Archive for the 'UW Film Studies' Category

Magic, this Lantern

Home page of Lantern (top half).

DB here:

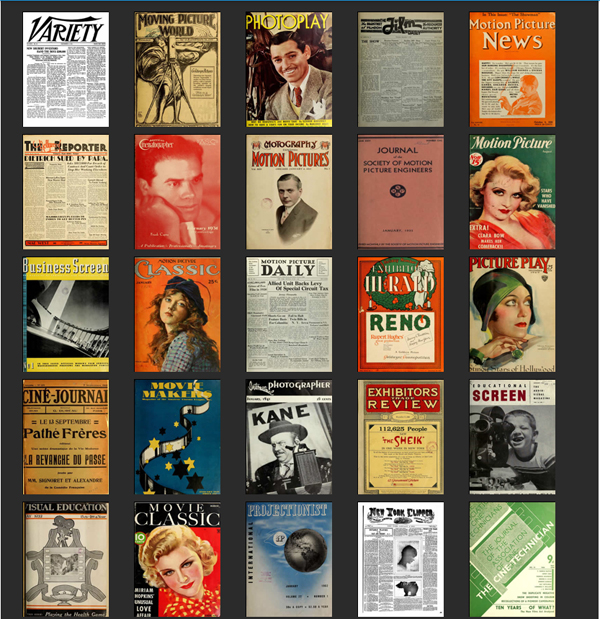

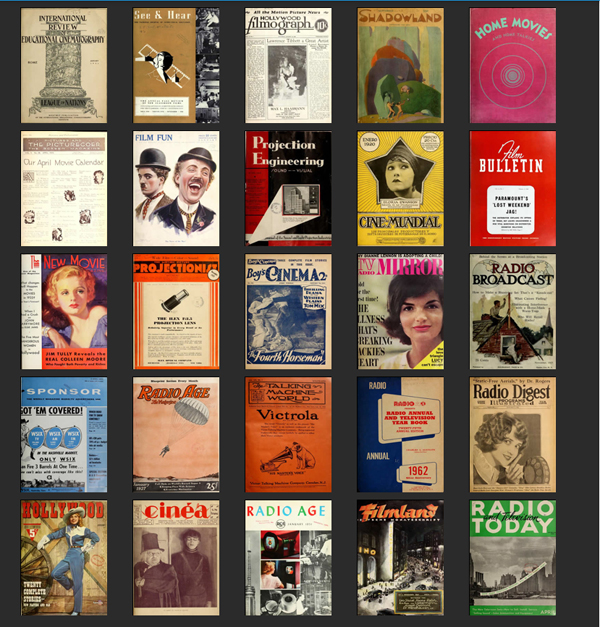

In earlier entries (here and here) we’ve reminded you of the immense and growing resource that is the Media History Digital Library. It was founded and is directed by David Pierce, world-renowned moving-image archivist, and it’s co-directed by UW-Madison Communication Arts professor Eric Hoyt. If you haven’t wandered, or rushed, or hop-skipped, through this wondrous library devoted to images and sounds, you owe it to yourself to start.

Of course it’s a remarkable resource for historians of film, television, and radio. It gathers a huge number of periodicals that can be searched, read, and downloaded–gratis. Thanks to its hookup with the Internet Archive, you can access and own entire books. The tireless Catherine Grant gives us Film Studies for Free. David and Eric give us Film History for Free.

But it isn’t just professional and amateur researchers who benefit. Anyone even mildly curious about media in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries should take the time to browse through the fan’s paradise that is Photoplay, the show-biz churn of Variety, the techie wonderland that is Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers and International Projectionist and many other publications. I guarantee you will be surprised and delighted by what you find: Big pages, beautifully displayed, that can hold you, we might say, spellbound; or at least make you girl crazy.

Why have you held back? Perhaps the sheer number of collections was daunting. And previously you had to search each journal separately, year by year.

Now Eric and his team, many here at UW, have made things even easier for historians and civilians alike. Today the MHDL crew have unveiled their new super-search engine, Lantern. Lantern allows you to search all of the MHDL publications at one go. Apart from the massive efficiency, you discover sources you wouldn’t have thought to check.

If you’re bold and type in Chaplin, for instance, you get 1446 hits. Many of them are from books, thanks to the generosity of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, Jeff Joseph, and many contributors to the Internet Archive. I struck minor gold with my first hit, a page from Charlie’s 1922 travel memoir My Visit:

Dear Mr. Chaplin: You are a leader in your line and I am a leader in mine. Your specialty is moving pictures and custard pies. My specialty is windmills. I know more about windmills than any man in the world. . . . You have only to furnish the money. I have the brains, and in a few years I will make you rich and famous.

A search for Gregg Toland brings you not only his much-reprinted 1941 American Cinematographer article, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” but also many AC articles featuring professional discussion of his contributions–not all of them complimentary. “Pan-focus…,” notes one, “may be a flash in the pan.” An anonymous review of The Little Foxes complains that in some shots “The eye hardly knows where to look.” But go beyond AC and you find lesser-known treasures: articles by Kane’s on-set still photographer, a different piece by Toland (opposite a full-page topless young lady), and 52 more. That’s just in 1941.

A search for Gregg Toland brings you not only his much-reprinted 1941 American Cinematographer article, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” but also many AC articles featuring professional discussion of his contributions–not all of them complimentary. “Pan-focus…,” notes one, “may be a flash in the pan.” An anonymous review of The Little Foxes complains that in some shots “The eye hardly knows where to look.” But go beyond AC and you find lesser-known treasures: articles by Kane’s on-set still photographer, a different piece by Toland (opposite a full-page topless young lady), and 52 more. That’s just in 1941.

Yes, while the default search digs for everything, you can limit your search by year and along other parameters.

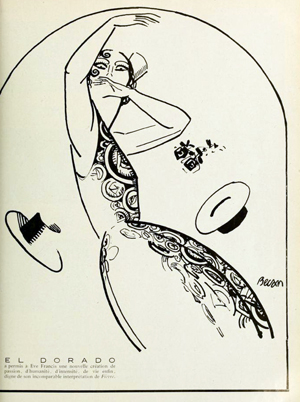

Lest you think that this bounty is of interest only for followers of Hollywood, please note that the Global Cinema collection (1904-1957) includes books and periodicals from France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Spain, and the United Kingdom. In 1921, for instance, Louis Delluc’s magazine Cinéa, while badmouthing Feuillade fairly constantly, gives unflagging support to L’Herbier’s El Dorado and adds in this sprightly caricature of Eve Francis.

Not all the collections are complete. There are of course copyright constraints on recent publications, and some journals are so rare that the runs must be filled in as copies are found. But the MHDL, like the universe, is constantly expanding, and possibly faster. Soon to be added are Quigley’s Exhibitors Herald, Cine-mundial, and more years of Variety. This spectacular enterprise is in the hands of people who are utter and dedicated completists.

I hate to pull a Grandpa Simpson, but when I think of all the time and money and gasoline and air tickets I ran through over several decades to visit libraries holding a few issues of this or that journal . . . and then think about the hours I spent paging through them looking for certain names, terms, film titles . . . and then think about how I painstakingly copied what I wanted onto 3 x 5 cards (photocopy not permitted) . . . I think–Well, what do you think I think?! I think how damn lucky you (and I) are to have all this material so accessible now. For work and play.

Same thing, come to think of it.

Thanks to Eric Hoyt for giving me a quick preview of Lantern, and to all my colleagues at UW-Madison who are supporting this remarkable undertaking. You can too: donations gratefully accepted.

P. S. 15 August 2013: Eric provides some helpful tips for using Lantern at the UW-Communication Arts blogsite Antenna.

Home page of Lantern (bottom half).

Industrial strength

Edith Head costume sketch for To Catch a Thief. From Edith & Oscar: A Costume Exhibit, WCFTR website.

DB here:

Until the 1970s, academics interested in film seldom paid close attention to Hollywood as an industry. Some economists and historians of law were beguiled by the sight of an oligopoly eventually dismantled by Supreme Court decree. But these scholars weren’t particularly interested in the products of the studio system.

People interested in the movies took three positions. The most dogmatic, voiced by one of my grad-school professors, ran this way: “Money doesn’t matter.” That is, art will always triumph over business. If a movie is good, the circumstances of its making are irrelevant. And we study only good movies, so we needn’t consider the business.

Another view acknowledged the importance of the industry but saw it as a vague, overarching force. Creative artists were seduced by it or struggled against it. A powerful director like Chaplin or Hitchcock could control his work to a considerable degree. For the less powerful, the studios (along with censorship agencies) were barriers to creative work. They forced directors to bow to the demands of moguls or a debased public.

The third view was largely celebratory. The studios represented a wondrous confluence of talent at every level, from script to music, and the System mysteriously spun out marvels of drama, comedy, and spectacle: Hollywood as Gollywood. Researchers in this tradition ferreted out as much information as they could about the old days, infusing encyclopedic ambitions with fan enthusiasm.

What came to be called “Wisconsin revisionism” or “the Wisconsin Project” proposed some alternatives.

Auteurist in the archive

Corner of WCFTR office area. Photo: Mary Huelsbeck.

When I came to UW–Madison to teach in 1973, I was an auteurist with a taste both for Hollywood and foreign cinema. I knew relatively little about how the studio system functioned. Its machinations were simply factored out of my consideration. Directors, from Hitchcock and Hawks to Dreyer and Mizoguchi, were what loomed in my consciousness, and I wanted to spend my life studying what they had accomplished.

But contact with students, faculty, and campus personalities at Madison changed my thinking. There was The Velvet Light Trap, a defiantly unofficial magazine that ran special issues on all manner of non-auteur subjects, especially studios, periods, and genres. There were ambitious film societies like Fertile Valley and the Green Lantern, showing offbeat items. There were smart, well-informed grad students. There was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which housed thousands of prints, the center of my lustful thoughts both day and night. The WCFTR also housed vast archives of papers, scripts, photos, and other documents of Hollywood’s golden era.

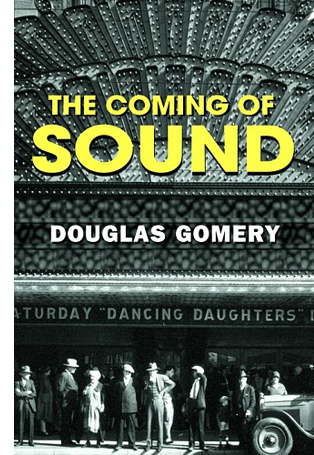

Then there were Professor Tino Balio and Dissertator Douglas Gomery. My conversations with them, both in and out of the office, showed me that there were fruitful questions to be asked about the nature and conduct of the studio system. These two scholars, I think, more or less invented the rigorous historical study of Hollywood as a business enterprise.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Tino, who was presiding over the WCFTR, became another premiere scholar of filmmaking as a business. His books, anthologies, and book series brought immense attention to our collection of material on United Artists, Warner Bros., and RKO. He taught courses in the history of the industry, both survey courses and in-depth seminars. I think I learned more sitting on examination committees with him than I had in many of my grad-school lectures.

Many of the research questions asked by Tino, Doug, and their peers didn’t concern the movies themselves. Some did, though. I remember Cathy Root’s study of stars as strategies of “product differentiation.” More broadly, in the 1970s and early 1980s, some of us suspected that the Hollywood system of production, distribution, and exhibition could affect what then was called “the film text.”

As a result, Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I tried to show how Hollywood’s mode of production did more than simply limit gifted artists or yield pop-culture diversions. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), we tried to understand how the organization of production shaped work routines, technology, adjacent institutions, conceptions of quality, and other factors that did impinge on how the films looked and sounded. Over the years these aspects of filmmaking practice took off on their own, becoming somewhat detached from the industrial conditions that created them. When the studio system faded away in its classic form, the community’s notions of narrative construction, stylistic expression, professional practices, and other factors hung on. The economics changed, but the aesthetics persisted.

Now there are many people working to show how industrial factors interact with filmmakers’ creative choices. Kristin and I have continued these explorations in books and blog entries, extending them to other periods (e.g., the 1910s, the New Hollywood, the 1940s). I like to think that much of our work over the last decades has tried to blend the careful empirical and explanatory work of Tino, Doug, and others with the analysis of art and craft typical of film criticism. We can ask some questions that cut across the over-simple Art/Industry split.

Let a thousand projects bloom (motto, People’s Republic of Madison)

This exercise in autobiography was triggered by some recent events. One is the spiffy new website for the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Under its recent director Michele Hilmes and current director Vance Kepley, the Center has gotten a new jolt of energy. It’s promoting its vast collections in an attractive way and is starting to spotlight some that weren’t well-known. The selections are bolstered by informative program notes by Maria Belodubrovskaya, Booth Wilson, and others.

Certainly the Center’s heart, for historians of Hollywood, is the United Artists collection. This assembles United Artists business records from 1919-1965, scripts and stills from Warner Bros. and RKO, and several thousand film features, shorts, and cartoons, mostly from 1928 to 1948. Then there are the hundreds of named collections, provided by individual donors. The refurbished website calls attention to several of them: the personal and business correspondence of Kirk Douglas (some items now digitized), the Blacklist collection (six of the Hollywood Ten represented), the dazzling array of Edith Head’s costume designs (okay, I’m going a bit Gollywood). There are records for Otto Preminger, Walter Wanger (the basis of Matthew Bernstein’s biography), and Shirley Clarke. The restored Portrait of Jason was discovered in her collection.

Lately, needing information on Guest in the House (1944), I turned to the WCFTR screenplay by Ketti Frings. Her name looks like a Scrabble hand, but she turns out to be a fairly significant screenwriter, contributor to The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), Dark City (1951), and By Love Possessed (1961). Some other day I must get around to prowling in the papers of Vera Caspary, an extraordinary person who is far more than the author of Laura (though I’d be happy just being that).

Beyond Hollywood, the Center holds major collections of Russian cinema and, more recently Taiwanese cinema. And if you must leave cinema behind for theatre, you can investigate Eugene O’Neill, George S. Kaufman, and many other luminaries. In sum, a resource to make you happy for decades.

A career and a conference

The expansion of the Center owes everything to Tino Balio, who served as director in its crucial years. It was he who acquired the UA treasures and many of the named collections. Access to the UA papers enabled him to write the definitive history of the company, but it also created a huge spillover effect: dozens of research projects were nourished by his pursuit of this collection—which came to us at a time when virtually no universities, not even those in LA, were seeking Hollywood corporate records.

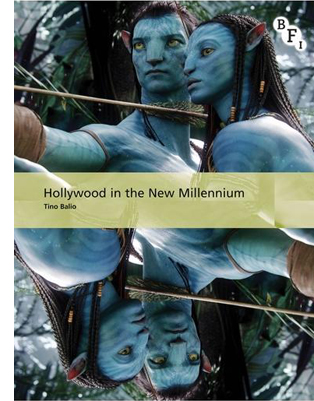

So it’s fitting that, as the WCFTR redesigns its public profile, we see the publication of Tino’s Hollywood in the New Millennium.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

Hollywood in the New Millennium charts the trends that characterize the last fifteen or so years of the American film industry. It surveys financing, production, distribution, exhibition, ancillary markets, and the independent realm. Tino analyzes the ways in which new technologies have changed all these areas, mostly to the benefit of the bottom line, but he also recognizes that technology can undermine the business, especially in the hands of what he calls “the I-want-it-for-free consumer.”

He surveys studio policies, attempts at synergy, and viral marketing. He traces the rise and fall of executives and is especially strong on the emergence of the overriding strategy of the tentpole picture aimed at teenagers and families. Since all studios belonged to entertainment conglomerates, the constant demand was for large-scale profits. For all its financial excesses, the tentpole strategy, Tino argues counterintuively, was an austerity measure.

By the decade’s end, every studio was in the tentpole business. Although the costs of producing and marketing such pictures were enormous, they were the only types that could perform on a global scale and generate significant returns. . . . The sure thing was a good hedge against a dying DVD business, the fragmentation of the audience, and the unknown impact of the internet and social media on Hollywood marketing practices.

In short, you could not ask for a more concise, reliable map of where Hollywood is today. The bibliography is expansive enough to inspire other researchers to dig into both printed and online sources.

Tino has exercised a remarkable influence on two generations of film scholars, but in an almost surreptitious way. Now every film student learns about the structure and conduct of the film industry, but few know that Tino played a pivotal role in making this sort of knowledge central to academic film study. Now in his mid-seventies, Tino has left a peerless legacy of research.

Speaking of research, our campus will be hosting a major conference that includes the WCFTR as a key component. The Screenwriting Research Network International is holding its annual gathering here on 20-22 August. I attended the Brussels SRNI conference two years ago and wrote about it here and here. I think it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all. This is a stimulating bunch, and anyone interested in filmmaking would benefit from attending.

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

The scholars are no less stellar and include Kathryn Millard, Richard Neupert, Jill Nelmes, Steven Maras, Riikka Pelo, Eva Novrup Redvall, Nate Kohn, Ronald Geerts, Andy Horton, Ian Macdonald, and a great many more. Go here for a complete program. You will be impressed.

Needless to say, among the guests are many UW alumni: Patrick Keating, Colin Burnett, Maria Belodubrovskaya (currently a faculty member too), Brad Schauer, Mark Minett, Mary Beth Haralovich, and David Resha. All of them have been steeped in archival research, centrally at WCFTR. Also home-grown are the conference organizers, J. J. Murphy (who blogs here) and Kelley Conway, who is finishing her book on Agnès Varda after immersion in that great lady’s personal archive. Another faculty member, Eric Hoyt, is curator of the remarkably full and free Media History Digital Library; expect him to divulge newer-than-new research sources and methods. I’ll crowd into the act with a paper tied to my 1940s book.

All in all, I see a pleasing continuity from my salad days, through forty years of teaching and viewing and writing, to this moment: a new Balio book, a sparkling shop window for the Center, and new generations of researchers eager to show that The Industry and The Art of Cinema aren’t always that far apart.

Earlier memoirs of Mad City culture in the 1970s-80s are here and here.

For more on the origins of Wisconsin revisionism, see my introduction to Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992) and this entry. We have a blog entry on Tino’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens here.

On the remarkable Vera Caspary (Wisconsin’s own) see not only her fine thrillers Laura and Bedelia but also her Bohemian autobiography The Secrets of Grown-Ups (McGraw-Hill, 1979).

Thanks to Steve Jarchow, CEO of Here Media and Regent Entertainment, for his many years of support of the WCFTR’s activities.

Kelley Conway, Tino Balio, and Lea Jacobs; Madison, WI September 2011.

I’ll never tell: JASON reborn

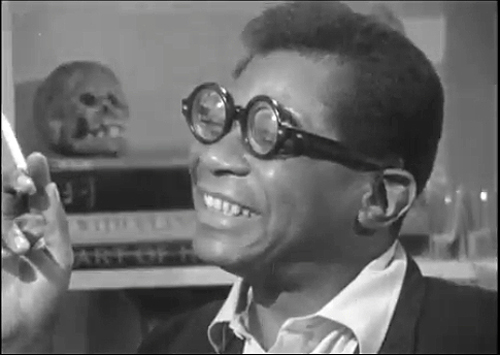

Portrait of Jason (1967).

DB here:

A white-walled apartment; no windows visible. Screen left: a day bed wedged into the corner. Center of screen: A fireplace and mantelpiece. Screen right: an easy chair with an end table boasting a lamp and ashtray. Behind it a bookcase. It’s as colorless a performance space as you could ask for, except perhaps for the skull on a bookshelf; but even that isn’t real.

In this arena a slender black man with thick Harold Lloyd glasses and a winning smile talks to us. His first words, delivered with calm sincerity, are immediately revealed as false.

My name is Jason Holliday. My name is Jason Holliday. (Breaks into laughter.)

(With a confiding smile) My name is Aaron Payne.

Over a single night, from 9 PM to 9 AM he talks to the camera, and eventually with the unseen filmmakers. High on marijuana and drunk on single malt scotch, he recounts his life as a gay hustler, recalls his family and childhood, and offers his analysis of how to behave around whites. He strikes attitudes, mimics the slaves in Gone with the Wind, and sings show tunes.

At first the filmmakers encourage him to tell this or that story, but late in the film one offscreen voice presses him. “Why’d you write letters about me?” “You should suffer.” “You’re full of shit.” Near the end Jason is sobbing. “If you don’t know,” he says, “I love you.” The offscreen voice is pitiless: “Stop that acting.”

Portrait of Jason (1967) is a legendary film that until recently had gone astray. Last Friday our Cinematheque hosted the US premiere of the restored version. The movie tells quite a story, but so too does Dennis Doros, VP of Milestone Films and the man whose tenacity brought back this delightful, disturbing record of Jason’s long night.

In and out of focus

It was a shocker in its day. What other film talked so frankly about gay life, race relations, and drug use? Where else would you hear virtually every four-letter word in the American vernacular? Shown in festivals and independent art houses, it won an astonishing level of praise. Here is Newsweek:

Jason lives, and Jason gives one of the most incredible performances ever recorded on film. This inverted Everyman, this anti-matter Jack Armstrong has a terrible tale to tell about how much it can hurt to be human, and he tells it in magnificently rich language with the gay desperation of an artist.

But the film was doubtless worrying. It circulated in the same year as Blow-Up, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Bike Boy, In Cold Blood, I am Curious (Yellow), Rush to Judgment, and I, a Woman—a year in which studio films, exploitation, art movies, and the underground seemed to be joyously blitzkrieging conventional values and good taste. Portrait of Jason opened at the New York Film Festival after a summer in which American cities had been shaken by riots in black neighborhoods. Now came a film in which a black man blithely reveals the cynicism behind his shuck-and-jive for rich white employers. And he’s a gay prostitute.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

Her other feature-length films (The Cool World, The Connection) owed something to American cinéma vérité. Variety sourly remarked of Jason, “C’est la vérité,” and ran its review alongside a review of Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies. But Clarke’s daughter Wendy recalls that although Shirley was friends with vérité filmmakers, she doubted that they could capture reality objectively. Leacock and Pennebaker would have found it impure to jab their own comments into the subject’s monologue the way Clarke and her lover Carl Lee do. Clarke’s approach is closer to that of the French cinéma direct, as pioneered by Jean Rouch and Chris Marker. In Le joli mai (1963) the filmmakers ask their interviewees frankly: “Are you happy?” This question underlies Portrait of Jason too.

Apart from the coaxing and goading interjections, Clarke’s filming method seems artless. There are fewer than fifty shots in 105 minutes, and they’re linked by black frames and out-of-focus passages. Both transitions mimic casual shooting. Yet Dennis Doros and Wendy Clarke pointed out that Clarke loved cutting. She was aware of the paradox:

I had enormous patience in terms of editing and I’ve always adored that part of making films, and in an odd way as I develop as a director I set up less and less situations to edit. The better I’ve become as a director, the less editing, the more I’m thinking in terms of the last twenty or thirty minutes that will have no editing at all.

In Jason the cutting isn’t as casual as it might seem. The blurry passages conceal edits, and the order of scenes doesn’t reflect the progress of the shoot. It will take patient research to determine the original chronological order of the reels we see. Clarke claimed that she enjoyed editing because at that phase she was really discovering her film.

Clarke’s apparently loose shooting, often running the camera until the magazine is empty, may seem a version of Warhol’s static films like Eat. It seems likely that she also learned from Warhol’s approach to performance. His psychodrama-based dramaturgy, as explained in J. J. Murphy’s fine book, constantly hovers between confession and put-on, and this is central to what happens in Clarke’s film. But Clarke gives her movie a more clear-cut narrative contour than Warhol would, with Jason’s monologue devolving from grinning self-assurance to stricken self-exposure.

Clarke and her crew acknowledge the act of filming, although they don’t emerge from behind the camera, as some do in The Connection. This recognition of artifice can encourage the subject to perform, to play up to the camera for the approval of the filmmakers and the audience. And a chance to perform is exactly what Jason wants. Now, he chortles, he can show off the nightclub act he’s been working on. The film is at once an audition and an effort to define himself. He’ll create “a picture I can save forever—one beautiful something that’s my own.”

So in the stage space between the day bed and the armchair, he strolls and poses. He fires off randy one-liners like “If I’d been a ranch, I’d be called Bar None.” Flipping his boa, he channels Mae West, Butterfly McQueen, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. (Did he rename himself in honor of Judy Holliday?) He jiggles ice cubes in his glass with the winking panache of Dean Martin at the Sands. Clarke once said that in watching the rushes she was reminded of her choreography films: Jason seemed to be dancing.

To recover from his numbers, Jason flings himself offstage, flopping back on the daybed or sinking into the armchair as his cigarette burns down to the filter. In these moments, he seems to be candid. He admits that even with all the money he’s borrowed from friends, he’s not ready to take the show-business plunge. Drunk and giggling, he tells of childhood beatings with a razor strop: you mustn’t stick your butt up high but press yourself against the bed; that hurts less. His oscillations of mood are dislocating, passing from exuberance to frankness to self-mockery. Moments of self-celebration (“I’m a male bitch”) can also seem inadvertent glimpses of vulnerability–which may be exactly what Jason wants us to think. At one level Jason gives lessons in impression management.

I see his tears at the climax as born of authentic pain, but I can’t be sure. Earlier in the film he bragged: “When I do my pathetic bag, I’m really pathetic.” The layers of Jason’s one-queen show seem endless. Clarke said in an interview that everything he does on film—his jokes, stories, even the weeping—she had seen many times before. “His entire life is a role.” He seems to spill everything, but one of his mottos, delivered with finger snaps, is: “I’ll never tell.”

Treasure hunt

Wendy Clarke, Dennis Doros, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey.

How was this extraordinary film brought to light again? That was the story Dennis Doros told at our departmental colloquium the day before the screening. His company Milestone has specialized in reviving forgotten or neglected films of all types, including American independent work like Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Simply trying to get a quality version of Portrait of Jason took him on a hunt that revealed, after many twists, that the closest thing to an original print was residing here in Madison, Wisconsin.

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research made an effort to collect off-Hollywood cinema, including the works of East Coasters like Emile de Antonio, Doris Chase, and Shirley Clarke. Clarke’s collection, like several others, harbors vast amounts of personal papers and film material.

Clarke shot Jason on 16mm, but no negative has yet been found. There were 35mm prints made, and some wound up in archives, notably at the Museum of Modern Art. But among the material Clarke began giving the Center in 1973 were six reels of silent 16mm footage and several reels of sound recording. When they were inspected, the reels were believed to be either outtakes or stretches of a rough cut. We didn’t yet have a release print of Jason to compare them to.

Many years later, after searching high and low across the world, Dennis had the good idea of adding up the footage counts of our reels. The length was four minutes longer than the final running time of the film. After further research, our footage was revealed as Clarke’s original cut of summer 1967, which was trimmed and revised for the film’s official premiere at the New York Film Festival. This was, says Dennis, “the great irony in the search. Because Shirley Clarke had created a film that was meant to look unedited—filled with out-of-focus shots and black leader—Shirley’s 16mm fine-grain master was hidden all these years as outtakes!”

Our archivist Maxine Fleckner Ducey assisted Dennis throughout his quest. They found that the sound material, alas, was indeed outtakes, and Dennis still needed a good 35mm print of the Film Festival/release version for sound and final checking. More hunting ensued. Searching through the WCFTR collection, Dennis found an old telegram from Jacques Ledoux of Belgium asking permission to borrow a print from the Swedish Film Institute. Dennis contacted Jon Wengstrom at that archive, and soon he had a copy that could guide the restoration.

The whole process was enabled by funding from the Academy and from a Kickstarter campaign. To support that effort, Dennis and his wife and business partner Amy Heller made a video that traces their search for Jason. Their restored version had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and it will go on to other festivals and selected theatres. The image and sound quality far surpasses that of earlier versions in circulation.

A sort of epilogue came when Dennis and Wendy Clarke visited Madison last week. They dipped into Shirley’s vast collection, and in only two days they found treasures of a personal as well as professional nature. Perhaps some of their discoveries will surface as bonus materials on the eventual DVD release. Dennis and Wendy stayed on to introduce Friday’s premiere and take questions.

A charming pendant to Jason was the screening of a half-hour of Wendy’s Love Tapes series. In the 1970s Shirley shifted to making videos, and Wendy followed her path and became a major video artist. The series began as Wendy’s video diaries, but in 1977 she began recording people talking about what love means to them. Each person sat alone in a room, seeing her or his image on the monitor, and talked for three minutes. Over the years, the formats shifted from reel-to-reel tape to VHS to DVD, but the theme remained the same.

Wendy now has over 2500 tapes, shot in museums, schools, shopping malls, prisons, centers for battered women, and even in a booth at the World Trade Center. Ideally, she says, everyone on the planet should make one—a goal that isn’t so far-fetched thanks to smart phones and the Internet.

The Love Tapes assembly we saw with Jason was broadcast on PBS in 1982, and it was alternately grave and exhilarating. People celebrated love they’ve found but also mourned its passing and reflected on how it shaped their lives. Wendy has tried other themes, notably death, but love works best. “You talk about everything in it.” Sort of what happens in Jason too.

Thanks to Wendy Clarke and Dennis Doros for their visit to Madison, and to Jim Healy for facilitating it. Thanks also to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski, two graduates of our program, for enabling the Academy to take part in Milestone’s project. Maxine Fleckner Ducey was a great help on the Milestone project and, on a daily basis, makes us proud to have the WCFTR connected to our program. Thanks as well to current WCFTR director Vance Kepley for background information on the Clarke collection.

Project Shirley recently won Milestone an award from the National Society of Film Critics (the company’s sixth). Look for more Project Shirley material to surface from our holdings. And who, as Dennis asked in colloquium, will write the first book on this remarkable artist?

I drew Clarke’s comments about editing from Gretchen Berg, “An Interview with Shirley Clarke,” Film Culture 44 (Spring 1967), 55; and “A Conversation—Shirley Clarke and Storm de Hirsch,” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967), 47. The Newsweek review of Jason appeared in the issue of 6 November 1967, and the Variety review appeared on 25 October 1967.

The trailer for the new version of Jason is here; it includes side-by-side comparison of an archived 35mm print and the restoration. Clarke’s discussion of Jason’s role-playing is captured in an episode of the TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe. You can watch it here.

On The Connection, see J. Hoberman’s lively introduction on the New York Review of Books blog. Jason is a prototype of the portrait genre of documentary, a subject covered with care in Paul Arthur’s essay, “Identity and/as Moving Image,” Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 24-44.

A sample of Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes is here.

Love Tapes (1982).

Sweet 16

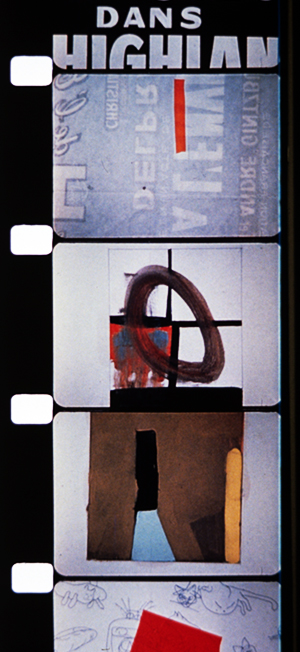

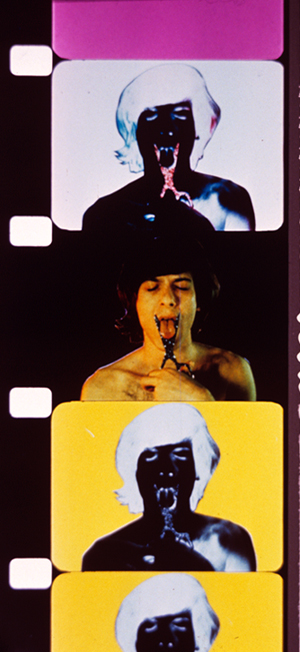

REcreation (Robert Breer, 1956); T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G (Paul Sharits, 1969).

DB here:

Snows and thaws and refreezing, amplified by a torrential rain, gave water a new path into our basement. We’ve spent about two weeks emptying bookshelves, drying them out, and shifting books to other places. No volumes were damaged, but we had to make space in the dry areas for the migrant titles.

That meant facing up to the problem of 16mm.

The solution was drastic.

Narrow-gauge movies

My film collecting started with 8mm. Not super-8; that was invented later. (Imagine how old I am.) I made my own movies in 8, but I also bought, from the venerable Blackhawk Films of Davenport, Iowa, copies of films in that format. Most memorable was the Odessa Steps reel from Battleship Potemkin, which I projected often on my bedroom wall.

Not until I went to college and joined a film club did I lay my hands on 16mm. I suppose if you start out handling 35mm, 16 looks skinny and 8 looks like a toy. But moving from 8 to 16, I could see only improvement. You could, with the sharp eyes of the teenage geek, actually see the image on the strip. I projected many films on our JAN surplus projectors, and one weekend I hauled a print of Citizen Kane to my apartment to watch several times. Do I need to add that all this was in the 1960s, long before films became available on videotape?

Arriving in Madison in 1973, Kristin and I bought a Kodak Pageant, the 16mm workhorse. Not as good as a Bell & Howell, most aficionados would tell you, but fairly cheap and easy to handle. When we moved from apartment to apartment, the Pageant went with us.

In 1977 we bought a house, and I set up a jerry-rigged projection room in the unfinished basement. In our second house, where we still live, I was able to set up something more permanent. Now there were two projectors encased in a booth and mounted on a platform.

We spent many hours watching movies in that currently soggy basement, with its burgundy carpet and dark wood paneling. Although the room lacked the comforts of what we think of as a home theatre, we sometimes screened things for big groups, either a party or once in a while students in a seminar.

In both venues, we previewed movies we were showing in courses and revisited some of our growing collection: The Shop Around the Corner, High and Low, True Stories (must blog about that some time), You Only Live Once, and so on. I’ve already expounded on the key role of His Girl Friday in our mini-cinémathèque.

By then Kristin and I had also started working with 35mm prints in archives and with 35mm trailers we scavenged to make slides for lectures. For a brief while we even had 35mm in our screening space, but with only one projector, shows stretched too long. Although home video had taken off, Betavision, VHS, and even laserdiscs couldn’t compare to a good 16 copy. We continued to collect and show on film, as did our department.

In the last decade, improvements in digital projection, along with the arrival of Blu-ray, led to the decline of 16 in our local media ecosystem. Our department still shows a lot of 35, but 16 seems mostly the province of our experimental and documentary courses. As for us, we hadn’t screened 16 at home for some years. Then came the February leak, and we had to face the problem.

We’d already given many of our 16mm titles to the department, keeping our most fond treasures at home, thinking we’d watch them some day. Now we needed the space that those cans and cases occupied. Anyhow, it was probably time to let go. So we decided to surrender the features, the shorts, the cartoons, the splicers and the rewinds and the six Pageants—everything.

Our house is a museum of defunct technology. Just recently I surrendered my lovely Teac reel-to-reel tape recorder. Packed away are hundreds of Beta and VHS tapes. On groaning shelves sit hundreds of laserdiscs, mostly Asian. Yet under a roof that houses no fewer than six laserdisc players, there is no trace of the predominant nontheatrical film format of the twentieth century.

FOOFs

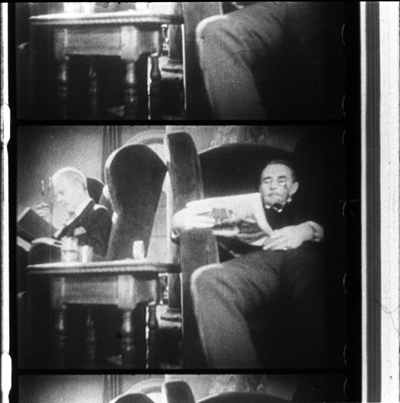

Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates (1966).

Nowadays it’s easy to own a “film”—or rather a disc or file or stream of pixels fed to your display. (Though I wonder what it means to “own” something sitting on the Cloud in your virtual locker.) Back in the day, joining the ranks of 16mm collectors meant a real commitment. You needed to buy gear, you needed to clean and inspect the films, and you needed to learn a little projector maintenance. You probably subscribed to The Big Reel and Classic Film Collector, tabloids that ran ads selling or swapping prints and equipment. And you usually went to film collectors’ conventions, jamborees of selling, trading, and movie watching. The three biggest events, Cinecon (Los Angeles), Cinefest (Syracuse), and Cinevent (Columbus, Ohio), brought together the overwhelmingly male tribe of FOOFs: Fans of Old Films.

FOOF collectors had good hunting in those days. There were plenty of 16mm prints floating around, but quality varied. The best were those cast off from legit distributors. Made from internegatives drawn from 35mm positives, they usually had good tonal values. At the other end of the scale were the dupes, copies pulled from 16mm distribution prints. These ranged from acceptable to awful; but if you wanted a rarity, you might have to spring for a dupe.

In the middle zone were TV prints, probably the majority of copies in circulation. When studios licensed their pre-1948 libraries to television, go-between companies like C & C put together packages of prints to be sold to local stations around America. Small stations in the hinterlands harbored scores of 16mm copies, to be trimmed, filled out with commercials, and broadcast outside prime time, and sometimes within it as “Million Dollar Movie” or whatever. It’s still not fully appreciated, I think, how many baby-boomer auteurists around the country caught classics in the pre-dawn hours on local television.

But as network and syndicated programming expanded, there was less room for old movies. Why run a 1936 Paramount picture when you could show color re-runs of Bewitched or The Six Million Dollar Man? The stations’ 16mm prints were headed for landfill when enterprising collectors and entrepreneurs salvaged them. You could tell when you got a TV print. It might carry a packager’s logo; it would have low contrast; and splices between scenes would signal where the commercials had been jammed in.

FOOFs had their demons and demigods. Principal among the demons was one colorful character, who had the habit of bothering collectors circulating versions of old classics to which he claimed current rights. In The Sneeze, FOOFs made fun of the man who, releasing recovered prints of Birth of a Nation and Keaton films, made sure his own name featured prominently in the credits.

Among the demigods were Kevin Brownlow, he who had rescued Napoleon, and David Shepard, who started out at Blackhawk and eventually founded Film Preservation Associates. Most legendary of collectors was William K. Everson, who died in 1996. Thousands of prints were squeezed into his two Manhattan apartments and spilled over into the storage areas of NYU’s film department. He acquired many of his films in exchange for services he rendered to Hollywood studios. His gems were screened in his courses, in sessions of the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, and in lectures he presented around the world. I remember his excellent presentation on Joseph H. Lewis at Chicago’s Art Institute Film Center, where he showed clips from Lewis’ Poverty Row productions and even some credit sequences Lewis had crafted.

Bill brought a magnificent selection of titles to Madison in the early 80s, and many of them, such as Bulldog Drummond (1929) and Justin de Marseille (1935), remain rarities. Generous beyond measure, he also let NYU faculty and students borrow his movies. When Annette Michelson needed to see East of Borneo (1931) for her essay on Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936), she turned to Bill. All of this largesse was made possible by the portable, user-friendly format of 16mm.

Freezing the frame

Teachers, filmmakers, and collectors had a special relation to 16mm. In addition, as researchers, we developed an unusually intimate rapport with the format. When I started teaching, I felt the need to illustrate my lectures with images from the films. My first efforts involved setting up a 35mm still camera on a tripod and photographing from the screen. If the projector could stop on a frame, so much the better; but even if not, you might snag an acceptable shot. The projected image would be surrounded by darkness. Today I wince at the results, as with this shot from Crime of M. Lange, one of the few old slides we haven’t cast out.

You could get sharper slides with a gadget called a Duplicon, but it cropped the 4 x 3 image to something like 3 x 2.

When Kristin and I decided to write Film Art: An Introduction, the few introductory textbooks relied almost entirely on production stills, those images shot on the set and circulated to promote the film. The Museum of Modern Art had an archive of production stills, and then as now, publishers turned to such collections for illustrations. As part of the first generation of university-trained film researchers, we doggedly insisted that all our examples would be actual film frames.

Today, digital video has made grabbing frames easy. But before the late 1990s, it was hard. Videotape frames looked terrible, as some books from the 1980s attest. To get decent quality, you needed access to prints. You needed a way to put a reel onto rewinds or, ideally, a flatbed editor like a Steenbeck. And you needed a camera with an enlarging attachment. When you’d copied your frames, you took the exposed film to a lab, where you hoped for a passable result. Black-and-white shots were easier than color, which required blinding lamps of a color temperature matched to Ektachrome or Fujichrome or Agfachrome.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

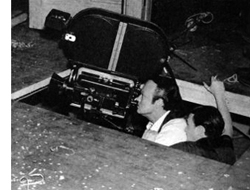

But most of the films we wanted to illustrate we could find only on 16. We rented prints and then took stills on a rickety gadget built for us by our friend David Allen. David bolted a pair of rewinds to a plank of plywood. That plank rested on a little table. Into the plank was cut a square slot for an upright light box. The box contained a bulb and was surmounted by a square of translucent plexiglass. The bulb could be put at the bottom of the box, for a photoflood lamp, or near the top with a cooler and dimmer appliance bulb for black-and-white. You positioned the film on the plexiglass and aimed the camera down at the film. A crude zoom lens allowed us to photograph a couple of frames of 16mm and one of 35.

We took the light box on our travels. Archivists certainly looked at us oddly when we brought the thing in, but they usually gave us permission to use it. We’d watch the film on a flatbed and bring the light box over alongside it. Laying the film gently on the surface, we’d poise the camera above it.

Here’s an example of what we got with our plywood setup, from Bill Everson’s print of Bulldog Drummond.

Over the years we improved our system. We bought better cameras, with sharper lenses. We found purpose-built attachments that hold the film strip firmly in place. (Alas, Canon and Nikon seem to have discontinued these rigs.) We used smaller lighting units rather than our curious box. For the last few decades we’ve shot horizontally rather than vertically.

Even in this age of video grabs, we make many frame enlargements on analog stock with 35mm cameras. Even if a film is available on DVD, some of the things we study aren’t preserved in that format. Of course many films aren’t available on video at all, and a great many of those were made to be seen on 16mm.

Format churn catches up with us

Notebook (Marie Menken, 1962).

Super-16 lives as a production format, but its older brother is nearly dead. True, a few die-hards like Ben Rivers continue to shoot on 16mm, but its future is mostly all used up. James Benning could make 16mm look like 35; when I asked him how he did it, he answered: “I use a light meter.” But even Jim has switched to digital. As for projection, many colleges and art centers have pitched out their 16 equipment.

Since our earliest editions, Film Art included discussions of two remarkable films: Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) and Robert Breer’s Fuji (1974). These have not been, and might never be, released on digital disc. Yet by the end of the 2000s, we found that virtually none of the users of our book screened these films for their classes, and curious readers without access to 16mm projection couldn’t easily see them. Reluctantly we cut them from the tenth edition of last year. We replaced A Movie with Koyanisqaatsi to illustrate associational form, and Fuji was replaced by Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue as an instance of experimental animation. Both titles are available on DVD.

Thanks to the Internet we’ve been able to revive our original discussions of the Conner and Breer films on our site here. We hope that will help the few loyal chevaliers who told me that they did indeed use the films in their courses. But our choice points up a larger problem.

So many documentary and avant-garde films were made and circulated on 16mm that we are at risk of losing a very large slice of film history. We’re lucky to have some Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton films on DVD, but what about all the other titles that were distributed by Canyon Cinema, the Film-Makers’ Coop, and other groups? We can get DVDs of Frederick Wiseman documentaries, and some classic ones have been made available on archival collections; but there are many more that depended on 16mm platforms. Even bigger is the set of everyday 16mm movies: amateur films, home movies, and hundreds of miles of newsfilm, from both big TV networks and local affiliates. A great many of the “orphan films” championed by Dan Streible and his colleagues are in this narrow-gauge format.

Recall too that the films of those animators and experimentalists who work frame by frame, such as Breer and Paul Sharits and Paolo Gioli, cannot be studied closely on DVD. How could DVD reveal to us the nifty paintwork of Marie Menken’s Notebook? For that you need a light table, or someone able to photograph it and show you.

Archives will retain 16mm projectors and viewing tables as long as they can. They will preserve prints, perhaps migrating the most sought-after ones to digital formats. Passionate collectors like Tim Romano, who zealously pursues lost films and then donates them to the AFI, will find a way to use our cast-off gear. Our Film Studies department will hang onto the format until the last aperture plate cracks.

16mm was so much a part of our work, our play, our education—in short, our lives—that the separation was inevitably poignant. Pinned to the bulletin board in my basement booth was Ellen Levy’s poem, “Rec Room.” It is, I think, about the fragility and faultiness of the 16mm image, as made palpable in home screenings, and about how that fragility nonetheless carries a pulse of vitality. It begins:

The film assumes the texture of its screen

on the first projection. Audrey Hepburn’s face

creases where the rec room paneling once

took exception to it for the sake of

rephrasing it slightly—a lesson

these late viewings have brought home. Home

screen or revival house . . . .

Thanks to Erik Gunneson and Tim Romano for helping us recycle our 16mm stuff.

Media historian Eric Hoyt, in our Communication Arts Department, studies among other things how the American studios disposed of their film libraries. He talks about his research and his book project, Hollywood Vault, here.

The FOOF contingent was unequivocally a force for good. To sample some of its wonkish hijinks, watch Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates.

New York University’s Cinema Studies Department has created an extensive online collection of William K. Everson materials. For more on Bulldog Drummond, see this entry and this essay on the great William Cameron Menzies. Annette Michelson’s essay on Joseph Cornell, “Rose Hobart and Monsier Phot: Early Films from Utopia Parkway,” was published in Artforum 11 (June 1973), 47-57.

Bonded Storage in Fort Lee is part of the history of American cinema, as this article shows.

Paradoxically, you can study films frame by original frame on some laserdiscs, and on VHS tapes too if you are aware of the 3:2 pulldown. See my entry here. As so often happens, progress along one dimension means regression on another. So I cling to my rotting laserdiscs and demagnetizing old tapes.

James Benning discusses how digital cinema changed his artistic practice at Bombsite. An earlier entry of ours showcases the efforts of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to preserve experimental cinema.

Ellen Levy’s fine “Rec Room” is available in its entirety in The New York Review of Books (9 October 1986).

To watch a video about our Film Studies program, go here.