Streaming media: All you can eat, until it eats you

Sunday | May 22, 2022DB here:

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas remarked: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

I wrote the preceding paragraph two years ago, and the Covid outbreak and enhanced technology have made the split between theatrical distribution and streaming distribution even sharper. (And as the Movie Brats predicted, multiplexes are raising ticket prices.) A crisis point was reached last month when Netflix glumly reported that instead of adding 2.5 million customers as it had expected, it lost some 200,000. Worse, the firm announced a likely loss of 2 million more in the next quarter. The news led Netflix stock to fall by over 30%, wiping out over $45 billion in value.

This stunning decline, coupled with Warner Bros. Discovery’s decision to cut the recently launched CNN+, sent shock waves through the industry. Stock values dropped for Disney, Warners, Paramount, and Roku as well, even though some had strong subscription growth. At the moment, disillusion seems to be settling in. A Wall Street analyst has noted:

We think the industry is facing a point of no return in which the economics of the old models look increasingly frail while the potential of the brave new world now appears overly hyped.

Discussions of mergers, acquisitions, and big company restructuring are ongoing, with layoffs already starting.

As researchers, we at The Blog try to see past current convulsions to larger patterns. But it seems plausible that we are approaching some significant changes. Without trying to predict much, and being no expert on streaming tech, I still thought I’d try to think through some ideas about the state of streaming and its historical significance.

An interim report

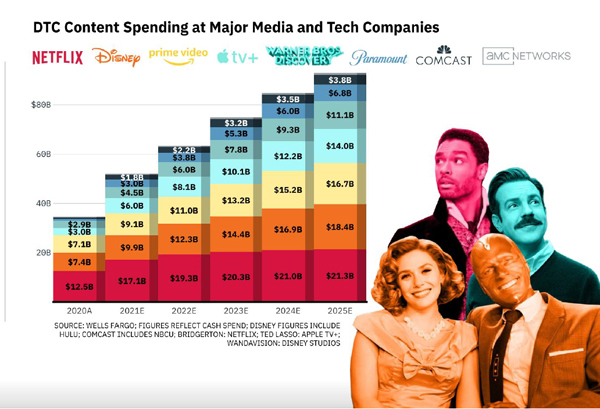

The Future of Content, Variety Intelligence Platform April 2022, p. 10.

Best to start with some basic information. Here’s what I came up with, all subject to correction and nuancing.

Streaming is now firmly established as a distribution/exhibition platform. It’s now the focus of all major US media conglomerates and it’s a market force every independent producer and company must reckon with. Broadcast television is waning. Viewership is declining, and this year saw a ten-year low in the number of pilot shows ordered by the networks. Cable subscriptions are likewise plummeting. Over the last ten years, cable channels lost 30-50% of viewers. Only the Discovery channel managed to grow, and live sports (e.g., ESPN) hung on, though damaged by the pandemic. Globally, streaming is growing rapidly, with both Hollywood majors and national and regional media firms plunging in.

Theatrical film, severely curtailed by the pandemic, is staggering. In nearly every country of the world, 2021 attendance was half or less that of 2017-2019. Studios are now releasing far fewer features, even in the crowded summer months. About 1000 theatre locations have not reopened since early 2020. Los Angeles has lost the Arclight and Pacific Theatres chains and the Landmark Pico theatre. In my home town a five-screen second-run house shuttered during the pandemic, and a six-screen multiplex is rumored to close soon.

As Lucas and Spielberg foresaw, the films that fill multiplexes are blockbuster franchises. So far this year, Spider-Man: No Way Home and Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness have done robust business, and exhibitors confidently expect big turnout for Top Gun: Maverick and Jurassic World Dominion. The surprise success of Everything Everywhere All at Once ($47 million box office) doesn’t mitigate the bleak prospects for most offbeat theatrical fare. Prestige films, romantic comedies, arthouse films, and many genre pictures can’t usually yield big enough returns, and the aftermarket–cable, DVD, and other ancillary outlets–which helped support them in the past scarcely survives.

Which leaves streaming as a primary source of filmed entertainment. At least 86% of US households access streaming services, either by subscription (SVOD) or as ad-supported services. The result is an immense amount of choice. You can browse studio libraries, imports, straight-to-streaming features (e.g., the latest Pixar releases) and series (e.g., Inventing Anna, Tokyo Vice).

Except for Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple+, the major streaming services are aligned with US entertainment conglomerates. Indeed, streaming made Netflix and Amazon entertainment behemoths, as attested by recent Academy Awards and Emmys.

Exact figures fluctuate, but the principal subscription streamers vary enormously in scale. At the beginning of this year, pre-meltdown, Netflix declared a global subscription base of about 220 million, with Disney+ at 196 million. Paramount claimed about 56 million (incuding Showtime and other offshoots), Discovery 22 million, and Peacock 24.5 million, including both paid and free. According to Amazon, over 200 million Prime members streamed material in 2021. As of March, Apple+ was estimated to have 25 million paid subscribers, with about twice that number benefiting from access via promotions (e.g., purchase of Apple hardware).

The simultaneous theatrical/streaming release (Dune, Wonder Woman 1984) is becoming rare as audiences return to theatres, but it remains an option (e.g., Firestarter). More common is a strategic delay far less than the usual ninety-day window that was common before the pandemic. The Batman opened in multiplexes on 4 March and was streaming 18 April. Universal and Paramount are prepared to send a feature online 17 days after theatrical release.

Fickle audiences and fluctuating “content” create churn. As a monthly subscription transaction, paid streaming lets consumers depart at will. Canceling cable subscriptions was difficult due to long-term contracts and obstreperous bureaucracy. Unsubscribing to Netflix or Apple+ is a lot easier. In addition, cable programming had a considerable stability, with long seasons and evergreen attractions. Studios signed extensive licenses for films and series, since cable was a perpetual money machine. Moreover, a movie might be available on several cable outlets. Now, however, the streaming industry faces audience churn.

Defections are common, especially among the young. An April survey found that nearly a third of Gen X subscribers and nearly half of Millennial and Gen Z subscribers have both added and dropped at least one streaming service in the last six months. Overall, nearly a third of subscribers say they have canceled at least one service in the same period. Web-experienced viewers are adept at hopping onto and off the latest thing.

Churn is accentuated by the exclusivity of the new media oligopoly. As the majors discovered the money to be made, they regained control of their library licenses. Netflix had The Office, its most popular attraction, until Warners took it back in 2019–soon after Netflix had renewed it for $100 million. The turnover is ongoing: this month Netflix lost Top Gun, the Ninja Turtles, the Muppets, Marvel TV series, and the first six seasons of Downton Abbey. The majors have gradually reasserted the exclusivity of their product.

As competition has intensified, streamers have been forced to acquire their own programming, both films and series. The pool must be refreshed to retain current subscribers and attract new ones. The problem is that once the new material has run its course, viewer loyalty can wane. This is especially true when the streamer dumps a full season of a series for bingeing: it encourages newcomers to sign up briefly and then defect. Disney has executed a powerful balancing act between legacy material and new offerings (Pixar features, Marvel spinoffs) that keep audiences faithful.

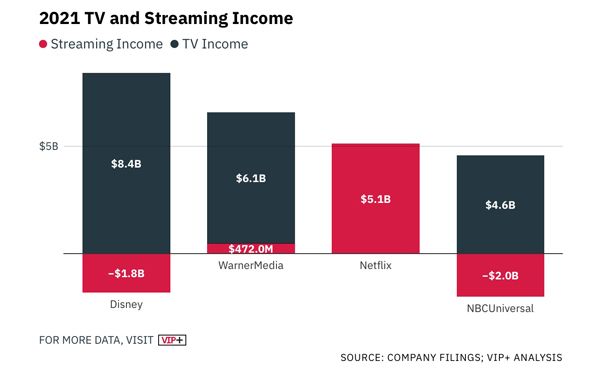

Streaming is not yet profitable. Broadcast and cable television are far more lucrative because they gain revenue from advertising and fees. Disney and Universal each lost about$2 billion on streaming in 2021.

Hence the concern over Netflix’s April report of decline in subscriptions. Streaming is its core business. A loss of $2 billion for the Disney conglomerate (parks, cruises, ABC TV, etc.) amounts to a rounding error. The majors’ deep pockets can sustain streaming enterprises for some time, but Netflix is far more vulnerable.

The streaming services are investing huge amounts in new “content.” The major providers are estimated to spend $50 billion acquiring projects this year. Producers are in a powerful position to demand big budgets to outmatch the competition. The costs are exacerbated by the high demands of talent, who now expect to be paid largely up front, since there is little opportunity for the deferred fees and back-end deals that depend on ancillary revenue.

No wonder then that several services have raised subscription rates. More drastically, in its current crisis Netflix has announced plans to offer an ad-supported tier of the sort already provided by Universal/NBC’s Peacock. Other services, Disney included, will probably shift to a similar option, especially since there is some evidence indicating that consumers will accept commercial interruptions in exchange for lower fees. Netflix also plans to control password-sharing, which helped it grow recognition but in the face of intense competition depletes its audience. It may be harder to combat the use of virtual private networks, aka VPNs, which allow roundabout access to region-based offerings.

One monetization strategy seems to be the rebirth of windows. Once a high-demand film is released to streaming, the service can add an upcharge for accessing it. Blockbusters like The Batman and the new Spider-Man trilogy were launched online with an extra fee for initial viewing. Over time, the prices fell gradually, just as in the old first-run/ second-run days. Even classics can benefit from premium treatment: The Godfather is free on Paramount+, but a rental costs $3.99 on Amazon Prime and Apple+. Arthouse fare is even more privileged; I paid $19.99 to see Drive My Car in its online release, though now it’s free on HBO Max.

It’s still TV

Bill Amend, Foxtrot.

In the late 2000s, streaming video entertainment was the province of mostly smallish, scattered companies like Twitch, Pluto, and others. Netflix and YouTube also took the plunge. Hulu, a consortium of Fox, Universal, and Disney, represented the majors’ initial effort to explore the market. As download speeds improved, problems with buffering and latency were overcome by new streaming protocols.

Soon enough, a familiar cycle emerged. Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch shows that mass information technologies (telegraph, telephone, film, TV) tend to consolidate into oligopolies. Major companies buy or kill off the competition. This happened with streaming, as one by one the big players came to the foreground. Netflix had early-mover’s advantage, having pioneered the distribution of DVDs by mail, and Amazon had a massive customer base in place already. The studios had helped Blockbuster wipe out small video-store chains, which had demonstrated the existence of a massive market, then turned their attention to selling discs directly to consumers. In 2019 the big players began to consolidate control over the expanding streaming landscape.

By acquiring other services (e.g., Paramount’s buying Pluto) and assembling proprietary components already in hand (e.g., WarnerMedia’s repurposing HBO Go), the firms have come up with integrated platforms. Disney+ launched in 2019, Peacock and HBO Max in 2020. Discovery+ and Paramount+ appeared in 2021, and Amazon bought MGM earlier this year. Sony, while licensing its film releases to its counterparts, has focused on animation by picking up Crunchyroll, which will absorb Sony’s Funimation service.

It’s early in the game, and it will take time for the companies to reassemble libraries that have licenses yet to expire. Doubtless many titles will be available for premium rental on rival sites, since no company wants to leave money on the table. Still, it seems clear that a considerable siloing of “content” will enable firms to enhance their power over their intellectual property. From this standpoint, we can think of streaming as a new phase in the development of home video.

In the earlier entry, I argued that home video formats gave the consumer a great deal of freedom. Even cable promoted “appointment viewing,” but tape, and then DVD, allowed the consumer a lot of flexibility. You could buy or rent a movie and watch it when you pleased. You could copy it too. Convenience is always a plus in a consumer item, and home video added to it a welcome price point: renting a tape or disc was cheaper than buying a movie admission, and in discount bins you could find a DVD for a few bucks.

With physical media, movies became manipulable by the audience. Ripping a DVD yielded a file that could be remade. Mashups, Gifs, and other transformations were feasible. Video essays changed film studies, and satire, homages, and fan analyses filled the internet. You could play with your movies.

Streaming withdrew this flexibility but offered greater convenience. A platform combines the array of a video store (think of those tiled pages as display racks) with push-button access. You still have the option of time-shifting, and you can share home viewing with others. But there’s no longer a physical medium. You don’t own or rent the film as object; you have bought access to it as a display, and only when you’re online. (“Buying” a digital copy is no guarantee of possession, if the service loses its license to the title.)

For decades, movie exhibition was a service business. We paid for the experience. Briefly, between 1980 and 2020, films became consumer artifacts as well. Ordinary folk enjoyed the sense of possession shared by film collectors of earlier decades. But with the decline of discs, we are once more paying for the experience while the object lies elsewhere.

Because of Hollywood’s preternatural fear of piracy, turning the artifact back into a service is a way to secure intellectual property. Not that people will stop trying to make personal copies. It’s possible to record streaming transmission, but the majors are counting on several factors. Just as people became tired of piling up DVDs they probably won’t watch, they could tire of filling hard drives with rips.

A few hardcore headbangers will enjoy sticking it to the man, but most people will reckon if you already pay for streaming the movie, why copy it? Given customer inertia and the convenience of streaming, why bother to pirate a movie that’s probably on streaming somewhere, available whenever you want? The trouble and expense of ripping may be greater than simply signing up for another subscription service. There are certainly overseas markets for pirated streaming shows, but as the companies expand their platforms abroad, piracy may diminish.

In sum, streaming has become the next step in the majors’ reassertion of control over their IP. It surpasses the old video store’s inventory, offers the convenience of click-ordering and time-shifting, and retains the advantages of in-home consumption. All we relinquish is ownership of a copy. Now that SVOD services are generating new attractions, providing long-running series with spaced-out hour-long episodes, and exploiting advertising-supported tiers, we are getting a version of fully on-demand cable TV.

We can glimpse this prospect in the demand for bundling, or aggregation. Customers’ biggest complaint is that there’s too much choice. The 200 channels of maximal cable are dwarfed by the streaming torrent. Nielsen estimates that as of last February there were 817,000 unique program titles available. Hence the emergence of streaming MVPDs, the “multichannel video programming distributors.” They provide a mix of movies, broadcast network series, classic TV, sports, and cable news. The best example is YouTube Live, which charges $64.99 per month, far beyond most of its SVOD competitors and reminiscent of classic cable fees. Yet YouTube Live is the most popular MVPD.

Add to this the number of FAST outlets, free ad-supported streamers such as Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Freevee, et al. With MVPDs these already constitute about a third of streaming offerings. One survey found that 34% of US consumers would prefer a free streaming service with 12 minutes of ads per hour. Streaming is starting to look like. . . well, just good old TV. The free platforms approximate broadcast TV, and the paid ones are cable reborn.

It takes time to make a classic

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill (2007).

Streaming demands a constant flow of new material, compared with the relative stability of broadcast TV, so the problem has been how to release it all. Netflix made a splash by dumping entire seasons at once, encouraging bingeing and getting immediate buzz and uptake. Viewers came to expect the big gulp. One survey found that over half of viewers under sixty now want firms to provide all the episodes of a series at once. But this strategy can damage long-term subscriptions by encouraging churn.

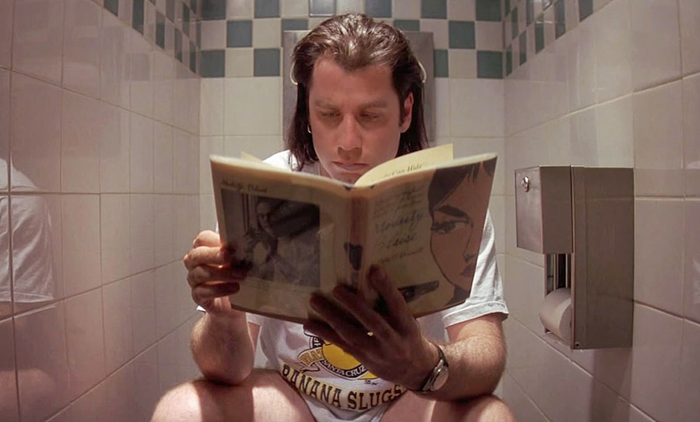

It also makes the product forgettable. Most direct-to-streaming films have a short shelf life. Does anybody watch War Machine (2017) or Bird Box (2018) now? Most auteur efforts seem to me to have had little cultural impact, not even Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019, with a mild theatrical release as well) or Soderbergh’s The Laundromat (2019). They came and went fairly quickly. A rolled-out theatrical film had an afterlife, it could circulate through the culture in many ways, and it could find niche audiences. Could The Godfather (1972) have its standing today if it were released straight to SVOD? Are there now “classic” streaming features?

This applies to art films too, I suspect. The international festival circuit allowed films to trickle from the big events to national and regional festivals over months, so outstanding films could build critical response and whet audience interest. Eventually some would find commercial distribution city by city. The pandemic compressed that process as festivals began to allow remote viewing of their screened titles, sometimes to audiences outside the locality. Kino Lorber’s Kino Marquee plan, which allowed simultaneous online access to new releases across the country, was a creative effort to maximize a film’s reach. Sponsored by local theatres, the plan in effect yielded a quick nationwide release on a scale that couldn’t easily be matched in pre-Covid days. It’s hard to imagine, though, that L’Avventura (1960) would have its standing today if it had played so quickly throughout the country.

Producers are belatedly realizing that the slow rollout characteristic of classic film distribution had the advantage of building audience awareness. A theatrical trailer is targeted toward habitual moviegoers and word of mouth. Theatrical releases garner promotion and extensive critical coverage that last longer than a Twitter alert. Theatrical screening can make a film an event–not always successfully, but at least it offers a chance. At a 19 May Cannes panel, a Swiss distributor pointed out that theatrical releases do better on streaming than straight-to-streaming ones.

The rationale is partly financial, of course. Here is the new head of Warner Bros. Discovery David Zaslav:

When you open a movie in the theaters, it has a whole stream of monetization. But more importantly, it’s marketed and builds a brand. And so when it does go to a streaming service, there is a view that that has a higher quality that benefits the streaming service.

There’s also the fact that a film on the big screen has a force that even a home theatre display can’t match. Another executive notes: “The undivided attention you get from an audience in a theater is where franchises are born.”

Classics, too. Even if most people see most films on monitors and personal screens, there need to be places for the proper display of them–living museums of cinema, in archives and cinémathèques but also in multiplexes and art houses. If streaming is making films ephemeral, we need to hang on to screening situations that let films claim our full engagement. If cinema becomes more like opera, as Lucas and Spielberg prophesied, let’s all become patrons and devotees, even snobs. Let films ripen over the years in a shared cultural space. Then we may get future masterpieces. Or so we might hope.

Thanks to Erik Gunneson, Peter Sengstock, and Jeff Smith for information and ideas.