes at least a little. Gradually, the tight choreography of the tableau gave way to the easier method of using close-ups to pick out key instants.

The European default seems to have been what Americans called the “scene-insert” method. A long shot (called the “scene”) is interrupted by a cut to some part of it (the “insert”). Then we go back to the orienting view. The cuts are typically straight in and back along the lens axis.

Here’s a straightforward German example from The Devil’s Marionettes (Marionetten des Teufels, 1920). A fake medium has been brought to a rich man’s home to read the fortune of his daughter. As she leaves he pays her, and from his ring she’s able to identify him as a Duke.

Note that the first setup is much farther back than the tableau scenes in Brothers Karamazov and Hilde Warren. There’s not much to be done with such a distant shot except cut in.

The Devil’s Marionettes scene has two inserts, but it’s conservative by American standards. By 1917, Hollywood directors were increasing the number of “inserts” considerably and making them the dominant source of the ongoing action. Some European directors took this option; notable instances are Abel Gance and Victor Sjöström. Others, though, relied on the scene-insert approach, not building the action out of a lot of closer views. The post-1917 German films I’ve seen, most recently and on other occasions, favor a moderate scene-insert approach like the one in Marionettes. Accordingly, the “pure” tableau option waned.

Yet one basic idea of the tableau strategy persisted. We can see this in directors’ use of the axial cut, which provides a constant orientation to the setting. While American directors were often building up a scene from many angles, German directors seemed reluctant to show the action, at least in interior sets, from distinctly varied viewpoints. So when they broke a dialogue scene into many shots, they stuck to the camera axis, cutting in and out along that. You can see that in the Marionettes scene. Consider as well this moment in I.N.R.I.: The Catastrophe of the People (1920). Within a single overall orientation, the editing enlarges or de-enlarges the three characters in the boudoir.

Even with the drastic enlargement from the first shot to the second, or from the third to the fourth, our orientation is basically the same. The staging cooperates with this strategy, making sure that all three players’ faces turn to the camera, even if their bodies are angled away from it. They’re playing to the lens axis, we might say.

When directors try to shift the angle more drastically, the consequences can be strange. In Rose Bernd (1919), an adaptation of a famous Gerhardt Hauptmann play, an axial cut has brought the bullying Streckmann striding toward the camera to meet his wife and Rose, chatting in his garden.

As he flirts with Rose, director Alfred Halm provides another axial cut, from farther back, as a neighbor woman passes in the foreground. Rose turns to look.

The print is missing dialogue titles, but there evidently was one here, as Rose comments on the woman passing. The dialogue title provides some cover for the extraordinary cut to the next shot.

The time is clearly continuous, as the woman is still walking past the garden gate, now in the distance. But Rose, Streckmann, and his wife have been completely rearranged in the frame. They’re positioned frontally, as in the I.N.R.I. boudoir example, and they create the sort of foreground/ background dynamic characteristic of 1910s cinema generally. Halm could have shown Rose’s comment and the others’ reaction by cutting back in along the axis, to a closer shot of the group in the garden (like the second one above). Instead, he shifted his camera position sharply. The new shot does highlight Rose and her gesture, but at the price of spatial coherence.

Aliens, missing shadows, and lustful monks

Tötet nicht Mehr!: Misericordia (To Kill No More!: Misericordia, 1919).

So some of our hypotheses seem borne out. Many German directors apparently adopted a conservative position toward American-style analytical editing until the ban relaxed in 1921. After that, as Kristin documents in her Lubitsch book, films by Murnau, Lang, and others employ more varied angles and less frontal staging. It seems likely that the Germans learned about this approach from the new availability of films from America and European countries (some of which were adopting the American approach).

My latest plunge into Weimar cinema yielded other enjoyments. It’s commonly said, for instance, that Germans experimented with expressive lighting effects. So did directors in many other countries, but I did find some striking uses of sparse, stark illumination. One example is the prison cell from Tötet nicht Mehr!: Misericordia (1919), above. Even more daring is this double close-up from I.N.R.I.

Harvey Dent has nothing on the conniving Russian student Alexei, half of whose face seems just scooped away by shadow. The faint shadow cast on the wall tempts us, in a weird Gestalt illusion, to see his head as partly transparent.

Another area of German expertise was special effects, and I saw plenty of sophisticated double exposures, matte shots, and split-screen tricks. As you’d expect, some of these were used to suggest hallucinations or the supernatural. At the very top of today’s entry is another image from I.N.R.I., which presents the student Dmitri’s fever dream. Below are a couple of nice ones from Lost Shadows (Verlorene Schatten, 1921). A Satanic traveling showman puts on shadow plays, but his cast is drawn from real life: He bargains with people for their shadows, and eventually leaves the hero without one.

What, finally, about what we all yearn for: an extravagantly nutty film? Nothing in this foray matches the work of Robert Reinert (Opium, Nerven), about which I’ve written in Poetics of Cinema and on the DVD restoration of Nerven. Reinert is on another plane of delirium, as mentioned in an earlier entry. Nonetheless, apart from moments in many of those movies already discussed, I found two pervasively peculiar items.

The more well-known is Algol (1920), directed by Hans Werckmeister. The sets, although designed by Walter Reimann of Caligari fame, aren’t cramped and contorted but are instead vast, geometrical, and a bit reminiscent of the Monster-Machine aesthetic of Expressionist theatre.

The plot is your everyday visit from another planet. An alien from Algol visits a coal mine and gives a loutish miner a machine that generates endless energy. (Today the Algolian could take a bribe from an oil company to head back home.) The miner becomes a tycoon controlling the world’s energy supply. This monumental fantasy (big sets, big crowds) is enacted with maniacal gusto by Emil Jannings, who spends his wealth, like all good plutocrats, on bacchanals featuring crazy dancing.

Algol is forthcoming in the Filmmuseum DVD series.

The Plague in Florence (Die Pest in Florenz, 1919) is less famous, although the script is by Fritz Lang. Directed by Otto Rippert (Homunculus, 1916; Totentanz, 1919), this tells of Julia, a woman whose all-powerful sexuality wreaks havoc on the city. Even churchmen lust for her, and eventually Florence sinks into debauchery. What redeems, if that’s the right word, the city is the appearance of a plague that strikes citizens dead in their tracks. Personified as a gaunt woman rising up from the marshes and mournfully playing a violin, the plague eventually kills Julia and her umpteenth lover.

Before this, we’ve had everything I’ve mentioned and more: a couple of fancy tableau sequences, axial cuts, wild mismatches between shots, spectacular lighting effects (e.g., catacombs, below), and hallucinatory sequences. At one point, the mad monk vouchsafes Julia a glimpse of the horrors to come by showing her a river of corpses calmly flowing underground.

Of course the monk isn’t invulnerable to Julia’s charms. Trying to pray away the impulses she arouses in him, he sees her as his Savior. Herr Rippert, Señor Buñuel is on the other line.

Who knew film history could be so surprising? You don’t get this stuff in your usual pop history. But maybe it’s better we don’t share this with the civilians.

My usual heartfelt thanks to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, its staff (particularly Francis, Bruno, and Vico), and especially its Director, Nicola Mazzanti. Thanks also to Sabine Gross for a translation.

My previous Brussels research visits are chronicled in this blog over the years. A 2007 entry talks about my viewing method and concentrates on Yevgenii Bauer. The following year’s entry is devoted to William S. Hart. An eclectic 2009 one surveys films from Germany, France, Denmark, and even Belgium. In 2010 I went twice, once in January (watching mostly Italian diva films) and as usual in July (but no entry for that visit, consumed as I was with writing about Tintin). The 2011 entry is diverse, covering many national cinemas, and, implausibly, runs even longer than the others.

We have many other entries on film style in the 1910s. One considers how the Hollywood style coalesced in 1917; another talks about Doug Fairbanks. There’s also an entry on 1913, which discusses both Suspense and Ingeborg Holm, and there are discussions of Sjostrom as a master of both the tableau approach and continuity editing. And of course there’s plenty on Feuillade’s staging; you might start here, and perhaps pause over the mini-essay here, which talks about the director’s eventual experiments with editing. Elsewhere on the site there’s an essay on Danish cinema that echoes some points made in today’s entry. (Unlike other countries, neutral Denmark was able to send its films to Germany during the war, so there may have been some influence there.) Broader comparative arguments about this material have been sketched in a lecture I’ve given in various places, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Interest in German cinema of the period grew after Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto held its trailblazing program published as Before Caligari, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (University of Wisconsin Press, 1991; now, alas, very rare). See also the valuable collection edited by Thomas Elsaesser, A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades (Amsterdam University Press, 1996). Kristin has an essay here on Die Landstrasse (1913), a remarkable instance of the tableau style.

As my research on the 1910s draws to a close, I’m thinking of how to synthesize and present my arguments. Originally I was considering a book, but the number of stills, and the specialized nature of the project, would probably make publishers shudder. At the moment, I’m thinking about creating a series of PowerPoint lectures, with voice-over. These would be freely available for people to use in courses if they wanted. That initiative would be another experiment in using the Web to get information and ideas out there to interested readers.

Professor Bordwell illustrates his views on visual storytelling (Algol).

Talks, pictures, and more

Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege, which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours, called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun (cont’d)

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course, “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen and the now-departed Capital City comics distribution firm. (DB)

Le mot Joost

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here and here and here); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is?

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here and here, in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist, a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation.

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here.

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here.

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.

Hand jive

The Magnificent Seven.

DB here:

In the long trailer for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Rooney Mara as Lisbeth Salander makes a gesture to show that her fabulous memory has recorded the documents Blomkvist wants her to read over. She raises her hand toward her head and flicks her spindly forefinger.

It reminded me of how important gestures are to film performances, and how comparatively rare they are today. One feature of what I’ve called the contemporary intensified continuity style is a reliance on tight facial shots, so that actors work more with their eyes, eyebrows, and mouths than with other body parts. This solves one perennial problem actors have: What do I do with my hands? But it does cut off a lot of expressive possibilities. When filmmakers used more medium and long shots, actors could use all their equipment—stance, bearing, knees (as in The Cary Grant Crouch), elbows (The Cagney Cocked Elbows), shoulders. And arms, and hands. Nowadays if actors want to activate their hands in a dialogue, they usually have to lift them to their faces because the director hasn’t provided a looser, more distant framing.

I’ve already shared some thoughts on eyes (and argued that they aren’t as expressive as we usually think), eyeblinks, and sleeves. I’ve written about hands before, and Tim Smith has tested some of the things I discussed. Now I’d like to write about two of the best hands in the business. Before I do, though, let’s look at some simpler cases.

Handiwork

Rooney/Salander’s finger flip is a one-off, a staccato gesture that communicates instantly. It reminds us that she is, for all her cybernetic genius, rather nonverbal. Her dialogue is laconic, her face impassive. The gesture comes and goes like a keystroke. If there are air-quotes, this is an air-period.

Something more emphatic happens in Wuthering Heights, as you’d expect from (a) the more extroverted emotion of the tale and (b) the fact that the owner of the hand is matinee idol and occasional ham Laurence Olivier. Early in the film, Lockwood is staying the night in Heathcliff’s dismal mansion. He tries to close a shutter, and finds the windowpane already broken. He’s startled by what he hears (“Heathcliff! It’s Cathy!”) in the stormy night. He also thinks he sees a phantom woman. Unnerved, he pulls his hand back through the pane and stares at his trembling fingers.

This occurs in the frame story. Later that evening Lockwood is told of the tragic romance of Heathcliff and Cathy, and we get an extended flashback. Cathy yearns to join the high-flown elite in the neighborhood and is about to go out with Edgar Linton. In her petulance Cathy calls Heathcliff a stable boy and a beggar with dirty hands. Heathcliff stares down at those hands (“That’s all I’ve become to you, a pair of dirty hands”), before he slaps Cathy with one, then the other, crying, “Well, have them, then—have them where they belong!”

He stumbles from the room in a mixture of anger, shame, and confusion. Coming down the stairs he confronts Linton, who has just arrived to pick up Cathy for the party. Heathcliff stands awkwardly on the stair, his hand held at an angle, as if it’s something he’d like to slough off.

Back in his stable loft, Heathcliff smashes his fists through a window, in the manner of the broken pane that Lockwood will discover in the frame story.

Later Heathcliff, now wealthy, returns to the neighborhood. When he visits Cathy, who’s now married to Linton, he initially hesitates to shake hands with his old rival. It’s a beat long enough to remind us of the class difference marked in a pair of hands.

For a more unstressed example, consider The Magnificent Seven. Throughout the movie Steve McQueen invents hand business with the apparent aim of stealing every shot he’s in. At the very start, poor Yul Brynner is trying to be the brooding main attraction, ominously lighting a cigar. But Steve is making us watch him by shaking shotgun shells against his ear and then holding his hat up against the sun.

Soon afterward Steve sets a whisky bottle precariously on a fence post while Yul is acting seriously serious. Then McQueen has the nerve to fiddle with his hat so that Yul can no longer ignore him.

Much later Steve faces down Calvera’s outlaw band and strides into the foreground, back to us.

In such a setup, the actor who turns away is traditionally ceding the audience’s attention to the frontal players in the distance. Not Steve. Once he gets into place, he swivels just a bit and swings his hand behind his gun belt. (That instant surmounts this entry.) Then he tucks one finger in his hip pocket in the lower right corner of the shot.

If Tim Smith ran an eye-scanning experiment on this shot, my hunch is that a fair number of his subjects would watch Steve’s digits.

Hands down

McQueen’s scene-grabbing reminds us that once a filmmaker has framed the performer from fairly far back, judicious use of the hands can activate areas of the frame we normally don’t watch. After all, in most shots the upper half carries the most information, especially with respect to the actors’ bodies. My favorite example of highlighting a lower corner remains a shot from Kriemhilde’s Revenge (above). The director, Fritz Lang, laid out his frames with the precision of an engineer.

Even in a less exactly composed shot, slight hand movements down the frame can add gradation of emphasis. Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman presents some hard-boiled poker players forced to listen to a radio song that interrupts their game. They sit still, but their fingers stir a little, suggesting their impatience to get on with playing.

Now we’re moving into the area I described earlier this fall as scenic density. Several of my examples there involve small gestures. To take another instance, here’s Mercedes McCambridge in her Oscar-winning performance in Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men. As tough campaign strategist Sadie Burke, she’s trying to explain to Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) that he’s running as a dummy candidate for the very men he opposed at the start of his political career. (The whole movie will remind any Wisconsiner of what our Governor and his pals have been up to lately.) The scene pivots around drinking, and the saliency of Sadie’s hands is heightened by the fact that the men’s hands aren’t used at all.

After she pours herself a drink, Sadie tells Willie he’s been framed, holding her glass at her waist.

She walks away to the right, then turns and says that Willie is “the goat.” She sets her glass down at the far right of the shot.

She steps toward him and leans on the chair, tipping forward.

Jack Burden (John Ireland) steps to center frame and says that’s enough. But she presses in on Willie, saying his egotism has made him blind. There’s a cut to a tighter framing as Sadie faces Willie in profile.

She turns away, mocking Willie, and yanks the speech out of Jack’s typewriter.

She steps left to the foreground and pauses, momentarily abashed by her attack on the man she loves. Her hands do something below the frame line.

Stepping back and turning away from us, she lets us concentrate on Willie. He quietly asks Jack, “Is it true?” As Sadie shifts her position, she raises her arm and we see she’s pouring another drink.

Jack replies after a pause: “That’s what they tell me.” As Willie hangs his head, Sadie’s hand emerges at the bottom of the shot to offer him the drink she’s poured. A more assertive director would have cut to a big close-up of Willie and the proffered glass, but here the information slides into a rarely used area of the frame. The Kriemhilde trick, we might call it.

Willie takes it, and Rossen cuts to a low angle on all three, with Jack and Sadie watching the key gesture: Willie, a teetotaler, downs the drink.

Now the only hand visible is his, and the narrative momentum has passed to him. He’ll change his tactics and crush his handlers.

I can’t resist a more recent example of a similar strategy. In Mysteries of Lisbon, Raúl Ruiz keeps fairly far back from his players, filming many scenes in a single distant shot. Even when he breaks the scene into shot/ reverse-shot, he can isolate gestures in the full frame in ways that echo the handwork in Kazan (and in the work of other directors, particularly in the 1910s). Elisa de Monfort, quietly mad with vengeance, calls on Eugénia, the wife of her hate/love object Alberto de Magalhães. In the opening setup, Elisa sweeps in to wait for Eugénia, setting a purse on a distant end table. (The action is quite marked on the big screen, but might be missed on video; this is the price the modern director pays for using long-shots, I guess.)

At the end of the conversation, Ruiz cuts back to the main set-up. Because of Eugénia’s position, the purse nestles in the sort of slot that we find at the bottom of the frame in All the King’s Men above. Elisa rises and goes to pick it up, her gesture highlighting it.

It contains the eighty thousand francs she is trying to return to Alberto, a love pledge he has been refusing. Elisa picks it up, then drops it back to the table, defiantly leaving it for him.

By now I’d again bet that Tim Smith would find our eyes fastened on this tiny bit of the screen. Hands point us to props, and close-ups may not be necessary.

All hands on deck

I’ve praised Henry Fonda’s handicraft earlier on this site (and in Film Art: An Introduction). Maureen O’Hara said of him: “All he had to do was wag his little finger and he could steal a scene from anybody.” But to see his long fingers and fluid wrists at full stretch, put him in a combo. There’s a remarkable six-minute scene in Mister Roberts that lets Fonda (playing Roberts), William Powell (as the ship’s doctor), and Jack Lemmon (as Ensign Pulver) make beautiful music. I can’t go through it all, but let me mention some high notes.

Roberts wants to give the crew a day’s liberty, and to that end he’s bribed a port officer with a bottle of whisky he’s been saving. But Pulver, a lecherous layabout, has convinced a nurse to come to the cabin he shares with Roberts, and he’d planned to seduce her with the Scotch. So to help Pulver out, Roberts and Doc will concoct fake Scotch with ingredients they have at hand.

As I work it out, Powell supplies gravitas, a steady ground bass of minimal, exact gestures. Lemmon, playing Pulver as wound much too tight, punctuates his passive role with nervous head movements and stabbing arms. He supplies percussive accents. Fonda’s relaxed but severe playing, neither stolid nor spiky, is the melody that floats through it all.

At the start, after the older men have entered, Pulver is slouching, Doc is wiping off sweat, and Roberts is looking for his monthly letter requesting transfer.

As Doc replaces his hat, Roberts stresses his explanation about the whisky with a quietly tapping forefinger, a gesture you can hear on the soundtrack.

When Pulver realizes that the sacred bottle is gone, he jolts into activity, frantically pointing, as if in amplified imitation of Roberts.

Throughout the scene, Pulver will echo Roberts’ gestures, as when the senior officer lays his arm across his belly.

This mirror-effect is tied to the larger dramatic dynamic: Pulver looks up to Roberts, but his selfishness keeps him from being anything like his model. In the film’s last scene, however, he will become the new Roberts.

As Roberts and Doc decide to help Pulver, they give virtually silent-film renditions of the concept, “planning and preparing.” Powell roles up his sleeves, and Roberts claps his hands and then rubs them together as if hatching a plot. Hand-rubbing will be his refrain through the rest of the scene.

No actors under age fifty today, I think, would dare this sort of straightforward stylization. Here’s something to do with your hands, cast members.

When Doc requests a Coke to add to their ethyl alcohol, Pulver yanks a bottle out from his mattress and thrusts it across the CinemaScope frame.

Doc adds the Coke with surgical precision. All eyes are on his hands, while Roberts’ hands are out of frame.

Pulver is still skeptical and sits back down on his bunk. The dramatic impetus passes to Fonda, whose long forefinger rests meditatively under his nose: Thinking personified.

Fonda has to shift his hand in order to remark that Scotch has always reminded him of iodine. But what other actor would rotate his wrist and stick his thumb under his eye as he says that line? Try it yourself, and I bet you find it awkward. He executes it smoothly.

Without having to get up, Roberts reaches back into the medicine chest and pulls down a bottle of iodine. He passes it to Doc and signals the handoff with a little flourish.

Earlier we’ve seen Doc do the mixing as a solo performer, in the over-the-shoulder shot shown above. As Doc blended the stuff in other framings, Fonda kept his hands below the desk top, giving Powell the stage. But now we get two for the price of one: Powell’s meticulous adding of a drop of iodine to the brew, Fonda’s revisiting his calculating hand-rubs.

Fonda’s slightly out-thrust tongue is a grace note.

Pulver tries to sample the blend, but Doc beats him to it. “We’re on the right track!” he declares. Doc asks Roberts what else he’s got and Fonda, in a beautiful medium-shot with eye-catching colored medications arrayed before him, mimes the act of mulling over the next ingredient. His hand flits gracefully over the bottles and jars.

They settle on hair tonic for a touch of ageing. Again Doc adds the ingredient with precise pouring, and now he prepares for Roberts to test it. Into the frame come Fonda’s hands.

To accentuate the climax of the scene, Roberts rises to take the drink, forestalling Pulver.

Roberts clears his palate, then drinks it, pinky extended, as daintily as a lady at a party.

He stares at the glass, swallowing. Then Fonda’s hand lowers out of the frame so as to let us concentrate on his expression. His strangled line tops the whole comic arc: “You know, it does taste a little like Scotch.” Now his face does the work.

All three players are reintegrated into a master shot: patient Doc, frantic Pulver, and stalwart Roberts as they realize they’ve succeeded. Pulver, after lunging with his characteristic abruptness, finishes the glass in a hunched-over gulp.

“Smooth!” he yelps.

You might argue that such hand jive is rather “theatrical,” and perhaps some of the business came from Fonda’s three years in the Doug Roberts role on Broadway. Even so, it has clearly been recalibrated for the cinema. Theatre taught actors how to use their hands, but cinema gave them further lessons, and film directors learned to choreograph hands in relation to framing and shot scale.

My discussion doesn’t exhaust the scene, but I hope it suggestst how choices about staging and performance can make hands carry story information and express character. They can add nuance to a moment; they can surprise us by slipping into and out of visibility; and they can inflect a facial expression or line reading. If filmmakers today lock their framing on facial close-ups and moving lips, they’re depriving us of some beautiful music.

P. S. 18 January 2012 (from Midway, Utah and the Art House Convergence): Thanks to three alert readers. First, Adrian Martin spotted an orthographic error, now corrected. Second, David Cairns of the indispensable Shadowplay) writes of scene-stealing in The Magnificent Seven:

You do know what Yul said to Steve? “If you don’t stop playing with your hat, I’ll take off my hat, and then we’ll see who they’ll look at.”

And from James Benning, with the laconic message: “Here’s another.”

I wrote about Jim’s related project here.

P.P.S, 20 January 2012: This entry’s title, as many readers noted, referenced the great Johnny Otis song “Willie and the Hand Jive.” Today Ethan de Seife writes to tell me that Johnny died the day before my blog was posted. So take it as not only an homage but a valedictory.

Mr. Roberts.

You are my density

DB here:

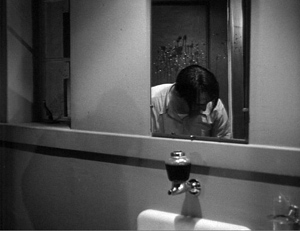

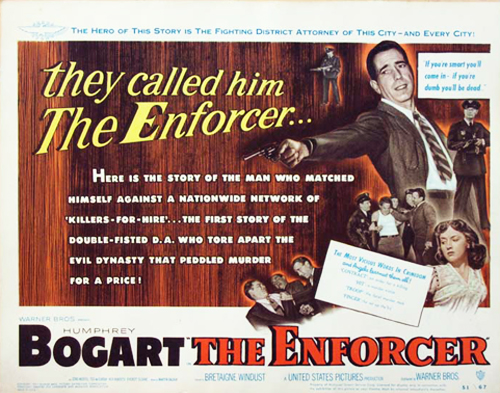

The mobster Joseph Rico is in protective custody; tomorrow he testifies against the big boss. But Rico fears reprisals, so he decides to escape. While a sleepy cop guards him in the washroom, he bends over the sink and rinses his face.

Turning so suddenly that water spatters on the mirror, he grabs the cop in an armlock and slams his head against the sink, just below the frameline.

Rico turns to the window to make his escape.

What interests me in this passage from The Enforcer (1951) is not just what happens in the mirror but also what happens on it. While Rico belabors the cop’s head, we’re given a chance to notice the splash of water that hit the mirror when Rico whirled to the attack. While the action is moving forward, we’re reminded of what had triggered it.

We get a sort of parallel reminder in the next scene, when we see the wounded cop again. He’s sporting a big bruise on his left temple, a souvenir of Rico’s assault.

Pfui. Details, you might say. Or you might (correctly) instance this as another case of Charles Barr’s enlightening notion of gradation of emphasis. But it’s worth getting a little more specific, because even this simple scene (by non-auteur director Bretaigne Windust) offers us something to think about, and something for today’s filmmakers to try.

Most films today don’t fully exploit the visual dimension of cinema. True, we have dazzling CGI and fancy camera moves. But when it comes to less flamboyant scenes, directors have limited their options by relying too much on stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk. There are other aspects of visual storytelling that today’s filmmakers neglect. One aspect is the possibility of gracefully moving actors around the set in a sustained fixed shot. A specific tactic I’ve mentioned before is the Cross, and another involves ways to get people into a room. The option I’m going to sermonize about today is what I’ll call scenic density.

By scenic density I mean an approach to staging, shooting, and cutting in which selected details or areas change their status in the course of the action. I don’t count the bustle of background business, all that street traffic that is so much pictorial excelsior in our movies. Nor do I refer to stuffing the setting with desk and kitchen flotsam, allusive pop-culture posters, and the other distinctive “assets” that will be exploited when the film’s world gets transposed to a videogame. I mean something more expressive and intriguing.

Using it up

Go back to the Enforcer scene. The shot’s composition creates a delimited zone of action. The guard cop is framed tightly in the mirror. When the fight breaks out, it’s initially framed in that mirror–a narrowing of visual importance. Moreover, the shot is designed to highlight the spatter on the mirror. It’s fairly prominent, stuck near the center and, providentially, in the spot that the cop’s head initially occupied. The lighting picks out the drips, and in a shot where the figures move in and out of frame, there isn’t an equally constant center of interest. We’re probably concentrating on Rico’s punishing of the cop, but the dribbles of water remain prominent enough to claim our interest, especially when Rico passes out of frame.

So here’s my first condition for scenic density: the shot keeps several items of dramatic significance salient in the composition.

This technical choice asks the filmmaker to think of the frame as a field of dynamic masses and forces. Such an idea was part of the aesthetic of “advanced” European and Japanese silent cinema of the 1920s. Many directors explored this dynamism, often aided by low angles and wide-angle lenses. Here are examples from Eisenstein’s Old and New and Murnau’s Tartuffe.

This pictorial density became especially prominent in American cinema during the 1940s, when low angles, wide-angle lenses, and locations and smaller sets encouraged cinematographers to pack their compositions snugly, as in this shot from Panic in the Streets.

Boris Kaufman, cinematographer for Jean Vigo and Elia Kazan, summed up the principle:

The space within the frame should be entirely used in the composition.

Since cinema is a time-bound art, however, the salient elements in the shot could and should change. But if the frame space is wholly “used,” what room is there for change? The only options are to have the using-up elements shift position, or to reveal that the frame isn’t used up.

Vivid instances, also from the 1940s, can be seen in Anthony Mann’s work, both with and without John Alton. Generally, Mann used the new fashion for depth composition, especially big foreground elements, to heighten scenes of violence. Physical action becomes more aggressive if people rush the camera and halt in tight close-up, especially because wide-angle lenses tend to accelerate movement to the foreground. Mann thrusts violence abruptly to the camera with an almost comic-book effect, as when the club owner is shot in Railroaded, or a man is flung to the floor in Raw Deal.

Even when this in-your-face tactic isn’t employed, the Mann films find ingenious ways to develop what seem to be completely locked depth compositions. In Border Incident, Ulrich confronts the Mexican government agent Pablo, disguised as a Bracero. A looming depth shot is followed by a reverse shot displaying a compact composition.

Is the frame space fully used? The second shot above is opened up when Ulrich leans forward to sock Pablo, creating a vacant spot on the far right for Pablo to fall into. The shot is emptied and re-filled, dense once more.

Memories, memories

Aha, you may be saying. Density just refers to squinchy, fussy shots from an era that favored cheap flash. No. The Enforcer shot isn’t all that cramped. Of course the blank, unchanging walls serve to highlight the mirror-reflected fight and the water dribbling down the glass, but you can imagine how much more jammed and skewed Mann’s treatment of Rico’s escape would be. As for the flashier depth, I just needed some clear-cut cases of density, examples in which details and spatial zones become starkly salient. Now I want to suggest that scenic density can be achieved in something more spacious, even monumental. That has to do with time and memory.

Part of what gives the Enforcer shot its interest is the superimposition of two moments of action in a single space: Rico’s diversionary turn from the washstand, recorded in the splash he made on the mirror, and the struggle taking place a few seconds later. A further trace of that struggle and that splash is visible in the bruise on the cop’s head in the next scene.

That dripping spatter can stand in for the second quality of spatial density I want to highlight: Its capacity to coax us to recall earlier action in the locale. Characters leave their marks and spoors in the space, and those get activated as memories. Unlike the slick surfaces of today’s settings, in classic films the settings can bear the impress of human transit, leading us to recall bits of behavior and emotional states. Let me illustrate from Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

It’s Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, and Gestapo Inspector Ritter is questioning Mrs. Dvorak, the vegetable seller who could identify the woman who misled the officers pursuing an assassin. Torture, or at least what we think of as torture, hasn’t started. She is simply standing in front of his desk as he brandishes his riding crop in the manner of a good movie Nazi.

When Mrs. Dvorak denies knowing the woman, Ritter taps the back-rest of the chair. It simply falls off, and we realize it’s not fastened to the chair.

Ritter says, “Pick it up again.” Now we realize that intimidation has been applied for some while; Ritter has made the woman stoop to replace the back-rest many times. She does so again as the camera tracks back. This is nicely detailed too. She starts to pick it up by bending over, finds the effort too painful, and then goes to her knees to pick it up–just as Ritter taps his riding crop against her hand, a teacher gently chiding a slow pupil.

As Mrs. Dvorak rises to put the piece back in place, the camera pans slightly right to pick up the woman bringing in a tray. Happily Ritter sniffs the coffee jug and resumes questioning the old woman.

Cut to a shot of her by the chair. “Let’s start from the beginning,” says Ritter, offscreen. Unthinkingly Mrs Dvorak starts to rest her hand on the loose slat, forgetting that the top slat is unattached. It’s a natural response. She’s been standing there for a long time and would like something to rest on, and the chair is temptingly close. (Presumably, that’s its purpose, to taunt the unwary prisoner forced to stand a long time.) Remembering just in time, she yanks her hand away. If she knocks the back-rest off, she’ll just have to pick it up again.

Cut to Ritter. “Don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak. I’m prepared to—”

Cut to Mrs. Dvorak. As he continues, “–devote to you all of tonight,” she forgets herself again and relaxes her hand, this time on the back-rest. It falls off, making her start.

She looks up as Ritter says, offscreen: “Even longer if necessary.” Cut to Ritter, gesturing with a piece of sausage and saying, coaxingly, “Well?”

Slowly she goes to her knees again as the camera tracks in on her.

Back to Ritter: “That’s the girl.” Back to her, rising in pain to replace the back-rest.

The scene concludes with Ritter reminding Mrs. Dvorak that she’s in Gestapo headquarters. She acknowledges that she doesn’t expect to leave without giving information. He starts his questioning all over again as the scene fades out.

This quietly suspenseful scene establishes a bit of furniture as a key prop. Once the faulty back-rest is marked for our notice, we’re expected to remember that it’s a means of intimidation–something that Mrs. Dvorak, in her anxiety about refusing to aid the Nazis, twice forgets. Lang’s shots, simple and uncrowded, makes the chair, like the spattered mirror in The Enforcer, preserve the trace of human activity. Yet it’s more acutely integrated into the scene’s drama than the mirror, and remembering how it was used earlier makes us wait tensely to see how it will be used again.

Long-term density

Several scenes later, the Nazis threaten to kill four hundred Czech hostages if the assassin isn’t turned over to them. Mascha Novotny has set out for Gestapo headquarters to denounce the man she helped, but she changes her mind and decides not to betray her country. She will only plead for her father’s life. Once more we’re in Ritter’s office.

Centered in the frame, standing out as a pale oblong against the grayer background, the fateful chair is made salient during Mascha’s conversation with Gruber. I suspect there’s a sort of spatial suspense here–will she move to the chair and dislodge the precarious piece of wood?–but more important, I think, is the fact that the chair ineluctably reminds us of Mrs. Dvorak and her quiet resistance to pressure.

Ritter leaves to consult his superiors. When he comes back, a new composition keeps the chair prominent and lends a new centrality to the clock on Ritter’s desk, surmounted by a snarling cat or something like it. (It’s visible in shadow in the earlier scene with Mrs. Dvorak.) But now the camera arcs to minimize the Dvorak chair and show the beast and Ritter targeting Mascha.

Soon enough, as if to make sure we remember, Mrs. Dvorak is brought back in, having undergone serious torture. The camera positions reactivate our memories of the earlier scene.

As she continues to lie to protect Mascha, Mrs. Dvorak never touches the chair. Although she has been tortured, she seems wearily defiant, as if her refusal to aid the Nazis has given her some strength: no need to lean on the chair now. As a final cue to our memories, Lang has Ritter play once more with his riding crop, letting its shadow fall on her heart.

The threat is clear: For lying, the old woman will pay with her life.

The chair reappears in a later scene, but I’d argue that then it serves more as a pointer to another prop. The resistance movement fights back by framing Czaka, a beer baron sympathetic to the Nazis, as the assassin. Lang could have explicitly recalled the questioning of Mrs. Dvorak by having Czaka lean on the slat and knock it off. Instead, the composition makes Ritter’s clock more important than it was in earlier shots. As Czaka tries to defend himself, the framing blocks our view of the chair but emphasizes the snarling catlike creature on top of the clock. And the chair has shifted a little off and become a bit darker; it’s no longer as salient.

This cluster of scenes from Hangmen Also Die illustrates how scenic density can add layers to a film. One scene recalls another not only by similarity of situation and locale but by tangible marks left on it by earlier action. Having seen Mrs. Dvorak subjected to Ritter’s oily intimidation, we generally expect something like it to be applied to Anna. This conventional situation is given a rich, concrete presentation by the repeated camera positions and the simple chair that, unmoving, enters into the drama.

Of course as a Hollywood director, Lang was pressured to reuse sets and camera setups. That saved money and time. But he turned such repetitions to his advantage by letting certain objects come forward at crucial moments. They not only become part of the drama but prime us to remember them, and what they revealed, in ensuing scenes. And even though Lang never pursued the aggressive, packed deep-focus of other directors working in the 1940s, he shows how roomier, less pressurized compositions could still be charged with echoes of earlier bits of behavior.

Is this sort of visual-dramatic economy, calling on precise memories of concrete actions, lost in today’s American cinema? I suspect it is.

In studying Hangmen Also Die, I was curious about a perennial problem. Was the byplay with the chair a Lang invention on the set, or was it some version of the script, or in the original story by Lang and Bertolt Brecht?

The film didn’t have a secret script, as the poster says, but the sources do remain a bit obscure. A draft of the original story signed by Lang and Brecht, in that order, exists. It indicates only that the greengrocer, called Frau Blaschke, is subjected to eight hours of “the usual Gestapo brutality” and refuses to identify the girl. There were other drafts of the screenplay, but I don’t have access to them, if they exist, and standard sources on Brecht in Hollywood don’t mention this scene’s details.

Somewhere along the line, though, the chair-back business was concocted. I found the shooting script signed only by John Wexley (Brecht claimed that he was robbed of credit) and annotated in pencil, perhaps by Lang. That script indicates that Ritter’s room contains “a vacant chair with its seat close against desk.” and Mrs. Dvorak is standing beside it as the scene begins. Much of the dialogue is the same , with some slight changes notated in pencil, possibly by Lang. But the camera movements indicated are different from those in the final film, and more importantly so are the actions. After Mrs. Dvorak claims that she doesn’t know the woman who helped the assassin, we read the following. I indicate pencil notations with {}.

In her fatigue, she places hand on back-rest of chair. But its dowels are loose and back-rest clatters to the floor.

RITTER (saccharine): Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak.

CAMERA MOVES IN CLOSE as she obeys, stooping with painful fatigue–she has done this many times tonight.

RITTER: Now put it back in place, Mrs. Dvorak.

(She does so)

As Ritter questions her:

MED. SHOT – MRS. DVORAK. Without thinking, she is about to place hand again on loose back-rest–when she remembers and jerks back.

RITTER’S VOICE: Now don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak…I’m prepared to devote to you all of tonight–and even longer, if necessary.

Mrs. Dvorak, unconsciously reacting to this, once more rests hand on chair. {She jerks back but} The piece of wood clatters to the floor.

MED. SHOT – RITTER. Ritter waits patiently; when she doesn’t move, inquires:

RITTER: Well…?

CAMERA PULLS BACK to INCLUDE Mrs. Dvorak, who stoops to repeat painful routine. Ritter smiles approvingly.

RITTER: That’s the girl.

Nothing here is indicated about Ritter’s riding crop, nor does he initially knock the back-rest off the chair. Mrs. Dvorak does it herself, accidentally. And the scripted line is “Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak,” not, as in the finished film, “Pick it up again, Mrs. Dvorak.” The film version makes it clear that the byplay with the backrest is part of Ritter’s softening-up technique, something indicated in the script but not spelled out.

The later scenes in the film show other differences, mostly additions of things not mentioned in the shooting script. For instance, the script doesn’t mention the shadow of Ritter’s riding-crop. But the excerpt shows that the shooting script points toward some of the detailing we find in the finished film. It provides the sort of nudges that a director, especially one as oriented to gesture as Lang was, could elaborate on the set.

The Lang/ Brecht story has been published as “437!! Ein Seiselfilm,” in The Brecht Yearbook vol. 28: Friends, Colleagues, Collaborators, ed. Stephen Brockmann (2003), 9-30. The passage I mention, kindly translated for me by Ben Brewster, is on p. 16. Broader background on Brecht’s adventures in Hollywood can be found in James K. Lyon, Bertolt Brecht in America (Princeton University Press, 1980). Chapter 14 of Patrick McGilligan’s Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin’s, 1997) offers an account, mostly relying on Brecht’s viewpoint, of the making of Hangmen Also Die. The shooting script is in the John Wexley collection of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and the State Historical Society here in Madison. Thanks also to Marc Silberman, renowned Brecht expert, for advice.