Archive for the 'UW Film Studies' Category

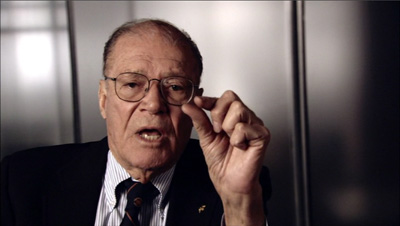

Errol Morris, boy detective

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara.

DB here:

Over a couple of sunny days in late October Errol Morris visited the University of Wisconsin—Madison. It was something of a homecoming. Morris took his BA in history here, and was inspired by two legendary teachers, Harvey Goldberg and George L. Mosse. (“The UW saved my life.”) After a few years in graduate schools (Princeton, Berkeley), he went into filmmaking, working with Werner Herzog on Stroszek while it was shooting in Wisconsin.

Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven (1978), examined pets, their owners, and the cemeteries that cater to both. Vernon, Florida (1981) reinforced Morris’s reputation as an aficionado of the backwoods bizarre. His reputation widened with The Thin Blue Line (1988), a true-crime story that cast doubt on whether an innocent man had been imprisoned for a murder. I’d argue that this film, along with Roger and Me, played a crucial role in opening theatrical markets to documentary film. From then on, Morris has been acclaimed as one of our finest filmmakers, finally receiving an Academy Award for The Fog of War (2003), a study of Robert McNamara’s prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven (1978), examined pets, their owners, and the cemeteries that cater to both. Vernon, Florida (1981) reinforced Morris’s reputation as an aficionado of the backwoods bizarre. His reputation widened with The Thin Blue Line (1988), a true-crime story that cast doubt on whether an innocent man had been imprisoned for a murder. I’d argue that this film, along with Roger and Me, played a crucial role in opening theatrical markets to documentary film. From then on, Morris has been acclaimed as one of our finest filmmakers, finally receiving an Academy Award for The Fog of War (2003), a study of Robert McNamara’s prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

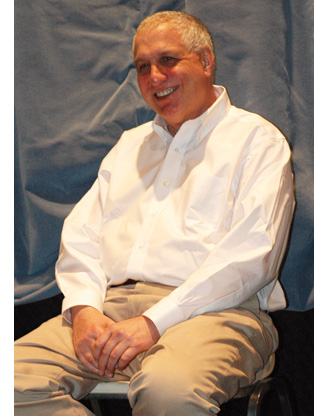

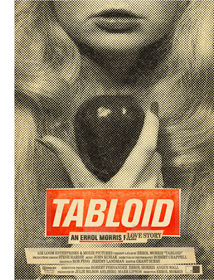

Morris’ visit was the culmination of months of screenings in several Madison venues. The big weekend was ushered in by a lecture by Carl Plantinga, one of our most distinguished scholars of documentary film. He’s a professor at Calvin College, and like Morris, he’s a Wisconsin graduate (my Ph. D. student, ahem). Dave Resha, who wrote a dissertation on Morris, and Bill Brown, our accomplished documentarist, were on hand to join our guest on a panel. Perky and boyish, Morris offered a public lecture at the Student Union. Next day, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art hosted a screening of his new movie Tabloid and a Q & A.

Morris is an exuberant presence, onstage and off. I could fill this entry with one-liners and anecdotes.

My high-school guidance counselor told me, “You should go to Wisconsin. They take anybody.”

I sometimes think of myself as someone who should be beaten up a lot.

Just because he’s a victim doesn’t mean he isn’t an asshole.

The electric chair is a very scary thing.

My wife says I should give up Twitter and start writing for fortune cookies.

Fred Leuchter, electric-chair repairman and Holocaust denier, smokes constantly but won’t be filmed with a cigarette. He explains, “You have to understand, Errol. I’m a role model for children.”

I don’t think anybody knows how crazy they are. I include myself and the persons in this room.

Morris’s visit was so stimulating that it got me thinking afresh about his career. While many documentaries engage in fact-finding, Morris’s films recall for me the figure of the classic detective, the nosy fellow drawn to secrets high and low. Morris is a fan of film noir (he thinks that Detour is at least as good as Citizen Kane) and he worked for a time as an investigator. His only fictional film, The Dark Wind (1991), is adapted from a Tony Hillerman mystery. It’s useful to think of Morris’s documentaries as private investigations—not illustrating an argument but exploring the mysteries around a situation or a personality. Like any investigation, his may lead nowhere or create more puzzles than it solves. Morris shines his penlight in some dark places, finding not only clues but some embarrassing items in the drawer or the back of the closet. The truth often has a sordid side, but that can harbor its own pleasures.

The filmmaker and the murderer

The Fog of War: “Rational individuals came that close to total destruction of their societies.”

History is a crime scene, and you’re the detective. Film can be a tool to solve the mystery.

Errol Morris

Morris’s recent films on the Vietnam War and on the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison (S. O. P.: Standard Operating Procedure, 2008) are somber inquiries into the mechanics of power and bureaucracy. Balzac said that behind every great fortune lies a great crime; for Morris behind every war lies many such crimes. Early on McNamara admits that his misjudgments cost thousands of lives. Morris’s reconstructions of prisoner treatment at Abu Ghraib are chilling neo-noir, filmed in chiaroscuro and featuring agonizing slowed-down imagery, as when a shotgun is fired into a cell and shells tumble out of the chamber.

He’s particularly interested in the photos snapped by the Abu Ghraib guards, and they provoked him to his lengthy New York Times blog essays on the philosophy of photography. S.O.P. and his writings ask how reliable a photograph is, how we can so easily miss what’s before us, and how what’s really happening–the chain of command, the war crimes that aren’t photographed, even another witness–can be hidden by the images we make. He often invokes a soldier’s remark about the Abu Ghraib pictures: “When you see a picture, you never see what’s outside the frame.”

The philosophical quests in Morris’s work lay at the center of Carl Plantinga’s presentation, “Errol Morris and the Anosognosic’s Guide to Documentary Film.” Carl trained as a philosopher, and his lecture teased out many concerns that weave through Morris’s work. On his website, Morris has written about anosognosia, the condition of not knowing that you don’t know something. It’s the realm of Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns.” Anosognosia, Morris claims, is “a universal condition of the human race.”

Carl’s talk developed this idea along several lines. Morris, he suggested, is a critical realist who believes that reliable knowledge is in principle attainable, even though we seldom attain it. Accordingly, Carl suggested, the films expose the mistaken beliefs of his subjects, their “epistemic distortions” revealed in behavior and, especially, language.

But the pathway to truth can’t be the cinéma-vérité methods of straightforward recording, if only because simply turning on the camera won’t give us access to the “mental landscapes” his speakers inhabit. For Carl, Morris deals in tragicomedy—sometimes bleak, sometimes absurdist, sometimes tinged with “fellow feeling.” His films can seem denunciatory, but they pause for moments of sympathy: a trial lawyer quits practice when justice is outrageously miscarried, the grunts at Abu Ghraib are scapegoated.

Carl invoked a controversy that has played out in academic circles but that Morris obviously feels passionate about. It centers on The Thin Blue Line. That film, some scholars argued, was a “postmodern” documentary. The conflicting testimony, rambling digressions, and incompatible replays seemed to display a corrosive skepticism about what really happened on the night that Officer Robert Wood was shot on a lonely Texas highway. Morris had apparently made a film about the impossibility of finding truth. Perhaps Morris encouraged that interpretation by remarks like this:

I like the irrelevant, the tangential, the sidebar excursion to nowhere that suddenly becomes revelatory. That’s what all my movies are about. That and the idea that we’re in a position of certainty, truth, infallible knowledge, when actually we’re just a bunch of apes running around.

Since then, though, Morris has been at pains to insist that The Thin Blue Line doesn’t say that arriving at a truth is impossible, only that it’s damnably difficult. Unlike the preformatted rhetorical documentary, a Morris film starts out from an uncertain place and moves into unknown territory. We may not arrive at certain truth or infallible knowledge, but that doesn’t mean that we’re forever floating in a realm in which belief in ghosts is as valid as belief in atoms. Randall Adams did not shoot Officer Wood, and David Harris probably did. Approximate but reliable truths are likely as close as we’ll get, and even those are very hard won. This is one reason Carl calls Morris a “critical realist”: There is a real world and there are true things to be said about it, but there are never any guarantees that we’ll find them.

Hence, again, the figure of the detective. The P. I. searches for the truth. The result may be partial, or vague, or so thickly wrapped in falsehood that it seems a pitiful thing. The trail is cluttered with distractions. With The Thin Blue Line, Morris developed a story line, starting with Randall Adams’ arrival in Dallas and ending with David Harris’s chillingly casual suggestion, captured on tape, that he was the guilty party.

The interviews provided the spine of Morris’s tale. But he embellished the interviews with inserts of documents (newspapers, police records), reenactments, and other images, some of them apparently irrelevant to the case: road maps, a drive-in’s popcorn machine, clips from Boston Blackie movies. In the terms we propose in Film Art, he gave his narrative form doses of associational form.

One function of this vagrant material is to remind us what any private dick knows: You have to sift through a lot of detritus to get to the important facts. (This idea seems literalized in the floating feathers and clumps of dust that irradiate the cell block in S. O. P.) Sometimes the detritus buries the facts, and you miss out. But some inquiries make progress. “It’s not just about constructing stories,” Morris says, “but finding things out.”

Morris’s films aren’t necessarily full records of an investigation but rather soundings and probes. The movies assemble, in provocative form, promising leads, false trails, and clues that are striking but still inscrutable. Sometimes what’s out of the frame is crucial. The viewer of The Thin Blue Line is likely to think that Harris’s climactic half-confession is what won Adams’ reprieve. In fact the decisive material was footage not in the final movie, drawn from interviews with Emily Miller and Michael Randell, along with proof that evidence was suppressed at Adams’ trial. As Morris is fond of saying, “What freed him was not the movie but the investigation.”

The lure of the lurid

Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control.

What amazed me was the number of murderers who’d come from Plainfield and the surrounding areas, so I started interviewing them, too . . . . At the time I remember my mother asking me why I didn’t spend time with people my own age. I said, “But mom, the murderers are my own age.”

Errol Morris

Emphasizing Morris’s search for truths may make him seem a more genteel filmmaker than he actually is. Another side of his work is an unabashed sensationalism. When I said to him, “You’re preoccupied with the weirdness of things,” he corrected me: “No, the profound weirdness of things.” The world is just plain strange (that’s part of what makes truth hard to get to) and it’s strange all the way down.

Morris has an appetite for free-range surrealism. Vernon, Florida began as an inquiry into a town whose citizens displayed a penchant for hacking off their arms and legs. (Pitching a fictional version, Morris proposed the one-sheet tagline: “If they would do this to themselves, think of what they would do to you.”) He has been intrigued by spontaneous human combustion, people struck by lightning, the search for Einstein’s brain, the breeding of giant chickens, and the efforts of a Minnesota man to build his own interstate highway.

At the limit stand figures preoccupied with end-of-life concerns—that is, the ending of other people’s lives. Morris’s time in Wisconsin with Herzog led him to Ed Gein, our state’s most famous grave-robber and the prototype for Norman Bates. Pretending to be psychiatrists, Morris and Herzog interviewed a serial murderer in California. Later, after working as a P. I., Morris heard of “Dr. Death,” a psychiatrist who specialized in testifying to the sanity of convicts on Death Row. A perfect subject for a movie, Morris thought, and checking into Dr. Death’s record he found Randall Adams’ case.

Morris’s cheerfully morbid curiosity, which puts him in the company of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, Ed Regis, and, of course, Herzog, is channeled into subjects that a high schooler might choose for a book report. Baby-boomer men, brought up on the Hardy Boys and Popular Science, are perpetual kids. Anything to do with magic, mystery, snooping, and weird science holds us fascinated. I’d bet that Morris has a set of William Poundstone’s wondrous Big Secrets books. How did he miss tackling UFOs?

So Morris is a connoisseur of weird science and lethal battiness. But it’s all in a day’s work for a P. I. The detective is inevitably drawn to seaminess, curiosities, and compulsions. Things that shock or disgust or baffle us can be clues to something we’d rather not face. In Morris’s hands, material that would shriek at us from supermarket racks can turn grotesquely comic (the early films), ominous (Thin Blue Line, Mr. Death), or strangely poetic (A Brief History of Time; Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control).

Come to think of it, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control would also be a good title for Tabloid. Joyce McKinney’s saga has enough spice for a full issue of Weekly World News: beauty contests, religious mania, kidnapping, bondage, flight from the law, cloned puppies, and Joan Collins. There are moments that demand blunderbuss typeface. I still want my Mormon! He was a doo-doo dipper! Booger gave me five black jellyrolls! And no reenactments now, just interviews enhanced by found footage, snapshots and headlines hurled into the frame. Once we’re dizzied from the bombardment of alluring phrases (Manacled Mormon Sex Slave!), we’re yanked into a circulation battle. The Mirror and the Express are deploying operatives to buy stories that will undercut each other.

Come to think of it, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control would also be a good title for Tabloid. Joyce McKinney’s saga has enough spice for a full issue of Weekly World News: beauty contests, religious mania, kidnapping, bondage, flight from the law, cloned puppies, and Joan Collins. There are moments that demand blunderbuss typeface. I still want my Mormon! He was a doo-doo dipper! Booger gave me five black jellyrolls! And no reenactments now, just interviews enhanced by found footage, snapshots and headlines hurled into the frame. Once we’re dizzied from the bombardment of alluring phrases (Manacled Mormon Sex Slave!), we’re yanked into a circulation battle. The Mirror and the Express are deploying operatives to buy stories that will undercut each other.

At some point we’re engulfed, and the tabloids become an alternative reality of magical transformations. An innocent girl, radiant in her own home movie, becomes a felon, and then her real transgressions come to light. The tabs’ endless escalation of sordidness, with each week’s scandal trumped by the next, gives the movie its pounding rhythm, the tempo of the rotary presses pumping out—what else?—stories that bury truth under trivia.

Except that this time around, the trivia are all we have, and the obsessiveness of the young McKinney is matched by that of the reporters pursuing her. Captured in pitiless high-definition, the men’s seamed faces glow with self-satisfaction and the thrill of the hunt. True, they’re investigators like Morris, and one journalist elicits some actual conversation with our offscreen filmmaker. (They discuss the phrase “barking mad,” which Morris wishes Americans used more often.) After a while, though, we can add these Grub Streeters to Morris’s gallery of people who talk and talk without any sense of what they’re giving away.

The great mystery

The Thin Blue Line.

Even as [the writer] is worriedly striving to keep the subject talking, the subject is worriedly striving to keep the writer listening. The subject is Scheherazade. He lives in fear of being found uninteresting, and many of the strange things that subjects say to writers—things of almost suicidal rashness—they say out of their desperate need to keep the writer’s attention riveted.

Janet Malcolm

The detective, by vocation, asks questions. A detective-story plot consists largely of following the investigator pounding the path, interrogating witnesses, suspects, and experts. (With time out for occasional pistol ambushes, seductions, and whacks on the back of the head.) What people say and how they say it can lead you to truth, or to the profound weirdness that informs the human condition, or both.

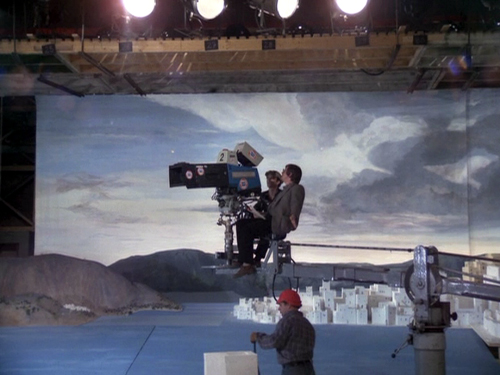

Hence the very special conditions for a Morris interview. Complex lighting, and in the later films artificial backdrops, create the aura of a special occasion. Hair and make-up are attended to. Up to twenty crew members are at work. Looming in front is the Interrotron, that mad-scientist rig of mirrors that lets the interviewee look at Morris while also looking into the camera. In a later development, several cameras are trained on the speaker. In all, it’s not quite like being dragged to sit in the hot seat at Headquarters, but there is an almost ceremonial surrender of autonomy. All the subject can do is talk, and aim it directly at us.

Morris does not provide questions in advance. He starts by saying, “I don’t know where to start.” He doesn’t pounce on his subjects (he calls them his “characters”). He speaks as little as possible, regarding it as best to let the people gabble on. Thanks to videotape, they can talk uninterrupted for hours. We seldom hear his questions. He never comes on camera to make himself the protagonist or star (à la Moore), nor does he provide a stream of voice-over narration (à la Curtis). We have simply to look at these people and listen to what they say.

During his stay in Madison, Morris referred often to the case of Scott MacDonald, the convicted murderer whose case journalist Joe McGinnis turned into a bestseller. Of particular interest to Morris was Janet Malcolm’s book about the case, The Journalist and the Murderer. MacDonald sued McGinnis for seeming to support his case during the trial, then publishing a damning account declaring MacDonald guilty as charged. Analyzing MacDonald’s litigation, Malcolm reflects on the betrayal at the heart of journalistic inquiry. The subject interviewed wants the story told his or her way; the writer, at least the writer of conscience, can never fulfill that pledge. The naivete of the subject is always shattered when the story is published, for the writer had another agenda.

Malcolm’s book intersects Morris’s concerns at several points: a tabloid murder, a man perhaps wrongly convicted, a subject sueing the writer (as Randall Adams eventually sued Morris). In particular, I think that Morris is taken with the idea that interviewees have a kind of compulsion to keep talking. They want to explain themselves fully, of course, and to justify what they’ve done. But they also want to prove themselves worthy of someone else’s interest. Compulsive confessors, they want to be caught and are always startled when they are.

Morris’s ultimate interest, Carl Plantinga noted, lies in people’s “mindscapes,” their private construals of reality. Morris seemed to agree. The great mystery, he said, is “human personality, who we are.” That includes all the madness and dirt. The surprises that pop out, Interrotron or no Interrotron, remind us that we’ll never completely crack the case.

For much more on Morris, visit his website. He tweets here. His New York Times essays on photography are now evidently behind a paywall, but an all-out search will reveal some of them. Here is a pdf of what I think is the first one. A more recent cycle starts here. A book of Morris essays is planned for publication.

The best compendium of Morris’s evolving ideas is Livia Bloom’s collection Errol Morris Interviews (University of Mississippi Press, 2010). From this book, I’ve quoted Morris’s remarks in Chris Chang’s 1997 Film Comment article “Planet of the Apes,” p. 56, and in Paul Cronin’s wide-ranging “It Could All Be Wrong: An Unfinished Interview with Errol Morris,” p. 165. My quotation from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer is from pp. 19-20.

Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film has recently come back into print, and I discuss it briefly in a recent entry.

I wrote an analysis of The Thin Blue Line in Film Art, ninth edition, pp. 425-431. We contrast Morris with Michael Moore and other documentarists in Film History: An Introduction, third edition, pp. 544-548.

The Wisconsin symposium, Elusive Truths: The Cinema of Errol Morris, was a model of campus cooperation. Thanks to the Wisconsin Union, and especially the dedicated students of the WUD Distinguished Lecture Series, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, our Cinematheque, the University of Wisconsin Foundation, the UW Arts Institute, and other agencies, not least my home Department of Communication Arts. We owe a special debt to Professor Vance Kepley who orchestrated the event with aplomb. A full record of events, sponsoring bodies, and people to be grateful to can be found here.

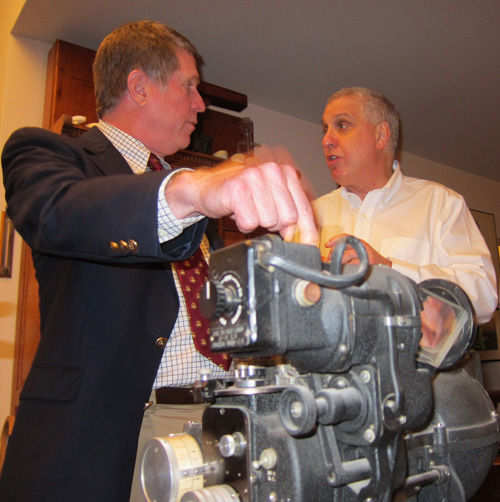

Vance Kepley and Errol Morris discuss the once-top-secret Norden bombsight.

Take it from a boomer: TV will break your heart

DB here:

Every so often someone will ask Kristin and me: “Why don’t you write about television?” This is usually followed by something like:

”You’re interested in narrative. The most exciting narrative experiments are going on in TV, not film.”

”You’re interested in visual experimentation. The most exciting developments in visuals are in TV.”

”TV is where the audience is.” Or “TV is where the culture is.”

”Film is borrowing a lot from TV, and producers and directors are crossing over.”

We might answer by saying we don’t watch any TV, but that would be a fib. Like everybody, we watch some TV. For us, it’s cable news commentary, The Simpsons, and Turner Classic Movies.

Truth be told, we have caught up with some programs on DVD. We watched the British and the US versions of The Office and enjoyed both (though the American version, no surprise, makes the characters more lovable). Kristin watched The Sopranos’ first season for a particular project. For similar purposes I watched and enjoyed Moonlighting and some Michael Mann TV material. Intrigued by the formal premise of 24, I dipped into the first season, but I found it visually so wretched I couldn’t continue. I got through four seasons of The Wire on DVD, largely because of the Pelecanos connection, but I found it over-hyped. It seemed to me a sturdy policeman’s-lot procedural, but rather fragmented and uninspiringly shot.

That’s it for the last three decades. No real-time monitoring of episodic TV (we haven’t seen Lost or Mad Men or the latest HBO sensations) and none of the reality shows or the music shows or even comedy like Colbert or Jon Stewart.

So we aren’t plugged in to the TV flow. Americans currently log over four and a half hours a day in front of the tube, so clearly we’re derelict in our duty. As Clay Shirky points out in Cognitive Surplus, TV viewing is Americans’ unpaid second job.

But why don’t I start following episodic TV? The answer is simple. I’ve been there. I was a TV kid before I was a film wonk. And I can assure you that watching TV leads to painful places—frustration, anger, sorrow. All you’re left with is nostalgia.

Commitment problems

I see the difference between films and TV shows this way. A movie demands little of you, a TV series demands a lot. Film asks only for casual interest, TV demands commitment. To follow a show week after week, even on a DVR, is to invest a large part of your life. Going to a movie demands three or four hours (travel time included).

Whether a movie is good or bad, at least it’s over pretty soon. If a TV show hooks you, prepare for many long-term ups and downs—weak episodes, strong ones, mediocre ones. Favorite actors leave or die, and replacements are seldom as good as the originals. A new character may be charming or annoying. An intriguing hero may accumulate distracting sidekicks. Plots take weird turns, sometimes dillydallying for months. All this can drag on for years.

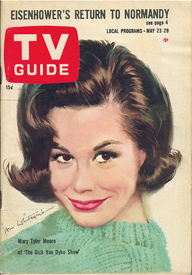

Of course TV-philes enjoy this slow samba. They point out, rightly, that living through the years along with the characters, watching them change in something like real time, brings them closer to us. Who doesn’t appreciate the way Mary Tyler Moore evolved into something like a feminist before America’s eyes? As early as 1952, the sagacious media critic Gilbert Seldes pointed out that intellectuals who thought that TV was plot-dependent were wrong.

It is natural that the actual plot of a single self-contained episode should be comparatively unimportant. . . . The very limitations of the style leads its creators to develop characters of considerable depth, to create dramatic conflict out of the interaction of people rather than out of an artificial juxtaposition of events. As television is a prime medium for transmitting character, this is all to the good (Writing for Television, pp. 115-116)

We get to know TV characters with an informal intimacy that is quite different from the way we relate to the somewhat outsize personalities that fill the movie screen. We learn TV characters’ pasts, their hobbies, their relations with kin, and all the other things that movies strip away unless they’re related to the plot’s through-line.

Having been lured by intriguing people more or less like us, you keep watching. Once you’re committed, however, there is trouble on the horizon. There are two possible outcomes. The series keeps up its quality and maintains your loyalty and offers you years of enjoyment. Then it is canceled. This is outrageous. You have lost some friends. Alternatively, the series declines in quality, and this makes you unhappy. You may drift away. Either way, your devotion has been spit upon.

It’s true that there is a third possibility. You might die before the series ends. How comforting is that?

With film you’re in and you’re out and you go on with your life. TV is like a long relationship that ends abruptly or wistfully. One way or another, TV will break your heart.

TV brat

Trust me, I’ve been there. Unlike most film nerds, I wasn’t a heavy moviegoer as a child. Living on a farm, I could get to movies only rarely. But my parents bought a TV quite early. So I grew up, if that’s the right phrase, on the box.

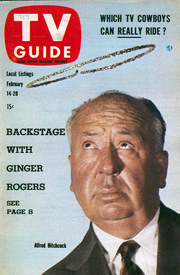

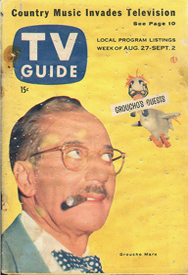

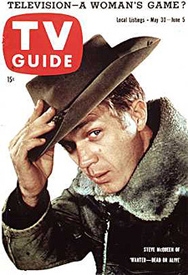

Childhood was spent with Howdy Doody (1947-1960) and Captain Video (1949-1955) and Your Hit Parade (1950-1959) and Jack Benny (1950-1965) and Burns and Allen (1950-1958) and Groucho (You Bet Your Life, 1950-1961) and Dragnet (1951-1959) and Disneyland (1954-2008) and The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1959). With adolescence came Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965) and Maverick (1957-1962) and Ernie Kovacs (in syndication) and Naked City (1958-1963) and Hennesey (1959-1962) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) and Route 66 (1960-1964) and The Defenders (1961-1965) and East Side, West Side (1963-1964).

Some of the last few titles I’ve mentioned evoke particularly fond feelings in me. At a crucial phase of my life, they presented models of what the adult world might be.

For one thing, adults had an easy eloquence. Some of these shows seem overwritten by today’s standards, but actually they brought to television a sensitivity to language that seems rare in popular media now. Bret Maverick had a smooth line of patter, and even racketeers on Naked City could find the words. Dragnet‘s dialogue is remembered as absurdly laconic, but actually it showed that very short speeches could carry a thrill. At the other extreme were the soliloquys in Route 66. One that sticks in my mind came from a daughter, torn between love and exasperation, saying how touched she was when her father called one of her simpleton boyfriends “uncomplicated.” (The line was modeled on something said by Faulkner, I think.) I don’t recall characters insulting one another as much as they do nowadays, and of course obscenity and body humor were yet to come. At that point, TV relied so much on language that it might be considered illustrated radio.

Second, these shows made heroes of adults who were reflective and idealistic. They mused on social problems and thought their positions through. The father-son lawyers of The Defenders often disagreed about the moral choices their clients had made, and as a result you saw the different ways in which legal cases shaped people’s lives and public policy. Even a cop show like Naked City was less about fights and chases than it was about the causes, and costs, of crime.

Third, adults were empathic. This was partly, I suppose, because I was drawn to liberal TV; but I think it’s striking that my favorite dramatic shows showed professionals committed not to billable hours but to helping other people.

El segundo pueblo

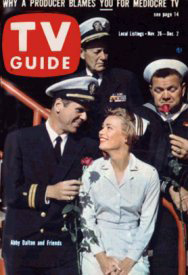

These qualities were epitomized in Hennesey. The continuing cast was small. Chick Hennesey (Jackie Cooper) is a navy doctor in his mid-thirties. His irascible superior Captain Shafer, is played by Roscoe Karns, bringer of dirty fun in 1930s and 1940s movies (“Shapely’s my name, shapely’s my game”). Nurse Martha Hale (Abby Dalton) serves as a romantic interest for Hennesey, and Max Bronski (Henry Kulky) is a dispensary assistant; both are vivid characters in their own right. A few others pop in occasionally, notably the rich eccentric dentist Harvey Spencer Blair III (played with eerie passivity by James Komack).

The series began as a situation comedy, but soon it became an early instance of the “dramedy”—the TV equivalent of sentimental comedy. In this classic genre, moderately grave problems cannot shake the essential concord of human relations. The tonal mixture makes a laugh track distracting; Hennesey‘s was eventually phased out.

The series was created and largely written by Don McGuire, who modeled his protagonist on a doctor he admired. Hennesey is l’homme moyen sensual, a man of no great ambitions or grand passions. He smokes cigarettes (Kent was a sponsor) but, surprisingly, doesn’t drink alcohol. He served in the army when very young (at Guadalcanal), went to UCLA medical school, and was drafted into the navy. Neither a career officer nor an ordinary doctor, he is more at home with enlisted men than the brass.

Hennesey isn’t a dramatic blank, but his virtues are quiet ones. He simply wants to help people get over the daily bumps in the road. He stammers when bullied by someone more aggressive, but sooner or later he quietly stands his ground. When he has a chance to do something decisive, he does it without fanfare. In the pilot episode, he has to override Shafer in order to extricate a man’s arm from a flywheel. But afterward he is likely to wonder whether he did the right thing. He often confesses his fears and weaknesses. Hennesey is a prototype, far in advance, of the caring, sharing male. He is, as Martha sometimes tells him, nice; but that sounds too soft. He is simply decent.

The plot often calls on him to confront people far more harsh and self-centered than he is. Often Captain Shafer, playing the narrative role of Arbitrary Lawgiver, assigns Henessey to unpleasant duties, like dealing with a lady psychologist who wants to find out why men join the navy. Often Henessey has to help men and women adjust to navy life, or to tell them that they are too unhealthy to continue. Sometimes he reminds arrogant doctors why they took up the calling. He also encounters civilians with problems that impinge on his own life. Going home to meet the doctor who inspired his career choice, he finds a bitter widower. In other episodes he simply observes someone else rising to the occasion. A bumbling helicopter pilot is a figure of fun until, behind the scenes, he risks his life to save a girl with appendicitis.

Everything about the series is modest: the level of the performances (only Shafer raises his voice), the accidents and digressions that deflect the plot, the cheap sets and recycled exterior shots, the jaunty hornpipe score that becomes an earworm on first hearing. But all these things enhance that TV-specific sense of a comfortable world with its familiar routines and unspoken bonds of teasing affection.

The show illustrates one of the virtues of TV of the time: talk. Characters emit single lines or even single words at a pace recalling that of the 1930s screwball comedies. Nurse Hale is the fastest, Shafer comes next, and Hennesey is left to play catch-up. In one episode, Shafer has just learned he’s going to be a grandfather, and he leaves the office euphoric. But Martha is a beat ahead.

Hennesey: I betcha this has him in a good mood for weeks.

Martha: For what?

Hennesey: For days.

Martha: Do you want to bet that within thirty seconds he’ll be in a bad mood?

Hennesey: No, that’s ridiculous.

Martha: Is it?

Hennesey: Of course. What could possibly get him upset in—?

Shafer returns, frowning.

Shafer: I just thought of something.

Martha: His first grandchild will be born overseas.

Shafer: Right.

Martha (to Chick): Think you’re playing with kids, huh?

The exchange, including blocking, takes nineteen seconds. It’s conventional, I suppose, but its brisk conviction modeled for one thirteen-year-old the possibility that adults are alert to each moment and enjoy rapid-fire sparring with their friends.

Harvey Spencer Blair III has more highfalutin rhetoric. In a 1961 episode, he declares his plan to run for mayor of San Diego.

Harvey: My election will see the rise of little people to positions of consequence, the molding of our future cultures, the era of a new world. Join with me, my dear, in crossing the New Frontier.

Martha: Leave the petition with me, Dr. Kennedy.

Harvey: I revel in the comparison.

Here even the double takes are modest. Characters react with a frown or a tilted chin or a widening of the eyes or a slight shake of the head. There can be verbal double-takes as well, mixed in with overlapping lines in the His Girl Friday/ Moonlighting manner. At the start of a 1961 episode, Martha enters the infirmary. Henessey is at the desk and Max is filing folders.

Without looking up, Chick says what he thinks Nurse Hale should say.

Hennesey: Morning, Max. Morning, doctor. Sorry I’m late.

Martha: I am not.

Hennesey (looking up): You’re not? It’s ten minutes after eight–

Martha (overlapping): I mean I’m not sorry. I have a very good excuse.

Hennesey: You had a run in your mascara?

Martha: I had to stop and talk to the senior nurse.

Max: Did you get it?

Martha: Yes.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: Good, I’m glad.

Martha: Thank you, Max.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: I bet it’ll be nice up there.

Martha: I hope so—

Hennesey (overlapping): Up where?

Max: If it isn’t too cold.

Hennesey: Oh, no, it can’t be too cold, it’s only cold up there in August—that is, if the winds from the equator don’t –Look, you two, don’t you think it’s only fair that if you discuss something in front of a third party, you might just—

Martha: A run in my mascara?

Nobody I knew talked like this, but why not talk like this? It would make life more lively. Backchat, I’ve learned over the years, can get you in trouble; life isn’t a TV show. But I still think that repartee, especially featuring stichomythia, is one of the pleasures of being a grownup. So too are the catchphrases we weave into our chitchat. The Hennesey tag I enjoyed was “El segundo pueblo,” uttered oracularly at a moment of crisis, and always translated with a different, incorrect meaning. My own life would feature motifs like “A meatloaf as big as the Ritz” (undergrad days), “Kitchen hot enough for you yet?” (grad school), and “If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it” (professorial years).

Being a film wonk, I can’t rewatch episodes without noting that those directed by McGuire have some flair. His staging fits the characters’ unassuming demeanor, providing a deft simplicity we don’t find in modern movies. This is doorknob cinema; scenes start when somebody enters a room. And people in the foreground respond to others coming in behind them.

The faster the gab, the slower the cutting, but extended takes can refresh the image by moving actors around. In one scene, Harvey, still planning to run for mayor, is slated for a court-martial. He enters to get the news. His somewhat zombified gait contrasts with Hennesey’s peppy, arm-swinging stride, usually on exhibit during the opening credits. (I learned things about grown-up walking styles too.)

As the shot goes on, Harvey gets the news he’s headed for the brig. Shafer and Hennesey gloat, but in the foreground, Martha suspects that Harvey’s got an ace up his sleeve.

When Harvey says he can’t attend his hearing, Martha lifts her cup: “Here comes the voodoo.”

Harvey reminds his colleagues that he’s due to be discharged from the service before the hearing date. The ensemble responds by regrouping, with Martha and Shafer trading places in the foreground and Hennesey slinking off.

When everybody has assumed a new position, Harvey volunteers to re-up, causing Shafer to shudder.

As Martha sits and Hennesey comes forward, Harvey produces some tickets for his campaign rally, at which Clifton Webb (yes, go figure) will be speaking. Interestingly, Jackie Cooper stays a bit out of sight, preparing for a later stage of the shot.

Harvey leaves, and Shafer’s attention turns to Hennesey as the person to be blamed.

Soon we are seeing characters moving in depth again as Martha gives a typical head-shake in the foreground.

The shot exploits principles of 1940s Hollywood depth staging, as did many of the filmed programs of the period. (The Defenders is particularly rich in this regard.) Simple and sharp, McGuire’s scene is more skilful than anything I saw yesterday in The Expendables.

Chick and Martha got married in the last episode of the series, in May of 1962. I would never see these people again, except in re-runs and syndication. In fact, all my favorite programs were cancelled during my high-school years. I set out for college in summer 1965, disabused of my love for TV. Ahead lay cinema, which would never betray me.

Of course watching a TV series on DVD changes the dynamic of week-in, week-out absorption; but the rhythm of real-time viewing seems to me one of TV’s artistic resources. Besides, wading through a whole series on DVD is still a hell of a commitment.

Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television is an original and imaginative study of conventions that still hold sway. He’s especially astute on how the differences in conditions of reception (film, public; TV, domestic) shape creative choices. Another entry on this site discusses Seldes as a critic of modern media.

On the idea that we are especially susceptible to popular culture in our early teens, see our earlier entry here.

Extensive collections of some of my favorite shows, like Reginald Rose’s The Defenders and David Susskind’s East Side, West Side are available for study in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Nat Hiken, a Milwaukee boy, also generously left us a cache of Bilkos and Car 54s.

Hennesey, once rerun on cable channels, has evidently never been published on DVD. Gray-market discs offer a few fugitive episodes, recycled from VHS, kept alive by others with an affection for the program. The most complete information I’ve found on the series is in David C. Tucker’s Lost Laughs of ’50s and ’60s Television: Thirty Sitcoms that Faded Off the Screen (McFarland, 2010), pp. 47-53. A list of episodes and broadcast dates is here.

For more on one staging technique that McGuire uses, you can visit our post on The Cross. See also Jim Emerson’s outstanding analysis of composition and cutting in Mad Men at scanners; the sequence he studies is reminiscent of mine. The best guide to analyzing TV technique is Jeremy Butler’s landmark Television Style.

George C. Scott in East Side, West Side. Stephen Bowie’s Classic TV History site provides a detailed study of this series.

PS 10 September 2010: Believe it or not, I hadn’t read A. O. Scott’s praise of current TV before I wrote this, but his thoughts develop the sort of ideas I mention at the start of this entry.

PPS 10 September 2010, later: Jason Mittell completely understood this entry. If you think that I’m saying TV isn’t worth studying , please read Jason’s careful piece. (In fact, you could count my discussion of Hennesey as an argument for studying TV!)

PPPS 11 September 2010: In my roll-call of TV that Kristin and I watched, how could I have forgotten our devotion to Twin Peaks (1990-1991)? I think I neglected to mention it because we didn’t consider of a piece with ordinary TV. We wanted to follow David Lynch’s career, and we considered the show an extension of his movies. Besides, the series showed the symptoms I diagnosed I mentioned above: episodes fluctuated in quality, and although I liked the later part of the second season better than many people did, its finale was a letdown for me too. For Kristin’s thoughts on Twin Peaks as TV’s equivalent to “art cinema,” see her Storytelling in Film and Television.

PPPPS 5 May 2011: Jackie Cooper died yesterday. The Times obituary glancingly mentions Hennesey, but ignores its real achievements.

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.

Her design for living

Kristin in Rome, 1997, in front of a “recent” hand from a colossal statue of Constantine. The Amarna statuary fragments she studies are twice as old.

DB here:

Kristin is in the spotlight today, and why not? She’s too modest to boast about all the good things coming her way, but I have no shame.

First, our web tsarina Meg Hamel recently installed, in the column on the left, Kristin’s 1985 book Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market 1907-1934. It was never really available in the US and went out of print fairly quickly. Vito Adriaensens of Antwerp kindly scanned it to pdf and made it available for us. So we make it available to you. More about Exporting Entertainment later.

Second, Kristin is not only a film historian but a scholar of ancient Egyptian art, specifically of the Amarna period. (These are the years of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and their highly unsuccessful experiment in monotheism.) Every year she goes to Egypt to participate in an expedition that maps and excavates the city of Amarna. In recent years she’s focused on statuary, about which she’s given papers and published articles. Now we’ve learned that she has won a Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fellowship to work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection for a month during the next academic year. So at some point then we’ll both be blogging from NYC. Think of the RKO Radio tower sending our signals to a tiny world below.

Third, she is about to turn 60, and in her honor the Communication Arts Department is sponsoring a day-long symposium. On 1 May we’ll be hosting Henry Jenkins, Charlie Keil, Janet Staiger, and Yuri Tsivian to give talks on topics related to her career interests. Kristin’s talk will survey her Egyptological work, with observations on how she has applied analytical methods she developed in her film research. You can get all the information about the event, as well as find places to stay in Madison, here.

Kristin came to Madison in 1973, a very good moment. Whatever you were interested in, from radical politics to chess to necromancy (there was a witchcraft paraphernalia shop off State Street), you could find plenty of people to obsess with you. Film was one such obsession.

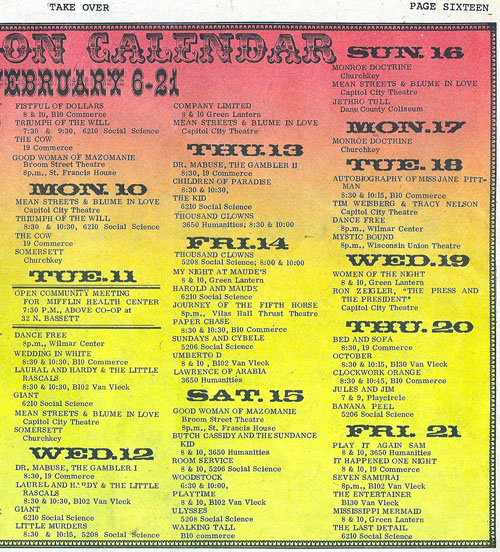

The campus boasted about twenty registered film societies, some screening several shows a week. Fertile Valley, the Green Lantern, Wisconsin Film Society, Hal 2000, and many others came and went, showing 16mm films in big classrooms in those days before home video. Without the internet, publicity was executed through posters stapled to kiosks, and the fight for space could get rough. Posters were torn down or set on fire; a charred kiosk was a common sight. Another trick was to call up distributors and cancel your rivals’ bookings. One film-club macher reported that a competitor had cut his brake-lines.

What could you see? A sample is above. What it doesn’t show is that in an earlier weekend of February of 1975, your menu included Take the Money and Run, The Lovers, Ray’s The Adversary, Page of Madness, Fritz the Cat, The Ruling Class, Dovzhenko’s Shors, Chaney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, American Graffiti, Wedding in Blood, Pat and Mike, Camille, Yojimbo, Faces, Days and Nights in the Forest, King of Hearts (a perennial), Sahara, The Fox, Day of the Jackal, Dumbo, Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, Slaughterhouse-Five, Mean Streets, A Fistful of Dollars, Triumph of the Will, and The Cow. Not counting the films we were showing in our courses.

In addition, there was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, recently endowed with thousands of prints of classic Warners, RKO, and Monogram titles. (There were also TV shows, thousands of document files, and nearly two million still photos.) When Kristin got here she immediately signed up to watch all those items she had been dying to see. She suggested that the Center needed flatbed viewers to do justice to the collection, and director Tino Balio promptly bought some. Those Steenbecks are still in use.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Above all there were the people. The department had only three film studies profs–Tino, Russell Merritt, and me–though eventually Jeanne Allen and Joe Anderson joined us. Posses of other experts were roaming the streets, running film societies, writing for The Daily Cardinal, authoring books, and editing the Light Trap. Who? Russell Campbell, John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tom Flinn, Tim Onosko, Gerry Perry, Danny Peary, Pat McGilligan, Mark Bergman, Sid Chatterjee, Richard Lippe, Harry Reed, Michael Wilmington, Joe McBride, Karyn Kay, Reid Rosefelt, Dean Kuehn, Samantha Coughlin, and Bill Banning. Most of these were undergraduates, but Maureen Turim and Diane Waldman and Douglas Gomery and Frank Scheide and Peter Lehman and Marilyn Campbell and Roxanne Glasberg and other grad students could be found hanging out with them. A great many of this crew went on to careers as writers, teachers, scholars, programmers, filmmakers, and film entrepreneurs.

Into the mix went film artists like Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, and Michelle Citron. There were film collectors too; one owned a 70mm print of 2001 and didn’t care that he could never screen it. ZAZ, aka the Zucker brothers and Jim Abrahams, were concocting Kentucky Fried Theater. Andrew Bergman had recently published We’re in the Money, and soon Werner Herzog would be in Plainfield waiting for Errol Morris to help him dig up Ed Gein’s grave. Set it all to the musical stylings of R. Cameron Monschein, who once led an orchestra the whole frenzied way through Intolerance. The 70s in Madison were more than disco and the oil embargo. (To catch up on some Mad City movie folk, go here.)

These young bravos worked with the same manic passion as today’s bloggers. The purpose wasn’t profit, but living in sin with the movies. Film society mavens drove to Chicago for 48-hour marathons mounted by distributors. Traditions and cults sprang up: Sam Fuller double features, noir weekends, hours of debates in programming committees. Why couldn’t Curtiz be seen as the equal of Hawks? Why weren’t more Siodmak Universals available for rental? Was Johnny Guitar the best movie ever made, or just one of the three best?

There was local pride as well. Nick Ray had come from Wisconsin, and so had Joseph Losey, not to mention Orson Welles (who claimed, however, that he was conceived in Buenos Aires and thus Latin American). During my job interview, Ray came to visit wearing an eye patch. It shifted from eye to eye as lighting conditions changed. When he showed a student how to set up a shot, he bent over the viewfinder and lifted the patch to peer in. Was he saving one eye just for shooting?

In the big world outside, modern film studies was emerging and incorporating theories coming from Paris and London. Partly in order to teach myself what was going on, I mounted courses centering on semiotics, structuralism, Russian Formalism, and Marxist/ feminist ideological critique.

Back in placid Iowa City, where Kristin got her MA in film studies and I my Ph.D., we grad students had seen our mission clearly. Steeped in theory, we pledged to make film studies something intellectually serious: a genuine research enterprise, not mere cinephilia. Madison was the perfect challenge. Here cinephilia was raised to the level of thermonuclear negotiation, backed with batteries of memos, scripts, and scenes from obscure B-pictures. Confronted with a maniacal film culture and a vast archive, Kristin and I realized that there was so much to know–so many films, so much historical context–that any theory might be killed by the right fact.

Watch a broad range of movies; look as closely as you can at the films and their proximate and pertinent contexts; build your generalizations with an eye on the details. Our aim became a mixture of analysis, historical research, and theories sensitively contoured to both. The noisy irreverence of Mad City, where a former SDS leader had just been elected mayor and city alders could be arrested for setting bonfires on Halloween, wouldn’t let you stay stuffy long.

Kristin’s work in film studies would be instantly recognizable to humanists studying the arts. Essentially, she tries to get to know a film as intimately as possible, in its formal dimensions–its use of plot and story, its manipulations of film technique. I suppose she’s best known for developing a perspective she called Neoformalism, an extension of ideas from the Russian Formalists. Armed with these theories, she has studied principles of narrative in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. She has probed film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and her sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. And she has examined narrative and style together in her book on Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible and the essays in Breaking the Glass Armor.

Contrary to what commonsense understanding of “formalism” implies, she has always framed her questions about form and style in a historical context. She situates classic and contemporary Hollywood within changes in the film industry–the development of early storytelling out of theatre and literature, or current trends responding to franchises and tentpole films. For her, Lubitsch’s silent work links the older-style postwar German cinema and the more innovative techniques of Hollywood. She situates Tati, Ozu, Eisenstein, and other directors in the broad context of international developments, while keeping a focus on their unique uses of the film medium.

Perhaps her most ambitious accomplishment in this vein is her contribution to Film History: An Introduction. She wrote most of the book’s first half, and though I’m aware of the faults of my sections, I find hers splendid. After twenty years of research, she produced the most nuanced account we have yet seen of the international development of artistic trends in American and European silent film.

Kristin has also illuminated the history of the international film industry. Everybody knows that Hollywood dominates world film markets. The interesting question is: How did this happen? Exporting Entertainment provides some surprising answers by situating film traffic in the context of international trade and changing business strategies. One twist: the importance of the Latin American market. The book also opened up inquiry into “Film Europe,” a 1920s international trend that tried to block Hollywood’s power. In all, Exporting Entertainment led other researchers to pursue the question of film trade, and I was gratified to see that Sir David Puttnam’s diagnosis of the European film industry, Undeclared War, made use of Kristin’s research.

More recently, Kristin has turned her attention to the contemporary industry, the main result of which has been The Frodo Franchise, a study of how a tentpole trilogy and its ancillaries were made, marketed, and consumed. Her love of Tolkien and her respect for Peter Jackson’s desire to do LotR justice led her to study this massive enterprise as an example of moviemaking in the age of winning the weekend and satisfying fans on the internet. She maintains her Frodo Franchise blog on a wing of this site.

Most readers of this blog know Kristin as a film scholar. They may be surprised to learn that she also wrote a book on P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster books. Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes; or, Le Mot Juste is a remarkable piece of literary criticism. Here she shows how Wodehouse developed his own templates for plot structure and style. Again, the analysis is grounded in research–in this case, among Wodehouse’s papers. So assiduously did she plumb Plum that she became the official archivist of the Wodehouse estate. This is also, page for page, the funniest book she has yet written.

Her Egyptological work is no joke, though, and she has become one of the world’s experts on Amarna statues. She has published articles and given talks at the British Museum and other venues. Soon she’ll trek off for her ninth season at Amarna. There, joined by her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan, she’ll study the thousands of fragments that she’s registered in the workroom seen above. It’s preparation for a hefty tome on the statuary in the ancient city.

You can learn more about Kristin’s career here, in her own words. These are mine, and extravagant as they are, they don’t do justice to her searching intelligence, her persistent effort to answer hard questions, and her patience in putting up with my follies and delusions. You’d be welcome to visit her symposium and see her, and people who admire her, in action. While you’re here, you can watch a restored print of Design for Living, by one of her favorite directors, screening at our Cinematheque. In 35mm, of course. We can’t shame our heritage.

Poster design by Heather Heckman. Check out our Facebook page too.