Archive for the 'Film technique: Staging' Category

Sometimes a reframing…

Side Street (1949).

DB here:

…just knocks you out.

“It can only be fully recommended to those who have a deep and morbid interest in crime.” Snooty judgments like this made Bosley Crowther the critical joke of generations. Today film lovers wear their deep and morbid interest in crime as a badge of honor. Especially when the crime is covered by Anthony Mann.

In Side Street (1949), Joe Norson has lost his business and works part-time as a postman while he and his wife await their first child. Having come back from war and wanting to give Ellen a good life, Joe is tempted to steal money he’s seen lying around the office of a crooked attorney. He grabs a folder containing what he thinks is a couple of hundred dollars; instead, it holds $30,000 of blackmail money. The woman who chiseled the money out of a businessman turns up dead, and the police are investigating. When Joe naively loses the money and sets out to recover it, he’s drawn into the murder, tracked by the gang, and targeted as a prime suspect by the police.

Variety and Crowther chided the screenwriters for a sketchy plot, and the complaint is somewhat fair. Joe is an unusually weak protagonist. He botches both his theft and his cover-up, leaving a trail that’s easy for the killer and the cops to trace. Because Joe is fairly passive and on the run, and he has to follow his clues in a fairly linear manner, and his schemes to fight back come to almost nothing, the action is filled out by scenes of the gang and the police tracking him.

What partly compensates for the plot’s problems is the bold location shooting. As part of the semi-documentary trend of the period (the film opens and closes with worldly-wise voice-over narration from the Homicide Captain), Side Street presents itself as a story rooted in urban reality. And indeed it is a triumph of location shooting. The characters visit a bank, Greenwich Village, Bellevue Hospital, and many neighborhoods. The final chase, with Joe trapped in a taxi with the killer and pursued by three cop cars, is a tour de force of geometrical shot designs that make city canyons part of the drama.

Mann has long been praised for integrating the forces of nature into the action of his Westerns, but this film shows his flair for cityscapes too.

Given the constraints of location filming, the freedom of Mann’s camera is all the more arresting. This time he’s not working with John Alton, the cinematographer most in tune with his baroque sense of light and framing. But Mann still gets punchy results from ace DP Joseph Ruttenberg. There is nothing quite so staggering as Alton’s framing of Claire Trevor and the cabin clock in Raw Deal, let alone the Grand Guignol imagery of Reign of Terror, but Ruttenberg does give us plenty of nicely dense compositions, exploiting the verticals and apertures available on location. There’s also a neatly discreet shot of a revolver peeking out from behind a door in distant long-shot; the shadow supplies the telltale shape.

Mann is a post-Kane filmmaker. Like nearly every Forties director of dramas, he learned from Toland and Welles that it’s fun to shove the action into the viewer’s face. The high angles of the city are counterbalanced by steep, low setups both inside and outside. Mann never met a “Russian angle,” or a ceiling, he didn’t like.

When the lens is more or less straight on, the frame can be tight and actors’ heads are packed into the frame like cantaloupes in a supermarket display.

In motion, the camera isn’t safe. Actors rush past the lens or thrust themselves straight at it.

When Joe flings himself out of a car, prepare to find yourself in the middle of traffic, with a truck rushing at you (a stunt done in real space, not against a back-projection).

Yet even studio-shot back-projections retain vigorous, immersive depth.

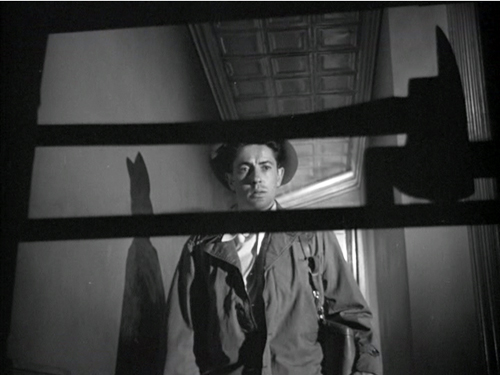

Mann’s visual dynamism, complete with aggressive foreground and distant depth, hits a high point in the dialogue-free scene that’s the topic of today’s sermonette. Joe hasn’t planned to steal the money, but circumstances lure him on. The lawyer’s out of his office, and the door has been left ajar. Joe earlier saw the money put into a file drawer, and as Joe prepares to slide the mail under the door, the cabinet stands temptingly in the foreground.

He impulsively heads for the cabinet, pauses before it, and then—thanks to an abrasive cut—grabs the handle violently. The drawer is locked. He recovers himself, almost grateful that he’s blocked, and he lurches out the door. No theft today, apparently.

Outside, Joe seems to be going on his way, but the long shot shows a barrier, like a railing in the foreground. It seems about as innocuous as the car hood we saw when Joe went in the building.

As Joe approaches, the camera tilts up to follow him and he stops, staring. He’s framed before what’s now revealed as a fire axe.

Another director—Hitchcock, perhaps—would have handled this with a medium-shot of Joe leaving and looking off, followed by an optical POV shot of the axe. Or you could show him leaving in the foreground, with the axe mounted in the distance; he glances back, sees it, and decides to go fetch it.

By contrast, Mann’s approach yields a sharp one-two snap: Joe approaches/ he stops. We see the axe, but almost by accident; the reframing is just following Joe’s movement. And we don’t need to see any more of the thing but its distinctive shape—its pure axe-ness given in silhouette. Rudolf Arnheim, who always advocated pictorial simplicity, would be pleased.

After a beat, in an abrupt cut, Joe grabs the thing.

He lunges down the corridor back to the office and starts to break into the cabinet. Now his violent adventure begins.

Crime I’m not so sure of, but with bodacious filmmaking like this, who wouldn’t acquire a deep and morbid interest in cinema?

It’s been too long since our last “Sometimes…” entry. For the others see: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…”

Bosley Crowther’s review of Side Street is “The Screen: New Crime Story,” New York Times (24 March 1950), p. 29.The Variety reviews, more or less identical, are in Daily Variety (22 December 1949), p. 3, and Variety (28 December 1949), p. 6. The Times covers the shooting of the climactic chase in “Taxi Acrobatics in Wall Street” (8 May 1949), X5.

For more on the postwar cinema’s love affair with vigorous depth staging and depth of field, see this entry on Bergman and Antonioni, this entry on Toland and depth of field, this entry on Manny Farber’s objections to Huston, this entry on dense staging, and this entry on Wyler’s staging in The Little Foxes. For much more see Parts Three and Four of our Film History: An Introduction, Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Side Street.

Watch those hands; or, Burt, Jean-Luc, and Bill come to Cinephile Summer Camp

Nouvelle Vague (1990).

DB here:

At this year’s Summer Film College in Antwerp, Peter Bosma pointed out that the event seems to be a unique mixture.

Films are screened from morn to midnight: this time, 38 films across 6 days and two half-days. But it’s not exactly a film festival, as there are no new releases.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

Moreover, the films cluster around two or three major themes. This year we had Late Godard (fourteen titles, counting episodes of Histoire(s) du cinema) and the career of Burt Lancaster (eleven). In addition, there were nightly showcases called “Masterworks in Context,” which included one surprise film, title undisclosed. But unike most movie marathons, the Summer Film College introduces screenings with lectures and discussions. This year there were fourteen sessions, each running about ninety minutes. These are serious, intensely informative talks—very far from the usual brief introductions one gets at festivals or in art house warm-ups.

So is it an educational enterprise? Definitely, but without assignments, tests, or grades. It’s designed to serve Flemish-speaking professors and students, but also civilians who are just interested in a weeklong package of film and film talk. The event helps forge a community of film appreciation.

Finally, there’s often a guest filmmaker on hand, usually related to the main threads. This time it was Bill Forsyth, who directed Burt in Local Hero. That film was screened, along with Bill’s wonderful Housekeeping.

So what would you call the College? I once called it Cinephile Summer Camp, and that still seems accurate in evoking the sense of fun and camaraderie that pervade the place. We don’t all get mosquito bites, but after a week you come to enjoy seeing familiar faces and talking with them about what they’re seeing. Just as when you go to summer camp, you get to stay up late. But at no summer camp I ever attended did we drink so much beer.

JLG/SJ/DB

The principal speakers were Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers, who covered Burt, and Steven Jacobs on Late Godard. The Masterworks in Context shows were introduced by several guest speakers, including Lisa Colpaert (excellent on I Walked with a Zombie) and Vito Adriaensens (covering both Murder! and Vampyr). For Pollyanna, Bruno Mestdagh of the Cinematek staff explained the process of restoration. I played utility infielder, offering one talk on Burt and three on JLG.

How often do you get to see 35mm prints of Une femme mariée, Passion, Je vous salue Marie, Détective, JLG/JLG, Eloge de l’amour, and Nouvelle Vague? The Godard series, which ended with a 3D show of Adieu au langage, was a high point of my summer viewing. Back home I had prepared by rewatching all Godard’s features from Sauve qui peut (la vie) onward, but my video homework didn’t prepare me for the way the big screen amps up their prickly, seductive power.

I don’t speak or read Dutch, so I missed many subtleties in Steven Jacobs’ talks, but thanks to Power Point I could figure out the main points. Few lecturers can pack so much information and ideas into ninety minutes.

We had no way of knowing how familiar the audience was with Godard, early or middle or late, so Steven started with an orienting talk on JLG’s pre-1980 work (above). He swiftly reviewed key aspects of Godard’s New Wave period, traced his shift toward “a critical cinema” between 1967-1969, and explored the move into his Marxist phase. Along the way, he stressed the way cultural developments like auteur theory, Pop Art, Maoism, Brechtian theatre, and semiotics shaped Godard’s films. Particularly acute was his discussion of the “one image after another” sequence in Ici et ailleurs (1975). In all, the talk was an ideal prelude to Une femme mariée, which pointed up so many motifs of the later work: the focus on the couple, the emphasis on media-based images, and the persisting shadow of the Holocaust.

Steven is an art historian at University of Ghent; he earlier appeared on this blog as co-author of the imaginative book The Dark Galleries. After tracing Godard’s return to mainstream cinema and his move to Rolle, Switzerland, Steven focused on that splendid example of JLG the painter, Passion. Steven has written eloquently on the film in his Framing Pictures, and here he widened his focus to discuss its relation to other films centered on the tableau vivant, like Pasolini’s La Ricotta and Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting.

You’d expect that Steven would have a field day with Histoire(s) du cinema, and he did. Unlike most Godardophiles, I’m not wild about this series of video essays. I can’t take them as serious studies in film history, and too often I sense he’s just playing around. (Enough with the stroboscopic flashes, okay?) But Steven obliged me to rethink them by showing how they fit into the Postmodern art scene, especially the video art movement after the 1970s. He pointed out the central importance of the Hitchcock episode and the series’ constant concern with the Holocaust, often in dialogue with Shoah. Citing Godard’s claim that video taught him to see cinema in a new way, Steven suggests that the format also created a tenor of paradoxical melancholy. It’s as if JLG’s experiments with this new technology drove him to celebrate the death of the cinema he knew.

My three talks on Late Godard tried to ask something that I didn’t find many traces of in the literature. What are these films doing with (or against) narrative? I think that the focus on JLG as “film essayist” has sometimes obscured the fact that he has long insisted that he needs stories. Yet he seems to have no interest in the craft of storytelling as we understand it. He avoids dense exposition, careful foreshadowing, well-timed revelations, and cumulative climaxes. He tends to spoil the narrative expectations he sets up.

As a result, his plots—for his films have them—are distressingly opaque. Exactly what happens in a Late JLG film is often difficult to determine. I’m always surprised when discussions of these late films provide capsule plot summaries, for the very difficulty of arriving at these should claim our attention. As just one instance, many critics seeing Adieu au langage for the first time thought the film centered on one couple. It centers on two. But the fact of that mistake ought to interest us enormously: What in the film’s presentation made it difficult to follow the basic situation? Are there strategies Godard follows in creating his apparently willful obscurity?

Godard’s unique strategies of storytelling are carried down into felicities of visual and verbal style. Again, I think that critics haven’t sufficiently acknowledged just how strange and opaque the surfaces of these movies are. For one thing, characters are unidentifiable from scene to scene, thanks to camera setups that cut off their faces, wrap them in shadow, or leave them offscreen altogether.

I’ve touched on these matters earlier (here and here), but just as a quick example, consider this shot from the opening of Nouvelle Vague. It has to be one of the most oblique introductions to a protagonist we can find in cinema.

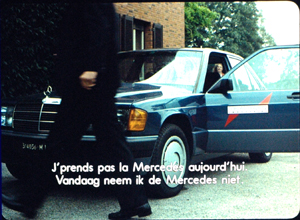

Corporate owner Elena Torlato Favrini strides out of her mansion past her chauffeur while taking a transatlantic call. Any other director would favor us with a close view of her, perhaps tracking as she cuts a swath through her entourage. Instead we get a shot framing her chauffeur climbing out of their Mercedes.

As he crosses in front of the car, we hear her on her cellphone. She can be glimpsed fleetingly in the background, through the car window.

She approaches us, becoming briefly visible as she passes the car, but when she stops, she’s decapitated. We don’t get anything like a good look at her, and the locked-down camera refuses to reframe her. Instead, the framing emphasizes her slipping on her gloves.

The gesture ties into other imagery in the film. A little before this shot, there’s an isolated shot that establishes hands as a major motif in the film. But we should also notice that this fairly abstract shot also presents the gesture of Elena slipping on a glove. Or rather, it almost presents it, as the shot is abruptly chopped off just as the gesture begins.

So slipping on the glove, started in an earlier shot, is finished at the Mercedes. But just as important, the visual idea of a hand gesture broken by a cut resurfaces at the climax. When Richard Lennox helps Elena out of the water, the action is also incomplete. Only five frames show him grabbing her arm before a cut interrupts the action.

Another filmmaker would have held the image on that triumphant grip, but Godard denies us this little burst of satisfaction. Of the five frames in this bit of the shot, there is just one frame showing Richard’s hand seizing her. Godard again spoils a solid narrative effect. But he does narrative in his own way, with the broken-off gestures counterpointed by the hands that do meet at other points in the film.

Every scene in Nouvelle Vague, and most scenes in Late JLG, seem to me to be built on one or more fine-grained pictorial and auditory ideas like these. Those ideas can seem perverse, as in the chauffeur scene: why let us see his face but play down Elena’s? He’s not a major character; we don’t even learn his name until the film’s final moments. Unhappily, this peculiar instant of comparison is lessened in the 1.66 version of the film available on DVD. That image suppresses the driver’s face no less than Elena’s, losing Godard’s peculiar version of “gradation of emphasis.”

All the more reason to try to see these films in their full-frame glory, as I’ve argued before.

BL (Beautiful Loser)/AB/TP

Criss Cross (1949).

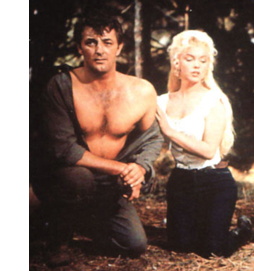

With big tousled hair, unadulterated sinew, and teeth gleaming like a Pontiac grille, Burt Lancaster came to fame in the late 1940s. He belonged to a new cohort of actors quite different from the 1930s Debonairs (William Powell, Melvyn Douglas, Cary Grant) and the Bashful Boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart). Yet the new lads were also at variance with the rugged Ordinary Joes (Cagney, Bogart, Tracy, Gable).

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

Of the group, Burt had probably the strongest A-list career overall. He fostered a great variety of projects. Who else of his generation appeared in films by Visconti and Malle? What other unflinching liberal was prepared to play a US general bent on a coup (Seven Days in May) or a conspirator behind the Kennedy assassination (Executive Action) or an obstinate officer fighting in Vietnam (Go Tell the Spartans)? He portrayed a renegade officer demanding the revelation of the brutal policy behind the Vietnam War (Twilight’s Last Gleaming). His closest rival and frequent costar Kirk Douglas didn’t enjoy such a vigorous and prestigious twilight. Only Brando kept beating him to the prize: Burt wanted to play the lead in Streetcar Named Desire and The Godfather. Unpredictably, he wanted as well to play the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman.

I had had only slight interest in Burt as a star before this edition of the Summer School. But listening to the talks, seeing the films, and preparing my contribution made me realize how extraordinary an actor he was, and how important in Hollywood postwar history. Burt was well-served by the fine lectures offered by Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers.

Anke provided an in-depth survey of how Burt and the Brawny Gang brought to a new level the culture of male athleticism—on display in Fairbanks and Valentino, developed further in the body-building craze of the 1930s, and culminating in what one 1954 magazine article called Hollywood’s “Age of the Chest.” She brought in forgotten pin-up boys like Guy Madison and pointed out how Burt and his peers paved the way for Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis. Anke went on to specify Burt’s beefcake persona, established in The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and locked into place in The Crimson Pirate (1952), which we saw. In her followup talk next day, she surveyed Burt’s place in the industry. He was one of the few stars to supervise a successful independent production company, Hecht Hill Lancaster (earlier, Norma Productions and Hecht Lancaster).

Tom moved on to consider Burt’s star charisma. He traced how Burt adjusted his authoritative image to different roles—the con man, the confident leader, the embittered idealist. Tom was especially good at analyzing Burt’s acting technique, tying it to particular trends in theatre and film of the time and pointing up the physicality of his performance of specific, precise tasks. Given the standard situation of rigging a bomb, he contrasted Burt’s meticulous finger work in The Train (1964) with that of Kirk going through the motions in The Heroes of Telemark. Tom even spared some time for Burt’s diction—a quality that really popped out when we watched Elmer Gantry (1960).

In a later lecture, Tom surveyed “Late Burt,” and his relation to political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He followed that with a revealing account of Burt’s relation to the trend of “Mexican Westerns” launched in the 1950s. Another arc in Burt’s career: from Vera Cruz (1954) to Ulzana’s Raid (1972), with The Professionals (1966) in between. That we saw in another gorgeous print.

I could go on a lot more about Tom and Anke’s lectures, but I don’t want to give away too much. The talks contained so much original research and discerning analysis of both the films and trends within film history that I’m hoping Tom and Anke will lay these ideas out at book length. Part “star study,” part film criticism, part industry history, their lectures were exhilarating.

My own contribution was minimal, a talk on First-Phase Burt. The Brawny guys were well-suited to the trend toward hard-boiled movies, those crime pictures we later decided to call “noirs.” Those weren’t usually suitable for older players (though there were some makeovers, such as Dick Powell and Fred MacMurray). To fill these roles came Alan Ladd, Glenn Ford, Dana Andrews, and Richard Widmark, along with the beefcakes. At the same time, “independent” producers within the studios began contracting their own new talent and loaning it out. Burt was signed by Hal Wallis at Paramount, who also had Kirk Douglas, Wendell Corey, and Lizabeth Scott in his stable. Films like Desert Fury (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) were Wallis package projects.

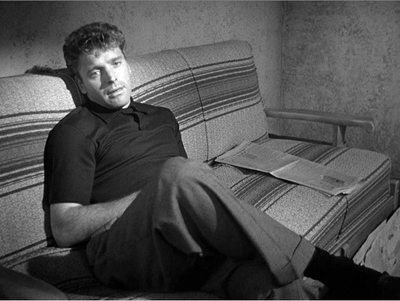

Hired straight from the stage with no film experience, Burt debuted as the Swede in The Killers (1946), on loanout to Mark Hellinger at Universal International. Burt benefited from a galvanizing entrance. Lying on a bed in the dark, refusing to flee the hitmen on his trail, Burt is a shadowed, curiously languid torso in a tight undershirt.

Only after a beat do we see something else: massive hands rubbing a weary head. Soon that head is revealed.

As the killers burst in, the whole image comes together.

Has a Hollywood beginner ever been given such a gift as this opening?

With this onscreen wattage, it’s all the more striking that this young discovery is curiously absent from his early films. He’s onscreen for only a third of The Killers’ running time, and not even half of Brute Force (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number. The film Wallis wanted to be his debut, Desert Fury (1947), gives him only twenty-three minutes out of ninety, and in the second male lead at that. All My Sons (1948) puts him in an ensemble drama. I Walk Alone (1948), the Norma production Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), and another Universal project, Criss Cross (1949) start to make him a proper, central protagonist. By then, he is ready to become the star attraction of the swashbuckling films.

Moreover, in his early phase, he mostly plays losers. Not the brightest guy in the room, he’s easily suckered by a femme fatale in The Killers and Criss Cross. He makes amateurish mistakes at crime (Sorry, Wrong Number) and, coming out of prison, he is the last to realize the rackets have gone corporate (I Walk Alone). At the start of Kiss the Blood he punches a man too hard and kills him. He’s caught and whipped and imprisoned, and when he comes out he stumbles back into crime again. He’s shrewd enough to set up a prison break in Brute Force, but so doggedly determined is he to reunite with his girl on the outside that he launches a suicidal bloodbath.

When he finally catches on to his fate, we get expressions ranging from stupefaction to anguish (The Killers, Criss Cross).

He even cries (All My Sons, Kiss the Blood).

Loser or winner, when he is onscreen, he has the outlandish physical presence of the born star. Most obvious is a physique (Kiss the Blood, Brute Force).

Even his back, featured with a prominence we get with few other actors, is straining against a drenched prison uniform (Brute Force) or a tailored suit (Criss Cross).

The face was a cameraman’s dream; it could be craggy or somber, thoughtful or tormented (The Killers, Brute Force x2, Criss Cross).

He can be stiff-armed and zombielike coming out of prison in Kiss the Blood, but he can also gamely cock his elbows, ready to spring, like Cagney and Cary Grant (I Walk Alone).

The enormous hands, which look likely to crush a skull (Criss Cross) or rip apart a phone cord (Sorry, Wrong Number), could be surprisingly delicate, tentatively touching his girlfriend’s wheelchair or laying down plans like playing cards (Brute Force).

In The Killers he makes skillful use of those hands, pocketing his busted one or spreading out the scarf given him by the treacherous Kitty.

Easily taken in by Kitty’s plan, he seems to have a qualm when his gripping embrace relaxes and the fingers splay in hesitation.

This sort of handwork would become crucial, as Tom pointed out, to Burt’s performance style, particularly in The Birdman of Alcatraz.

“I’d never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s,” Norman Mailer once said. You can see what he meant.

Again, though, the actor is in control. Some years back I wrote that eyes by themselves aren’t very expressive: the eyelids, eyebrows, and mouth tell us more. I still think that’s right, but Burt manages to convey the sense of the beast at bay with remarkable control of just the eyeballs. He seems to be looking for an escape hatch without moving his head an inch.

While Burt was playing losers, his counterpart Kirk Douglas was often playing heels—cynical manipulators who stomp on everybody else, as in I Walk Alone. Sometimes Kirk learns his errors (Young Man with a Horn, 1950) but several roles of the period, in Out of the Past, Champion, and Ace in the Hole, make him a glib villain or tawdry antihero. Somewhat later Burt explored this characterization too, notably in Vera Cruz, Elmer Gantry, and The Rainmaker (1956). How did he shift from the beautiful loser to the fast-talking con artist?

I think there are hints from the start. In The Killers, after he’s washed up as a fighter, the Swede goes in for street crime. When he confronts his old friend the cop, Lancaster brings those arms and hands into play. In his enormous unstructured topcoat, he lifts his fists up to his waist. It’s both the businessman’s getting-down-to-brass-tacks sweep, but also a kind of puffing up, exposing that massive frontal expanse. Little Sam Levene can grasp his lapels, but he doesn’t stand a chance against this.

Burt uses the same imperious gesture when, in Sorry, Wrong Number, he’s trying to bully a company employee into joining a crooked deal.

In these noir movies, his intimidation of others won’t put him ahead of the game. But perhaps these arm movements begin to sketch a more flamboyant loser like Gantry. By striking what actors used to call an “attitude,” Burt could start to build an entire character: a hell-for-leather charlatan.

Seeing the films, listening to Tom and Anke, and studying Lancaster’s work on my own brought home to me again the importance of the details of performance and the presence of a star. These movies would be utterly different if Mitchum or William Holden played the Burt parts. Our actors don’t wear masks or Hazmat suits. We’re powerfully affected by what they bring to the character in voice, body, face, and gesture—the expressive dimensions of cinematic presence.

BL/JLG/BF

College coordinators Lisa Colpaert and Bart Versteirt, flanking Bill Forsyth.

What do Burt and JLG have in common? For one thing, some images from Criss Cross in Histoire(s) du cinema 1a (see above). For another, Bill Forsyth.

With the success of Gregory’s Girl (1981), Bill was invited by David Puttnam, then at Columbia, to make a Scottish movie with a couple of American actors. The result, Bill says, now looks to be a “soft-core environmental movie.” Local Hero (1983) remains much loved, and for good reason. It makes nearly all of today’s multiplex raunch look adolescent. It has a tone of civility, an embrace of eccentricity, and a genuine interest in people reminiscent of Ealing comedies. For me it’s a masterpiece of sweet, light-hearted art.

Local Hero feels loose and leisurely, but it’s actually a very economical movie. The first few minutes should be studied by screenwriters interested in tight exposition and fast attachment to a protagonist. It’s peppered with sidelights on its central drama, such as the Russian’s song about how “even the Lone Star State gets lonesome.” That neatly sums up the situation of the yuppie sad sack MacIntyre (“I’m more of a Telex man”) learning about village life. As usual, I was moved by Mark Knopfler’s plangent score, the electronic overtones meshing with the pulsations of the Northern Lights.

Burt’s role is that of CEO deus ex machina. Having assigned Mac to buy a Scottish seacoast town for an oil refinery, Mr. Happer eventually descends in his chopper and decides to establish a laboratory there instead. Burt’s crisp delivery and tight fingerwork are still on display at age seventy. The other actors don’t use their hands as much as he does–partly so they’re not distracting us from him, I suspect, but also because newer-style Hollywood acting doesn’t encourage it. In any case, as usual Burt uses his acrobat’s sense of physicality to intensify his performance. Even clasping his hands behind his back tells about the character’s authoritative dignity.

Bill learned that Burt regretted not doing more comedy, so he wrote the mogul’s part with him in mind. Burt signed on eagerly. He showed up on the set with a full beard, hoping Bill would let him keep it; they compromised on a mustache.

Bill had worked mainly with teenage actors on That Sinking Feeling (1979) and Gregory’s Girl, so Burt was really the first adult performer he ever directed. Across their three weeks together, Burt demanded nothing, except that he wanted to loop his dialogue. Bill preferred not to loop, and as it turned out only one scene needed to be rerecorded.

Burt and Bill skipped lunch in order to prepare the next scene, becoming “lunch bums.” Bill remembers Burt hanging out with the other actors and chatting with extras. He freely made fun of Bill’s accent: “”He speaks no known language.” He told Bill: “I don’t know what you’re saying, but I know what you mean.”

Bill talked as well about his own career. Starting out in the days before home video, he learned dialogue and pacing by audio taping classic films. (Sounds like a good idea to me.) He became a performer’s director. “The only thing I’ve ever said to a cameraman is: ‘Accommodate the actors.” He quoted Burt approvingly: “The space in front of the camera is the actor’s space.”

What’s the connection to JLG? It turns out that Godard was the director Bill most admired in his salad days. During the 60s he sated himself on art cinema, especially New Wave imports. When he saw Pierrot le fou, he left the theatre stunned. Godard became “the master. He still is, for me.”

Accordingly, Bill’s earliest cinema efforts were in an avant-garde vein. One piece, puckishly called Film Language, started with ten minutes of black leader while a text by Beckett was read out. Another, Waterloo, included a vast ten-minute shot in which the camera left one household, climbed into a car, rode a great distance, and ended up in another home. The film played at the Edinburgh film festival to an audience of 200. By the end three viewers were left. “I’d moved my first audience.”

Bill remarked that he sometimes regrets not sticking with experimental media. Today, he says, he might be a video-installation artist. A teasing idea. But we should be grateful that we got his features. I don’t know if Jean-Luc would agree, but I bet Burt would.

Thanks to Bart Versteirt, Lisa Colpaert, and their colleagues for a great week. Thanks as well to the participants, whose willingness to take on anything we threw at them was very encouraging. And a farewell to two friends who have projected films at every Summer Film College I’ve attended over the last sixteen years: Esther Dijkstra and Joost De Keijser. They have helped make the event the splendid enterprise it is.

Peter Bosma’s informative book Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives is available here.

A detailed “index of references” for Histoire(s) du cinema is provided by Céline Scemama.

Our first encounter with Bill Forsyth was at Ebertfest. For more on actors’ handiwork, try this entry.

An eager crowd of campers awaits Adieu au langage.

Hou Hsiao-hsien: A new video lecture!

The Puppetmaster (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1993).

DB here:

The Hou Hsiao-hsien seminar held in Antwerp at the end of May was an event I was sorry to miss. The title announced a focus on Hou’s style of “just-noticeable differences,” a phrase I used to describe his rich and nuanced staging. Coordinator Tom Paulus assembled a stellar lineup of scholars:

Cristina Álvarez López, critic and researcher, co-founder and co-editor of Transit and frequent contributor to mubi.

Adrian Martin, wide-ranging critic and scholar, whose recent book, Mise en scène and Film Style, made him a natural choice for this gathering.

Bérénice Reynaud, expert on Chinese cinema and author of the first book on Hou in English, a fine monograph on City of Sadness.

Richard Suchenski, coordinator of the major Hou retrospective now touring the world and editor of a vast anthology (discussed in an earlier post).

James Udden, author of the first career monograph on Hou in English (discussed hereabouts) and reporter for us on The Assassin (here and here).

A bout of bronchitis kept me home. Chris Fujiwara, author of books on Preminger, Jerry Lewis, and Jacques Tourneur, kindly filled in for me.

But I had prepared a talk, dammit, and I chafed at the prospect of junking it.

The talk was called “The Drawer, Two Women, and the Little Toy Fan.” It centered on aspects of Hou’s 1980s and 1990s work that seemed to me to have influenced works by other filmmakers in the region. The talk ended with some speculations on developments in Hou’s own films over the last fifteen years.

Remembering that all redemption comes from the Web, I decided to put the thing up on our Vimeo channel. While fiddling with it, I realized that it was pretty narrowly addressed to Hou specialists. So I expanded it by offering more context and background, and gave it the unsexy title of “Hou Hsiao-hsien: Constraints, traditions, and trends.”

The lecture is available here on my Vimeo channel.

It can serve as an introduction to some ideas about Hou I floated in Figures Traced in Light. I’ve added comments on Hou films after Flowers of Shanghai, and I consider other filmmakers (Kore-eda, Tsai Ming-liang, Edward Yang) as well. It has pretty pictures, many drawn from 35mm prints.

I regret to report, though, that my voice-over narration, the first I recorded at home rather in a studio, is a bit ragged. And, sorry to say, the talk runs nearly seventy minutes. I take consolation in Adorno’s reply to someone who complained that The Authoritarian Personality was too long: “We didn’t have time to make it short.”

Thanks to Tom Paulus of the University of Antwerp and the Photogénie blog for sponsoring the seminar. Thanks as well to Bart Versteirt and Lisa Colpaert of the Vlaamse Dienst voor Filmcultuur vzw and to Nicola Mazzanti of the Cinematek. And of course I owe big thanks to Erik Gunneson of our department of Communication Arts who, as ever, helped me record and post the video lecture.

See our previous entry for more information about events related to Hou’s visit to Belgium. Our site has other material on Hou here and especially here and here.

Here’s a good place to acknowledge what Abé Markus Nornes and Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh have done in making available their pioneering work on City of Sadness. Long ago they put up a fascinating website on the film, which they have now updated on several platforms. Staging Memories, the free interactive iBook for Mac and iPad, can be downloaded from the Apple Bookstore. You can buy a paperback edition from Michigan Publishing here, and the PDF version of that can be viewed for free here.

In the talk I mention how Hou’s work has affinities for the “tableau” style developed in the 1910s. This isn’t a question of direct influence, but an instance of convergence: Similar early choices in a process (long take, long shot, fixed camera) led to similar options and opportunities further down the line. (A case of path dependence in film style?) You can find more on the tableau style in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and some entries on this site, particularly this one and these. The tableau style is also discussed in another video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Olivier Assayas and Hou Hsiao-hsien at the Master Class held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. Photo courtesy Nick Nguyen.

Problems, problems: Wyler’s workaround

The Little Foxes (1941).

DB here:

For me, shooting is a struggle where you only get to be happy for five minutes before you start thinking about the next problem to solve.

Ruben Ostlund, on Force Majeure

One of the most famous shots in American cinema occurs at a climactic moment in The Little Foxes (1941). Regina Giddens has just learned that her sickly husband Horace has let her brothers get away with a business deal that double-crosses her. They will reap all the rewards of bringing a factory to town, while she, who engineered the deal and expected Horace to fall in line, will get nothing. Horace is already not far from death, and their quarrel in the parlor precipitates a heart attack. He spills his bottle of medicine and needs some from his upstairs supply.

Regina refuses to go fetch it, and instead Horace must stagger up and out. While she sits, fiercely waiting, on the sofa, he tries to pull himself upstairs, but he collapses on the steps. Once he has fallen, and perhaps died, she stirs to action and rouses the household.

Lillian Hellman’s original play had been a Broadway success, and this was one of the most notable scenes. How did Wyler stage it? Very oddly, as the frame up top suggests. We can’t really see Horace’s struggle on the stair. Not only does the camera put Regina in the foreground, but Horace is out of focus in the rear, at least until she rises whirling and runs to the background, the damage done.

Why did Wyler stage it this way? It depends, as Bill Clinton might say, on what your definition of why is.

Deeper, closer

1941 was the breakout year of deep-focus filmmaking in Hollywood. Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, Kings Row, Ball of Fire, I Wake Up Screaming, How Green Was My Valley, and several other films set the pace for a new stylistic option. In this style, the action is staged in depth rather than perpendicular to the camera, as most scenes in Hollywood cinema were. And the camera lens creates depth of field, in which even fairly close foreground planes are just as sharp as the action in the rear. Such images weren’t unknown before; we can find them in silent cinema. But from 1941 on, depth staging accompanied by depth of focus would be increasingly common in Hollywood dramas, from thrillers and melodramas to film-noir exercises. Not all shots would be designed for maximal depth; continuity editing and closer views would still be used. But we do find such imagery becoming more common, particularly at moments of tension.

Cinematographer Gregg Toland is usually cited as a main source of this trend, and his work on Kane and Ball of Fire, as well as Ford’s Grapes of Wrath (1940) and The Long Voyage Home (1940), became models of the new look. Toland also worked with Wyler on several films, including The Little Foxes. But even without Toland, Wyler had in some films cultivated a deep-focus look (as had Ford). Coming when it did, The Little Foxes proved a powerful demonstration of the deep-focus style.

Three aspects stand out. First, there’s a certain economy of presentation. As Wyler and others pointed out, depth imagery permits directors to minimize editing. Instead of cutting from action to reaction, we see both at the same time.

Wyler suggested in publicity of the period that this gave the viewer more freedom of where to look, and André Bazin seized upon this rationale as part of his aesthetic of realism. Just as in the real world, in some films we must choose what to pay attention to.

But The Little Foxes went beyond the moderate deep focus of Stagecoach and other films to create very aggressive images. This is the film’s second novelty. Several shots place the foreground very close to the camera. As a result, we get looming faces or objects in the front plane, and we still see well-focused dramatic elements behind.

A third source of power is less noted. In The Little Foxes, Wyler found ways to make deep shots comment upon the plot. For instance, the action offers Regina’s daughter Alexandra, usually called Zan, a choice of being more like her mother (tough and vicious) or her father (tolerant and gentle). At other points Zan is paralleled to her ineffectual, alcoholic aunt Birdie. At one point, Birdie has predicted that Zan may wind up like her.

In a theatre production, there would be many staging strategies that would create these parallels, but Wyler uses a particularly striking one. One evening, while Regina and her brothers plot their scheme, Birdie has been relegated to a chair far from the discussion.

The composition diagrams Birdie’s situation in the scene and her place in the family. Then Wyler cuts in to her.

This might be seen as a bit of heavy-handed emphasis, but actually he’s doing two things. He’s making manifest her reaction, a numb resignation to being excluded. He’s also setting up, thanks to another depth composition, the chair in the hallway by the staircase. At the climax, it’s Zan, as beaten down as Birdie, who slumps in that chair.

Thanks to depth staging and deep-focus cinematography, the second image emphasizes Birdie’s solitude and prophesies Zan’s.

Which only makes my first question more pressing. Some shots of the quarrel leading up to Horace’s collapse on the stair exhibit flagrant deep focus.

We know from other shots in the film, like the Birdie/Zan comparison, that Wyler could have simply shown us Regina on the sofa in the foreground, in long shot or medium shot, while keeping Horace in focus in the background. In fact, Wyler tells us that Toland said, “I can have him sharp, or both of them sharp.” Why opt for shallow focus that makes Horace’s staircase seizure blurry and hard to see?

Fun with functions

Asking why? about something in an artwork actually veils two different questions.

The first is: How did it get there? The answer is a causal story about how the element came to be included.

The second sense of why is: What’s it doing there? That’s not a question of causes but of functions. How does the element contribute to the other parts and the artwork as a whole?

Take the second question first. You can imagine many functional reasons for Wyler’s choice. Exactly because the rest of the film keeps image planes sharp, this moment gains a unique emphasis. Horace’s collapse is marked as a major turning point in the plot. In an ordinary film, we wouldn’t notice an out-of-focus background. Here, by reverting to the more traditional choice, Wyler makes shallow focus stylistically prominent. For once in a film, a dramatic high point isn’t given to us with maximum visibility.

Another function is character revelation. In the film as a whole, we haven’t been consistently restricted to any one character. Here, Wyler could have concentrated on either Horace or Regina, or he could have given them equal treatment. An obvious choice would have been intercutting shots of Horace crawling up the steps with shots of Regina, impassively turned from him. Probably most directors would have done it that way.

Alternatively, we might have been attached to Horace, letting us see Regina in the distance. That would have diminished her reaction and played up Horace’s suffering.

Wyler’s choice puts the emphasis not on the action—thanks to the distant framing, Horace’s collapse can almost be taken for granted—but Regina’s reactions, or rather non-reactions, moment by moment. We’re made to see her turning slightly to listen to his struggles, while her staring eyes suggest that she’s visualizing the action with a horrified fascination. It’s as if her denying him the medicine was an experiment in seeing how far she could go. Now she knows. Her straining face is virtually willing her husband to die.

Keeping both this monstrous woman and her victim in focus would have divided our attention, then, and Wyler wants it squarely on Regina. He seems to have said as much in interviews.

We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.

I wanted audiences to feel they were seeing something they were not supposed to see. Seeing the husband in the background made you squint, but what you were seeing was her face.

The second remark suggests another functional result of Wyler’s choice. By making the collapse almost indiscernible, we become very aware of what we can’t see. Thanks to selective focus, Bazin remarked, “The viewer feels an extra anxiety and almost wants to push the immobile Bette Davis aside to get a better look.” The dramatic tension of the scene finds its counterpart in our frustration to see what any other film would show us.

Finally, we should note that the staircase is an essential element in the film’s drama. Horace’s collapse is only one major incident taking place around and on it. Significantly, when Zan finally breaks free of Regina and the rest of the family, the matriarch learns of it standing on the stairs. Having all but murdered her husband there, now she sees her daughter abandon her.

Shoot my good side

The Bishop’s Wife (1948).

There are other functions we, as good critics, might seek out. For all of them, there is probably a loose causal story we’re relying on: Wyler and his colleagues made some choices that bore fruit. Some of those choices may have aimed at fulfilling the functions we notice. Other functions we notice may come along as bonuses—unintended but still benefiting the scene. Unintended consequences, good or bad, come up in art as elsewhere.

There remains the other implication of why-did-they-do-it questions: the one that seeks out quite specific causes that govern the scene. How do we tackle that?

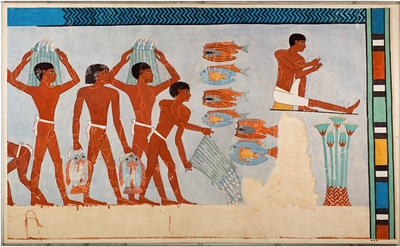

In my book On the History of Film Style, from which some of these Little Foxes observations are drawn, I argued that we can make stretches of stylistic history intelligible by thinking in terms of problems and solutions. Art historians have done this for a long while. Assuming that you want to suggest that something in the picture is farther away than something else, how do you do it? One way is through overlap, as in Egyptian art. Here the fishermen overlap the background, their legs overlap each other’s, and the strings of fish that one is carrying overlap some legs.

Later image-makers suggest variable distances through size variations, placement in the format (a little bit of that here, with the river above/behind the men), tonal contrast, atmospheric perspective, linear perspective, and other techniques. These can be considered solutions, available to artists of different times and places, to the problem of suggesting three dimensions on a flat surface.

A problem/solution way of thinking can clarify some developments in the history of filmmaking too. If you have to represent two actions taking place simultaneously, how can you do it? Crosscutting, as Griffith and others showed in the 1910s, solves that problem. It offers spillover benefits too, such as controlling pace. Similarly, there’s the problem of representing spoken dialogue. Silent films solved this in various ways—through a commenter in the theatre (the benshi in Japan), through actors voicing the roles behind the screen, and most commonly through intertitles. Later, synchronized sound solved the problem in a more thoroughgoing way.

These are very general answers to the how-did-it-get-there question. Occasionally we get more concrete information about problems and solution. For example, some Hollywood stars believed that one side of their faces was more appealing than the other. The stars with the most power could insist on being filmed on their good side, which led directors to make particular staging choices. (Claudette Colbert insisted her left side was her good side, so she’s usually positioned on screen right, with her face turned toward screen left.) David Butler knew that Edward G. Robinson likewise favored his left side, so Butler needed to stage Robinson’s one appearance in It’s a Great Feeling (1949) with him entering a scene from right to left and playing in that position.

One vain star is problem enough, but what happens when you have two who prefer being shot from the same side? According to Henry Koster, the demands of Cary Grant and Loretta Young led to the staging of the scene shown at the top of this section. (For my reservations, see the codicil to this entry.)

The Little Foxes production provides evidence of another very specific problem. In staging the staircase collapse, Wyler faced an unusual difficulty. The actor playing Horace, Herbert Marshall, had a prosthetic leg.

Marshall lost his right leg, from the hip down, in World War I. Through practice he managed to stroll quite smoothly nonetheless, and he became a significant star and featured player in theatre and films. He doesn’t need to walk much in The Little Foxes because his character is rolled around in a wheelchair. But the parlor-and-staircase scene was very demanding. As Wyler explains:

Now there was another problem involved with that, and that was the fact that Herbert Marshall has a wooden leg and couldn’t make the stairs, you see. This is a trade secret. I had him stagger in the background, get behind her and just for a moment when he gets to the stairs he had to go to a landing over there, and just for a moment went out of the picture. And a double came in and went up the stairs, staggered way behind out of focus.

Here you can see Marshall leave the foreground.

An axial cut in to Regina shows him stumbling behind her and going out of shot in the distance. This much Marshall could manage.

At that point the double stumbles into the frame and starts to crawl up the staircase.

Regina leaps up and runs to the rear, and the camera racks focus to the stair, but by now the double’s face is out of frame.

So the director solved the problem of the actor’s disability by a combination of deep staging, the use of a double, and shallow focus. This “trade secret” yielded a range of effects that, I think most viewers would agree, were vivid and exciting.

But there’s always more than one way to do anything. Given the constraint of Marshall’s artificial leg, or a player’s insistence on being shot from one side, or the leading lady’s overnight pimple, a director can work around it in several ways. One of the few critics to notice the implications of Wyler’s choice was Raymond Durgnat, a critic very sensitive to style.

Given a “pimple” or a “wooden leg,” different stylists will find different solutions. One changes the camera-angle; another introduces a last-minute panning shot; another will retain the original set-up, but throw heavy shadows to conceal the offending detail; another will interpose a pot of flowers or a table-cloth to conceal the trouble spot from the camera. The director has ample opportunity to maintain his style in the face of “accident.” And it’s no exaggeration to say that such stylists as Dreyer and Bresson would imperturbably maintain their characteristic style even if the entire cast suddenly turned up with pimples and wooden legs.

I’d add only that the director’s choices are further constrained. Beyond the immediate problem, the broader pressure of norms will kick in. The norms of classical studio lighting, cutting, and performance limit the ways Toland and Wyler can cover up Marshall’s infirmity. The norms of quality A-picture American filmmaking of the period militate against, say, editing the scene so that a dummy is substituted for Marshall on the stair. (We might get that in a serial, though.)

There are also the intrinsic norms set up in The Little Foxes as a formal whole. These favor handling the scene in depth in some way. Wyler reports the decision: “We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.” Wyler’s earlier choices in the film created a kind of path-dependence for this critical moment. Deep-space staging could stay in tune with the rest of the film; but because of his actor’s infirmity, he could give up deep-focus cinematography. This solution created a vivid variant on the film’s intrinsic norm.

You can also argue that by deciding to call our attention to a distant plane in soft focus, Wyler fell back on something he had tried before. In the extraordinary late silent The Shakedown (1929), he showed a pie being stolen in a diner. First, there’s a close-up, then a shot of the main couple looking to the background. In the center, out of focus underneath the coffee urn, the pie is slipping away.

The action isn’t very discernible in my image, which is from a 35mm print; but the scene is shot quite soft anyway. I think audiences notice the gesture, slight as it is, because it’s centered and nothing else is moving in the frame. More visible is the background action in a shot Wyler and Toland used in Dead End (1937). Two gangsters are sitting in a bar debating kidnapping a child. In the out-of-focus background,we can discern a woman wheeling a baby carriage along the sidewalk. She isn’t the target, just a sort of reminder of children’s vulnerability. As in The Little Foxes, a centered background action attracts our attention and makes us strain to identify it.

Faced with a similar problem in The Little Foxes, Wyler had the chance to dramatize a soft-focus background to a much greater extent than in these films.

One more causal factor might have shaped Wyler’s decision. Lillian Hellman’s original play takes place wholly in the Giddens’ parlor and the hallway behind. The play text indicates that the staircase is in the rear of the set, with a landing offstage. The furniture sits downstage, closer to the audience. The foreground/background interaction in Wyler’s staging is already there, in a rougher form, in the play’s set arrangement.

And how does the play handle the moment of Horace’s collapse? When Horace’s medicine bottle breaks, Regina doesn’t move. Calling for Addie the maid, Horace leaves and staggers to the rear playing area.

He makes a sudden, furious spring from the chair to the stairs, taking the first few steps as if he were a desperate runner. Then he slips, gasps, grasps the rail, makes a great effort to reach the landing. When he reaches the landing, he is on his knees. His knees give way, he falls on the landing, out of view. Regina has not turned during his climb up the stairs. Now she waits a second. Then she goes below the landing, speaks up.

REGINA: Horace, Horace.

The foreground/background dynamic, as well as the frozen indifference in Regina’s performance, are written into the scene’s stage directions. Hellman’s instructions yield a further hint: Horace “falls on the landing, out of view.” Within the norms of the deep-focus aesthetic, Wyler and Toland found a cinematic equivalent for this barely-offstage action–one appropriate for their film’s particular style. They make Horace present, but he’s “out of view.”

Somebody may say: “See? You don’t need all this fancy analysis. At bottom, Wyler was forced to shoot the scene this way because of Marshall’s bum leg.” This retort assumes that causal factors always trump functional ones. Instead, I think that by considering causal factors, insofar as we can know them, alongside functional ones, we can better understand filmic creativity in history.

Durgnat’s point shows us how. Even when contingent circumstances “force” a filmmaker to change course, there are always several ways to do that. Picking any option brings in a cascade of other constraints and opportunities. Once Wyler has decided to double Marshall and sustain the take on Davis, soft focus is more or less necessary so we don’t spot the stand-in. But the soft-focus provides a nifty opportunity to create the sorts of functions and effects we’ve already noticed.

Like everybody else, filmmakers choose within constraints—some apparent, some less visible, many just taken for granted. Those constraints limit what can be done, but they also enable other things to happen, perhaps things that the filmmaker couldn’t have planned in advance. Once other filmmakers realize the results, they can plan in advance. A moviemaker today can try out Wyler’s solution, free of the pressures that drove him to it. A significant part of filmmaking’s traditions may consist of workarounds.

The Ostlund epigraph, apparently not available online, is taken from Hollywood Reporter’s December awards issue, p. 13. My Egyptian picture comes from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s called Fish Preparation and Net Making, from the Tomb of Amenhotep (1479-1458 BCE), as rendered by Nina de Garis Davies. I draw the stage directions in The Little Foxes from Lillian Hellman, The Collected Plays (Little, Brown, 1971), 195.

My quotations about It’s a Great Feeling and The Bishop’s Wife come, respectively from two books by Irene Kahn Atkins, David Butler (Scarecrow, 1993), 227; and Henry Koster (Scarecrow, 1987), 87. Koster’s memory fails him in his account of the Bishop’s Wife window scene. It seems likely that Loretta Young favored her left side, which is her dominant orientation throughout the film. But there’s no evidence in the film that Cary Grant favored that side of his face too. The scene at the window is too brief to count as an instance of much of anything.

When I wrote On the History of Film Style in the mid-1990s, I had the nagging memory that Marshall’s artificial leg played a role in Wyler’s staging, but I put it down as legend. (It’s a pity I didn’t pursue it, because the information would have fitted snugly into my sixth chapter.) Only when I discovered a 1972 interview with Wyler, with the “trade secret” mentioned above, did I realize there was something to the story. That interview was once online, but seems to have vanished. It’s available at Columbia University. Durgnat’s discussion is in Films and Feelings (MIT Press, 1967), 41. My other quotations from Wyler come from Axel Madsen, William Wyler (Crowell, 1973), 209.

Otis Ferguson reported on the filming of a different scene in The Little Foxes; I discuss that here. More generally, on the Bazin-Wyler connection, see this entry. Other Wyler-related entries can be canvassed here. For more on Hollywood’s development of deep staging and deep focus, see not only On the History of Film Style but also Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. As for Bette Davis’s eyelids, much in evidence here, there’s this entry.