Archive for the 'Television' Category

So these two English magicians walk into a library …

Kristin here:

Two magicians shall appear in England.

The first shall fear me; the second shall long to behold me;

The first shall be governed by thieves and murderers; the second shall conspire at his own destruction;

The first shall bury his heart in a dark wood beneath the snow, yet still feel its ache;

The second shall see his dearest possession in his enemy’s hand;

The first shall pass his life alone; he shall be his own gaoler;

The second shall tread lonely roads, the storm above his head, seeking a dark tower upon a high hill . . . (John Uskglass, The Raven King, via Vinculus)

A word of explanation about why I am writing about a television series is in order. I write almost entirely about films (and occasionally literature), but in 2001 I succumbed to the temptation of an invitation from Oxford University. I was to become a visiting professor and deliver a lecture series on “broadcast media.” The closest I could come to talking about broadcast media was a series comparing film and television narrative structure. The lectures were subsequently published as Storytelling in Film and Television (Harvard University Press, 2003).

This book has given me a lingering reputation for knowing something about television, even though I had not researched or published on television since. Within the past year I have declined two invitations of speak at television conferences, one of them a keynote address. But until now my small dip in the television-studies pool has remained an aberration.

I happen to be a devoted fan of Susanna Clarke’s 2004 bestselling tale of two magicians in Regency England, Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell. I also, despite some reservations, much enjoyed the recent BBC/BBC America seven-episode adaptation of it. The DVD/Blu-ray is being released in the USA today, and I herewith offer some comments on the series.

My main objections to the adaptation relate to changes in the relationship between the two main characters. I think the reasons for this particular problem can shed a little light on how mainstream film and television narratives are conceived and sold to the public. I’ll deal with that subject first before pointing to some of the things I admire about the series.

Many SPOILERS for both book and series from this point on.

Hanging it on the Amadeus hook

The opening of Robert Altman’s The Player is famous for its pitch phrases heard through studio office windows, with variants of the familiar, it’s X Title meets Y Title (“It’s Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman.” “Not unlike Ghost meets Manchurian Candidate.”) The scene is funny, but it’s not far from the sort of thing that happens in reality.

According to series director Toby Haynes, speaking of the BBC, “I pitched it in my first meeting as Amadeus meets Lord of the Rings. They really responded to that.”

Clearly The Lord of the Rings has nothing in common with JS&MN apart from being a long fantasy tale, and I assume it was included to evoke the idea of a big, really successful example of that genre.

As for Amadeus, at first glance one might consider the book’s Norrell-Strange dynamic as being similar to that of Salieri and Mozart, but upon closer inspection there is virtually no resemblance. Salieri’s prime motivation is intense, heartrending jealousy of Mozart’s seemingly effortless genius. Norrell comes into conflict with Strange, but he’s not jealous of the other magician. The barrier between them is a profound theoretical disagreement over the type of magic they should be doing, and it tears the pair apart after their initial delight in discovering each other. There’s no easy comparison for that sort of conflict, no X meets Y. But anyone can grasp the idea of jealousy.

Once the Amadeus idea was in place, it seems to have guided the filmmakers, at least Haynes and presumably screenwriter Peter Harness, to turn Norrell into Salieri and Strange into Mozart. The effort was not entirely successful, partly because thoroughly changing them would gut the premises of the novel’s plot. Staying at all faithful to the book, as many of the scenes do to a remarkable extent, meant that the motivations for the two main characters’ actions, particularly Norrell’s, became inconsistent.

The Amadeus idea proved useful in publicizing the series. Haynes, Harness, and actors Eddie Marsan (Mr. Norrell) and Bertie Carvel (Jonathan Strange) were probably instructed to try and mention it during interviews. Haynes referred to the “Amadeus meets Lord of the Rings” idea frequently (e.g., here). It’s a catchy phrase, and reviewers and entertainment reporters dutifully spiced up their writings with it. In the Wall Street Journal, John Anderson commented, “The two are, in fact, like Salieri and Mozart in ‘Amadeus,’ had Salieri been a little more talented and a little less poisonous.” Rolling Stone‘s David Fear refers to Haynes’s formula, and fan blogs picked up on it. Google “Amadeus” and “Norrell” to find many more examples.

Although Marsan frequently invoked the Amadeus idea, when interviewed on the BBC’s The One Show, he mentioned another comparison suggested to him by Clarke when she visited the set: “She said they represent the two sides of the brain. The right side of the brain, Norrell, is the analytical side, he’s like the librarian, but Jonathan Strange is the spontaneous, confident, creative side, and it’s the juxtaposition between the two.”

This seems to me a better image for the title characters’ relationship than the Amadeus one: two halves of the same entity, ideally working together in balance. It’s a pity it wasn’t used, but Clarke didn’t mention it until the series was into principal photography.

Norrell is not Salieri

In Clarke’s book, Norrell is far and away the better magician, at least until fairly late in the plot. He certainly has no reason to be professionally jealous of Strange when he appears on the scene, and he doesn’t seem much to care that Strange is more flamboyant and socially adept.

The series often suggests, however, that Norrell is the inferior magician. The second episode’s opening depicts his ship illusions at the port of Brest during the first Napoleonic war. Seemingly the French are fooled for only the time it takes some officers to row out and investigate them. Norrell’s illusion seems ineffectual, and one might wonder why in the next scene Parliament is so enthusiastically applauding him and promising all sorts of cooperation in exchange for his help. This, I would suggest, is one of several plot holes resulting from the makers’ devotion to the Amadeus model.

In the book, the ship illusion is highly effective. Not only Brest but “Rochefort, Toulon, Marseilles, Genoa, Venice, Flushing, Lorient, Antwerp and a hundred other towns of lesser importance” are blockaded by Norrell’s ships.

Everyone, it seemed, was delighted with what Mr Norrell had done. A large part of the French Navy had been tricked into remaining in its ports for eleven days and during that time the British had been at liberty to sail about the the Bay of Biscay, the English Channel and the German Sea, just as it pleased and a great many things had been accomplished. (p. 108)

This triumph leads to a successful ten-year career. Although Strange is the one who aids Wellington at the front lines using magic, Norrell contributes in other ways. After the victory at Waterloo, “Mr. Norrell had the satisfaction of hearing from everyone that magic–his magic and Mr Strange’s–had been of vital importance in achieving this.” (p. 337) He then goes into the respectable business of dealing with commissions such as flood control for the Admiralty.

The TV series also presents Norrell’s system for protecting England’s southern coast as a failure, never completed and ineffectual where it did exist. Directly after he installs the system, its faults are apparently revealed when a ship goes aground on a shoal near the same beach, a situation solved by Strange with his flashy creation of giant sand horses. In the book, Strange collaborates on the coastal protection project alongside Norrell. It is installed nearly a decade after the “Horse Sands” episode and works very well. Indeed, the Admiralty finds Norrell so useful that he cannot deal with all the projects they propose to him, especially since he refuses to take on students after Strange leaves him.

Thus unlike Salieri, Norrell’s problem is not inferior talent but an inability to excite others about his magic. He is, as Clarke makes clear over and over, boring. An odd trait in a book’s protagonist, or co-protagonist in this case, but one that she manages to make entertaining. The novel describes Norrell’s first visit to Sir Walter Pole and his attempt to explain his feat of having brought the statues of York Minster to life: “Curiously, though Mr Norrell was able to work feats of the most breath-taking wonder, he was only able to describe them in his usual dry manner, so that Sir Walter was left with the impression that the spectacle of half a thousand stone figures in York Cathedral all speaking together had been rather a dull affair and that he had been fortunate in being elsewhere at the time.” (p. 68)

Even at the end of the ten years, Norrell remains clueless about public relations. Late in the book he and Lascelles go to Brighton to check the new coastal protection system:

“It is invisible,” said Lascelles.

“Invisible, yes!” agreed Mr Norrell, eagerly, “But no less efficacious for that! It will protect the cliffs from erosion, people’s houses from storm, livestock from being swept away and it will capsize any enemies of Britain who attempt to land.”

“But could you not have placed beacons at regular intervals to remind people that the magic wall is there? Burning flames hovering mysteriously over the face of the waters? Pillars shaped out of sea-water? Something of that sort?”

“Oh!” said Mr Norrell. “To be sure! I could create the magical illusions you mention. They are not at all difficult to do, but you must understand that they would be purely ornamental. They would not strengthen the magic in any way whatsoever. They would have no practical effect.”

“Their effect,” said Lascelles, severely, “would be to stand as a constant reminder to every onlooker of the works of the great Mr Norrell. They would let the British people know that you are still the Defender of the Nation, eternally vigilant, watching over them while they go about their business. It would be worth ten, twenty articles in the Reviews.”

“Indeed?” said Mr Norrell. He promised that in future he would always bear in mind the necessity of doing magic to excite the public imagination. (p. 688)

The fact that many of Norrell’s commissions are designed to prevent things from happening also means that the public forgets about them. This scene demonstrates well how Clarke manages to generate amusement out of a character who is so intrinsically dull.

The Norrell we see in the first two episodes of the series is fairly similar to the one in the book–naive, petty, anti-social, and arrogant. His first act in both versions is to twit aspiring magician John Segundus about having read his article on magician Martin Pale’s fairy servants and noticed that he had left one out. He then lets it sink in that he himself owns the only copy of the only book that mentions that servant and thus Segundus could not possibly have read about him.

Despite his faults, however, Norrell is frequently amusing, something the series captures well, especially in the opening episodes. He also arouses our pity when he visits Sir Walter Pole to volunteer his help in the war with Napoleon and is summarily dismissed.

Unfortunately, starting with the third episode the makers abruptly change Norrell’s character, making him more devious and villainous. One reviewer commented on this change:

It’s ridiculously difficult to make you feel a sense of loathing for an actor like Eddie Marsan, but Strange and Norrell went a long way in making you feel like that this week. It’s kind of amazing in such a short space of time how the show has managed to make you feel for Norrell’s plight to restore magic to England, to suddenly very much wondering if that was a good idea.

The reviewer hints that the series has accomplished this change well, but the inconsistency of Norrell’s character continues in later episodes. As he also suggests, it is really Marsan’s splendid performance that manages to make all this hang together.

In the book Norrell does some nasty things, though not nearly so many or so bad as what we see him do in the series. In the novel he neither tries to intimidate Lady Pole into silence nor threatens Drawlight with torture to make him go to Venice to find Strange. He does not accompany Strange to see George III, because he is genuinely convinced from the start that magic cannot cure his madness. When he makes Strange’s book disappear, he offers to pay the publisher’s costs for the entire edition. (He also leaves Strange’s own copy untouched.) He does not berate Childermass for being unconscious for four days after taking a bullet for him. Lady Pole does not create a tapestry in an effort to reveal her situation to Arabella, and hence Norrell doesn’t order it stolen. He never threatens to destroy the other magician, as he is shown doing at the end of episode 4.

His primary mistake, in both versions, is that through shame and fear he hides the fact that he had violated his own principles by summoning the gentleman with the thistle-down hair to resurrect Lady Pole. (The fairy is referred to as the gentleman with the thistle-down hair throughout the book and simply as the Gentleman in the series.) Had he found the courage to tell at least Strange the truth, it might have made him less eager to try contacting a fairy to help him with his own magic.

Norrell does none of these things through jealousy.

Strange is not Mozart

Strange is portrayed as the Mozart to Norrell’s Salieri. He does magic spontaneously rather than learning spells out of books. In the scene where he first demonstrates his magic for Norrell, he says, “One has a sensation like music playing at the back of one’s head–one simply knows what the next note will be,” (p. 233) a line changed slightly for the series. The obvious similarity of this statement to Mozart’s effortless ability to write heavenly music probably sparked the initial link in the makers’ minds between JS&MN and Amadeus. It no doubt influenced Harness to portray Strange simply as a natural genius. Yet the book makes it clear that Strange’s moments of inspiration often either turn out wrong or he simply cannot replicate or reverse them.

For example, the “Horse Sands” episode, so crucial for the series’ creation of the idea of Norrell’s inferiority and jealousy, turns out quite differently in the book. Strange’s sand horses do free the ship from the shoal, but “These did not just disappear when their work was done, as Strange had said they would; instead they swam about Spithead for a day and a half, after which they lay down and became sandbanks in new and entirely unexpected places. The masters and pilots of Portsmouth complained to the port-admiral that Strange had permanently altered the channels and shoals in Spithead so that they Navy would now have all the expense and trouble of taking soundings and surveying the anchorage again.” (p. 278)

The feat impresses the Ministers in London, however, leading them to dispatch Strange to Portugal to help with the war. There Strange’s first successful piece of magic, building a road, is managed through a spell derived from one of Norrell’s books. It’s the same sort of respectable task with which Norrell continues his own success. Later, though, Strange performs ancient, black magic to bring to life some Neapolitan corpses to supply vital intelligence information to Wellington. Norrell refuses to bring rotted bodies to life, but Strange tackles decaying, maggot-ridden ones. The series’ scenes of this episode (above) well convey the horror Strange feels after he succeeds. One of the most effective shots in the series is the long view of the troops, including Strange, moving out of the camp toward victory with the burning windmill in which Wellington has had the zombies locked appearing prominently in the composition (see top).

This parallel to Norrell’s raising of Lady Pole is usually not remarked upon, but it suggests that both have compromised their principles in somewhat similar ways to gain respect and aid the war effort.

Undoubtedly more important, in the book Strange never becomes obsessed with bringing Arabella back to life after the Gentleman tricks him with the moss-oak double of her. Instead he goes immediately to Venice to grieve and to try and summon a fairy to teach him magic and become his servant. He does this solely because he thinks that fairy magic, long gone from England, is an exciting alternative to Norrell’s stodgy, respectable magic. Clearly the plot additions of Strange desperately seeking to revivify his wife and Norrell’s cold refusal to answer his letters or explain how he resurrected Lady Pole were added to heighten the dramatic conflict between the two.

Friendly Enemies

Yet that conflict is for the most part a half-hearted one and fated to end. It is quite different from what happens in Amadeus. Salieri hates Mozart and vows early on to destroy him, while Mozart is largely indifferent to Salieri. In contrast, Norrell and Strange have an immediate affinity that never completely disappears, and they grow more and more like each other in the course of the book. The abrupt change in Norrell’s initial skeptical, fearful attitude toward the second magician comes during their second meeting (their first meeting in the series), when Strange performs magic for him. “Mr. Norrell, who had lived all his life in fear of one day discovering a rival, had finally seen another man’s magic, and far from being crushed by the sight, found himself elated by it.” (p. 233) This elation is wonderfully conveyed by Marsan in one of the series’ best scenes (above).

Contrast this moment with the scene of Mozart’s meeting Salieri, where Mozart humiliates Salieri by playing his little welcoming march and improvising a far better piece from it. This leads directly to Salieri’s vow to God that he will destroy Mozart, ultimately leading to the latter’s death (see first section above).

In the series’ next scene, Norrell’s delight continues as he meets with Strange to plan their studies. He even manages, with some difficulty, to hand over a book that he wishes his pupil to read. Thereafter, unfortunately, we get very little of the two interacting, and the viewer might get the impression that their break occurs a short time later. After seeing only two episodes, Anibundel, a blogger and fan of the book pinpointed the problem:

Though Bertie Carvel and Eddie Marsan are magic together, there was no getting around it–they weren’t together for nearly long enough. The complex nature of their relationship–being pulled towards each other while at the same time repelled by their philosophical differences–is the heart of the novel, and by the show deciding to spend their energies focused elsewhere makes it feel like they’re missing the nut of the story in order to let us indulge in the trimmings. Strange barely became Norrell’s pupil, and barely had time to note how much his teacher held back from him. We barely got any of Norrell’s excitement and joy at discovering someone who he can really talk to and connect with most emotionally and intellectually, before the show already separated them again, putting Strange on his way to Portugal.

Part of the problem is that the adaptation conveys little indication of how much time passes. In the novel, Clarke simply dates every chapter. We know that the precipitating action of John Segundus and Mr. Honeyfoot visiting Mr. Norrell happens in the autumn of 1806 and the final scene in Padua in the spring of 1817. The adapters would have done well to employ superimposed titles for the same purpose. As it is, even non-readers who know the era of the Napoleonic wars and Regency England pretty well would be hard put to estimate that the action covers that long a span.

In the book Strange becomes Norrell’s pupil in September, 1809 and parts ways with him in February, 1815. His first wartime stint lasts for a little over three years, from approximately March, 1811 to May, 1814. The second begins in June of 1815, after the two split. Thus he studies with Norrell for a little under two and a half years.

During that period, Strange temporarily takes the place of the devious Drawlight and Lascelles in assisting his teacher:

In the past year Mr Norrell had grown to reply a great deal upon his pupil. He consulted Strange upon all those matters which in bygone days had been referred to Drawlight and Lascelles. Mr. Norrell talked of nothing but Mr Strange when Strange was away, and talked to no one but Strange when Strange was present. His feelings of attachment seemed all the stronger for being entirely new; he had never felt truly comfortable in any one’s society before. (p. 279)

Nevertheless, the one issue that drives the pair apart is their stark disagreement concerning the desirability of using modern, respectable magic or calling upon the 300-year-old, wild magic of the Raven King and fairies. Their disagreement comes to a head when Strange writes his lacerating review of the book about Norrell and arrives to announce that he will no longer be his pupil. In the book, far from arguing with Strange or berating him over the review as in the series, Norrell is entirely conciliatory and emphasizes their affinity in a conversation which is perhaps the most important summary of their relationship.

“You think that I am angry,” said Mr Norrell, “but I am not. You think I do not know why you have done what you have done, but I do. You think you have put all your heart into that writing and that every one in England now understands you. What do they understand? Nothing. I understood you before you wrote a word.” He paused and his face worked as if he were struggling to say something that lay very deep inside him. “What you wrote, you wrote for me. For me alone.”

Strange opened his mouth to protest at this surprising conclusion. But upon consideration he realized it was probably true. He was silent. (p. 417)

Norrell then makes a revelatory confession that as a young man he, too, had been obsessed with the Raven King and spent ten years trying to contact him. His failure led to a traumatic disillusionment and a rejection of old magic. This, of course, explains a great deal about his character, and it is odd that the screenwriter avoided it so entirely. In the series, Strange simply insists that that they are too different in their views to continue together. Much of the emotional dialogue spoken beside the fireplace comes only from the last section of this important conversation in the book, leaving out the parts quoted above.

“Oh,” cried Mr Norrell, “I know that in character . . .” He made a gesture of dismissal. “But what does that matter? We are magicians. That is the beginning and end of me and the beginning and end of you. It is all that either of us cares about. If you leave this house today and pursue you own course, who will you talk to? –as we are talking now?–there is no one. You will be quite alone.” In a tone almost of pleading, he whispered, “Do not do this!” (p. 421)

He also offers Strange the things he offers in the TV scene, including an equal partnership and the key to the library at Hurtfew, and he says he will not demand that the review be retracted. Strange nevertheless insists on ending their relationship.

Even so, in the novel he somewhat regrets his decision the next day: “As a consequence of what Mr Norrell had said he had developed a great many new ideas about John Uskglass, and now he was suffering all the misery of having no one to tell them to.” (p. 423) This misery, however, is not sufficient to make him return to Norrell.

From this point the two are separated, but in the novel there are indications that they are destined to reunite. Much later, Strange, with a mad expression, sends Drawlight to tell Norrell “I am coming!” As in the series, Norrell rushes from London to Hurtfew Abbey to defend his main library from attack. At this point, the narration describes a slightly eerie discovery recently made by Norrell.

Ever since he and Strange had parted he had been in the habit of summoning up visions to try and discover what Strange was doing. But he had never succeeded. One night, about four weeks ago, he had not been able to sleep. He had got up and performed the magic. The vision had not been very distinct, but he had seen a magician in the darkness, doing magic. He had congratulated himself on penetrating Strange’s counterspells at last; until it occurred to him that he was looking at a vision of himself in his own library. He had tried again. He had varied the spells. He named Strange in different ways. It did not matter. He was forced to conclude that English magic could no longer tell the difference between himself and Strange. (p. 713)

In the book Norrell later surmises that he and Strange are both trapped in the Darkness, a curse designed for Strange alone, because the Gentleman had been so imprecise as to direct the curse at “the English magician.” (p. 749) That same imprecision occurs in the spell devised by the two and intended to summon the Raven King. They address the spell to the “nameless slave,” allowing Stephen, rather than the Raven King to gain the power necessary for him the kill the Gentleman and take his place.

Mr Norrell with the candlestick in the library?

I’m not sure what viewers unfamiliar with the book would expect to happen when in the final episode Norrell solves Strange’s labyrinth and reaches the library. Given how badly Norrell has acted at times and also given Strange’s madness, they could reasonably expect a big fight in which Strange might kill Norrell or at least triumph over him. Indeed, in the book this is what the servants and Lascelles, locked out of the labyrinth, imagine might happen: “Images of magical battles flitted through the minds of everyone present: Mr Norrell hurling mystical cannonballs at strange; Strange calling up devils to come and carry Mr Norrell away. They listened for sounds of a struggle. There were none.” (p. 721)

In the book there is no fight at all. Norrell, terrified of what Strange intends to do to him, finds the other magician reading historical accounts of fairies kidnapping humans. Strange’s first comment to his former teacher is a compliment.

“I like your labyrinth,” he said conversationally. “Did you use Hickman?”

“What? No. De Chepe.”

“De Chepe! Really?” For the first time Strange looked directly at his master. “I had always supposed him to be a very minor scholar without an original thought in his head.”

Relieved that Strange is not going to attack him, Norrell gives him a mini-lecture on De Chepe, and they quickly slip back to their old relationship. Norrell returns Strange’s compliment.

“You own labyrinth was quite remarkable,” said Mr Norrell. “I have been half the night trying to escape it.”

“Oh, I did what I usually do in such circumstances,” said Strange carelessly. “I copied you and added some refinements. (p. 741)

Later in the scene, the roles are reversed. Strange requires a summoning spell, and Norrell fetches a sheet of paper from a drawer and gives it to him, saying it is the best such spell he knows. It is written in Norrell’s hand and labeled “Mr Strange’s spell of summoning.” Norrell pedantically points out three changes he has made, including “I have omitted the florilegium which you copied word for word from Ormskirk. I have as you know, no opinion of florilegia in general and this one seems particularly nonsensical.”

“It is as much your work as mine now,” observed Strange. There was no trace of rivalry or resentment in his voice.

“No, no,” said Norrell. “All the fabric of it is yours. I have merely neatened the edges.”

The two are at last capable of adapting each others’ work as equals. Far from having a physical fight, they don’t even argue. Instead, they work together to devise and implement the spells that create the climactic resolution.

Again, contrast this with the climactic scene of Amadeus, where Salieri takes dictation from Mozart. He not only cannot keep up, but he is also baffled by some of the choices Mozart makes in composing the Requiem. There remains no affinity between the two.

The two magicians’ reunion in the library is where the series’ final episode goes thoroughly off the rails, in my opinion, departing from the book and introducing all sorts of new premises and actions that make little coherent sense. The departure begins at 16:30, to be precise, when Norrell throws something (the candlestick, I think) at Strange and their brief struggle ensues. David, being my test case of a non-reader viewing this part, said he had followed the story reasonably well to then but after that point he suddenly didn’t understand the rules. Quite.

I will not attempt to list all the peculiar premises suddenly introduced into the story. In brief, how does Strange know that the Gentleman has closed the King’s Roads to him? How does Norrell know that the rule doesn’t apply to him as well? Norrell’s speech about the Gentleman’s “alliances with the forces of nature within the Christian world, our world, not his–ergo, his curse will not affect us here” baffles me. Why does the darkness not follow the pair into Faerie? As far as I can tell from the book, it is itself a part of Faerie. And why has the series added the premise that Strange is dying under the continued influence of being in the Darkness? (Screenwriters seem to love such ideas. It reminds me of the absurd premise in The Return of the King that Arwen is dying because her fate is linked to the Ring. Aren’t all of their fates?) The Gentleman’s taste in revenge is not for death but for perpetual misery.

Certainly by this point the Amadeus comparison has been abandoned. But why were the makers so determined to pursue that idea in the first place? Once they had used the analogy in order to get a greenlight for the project, why did they not simply drop it and take the book as their guide? Perhaps in part because once they had posited that the Salieri-Mozart conflict is similar to the Norrell-Strange one in Clarke’s book, they had fixed that in their minds and couldn’t see it any other way. But we return to the fact that the Amadeus premise is simply easier to understand than the very complex dynamic between the two magicians in Clarke’s book. Once the hook of the Amadeus comparison got out into the public through reviews and interviews, the audience could have a simple interpretive key even before watching the premiere. A bitter conflict is more dramatic than a complex competition/cooperation dynamic between two protagonists, a dynamic based on a fundamental theoretical disagreement.

And why not, after all? What difference does it make that the series’ makers battened onto Amadeus and went with it? Might it not make it easier for viewers to cope with a very complicated story?

Perhaps. Still, a considerable price is paid in the loss of originality. Clarke’s book is very good, possibly great, in part because the shifting relations between its title characters are so slippery, with both of them having many faults and vastly different views of magic but nevertheless by the end belonging together as partners. The TV series ultimately settles instead for a well-known formula from a classic, familiar film. For lovers of the book, the core fan-base for the series, disappointment in at least some aspects of the series was likely.

Perhaps more important, however, is the loss of unity. The sudden changes in Norrell’s character that I’ve pointed out are among these. I would think that, after Norrell’s more villainous moments, the viewer might reasonably be puzzled by the cheery, cuddly reunion between the two, with Strange buttoning up Norrell’s cloak (see the “Norrell is not Salieri” section above) and promising to come to breakfast. Similarly, the sudden deep emotion of the scene where Strange breaks with Norrell might seem odd. I expect that Norrell’s misdeeds caused some non-readers to mistake him for the villain, though the Gentleman clearly should centrally occupy that role. The messiness of the final episode comes in part because the two must reconcile and work together so abruptly, despite all of Norrell’s misdeeds. Finally, I think the emotional appeal of the main relationship between the two magicians, which is the core of the novel, is vitiated to some extent.

Two super-magicians and their flying library

There may also be one more reason why Norrell is made villainous in the central section of the story and then comic at the very end. The makers possibly wanted to avoid using the original, highly unconventional ending of the book, perhaps feeling felt that spectators would not accept it.

The novel sets us up for the idea that the Darkness may not be such a bad thing. Immediately after Norrell discovers that Lady Pole and Mrs Strange are no longer in Faerie, he also realizes that the curse of Darkness has not lifted. Naturally he considers this in a rational fashion.

This then was his destiny!–a destiny full of fear, horror and desolation! He sat patiently for a few moments in expectation of falling prey to some or all of these terrible emotions, but was forced to conclude that he felt none of them. Indeed, what seemed remarkable to him now were the long years he had spent in London, away from his library, at the beck and call of the Ministers and the Admirals. He wondered how he had borne it. (p. 770)

The book’s final scene occurs about two or three months after the climactic events. Strange and Norrell travel to Italy together, in Hurtfew Abbey and conveyed by the Darkness. How they do this is not explained, but clearly they have quickly learned to live with and even to control the conditions of the Gentleman’s curse. Arabella is living in Padua with Flora Greysteel and her father, friends Strange had made during his time in Venice. She meets Strange for the first time since their brief reunion in Lost-hope. Naturally she asks him, “Have you found any thing yet to dispel the Darkness?”

His insouciant response is miles away from what we might expect: “No, not yet. Though, to own the truth, we have been so busy recently–some new conjectures concerning naiads–that we have scarcely had time to apply ourselves to the problem. But there are one or two things in Goubert’s Gatekeeper of Apollo which look promising. We are optimistic.” He goes on to describe the pair traveling around the world in the Darkness: “Who is to say that the Darkness may not be an advantage. We intend to go out of England and are likely to meet with all sorts of tricksy persons. An English magician is an impressive thing. Two English magicians are, I suppose, twice as impressive–but when those two English magician are shrouded in an Impenetrable Darkness–ah, well! That, I should think, is enough to strike terror into the heart of any one short of a demi-god!”

Although Strange does reassure Arabella that he and Norrell will keep trying to end the Darkness curse, he seems more enthusiastic about traveling with Norrell and having unspecified kinds of adventures. Indeed, the two magicians are still tethered together invisibly, with Norrell of necessity waiting nearby during the conversation, no doubt reading a book. Norrell, poor traveler though he is, can do all this quite comfortably because, as Strange explains, “He need never leave the house if he does not wish it. The world–all worlds–will come to us.” (pp. 781-82)

Lest we worry that Strange is caddishly deserting a weeping Arabella, Clarke sets up for the final scene by making it clear that Mrs Strange has grown tired of the stresses of life with a magician. When Flora remarks that it is “very odd that he should have gone back to his old master at last,” Arabella replies, “Is it? There seems nothing very extraordinary in it to me. I never thought the quarrel would last as long as it did. I thought they would have been friends again by the end of the first month.”

Flora objects that Norrell had attacked Strange in the magical journals. Arabella gives a reply that echoes Norrell’s speech to Strange in the parting scene.

“Oh, I dare say!” said Arabella, entirely unimpressed. “But that was just their nonsense! They are both as stubborn as Old Scratch. I have no cause to love Mr Norrell–far from it. But I know this about him: he is a magician first and everything else second–and Jonathan is the same. Books and magic are all either of them really cares about. No one else understands the subject as they do–and so, you see, it is only natural that they should like to be together.”

She has gradually settled into a pleasant social and domestic life in Padua with Flora and her father: “Of her absent husband she thought very little, except to be grateful for his consideration in placing her with the Greysteels.” (pp. 779-80) No wonder she takes Strange’s startling news about his and Norrell’s plans so calmly.

Strange and Norrell’s final design for living is not the conventional romantic ending that we surely expect, with husband and wife reunited, living happily in Shropshire and occasionally visiting Norrell. Intellectual debate and the lure of further adventures, for once, carry the day. Whether audiences would have been seriously upset at such an outcome is unclear. It would have been worth a try, I think. The series’ scene of Strange appearing to Arabella as a reflection in a well and telling her he loves her is schmaltzy and, to me at least, unsatisfactory as closure.

The series ends with Childermass and Vinculus visiting the newly re-instituted Learned Society of York Magicians (a scene which in the book precedes the Strange-Arabella conversation). The Society now consists mainly of Strangites and Norrellites. Childermass suggests to the group that Strange and Norrell are caught in some unknown place “Behind the sky. On the other side of the rain.” (p. 778) He hints that the new writings on Vinculus, if they can be deciphered, might affect the two magicians’ fates–perhaps implying that they could be rescued from the mysterious limbo in the sky into which the Darkness sucks them. Given how few rules we have been given about the Darkness, this is more vague than pleasantly ambiguous.

All the books in the world

I mentioned at the beginning that I have very much enjoyed the series, having now watched it straight through twice and gone through again making notes and taking frames for this entry. Putting aside my complaints, I would like to mention some things that I particularly like about it.

In order to inveigle David into watching the series with me, I told him that it was basically about books. Seeing it again, I realized that I did not really exaggerate. Both the causal action and the characterizations depend heavily on books, and there is also just the sheer sensuous pleasure of the beautiful rare books and the libraries they reside in. Both Clarke’s book and the series are beloved of bibliophiles. The novel is famous for its many footnotes, many of which refer to obscure (and fictitious) books of magic, most importantly Jacques Belasis’ Instructions (date unknown), a frequent reference for both Norrell and Strange, and Thomas Lanchester’s Treatise concerning the Language of Birds (16th Century). One scene in the series, the book auction, is loosely derived from a footnote (#5, pp. 283-84)

Most of the important male characters in both book and series are characterized by their relations to books. Norrell’s manipulative power and selfishness comes through books, though he clearly loves them in and of themselves. They have essentially replaced human interaction for him. A poignant little moment comes after Norrell agrees to send forty books with Strange on his wartime journey. He does not make an angry speech to Childermass about regretting having come to London, as happens in the series; that speech is actually derived from a description of Norrell’s sad thoughts over dinner.

He wished he had never come to London. He wished he had never undertaken to revive English magic. He wished he had stayed at Hurtfew Abbey, reading and doing magic for his own pleasure. None of it, he thought was worth the loss of forty books.

After Lord Liverpool and Strange had gone he went to the library to look at the forty books and hold them and treasure them while he could. (p. 287)

In the novel, the forty books get quite battered, but they are not destroyed, there being no such scene as the battle in the forest. Indeed, Jeremy Johns, Strange’s servant and book porter, also survives the war. I couldn’t find a mention of Strange returning Norrell’s books, but presumably he does.

The other characters are also defined to a considerable extent by their relationship to books and other publications. Although Strange is often taken to be a “natural” magician needing no training, he greatly desires to have access to Mr. Norrell’s library, knowing full well that he often cannot replicate or reverse his own spells. Lascelles in effect controls Norrell’s PR by managing the authorized publications. Childermass is a frustrated aspiring magician held back by his working-class status in Norrell’s household, and he surreptitiously reads the books in the library. Segundus and Honeyfoot’s sincere desire to learn magic, or at least read about it, marks them as the humble helper figures. Although Stephen is not directly associated with books, he has had an excellent education that has gained him no respect because he is black. The Gentleman, on the other hand, has nothing but scorn for learning magic through books. When Norrell tells him that he has taught himself magic, his response is a contemptuous “Books!” Being a fairy, he assumes that magical abilities can only be taught by a master. He twice presses his services as a teacher upon Norrell, who has such a hatred for fairy magic that he indignantly declines and thus gains the enmity of the Gentleman.

The street magician Vinculus is the embodiment of fairy-derived magic, carrying the book of the Raven King written in tattoo-fashion upon his body. Although he cannot read himself as a book, he has in his memory the prophesies of the Raven King, and he delivers them to predict and presumably guide the fates of Norrell, Strange, and Stephen.

Books are central to the causal anatomy of the plot. They permit such things as the relatively inexperienced Strange’s successes in his wartime service, including the magical construction of the road, which convinces the skeptical Duke of Wellington that magic might have military advantages after all. Norrell’s suppression of Strange’s book leads to suspense over whether Strange will take a violent revenge on him. The two successive texts written on Vinculus have a function that is difficult to pin down, but perhaps we are to assume that it consists of the magic that governs all the rest of the action. As Vinculus tells Childermass, in both novel and series, Norrell and Strange “are the spell John Uskglass is doing. That is all they have ever been. And he is doing it now!” (p. 758).

The series keeps books in the forefront as a general motif. Most obviously, Norrell’s bibliophilia is used to counter the more villainous aspects of his character added by the adapters. He remains a charming character in part through little bits of book-related business and dialogue. Norrell’s attempt to escape the crowd at Lady Godesdone’s party leads him to discover some books in a side room; he appreciatively, even lovingly, sniffs the book before he starts reading, a detail not in Clarke’s novel.

There is a similar moment more difficult to notice. In the first teaching session, Norrell emphasizes respectable magic and moves to fetch a book. He gives a large rolling staircase a push and steps onto it while it is moving; it stops exactly by the book on the top shelf that he is after (above).

There are other such moments. When Norrell hears Lucas, his footman, handling some books, he detects carelessness and calls out, “Mind the spines, Lucas! The spines!” His desire to acquire a specific volume at auction is emphasized by his petulant remark, “I’ve been looking for that book for years.” How many of us could not sympathize with that? Finally, there is Norrell’s exclamation during his ecstatic reaction to Strange’s spell: “It is not in Sutton-Grove!” Francis Sutton-Grove’s De Generibus Artium Magicarum Anglorum, 1741, classifies 38,945 areas of magic. It is “reputed to be the dreariest book in the canon of England Magic.” Mr Norrell is “Sutton-Grove’s greatest (and indeed only) admirer.” (Footnote 6, p. 59).

All this is why I think the adapters made a serious mistake in having Strange demand that Norrell sacrifice his entire library to provide the handsel for their final spell. Nothing of the sort happens in the novels. At one stage in the proceedings, all of the books briefly turn into ravens and swirl around the room, but they all turn back. There is no logic to having Norrell’s books offered to the Raven King. Why offer “all of English magic” to him? He embodies English magic, and he surely has no use for books. I suspect that this peculiar idea was added to allow the cheap humor of Norrell’s trying to bargain Strange into to taking only half of his library, or at most two-thirds. I can’t see a necessary function for it. The idea of the library being lost like this surely sent chills through fans and bibliophiles everywhere.

Like a film

I often read about a television series that has been made in the style of a film. Again, I don’t see much television, but I had to this point not seen one that does look like a film. But JS&MN does, much of the time. Given its comparatively limited budget compared to a typical historical epic of this type, it’s very impressive in its design (see bottom, for example) and cinematography (as in the top image, with its suggestion of a Turner landscape). The digital matte shots in the special effects are usually obvious as such, but they give the images an old-fashioned look that somehow seems appropriate.

At times Toby Haynes’s direction reminded me a bit of Spielberg’s, in that he has a similar habit of varying his setups within scenes. Clearly each separate framing is chosen for a specific action, as with Spielberg. These six framings open the scene in which Strange visits Norrell for the first time, and the sequence as a whole continues in this way throughout, with few repeated setups. The choice of framings manages to focus on the conversation between Stange and Lascelles while keeping us aware that Norrell is nearby, torn between suspecting that Strange is a fake and fearing that he is a rival.

To keep with the Amadeus theme, the series frequently contains too many shots. Do we really need four separate images of Vinculus reading the titles of the spells he has stolen from Childermass? Still, Haynes has the good sense to keep his camera on a tripod most of the time, though he is overly fond of push-ins.

One device that particularly impresses me is the systematic use of planimetric shots to characterize Norrell. This begins in the scene where he tries to interest the politician Sir Walter Pole in using his magic in the war effort and Pole humiliatingly rejects him (top of this section). It becomes more complex, though, in the beach scene where Norrell underwhelms the onlookers by silently installing his invisible beacons. This episode is presumably inspired by the scene in the book, quoted above, where Lascelles chides Norrell for not adding impressive visual elements to his coastal protections.

It begins with a crane down from the distant onlookers to Norrell inaudibly muttering his spell. For a time, variant shots of him against the empty seascape alternate with framings of Strange looking on with increasing doubt and Sir Walter chatting to Arabella about the dire situation of the war. Arabella holds her binoculars ready, expecting to see something appear.

Norrell has clearly been prepared for the occasion by Drawlight and Lascelles. He wears a new, expensive-looking outfit, and he seems to remember being told to gesture impressively. He raises his hands for a lackluster flourish, looking none too confident, and turns to the crowd, announcing, “It is done.” Arabella and Pole look surprised, as Norrell continues, off, “The sea defenses are now in place.”

In a shot of the onlookers, Lord Liverpool calls out, “I cannot see anything!” In medium close-up, Strange reacts, and Norrell, off, says “You will not see anything. They are invisible.” In long shot, Norrell looks out to sea and insists, “It is done.”

As Drawlight tries to arouse some enthusiasm by cheering for Norrell, there is a transition to a new section of the scene. An oblique view shows Norrell rejoining the group. Strange moves toward the sea and Sir Walter follows him. A planimetric shot of the pair, taken in profile rather than straight onto or away from the sea, contrasts with the earlier part of the sequence. As Norrell and the others watch them chatting, Sir Walter and Strange are shown in two variant framings from behind. While the horizon line had hovered just above Norrell’s head, the hats of these two reach the horizon in one view and slight break through it in the second. They do not look as small and ineffectual as Norrell had against the seascape.

Finally, after declaring that he dislikes Portsmouth intensely, Norrell trudges away toward screen right while Strange and Sir Walter remain looking leftward out to sea on the other. The visual style conveys both the humor and pathos underlying the shifting fortunes of the two magicians.

Other scenes use planimetric shots less extensively, including Norrell’s escape from the crowd at the party and several framings in the two magicians’ visit to George III, in some of which Norrell’s figure is again overwhelmed by his surroundings. (See also the bottom image.)

Others include his visit to Lady Pole, the magicians’ reunion after the war (see Friendly Enemies section), and their final parting.

After the latter scene, the planimetric framings disappear. I suppose this is because once the two part, there is less necessity to play create contrasts between the magicians.

Too challenging for BBC Sundays?

Why was the series relatively unsuccessful? Apparently viewership in England started off high but dropped precipitously thereafter. I don’t think the quality of the production can be blamed. Gerald O’Donovan praised the series in the Telegraph and wrote that it did not deserve such a fate. He suggests that it “was just too odd and convoluted to appear to the Sunday night mainstream. It should be interesting to see whether it lives on and wins further fans via the more cult-friendly media of boxed sets and online streaming.”

O’Donovan’s diagnosis is probably correct. Even considerably compressed, the thing was just too complicated for people to follow. The episodes move at a relentless pace. Episode 2, though perhaps the best in the series, in particular crams a surprising amount of the book’s narrative material into its approximately 50-minute running time. There is little time for redundancy in the presentation of causal material.

For example, everyone can grasp the scene in which Strange reveals to Arabella that he has become a magician and proves it by doing a spell with a mirror that allows him to see a different room, occupied by a man he doesn’t know but whom we recognize as Norrell. Most will understand that this is one of the two spells Strange bought from Vinculus after the latter recited the prophecy about two magicians (see top). But where did Vinculus get the spells, and who wrote them originally?

They were written by Norrell in an earlier scene, where he gave them to Childermass as an aid to getting Vinculus to leave London. He orders Childermass not to use them unless necessary, and Childermass never gets the chance, since Vinculus steals them out of his pocket.

It’s not absolutely necessary that we grasp this connection between the two magicians, who do not yet know each other’s identities. But it is helpful at least to understand that Norrell writes simple spells because he has only allowed Childermass to learn a limited amount of magic, and thus even Strange, who has never done magic before, can successfully use “One Spell to Discover what My Enemy is doing Presently.”

There are many connections that I failed to notice on the first time through and picked up on the second viewing. I can only imagine how people who have not read the book can follow much of the action. (After one viewing, David had no idea that Norrell had written Strange’s spell, and I think it is safe to say that he is pretty good on narrative.)

Another possible puzzler is the frequent reference to “Christians.” Clarke explains that this is what fairies call all mortal creatures; the series doesn’t. It’s a subtle point, but it explains why the tales that Lady Pole tells when she tries explain her enchantment all refer to characters and even animals as Christians. As Mr. Honeyfoot points out, these stories are told from the points of view of fairies.

As O’Donovan says, another probable obstacle has been that the series, however much it has conventionalized some aspects of the story, still tells a very odd tale indeed. People expecting a cross between Harry Potter and Jane Austen (another frequent reference made in entertainment coverage) will be caught off-guard.

I ordered the British Blu-ray, which came out on June 29 in the UK. It has excellent visual quality and a few mildly interesting extras, the most helpful dealing with the special effects. The American Blu-ray/DVD has a dreadful cover, nothing like the amusing portrait of the two title characters that graces the British version.

All page numbers are from the American first edition, Bloomsbury, 2004.

Chapter Four of my The Frodo Franchise deals with the way that studios control what reporters write through giving cast and crew certain talking points that get repeated over and over in the hundreds of promotional interviews that they will undergo at press junkets, on talk shows, and during public appearances.

One might ask why Norrell, having so little dramatic flair in his magic, puts on such an impressive show in York Minster. I wondered for a while whether this was an inconsistency in Clarke’s book but concluded that Norrell simply doesn’t see the difference. Magic is magic, and it should always impress people.

I am atypical in finding the last episode disappointing. Most reviews of it were positive. See again Anibundel for an intelligent and more enthusiastic view of it. The TV series was extensively covered on this site, and other entries are worth reading as well.

[August 20: Den of Geek has an interesting piece taking to task reviewers who compared the series to Harry Potter and generally gave the idea that it is for children. (Hardly. The British Blu-ray has a 15 rating.) I doubt that was the reason for the fall-off in viewership as the series continued, but it might have caused some people not to watch the show altogether.]

Filling the box: The Never-Ending Pan & Scan Story

The Limey (1999).

DB here:

Here’s a story, so far not finished.

Chapter 1: You can’t put ten pounds of mud in a five-pound sack (Dolly Parton)

Once upon a time, before home video and cable, movies were broadcast on television. They might be drawn from local TV stations’ 16mm collections or transmitted from the networks on “movie of the week” shows. When the film was a widescreen film, especially in anamorphic processes, it was adjusted, as we now say, “to fit your screen.”

That TV screen was in an aspect ratio of about 1.33:1 (4 x 3), like pre-1950s commercial films. But the film to be shown might be 1.75, 1.85, or 2.35. How to show it?

You could retain the whole original frame with letterboxing at top and bottom. This was done more often in Europe than in the US, I believe. Our TV system had 100 fewer lines, so the tiny picture area became quite degraded. And then (as now) there were people who persisted in believing that those black bars at top and bottom were somehow taking away part of the movie.

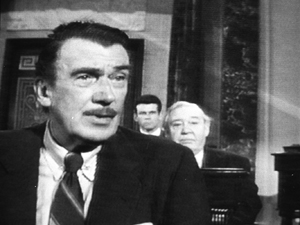

Far more common was the tactic of somehow making the wider image fill the box. This tactic came to be called “pan and scan.” It gained the name because in preparing the TV version, an engineer would sometimes swivel the TV frame across the original image, carving into it and sliding to and fro. The term pan and scan covered another tactic, simply making two shots out of one. We might call it “cut and scan.” Here’s an instance from an old VHS tape of Advise and Consent, one of the most daring American widescreen films. The slightly fatter faces are due to the distortion of the CRT monitor I shot from.

Sometimes there was neither scanning nor cutting, just simple cropping. The engineer would find a 4×3 chunk and extract it from the bigger image. To keep things simple, that chunk was usually around the center. This “center-cutting,” as it was called, could yield some funny results, as in the protruding nose in a 16mm TV print of Tarnished Angels.

Chapter 2: Shoot, protect, screw up

Some widescreen processes from the 1950s onward didn’t frame the image wide during filming. The image would be captured “full frame.” The result might later be “hard matted,” or letterboxed, during printing, as in the shot from The Limey surmounting today’s entry.

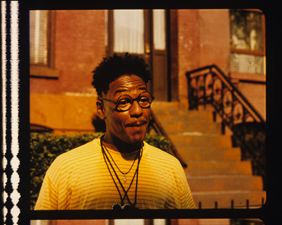

Sometimes, the 35mm theatrical prints would retain a 4:3 image, or something even squarer. The frames in a 35mm print of Do the Right Thing are about 1.19:1. Note the extensive headroom in the left image, from a 35mm print. For screenings the projectionist would mask the image to the proper proportions—typically 1.85. Here’s the version on the Criterion DVD, at 1.75 for widescreen monitors.

The full-frame image was available for cropping to 4:3 TV viewing. Many cinematographers used the “shoot and protect method” by composing for both 1.85 and 1.33.

There were problems with this “open matte” process in theatres. I recall a mis-framed version of Jerry Maguire in which the locker-room scene showed more of Cuba Gooding’s goodies than was intended. And a full-frame print of Godfather II reveals the duct-taped marks on the set floor (as if Pacino would ever hit them).

The same problem would appear in full-frame TV versions that were carelessly transferred from film. Microphones, unfinished stretches of the set, and other production elements might jut in. Some cinematographers didn’t consider TV versions important enough to worry about. “Fuck TV,” was heard occasionally.

More basically, the full-frame result wasn’t faithful to the “original” theatrical version, which was designed to be shown wide. Purists objected that TV versions, even if shot full-frame, didn’t fulfill the intention of the director.

Chapter 3: 16 into 9 won’t go

In the 1990s there came laserdiscs and DVDs. These offered properly letterboxed framings. Cinephiles cheered. It seemed that the days of pan and scan were over.

In the 1990s there came laserdiscs and DVDs. These offered properly letterboxed framings. Cinephiles cheered. It seemed that the days of pan and scan were over.

Actually, pan-and-scan hung on quite a bit. Many laserdisc editions weren’t letterboxed. Airline versions offered cropped images, and still do. (Those tiny screens, after all.) Some DVDs were released in pan-and-scan versions, while others offered a letterboxed version of the film on one side of the disc and a full-frame version on the other. But serious cinephiles could assume that the general public was starting to understand that films intended to be seen at a certain ratio should be shown that way.

As the new disc formats emerged, so did a plan to standardize High Definition video for a 16 x 9 display. The European Union promoted it during the mid-1990s, and over the next twenty years it became accepted for both computer monitors and video displays. The new format developed in sync with the gradual replacement of analog broadcasting by HD transmission.

The problem is that 16:9 is a ratio of 1.77:1, close enough to 1.85 for most purposes but far off the ratio of 2.20:1 (many 70mm films) and 2.40 (anamorphic widescreen after about 1970). Yet maybe this isn’t a problem. Why not just letterbox those wider images within the 16:9 format?

If only things were so simple.

Chapter 4: Slightly off, and more

Today, at least 77% of US households have HD monitors. (Surprisingly, 41% of TVs still in use are Standard Definition, many presumably comforting children and old people.) Broadcasters make concessions to the 4:3 ratio by keeping the key action centered and cropping the 16:9 image.

Nature abhors a vacuum, and TV monitors apparently can’t bear blank space. So some purveyors of movies on video have updated pan-and-scan for the HD age. Cable, for instance.

It’s been years since I clicked my cable remote to the Sundance Channel and the Independent Film Channel, now known as IFC. Seeing them a couple of weeks ago was a mild shock. Now each boasted a bug in the lower right corner, and swarming over the image were lots of texts plugging other programs. Worse, there were commercials for weight-loss scams, Burger King, and Portlandia. More to the point here, these services give us a new version of pan-and-scan.

Thanks to the center-cutting method, I found plenty of examples of anamorphic 2.40 films sliced up to fit our monitor. Here are a couple of examples from IFC’s version of Jaws. In the first pair, the wider image gives Bruce room to move, and Brody is more salient. In the second pair, Hooper is speaking, but in the IFC image he’s even more peripheral than Mr. Nose in Tarnished Angels.

In rare cases, IFC seems to run full-scope prints; I spotted one of Chinatown. But it doesn’t seem to be the norm. Maybe IFC’s New Age pan-and-scan is trying to live up to the channel’s slogan: “Always on. Slightly off.”

Many films of the early widescreen era are compromised even at 16:9. The nose shot from Tarnished Angels would be a bit cramped in a 1.77 format, and many other shots would suffer as well.

When the wide format was still new, filmmakers were exploring what they could do it, and that included scattering important information throughout the frame. Preminger was all over the place in the Senate and Committee-Room scenes of Advise and Consent. What would you do to fit these shots into 16:9? I make a silly stab at center-cutting.

Films like this remind you of how the technology of home video has made our filmmakers less daring in their compositions. Would anyone today risk the bold composition that Richard Fleischer uses in the mortuary scene of Compulsion? As you can see from the image at the end of the entry, the crucial pair of eyeglasses rests on the lower frameline, as if on a shelf. ‘Scope nudged some directors toward quite intricate shot designs.

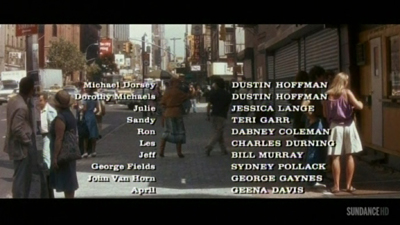

By the time Tootsie was made, with home video on the rise, filmmakers were pressed to shoot and protect better. So here there’s plenty of unused space on the sides, and most action will fit into any old frame proportions. In the shot below, the 1.33 version (available on the flip side of the DVD) is extracted from the Scope version (and slightly squeezed as well). The 1.77 version I grabbed from the Sundance Channel is also extracted from the wider framing. Both reframe the image to emphasize Michael and Jeff, the comic duo. The original 2.35 image centers the food counter and for some reason gives equal space to the inconsequential aisle and stove on the right.

Obviously, composition isn’t particularly important here. Solid as Tootsie is at the level of writing and performance (“Oh, God, I begged you to get some therapy”), we wouldn’t point to it as a model of pictorial finesse.

Moreover, pan-and-scan isn’t just a matter of retaining the action in different framings. Recasting the image changes the scale of the things in it. Old TV pan-and-scan, as in my first Advise and Consent example, makes the figures chopped out of the composition seem closer to us. Sometimes today’s pan-and-scan makes the figures seem smaller. That’s because the full-frame original image offers a bit more space at the top or bottom than we see in the anamorphic version, and that gets incorporated into the 1.77 or 1.33 version. (You can see it in the Jaws example above, with the space above Quint’s head.)

The push-pull of different versions is particularly noticeable in close views. The center-cut (and perhaps slightly squeezed) IFC version of The Matrix keeps Cypher prominent in the foreground, with the car crash in the rear. Yet do you see him and the crash as closer to us in the wide original? I do. Maybe it’s because both Cypher and the background plane are larger in the second frame.

By contrast, several shots in the IFC version of The Matrix have areas at the top and bottom not visible in a wider-frame DVD. In any case, extracting from an anamorphic frame or here, pulling the 1.77 version out of a full frame, can subtly alter the scale and perspective relations within the shot.

In the old TV days, networks would show credit sequences in full widescreen, as they were obliged to make all the contributors’ names visible. So you often had the odd situation of a widescreen credits sequence that would end a movie shown in 4:3. Sundance has updated the technique. Tootsie’s penultimate shot of Julie is at 1.77, but as she and Michael walk off, we cut immediately to a final shot at 2.35 letterboxed, over which the credits roll.

Another old trick has been revived. Back in 1960s TV, you’d have an obligatory widescreen image with credits information, but the shot might go on to show story action. Then the TV framing would close in on the wide image and gradually fill the screen with a 4:3 composition. Damned if I didn’t find the same thing happening last weekend on Sundance. The opening credits for The Graduate were in full ‘scope. That shot dissolved to the famous shot of Benjamin sitting in front of his aquarium, blankly facing the camera.

To retain the credits and keep the dissolve smooth, the engineer slowly enlarged the original shot to 16:9 proportions as Ben’s father comes in. (You can see the Sundance bug lift slowly into the lower right of the image.)

The result is a camera movement, a zoom in, that isn’t in the original film. In the original framing below, the shot scale on Ben isn’t much different, but the little scuba diver remains prominent in a way he isn’t in the 16×9 image.

Chapter 5: VOD = Variants On Demand

On cable TV we Americans can go to TCM for a purer experience of widescreen from the old days. But the more recent films shown on IFC, Sundance, Pivot, and other cable channels are likely to be hacked up in the new way. In this respect as well as others, cable has become the network TV of the new age. We get shows of all types, not just sports and movies but original series, except that now we get to pay to watch commercials.

Surely things are better with streaming?

In the spot-checking I did on Amazon and Hulu Plus, I didn’t find instances of cropping. In particular, the Criterion films I checked retain their proper aspect ratios. Netflix is another story. At this point we must thank the anonymous genius behind What Netflix Does. This site exposes a great many ways that the most popular streaming service has relied on pan-and-scan, with different crops for different markets.

In fairness, once the anonymous genius contacted Netflix, some deficient versions were replaced by proper ones. But several of the more recent examples have not been changed. Who knows how many others remain panned and scanned because the alterations haven’t yet been detected?

In the light of all this, I’m wondering if filmmakers have been protesting this mangling of their work. During the early days of TV broadcasts, directors complained about cuts and commercials, and in more recent years we’ve learned that directors were won over to digital projection in theatres because then “the film would be shown exactly as the director intended.” With many more people seeing the film on video platforms than see it in theatres, you’d think we’d have heard more from the creative community. Once more their movies are being jammed and lopped to fit whatever box they’re put in.

I’m tempted to say that when we want to get the movie in a form close to the ways its makers wanted it to be seen, we need to see it in a theatre or get it on DVD/Blu-ray. There are exceptions, of course. Theatres can botch aspect ratios today just as they have in earlier decades, chiefly by using the wrong masking. And we have filmmakers who alter the aspect ratio on DVD, usually to expand the field from 2.35:1 to 1..77 in hopes (vain) of evoking the Imax effect (Tron: Legacy, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire).

Without getting into technicalities, some of the 1.77 versions you’ll see have a bit more area at the top and the bottom of the frame than we find in the full anamorphic image. In many cases, like the shot of Cypher in The Matrix, it’s because the film was shot in Super-35. This very full-frame capture format allowed filmmakers to extract a 2.40-proportioned image, or a 4:3 image, or images in other aspect ratios. The Wikipedia entry on Super-35 is very helpful on this and other aspect ratios, both for cinema screens and TV. Some shots in the IFC Jaws had a little more vertical area as well. I assume that’s because the ‘scope image on the DVD cropped a tad off the top and bottom of the full-frame image on the film.

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for pointing me toward the site What Netflix Does. More general thanks to James Quandt for our long-running conversation about aspect ratios. Other entries on aspect ratio on this site involve Fritz Lang, Jean-Luc Godard, and Wes Anderson. I set out some ideas on CinemaScope aesthetics in this video lecture.

P.S. 28 January: Thomas Zorthian was ahead of the curve on this. Back in 2011 he noticed the Netflix pan-and-scan.

Your article hit home for me as I have been trying to bring attention to this problem for a while. I even wrote Roger Ebert hoping he could use his influence. He was kind enough to publish my letter: http://www.rogerebert.com/letters/netflix-stream-sometimes-overflows-the-banks. I have also written to HBO and am considering a petition to ask them to show movies in the proper ratio before HBO GO becomes a standalone service. This would enhance the value of this new service.

Thanks to Thomas for corresponding!

Compulsion (1959).

Auteurist on the sound stage

River’s Edge (1987).

DB here:

Last November, Joe Dante brought his brand of manic legerdemain to Madison. This year, his pal and contemporary Tim Hunter visited. Tim talked with us about directing, watched an abundance of movies (from 1930s Wellman classics to Hong Kong gunfests), and oversaw a screening of his 1987 classic River’s Edge. A genial presence and 110% cinephile, Tim was continually stimulating. A blog was a necessity.

Grinding it out

Hunter has made several theatrical features, most famously River’s Edge and The Saint of Fort Washington (1993), but for many years he has also been a free-lance director for top television series, mostly on premium cable. Unlike Dante, whose forte is grotesque comedy and satire, Hunter brings a strong sense of dramatic realism to both movies and television. Over twenty years and more than sixty episodes, he has directed major installments of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Dexter, Deadwood, Law & Order, Cold Case, and Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Apart from efficient craft, he brings to these projects a baby-boomer cinephilia. “I’m an old-school movie brat.” Born in 1947 (about a month before me), he grew up watching classic films. His father was a screenwriter, and in his application interview for Harvard, he won entrance, he thinks, with a rapid-fire analysis of Psycho. As an undergraduate, he ran film societies and made student films. He attended the AFI directors program in 1970 and began teaching film studies at UC-Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, he was writing screenplays. Over the Edge (1979), written with Charlie Haas, was sold to Orion and directed by Jonathan Kaplan. Soon Hunter was able to get backing for Tex (1982), his first directed feature.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a result, the key question—where to put the camera?—has to be settled swiftly. “You need an efficient plan.” Hunter likes to walk the set a day or two before production begins, in order to figure out his setups and actor blocking. The big decision is whether to used a fixed camera or a “moving master,” a tracking shot that reveals the players and the setting, but one that can be interrupted by closer views. He argues that performers prefer sustained shots. “The longer you can play it, the better for the actors.”

To sustain the shots, most dialogue scenes are covered by at least two cameras. That way the scene can be played out in something like real time, with each camera yielding a continuous take centered on one actor or another. The two camera takes can then be cut together into shot/ reverse-shot patterns.

You can see the efficiency of this. The “Perception” episode of Revenge (2012) contains about 780 shots in 42 minutes; of these, at least 350 are shots that repeat setups. A similar proportion can be seen in Hunter’s first episode of Twin Peaks from 1990; about half of the shots repeat earlier camera setups. Because of the time pressure, the director must stage the scenes with adequate coverage from two or more angles.

This can lead to a routine, zero-degree style: Little complex staging, more reliance on actors sitting or standing. Shoot master shot, reverse angles, and singles for reaction shots. Why not use long-held two-shots or fuller framings, as we find in classical Hollywood studio films? Breaking up the camera takes permits the editor to control when we see facial reactions, to tighten the rhythm, and to eliminate fluffed lines. Quick intercutting also supplies that pepped-up pace that, TV practitioners believe, keep viewers glued to the screen.

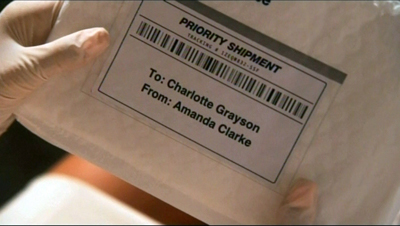

Hunter looks for ways to inject something different, often based on his tastes in classical cinema. For instance, he admires the melodramas of Minnelli and Sirk, so you aren’t surprised to see sudden high or low angles in moments of confrontation. In the “Perception” episode of Revenge, the script gave him a chance for “a Marnie moment.” The heroine Emily has prepared a video that reveals the wealthy Charlotte Grayson’s real parentage. She’s gratified when she sees the maid set the envelope at the foot of the staircase for Charlotte to notice.

Later, overhearing an emotional scene between Charlotte and her father, Emily repents her scheme and tries to retrieve the envelope before Charlotte can find it. Hunter points out that the scene gained suspense when he broke it up into “inserts and moving point-of-view shots.”

The result is a somewhat Hitchcockian byplay, as Emily, startled by the vengeful matriarch Victoria, drops the envelope and tries to keep her from identifying it.

Neatly, Victoria’s face slips into the low-angle view at the very end of the shot, preparing us for her sudden entrance when Emily turns around. And the envelope falling addressee-side down sustains the suspense.

Consciously arty

However much you inject your own emphases, Hunter explained, the director has to assess the visual style of each show and maintain it, so you “tailor your style to the show.” Homicide was 100% handheld, and for that you need a cinematographer who is master of that look. By contrast, Mad Men is more “pictorially precise” and harks back to the studio movies of the 1950s. (Jim Emerson has painstakingly analyzed the felicities of the Mad Men look in several blog entries and video essays.)

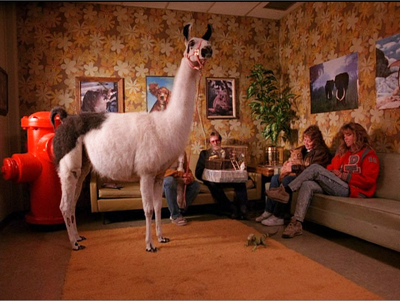

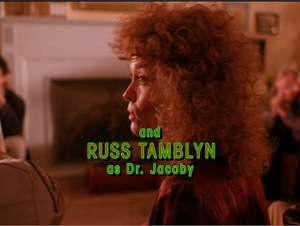

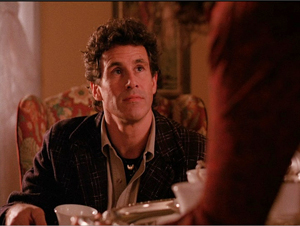

Another pictorially precise show was Twin Peaks, and Hunter’s contribution to the first season (episode four) was one of the most memorable. In that episode we meet Killer Bob’s intimate friend who’s introduced in a shot at once chilling and funny. “Keep your hands where I can see ’em,” snaps Sheriff Harry Truman, and we get this.

At other moments, in an echo of 1940s deep-focus, Hunter uses split-focus diopters to keep foreground and background plane crisp.

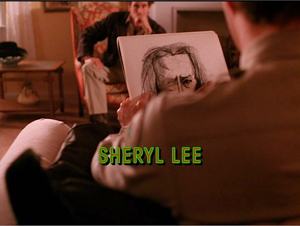

The opening displays the sort of calm assurance that Hunter could bring to a show that was, as he put it, “consciously arty.” A moving master takes us from a photo of the dead Laura to Deputy Andy sketching Killer Bob to Sarah Palmer giving her description; it ends on a framing of Donna, taking it all in uneasily. Donna won’t move or say anything in the scene, but this shot’s ending prepares for both the final shot and her expanding role in the episode’s plot.

In the course of the scene, Hunter supplies closer views anchored by a fixed master setup of the parlor.

When Leland Palmer comes in to say that his wife has had another vision, and when Sarah rises to describe it, we get a long-lens framing, presumably from the B camera aligned with the camera that supplied the master framing.