Archive for the 'UW Film Studies' Category

Talks, pictures, and more

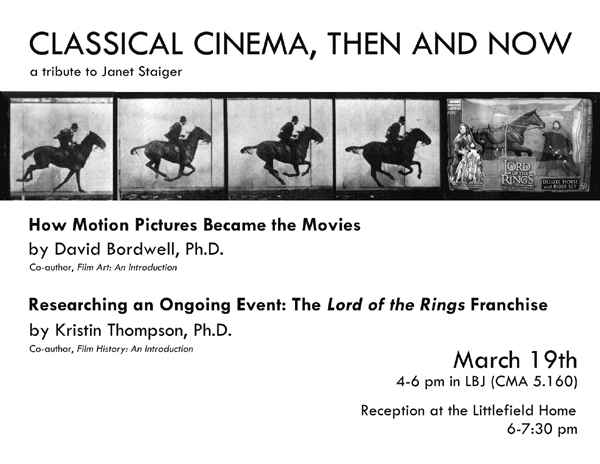

Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege, which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours, called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun (cont’d)

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course, “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen and the now-departed Capital City comics distribution firm. (DB)

Le mot Joost

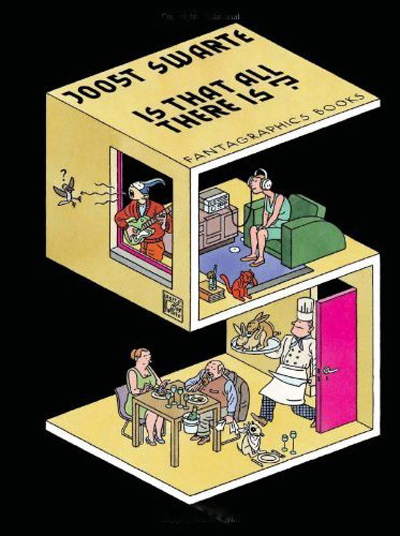

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here and here and here); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is?

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here and here, in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist, a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation.

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here.

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here.

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.

Dante’s cheerful purgatorio

Twilight Zone: The Movie.

DB here:

When will we baby boomers relax our chokehold on popular culture? Never, if the enthusiastic response to Joe Dante’s visit to Madison last weekend is any indication. A showing of Gremlins (1984) packed the house. A screening of his Twilight Zone: The Movie episode brought fans forward with DVD slipcases to sign. College kids reminisced about watching The ‘burbs with their dads and Explorers with their buddies (all on video, of course).

Although steeped in classical Hollywood, intimately acquainted with the most obscure output of the studios, Dante hasn’t abandoned the present. He shoots TV shows, webisodes, and the 3D feature The Hole (still awaiting a US release). He hosts a website, Trailers from Hell, in which directors comment on other directors’ works using a trailer as a point of departure.

His films, from Piranha (1978) and The Howling (1981) to the present, by way of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) and Matinee (1993), combine the gonzo spirit of the 1960s with a good-natured reverence for the past. Particularly movies. Particularly crazed, tasteless movies. Like Spielberg and Peter Jackson, he’s a fanboy. “Most filmmakers are kids at heart,” he says. “And all actors are.”

Unlike Spielberg and Jackson, though, Dante keeps politics close to the surface. His films sustain the baby-boomer hope that you can squeeze cultural critique into a genre project. Everybody knows that the Gremlins movies are subversive trips into the shadows of bourgeois normalcy. Has a shiny kitchen blender ever been used more efficiently?

The Gremlins pictures and The ‘burbs are valentines compared to Homecoming, Dante’s installment in the series Masters of Horror. This asks a simple question: Suppose that all the soldiers killed in combat were able to come back and vote? Is that a powerful lobbying group or what? When resurrected vets of Iraq start stalking to the polls, an Ann Coulter lookalike tries to stop them. Run on cable in 2005, this left-wing zombie movie slashes to ribbons pious platitudes about war’s costs. It’s required viewing for all 2012 presidential candidates.

Don’t crowd me, Joe

Dante began his career as a collagist. That’s not too fancy a name for a man who, with his friend Jon Davison, collected the ephemera of the great age of 16mm. TV shows, ads, and movie trailers swept out of local stations went into their archives. In time these and other glories of late-night TV found a new life, like a monster stitched together out of morgue remains. The strategy was simple. Dante and Davison rented five or six 16mm sub-B features and projected stretches of them, in rough order but jumbled together. The movies were interspersed with reels of clips.

The Movie Orgy played college campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Orgy lasted about seven hours, and its auteurs urged viewers to drift in and out. “Go get a pizza whenever you want. You won’t miss a thing.” Eventually Schlitz hired them to take it around the country and sold beer at the screenings.

When Dante began working for Roger Corman’s company—cutting trailers, thereby tapping his skills as a collage-maker—The Orgy was suspended. But some years ago the footage that he could find was transferred to digital and played at the New Beverly. It found a new success. Dennis Cozzallo has a lively tribute from 2008 here. Needless to say, we had to have The Orgy for Dante’s visit to Madison.

Affection for the detritus of the media takes many forms. After watching too many campus simpletons (both students and profs) laugh mockingly at Fritz Lang and John Woo movies, I’m opposed to condescension. I suspect Camp in its disdainful form. I don’t like people demonstrating their sense of superiority to the trash their parents and grandparents enjoyed. Knowingness leaves you with nothing.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

Moreover, in sequence after sequence, there’s a quality of astonishment that doesn’t make us feel superior. Take one exemplary moment of dépaysment. If you and I tried to be naive or trashy, we couldn’t come up with this.

Andy Devine hosted a kiddie TV show, Andy’s Gang, which featured Froggy the Gremlin (Plunk your magic twanger, Froggie!), the cat Midnight, and Squeeky the mouse (played by a hamster). About an hour into The Orgy, Andy induces Midnight to play a miniature pipe organ while Squeeky accompanies him. Cut to a deep-focus shot of what seems to be a slightly drugged cat locked in place and rhythmically pawing the offscreen keyboard. In the background Squeeky, apparently clamped within a mechanical mouse body, bangs a tiny bass drum. Andy sings along tunelessly. The song is “Jesus Loves Me.”

You don’t laugh, you gape. It’s like one of our local attractions, The House on the Rock: What’s disturbing is not that it’s done poorly, but that somebody thought of doing it at all.

The form of The Orgy—and it does have a form, of sorts—is to open with openings and end with endings. Several of the movies get started in the first half hour (Dante and Davison love opening credits) and we’re given enough of the plots to become curious. Most prominent are Attack of the 50-Foot Woman and Speed Crazy, the latter receiving a loving dissection highlighting, and repeating to the point of obsession the heel protagonist’s tagline, “Don’t crowd me, Joe.” Eventually the guy and his flashy sports car wind up crowded, all right–crowded into a ravine.

More TV episodes and movies get added as the hours roll by, and by the end we’re facing Armageddon. Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, New York, DC—every major city is under attack by some alien or giant monster. Sky King has to dump dynamite for some reason, Superman has to save Lois from a pistolero. A sort of amphetamine Intolerance, The Movie Orgy cuts together all these climaxes, which include The End titles that are far, far from signaling the end.

The clip from Andy’s Gang reminds us that the piece is somewhat misnamed. It’s a Movies And TV Orgy. More specifically, it’s a Movies On TV orgy. The structure of the whole shebang imitates a long stretch of television ca. 1955-1960. Over lunch Dante recalled watching Million Dollar Movie as a kid in New Jersey, seeing a feature shoehorned into a ninety-minute slot and chopped up by commercials. The Orgy replicates the jagged tempo of switching among three or four channels, glimpsing variant commercials for Colgate toothpaste or Raleigh cigarettes, catching a bit of this movie and then a bit of that one. With all its kid shows from my youth (The Lone Ranger, Lassie, Mighty Mouse, etc.) in endless eruption and interruption, it’s a baby-boomer time capsule. Puncturing this evocation of childhood are the clips scavenged from teenpix and Dick Clark’s dance show, Vietnam, Nixon’s Checkers speech, and film-society icons like the Marx Brothers, Fields, and Abbott and Costello. The late sixties counterculture breathes more fully in some clever fake ad spots. In one, a crucifix starts to wobble as the carved Jesus struggles to free his hands.

Dante claims that he and Davison were inspired to find out about the popular culture that shaped their parents’ generation. But nearly everything we see filled the airwaves during our younger days as well. The Movie Orgy in its current form seems to me a zestful celebration of the world our generation saw when we flopped on our bellies, propped our chins in our hands, and stared at the tumultuous world inside a black-and-white (not color) TV (not video) set (not monitor).

We cartoon characters can have a wonderful life

Dante the collagist leaves his fingerprints all over another film he screened here. When Spielberg launched his Amblin company, he hunted for directors who could make family entertainment in a genre format. Dante, who had already started Gremlins, was invited onto the omnibus Twilight Zone project. After the fatal accident on the Landis set, the studio backed off and it become “a movie they wanted to make but didn’t want anything to do with.” This gave Dante wide latitude and made him think, mistakenly, that studio suits always leave directors alone.

For this episode, Dante wanted to do an original story but Warners insisted that it had to be based on an episode of the TV series. He went back to the original Jerome Bixby story, which Dante and Richard Matheson reworked to add cartoons as a running gloss to the comic horror. The pseudo-family of demonic little Anthony inhabits a house that is half cartoonland, half-PoMo-Caligari. Saturated colors, occasionally striped with noir shadows, provide another Dante caricature of family domesticity, but now cartoons comment on the action. When Helen steels herself to eat, the dog on the screen behind her is doing the same.

The crisscrossed shadows of the corridors are replayed in the sawtooth walls pursuing Bimbo.

The collage principle gets developed further in Dante’s use of the soundtrack. The Movie Orgy uses no new sound work; the clips are just spliced together. But for the Twilight Zone episode, let loose in Warners’ classic archive, Dante could weave in Carl Stalling music (reorchestrated for stereo by Jerry Goldsmith) and a rich mélange of daffy sound effects.

The TV is incessantly on. The cartoons running in the background supply whizzes, boinks, and thuds that jarringly punctuate the conversation between puzzled teacher Helen Foley and the family that Anthony holds in his magical grip. “This is Helen,” says Anthony, introducing her to Uncle Walt and his sister, as we hear a smash from the TV set. The cartoon tracks comment on the action too. As the family settle down in front of the tube, the elders dote on Helen and we hear a Stalling rendition of “Ain’t She Sweet?” Dinner is served to the tune of “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic.” And when Helen discovers her burger has been slathered with peanut butter, the visceral image is underscored by warbling winds that rise when she lifts the bun. Eisenstein, for reasons given here, would have loved the moment. The whole sequence plays out as live-action animation, with naturalistic dialogue and effects given a creepy overlay by the cartoon track. Is Helen Foley’s last name part of the gag?

Dante, impresario of the comic grotesque, finds his inspiration in popular culture, the more wacko and inept the better. The comedy may come from childhood silliness, the grotesque from childhood fears. They say we baby boomers will always be just big kids, and Dante accepts this with a grin and a darkly cheerful eye.

Many thanks to the resourceful Jim Healy for arranging his friend Joe Dante’s trip to Madison. Thanks as well to the Cinematheque, the Marquee, and the Chazen Museum of Art for hosting the screenings.

John Carradine in The Movie Orgy.

Time for a quick one: A miscellany from friends

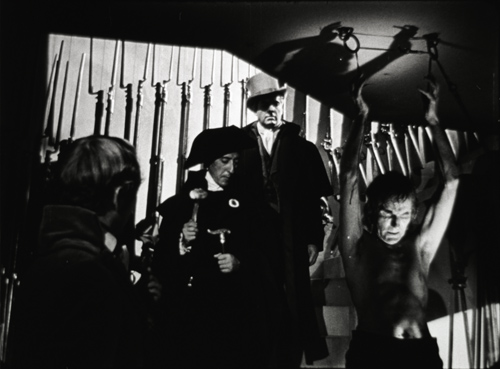

The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror).

DB here, catching up with books, videos, and events:

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

In The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror) Menzies found soul mates in two other aggressive pictorialists, Anthony Mann and John Alton, the team becoming “a crazy triangle,” eager to indulge in “thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositons.” Bob Cummings never looked so bizarre, before or since. I didn’t talk about this wild movie in my online Menzies material here and here because I had such poor illustrations from it. Now things have changed, and a decent, or perhaps rather indecent, sample of the film’s delirium (above) can serve to back David’s point.

David’s “Dreams of a Creative Begetter” is one of several film-related pieces in this issue of The Believer. The issue includes a DVD of the seminal People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), which gathered the talents of Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, and Rochus Gliese. A helpful introductory essay is at the Believer site.

Speaking of David’s writing, don’t miss his superb shot-by-shot analysis of a key scene in Gilda at his Shadowplay site, an obligatory stop for all cinephiles.

Seldom does a monograph on a single film probe so deeply as Mette Hjort’s new book on Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. It’s easy to take this movie as Dogme Lite, since compared to the earliest, rather harrowing Dogme efforts, it’s an ingratiating romantic comedy-drama. Mette does justice to this side of Scherfig’s film, but she also shows that it’s an exercise in moral seriousness. Reconstructing the production process, she conducts in-depth analysis of performance and technique. She is sensitive to actors’ moments, such as simply laying down a knife and fork; aware that these gestures are developed through improvisation, she is able to trace how each character is built up through details.

In her books and articles on the Dogme school Mette has shown that its innovations go beyond the vaunted technical “rules.” She always addresses them, of course; here she provides an illuminating typology of ways the rules have been followed or dodged. But she also stresses, as most writers don’t, that Dogme films engage with matters of political importance. For example, she has shown that The Idiots’ controversial display of “spazzing” triggered an important debate about Danish attitudes toward the disabled. In her new book Mette indicates that Scherfig’s efforts to endow her characters with the dignity to be found in everyday life offers viewers a chance “to re-connect with one of their culture’s most powerful moral commitments.” Mette talks about the project in this video.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

Michael starts by looking closely at the audiences and marketing. He suggests that viewers engage with the films through particular viewing habits (e.g., “Characters are emblems”). He then shows how these habits were nourished and refined by distributors, promotion, and film festivals. The next two sections of the book consider what we might take to be the two poles of indie difference from Hollywood: greater realism, and more self-conscious artifice. The central chapters analyze realism in relation to “character-centered” filmmaking in the Indie trend. Michael turns a critical eye on characterization in films as different as Walking and Talking, Lost in Translation, and Welcome to the Dollhouse. The third batch of chapters considers the trend’s other major appeal, the sort of play with style and form we get in the Coens, Tarantino, Nolan, and others.

Michael shows how character-driven realism and gamelike artifice mesh well with the mandates of distribution and reception—how, in effect, “originality” becomes something that can be calculated and branded. The book concludes with thoughts on the evolution of the trend, comparing Happiness with Juno and raising the inevitable question: How artistically independent is independent film? Newman leaves us pondering: “Indie cinema has become Hollywood’s most prominent alternative to itself.”

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

Chris concentrates on 1960s black-themed films from A Raisin in the Sun onward, because he wants to trace how filmmakers tried out a variety of ways to represent and comment on black life. It was a transitional era, but as he puts it “because of the insights they reveal about the periods that bracket them, transitional periods are among the most fascinating and significant in all of film history.”

For Chris, Gone Are the Days (1963), The Cool World (1964), Uptight (1968), The Landlord (1970), and the unproduced Confessions of Nat Turner provide case studies of alternatives to what became the crime-and-comedy product of blaxploitation. Why did decision-makers believe that black-themed films would sell broadly enough to repay investment? What choices and compromises were necessary to “universalize” material (for white viewers) while also retaining “authentic” blackness? Or was it better simply aim the films at white liberals?

Chris tackles such questions through a painstaking study of the film industry’s efforts to find, or create, an audience for films that took great risks. Written with verve (on the screen handling of the Black Panthers, Chris talks about Hollywood’s “Black Power outage”), Soul Searching revives films that are all but forgotten and shows how their efforts to create one variety of independent cinema failed for particular social and industrial reasons.

Someone I’ve been meaning to spotlight for a while: Frédéric Ambroisine is a multitalented critic, filmmaker, stuntman, and collector based in Paris. One of his careers is making supplements for French DVD releases of Hong Kong films, both classic and current. If you have even a smattering of French, you can follow his supplements with ease. He gets precious interviews with screen legends like Kara Hui Ying-hung and Ku Feng (below), master villain of the great New One-Armed Swordsman.

The videos from Wild Side often include Fred’s featurettes. You can follow Fred’s activities at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead. Much of the material in both places is in English.

Finally, if you’re in Los Angeles this week, why not visit the celebration of Orphan Films playing at UCLA 13 and 14 May? While I was in New York in February, I met NYU’s Dan Streible, moving spirit of the Orphan Films movement. Dan and his colleagues work with archives, collectors, and filmmakers to save films that fall through the cracks, digging up everything from home movies to news clips and experimental cinema. Dan curated a program of orphans at our local festival earlier this spring. At UCLA he will be a guest for screenings and discussions of many orphan titles, including the mysterious Madison Newsreel (Madison, Maine alas, not Wisconsin). Go here for Sean Savage’s discussion of the orphan oddity that has become a cult movie, and here for background on Northeast Historic Film, which found the footage.

PS: Speaking of friends, I should thank the solicitous people who wrote me during my recent illness. I appreciate your get-well notes, and I’m happy to report that I’m on the mend.

“World’s Youngest Acrobat” (Hearst Metrotone/ Fox Movietone 1929). From Orphans 7: A Film Symposium.

Rebooked

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, CinemaScope).

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers? I asked once before, but in a different tone of voice. Books are still being published, thick and fast, and everybody who cares about cinema should take a look at these.

In the frame

Ballet mécanique.

When the talk turns to the great film theorists of the heroic era, you hear a lot about Bazin and Eisenstein, less about Rudolf Arnheim. But the prodigiously learned Arnheim pioneered the study of art from the perspective of Gestalt psychology. Although he’s probably best known for his studies of painting in Art and Visual Perception, as a young man he was a film critic and in 1930 published a major theoretical book on cinema. First known in English as Film, then in its 1957 revision as Film as Art, this has long been considered a milestone. But Arnheim was famously skeptical of color and sound movies, and he had comparatively little to say about the many cinematic trends after 1930. (He died in 2007, aged 102.) While psychologists grew wary of Gestalt ideas, cinephiles embraced Bazin and academics moved toward semiotics and other large-scale theories. For some time Arnheim has seemed a graceful, erudite relic.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

This is no esoteric exercise. The essays present probing arguments with patient lucidity. Encouragingly, most of the contributors are early in their careers. (I have a piece in the collection as well, an expanded version of a blog entry.) The anthology proves that a seminal thinker can always be reappraised. There’s always more to be understood.

In the Higgins collection Malcolm Turvey furnishes an essay on Arnheim’s relation to various strands of modernism. That vast movement is treated at greater length in Turvey’s new book, The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s. At the book’s core are close analyses of five exemplary films encapsulating various trends. Turvey studies Richter’s Rhythm 21 and abstract film, Léger and Murphy’s Ballet mécanique and cinéma pur, Clair’s Paris Qui Dort and Dada, Dalí and Buñuel’s Chien Andalou and Surrealism, and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and the “city symphony” format. For each film Turvey provides informative historical background and, often, some controversial arguments. For example, he finds Léger to be surprisingly concerned with preserving classical standards of beauty. Indeed, one overall thrust of the book is to suggest that modernism was less a rejection of all that went before than a selective assimilation of valuable bits of tradition. (This applies as well to Eisenstein, I think, as I try to show in my book on his work.)

No less controversial is Turvey’s careful dissection of what has come to be known as “the modernity thesis.” This is the idea that urbanization, technological change, and other forces have fundamentally changed the way we perceive the world, perhaps even altered our basic sensory processes. Specifically, some argue, because the modern environment triggers a fragmentary, distracted experience, that experience is mimicked by certain types of film, or indeed by all films. Step by step Turvey argues that this is an implausible conclusion. This last chapter is sure to stir debate among the many scholars who argue for film’s essential tie to a modern mode of perception.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Cossar advances to more familiar ground, studying early widescreen practice in The Big Trail and moving to analyses of films by masters like Preminger, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin. Although most chroniclers of the tradition stop in the early 1960s, Cossar presses on to consider the changes wrought by split-screen films like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. The survey concludes with discussions of cropping techniques in digital animation (e.g., Pixar) and web videos, which often employ letterboxing as a compositional device. In all, Letterbox traces recurring technological problems and aesthetic solutions across a wide swath of film history.

Critics’ corner

Two of America’s senior film writers have revisited their earlier writings, with lively results. Dave Kehr’s collection When Movies Mattered samples his Chicago Reader period, from 1974 to 1986. Disguised as weekly reviews, Kehr’s pieces were nuanced essays on films both contemporary and classic.

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

It resurrects the flashback structure of his 1950 Sunset Boulevard, but it goes further, placing flashbacks with flashbacks and complicating the time scheme in a manner reminiscent of such demented 40s films noirs as Michael Curtiz’s Passage to Marseille and John Brahm’s The Locket. . . But the jumble of tenses also clarifies the film’s design as a subjective stream of consciousness. The images come floating up, appearing in the order of memory.

How many of those reviewers whose flash-fried opinions count for so much on Rotten Tomatoes can summon up information about the construction of Passage to Marseille or The Locket? And how many could make the case that Wilder, in returning to the forms fashionable in his early career, would repurpose them for the sake of a reflection on death, resulting in “a film as deeply flawed as it is deeply felt”? Kehr’s work from this period is appreciative criticism at its best, and he never lets his knowledge block his immediate response. “I admire Fedora, but it also frightens me.” It’s time we admitted that Dave Kehr, working far from both LA and Manhattan, was writing some of the most intellectually substantial film criticism we have ever had.

Also hailing from the Midwest is Joseph McBride, a professor, critic, and biographer. Apart from his rumination on Welles, his books have focused on popular, even populist, directors like Capra (The Catastrophe of Success), Ford (Searching for John Ford), and Spielberg (Steven Spielberg: A Biography). The University Press of Mississippi and bringing first two volumes of this trilogy back into print, and it has just reissued the third in an updated edition.

Here Spielberg emerges as far more than a purveyor of popcorn movies. McBride sees him as a restless, wide-ranging artist, and the additions to the original book have enhanced his case. McBride offers persuasive accounts of Amistad and A.I., which he regards as major achievements. He goes on to argue that Spielberg’s unique power in the industry allowed him to face up to central political issues of the 2000s.

He made a series of films in various genres reflecting and examining the traumatic effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the repression of civil liberties in the United States during the George W. Bush/ Dick Cheney regime. . . . No other major American artist confronted the key events of the first decade of the century with such sustained and ambitious treatment (450).

McBride is no cheerleader. He can be as severe on Spielberg’s conduct as on his films, criticizing much of the DreamWorks product as dross and suggesting that Spielberg sometimes trims his sails in interviews. I’d contend that McBride underrates some of Spielberg’s work, notably Catch Me If You Can and The War of the Worlds. But McBride has perfected his own brand of critical biography, blending personal information (he reads the films as autobiographical), tendencies within the film industry and the broader culture, and critical assessment. All studies of Spielberg’s work must start with McBride’s monumental book. Ten years from now we can look forward to another update; surely his subject will have made a few more movies by then.

Foreign accents

8 1/2.

Today we regard Citizen Kane as a classic, if not the classic. But for several years after its 1941 release it wasn’t considered that great. It missed a place on the Sight and Sound ten-best critics’ polls for 1952; not until 1962 did it earn a spot (though at the top). Its rise in esteem was due to changes in film culture and, some have speculated, the fact that Kane was a regular on TV during the 1960s. Something similar happened with His Girl Friday, another stealth classic. I’ve traced what I know about its entry into the canon in an earlier blog entry.

What about the postwar classics like Open City and Bicycle Thieves and the works of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni and Kurosawa and the New Wave? Surely some of the films’ fame comes from their intrinsic quality—many are remarkable movies—but would we regard them the same way if their reputation hadn’t spread so widely abroad, especially in America? Questions like this lead us to what film scholars have come to call canon formation: the ways artworks come to wide notice, receive critical acclaim, and eventually become taken for granted as classics.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 reveals a side of canon formation that’s too often overlooked. Balio is less concerned with analyzing films than Turvey, Cossar, Kehr, and McBride are. He is asking a business question: What led the U. S. film industry to accept and eventually embrace films so fundamentally different from the Hollywood product?

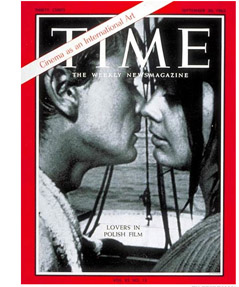

Several researchers have pointed to the roles played by influential critics, film festivals, and new periodicals like Film Comment and Film Culture. Intellectual and middlebrow magazines promoted the cosmopolitan appeal of the foreign imports. By 1963 Time could run a feverish cover story on “The Religion of Film” to coincide with the first New York Film Festival.

Balio duly notes the importance of such gatekeepers and agenda setters. But he goes back to the beginnings, with the small import market of the 1930s. Turning to the prime postwar phase, he broadens the cast of players to include the business people who risked buying, distributing, and publicizing movies that might seem hopelessly out of step with US audiences. He shows how small importers brought in Italian films at the end of the 1940s, and these attracted New York tastemakers, notably Times critic Bosley Crowther, who were keen on social realism. Within a few years ambitious entrepreneurs were marketing British comedies, Swedish psychodramas, Brigitte Bardot vehicles, and eventually the New Waves and Young Cinemas of the 1960s. As distributors fought censors and slipped films into East Side Manhattan venues, an audience came forward. The “foreign films”—often recut, sometimes dubbed, usually promoted for shock, sentiment, and sex—were positioned for the emerging tastes of young people in cities and college towns.

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Bryant Haliday and Cy Harvey of Janus Films. . . devised a successful campaign to craft an image of Bergman as auteur and to carefully control the timing of each release. . . . Janus released the films in an orderly fashion to prevent a glut on the market and to milk every last dollar out of the box office. No other auteur received such treatment.

The work paid off: Bergman made the cover of Time in 1960, and soon The Virgin Spring and Through a Glass Darkly won back-to-back Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. Eventually, Bergman and other foreign auteurs attracted the big studios. Now that small distributors had shown that there was money in coterie movies, the major companies (having problems of their own) embraced imported cinema—first through distribution and eventually through financing. If you admire Godard’s The Married Woman, Band of Outsiders, and Masculine Feminine you owe a debt to Columbia Pictures, which underwrote them.

Work like Balio’s does more than bring the name Cy Harvey into film history. It reminds us to follow the money. If we do, we’ll see that not every “foreign film” stands radically apart from big bad Hollywood. More generally, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens reminds us that even high-art cinema is produced, packaged, and circulated in an economic system. The distinction between commercial films and personal films, business versus art, is a wobbly one. Rembrandt painted on commission and Mozart was hired to write The Magic Flute. Sometimes good art is good business.

I couldn’t work this in anywhere else: The bulk of the essays in Arnheim for Film and Media Studies are by people associated with our department at Wisconsin. They do us proud, naturally. Incidentally, Joe McBride went to school at UW too, and Tino and I taught together here for over thirty years.

Dave Kehr maintains a blog and teeming forum here.

Hart Perez has made a documentary, Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. An excerpt is here. McBride’s website has information about his many projects.

James E. Cutting provides an unusually precise account of canon creation in his 2006 book Impressionism and Its Canon, available for free download here. I’ve written an earlier blog entry discussing Jim’s research into film.

My mention of American generations is based on Elwood Carlson’s study The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Carlson examines the varying experiences and life chances of people who fought in World War II; people who came of age during the 1960s; and the less populated cohort that fell in between. Doing some pop sociology, I’d hypothesize that the art-film market’s growth relied on a convergence of all three, which were more disposed to art film than cohorts in earlier periods. For example, veterans who had served overseas and gone to college on the GI Bill were more familiar with non-US cultures than their parents and, I surmise, weren’t entirely put off by foreign films. When I first met Kristin’s mother, Jean Thompson, she already knew the work of Carl Dreyer, having seen Day of Wrath at an art cinema in Iowa City. She was in graduate school after World War II, on the G.I. Bill, as was her new husband, Roger, also in school on the G.I. Bill and managing that art cinema. They saw Children of Paradise and other wartime foreign films just getting their releases in the U.S., as well as post-war films like Bicycle Thieves.

The Lucky Few, also known as the Good Times generation, were born between the late twenties and the early 1940s. They were well placed to enjoy postwar prosperity and the period’s explosion of artistic expression. The Lucky Few cohort includes powerful film critics like John Simon (born 1925), Andrew Sarris (1928), Richard Roud (1929), Eugene Archer (1931), Susan Sontag and Richard Schickel (1933), and Molly Haskell (1939). Aged between twenty and thirty when the foreign-film wave struck, they were mighty susceptible to it. (Pauline Kael, though born in 1919, had a delayed career start, entering film journalism in the 1950s along with Sarris et al.) You might slip in David Thomson (born 1941), Jonathan Rosenbaum (1943), and Richard Corliss (1944).

The Baby Boomers jumped on the carousel in the 1960s, with results that are all too apparent. Dave Kehr and Joe McBride are Boomers, as are Kristin and I. Tino, for the record, is ageless.

Minority Report.