Archive for the 'Virtual Reality' Category

Venice 2018 College cinema: Landscapes, portraits

Press conference for Biennale College Cinema and VR.

DB here:

As happened last year, I was invited to participate in the Biennale College Cinema Panel. This was the seventh year of the program, which supports the making of low-budget feature films by young people. Proposals, numbering in the hundreds, are reviewed, and out of those several projects are developed in workshops. After development, three projects are chosen for funding, to the tune of 150,000 euros each. You can read details of the program here.

It’s remarkable how much these filmmakers manage to do on this budget. Both last year and this year, I was impressed by the ambition and panache displayed in the films. None of the directors or producers are novices; many have extensive experience in media. Still, to make a feature is a massive accomplishment, and the flair and professionalism on display in the trio of films was heartening.

I was lucky to join a team of pros. Under the direction of Peter Cowie and Savina Neirotti, our group included Glenn Kenny, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, Chris Vognar, and Stephanie Zacharek. Our task was, refreshingly, not to award prizes but simply to offer responses to the finished works. All these writers are steeped in modern and classic cinema, and they’re eager to share their experience with new talent.

One theme that emerged from our public session was the idea that all three films emphasized the slow revelation of character over rapid, audience-engaging plots. Very much in the tradition of European “art cinema,” they aim to entice us with intriguing, sometimes mysterious and contradictory individuals. We watch those individuals confront situations in which their personalities can be revealed or can undergo change. So the filmmaker’s problem becomes: How to create drama out of character?

Into the woods

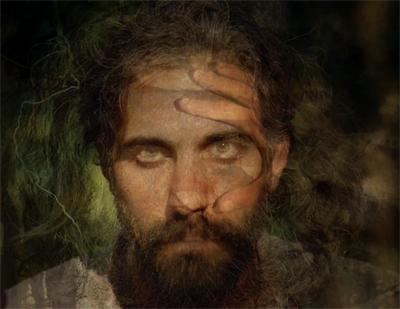

The most mythlike film was Yuva, by Emre Yeksan of Turkey. We’re plunged into a lush forest landscape, and in extreme long shot we glimpse a shaggy figure bearing a carcass (pig? dog?) into an opening guarded by fallen branches. Is it a shelter, or a passageway to another realm? Both, as it turns out.

Without the familiar signposts–no backstory, no titles identifying time or place–and confronting a wordless protagonist, we’re obliged to pay attention to details of what we see and hear. As in many character-centered films, dramatic buildup is replaced by details of daily routines. In this case, our protagonist Veysel explores the forest, finds a stricken bird he tries to revive, and–now traditional drama starts–spies uniformed guards on patrol.

Another film would have started by showing logging companies slashing their way through the forest, immediately establishing a conflict. Here, we’re given the guards, the whine of a woodchipper offscreen, the thrashing of helicopters above, and anonymous hands painting red X’s on trees to be felled. We have to conjure up a drama out of fragments. Even the closer shots tend to keep the landscape on our minds, not least in hallucinatory images.

As the film goes on, we see Veysel slapping mud over the red crosses while evading the patrols. We meet new characters: a stricken woman Veysel carries to the secret shelter, and his brother Hasan, who has come to take him away because the mysterious patrolmen say “they’ll kill you if you don’t leave.” So suspense eventually emerges, but always subordinate to the concrete spectacle of mysterious behavior on the part of our protagonist. The climactic revelation of where that burrow leads pushes the film to a more mystical level. Yuva‘s enigmas of characterization are in the service of broader themes about sanctuary and rebirth.

Born in a cemetery

If Yuva is a landscape-based film, Deva, by Hungarian director Petra Szöcs, is more of a portrait. True, the title refers to the town in Romania where the action occurs, but it concentrates on Kato, a teenager with albinism who is adjusting to life in an orphanage.

Again, character emerges from routines. On her “free day,” Kato shops and smokes and experiments with harsh makeup. She also surprises us. “I was born in a cemetery.” “I killed a boy because he mocked me.” We assume she’s displaying bravado, but either way she engages us as a person before any highly dramatic action is launched.

Still, a plot does develop, centering on Kato’s relationships with her caregivers, infused by her belief in her magical powers. When the attractive and sympathetic Bogi joins the orphanage staff, Kato is drawn to her, and Bogi befriends her–to the point of allowing an indiscretion that will jeopardize their relationship and Bogi’s job. Kato also helps mastermind a piece of mischief that will discredit Anna, a less popular teacher.

Yuva favors distant shots and long takes, but in Deva, Szöcs relies on tight framings and layers of depth (often out of focus) to fragment her scenes. Faces and dialogue are often kept offscreen, the better to concentrate on Kato’s fascinating face and gestures.

Deva‘s laconic style itself becomes a source of curiosity for us, as bits of connective tissue are left out and we’re obliged to appraise the changes in Kato’s character. Our curiosity is enhanced by the performance of Csengelle Nagy as Kato, which is riveting in its sobriety and contrasts with the warm and extroverted Boglárka Komán in the role of Bogi. Again, narrative engagement emerges from the mysteries of personality rather than the pressures of an external situation.

On ice

I know it sounds too neat, but to some extent the landscape and portrait impulses find a balance in Zen in the Ice Rift, directed by Margherita Ferri. The action takes place in the majestic, somewhat menacing Italian Apennines, where Maia, nicknamed Zen, lives with her mother. As the only girl on the ice hockey team, Zen is mocked as a lesbian, and she has become hardened to the bullying she encounters. With her butch-flip hairdo and perpetual frown, she has a hair-trigger temper and all but begs people to fight with her.

One screenplay stratagem for gaining audience sympathy is to have your protagonist treated unfairly. This happens early on, when Zen is slammed by a player on the ice. She reacts by firing a BB pistoal at her loitering teammates. They get payback by locking her neck to a railing. Voilà: a sympathetic but imperfect protagonist, someone we can watch with keen interest as she must make decisions, bad or good.

Those decisions include accepting overtures of intimacy from Vanessa, the prototype of the beautiful, popular teenager. Zen’s sexual identity, confused from the outset, becomes the focus of the drama. This process develops in unexpected directions and leads to a climax that exhibits how teenagers’ use of social media can take bullying to a brutal level.

When Zen’s coach tells her at the beginning that she had a chance to try out for the national woman’s hockey team, I briefly thought we were going to get a sports film, in which the protagonist undergoes the rigors of training and the test of competition. No such thing. The focus is on Zen’s place in the world of teenagers. Her hockey talent is one part of her personality, not the source of goals and conflicts and ultimate triumphs, let alone “life lessons.”

Yet the sports element isn’t gratuitous. Ice becomes a metaphor in the course of the film, as insert shots show glaciers cracking while Zen is forced to confront her still-developing identity. At the end, when she takes to the rink in a burst of solitary confidence, we realize that her defiance hasn’t diminished. Zen in the Ice Rift shows how the drama of character can unfold in both a social setting and the larger milieu.

In addition to the feature films at the Biennale College, there were four Virtual Reality projects associated with the program. The three I saw explored aspects of VR as a medium: awkward intimacy in Metro Veinte, the sense of sinister enclosure in Elegy (aka VRtigo), and the possibility of sampling an eerie landscape in Flood Plain, which extends the narrative situation and imagery of Yuva. At the same time, I thought that they would have made interesting films–which probably indicates that I see rather close affinities between VR and cinema.

Major differences, of course, include VR’s absence of a frame and the possibility of self-willed exploration. As members of our panel suggested, VR creators will need to find ways to motivate the presence of an onlooker in the virtual space, and, if storytelling is the goal of a project, to guide the viewer to salient elements. Narrative, we’ve known since forever, depends on controlling attention.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale. Thanks also to my colleagues on the panel for lively movie talk throughout our stay.

Last year’s College visit is discussed here, and my earlier journey into VR here.

Make the world go away: Venice Biennale VR theatre at Lazzaretto Vecchio.

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or, what puts the Virtual in VR?

La Camera Insabbiata (2017) by Laurie Anderson and Hsin-chien Huang.

DB here (still at the Mostra):

Kristin and I are Virtual Reality novices, so when we got a chance to sample some pieces at Venice VR, we jumped. The demand was great for the 22 pieces on display, and you had to book each encounter separately in advance. The event was held on its own island, Lazzaretto Vecchio, which was startling in itself; the facility was once a hospital for plague victims.

We took in four pieces in one afternoon and may go back to see some others. We didn’t see exactly the same ones, so my report and speculations are limited to mine. Apart from being fairly wild, sometimes creepy, sensory experiences, they set me thinking about how VR seems to work as a medium.

Angels of artifice

My quartet was a varied assortment, each somewhat parallel to a film genre or narrative prototype. The first was Greenland Melting, by Catherine Upin, Julia Cort, Nonny de la Peña, and Raney Aronson-Rath. It’s part of a Frontline documentary series, and it follows the format, but with immersion. Presenters addressed the camera (me) and took me via helicopter to the glaciers so I could watch them heaving themselves into the sea.

The camera took me underwater as well, and I experimented with voluntarily bobbing under and above the waterline; it worked. Again, as in a film, the transitions between shots was managed through quick dissolves.

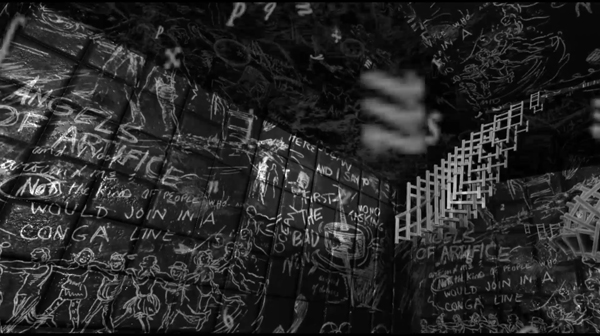

La Camera Isabbiata, by Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chin Huang, is an installation running 20 minutes. It presents a fantasy landscape that you can move through. With two controllers, one in each hand, you choose one of several virtual domains to explore. As far as I could tell, all of them were based on cavernous arrays of blackboards chalked with graffiti. (See the image surmounting today’s entry.)

I first chose the sound domain, which asked me to speak. My words were not only played back to me, but then assumed vase or candy-bowl shapes of gleaming color.

Getting bored with hearing myself and seeing my words made solid, I switched to flying.

Flying was most excellent. Once I figured out how the remotes governed direction, speed, and angle, I could steer a swift path through, over, and around those huge black surfaces. The sense of self-initiated optical flow was powerful, although there were no other cues (e.g., balance, air pressure) to mimic actual flight. But I could have fun playing with this a long time. This was pure subjective POV cinema, or first-person gameplay if you like, and everything was one single shot.

If La Camera Isabbiata put the onus on the user to initiate everything, Draw Me Close: A Memoir by Jordan Tannahill, made me respond to a situation. Once the goggles went on, I was guided to a black-and-white broken-line image of a woman on her sickbed. The artist’s voice-over presented the situation of his mother, dying of cancer, and me-as-him visiting her. Unseen by me, except as her avatar in the goggles, a performer filled the role of the mother, occasionally taking my hand and responding to my responses with more or less scripted comments.

I made my way to a cartoon bed and actually sat on it. The illustrated woman spoke to me, with Tannahill’s voice-over responding. On instructions, I went outside to fetch her paper, but coming back in I moved into a flashback of Tannahill (me) as a little boy playing with Mum. She chatted with me and I feebly responded, and followed her instructions to make colored marks on paper stretched out on the floor.

Later that night Tannahill’s narration guided me to a more unpleasant memory, one reminiscent of Terence Davies’ Distant Voice, Still Lives. It was a minimal narrative to match the images, but I could fill it thanks to the familiarity of the scenario and the tactility of furnishings (bed, door) and physical human contact.

The Deserted, a 55-minute piece, was frankly billed as “a film by Tsai Ming-liang.” A series of fixed long-shots joined by cuts shows a typical Tsai situation: a young man and his mother live in a ruined temple. He apparently administers electrotherapy to his back and chest; he floats in his bath with a fish; it rains in buckets and water comes seeping in to where you’re hovering. A woman in white, perhaps a ghost, appears at times, once in the man’s bathtub.

You make the choices in La Camera Isabbiata, and you role-play in Draw Me Close, but in The Deserted you’re locked down as a witness. No images from the piece seem to be available, but this, from a shot of a camera monitor, roughly indicates the film’s first shot (which isn’t as distorted as this looks).

You can’t move to another spot, and you can’t even crane your neck to peek around corners. You can swivel your head to look 360 degrees horizontally and vertically. But nothing much happens behind your back or over your head. All the action, such as it is, takes place squarely in front of you. Given Tsai’s penchant for static long takes and deep areas of space, The Deserted isn’t putting you inside a real or virtual space; it’s putting you inside a Tsai film.

Reality has the most bandwidth

Since I’m no expert on VR, all I have are initial observations based on this sampling and on a bit of reading.

First observation: VR doesn’t have to be photorealistic to engage you. The image in Draw Me Close is quite impoverished in terms of real-world cues, and the shots of The Deserted are almost shockingly fuzzy. (Tsai, a fan of razor-sharp focus, would never let them in one of his film films.) Other pieces in Venice VR, visible on monitors while users were getting the full dose, are often quite cartoonish. Why are they then so compelling?

E. H. Gombrich suggested long ago that illusion can rely more on stimulation than simulation. That is, choose just a few sensory triggers and you’ll be aroused even if the image isn’t particularly lifelike. Baby geese can, if primed properly, take a box for their mothers, and frogs can snap at anything floating in a fly-ish sort of way around their heads. Outlines, it seems, are central for creatures like us, but they don’t have to be detailed. We also respond, fast and stupidly, to configurations that suggest faces.

Try not to see Jesus, or Janis Joplin, in the tortilla, or a stare on the wings of a Caligo butterfly.

As caricaturists and camouflagers know, a few distinctive features can suffice to summon up the target, and the same goes for the partial and degraded input we see in Draw Me Close and The Deserted. In addition, concepts play a role; our ideas about what to expect in certain surroundings, such as a household, help the illusion cohere. And the information needs to be consistent. When I turn my head in Tsai’s temple, nothing I see contradicts the other cues.

A second point: The VR experiences subtract on some channels of input and compensate on others. Normally, perceptual reality is massively redundant. Our sensory systems reinforce one another. Tilting your head sends signals about balance and vision, while sight and sound and touch and muscular activity offer mutually confirming information. And when things are uncertain, you can always test your environment by moving around.

But the VR systems I encountered impoverish the input on certain channels. Standing in the helicopter of Greenland Melting, I saw the passenger seat beside me as vividly three-dimensional, but when I tried to grab it for support, nothing was there. In The Deserted, I looked down and didn’t see my feet; in fact I was an eye in a bubble floating midway up the wall, where the camera was. And in neither of these pieces could I move voluntarily to poke around much in the space.

I could do that in La Camera Insabbiata, but it was an impoverished environment along other parameters. I could fly, but not touch any of the surfaces–which were without color or shadow, beyond a spotlight that shifted to follow my attention (presumably guided by eye-tracking software). I couldn’t land atop one one of the monoliths, or bump into an edge.

Reciprocally, Draw Me Close provided other sensory inputs: locomotion (though not wholly voluntary), touch (initiated by the performer playing Mum, and by the prop bed and door), and an array of skimpy visual-spatial cues. In principle, smell could have been included. Why not, then, go the whole hog and use a photorealistic rendering of the space and Tannahill’s mother? Perhaps a very faithful representation of Mum and the household would have raised the problem of the Uncanny Valley.

Just as important, we might ask: Since a performer is always required for the piece, why not simply play out the scenes with her and the user? Just go for reality, not virtual reality. I’m guessing that the move toward drawn imagery marks the project as stylized enough to be a media artifact, rather than a piece of interactive theatre. (Though it is partly that.) Here, I’m thinking, the impoverishment of information on certain channels was a deliberate aesthetic choice, rather than being obligated by computer processing power, though that would probably have been a factor too.

One of the biggest compensations for what’s missing in some channels would seem to be good old peripheral vision. This is a very strong cue to immersion, and it can override inputs that contradict it. I remember being in one of the Disney World attractions back in the 1980s, a wraparound theatre that put visitors at the center of a travelogue. Even though there were plenty of cues that you weren’t in front of Buckingham Palace–such as your awareness of people around you looking in different directions–if you concentrated on the filmed display, there was a compelling illusion that you were riding down the street toward the Palace.

Peripheral vision would seem to be a powerful sensory trigger for creatures like us. This was the insight that drove widescreen cinema and the curved screen of Cinerama. But efforts to activate peripheral vision maximally come at a cost. You lose the frame and thus a sense of significantly composed imagery. The Disney display had, as I recall, borders at top and bottom, but in modern VR those too are abolished. VR gives with one hand and takes away with the other, so to speak: Greater immersion yields less of the pictorial structuring that’s inherent in framing. Tsai’s film somewhat overcomes this problem by making the surrounding space neutral and fairly uninformative, but the result still loses the sharp dynamic of offscreen and onscreen space we find in his feature films.

One more thought, which seems more solid than the others. Some have asked whether VR can accommodate narrative. I had presumed so theoretically, but now I’m convinced. Greenland Melting told a real-world story, an alarming one at that. Draw Me Close had emotion-laden scenes, a crisis and climax, and a flashback. The Deserted presented a typical Tsai scenario of humid stasis–a thin narrative, but a narrative. (As often in Tsai, what we miss in psychology and causal density we get in slight spatial changes and pictorial surprises.) It wouldn’t be hard to “narrativize” the Camera Insabbiata soaring, either, say by prodding me to go on a cosmic scavenger hunt. I conclude that of course VR can deal with narrative.

John Landis worried that VR was too wedded to long takes to suit cinematic storytelling. That worry was in turn tied to the assumption that narratives must guide your attention. True! But it’s wrong to assume that only continuity editing can shape a film story. Our attention can be precisely guided through long takes. Indeed, to a degree the sort of open and exploratory attitude some find in VR was already there in locked-down long-take directors like Mizoguchi, Akerman, Hou, and Tsai. And they told stories, plenty of good ones.

Many thanks to Peter Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michela Lazzarin, and all of their colleagues for inviting and assisting us. Special thanks to Andrea Vesentini for guiding us through the array of events at Venice VR.

For details on Venice VR, go here. Variety covers the Venice event in articles by Elsa Keslassy and Nick Vivarelli. Patrick Frater interviews Tsai on The Deserted here. I found this Wired piece a good VR primer, and Ty Burr offers an update in MIT Technology Review.

Gombrich’s key essay on simulation and stimulation is “Illusion and Art,” available without illustrations here. In full form it appeats in Illusion in Nature and Art, edited by Gombrich and Richard L. Gregory (Scribners, 1973), 193-243.

For discussions of how storytelling cinema guides attention within the shot, see the categories Film Technique: Staging and Tableau Staging.

Better than a cellphone? Viewers at Venice VR.