Archive for the 'The Ten Best Films of…' Category

The ten best films of … 1920

High and Dizzy

Kristin here:

Three years ago, we saluted the ninetieth anniversary of what was arguably the year when the classical Hollywood cinema emerged in its full form. The stylistic guidelines that had been slowly formulated over the past decade or so gelled in 1917. We included a list of what we thought were the ten best surviving films of that year.

In 2008 we again posted another ten-best list, again for ninety years ago. This annual feature has become our alternative to the ubiquitous 10-best-films-of-2010 lists that print and online journalist love to publish at year’s end. It’s fun, and readers and teachers seem to find our lists a helpful guide for choosing unfamiliar films for personal viewing or for teaching cinema history. (The 1919 entry is here.)

There were many wonderful films released in 1920, but, as with 1918, I’ve had a little trouble coming up with the ten most outstanding ones. Some choices are obvious. I’ve known all along that Maurice Tourneur’s The Last of the Mohicans (finished by Clarence Brown when Tourneur was injured) would figure prominently here. There are old warhorses like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Way Down East that couldn’t be left off—not that I would want to.

But after coming up with seven titles (eight, really, since I’ve snuck in two William C. de Mille films), I was left with a bunch of others that didn’t quite seem up to the same level. Sure, John Ford’s Just Pals is a charming film, but a world-class masterpiece? A few directors made some of their lesser films in 1920, as with Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow or Lubitsch’s Sumurun. Seeing Frank Borzage’s legendary Humoresque for the first time, I was disappointed—especially when comparing it with the marvelous Lazy Bones of 1924. (Assuming we continue these annual lists, expect Borzage to show up a lot.) Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1920, and Keaton and Lloyd were still making shorts, albeit inspired shorts. Mary Pickford’s only film of the year, the clever and touching Suds, is a worthy also-ran. Choosing Barrabas over The Parson’s Widow or Why Change Your Wife? over Sumurun has a certain flip-of-the-coin arbitrariness, but we wanted to keep the list manageable. But they all repay watching.

The year 1920 can be thought of as a sort of calm before the storm. In Hollywood a new generation was about to come to prominence. Griffith would decline (Way Down East may be his last film to figure on our lists). Borzage will soon reach his prime, as will Ford. Howard Hawks will launch his career, and King Vidor will become a major director. The great three comics, Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd will move into features. In other countries, an enormous flowering of new talent will appear or gain a higher profile: Murnau, Lang, Pabst, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dozhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Jean Epstein, Pabst, Hitchcock, and others. The experimental cinema will be invented, and Lotte Reiniger will devise her own distinctive form of animation. Watch for them all in future lists, which will be increasingly difficult to concoct

In the meantime, here’s this year’s ten (with two smuggled in). Unfortunately, some of these films are not available on DVD. They should be.

The great French emigré director Maurice Tourneur figured here last year for his 1919 film Victory. The Last of the Mohicans is just as good, if not better. I haven’t read the Cooper novel, set during the French and Indian War, but it’s obvious that Tourneur has pared down and changed the plot considerably. The sister, Alice, is made a less important character, with the plot focusing on two threads: the Indian attack on the British population as they leave their surrendered fort and on the virtually unspoken attraction between the heroine Cora and the Mohican Indian Uncas. The seemingly impassive gazes between these characters, forced to conceal their attraction, convey more passion than many more effusive performances of the silent period. The actress playing Cora also wore less makeup than was conventional, de-glamorizing her and making her a more convincing frontier heroine.

The film is remarkable for its gorgeous photography, with spectacular location landscapes, some apparently shot in Yosemite (below left). Tourneur’s signature compositional technique of shooting through a foreground doorway or cave opening or other aperture appears frequently (below right). (Brown’s account of the filming in Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By makes it sound as though he shot most of the picture, but in watching the film I find this hard to believe.)

Finally, the film stands out from most Hollywood films of its day for its uncompromising depiction of the ruthless violence of the conflict between the British and those Indians allied with the French. The scene in which the inhabitants of the fort leave under an assumed truce and are massacred can still create considerable suspense today, and the outcome puts paid to the notion that all Hollywood films end happily.

The word melodrama gets tossed around a lot, and many would think of much of D. W. Griffith’s output as consisting of little besides melodramas. But Way Down East is the quintessential film melodrama. An innocent young woman (Lillian Gish) is lured into a mock marriage and ends up deserted and with a baby. The baby dies and she finds a place as a servant to a large country family, where the son (Richard Barthelmess) falls in love with her. Her sinful status as an unwed mother leads the family patriarch to order her out, literally into the stormy night. She ends up on an ice flow, headed toward a waterfall. Along the way there’s comic relief from some country bumpkins and a naive professor who falls for the hero’s sister. It all works, partly because Griffith treats the main plot with dead seriousness and partly because Gish elicits considerable sympathy for her character.

Not only is it a great film, but it provides a window into the past, preserving a popular nineteenth-century play and giving insight into the drama of that era. It’s hard to think of another feature film that conveys such a genuine record of the Victorian theater, directed by a man who had made his start on the stage of the same period. (Unfortunately the film does not survive complete. The Kino version linked above is from the Museum of Modern Art’s restoration, which provides intertitles to explain what happens during missing scenes.)

Way Down East displayed a conservative attitude toward sex that was rapidly receding into the past–at least as far as the movies were concerned. The same year saw two films that set the tone for the Roaring ’20s in their more risqué depiction of romantic relationships: Cecil B. De Mille’s Why Change Your Wife? and Mauritz Stiller’s frankly titled Swedish comedy Erotikon.

De Mille has featured on our previous lists, for Old Wives for New in 1918 and Male and Female in 1919. Why Change Your Wife? ramped up the sexual aspect of the plot, however, as a Photoplay reviewer made clear: “”Having achieved a reputation as the great modern concocter of the sex stew by adding a piquant dash here and there to Don’t Change Your Husband, and a little more to Male and Female, he spills the spice box into Why Change Your Wife?” The plot is not nearly as daring as this suggests. Gloria Swanson plays a wife who is straight-laced and intellectual, driving her husband to spend time with a stylish woman who tries to seduce him. Yet he flees after one kiss, and after his wife divorces him on the assumption that he has cheated on her, he marries the seductress. The heroine discovers the error of her ways and becomes sexy in her dress and behavior. As a result the husband regains his old love for her, and they remarry. No actual adultery occurs, and the first marriage is affirmed with a happy ending.

Why Change Your Wife? may have seemed more daring because De Mille here externalizes the shifting relationships through the costumes to the point where no viewer could miss the implications. Initially the wife’s demure dresses mark her as prudish, while the woman who lures her husband away is dressed like a vamp. Once the wife lets go, she dons similar revealing, expensive designer clothes. As a result, the male members of the audience might revel in a fantasy of their ideal wife, and the women would delight in displays of fashions most of them could never own in reality. It proved a successful combination. We tend to forget it now, but the 1920s was full of variants and imitations of Why Change Your Wife?, often featuring a fashion-show scene that was nothing but a parade of models in outlandish clothes. (Early Technicolor was sometimes shone off in such sequences.) Top designers like Erté were recruited to bring their talents to such films.

Fashion as a selling point in films remains with us. The glossy new version of The Hollywood Reporter, recently decried by David, now has a regular “Hollywood Style” section. The November 24 issue ran “Costumes of The King’s Speech,” and the December 1 issue describes “Fashions of The Tourist,” with photos of Angelina Jolie in her various costumes. In addition to shots of the stars, both articles feature enticing close-ups of lipstick, shoes, jewelry,and purses.

A double feature of Why Change Your Wife? and Erotikon would provide a vivid sense of the differing moral outlooks of mainstream America and Europe in the post-war years. In Erotikon, the situation is reversed. An absent-minded entomologist neglects  his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

Erotikon reflects some of the influences from Hollywood that were seeping into European films after the war. Sets are larger, cuts more frequent (though not always respecting the axis of action), and three-point lighting crops up occasionally. Yet Stiller maintains the strengths of the Scandinavian cinema of the 1910s, with skillful depth staging (left) and a dramatic use of a mirror. In the opening of a crucial scene where the sculptor confronts the wife with her adultery, tension builds because she does not know he is watching her until she sees him in the mirror (see bottom). Still, apart from its European sophistication, Erotikon could pass for an American film of the same era. Stiller and lead actor Lars Hansen would both be working in Hollywood by the mid-1920s.

I can’t allow the nearly unknown director William C. de Mille to take up two slots this year, though it’s tempting. William’s career was shorter than that of his much better-known brother Cecil. It peaked in 1920 and 1921, though, and I still look back fondly on the films by him that were shown in “La Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival of 1991. That year saw a large retrospective of Cecil’s films, and the organizers wisely decided to include a  sampling of William’s surviving work.

sampling of William’s surviving work.

The two men’s approaches were markedly different. Where Cecil by this point was setting his films among the rich and using visual means like costumes to make the action crystal-clear to the audience, William was more likely to favor middle-class settings with small dramas laced with humor and presented with restrained acting and small props. Despite William’s skill as a director and his ability to create sympathy for his characters, he never gained much prominence, especially compared to his brother. He retired from filmmaking in 1932, at the relatively young age of 54. Yet obviously he was attuned to his brother’s style, having written the script for Why Change Your Wife? It may be characteristic of the two that Cecil capitalized the De in De Mille, while William didn’t.

Relatively few of William’s films survive, but these include two excellent films from 1920, Jack Straw and Conrad in Quest of His Youth. I don’t remember Jack Straw well enough to describe it. It involved the hero’s falling in love with a woman when they both live in the same Harlem apartment building. When her family becomes rich, Straw disguises himself as the Archduke of Pomerania in order to woo her. Sort of a Ruritanian romance but played out in the U.S.

I remember Conrad in Quest of His Youth better. The hero returns from serving as a soldier in India. He feels old and decides to try and recover his youth. The first attempt comes when he and three cousins agree to return to their childhood home and indulge themselves in the simple pleasures of their youth. Eating porridge for breakfast is a treasured memory, but the group discovers that this and other delights are no longer enjoyable to them as adults. Conrad goes on to seek romance elsewhere and eventually finds a woman who makes him feel young again. The film’s poignant early section manages in a way that I’ve never see in any other film to convey both nostalgia for the joys of childhood and the sad impossibility of recapturing them.

Neither film is available on DVD. Indeed, I couldn’t find an image from either to use as an illustration. The only picture I located is a rather uninformative one from Conrad in Quest of His Youth, above right, which I scanned from William C.’s autobiography (Hollywood Saga, 1939). It’s no doubt an indicator of William’s modesty that the frontispiece of this book is a picture of his brother directing a film.

Maybe this entry will serve as a hint to one of the DVD companies specializing in silent movies that these two titles deserve to be made available. They’re high on my list of films I would love to see again.

Most people who study film history see Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari very early on, though they probably push it to the backs of their minds later on. I have a special fondness for Caligari precisely because I did see it early on. I took my first film course, a survey history of cinema, during my junior year. Maybe I would have gotten hooked and gone on to graduate school in cinema studies anyway, but it was Caligari that initially fascinated me. It was simply so different from any other films I had seen in what I suddenly realized was my limited movie-going experience. It inspired me to go to the library to look up more about it, a tiny exercise in film research.

Some may condemn it as stage-bound or static. Despite its painted canvas sets and heavy makeup, however, it’s not really like a stage play. Many of the sets are conceived of as representing deep space, though often only with a false perspective achieved by those painted sets:

Still, in an era when experimental cinema was largely unknown, Caligari was a bold attempt to bring a modernist movement from the other arts, Expressionism, into the cinema. It succeeded, too, and inaugurated a stylistic movement that we still study today.

I haven’t watched Caligari in years (I think I know it by heart), but I’m still fond of it. The plot is clever grand guignol. It has three of the great actors of the Expressionist cinema, Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, and Lil Dagover, demonstrating just what this new performance style should look like. The frame story retains the ability to start arguments. The set designs area dramatically original, and muted versions of them have shown up in the occasional film ever since 1920. Even if you don’t like it, Caligari can lay claim to being the most stylistically innovative film of its year.

As I did for our 1918 ten-best, I’m cheating a bit by filling one slot of the ten with a pair of shorts by two of the great comics of the silent period. Both have matured considerably in the intervening two years. In 1918, Harold Lloyd was still working out his “glasses” character. By this point he is much closer to working with his more familiar persona. Similarly, in 1918, Buster Keaton was still playing a somewhat subordinate role in partnership with Fatty Arbuckle. In 1920, he made his first five solo shorts, co-directing them with Eddy Cline.

The Lloyd film I’ve chosen is High and Dizzy, the second short in which he went for “thrill comedy” by staging part of the action high up on the side of a building. (See the image at the top.) Four years later he would build a feature-length plot around a climb up such a building in Safety Last, one of his most popular films. In High and Dizzy, Harold is not quite the brash (or shy) young man he would soon settle on as the two variants his basic persona. The opening shows him as a young doctor in need of patients. He soon falls in love with the heroine, and through a drunken adventure, ends up in the same building where she lies asleep. She sleepwalks along a ledge outside her window, and when Harold goes out to rescue her, she returns to her bedroom and unwittingly locks him out on the ledge. The film is included in the essential “Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection” box-set, or on one of the two discs in Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” Vol. 2.”

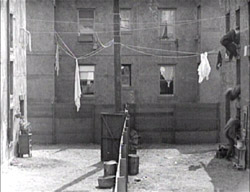

Neighbors was the fifth of the five Keaton/Cline shorts made in 1920. (It was actually released in early 1921, but I’ll cheat a little more here; there are other Keaton films to come in next year’s list.) It’s a Romeo and Juliet story of Keaton as a boy in one working-class apartment house who loves a girl in a mirror-image house opposite it. Two bare, flat yards with a board fence running exactly halfway between them separate the lovers. Naturally the two sets of parents are enemies.

Lots of good comedy goes on inside the apartment blocks, but the symmetrical backyards and the fence inspire Keaton. We soon realize that his instinctive ability to spread his action up the screen as well as across it was already at play. The action is often observed straight-on from a camera position directly above the fence, so that we–but usually not the characters–can see what’s happening on both sides. For one extended scene involving policemen, Keaton perches unseen high above them, hidden. Even though we can’t see him, the directors keep the framing far enough back that the place where we know he’s lurking is at the top of the frame as we watch the action unfold. The playful treatment of the yard culminates in an astonishingly acrobatic gag that brings in Keaton’s early music-hall talents.

The boy and girl have just tried to get married, but her irate father has dragged her home and imprisoned her in a third-floor room. She signals to Keaton, across from her in an identical third-floor window. A scene follows in which two men appear from first- and second-story windows below Keaton, and he climbs onto the shoulders of the two men below. This human tower crosses the yard several times, attempting to rescue the girl; each time they reach the other side, they hide by diving through their respective windows:

They perform similar acrobatics on the return trips to the left side, carrying the bride’s suitcase or fleeing after her father suddenly appears.

Neighbors is included as one of two shorts accompanying Seven Chances in the Kino series of Keaton DVDs, available as a group in a box-set.

Our final two films lie more in David’s areas of expertise than mine, so at this point I turn this entry over to him.

DB here:

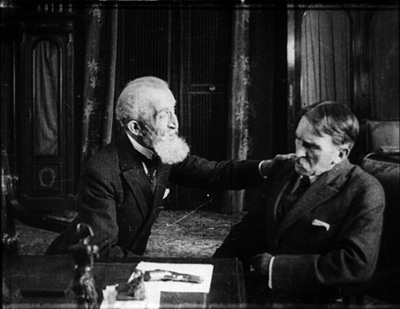

With Barrabas Feuillade says farewell to the crime serial. Now the mysterious gang is more respectable, hiding its chicanery behind a commercial bank. Sounds familiar today. As Brecht asked: What is robbing a bank compared with founding a bank?

Over it all towers another mastermind, the purported banker Rudolph Strelitz. In his preparatory notes Feuillade called him “a sort of sadistic madman, a virtuoso of crime . . . a dilettante of evil.” Against Strelitz and his Barrabas network are aligned the lawyer Jacques Varèse, the journalist Raoul de Nérac (played by reliable Édouard Mathé), and the inevitable comic sidekick, once again Biscot (so perky in Tih Minh).

The film’s seven-plus hours (or more, depending on the projection rate) run through the usual abductions, murders, impersonations, coded messages, and chases. But there’s little sense of the adventurous larking one finds in Tih Minh (1919), in which the hapless villains keep losing to our heroes. The tone of Barrabas is set early on, when Strelitz forces an ex-convict into murder, using the letters of the man’s dead son as bait. The man is guillotined. The epilogue rounds things off with a series of happily-ever-afters in the manner of Tih Minh, but these don’t dispel, at least for me, the grim schemes that Strelitz looses on a society devastated by the war. Add a whiff of anti-Semitism (the Prologue is called “The Wandering Jew’s Mistress”), and the film can hardly seem vivacious.

According to Jacques Champreux, Barrabas was the first installment film for which Feuillade prepared something like a complete scenario, although it evidently seldom described shots in detail. The film has a quick editing pace (the Prologue averages about three seconds per shot), but that is largely due to the numerous dialogue titles that interrupt continuous takes. With nearly twenty characters playing significant roles and some flashbacks to provide backstory, there’s a lot of information to communicate.

Of stylistic interest is Feuillade’s movement away from the commanding use of depth we find in Fantômas and other of his previous masterworks. Here the staging is mostly lateral, stretching actors across the frame. Very often characters are simply captured in two-shot and the titles do the work, as if Feuillade were making talking pictures without sound. Once in a while we do get concise shifting and rebalancing of figures, usually around doorways. Here Jacques vows to go to Cannes and tell the police of the kidnapping of his sister. As Raoul and Biscot start to leave, Jacques pivots and says goodbye to Noëlle, creating a simple but touching moment of stasis to cap the scene.

Full of incident but rather joyless, Barrabas will never achieve the popularity among cinephiles of the more delirious installment-films, but it remains a remarkable achievement. The ciné-romans that would follow until Feuillade’s death in 1925 would lack its whiff of brimstone. They would mostly be melodramatic Dickensian tales of lost children, secret parents, strayed messages, and faithful lovers. Barrabas is not available on DVD.

You might think that a movie that opens with a frowning old man studying a skeleton would also be somewhat unhappy fare. Such isn’t actually the case with Victor Sjöström’s generous-hearted Mästerman, a story of a village pawnbroker obliged to take a young woman as a housekeeper. With his stovepipe hat and air of sour disdain, Samuel Eneman, known to the village as Mästerman, is a ripe candidate for rehabilitation. Once Tora is installed and has put a birdcage (that silent-cinema icon of trapped womanhood) on the window sill, the scene is set for Mästerman’s return to fellow feeling. But she is there merely to cover the debts and crime of her sailor boyfriend, and eventually Eneman realizes he must make way for young love. The drama is played out in front of the townspeople, and as often happens in Nordic cinema (e.g., Day of Wrath, Breaking the Waves) the community plays a central role in judging, or misjudging, the vicissitudes of passion.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

For a valuable source on Feuillade’s preparation for Barrabas and other of his works see Jacques Champreux, “Les Films à episodes de Louis Feuillade,” in 1895 (October 2000), special issue on Feuillade, pp. 160-165. I discuss Feuillade’s adoption of editing elsewhere on this site.

Tom Gunning provides an in-depth discussion of Sjöström’s style at this period in “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930, ed. John Fullerton and Jan Olsson (Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), pp.204-231. For more on some of the directors discussed in this entry, check the category list on the right.

Erotikon.

The ten-plus best films of … 1919

KT here, with some help from DB:

Two entries are enough to create a tradition. Once again, at a time of year when critics are picking their 10-best lists for 2009, we jump back ninety years and give our choices for 1919.

(For our 1917 list, see here, and here for 1918.)

I remarked in last year’s post that it was a bit difficult to come up with ten films, a result perhaps of accidents of preservation or slackening of activity by certain major filmmakers. There was no such problem for 1919, and films had to be bumped off the initial list to keep it to ten. (In fact, you’ll notice we didn’t quite manage to keep it to ten.) Since some people may take these lists as a guide to exploring the cinema of the teens, we’re adding some also-rans at the end, all very much worth watching.

With 1919, we’re approaching the decade when many of the most widely known silent classics were made. Some titles on this year’s list will be very familiar. Erich von Stroheim’s first film came out in 1919, as did Carl Dreyer’s. Ernst Lubitsch, always a prolific director, was particularly busy that year. Other titles are less well-known, still being largely the province of silent-film festivals and archival research.

Three, sadly, are not available on DVD, and some others have to be ordered from sources in their countries of origin. In this day of internet sales around the world, such orders are not difficult. You need, however, a multi-region DVD player.

Charles Chaplin had long since left his knockabout comedy behind and was making more controlled, poetic films by  this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

Cecil B. De Mille had begun his series of high-society battle-of-the-sexes films by this point. Male and Female differs from the others in that it is based on a prominent literary source, The Admirable Crichton, J. M. Barrie’s successful 1902 play. The plot involved the butler of a wealthy British family. He becomes their leader when the pampered group is cast away on an unpopulated island. A romance develops between the spoiled daughter, Lady Mary (Gloria Swanson), and Crichton (Thomas Meighan).

De Mille spiced up the story with a fantasy scene based on William Ernest Henley’s popular poem of 1888, “I was a King in Babylon.” It dealt with reincarnation, one of several spiritualist fads of the period, which also included psychic contact with the dead and the fairy photographs that deluded Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Crichton refers to the poem, leading into a scene of him as king in a Babylon. When a Christian slave girl rejects his advances, he orders her thrown to the lions. The scene providesa glimpse of the costume-epic style that De Mille would increasingly turn to as his career advanced.

Henley, by the way, is largely forgotten today, but another of his poems, “Invictus,” inspired Nelson Mandela and lends its name to the latest Clint Eastwood film.

D. W. Griffith released an impressive lineup of features in 1919, despite the fact that he was also acting as the producer for other directors. His output includes a charming set of pastoral stories A Romance of Happy Valley, True Heart Susie, and The Greatest Question; a belated war film, The Girl Who Stayed at Home; a Western, Scarlet Days; and a melodrama that ranks among his most admired films, Broken Blossoms. Griffith’s status within the industry was  reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

Broken Blossoms owes its simplicity to the fact that Griffith was then making a series of films based on short stories. The title of Thomas Burke’s “The Chink and the Child” sounds offensive today, but it was an ironic reference to the epithet forced upon an idealistic young Chinese man who comes to London’s grim Limehouse district and becomes disillusioned. He falls in love with the delicate Lucy, abused by her violent, drunken father. These three form the main characters. Another Chinese man lusts after Lucy, but for once in Griffith’s work, the sexual threat to the innocent heroine takes second place to her abuse by her father. Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess convey the quiet resignation that at intervals gives way to Donald Crisp’s vicious outbursts.

Apart from the strong performances from the three leads, the film was perhaps the first to consistently use the “soft style” of cinematography, an approach that borrowed from a recently established trend in still photography. The hazy views of the Chinese setting in the opening and of the Limehouse docks later on would be enormously influential on films of the 1920s.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

The Sentimental Bloke was restored in 2004 and this past April appeared in a DVD set prepared by the Australian National Film & Sound Archive. A supplementary disc includes historical material, information on the new musical accompaniment, and an interview with Longford. A book of historical essays is also included in the box, which is available directly from the DVD company Madman. (Note that although there is no region coding, it is in the PAL format.)

When I was studying film in graduate school, Ernst Lubitsch’s German period was known mainly for the 1919 historical epic Madame Dubarry. There was little known about the two comedies that came out that year, perhaps the most amusing and delightful of all his German films in this genre: Die Austernprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” though seldom called by that title) and Die Puppe (“The Doll,” also a little-used name).

It’s hard to choose which of these three is Lubitsch’s best for the year. Ironically Madame Dubarry isn’t watched much any more, and it’s not on the recent DVD set “Lubitsch in Berlin,” though the two comedies are. Complete prints are rare, due in part to censorship. (If the print you see ends with a close-up of the heroine’s head held up after she is executed, you’ve probably been watching a reasonably complete version.) It may seem a bit stodgy upon first viewing, but I warmed up to it during repeated screenings while researching my book on Lubitsch’s silent films. There are many excellent moments: the extended series of eyeline matches when Louis XV first sees Jeanne, the masterfully timed and staged long take when Choiseul refuses to let Jeanne accompany Louis’s coffin, and a meeting among the revolutionaries that ends as Jeanne reacts in horror to their bloodthirsty plans, backing dramatically into shadow in the background (below).

Given how different these films are, I’m going to declare a tie between Madame Dubarry and one of the comedies. Wonderful though The Oyster Princess is, I’m opting for Die Puppe (above). Its story-book opening and stylization are charming. The hilarious scenes in the doll workshop and the monastery full of greedy monks fill out the plot, making it considerably denser than that of Die Austernprinzessin.

As with Lubitsch, when I was first studying film and for many years thereafter, Swedish director Mauritz Stiller was known mainly for one film, Sir Arne’s Treasure (Herr Arnes Pengar), though an abridged version of The Saga of Gösta Berling also circulated. Sir Arne’s Treasure was assumed to be his masterpiece. The gradual rediscovery and restoration of other Stiller films from the 1910s has considerably broadened our view of him. Perhaps Sir Arne’s Treasure is not the solitary, towering masterpiece it was long thought to be. Still, it holds up well upon revisiting.

It is a period piece set in a small seaside community. A group of foreign men massacre most of a family, in search of their mythical riches. They are forced to remain in the village when the ship in which they are to sail becomes  icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

Sir Arne’s Treasure was one of the films which gained the Swedish cinema of the 1910s the reputation for brilliantly exploiting natural landscapes. Few silent films have exploited actual winter settings so well. The actors are clearly working in genuine snow; one can sometimes see their breath fog as they speak. Atmospheric shots show the wind sweeping snow across the ice. Stiller uses the blank backgrounds created by the snow to create stark, simple compositions of dark figures and objects.

Kino’s DVD release uses a print from Svensk Filmindustri’s own archives. To my eye, the tinting used is too dark, especially since much of the action naturally takes place in the dark of the northern winter days. Deep blues somewhat obscure parts of the action. Still, the darkness adds to the brooding tone that pervades the story.

Erich von Stroheim’s first film, Blind Husbands, is the only one he completed that has come down to us in more or less its original version. As the director’s artistic ambitions expanded, his studios’ willingness to accommodate the growing  length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

Blind Husbands is my favorite among von Stroheim’s films. It tells its story of sin and punishment with a lighter touch than his later films would. The director plays a would-be seducer of a neglected wife when the group converges in a village for a mountain-climbing vacation. Von Stroheim’s eye for striking compositions against the snow-clad landscapes and his skillful use of the inn’s hallways and doors to convey the characters’ shifting relationships show an already mature grasp of the art form. (See right, where the villain eyes the heroine in her room but is himself watched by the protective guide in the hallway between the rooms.)

Maurice Tourneur’s Victory runs a mere 63 minutes in its current version, but the original footage count suggests that what we have is substantially complete. That’s somewhat short for a feature by a major director at this point in history, but the simple, intense plot, based on a Joseph Conrad short story, benefits from the compression. The protagonist is a man who has escaped his past and lives as a virtual hermit on a South Seas island. Attracted despite himself, he befriends a young woman playing in a visiting orchestra and rescues her from the abuse of the orchestra’s owner and the lustful advances of the local hotel owner. Returning with the woman to his lonely island, he faces the intrusion of three thugs deceived by the vengeful hotel owner into thinking that the hero has riches hidden on his island.

By this point Tourneur has fully mastered the “rules” of classical continuity style and of three-point lighting. Many of the compositions in Victory look like they could have been made in the 1930s. When I first saw the film about thirty years ago, I found the earliest case of true over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot that I had ever seen:

Since then, David has found an earlier one that sort of qualifies (maybe more on this in an upcoming entry), but this is a purer case.

Tourneur had also developed a distinctive approach to filming settings in long shot with framing elements within the mise-en-scene and figures silhouetted in the foreground (see top). In general the lighting is superb. Few Hollywood directors had reached this level of sophistication by 1919.

Victory has been released on DVD largely because it features Lon Chaney as one of the thugs. Image offers it paired it with another Chaney film. For some reason the titles are out of focus, but the rest of the film fortunately is in good condition and presents Tourneur’s visual style well.

DB’s picks:

Carl Theodor Dreyer began his film career writing scripts at the powerful Danish studio Nordisk. When he started directing, however, World War I had destroyed Nordisk’s markets, and the American cinema was on the rise. Dreyer’s generation was the first to register the impact of the emerging Hollywood cinema, and he displayed his understanding of Griffithian technique in The President (Praesidenten).

The English title should probably be something like “The Head Magistrate” or “The Presiding Judge,” and the plot appropriately sets up a tension between justice and personal obligation. One of Nordisk’s favored genres was the “nobility film,” in which illicit passion plunges a wealthy man or woman into the lower depths of society. Dreyer gave the studio a nobility film squared, using flashbacks to show how two generations of men in a family have seduced working-class women. The present-day drama displays the crisis that ensues when a respected judge realizes that the woman to be tried for infanticide is his illegitimate daughter. Dreyer’s abiding concern for the exploitation of women under patriarchy begins in his very first film.

From the early 1910s, Danish films displayed a mastery of tableau staging and careful pacing. But The President bears the mark of American technique in its bold close-ups and reliance on editing to build up its scenes. (There are nearly 600 shots in the film, yielding a rate of about 8.8 seconds per shot—quite swift for a European film of the era.) Perhaps more important are Dreyer’s efforts to shove aside the heavy furnishings of bourgeois melodrama. Compare the overstuffed set of Hard-Bought Glitter (Dyrekobt Glimmer, 1911) to this daringly bare one, with its sweep of cameos.

In the late teens, other Danish directors were moving toward simpler settings, but The President carries this tendency to geometrical extremes. Dreyer’s walls, bare or starkly patterned, isolate the players’ gestures and heighten moments of stasis. The result is one of the most adventurously designed film of its time, and if some of its experiments do not quite come off, already we can see that impulse toward abstraction that would be given full rein ten years later in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. The all-region DVD from the Danish Film Institute provides a somewhat dark tinted copy with original intertitles and English translations.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

A prologue shows lumbering, somewhat thick-headed Ingmar climbing a ladder to heaven, where generations of Ingmars sit in dignity around a massive meeting-room (see below). There his father tells him that he must find a wife. But Ingmar then explains that he once took a wife, with unhappy results. Some long flashbacks ensue, showing Ingmar forcing a young woman to marry him. The plot takes some doleful turns, with the result that the woman is sent to prison.

Running over two hours (and initially released in two parts), Sons of Ingmar has a fittingly lengthy climax that portrays the pains of reconciliation between a sensitive woman and an inarticulate man. In the film’s final scenes, Sjöström risks a delicate emotional modulation that would daunt a director today. Using Hollywood continuity cutting with a casual assurance, he relies on subtly timed cuts and changes of shot scale to trace the couple’s wavering guilts and hopes. These last scenes have a human-scale gravity that balances the weighty paternal authority of the heavenly sequences. In Theatre to Cinema our colleagues Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster have written a penetrating analysis of the performances of Sjöström as Ingmar and Harriet Bossa as Brita.

Unhappily, we know of no video version of this wonderful film. It should be a top priority for DVD companies specializing in silent cinema.

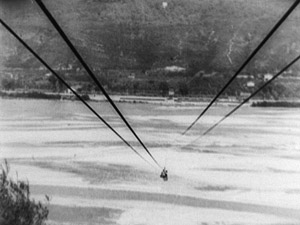

Another 1919 candidate for ambitious DVD purveyors is Louis Feuillade’s great serial Tih Minh. It has been overshadowed by Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), and Judex (1917), but it has a playful charm of its own. It is, in a way, the anti-Vampires. Instead of chronicling the triumphs of an all-powerful secret society, this six-hour saga gives us a few ill-assorted conspirators who inevitably fail at every scheme they try. The plot is no less far-fetched than that of the earlier serial, but the twists are more comic than thrilling. (Which is not to say that we’re denied some astonishing real-time stunt work performed by the actors, as above.) The film’s genial tone assures us that nothing bad will happen to the poor girl Tih Minh, but the villains will get enjoyably harsh punishment. In the course of the adventure three couples are formed, the routines of provincial life are filled in with leisurely detail, and the whole thing ends with a big wedding.

Unlike the Paris-bound serials, Tih Minh allowed Feuillade to apply his elegant staging skills to natural landscapes. By now he was filming in Nice, and the chases and fistfights are enhanced by gorgeous mountains, vistas of water, and hairpin roads. More than one connoisseur has confessed to me that this is their favorite Feuillade serial, and it’s hard to disagree. I always find that viewers are carried away by its zestful tale of good people who come to a good end.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

KT’s runners-up: I suppose that there will be some tongue-clicking over the fact that Abel Gance’s J’accuse! is not present in our list. There’s no doubt it’s historically important and influential, but it’s also heavy-handed and doesn’t add the leavening of humor to its melodrama, as some of the above films do. But it does deserve a mention in an overview of 1919. (I’ve posted about what I see as Gance’s limitations here.)

Last year I put Marshall Neilan’s Mary Pickford vehicle, Stella Maris, in the top ten. I’d be tempted to do the same with his (and her) Daddy-Long-Legs, but this year there’s a lot more competition. But it’s a charming film, and the great cinematographer Charles Rosher provides another series of beautiful images using the new three-point lighting system. It was the first Pickford film into Germany after the war and considerably influenced Lubitsch and other German directors.

Similarly, in a year with fewer major films, Victor Fleming’s When the Clouds Roll By, a wacky, inventive tale of superstition and psychological manipulation starring Douglas Fairbanks, would make the main list. David illustrated some of that inventiveness in his epic entry on Fairbanks.

Within a few years, compiling our 90-year picks will become increasingly difficult. Experimental cinema will blossom, as will animation. The Soviet Montage and German Expressionist movements will get started, and French Impressionism, still a minor trend in the late teens, will expand. Filmmakers like Murnau, Lang, Vidor, and Borzage will gain a higher profile, and more films by veteran directors like Ford will survive. Maybe we’ll have to expand the annual list even further. . . .

A very happy New Year to all our readers! Assuming we make it through the security lines, we shall be celebrating New Year’s Eve on a plane bound for Paris, where David will be doing a lecture series over the first few weeks of January. Paris is the world capital of cinema, at least as far as the diversity of films on offer goes, so we shall no doubt find occasion to blog while there.

Sons of Ingmar.

The ten best films of . . . 1918

Kristin here–

We ended 2007 with a salute to the 90th anniversary of the solidification of the classical Hollywood filmmaking system. 1917 was not only the year when all the guidelines—continuity editing, three-point lighting, and unified story structure—gelled in American cinema. It was also one of those years (like 1913, 1927, and 1939) when a burst of creativity took place internationally. For those years, it’s hard to keep one’s greats list to ten.

Enough of you enjoyed that entry that we thought we would come up with another list to end 2008. For some reason, 1918 doesn’t yield the plethora of great films that obviously should go on such a list. Maybe it’s the sheer accident of preservation. After a string of masterpieces from Douglas Fairbanks in 1917, there seems to be a dearth of his films extant from the following year. Some filmmakers, like Cecil B. De Mille, simply released fewer films in 1918. And of course, some masterpieces may still lie gathering dust on archive shelves, waiting to be discovered.

Still, great films were made that year, some familiar—some that should be better known. Some are available on DVD, and some are excellent candidates for release by some of the enterprising companies like Kino International, Image Entertainment, and Flicker Alley.

1. The list isn’t in rank order, but for me the outstanding film of 1918 is Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru, better known to most as The Outlaw and His Wife, by Victor Sjöström. This tale of an enduring love between a man  hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

This year Kino also brought out a disc with the dynamite double bill of two tragedies Ingeborg Holm (1913) and Terje Vigen (1916). David and I have both written about the staging in Ingeborg Holm, and David has had much to say on tableau staging in 1910s cinema. Watch these three films, and you will understand why we consider Sjöström perhaps the great director of the decade. It’s a shame that more of his films are not available yet in the U.S. Buy copies of these, and maybe Kino will bring more of them out.

2. Another master of this era, Louis Feuillade, made a sequel to his Judex (1916): La Nouvelle Mission de Judex. David discusses both in the second chapter of his Figures Traced in Light. Although Judex is available on DVD, so far the second serial is not.

3. I suspect that Hearts of the World is one of those D. W. Griffith features that a lot of film enthusiasts have heard of but not seen. Remarkably, it’s not available on DVD. (Keep your old laserdisc if you’ve got one!) I have to admit, it’s not one of my favorite Griffiths, though it does have a charming performance by Dorothy Gish and contains scenes that were actually shot near the front lines in France.

4. Ernst Lubitsch was making the transition from shorts to features in 1917 and 1918. While Carmen is historically important for his development toward his mature style, most audiences these days would probably find Ich möchte kein Mann sein (“I don’t want to be a man”) more entertaining. It’s a comedy about an independent young lady who escapes her strict governess and guardian by going out on the town disguised as a man—in the process joining her guardian without his recognizing her (see the frame at the bottom). Its star, Ossi Oswalda, was an outgoing blonde dynamo, quite different from Pola Negri, whom Lubitsch turned to for his later historical epics.

Kino has made several of Lubitsch’s films from the late 1910s and early 1920s available. Ich möchte kein Mann sein can be bought on a single disc with Die Austerinprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919), another Oswalda comedy. I’d recommend getting it as part of the larger “Lubitsch in Berlin” set, which also includes the hilariously imaginative Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919), the Expressionist satire Die Bergkatze (“The Wildcat,” with Negri in her one comic role for Lubitsch, 1921), an Arabian-nights epic Sumurun (1920), and the historical epic Anna Boleyn (1921), as well as a documentary on Lubitsch.

5. In 1918 Cecil B. De Mille made a film that would change his career’s trajectory: Old Wives for New. At the  time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

6. Hell Bent, by John Ford, was long thought to be among his many lost westerns from the early years of his career. It was rediscovered in the Czechoslovakian archive and shown years ago in Pordenone at the Il Giornate del Cinema Muto festival. I must confess that I don’t remember it very well, apart from one spectacular tilt downwards as a stagecoach (?) races down a winding mountain road. Not as good as Straight Shooting, and Hell Bent survives in rocky shape (perhaps too much so for DVD release), but Ford films of this era are so rare that I’ve listed this one.

7. Like Lubitsch, in the late 1910s Charlie Chaplin was making a gradual transition from shorts to features. In 1916 and 1917 he released a remarkable string of Mutual two-reelers, from The Rink (December 1916) to The Adventurer (October 1917). In 1918, with A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, he increased the films’ length to three reels, or roughly 45 minutes, and started releasing through First National. He also cut back on the number of titles released each year. Apart from a brief promotional film for war bonds, A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms were his only 1918 releases. Which is better? I suppose most people would say Shoulder Arms. To me it’s a toss-up.

8. David and I started attending Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1986, when the festival was launching its great series of national retrospectives. In quick succession, these retrospectives revealed three hitherto virtually unknown but major auteurs of the 1910s: the Swede, Georg af Klercker, in 1986; the Russian, Evgeni Bauer, in 1989; and the German Franz Hofer, in 1990. Bauer’s career ended with his death in 1917. Hofer remained active until the early 1930s. The Giornate’s German program contained only six of his films, however, and those from the 1913-1915 period. I suspect that means the later teens titles are lost.

In contrast, nearly all of af Klercker’s films survive, mostly in the original negatives. The prints shown at Pordenone were stunning. The director had a great eye for settings, using beaded curtains, mirrors, and other elements to considerable effect. He made three films in 1918: Fyrvaktarens dotter, Nobelpristagaren,Nattliga toner, the first two of which were shown in the 1986 retrospective.

Unfortunately since then the films have not been made widely available, either in prints or on DVD. Having not seen the two titles just mentioned since 1986, I can’t say that I remember them well enough to judge between them. So I’ll just leave all three films here, along with the advice to seize any chance you may get to see those or af Klercker’s other films.

(Given how little known af Klercker’s work is outside Sweden, I should point out a major English-language piece on the director’s style, Astrid Söderbergh Widding’s “Towards Classical Narration? Georg af Klercker in Context,” in editors John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930 [Sydney: John Libbey, 1999].)

9. Stella Maris, directed by Marshall Neilan, was the first of five features Mary Pickford starred in in 1918. Its reputation lies mainly in the fact that Pickford played a double role, the bed-bound but lovely title character, and an ugly, slightly deformed orphan. In its outline, the story sounds abstract and overly symmetrical. Stella Maris’s relatives shut her off from all ugliness in the world, keeping her in happy innocence well into her teens. Unity, the orphan, has known nothing but deprivation. As Stella comes to glimpse the grim side of life, Unity is adopted and has glimpses of the beauties enjoyed by the rich. Both become miserable as a result.

The overall implication is pretty grim. Stella’s world is initially wonderful only because everyone lies to her. She becomes embittered when she finally discovers this. At the heart of the tale is the deception that life is beautiful. Unity, who has not been deceived, knows better from the start. Even one brief reference to the war, as a troupe of soldiers passes by the estate where Stella lives, makes it seem tragic—this in a film that came out about two months after the U.S. had entered World War I.

The balance between the two characters is made less artificial than it might sound by Pickford’s extraordinary performance—not so much as Stella, who is a rather passive version of the typical Pickford persona, but as Unity. The waif’s frequent disappointments and outright suffering create a strong effect that shadows even the quasi-happy ending. It’s a beautifully made film as well, with the use of glamorous backlight (as in the image at the top of this entry). Stella Maris is available on DVD from Image.

10. I have been hard put to find a feature to round out the list, so I’m substituting a group of shorts. They’re not masterpieces by any means, but each displays the talents of a great silent comic well on the way toward his most fruitful period.

There’s no single great film to mark Harold Lloyd’s transition, but during 1918 he was developing his “glasses” character. He had had a modest success with his “Lonesome Luke” series from 1915 to 1917, where he essentially created a variant of Chaplin. In September, 1917, Lloyd first wore his famous black, lens-less glasses in Over the Fence. His early one-reelers wearing those glasses were still sheer slapstick, with little of the characterization that he would later develop to go with his new look. Arguably it was 1919 or even 1920 before he had fully nailed that persona. Still, during 1918 one can see him groping toward the formula.

Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection” volumes contain four films from that year, all co-starring Lloyd’s  regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

1917 and 1918 formed the high point of the string of comic shorts directed by Fatty Arbuckle, in which he also co-starred with Buster Keaton and Al St. John. When Keaton went solo, he proved to be a far better director than Arbuckle. Arbuckle tended to simply face his camera perpendicularly toward the back of the set for every shot, just cutting to whatever scale of framing would best display a gag. Here it’s the perfectly timed and executed gags that dazzle, and the films are often hilarious. In 1918, the team made The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Out West, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook. The latter shows off Arbuckle and Keaton’s dexterity at juggling props and Fatty’s surprising grace, as when he improvises a Salome dance with a head of lettuce standing in for that of John the Baptist!

The 13 surviving Arbuckle-Keaton films (some with missing bits) are available on Eureka’s definitive boxed set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films.” (That’s Region 2 format only, and available from Amazon UK.) Image’s “The Best Arbuckle Keaton Collection” has 12 films, missing only the more recently rediscovered The Cook. Image brought out The Cook on a disc with Arbuckle’s A Reckless Romeo (1917, sans Keaton). Kino’s two separately available volumes of “Arbuckle & Keaton” (here and here) contain 10 shorts total, again missing The Cook.

Apart from all these films, it’s worth noting that in the world of animation, 1918 saw the release of Winsor McCay’s fourth cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania, and Dave Fleischer’s first, Out of the Inkwell, which launched the enduring series.

Next year, 1919. Happy 2009 to all our readers!

Happy birthday, classical cinema!, or The ten best films of … 1917

Wild and Woolly (1917).

KT:

Periodization is a tricky task for historians, and there are a lot of disputes about how to divide up the 110-plus years of the cinema’s existence. We all have to deal with it, though, if we want to organize our studies of the past into meaningful units. How to do that?

Do we divide the periods of film history according to major historical events? World War I had a huge impact on the film industry, to be sure, and we might say that one significant period for cinema is 1914-1918. Yet 1919 didn’t mark the start of a new period. The major European post-war film movements didn’t start then. French Impressionism arguably began in 1918, German Expressionism in 1920, and Soviet Montage in 1924 or 1925.

Carving up film history partly depends on what questions the historian is asking. If you’re studying wartime propaganda, 1914 and 1918 would provide significant beginning and end points. If you want to trace the development of significant film styles, it doesn’t seem very useful.

While historians have difficulties agreeing on periodization, just about everyone concurs that there were two amazing years during the 1910s when filmmaking practice somehow coalesced and produced a burst of creativity: 1913 and 1917.

One can point to stylistically significant films made before 1913. Somehow, though, that year seemed to be when filmmakers in several countries simultaneously seized upon what they had already learned of technique and pushed their knowledge to higher levels of expressivity. “Le Gionate del Cinema Muto” (“The Days of Silent Cinema”), the major annual festival, devoted its 1993 event to “The Year 1913.” The program included The Student of Prague (Stellan Rye), Suspense (Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber), Atlantis (August Blom), Raja Harischandra (D. G. Phalke), Juve contre Fantomas (Louis Feuillade), Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni), Ingeborg Holm (Victor Sjöström), The Mothering Heart (D. W. Griffith), Ma l’amor mio non muore! (Mario Caserini), L’enfant de Paris (Léonce Perret), and Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (Yevgenii Bauer). .

1917, by contrast, was primarily an American landmark. As 2007 closes, we thought it appropriate to wish happy birthday to the most powerful and pervasive approach to filmic storytelling the world has yet seen. That would be classical continuity cinema, synthesized in what was coming to be known as Hollywood.

DB:

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema and work we’ve done since, we’ve maintained that 1917 is the year in which we can see the consolidation of Hollywood’s characteristic approach to visual storytelling. This idea was first floated by Barry Salt, and our research confirms his claim. Over the ninety years since 1917 the style has changed, but its basic premises have remained in force.

Before classical continuity emerged, the dominant approach to shooting a scene might be called the tableau technique. Action was played out in a full shot, using staging to vary the composition and express dramatic relationships. Elsewhere on this site I’ve mentioned two major exponents of this approach, Feuillade and Bauer.

When there was cutting within the tableau setup, it usually consisted of inserted close-ups of important details, especially printed matter, like a letter or telegram. Occasionally the close-up of an actor could be inserted, usually filmed from the same angle as the master shot. The tableau approach was more prominent in scenes taking place in interiors; filmmakers were freer about cutting action occurring outdoors.

We shouldn’t think of the tableau as purely “theatrical.” For one thing, the master shot was typically closer and more tightly organized than a scene on the stage would be. Moreover, for reasons I discuss in Figures Traced in Light, the playing space of the cinematic frame is quite different from the playing area of the proscenium theatre. The filmmaker can manipulate composition, depth, and blocking in ways not available on the stage.

The tableau approach was the default premise of US filmmaking through the early 1910s. You can see it at work, for example, in this shot from At the Eleventh Hour (W. V. Ranous, 1912). Mr. and Mrs. Richards are in the study of Mr. Daley. After Richards has refused to sell his railroad bonds, Daley’s wife shows off her diamond necklace to the visitors.

At first the two couples are separated in depth, the men in the foreground and the women further back. In the first frame below, a new necklace has just been delivered, and a servant gives it to Mrs. Daley. Only the servant’s hand is visible, as she is blocked by Richards in the foreground. In the second frame, the two women come forward. Mrs. Daley holds the necklace up and Mrs. Richards oohs and ahhs over it, while her husband glances at Daley as if to wonder how he could afford it.

Instead of breaking the scene into closer views, spreading the characters’ reactions across separate shots, Ranous squeezes all of their actions and expressions into a tight space across the center of the shot. Nor does he provide a close-up of the necklace, which will be important in the plot. (1) We might be inclined to say that this is a “theatrical” shot, but on a stage the actions in depth (the women chatting, the servant handing over the parcel) wouldn’t be visible to everyone in the auditorium. Likewise, on a stage the packed faces in the later phase of the scene wouldn’t be visible to people sitting on the sides.

As films became longer, American filmmakers were starting to organize their plots around characters with firm goals. Conflicting goals would set the characters in opposition to one another, and at a climax, usually under the pressure of a deadline, the protagonist achieves or fails to achieve the goals. The plot also tends to build up two lines of action, at least one involving romance.

There’s no reason this conception of narrative could not have been applied to the tableau style; in many cases it was. But hand in hand with the rise of goal-driven plotting came a new approach to filming. Sporadically before 1917, filmmakers in many countries were exploring ways to build scene out of many shots. (If you want to know the process in the US in more detail, check out Early American Cinema in Transition by Charlie Keil.) By 1917, American filmmakers had synthesized these tactics into an overall strategy, a system for staging, shooting, and cutting dramatic action.

We know the result as the 180-degree system. This encourages the filmmaker to break a scene into several shots, taken from different distances and angles, all from one side of an imaginary line slicing through the space. Around 1917, this stylistic approach comes to dominate US feature films, in the sense that every film made will tend to display all the devices at least once. The system remains in place to this day, and it came to form the basis of popular cinemas across the world. (2)

Once you break a scene into several shots, some characters won’t be onscreen all the time. So you need to be clear about where offscreen characters are; you need to supply cues that allow the audience to infer their positions. So 1910s filmmakers developed various ways of “matching” shots.

Shots can be connected by character looks, thanks to the eyeline match. Here’s an instance from Victor Schertzinger’s The Clodhopper (1917). First there is a master shot of the mother and son in their farm kitchen.

This is followed by a separate shot of each one. Their bodily positions and eyelines remind us that the other is just out of frame.

Although over-the-shoulder shooting hadn’t yet been developed, a conception of the reverse angle is at work here too. Schertzinger’s camera doesn’t shoot the actors perpendicularly, but takes up an angle on one that becomes an echo of that filming the other. Here’s another example of reverse angles from The Devil’s Bait (1917, director Harry Harvey).

The camera doesn’t just enlarge a portion of the space, as in the inserted shot in a tableau scene. The angle of view has changed significantly.

Changes of angle within the scene have become fairly complex by 1917. This strategy is apparent when the action takes place in a theatre, a courtroom, a church, or some other large-scale gathering point. The camera position changes often in this scene from The Girl without a Soul (director John Collins).

The concept of matching extends to physical movement too, through the match on action. This device allows the director to highlight a new bit of space while preserving the continuity of time. In Roscoe Arbuckle’s The Butcher Boy, the cut-in to Fatty (with a change of angle) also matches his gesture of putting his hands on his hips.

Interestingly, even this early, directors have learned to leave a little bit of overlapping action across the cut. If you move frame by frame, you’ll see that Fatty’s gesture is repeated a bit at the start of the second shot.

When a character leaves one frame, he or she can come into another space, from the side of the frame consistent with the 180-degree premise. This is matching screen direction. A cut of this sort lets us know that the next portion of the locale that we see is more or less adjacent to the previous one. In Field of Honor (director Allen Holuban), Wade crosses to Laura, who’s waiting in a carriage. A few years earlier, the director might have presented his greeting in a single deep-space long shot. Instead, Wade exits one shot and enters the next.

Again, the reverse-angle principle governs the camera setups. Wade moves along a diagonal toward the camera and away from it.

More generally, Field of Honor exhibits a polished handling of the new style: lots of reverse shots and eyeline matches, fades that bracket flashbacks, binocular points of view, rack-focus shots, and rapid cutting (there’s even a ten-frame shot). The point is not to claim Field of Honor as an undiscovered masterpiece but rather to indicate that by 1917 a director could handle all the devices with assurance.

Match-cutting devices had been used occasionally before 1917, but by that year filmmmakers melded them into a consistent and somewhat redundant method of guiding the audience through each scene.

The continuity system not only creates a basic clarity about characters’ positions. It can as well generate a speed and accentuation not easily achieved within a single shot. For example, Wade’s frame exit and entrance above is cut so as to skip over moments that he consumes crossing the driveway. Continuity editing enhances the rapid pace of US films, a quality immediately noted by foreign observers in the 1910s and 1920s.

Two of the best films of 1917 exploit the dynamism of continuity cutting. The Doug Fairbanks comedy western, Wild and Woolly, seems designed to prove that American films could proceed at breakneck speed. In climactic scenes, we’re caught in a whirlwind of fast cutting, with the pace set by the hyperactive protagonist, a financier’s son who longs to prove himself as a cowboy.

John Ford’s Straight Shooting proceeds at a more measured pace, but in its final shootout we see a prototype of all the main-street gundowns that will define the Western. Ford provides alternating shots of the cowboys advancing toward each other, framing each man more tightly and concluding with suffocating close-ups of each man’s face, highlighting the eyes.

Sergio Leone, eat your heart out.