Monday | October 10, 2022

Kristin here:

Regular readers of this blog may remember that back in early May I posted an entry trying to answer, at least to my own satisfaction, the question “How did ‘prestige horror’ come about?” As I wrote at the time, the piece wasn’t motivated by any particular interest in the horror genre. Instead it resulted from the confluence of three films considered to be in that category being released during the summer season: The Northman, Men, and Nope, all by interesting directors. That’s when I discovered the phenomenon of prestige horror as a trope among reviewers. I also discovered that the indie producer-distributor A24 has been a major contributor to the small group of films usually mentioned when anyone writes about prestige horror. (For a good summary of A24’s impact on the horror genre, see here.)

Later, having seen A24’s next release, Alex Garland’s Men and quite liked it, I read some uncomprehending and dismissive reviews of it. (These were largely from mainstream critics; horror buffs who wrote about it tended to “get it.”) I decided to analyze this challenging film and posted the result here.

Two days before Men was released on May 20, Variety Intelligence Platform posted an article by Kaare Eriksen, “Can A24 sustain its box office boom?” (This specialty wing of Variety is behind a pay wall; for those who subscribe, find it here.) Everything Everywhere All at Once was already about six weeks into its unexpectedly lucrative run. Eriksen commented of A24, “Its next film, ‘Men,’ which releases nationwide on Friday, may extend this momentum.”

Not surprisingly, Men did not extend that momentum. As Eriksen points out, it was made on a small budget–though how small we don’t know, as I have seen no figures on the cost of the production. Its worldwide gross of a little over $11 million seems unlikely to have made it even slightly profitable. It appeared on streaming services not long after the film went out of theatrical circulation, which was not typical of A24’s approach. Ordinarily they have left a longer window between theatrical and streaming. Men quickly became available as VOD from several services. How much it made in that fashion is unknown.

I wondered how much impact the failure of Men would have on A24’s financial well-being and decided to find out. It turns out, not much. Perhaps the studio’s head will move away from prestige horror a bit, but A24 was never a specialist in horror in the way Blumhouse is. A24’s films have ranged from high-profile Oscar winners like Room and Moonlight to the modest animated feature Marcel the Shell with Shoes on (bottom). It isn’t shying away from more conventional horror films as the recent releases of X, Bodies, Bodies, Bodies, and Pearl show.

[October 31: Will Pearl boost Ti West’s series into the prestige horror category? (The series will become a trilogy with MaXXXine.) As with Ari Astra’s films, Martin Scorsese has again gained A24 attention by describing his reaction to Pearl: “I was enthralled, then disturbed, then so unsettled that I had trouble getting to sleep. But I couldn’t stop watching.” Several news outlets covered his laudatory remarks.]

Festivals and awards

There’s nothing like a premiere at a major film festival or the bestowal of a big award to signal prestige. I mentioned in my prestige-horror piece that A24 had films in that sub-genre premiere at SXSW (Ex Machina, which also won a visual effects Oscar) and Sundance (The Witch). This year the studio took a leap upward with three films premiering at the Venice International Film Festival (above, from A24’s twitter page). Two were in competition: The Whale, by Darren Aronofsky, and The Eternal Daughter, by Joanna Hogg. One premiered out of competition: Pearl, by Ti West, an origin story for and sequel to X (2022).

Festival director Alberto Barbera, asked about blockbuster films at this year’s festival, said: “We had discussions with all the studios. There wasn’t really a blockbuster similar to Joker or Dune, but we still have great presence from the U.S. studios: WB, Sony, Searchlight, Universal, Netflix, Amazon. And for the first time we have two films from A24. I’m really glad we could make it work with them and hope it’s the first of many collaborations.” Barbera is presumably talking about the number of films in competition. Apparently he is anticipating future A24 films on upcoming programs. None of A24’s films won an award at the festival, though one result was that Brendan Fraser has joined the Oscar buzz for a best-actor nomination.

A24’s The Inspection, a film about a gay Black man determined to join the Marines, was chosen as the closing film at the New York Film Festival on October 14.

It has already played at the Toronto Film Festival.

Will A24 feature among the Oscar nominees? “In Hollywood it’s never too early to start thinking about the Oscars,” as Clayton Davis wrote in a July 28, 2022 article, “Award Season Preview: Despite Industry Changes, Winning Oscars Remains Top Studio Priority.” Studio by studio, he comments on their chances for nominations:

There’s already a pair of populist contenders in Paramount’s blockbuster “Top Gun: Maverick” and A24’s metaverse action-dramedy “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” which have cemented themselves in the best picture discussion.[…] With “Everything Everywhere All at Once” becoming the highest-grossing film in the history of independent studio A24, they may have more capital to play with to get Michelle Yeoh an overdue nomination for best actress. They’ll also give a qualifying run to “The Whale” from “Black Swan” (2010) by Oscar-nominated director Darren Aronofsky, said to have the comeback performance of the year from Brendan Fraser. They’re also partnering with Apple Original Films once again for “Causeway,” formerly “Red, White and Water” from Lila Neugebauer and starring Jennifer Lawrence, who also produces.

Having already started lists of predictions for the top Oscar contenders, Davis puts Everything Everywhere All at Once at number 6 for best picture. (Davis includes films yet to premiere, especially at Toronto.) Michelle Yeoh tops his best-actress category.

[November 4, 2022: Variety‘s Cynthia Littleton has this to say in a recent story on The Whale‘s Oscar chances: “A24, which is releasing ‘The Whale’ in theaters, is known for the NYC swagger that befits a top indie distributor.”]

[December 3, 2022 A24’s films won four awards from the New York Film Critics Circle awards, the highest number won by any studio.]

Other signs of continued prestige include a brief weekly series called “Post-Horror Summer Nights” that recently ran at the Barbicon in London. Two of the four films were from A24: The Witch and Hereditary. Also, A24 has picked up the North American distribution for Close, Lukas Ohont’s Grand Prix winner at Cannes this year.

The brand

A24 probably is the most widely recognized indie studio. It has its own devoted fans, many of them in that younger demographic so beloved of movie producers and exhibitors. It works hard to maintain that brand recognition. Naturally it has its own Facebook and twitter pages and is undoubtedly elsewhere on social media sites I ignore. It also has a podcast. It re-designs its logo in eye-catching ways to fit each film, as with the Green Knight opener above.

A24 has its own line of merchandising, selling limited-edition items. Some bear its logo and others relate to specific films.

As the notes in these examples indicate, the majority of items on the shop page are sold out.

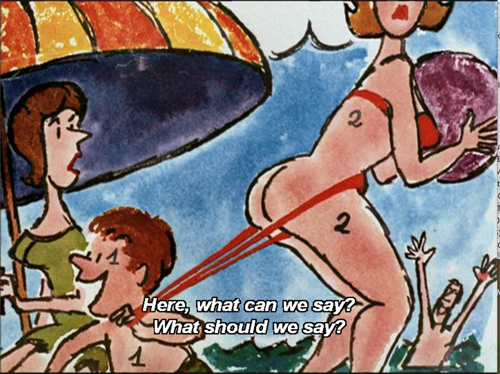

Blu-rays of some of their films, often in fancy collectors’ editions, are available. There are soundtracks as well, only on vinyl. A red-vinyl release of the Men soundtrack with a slipcase “featuring six interchangeable covers with watercolors by Julian Gross” (top). It is not shipping until December, so it’s an iffy choice for a Christmas gift. It’s also apparently the only option if you want the soundtrack on physical media; it is otherwise available only for download.

The items are fairly pricey, though I doubt they affect the studio’s bottom line much. Nevertheless, I suspect that they give fans a feeling of connection with A24 and endow it with a quirky aura that fixes it in people’s minds.

Since they are only sold through the studio’s own shop, at least all the income goes to A24 and not to amazon. Theoretically, that is. Someone bought up a batch of the Green Knight vinyl track (green, naturally), which is now sold out on A24’s shop. That entrepreneur is currently selling them through amazon for $99. The soundtracks originally cost $35 from A24. I guess this is another indication of prestige or at least fan devotion among people potentially willing to purchase a copy despite the considerable markup.

The devotion seems genuinely to be there. In a conversation about “The A24 Effect,” Sam Sanders and Nate Jones are discussing the studio’s skill at marketing films and creating a brand through merchandising:

SS: How much of that is the merch? I don’t think I’ve ever experienced a movie studio in which people in my circles are actually excited about the merch. One of my friends yesterday was raving about his A24 fleece. […] What is that?

NJ: That’s a very big part of it. No one’s walking around in a Focus Features hoodie the way that they are in A24 stuff. It goes back to the marketing, the realization that plugging into these downtown fashion circles is another way to cut through the noise. And they do these limited-edition drops that create this sense of exclusivity that mirrors the way that these films are so treated in the cultural conversation.

Sanders calls A24 “the coolest movie studio around.” The “special recipe” they detect consists of three strands: youth culture, horror, and “auteur-prestige cinema,” such as Room, Lady Bird, and Moonlight.

The finances

Despite the unfortunate failure of Men, A24 is doing quite well.

For one thing, on August 1, HBO Max recently added 28 films from A24 to its offerings, mostly films the company only distributed in its early years. Variety predicts that this list will grow as the studio’s deals with Apple+ and Showtime expire.

More importantly, A24 is expanding based on new investments. On September 1, The Economist took note in an article entitled “The Rise and Rise of A24” (behind a pay wall):

The bosses of A24 declined to talk on the record, coyly hoping their output speaks for itself. It has proved persuasive to financiers as well as awards juries. In March the company was valued at $2.5bn as it took in $225m in investment; the lead investor is Stripes, a private-equity firm that helps businesses grow. The funds will let A24 boost its production capacity. It has opened an office in London (and poached two BBC commissioners); it hopes to make films and TV programmes in other territories soon, possibly in foreign languages.

In Erikson’s “Can A24 Sustain Its Box Office Boom?” (linked above), he mentioned “A24’s reported exploration of a $2.5 billion to $3 billion sale last year, with newer streaming entrant Apple apparently interested at one point. This apparently was a result of the pandemic-related slump rather than any underlying vulnerability on A24’s part.

In another symptom of financial health, in October 2021, A24 signed a 15-year lease on four floors of a major new office building at 1245 Broadway. This building was just finished last month. I presume the studio will soon transfer its headquarters from its current modest headquarters, one floor in 31 West 27th Street, to which it moved in 2015 (above). Given the rather bare-bones appearance of the current office, I presume this is a considerable expansion and a more prestigious location. A24 seems confident that it will be around for quite some time.

I am not a fan of the studio itself, only some of the films it has made. Apparently a common accusation leveled against A24 is that it is pretentious, or its films are, or its fans are. But “pretentious” is a word used freely, depending on the tastes of the person using it. Many of the great filmmakers of cinema history are thought of as pretentious by some. The strengths of A24 are that it is surviving in an industry context where films with modest budgets are struggling in the theatrical market and franchise films dominate. In the same “The A24 Effect” podcast linked above, critic Alison Willmore points out that the studio owns no intellectual property that has generated a franchise and that its films are mostly originals or based on fairly obscure literary sources. This helps account for the considerable variety in the types of films A24 releases. It is good to see an indie studio managing to survive and even thrive these days.

Marcell the Shell with Shoes on (2022)

Posted in Hollywood: The business, Independent American film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on A24: the studio as auteur open printable version

| Comments Off on A24: the studio as auteur

Monday | September 26, 2022

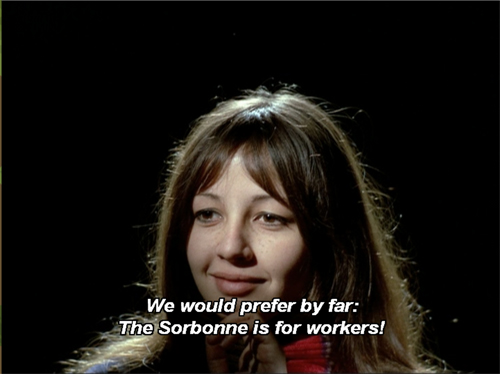

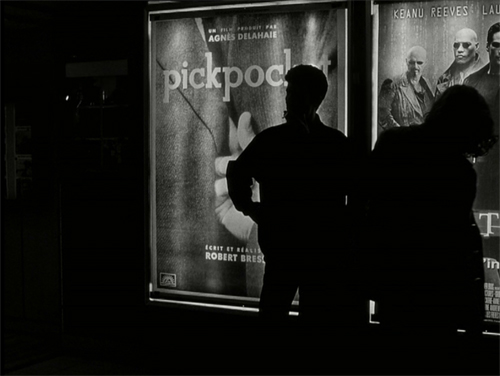

Opening credits of Bande à part (1963).

DB here:

He was a sketchy fellow, to put it mildly. Childhood episodes of theft were followed by larceny as an adult, when he stole his grandfather’s Renoir and swiped cash from the Cahiers du cinéma till. Notorious for taking funding for projects that were never made, he once contracted for $500,000 to create a film on the Museum of Modern Art. He declined to visit the museum and instead shot the footage from stills at home. When The Old Place was finished, he agreed to introduce it in Manhattan. Hours before he was about to fly out (on the Concorde) he canceled, using anti-American cinephilia as his excuse: “I will return to New York when the films of Kiarostami are playing on Broadway.”

He liked to fight. Friends, romantic partners, performers, producers, government officials, and critics all felt his wrath. Jane Fonda was the target of Letter to Jane, a critique of a photograph of her meeting the North Vietnamese. The voice-over narration insisted it was not an attack on her as a person but as a “star.” Breaking with Truffaut led Godard not only to harangue his former pal (“liar”) and the films he made, but demand money so that he could make a film in response to Day for Night. Truffaut’s twenty-page reply called him “a piece of shit on a pedestal.” They never spoke again, and Godard’s remarks after Truffaut’s death praised him as a critic but omitted mention of his films.

Meeting Professor Pluggy

King Lear (1987).

I never had an abrasive encounter with Godard, but I always sensed that he was aloof at best. My first, very brief meeting was in spring of 1973 when he and Jean-Pierre Gorin visited the University of Iowa with Tout va bien (1972). Onstage, he was calm and earnest, while saying fairly provocative things. (Go here for a record of one session.) Asked what he thought of The Godfather, he replied: “The Godfather is shit. But there is a part of me that loves shit.” My eyewitness encounter took place in an elevator, when the host told Godard and Gorin that their schedule now had an empty hour. Godard said: “I am a prostitute. Why do you not use me?”

I had more prolonged exposure to him in 1981, when he visited a lecture series I was giving at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He was touring with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), and the series director Melinda Ward took the opportunity for us to do a career review onstage. I planned to juxtapose clips from his work with those by other directors, and called him at Rolle to review my choices. He listened politely and said they would be fine, adding: “No matter what you choose, it always works.”

The session turned out well, with Godard modest about his efforts compared to those of Preminger (“like Manet”) and others. The only time the audience seemed ruffled was when he said of Jerry Lewis and the clip from The Ladies’ Man: “He is Robert Rauschenberg” (seems reasonable). For a couple of days Kristin and I drove him to interviews around town, and he spent his time reading Variety, noting only that he was pleased that Gance’s Napoleon was doing good business. Attempts to engage him in conversation were fruitless. But once onstage he was alert and genial, all soft speaking and gentle smiles.

The big stir came the following night with the screening of Sauve qui peut. A considerable portion of the audience objected to the film’s sexual politics. The most fraught moment, as I recall it, went like this:

Woman in the audience: Why do you make films only about women prostitutes, not male ones?

JLG (after a pause): They are different things.

Woman: How can you claim to talk about a women prostitute’s life?

JLG: Well, every time I hire a prostitute I ask her about her experiences.

Audience: stunned silence.

My last encounter was the most embarrassing. Invited to a conference on his work at Liège in 1986, I had horrible jet lag. In the first evening, a Q & A with the master, I made the mistake of sitting, as usual, in the front row. The problem was I kept dropping off to sleep. Every time I blinked awake, Godard was staring impassively at me. I thought no one noticed, but afterward one of the conference speakers said: “He was looking at you sleeping all the time.” Jesus.

I consider myself lucky to have escaped the treatment others have reported. Maybe it made it easier for me to admire his work. Yet even that admiration is tempered by exasperation. Bypassing von Stroheim and Buñuel, he might be the most annoying great filmmaker of all.

I’m not referring just to his obsession with female nudity, or his pretentious wordplay, or his pseudo-profundity. His provocation goes all the way down to the very texture of the film. In form and style he embraced irregularity. He will create a scene that’s conventionally beautiful, only to spoil it with a harsh disjunction or a silly gag or a deflating commentary. He seems to want to coax us to enjoy imperfection. His deformations of story and style are the result of testing the limits of what cinema had done, and might do.

Early work: Puncturing the plot

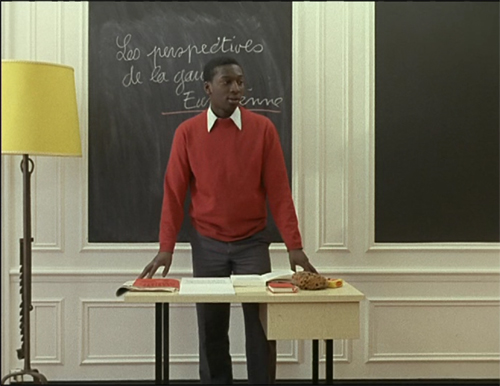

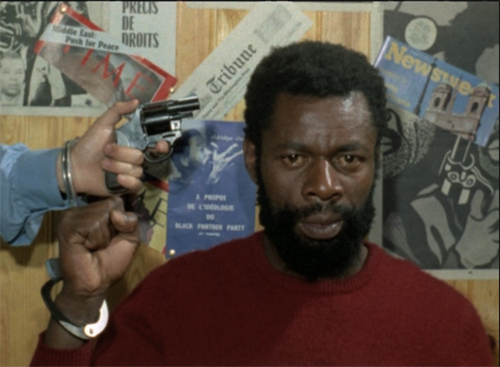

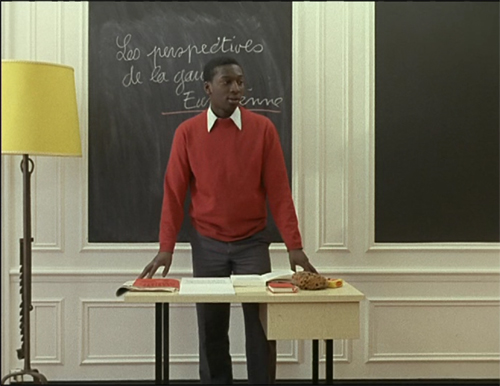

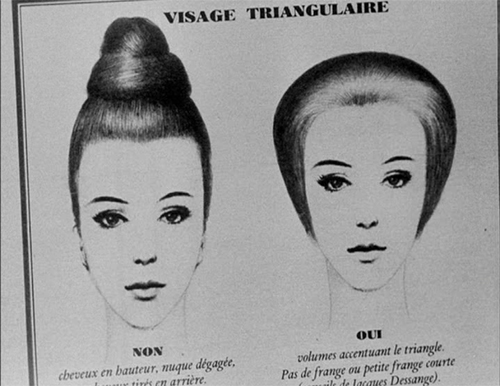

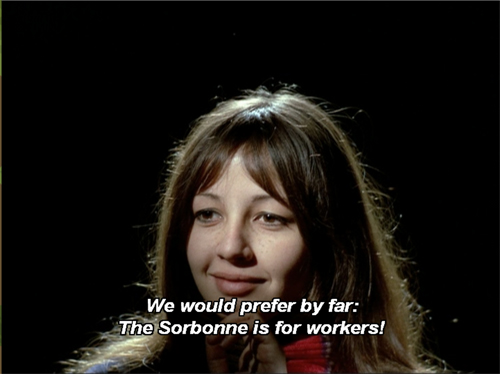

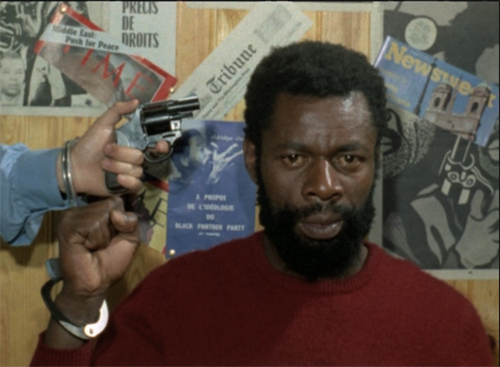

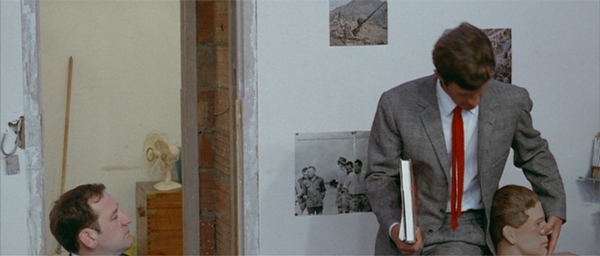

La Chinoise (1967).

Everything about him is troublesome. As a rough approximation, we tend to divide Godard’s career into three parts, but the results are peculiar. The early New Wave period runs from 1959 to 1967. The second, his overtly “agitprop” phase runs until 1980. Then we have “late Godard,” which dates from Sauve qui peut (la vie) until his death this year. What other artist has a “late” period running over forty years?

In all these periods, it’s common to say that Godard attacked, even destroyed, previous forms of cinema. But it helps to specify a bit more. I want to focus on his peculiar relation to narrative.

He often derided Hollywood’s reliance on stories, but throughout his career he depended on them. Asked about Hail Mary, he replied that the Bible had many good stories one could use. The project he proposed to Coppola about Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas was initially titled simply “The Story.” Even the collage form he utilized in his last completed film, The Image Book, ends with a fictional tale about how Sheikh Ben Kadem, ruler of a kingdom called Dofa, tried to resist American imperialism.

One reason his early work succeeded, and survives as a body of classics, is that he relied on narrative conventions of traditional filmmaking. He rummaged through familiar genres: the couple on the run (Breathless, Pierrot le fou), spy intrigue (Le petit soldat), musical comedy (Une femme est une femme), social drama (Vivre sa vie, Two or Things I Know about Her), war picture (Les carabiniers), marital drama (Contempt, Une femme mariée), a robbery scheme (Band of Outsiders), a detective investigation (Alphaville, Made in U.S.A), and young romance (Masculin féminin).

More radically than his New Wave colleagues, Godard transforms these conventions. Sometimes he de-dramatizes intense situations, as in the violence of Le petit soldat and Les carabiniers. More commonly, he punctures the stories with digressions, skits, and uncertainties about character psychology. There’s also often a mockery of the very conventions invoked. Nonetheless the genres provide an armature for the audience to cling to, and the plots wrap up with more or less decisive endings.

With La Chinoise, not only does the plot swerve from traditional genres (I suppose it’s a perverse roommate-relationships story) but the dynamic of the drama becomes overtly rhetorical, with both the characters and the overall narration setting out political theses. Weekend has a narrative core–a couple set out to visit and kill a rich relative–but the familiar journey schema becomes apocalyptic as the bourgeois encounter a world bent on revenge for oppression.

One strategy Godard pursues is to deform narrative by mixing in other formal principles. The later early films introduce passages cast in rhetorical form, as when characters indulge in extensive arguments about philosophy or politics (La Chinoise, Vivre sa vie).

The early work also introduces passages of associational form. More and more often, Godard interrupts the action with cutaways to images that create commentary, analogies, and contrasts. Book titles are the simplest examples, but we also get the shots of fashion advertising interpolated into Une femme mariée and the landscape of consumer goods inserted into Two or Three Things.

With Le gai savoir of 1968, narrative is sidelined altogether as the primary characters conduct a political deciphering of a cascade of mass-media images.

The late 1960s-early 1970s quasi-Maoist films that Godard made with Jean-Pierre Gorin, sometimes under the rubric of the Dziga Vertov group, rely mostly on rhetorical and associational form, as in One Plus One and Pravda. Vladimir and Rosa, however, returns to narrative in providing a caricatural replay of the trial of the Chicago Eight, and Tout va bien is like the early work in embedding its political commentary in a more or less linear plot line.

After the break with Gorin, Godard continued to mix narrative and other formal options in Numéro deux, Ici et ailleurs, and several striking documentaries of the mid-1970s. Seen today, Comment ça va looks ahead to both the style and the construction of his late films in tracing two couples caught up in the politics of the mass media.

Style as rewriting

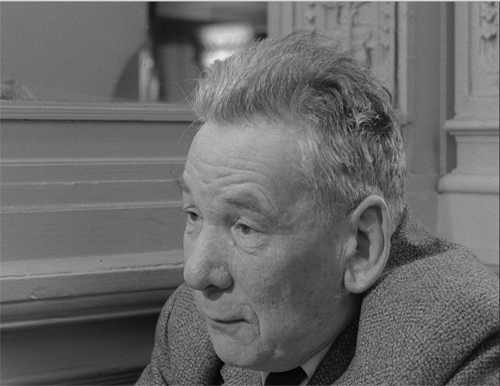

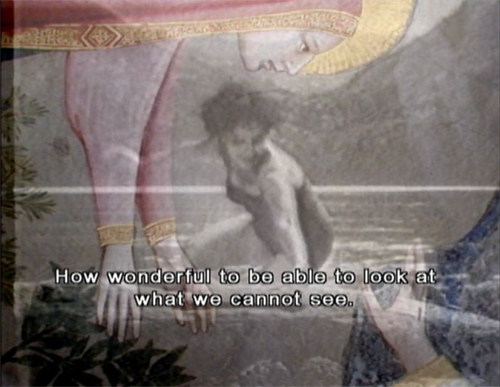

JLG par JLG (1995).

By emphasizing Godard’s reliance on narrative principles I don’t mean to reduce his originality. Like a Cubist painter creating a portrait or a still life, he needs some norms in order to introduce his disturbing deformations. He gives with one hand and takes away with the other, and to feel his work’s disruptive force we need a tacit background of what’s ordinarily done.

The same holds for matters of style. Most scenes in the early films rely on standard continuity, as I tried to show in one chapter of Narration in the Fiction Film. Even a film as fragmentary as Vladimir and Rosa depends on eyeline-match cutting.

Godard’s limited obedience to standard style makes the deviations stand out. In the shots above, the curtain background forestalls expectations of real space. Often the calculated disruptions of continuity have an arbitrary air, as if there’s no particular motivation except the opportunity to try something new. The celebrated jump cuts in Breathless, for example, seem to have no specific functions as motifs or narrative cues. They register as glitches, gratuitously spoiling a shot. Like DJ scratches and skips in hip hop, they come to form percussive passages that can be appreciated for themselves.

The early films try everything: labyrinthine camera movements, shots too short to be grasped, abrupt dropouts of sound and image, wisps of voice-over. Drama could be punctured or entirely suppressed. Alphaville expands a moment of suspense into a lyrical interlude, while Un petit soldat, after arousing our concern for the woman the hero meets, shoves her torture and death offscreen, reported in a tossed-off line of dialogue. All of cinema was simultaneously available to the New Wave directors, who at Langlois’ Cinémathèque saw a Griffith film alongside a Nicholas Ray picture. Godard gleefully ransacked film history, while deforming each device to see what he could make of it.

For example, Godard gave new life to a compositional option I’ve called planimetric framing. The camera shoots figures perpendicular to the background and places those figures frontally or in profile. Earlier it had been an almost ephemeral moment. Godard makes it a stylizing gesture, offering pictorial abstraction that short-circuits naturalistic drama (Pierrot le fou, Two or Three Things I Know about Her, Vladimir and Rosa).

What binds these all stylistic tactics together, I think is a broader narrational strategy. Godard carries the auteur theory to a new limit. In watching the film, we become aware not just of “a narrator” but of a specific agent, Godard the director, who insists that his story world is created and transformed by the practices of cinema. This isn’t just “Brechtian” distancing but persistent signs of this particular filmmaker’s creative work. Godard invites us to admire his sometimes annoying audacity.

The intertitles are the most evident signs of this agent’s activity, but so too are the unrealistic staging, the abstract compositions, the geometric camera movements, and especially the manipulations created in post-production. Sound mixing cuts off noises, muffles dialogue, provides anonymous voice-overs, scatters audio across many channels, and wedges in chunks of music. Post-production is seen as offering the filmmaker’s final, if sometimes inconclusive, revisions of his creation. It’s as if a novel were published as the copy-edited and marked up proofs of the author’s manuscript.

Critics are fond of saying that 1960s Godard changed the language of cinema. That’s sort of true, but we should remember things that were abrasive or alluring in his films have mostly been tamed by their assimilation to mainstream uses. Chapter breaks and intertitles are now recruited to create coherent story connections, as in Tarantino. The handheld camera is commonplace, but it serves chiefly as a wavering substitute for standard framing. His planimetric framings create a painterly abstraction, but in the hands of Wes Anderson they function as seriocomic establishing shots. Today’s directors use jump cuts mostly to compress time between stages of an action, not to annoyingly break the flow. And even our filmmakers who treat auteurism as a brand do not create the sense of the filmmaker’s hand fooling with every image and sound on the fly. Godard’s unpredictable tweaking asks us to adjust to a film that will undercut its own effects.

It makes me revert to a quotation I’ve used before. Supposedly Picasso told Gertrude Stein: “You do something new and then someone comes along and makes it pretty.” It’s worth noting that as mainstream films adopted his early technical tics, Godard abandoned most of them. His later work locks down the camera, favors depth staging over planimetric flatness, and avoids jump cuts. Three separate, disjunctive shots in Hélas pour moi show how he can reinvent continuity jumps, this time to harshly italicize a gesture: departure.

Late films: What the hell is going on?

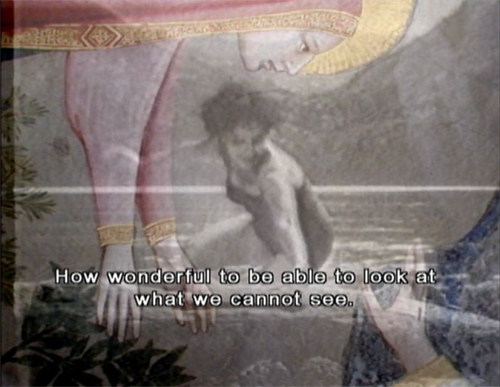

Film Socialisme (2010).

The late films of Godard are tremendously varied, and I can’t claim to have seen, let alone assimilated, all the shorts and medium-length projects. But consider just two main types of features. There are the “film essays,” the prototype being Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998). His last feature, The Image Book, is also an instance.

I’m disinclined to call them essays, since the ones I know don’t coherently marshal evidence to support a line of argument. They’re largely associational collages of found footage, suggesting pictorial or conceptual links among them. If you want a literary analogy, the poetry of Whitman or Pound would be close. The collage films also have rhetorical overtones, presenting ideas about, for instance, the way Hollywood evolved after World War II in Histoire(s). In its mixture of rhetorical and associational patterning, Le gai savoir was a rough prototype for the collage films; they simply delete the characters whose dialogue frames a flurry of images and substitute Godard’s own voice, or a merger of other voices.

I’m in that minority of Godardolators who find the collage films of limited interest. I find the philosophizing often facile, the claims about film history too broad, the politics obscure and even naive. Most essays take opposing views seriously enough to confront them, but Godard doesn’t rebut positions. He contents himself with post-production reworking of the imagery, twiddling the knobs to destabilize the image. As in the early films, his documentary images can’t escape transformation by the all-powerful filmmaker. At the least, comments might be scrawled on the images. But there will also be superimpositions, spasmodic slow motion, and freeze frames. Color values are garishly recast and aspect ratios pinched or stretched (Histoire(s), The Image Book).

The demiurgic filmmaker can’t leave any picture alone. And of course his voice will guide the soundtrack. Other auteurs have a discreet signature; Professor Pluggy, thanks to all those RCA cables, gives us incessant audio graffiti.

For me the triumphs of the late career are the narrative features. Just as the early films deformed norms of classical storytelling, these can be taken as a continuing dialogue with contemporary “art cinema,” that psychologically-driven filmmaking that explores characters’ minds and relationships. While art-cinema narration sometimes challenges the viewer, Godard goes much further.

Again, story entices us. The late films return to situations he has long relied on, usually involving a romantic couple but sometimes also a family, as in the second section of Film Socialisme. There are recurring arcs of action: seduction and courtship, a dissolving couple, an investigation, or an artistic project–recording a song, making a film. There will be at least one long conversation, but also communication through body language, often violence.

The milieu is often that of a workplace–a factory or business, especially that of prostitution or filmmaking. (Passion makes the film studio a parallel setting to the factory.) Godard once said that the most important things in life are love and work, and these concerns supply his late works’ narratives with a recognizable world.

He sometimes provides “braided” plots, tracing two or or more groups of characters, parallel or intersecting. For Ever Mozart bears the label “36 Characters in Search of History.” Such braiding is comparatively rare in his early period. The plot will be partitioned by chapter divisions, but they don’t necessarily mark off portions of a story; just as often they interrupt a scene. Instead of braiding, we may get a sort of geometry, with two or three side-by-side stories–leaving us to sense connections among them. As the late career progresses, I think that those connections become more elusive.

Once we have narrative conventions in place, they can be blocked. Reviewers who confidently sum up a Godard plot don’t do justice to Godard’s astounding resourcefulness in impeding our understanding while still teasing us to try to get it. If the early films interrupt the action, in the later films we have trouble figuring out what the action is.

Bereft of point-of-view shots, visualized memories and dreams, appointments, and deadlines, these films avoid the commonplaces of modern movie storytelling. In that sense his films are “objective” in relying on characters’ behaviors to convey the action. But that behavior is often difficult to understand.

The characters may be unidentified, or inconsistent, or unrealistic in their actions and reactions. Why does the factory boss in Passion carry a rose in his teeth? Where does the twin of Alain Delon come from in Nouvelle Vague? On first seeing Hélas pour moi, I found every image ravishing and every scene baffling.

The most basic exposition about the characters’ relationships is often suppressed. Often you must watch the film several times to figure out kinship and alliances because there is only one hint, not the redundant signaling we get in mainstream cinema. And even when we’ve sorted out the characters’ roles, a scene may not have a clear-cut arc. We might enter the action partway through and leave it before the scene ends.

Part of the difficulty comes from an idiosyncratic style. He favors “troubled” master shots. The action is given a kind of coverage, but with obscure angles, partial framings, and time gaps between shots (alternatively, repetitions of dialogue). The editing of a scene often relies on the Kuleshov effect, with shots of single characters linked through eyelines.

Overall, a scene’s presentation is both sparse and dense. The action is built out of details, but sometimes things get overbusy, with jammed frames and layers of dialogue. And he loves to block our view of faces, by using the frame to decapitate major characters, or to interpose objects that make it hard to understand who’s present, or to tuck faces into apertures.

More blockage: main characters are often turned from us, plunged into shadow, or put out of focus, making expressions difficult to read. Combined with depth staging, these shots challenge us to carve out the prime narrative action (Passion, Éloge de l’amour, Notre musique).

Refusing the Steadicam (and today’s annoying slow track-ins to a character), Godard locks down the camera. He moves his figures through the shot and insists on filling the 1.37 ratio: every zone of space can matter. Any area of the image can harbor a significant gesture or facial expression (Hail Mary, Detective).

Godard’s fastidious attention to the precise image has not prevented him from his characteristic “overwriting” in post-production. The action, inevitably, is interrupted by intertitles. Classical music or ECM samples drop in and out, with a voice-over elaborating on what we see. Not content to let others supply English subtitles, Godard has lately provided his own, or simply suppressed them during certain stretches of dialogue or voice-over.

One result of this obscurity is to redirect our attention. If we can’t comprehend the full story action, we focus on other things, such as the composition of the image, the interplay of sounds, the expressiveness of the music. Alternatively, the absence of clear-cut scenic structure throws an emphasis onto the texts that his characters obsessively read, cite, and recite. And when we do see clearly, there are the faces, given weight by the shots devoted to them (Notre musique, Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro).

There’s also the historical dimension of the deformations. A Picasso still life asks us to compare it to the classic exemplars of the genre. Similarly, Godard asks us to compare his forms and styles to their precedents. Détective, one of the few late films that hark back to classic Hollywood, proffers a mystery (who killed the Prince two years ago?), investigated by three characters. There’s also suspense, and a deadline for payment during a prizefight. Alongside this noirish premise is a Grand Hotel template juggling several couples and romantic triangles. But this “ensemble film,” packed with opaque shots and fragmented scenes, is far from the trim construction of classical Hollywood.

Similarly, Éloge de l’amour, with its quest to grasp the Holocaust, invites us into an art-cinema investigation plot reminiscent of L’Avventura. But instead of a search for a missing person, we get a dense adventure split into two parts (black and white film, trembling color video) that does what it can to cloud the inquiry, while bringing out a critique of Hollywood’s treatment of history.

“The best criticism of a film is another film.” Taking film history as a conversation among filmmakers, Godard bounces off Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero, Pialat’s Sous le soleil du Satan, and Truffaut’s Man Who Loved Women and Day for Night (below, with Passion).

Late Godard has shadowed Tati with distracting long-shot staging reminiscent of Play Time (here, Hélas pour moi) and has paid homage to him in Soigne ta droite.

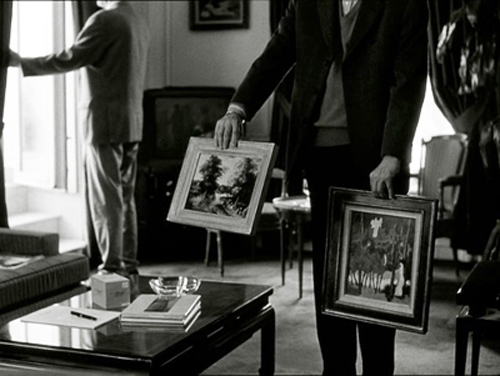

Even more pervasive is the invocation of Bresson. With a behavioral narrative, sound that replaces image, and the fragmentation of a scene through partial views, Godard seems to take a perverse “next step” beyond the master. Bresson died during the shooting of Éloge de l’amour, so there’s of course an homage, but more generally the late films’ style often radicalize Bresson’s technique, hands above all (Soigne ta droit, Détective).

Godard’s deformations not only “spoil” his own work but point to fresh possibilities in the traditions of narrative cinema.

Moments

Pierrot le fou (1965).

It’s not enough to note all the ways Godard impairs our comprehension of the story. As critics we need to show how the result can still add up to something coherent, even rigorous. We probably won’t be able to clarify everything, but we can try to show underlying patterns, in the way a critic can show a compositional logic underlying a cubist painting. I’ve tried to do this in two installments of our series on the Criterion Channel and in my analysis of Adieu au langage. Check the codicil to this entry for details.

But even if the overall strategy of disruption remains obscure, there’s a lot to engage us otherwise. Godard has given us scores of shots that no one had ever made before. Here are a few of my favorites, apart from ones I’ve already shown (Une femme mariée, Hail Mary, Made in USA, La Chinoise, Détective).

You have your own, I bet.

Given such shots, you can argue that the Godard narrative has been the bait to lure us into savoring privileged moments of cinema. Is this the heritage of Cahiers cinephilia–Godard’s version of “movie moments” that thrill us through what film (and video) can uniquely do? Or are they a refutation of the overblown CGI of Hollywood, showing what kinds of dazzling imagery can be achieved without special effects?

At any rate, such moments are especially resonant in the context of all the uncertainty. In all, we’re left with an aesthetic of exquisite spoilage. Godard teaches us to sense form underneath deformations, while still making imperfection a ripe artistic pleasure.

My references to Godard’s life are drawn from two excellent career accounts, Richard Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (Metropolitan, 2008) and Antoine de Baecque, Godard: Biographie (Grasset, 2010). Brody’s exemplifies what a true “critical biography” should be.

On the Criterion Current, David Hudson compiles links to several Godard tributes. Don’t miss David’s own discerning essay here.

For some years I’d thought of writing a little e-book on Godard, complete with clips. (Why not rip him off as he has done with so many others?) But as I’ve aged I recognized that I’m overmatched. Instead, some entries on this site approach him in bite-size chunks. This piece goes into some detail about his preference for the 4:3 ratio, and how video versions in wider format degrade his compositions. Thoughts about his use of Scope in Le Mépris are elaborated in my Criterion Channel installment of Observations on Film Art. Another Criterion Channel commentary considers the use of the classic ratio in Vivre sa vie. Quick remarks about Le petit soldat are here, based on a visit to Belgium’s Summer Film College. (Visit Cinéa and photogénie to survey the vast number of events and critical studies the College has fostered over the years.)

At another session of the College I offered some ideas about the late films, particularly Nouvelle Vague. (And when will a video version give us the proper 1.37 image for this film? Same goes for Sauve qui peut (la vie) and King Lear.) This entry looks at Godard’s use of Bressonian editing in Hail Mary. Kristin offers a contextual analysis of Film Socialisme, with close consideration of the controversial subtitles. Earlier she took it as an example of the sort of film arthouses should be committed to screening. My comments on that film are here. At the Vancouver film festival KT and I saw 3 x 3D and offered some comments. One entry on Adieu au langage traces some of his 3D tactics, while another considers this film in relation to other late features and offers a detailed analysis of the film’s opening. These essays were revised into the Kino Lorber DVD liner notes.

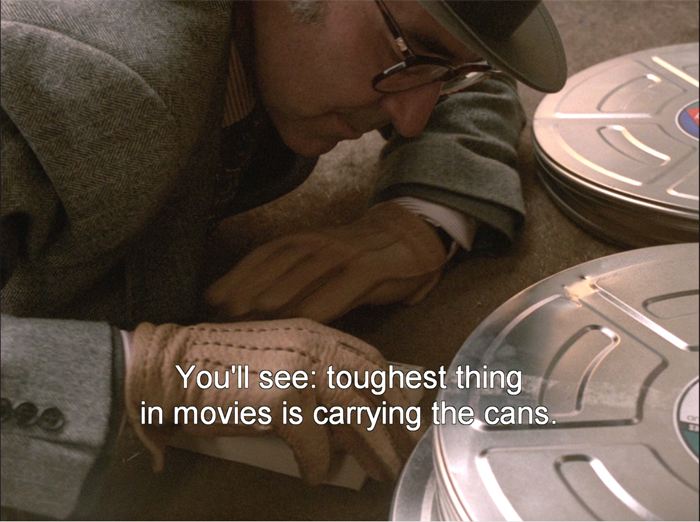

Soigne ta droit (1987).

Posted in Directors: Godard, Film technique, Narrative strategies |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Godard: The power of imperfection open printable version

| Comments Off on Godard: The power of imperfection

Monday | September 5, 2022

DB here:

In my early teens I bought murder mysteries from the legendary Claude Held of Buffalo. Lacking a checking account, I blithely sent through the mail dollar bills and even coins taped to the order. I still have S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen hardbacks from those days, but my most treasured item is a first edition of Howard Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (Appleton-Century, 1941).

Published on the hundredth anniversary of Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Haycraft’s survey of mystery fiction sought to establish the legitimacy of the genre. It became the authoritative source on the subject, and it’s still worth reading. Even then I had the habit of writing notes in the margins, and I’m ashamed of the jejeune scrawls that dare to call Haycraft to account. (“This is quite incorrect.”) Still, Haycraft confirmed my love of the subject and showed me what a serious literary history might look like. (Once more the adolescent window.)

Thirty years later came another powerful overview of the genre’s history. Julian Symons’ Bloody Murder aka Mortal Consequences (Harper & Row, 1972) was a revision and partial rejection of the standard story. Haycraft was a critic, but Symons, who reviewed mystery fiction, was also an accomplished novelist. The book is often harsh in its critical judgments, as when Symons downgrades Sayers as “pompous and boring” and classifies many of her peers as Humdrums. Symons promoted instead what he considered the strongest contemporary trend, the shift from puzzles to character-driven and socially critical writing. His subtitle sums up his argument: “From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel.”

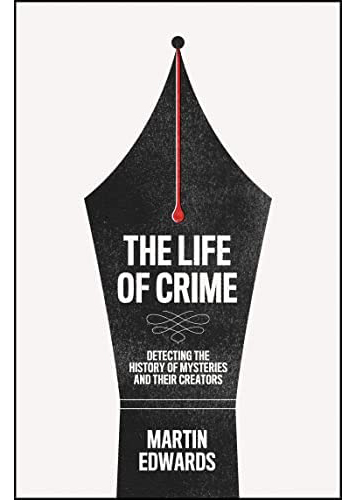

Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development. Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

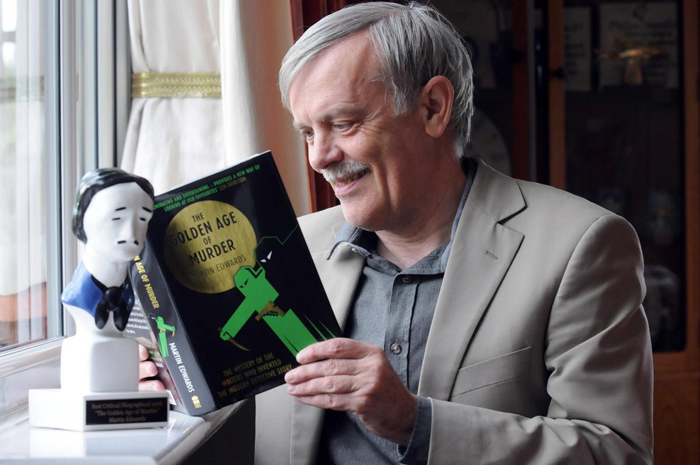

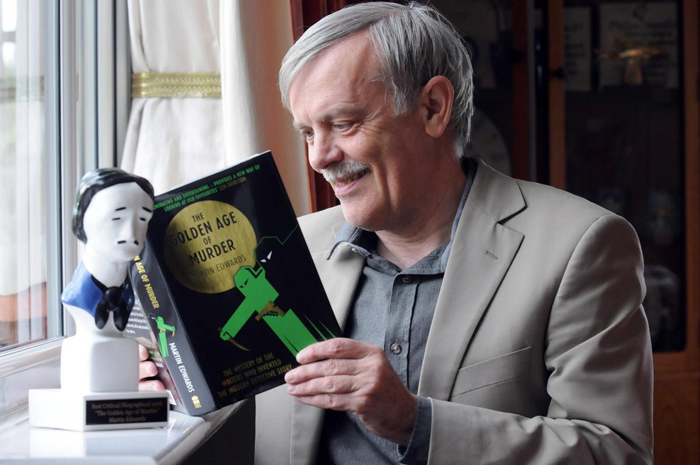

Martin Edwards’ Wikipedia entry makes your head swim: the man is a true polymath. Trained in the law and still a consulting solicitor, he’s a prolific, highly lauded mystery novelist as well. He has won virtually every literary prize in the field, not least the Diamond Dagger, the British Crime Writer’s Association highest award. His most recent novel, published on 1 September, is The Blackstone Fell.

Edwards is also recognized as the premiere historian of the genre in English, thanks to his many books, including The Golden Age of Murder (2016) and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books (2017). As if all this didn’t keep him busy enough, he writes a lively blog, “Do You Write Under Your Own Name? And he’s incapable of composing a graceless sentence.

So it’s no surprise that The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators is a monumental achievement. At 724 pages, resplendent with a burgandy string bookmark and beautiful colored end papers, it’s a triumph of modern publishing, and a stupendous bargain. (It’s currently going for $26.39 from the publisher.) The hardcover is currently ranked as #1 in Amazon’s Mystery and Detective Literary Criticism (with the audible book as #2).

The bulk and detail of The Life of Crime will incline many to treat it as a reference book. It functions superbly as that, thanks to a careful index, but it is even more. It provides a nuanced, reliable history of the genre; it offers rich insights into storytelling technique; and it teems with unforgettable stories of mystery authors. As the subtitle promises, it’s an account of both books and the people who create them.

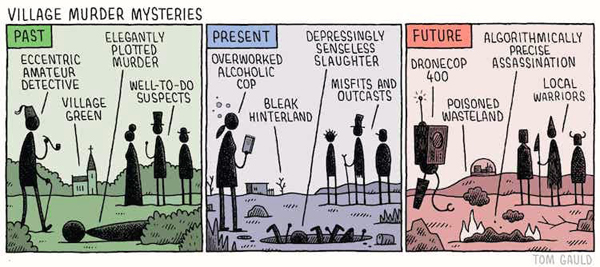

Crime waves

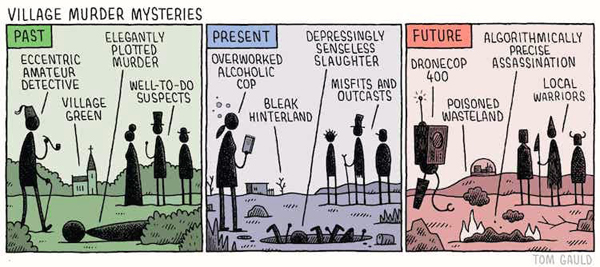

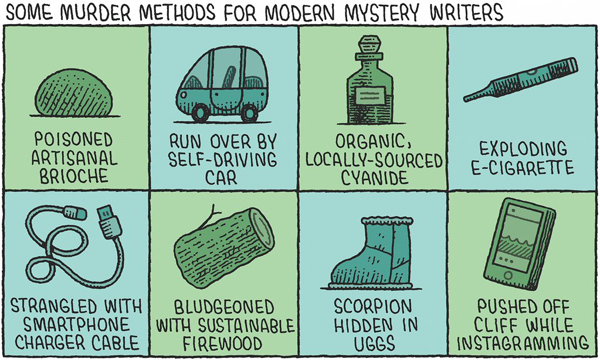

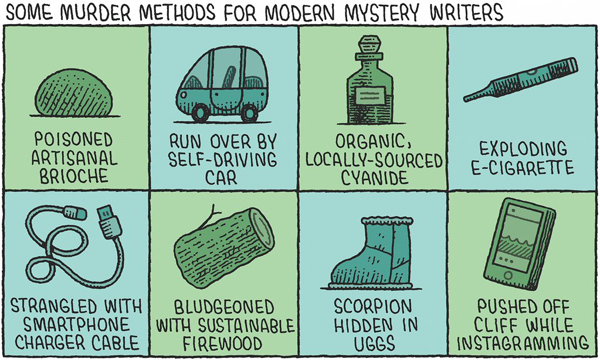

By Tom Gauld.

At the end of the 1930s, Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure could confidently sum up the standard trajectory. The detective story developed from Poe to Gaboriau to Conan Doyle, and then to the Golden Age of Christie, Sayers, Carr, Van Dine, Queen, and many others. Haycraft acknowledges the accomplishments of the 1920s British school, their US counterparts, and the emerging hardboiled trend typified by Dashiell Hammett. (Chandler was still a secondary figure when Haycraft was writing.)

Following the most self-conscious writers of the 1930s, Haycraft recognizes the need for the mystery to move closer to prestige fiction. He suggests it do so through a greater emphasis on characterization and on social commentary: the “novel of character” and the “novel of manners.” He sees the hardboiled trend as a variant of the novel of manners and warns that in its pure form it will soon wane. It “is beginning to become just a little tedious from too much repetition of its rather limited themes.”

Time would prove him wrong. The 1940s saw new variations in the hardboiled school, most evident in the spectacular popularity of Mickey Spillane. In Bloody Murder Symons faulted Haycraft’s analysis on other grounds. He failed to discern the growing power of the “crime story” as distinct from the detective tale. Thanks largely to Hammett, violence, eroticism, abnormal psychology, and official corruption moved to the center of writers’ concerns.

For Symons the apparatus of footprints, altered wills, and bodies in the library was surpassed by the rise of suspense fiction and the police procedural. Patricia Highsmith, Symons declared, is “the most important crime novelist at present in practice.” She, along with Margaret Millar, John Bingham, and Symons himself (!) typified the potential of the modern crime story, with Ross Macdonald revising the classic detective plot through the concern for “personal identity and the investigation of the past.”

Edwards holds Symons in high regard but has a more pluralistic conception of the genre’s history. The Life of Crime reaches back to the eighteenth century (William Godwin’s Caleb Williams) and ends with surveys of Nordic noir, East Asian detection, the contributions of contemporary women and minority writers, and the fashion for historical mysteries. The 55 chapters are organized around periods, trends, and exemplary figures. They survey not only crime literature, but plays, films, and television shows.

The broad picture Edwards paints shows how changes in the genre coincide with broader social dynamics. He’s especially good on the impact of World War I on an entire generation of writers and readers. Likewise, he traces how World War II spurred the rise of psychological thrillers in fiction and film, as well as the new platform of paperback originals.

Edwards’ comparative approach shows that the clash of Golden Age and hardboiled tendencies isn’t as drastic as Symons suggested. Symons saw Hammett and Chandler as in rebellion against the “rules” of the classic whodunit. Edwards shows that the hardboiled writers respected not only many Golden Age authors but also many of their conventions. For Edwards, the mystery tradition offers writers a range of creative choices not limited to a single notion of form or style.

An unabashed fan of Christie, Sayers, and their peers, Edwards is especially good at tracing the continuing influence of the Golden Age on contemporary work around the world. Who would have predicted the obsession of contemporary Japanese novelists with impossible crimes and narrative tricks, stemming from the canonical Edogawa Ranpo’s love of classic artifice? Popular examples are Shimada Soji’s Tokyo Zodiac Murders (1981) and Higashino Keigo’s The Devotion of Suspect X (2006). Edwards introduced me to a remarkable “book” by Awasaka Tsumao, The Living and the Dead, which, thanks to the Golden Age trick of sealed pages, contains a short story that disappears as you read the novel. The author, not coincidentally, is a magician.

One of the most striking assets of the book is the endnotes at the end of each chapter. Far from academic citations, these notes are often wide-roaming discussions of topics mentioned in the text. So, for instance, R. Austin Freeman’s worry that fingerprints could be fabricated gets this elaboration in an endnote:

Fingerprinting was used by Scotland Yard from 1901, but Sherlock Holmes examined for a thumbprint eleven years earlier, in The Sign of Four. In the US, fingerprint identification was central to the plot of Pudd’nhead Wilson, by Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens). But Freeman feared that reliance on uncorroborated fingerprint evidence could lead to miscarriages of justice. Hammett’s story “Slippery Fingers” reflects a similar concern, and some experts share it to this day (113, n8).

The dozens of reader-friendly endnotes offer a wealth of supplementary information, including recommendations for further reading. Any chapter’s supplements could provide scholars a host of leads for further research. These notes typify the generosity of the book, whose vastness conveys not pedantry but an eagerness to share information and excite the reader’s curiosity.

Edwards’ pluralism amounts to more than intellectual generosity. His book’s global sweep illustrates the astonishing fecundity of the genre in varying cultural contexts; it also shows how malleable its conventions are. I think he shows how fertile a tradition of popular storytelling can be–especially when it has the power to cross boundaries of time, place, and language. No reader of The Life of Crime can believe that this genre has run out of steam.

The toolbox

Tom Gauld, The Guardian (9 January 2016).

Most authors surveying the history of mystery discuss the narrative techniques employed by the various schools. Unlike most genres, mystery fiction’s identity depends on duplicitous manipulations of time, viewpoint, and narration. To conceal the crime and its perpetrator, the author must carefully select who knows what and when. The goal is to baffle both the investigators and the reader, with not only clues on the scene but also hints in the manner of telling. Needless to say, those clues and hints may be misleading.

Both Haycraft and Symons dutifully invoked the conventions of Golden Age bafflement. Haycraft treated them as the source of the genre’s distinctive pleasures, while Symons sometimes deplored their reliance on implausibility and coincidence. (He wasn’t, however, as demanding as Chandler, who famously remarked that “Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.”) As a writer sympathetic to Golden Age artifice, Edwards is eager to explore the whole range of devices available for mystery plotting. At this level, The Life of Crime is an encyclopedia of creative options available to the genre. Not surprisingly, Edwards’ wide compass shows that many “modern” techniques have distant historical precedents.

Aficionados recognize several ploys: false identity, faked death, slippery alibis, dying messages, equivocal clues, the absent clue (the dog that doesn’t bark in the night-time), the double bluff (X seems to have done it; wait, X is too obvious a suspect; nope, X actually did do it). Edwards goes beyond these to track how storytellers have used multiple narrators to cloud the situation and sharpen characterization. He shows the persisting power of the “inverted story,” the structure that shows the criminal committing the crime and then follows the detective’s exposure of guilt (the Columbo strategy). He devises a new term to accompany the “whodunnit” and the “howdunnit”: the whowasdunin, the plot that withholds the identity of the victim until the climax. This is a wider trend than I had realized. The same goes for the inclusion of letters and diaries in the text, which feels modern to us but actually goes back centuries.

And of course he doesn’t neglect reverse chronology, highlighted in one of those endnotes that can keep you busy for weeks:

This method of storytelling can dazzle, but only if the writers’ craftsmanship matches their courage. The possibilities are shown by Iain Pears’ novel Stone’s Fall, Jeffery Deaver’s The October List and Ragnar Jönasson’s Hulda Trilogy as well as by Simon Brett’s play Silhouette, Christopher Nolan’s film Memento, Harry and Jack Williams’ TV series Rellik, and Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith’s “Once Removed,” a witty and brilliantly economical episode of Inside No. 9 (612n19).

In all, Edwards’ sensitivity to innovations allows his book to be a stimulating source of craft practices to anyone who wants to write a mystery.

Mystery and misery

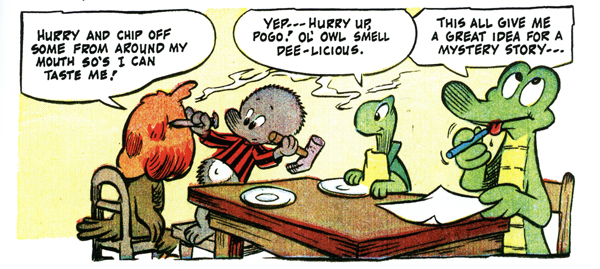

Walt Kelly, “The Big Comical Book Business” (Pogo Possum no. 5, 1951).

Sara Paretsky took up crime writing after contemplating poisoning her husband. Composer George Antheil, outraged by the attacks on his Ballet mécanique, wrote a novel in which barely disguised music critics were extravagantly murdered. Mary Roberts Rinehart refused to make one of her servants her butler, and he retaliated by trying to shoot and stab her. Patricia Highsmith smuggled her pet snails into England by hiding them in her bra, “six to ten per breast.”

At least as intriguing as the crimes in their books are the personal histories of the authors. Edward starts most chapters of The Life of Crime with an arresting account of one writer’s life. It’s often a catalogue of miseries. Alcohol damaged Poe, Hammett, Chandler, Highsmith, Craig Rice, Cornell Woolrich, and innumerable others. Drugs figured in the careers of Wilkie Collins (laudanum) and S. S. Van Dine (morphine). Suicide attempts and mental illness were distressingly common as well.

These usual artworld excesses are enhanced by mystery-mongers’ distinctive dose of weirdness. After a devastating traffic accident, Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gas Light, became obsessed with his brother Bruce. He refused to speak to Bruce’s wife and declared it was a pity that he, Patrick, wasn’t a woman; then he could have married Bruce. Bruce, a mystery writer himself, published a novel called A Case for Cain, in which one brother beats another to death with a golf club.

The juxtaposition of suffering and creative energy is marked. On the brink of financial ruin, morphine-addicted Willard Huntington Wright persuaded a distinguished publisher to issue three mystery novels under the pen name S. S. Van Dine. They sold in the millions and led to a long-running series. Rupert Croft-Cooke, after serving a prison term for homosexuality, fled England for Tangier and published dozens of detective novels under the name Leo Bruce. He also wrote twenty-seven volumes of autobiography called The Sensual World. Agatha Christie’s disappearance in 1926, probably due to temporary amnesia, was a response to her mother’s death and her husband’s infidelity. It didn’t hamper her immense productivity.

With his novelist’s eye, Edwards sympathizes with his subjects, but just reporting the facts still leaves you reeling. Of William Lindsay Gresham he records excessive drinking, occasional violence, and suicide attempts. When Nightmare Alley was bought for Hollywood, Gresham moved into a mansion. “He dabbled in folk-singing, and tried to ease his misery by exploring Dianetics, the precursor of Scientology, and taking an assortment of lovers. On one occasion he’d tried to hang himself on a hook, but it broke.” Years later, he killed himself with sleeping pills. “Legend has it that his pockets were stuffed with business cards bearing the inscription: No Address. No Phone. No Business. No Money. Retired.”

Edwards avoids sensationalism, but it’s good to remind us that much of the entertainment we enjoy was built on a lot of personal pain.

The Life of Crime is, then, a book in four dimensions: reference volume, historical survey, armory of literary techniques, and biographical accounts of major artists. To succeed with any one of these is remarkable; to succeed with all of them is something of a miracle. It will remain an indispensable guide to its subject.

Full, if belated disclosure: I read Martin’s book in manuscript and offered some comments, for which he kindly thanks me. He has also provided an endorsement of my forthcoming Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder.

The Life of Crime is already getting splendid reviews in the press and on the Net. There’s an illuminating interview with Edwards on the American Scholar podcast.

You’ll find plenty of funny cartoons on writing, including writing mysteries, from Tom Gauld here and here.

Martin Edwards. From the Warrington Guardian.

Posted in Film and other media, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book) |  open printable version

| Comments Off on A Monument to Mystery: Martin Edwards’ THE LIFE OF CRIME open printable version

| Comments Off on A Monument to Mystery: Martin Edwards’ THE LIFE OF CRIME

Tuesday | August 23, 2022

Heat (1995).

DB here:

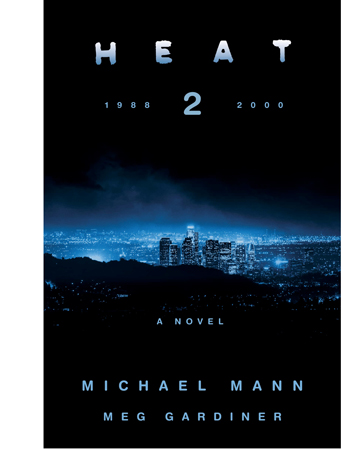

Last year, Quentin Tarantino wrote a novel that extended and reconsidered the story of Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019). Less elaborate is Michael Mann’s new bestseller Heat 2, written with Meg Gardiner. It’s not his first reworking of his film’s world: Heat (1995) was itself an expansion of a TV movie, LA Takedown (1989). Tarantino’s book was fairly experimental, as I tried to show, but Heat 2 is more conventional, being, as reviewers have mentioned, at once a sequel and a prequel to the original film. Yet it has its own interest, I think, and it provides me a chance to revisit a film I’ve long admired.

You’ve probably seen the film, but I’ll warn you of spoilers when I come to discuss the book.

Two genres for the price of one

In the film, Mann blends two schemas for crime plots: the heist film and the police procedural. What’s remarkable is the way both get expanded and interwoven to a degree rare in each of the genres.

The heist plot centers on Neil McCauley’s gang, consisting of Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer), Michael Ceritto (Tom Sizemore), and Trejo (Danny Trejo). The team members are married, and two have children. McCauley (Robert DeNiro) is a loner, living by the code that by being free of personal ties he can escape when the police close in.

In the course of the film, the gang plans three scores. The first, in the opening, is a robbery of an armored truck. Being short-handed, McCauley has had to add another team member, the sociopath Waingro, to consummate the heist. This robbery will reverberate through the film. Waingro shoots one of the truck drivers, forcing the gang to kill all of them. By seizing the bearer bonds of the money launderer Roger Van Zant and trying to sell them back to him, the gang sets off a cascade of broken deals and violent confrontations. McCauley fails to kill Waingro as punishment for damaging the heist, and Waingro emerges to help Van Zant stalk McCauley.

The second score, an effort to access precious metals, is aborted when McCauley realizes that the police are monitoring their preparations. The third score is a brutal bank robbery in which the team is virtually wiped out, with only McCauley and Chris surviving.

The heist plot adheres to many of the phases I’ve sketched in an earlier entry on the genre. The jobs are set up by the fence Nate and the computer whiz Kelso. The gang meets to plan each attack, with a division of labor among them. As often in the genre, the private lives of the robbers intervene. Chris, a gambling junkie, is in a fraught marriage with Charlene (Ashley Judd). Before the last score, McCauley advises Ceritto to walk away, since his wife Elaine takes good care of him. For the bank job McCauley recruits a prison pal Don Breedan (Dennis Hastert), whose wife Lilian (Kim Staunton) tries to sustain his effort to hold a job. And after Waingro kills Trejo’s wife Anna, the fatally wounded Trejo feels nothing left to live for. Most risky of all is McCauley’s growing love for Eady (Amy Brenneman), who makes him inclined to relinquish his solitude and unite with her after the bank job.

Braided with the heist plot is an investigation plot centering on homicide lieutenant Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino). He’s brought in through the armored-car murders and begins systematically to trace leads to the gang. In the usual procedural fashion, Hanna and his colleagues visit snitches, search records, tail and tape suspects, and gradually identify the gang. It’s their botched surveillance that induces McCauley to drop the second score. There emerges a game of tit-for-tat, as the gang in turn surveils the police and use their informants in the police to identify Hanna.

Police procedurals often fill out the action with scenes of the cops’ personal lives, and here that function is fulfilled by a portrait of Hanna’s failing marriage to Justine (Diane Venora) and his effort to nurture Lauren (Natalie Portman), their teenage daughter from another marriage. As the robberies test the family relations of the crooks, Hanna’s commitment to the investigation drives home to Justine his emotional distance and his refusal to open up to her about how he reacts to the crimes he encounters. Further intertwining the two plotlines, Hanna must also investigate the latest in a string of serial murders of prostitutes. We will learn that the killer is Waingro.

We might think of Hanna as the protagonist, with McCauley as the antagonist. But the weight given McCauley and his plotline inclines me to say that the film has two protagonists. Each is an antagonist to the other, with subsidiary antagonists (Waingro, Van Zant) adding pressure to the conflicts. Each man stands out, of course, by virtue of the presence of major stars. The performances are carefully calibrated. As McCauley, Robert DeNiro underplays to the point of paralysis: he acts mostly with the space between his hairline and his eyebrows.

By contrast, Al Pacio’s Hanna is full of swagger and bravado, using what Mann calls “manically extroverted” gestures and speech to intimidate others. But that’s on the job. At home, he’s taciturn, justifying his impassivity there as a way to preserve his angst and keep his edge for the street.

Mann’s screenplay teases us with brief confrontations between the two men. One takes place via surveillance video during the second score.

The most famous encounter is the celebrated diner scene, handled in protracted over-the-shoulder views. Here Hanna is much more subdued, modulating his eye movements to match McCauley’s constant scanning of the room.

The two plotlines culminate at the airport. McCauley interrupts his escape to kill Waingro and, reverting to his “discipline” of abandoning personal ties, must leave Eady alone. But he’s pursued by Hanna for a final shootout.

Apart from its binary-protagonist structure, the sweep of the film also makes it something of a network narrative. There are a great many characters and locales, and nearly every scene is elaborated in such physical detail that we have a wide-ranging survey of vivid personalities and situations. I haven’t mentioned the memorable informers whom Hanna interrogates, or Charlene’s louche lover Marciano, or Dr. Bob, the veterinarian who patches up the wounded Chris. Even the smallest roles (often played by recognizable actors) gain a memorable intensity. The breadth and depth of the story world suggests that the film might be a prototype for the “mosaic” structure of TV series like The Wire (20002-2008).

Work/ life imbalance

Narratives cohere largely through patterns of causality. One incident triggers another. But narratives also depend on parallelism–likenesses and difference among aspects of the story world. Parallels can draw comparisons among characters, locales, and situations. Michael Mann deliberately built Heat on parallels, as he points out in the 2005 DVD commentary track.

Most obvious is the comparison of Hanna and McCauley as men devoted to their work, at the expense of intimate relationships. (Parallels between cop and crook are virtually a convention of the policier.) Each man’s willed solitude is virtually a compulsion, and they recognize their affinity in the diner conversation. That is prepared for by almost telepathic reverse angles during the video surveillance, with the lighting’s angles presenting them as virtually split.

One benefit of the expansive plotting of the film is the way it creates parallels to other men. Nate, Kelso, and Van Zant seem as isolated as McCauley, though perhaps not out of principle. At the extreme is Waingro, also a loner, but one who preys on women–a psychopathic alternative to McCauley’s asceticism.

The film multiplies parallels among the couples. Ceritto has a warm relationship with his wife, and Trejo chooses death over life without Anna. Chris, for all his faults, is deeply in love with Charlene. Breedan responds resolutely to Lilian’s urging to reconcile himself to the unfairness of his new job.

Likewise, Hanna’s police colleagues are happily married. In parallel scenes, we see the gang and the squad enjoying lively restaurant dinners. Even Hanna unbends enough for a dance with Justine. Only McCauley, alone with the other couples, is marked as without a woman–a status that impels him to call Eady and invite himself over.

There are plenty of other parallels, not least that of vulnerable daughters, with the suicidal Lauren and the teenage hooker Waingro kills. But the ones I’ve just examined point up a common feature of classical Hollywoood plotting. Often American studio films interweave two lines of action, one based on work and another based on romantic love. Problems arise when the two can’t be reconciled. The husband may be consumed by pressures of the job, while the wife is neglected and her wishes dismissed.

More specifically, cop films and novels often play out the conflicting demands of duty (danger, disruption of routine) and love (of wife and children). This is exactly the life that McCauley foreswears and that Hanna tries to negotiate. The crux of the film is that both McCauley and Hanna entertain the possibility of a normal life only to find that their nature precludes it. Their counterparts seem to have managed it, but each gang member is also drawn to the adrenalin high of crime. “For me,” Ceritto says, “the action is the juice.” They all go along with the bank heist, with ruinous results. To a lesser degree, they are on the same spectrum as McCauley and Hanna.

The work/life tension is sometimes made apparent on the level of style. After Hanna dances playfully with Justine, Mann interrupts with the next scene, in which Hanna blocks the distraught mother from approaching her daughter’s corpse.

There is deeper concern, to the point of passion, in Hanna’s frantic embrace of this grieving stranger than in his flirtatious dance with his wife.

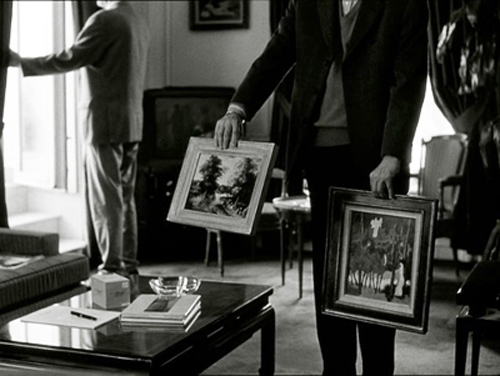

In such ways the film spares sympathy for the women. The plot brings out the parallel situations showing women beseeching the men to face their problems. Mann also uses visual motifs to heighten the comparisons. The women express themselves in shots of their hands. A bold composition in which Hanna blocks Justine heightens her gesture of annoyed resignation, and later close-ups show Charlene’s secret signal to Chris and Eady’s tension while waiting at the airport.

Men’s hands have other things to do, although one close-up of Neil fetching water for Eady suggests the man he might become.

The climax of this motif comes at the end, as Neil lies dying and Hanna accepts his handclasp.

Scrambled backstory

Now the spoilers for the novel commence.

In planning Heat 2 Mann and Gardiner faced some problems. At the end of the film several characters are dead, including the fascinatingly reticent Neil McCauley. To revive him, you have to create his backstory. Chris Shiherlis and his wife Charlene survive, but she has chosen not to give him to the police, so he will have to find a new way to live. And how will you treat Vincent Hanna–his past, his future?

The authors found several solutions, some of which vary Mann’s usual narrative strategies. The novel is broken into time periods, but not in the manner of the prototype for such sagas, Godfather II (1974). After a prologue sketching the action of the film, one section is devoted to the immediate aftermath of the bank robbery. This alternates Chris’s escape from LA and Hanna’s inability to track him. The authors found several solutions, some of which vary Mann’s usual narrative strategies. The novel is broken into time periods, but not in the manner of the prototype for such sagas, Godfather II (1974). After a prologue sketching the action of the film, one section is devoted to the immediate aftermath of the bank robbery. This alternates Chris’s escape from LA and Hanna’s inability to track him.

There follows a flashback to 1988, set mostly in Chicago, in which McCauley and his crew launch new heists. These scenes alternate with episodes of Hanna, stationed in Chicago, investigating some brutal home invasions. Eventually the gang executing the invasions learns of McCauley’s plans for a southwestern raid on drug smugglers and decides to rip off the team. The initiative is led by the monstrous Otis Wardell, a Waingro on steroids, who enjoys raping the women whose homes he invades. Ultimately Hanna’s frustration with his boss’s constraints on his investigation leads him to quit the force.

Most Mann films are resolutely linear in plotting. Apart from the time-jumping montage at the start of Ali (2001), he prefers chronological narrative. But now Heat 2 jumps ahead to 1995-1996. Chris has fled to Paraguay, where he takes up with a Taiwanese family involved in the arms trade and cybercrime. He falls in love with the chief’s daughter Ana, whom he helps gain power in the family.

The action returns to the southern border in 1988, with a showdown between Wardell and McCauley. In the course of a protracted firefight, Wardell kills Elisa Vasquez, the woman McCauley loves. Losing her is what plunges McCauley into the willed solitude that he projects in the film.

After another passage from 1996 bringing Chris and Ana up to date, the action jumps to 2000, after the events of the film. Everyone is now back in Los Angeles, and Hanna, remembering Wardell from his Chicago days, vows to capture him, while Chis vows to kill Hanna in revenge for McCauley’s death. Complicating things is the presence of Gabriela, Elisa’s daughter, who becomes a new target for Wardell. All these forces converge at a bloody climax.

Why did Mann break the prequel material into blocks and alternate the time periods? I suspect it was to maintain interest in the runup to the film’s action. If all the 1988 action preceded Chris’ 1990s career in Paraguay, we would have lost both McCauley and Hanna about a third of the way through the book. Chris would have had to carry a large central chunk of the story. Even as a soldier of fortune, he just isn’t as charismatic as Hanna and McCauley, so holding the resolution of the McCauley plotline in suspension keeps us turning the pages. Elisa’s death and McCauley’s devastation provides a strong lead-in to the film we have. Thereafter, the 2000 followup serves to wrap up nearly all the action. (The last line presents is a dangling cause that could lead to yet another sequel.)

The novel is less concerned with parallels than the film, although Ana’s frustration with the closed-in Chris matches that of Heat‘s wives. And Hanna’s fury at Wardell’s rape and beating of a teenage girl fuels his mission to find the gang, while thanks to a coincidence Wardell realizes that the waitress in a diner is the daughter of the woman he murdered in the desert. What knits the novel together most tightly is the premise that Hanna, McCauley, and Wardell were all in Chicago in the same years, but they were largely unaware of each other. We see links that the characters aren’t aware of.

This roaming-spotlight viewpoint is at work in the film as well, with the constant crosscutting of cops and crooks. But Mann and Gardiner take omniscience farther by penetrating the minds of the characters. Scene by scene we learn what the major characters are thinking, with some scenes containing several shifts of perspective. It would be as if the film gave us voice-overs from Hanna, McCauley, Chris, and others. The novel’s inner monologues remind me of Mann’s commentary track for Heat, which frequently draws larger conclusions and fills us in on what the characters are thinking. When Drucker pressures Charlene to give up Chris, Mann’s commentary reminds us that he’s trying to “build emotional solidarity” with her “despite having “a very short window.” Of Heat‘s two protagonists, he says:

These are the only two guys like each other in the universe. . . they are fully aware and conscious of who they are.

In the novel’s prologue the passage is:

Each navigated the future racing at him with eyes wide open. . . Polar opposites in some ways, they were the same in taking in how the world worked, devoid of illusions and self-deception.

The result is a narration that is, by the standards of Hammett or Elmore Leonard, over the top. On the same page, we get: “The detonation behind her eyes is seismic” and “For a second, she looks like she might explode.” Likewise, the perspective-shifting encourages scenes to be overelaborated; nothing is left to the imagination. But as with a lot of pulp writing, the novel has a raw power. We can treat it as a package, wrapping a Mann plot and dialogue in blunt, brash commentary.

Novel as script

A great deal of the appeal of a Michael Mann film is its richly textured surface. He is a “realistic” director insofar as he carefully researches a film’s milieu and takes pride in exact historical details. During a visit to Madison, he praised Dunkirk for Nolan’s attention to the Bakelite knobs on the aircraft. Yet Mann is also a pictorialist, always seeking striking, expressive shots that can de-realize the most familiar landscape, often through long lenses.

His early interest in video capture indicates both his realist impulse and his gift for abstract color design. Wanting to reveal LA at night in Collateral (2004), he wound up with night visions like nothing else on earth. Add in his talent for innovative film music. Heat‘s eclectic, melancholic score, so different from that of the routine action picture, is a big part of its power. So approximating a Michael Mann film on the printed page is far from easy.

Heat 2.0 tries. Written in the present tense, it has the staccato quality of a screenplay.

Gunfire. Deep. A rifle. Behind, them, rounds hit the connecting door from the far side. Somebody kicks it. Chris spins and fires a three-shot burst. They hear a body fall. More shots come through the wood, splintering it.

Reading it, you may find yourself hearing the dialogue in the voice of DeNiro or Pacino.

Ceritto glances around. The walls of boxes gleam in the spooky light. “Which one has the Holy Grail?”

Neil opens a gym bag. “Don’t matter. You find Jesus Christ, haul him out and hand him a sledgehammer.”

Hanna leans down into Alex’s face and grabs the crucifix in his right ear and rips it out through the lobe. Alex screams. Blood pours from the tear.

“Asshole!” Hanna shouts. “What the fuck do you think we’re gonna do? You are gonna flip, you dumb prick. You are gonna tell me everything I want to know, you cocksucker!”

He jerks Alex’s chin up, stares into his eyes, and shoves forward the cross. “The power of Christ commands you! I am your motherfucking exorcist. Tell me!”

Mann says he hopes to make a film of the novel. If he does, readers will hope that passages like these make their way into it.

Heat has proven to be an enduring modern classic. It’s encouraging that a followup to a movie nearly thirty years old can stir such widespread interest. Whatever happens to Heat 2, it shows that at age 79 Mann has not lost his lustre.

Nick James’s appreciative monograph on Heat offers many insights into the film. I discuss the heist genre and the police procedural in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots.

Heat (1995).

Posted in Film comments, Narrative strategies |  open printable version

| Comments Off on HEAT revisited open printable version

| Comments Off on HEAT revisited

|