M (1931)

Kristin here:

Our regular readers know that this annual series began as a simple salute to 1917, the year in which the basic norms of the classical Hollywood cinema definitively gelled. Starting in 2008, it became the “The 10 best films of …” list. It has stood in for the year-end ten-best lists which critics and reviewers feel obligated to concoct but which we avoid.

1931, I think, was a slight improvement on the rather lackluster 1930. A small handful of filmmakers mastered the “talkies” and made movies that look and sound as if they could have been made years later. These are the first four films below. It was a little harder to fill in the list beyond them. It’s is full of familiar classics, with a film or two that will probably unknown to many. I always try to include at least one worthy out-of-the-way title.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, and 1930

M

I remember seeing M as a grad student, or maybe even an undergraduate, and being horribly disappointed. This was a masterpiece? Actually it was only a semblance of one. In the 1970s a poor, incomplete 16mm print with as sparse a set of subtitles as I think I’ve ever seen was in circulation. The wit and brilliance of Fritz Lang’s sound links and voiceovers were largely lost, as were the sharp images now evident in the restored version. Even restored, as the introductory titles tell us, it is missing 212 meters. Fortunately that’s only .4% of the total, and the narrative progression is so smooth and absorbing that it’s hard to imagine that anything could be missing.

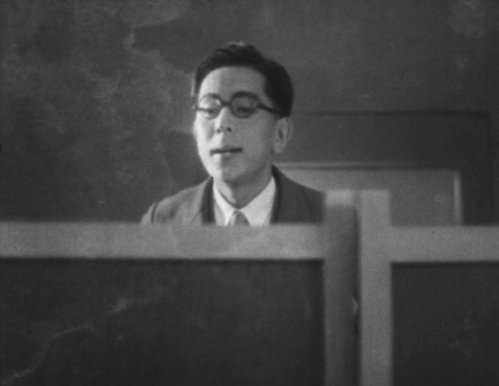

The story concerns a child-murderer terrorizing a city and the parallel searches for him by the police and by the organized underworld, the activities of which are being hindered by constant police searches and raids. At one point Lang famously intercuts a meeting of city officials with one of a group of gangsters. Parallels are created by matched gestures between space but also by one line being started by a character at one meeting and picked up by one at the other. Lang races through exposition by having the voiceover of a phone conversation between officials continuing over shots of the investigation in various spaces.

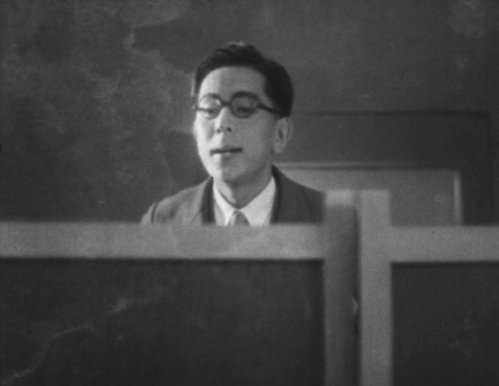

He uses sonic motifs as well. The killer compulsively whistled a Grieg tune as he lures his victims, but whistles come back time and again. Police whistles signal the raid on a basement tavern, and the beggars who tail their suspect signal each other with whistles–heard by the killer, who flees into an empty office building and ends up trapped there (top).

There’s a lot of offscreen sound in this film. The raid on the tavern cuts around to various parts of the space, as when we briefly follow a crook who tries to sneak out (above) while the protests of the crowd and the whistles and shouts of the police are heard off. One might think that all this is to avoid having to lip-sync the sound with the characters speaking–but when he does show the speaker, the sync is perfect. It’s another instance, I think, of Lang using sound to cram a lot of action or information into a short stretch of time. The thwarted crook is just a bit of comic relief, something Lang injects at intervals into this grim narrative.

Back in 2012, when I participated in Sight & Sound‘s poll of critics and academics for the ten best films of all time, I put M on the list. Counting 2021, it is the third film from that list that I have included in this one: The General in 2016, The Passion of Joan of Arc in 2018, and now M. The next one won’t show up for eight years (hint: Renoir made it in 1939), assuming I’m still doing this list at that point.

If you’ve never seen M, make sure you don’t watch an older print! The restored version is on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection in the US and Eureka! in the UK.

Le Million

René Clair made two film classics in 1931, À nous la liberté and Le Million. I find the latter a better film in that it’s more complex and lively. À nous la liberté, which focuses on only two characters who spend a stretch of the film apart, has a rather thin narrative. Le Million, on the other hand, involves a large cast of amusing characters and constantly bubbles with dances, chases, and farcical situations. Indeed, early on it cites the chase scenes of early cinema when police pursue the kindly thief, Père Tulip, over the rooftops.

The sets were created by the great French film designer, Lazare Meerson (who also did the more austere sets of À nous la liberté). The interiors often have soft, hazy backgrounds (top of this section) apparently done partly by painting and partly with real objects behind scrims. These give a stylized quality appropriate to a classic farce situation: the debt-ridden artist protagonist Michel frantically searches for a jacket holding a winning lottery ticket as the jacket goes from hand to hand. At one point crossing hallways permit two chases–the police after Tulip, the creditors after Michel–to pass through each other.

David and I taught Le Million in an introductory film class back in the 1970s. I hadn’t seen it since, but it lived up to my fond memories of it. As cheerful a film as one could find for what promises to be another year short on cheerfulness.

Le Million is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection. The description says that the lyrics are all translated here for the first time.

Arrowsmith

Early as it is, Arrowsmith is surely one of Fords’s great films of the 1930s. It’s an adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ 1925 novel of the same name. (Lewis won a Pulitzer for it but refused to accept the award.) The plot centers around Martin Arrowsmith (Ronald Colman), who starts as a medical student eager to establish a reputation and help discover cures for various plagues. He marries a charmingly impertinent nurse Leora (Helen Hayes), who supports him in his efforts.

The style of the film is distinctly flashy in its lighting, depth shots, and set design. It looks like what we tend to think of as Wellesian–though many of these techniques could instead by dubbed Fordian.

There are dramatic chiaroscuro effects as when Arrowsmith arrives home one evening, discouraged, and Leora sympathizes with him. The figures are side-lit with illumination coming from the kitchen, and Arrowsmith becomes a silhouette once he sits down.

The depth shots are equally impressive. A spectacular high angle (top of this section) shows three levels of a ship’s interior, with Sondelius, a medical expert, shouting up to the captain that he has discovered bubonic plague onboard. A less flashy but highly intense shot shows Leora’s death from bubonic plague. The long take is filmed with what David terms “aperture framing,” with Leora placed far off-center and relatively far from the camera, framed in the arms of the foreground rocking chair. It’s the same chair in which she sat when she smoked a cigarette contaminated with one of her husband’s plague samples. It’s a brilliant way to emphasize that she dies alone, with the bright open door at the center of converging lines of the set stressing that her husband does not suddenly appear, as we might expect, to comfort her.

Other more casual uses of depth with prominent foregrounds include a shot of Arrowsmith exiting his laboratory with beakers, bottles, and other equipment dwarfing him (below right).

Note also the prominent ceiling on the sets in the image on the left above. The notion that Citizen Kane was the first Hollywood film to use ceilings on sets has long been discredited, and here’s a good example of why. In general, Richard Day’s art direction combines with the cinematography to create powerful images, as in the hallway of the McGurk Institute, where Arrowsmith gains a research post.

We know that Welles was influenced by Ford’s work, but he primarily stresses Stagecoach as a film he watched repeatedly before making Citizen Kane. Arrowsmith, however, actually looks more like Kane than Stagecoach does. Did Welles and/or Gregg Toland see it? Very likely at least one of them did. There seems to be no record of Welles having said he saw it, but in 1938 he wrote and performed the title role in a radio version of Arrowsmith that had Hayes repeating her role as Leora.

Moreover, Arrowsmith was produced by Samuel Goldwyn. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Toland was making films there, including Eddie Cantor comedies (Whoopee!, 1930) and two crime dramas starring Colman (Bulldog Drummond, 1929, and Raffles, 1930). It seems implausible that he would not have seen Arrowsmith.

All this is not to say that Arrowsmith was the first film to play with depth and chiaroscuro. As David pointed out in a 2010 blog entry, such ideas were developing in Hollywood during the 1920s, and William Cameron Menzies in particular experimented with them. There David wrote, “The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment.” True enough, but I think Arrowsmith uses them more consistently.

So far Arrowsmith has not been released on Blu-ray, but the MGM DVD has surprisingly good visual quality for a film from this period. (Amazingly enough, you can still buy new VHS copies on Amazon.)

Kameradschaft

Like Clair, G. W. Pabst directed two classic films in 1931, Kameradschaft (“Comradeship”) and The Threepenny Opera. The former is a network narrative, cutting among several characters or small groups of characters as they react to a mine disaster.

The story is set in two villages on either side of a French-German border. Each is a mining town, exploiting what is actually the same rambling mine that has walls and bars in multiple tunnels marking the end of the German portion and the beginning of the French one. When escaping gas triggers a fire and ceiling collapses on the French side, two truckloads of German miners volunteer to go and help the rescue teams.

As the title suggests, the film stresses the theme of solidarity among the miners, though Pabst doesn’t paint an entirely rosy picture of this. The German miners coming off their shift argue about whether they should assist their French counterparts, and many declare that it’s none of their business. Pabst stages the debate in a visually interesting locale, the changing room where the mining outfits of the men are stored on ropes or wires up by the ceiling (above and below, left). The leader of the group which goes to help with the rescue is played by Ernst Busch, a well-known Communist actor-singer who was also in the original stage version of The Threepenny Opera and Pabst’s adaptation, as well as Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe (1932), from Brecht’s script. His presence as one of the main characters in the network plot–and the one who spurs others to volunteer as rescuers–helps give Kameradschaft a distinctly leftist tone.

As with many other films set in coal mines, the mine itself was an elaborate and convincing studio set (above right). One collapsing area of a mine looks much like another, but Pabst found ways to vary the action from scene to scene. Variety is added through a contrast in the main characters being followed. An old ex-miner sneaks into the mine to search for his grandson. Three German miners who didn’t go in the trucks to the French side decide to make a rescue effort on their own, breaking through the barred underground border to do so. They end up alongside the old miner and his grandson, trapped in the underground stable, where the presence of a placid but doomed horse adds a poignancy to the scene. At intervals the drama going on among the mothers, wives, and sweethearts of the French miners clustered at the gates is shown.

The weaving together of the various threads of action creates a strong sense of suspense. No one character can be singled out as the protagonist, the one who might be expected to survive. Some miners and rescuers escape, but there are many who die or suffer serious injuries.

Despite the emphasis on the comradeship of miner of both nationalities, the Germans definitely come off better. Their rescue team is well-equipped and efficient, while the French workers deal with problems like an elevator being out of commission. It probably would never have occurred to Pabst and the others involved to make a film where French miners help rescue German ones–and it probably would not have been greenlit by the production company if they had. On the level of the individual miners’ actions, however, the notion of working-class solidarity comes across.

Kameradschaft is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Tabu: A Story of the South Seas

Tabu was Murnau’s final film. (The opening scene of the hero fishing with his friends was shot by intended co-director Robert Flaherty, who soon quit due to disagreements with Murnau.) It deals with Matahi and Reri, who live a joyful life on unspoiled Bora Bora until an elderly man from a nearby island arrives and announces that the “Virgin sacred to our gods” has died, and Reri is to be her successor. Matahi rescues her, and the two flee to another island which has been colonized by the French. They have established a pearl fishery and hire local men to dive for pearls. Matahi proves expert at this, but not understanding what money is, he soon gets himself deep into debt by signing IOUs.

Rather than using Hollywood stars, Murnau cast local unprofessionals. As the credits announce, “only native-born South Sea islanders appear in this picture with a few half-castes and Chinese.”

The two leads are appealing characters, and the images take advantage of the unspoiled scenery of Bora Bora (below left). Floyd Crosby earned an Oscar for Tabu‘s cinematography.

Tabu is a far cry from Murnau’s German films, but Nosfertu‘s famous shot of the vampire’s ship sailing eerily into the frame from offscreen is echoed as a motif here (below right).

The original version released by Paramount was released on DVD by Milestone. A restoration of the original cut of the film is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Kino Classics in the US and Eureka! in the UK, both with numerous supplements. A helpful comparison of these versions is available here.

La Chienne

I think it is safe to say that most critics and historians consider La Chienne the film where Renoir’s distinctive traits as a director began to emerge. I have seen most of the early Renoirs, but long enough ago that I can’t make a comparison. It does seem to me, though, that it is quite different from his previous work.

Maurice Legrand, the protagonist played by Michel Simon, is the most Renoirian character. He is a mild-mannered accountant married to a termagant who nags him constantly and forces him to remove from their apartment the paintings and the equipment he uses for his hobby. This sets off the events which follow, as Legrand hangs the paintings in the apartment of a prostitute, Lulu, with whom he has fallen in love. Her pimp Dédé concocts a scheme to sell the paintings, which he passes off to a dealer as the product of an American painter named Clara Wood. Even when Lulu explains what happened to the paintings, Legrand is so besotted that he raises no objections.

Although “la chienne” of the title is clearly Lulu, it might refer to Adèle Legrand as well. “Chienne” is more-or-less the equivalent of the English “bitch,” meaning both a female dog and an obnoxious woman, which Adèle certainly is. In their first scene together, she berates Legrand at length, comparing him unfavorably with her first husband, whose portrait in military uniform looms over them (above). Legrand does not rebel but answers in quiet sarcastic comments and ultimately obeys her order about the paintings.

In French, “la chienne” has the additional meaning of a prostitute, clearly referring to Lulu. Legrand is trapped between a constantly angry wife and a prostitute skilled in behaving in a docile fashion, pretending, as she finally admits, to love him solely in order to maintain the flow of money from the paintings. This admission finally drives him to fight back, killing Lulu. He ends up as a jovial tramp, foreshadowing Simon’s later role as Boudu in what is arguably Renoir’s first true masterpiece.

Stylistically the film does not strongly resemble Renoir’s major films of the mid- to late 1930s. Still, the scene in which Dédé and his friend approach an art dealer in their first attempt to sell one of Legrand’s paintings consists of a longish take of nearly two minutes, with staging in depth (below) when the dealer returns from a search and a track-in to a closer framing for the negotiations. Also, the film starts as a puppet show, with puppets introducing the main characters, whose images are superimposed over the little stage (bottom). This looks far forward to his final film, The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir (1970).

La Chienne is available on Blu-ray and DVD from The Criterion Collection.

Tokyo Chorus

Last year Yasujiro Ozu made his first appearance on this list for That Night’s Wife. This year it’s Tokyo Chorus (or Chorus of Tokyo). With sound barely established in Japan, Ozu made this and several subsequent films silent.

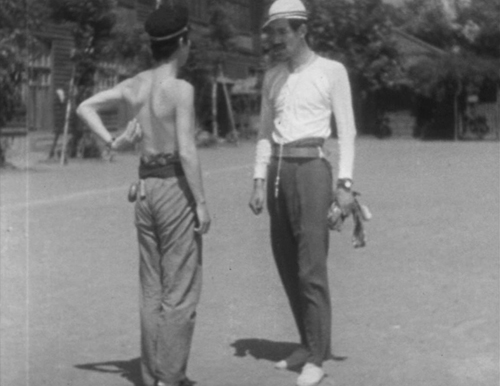

As the Criterion Collection liner notes explain, Tokyo Chorus combines the three genres Ozu had worked in before: the student comedy, the salaryman film, and the domestic drama. The student comedy subject gets disposed of early on, with the first scene showing the a comically strict teacher scrutinizing his class, lined up military-style; the protagonist, Shinji, tries some mild defiance by being late and showing off (below left).

Soon he has graduated, though, and is working in an office where the employees are awaiting their year-end bonuses. Just as quickly, Shinji is fired for protesting when an elderly colleague is fired just before his retirement and pension payments.

The rest of the film seems like a practice piece for I Was Born, But … (1932) and other Ozu films involving bratty kids who make demands on their parents. In this case Shinji’s son insists that his father buy him a bicycle and pesters him until he finally gets it (above right). As in the later film, Shinji is humiliated by having to take a job helping his old teacher to publicize his curry cafe.

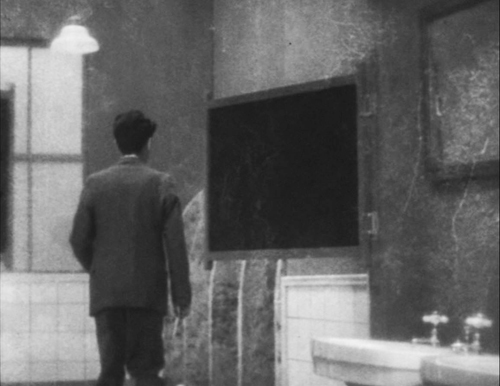

Ozu’s growing mastery of editing for comedy is shown off in the early scene when the office employees try to find out how big a bonus their colleagues have received. Shinji sneaks away to the restroom to open his envelope, pretending he has gone to use a urinal. A low-height shot shows another man coming in, with the swinging doors of the urinal area showing him only from the waist down. Shinji, just about to open his envelope, glances off and sees him. A reverse shot shows the colleague stopping and staring, clearly more interested in Shinji’s bonus than in using the urinals. Shinji gives up, pretends he is just there to relieve himself, and a final shot shows him departing still not knowing how big his bonus is.

By this point, Ozu has mastered balancing comedy and pathos, a mixture of tones that will reappear in many of his future masterpieces.

Tokyo Chorus is has been released on DVD, appropriately enough along with two of those future masterpieces, I Was Born, But … and Passing Fancy (1933), by The Criterion Collection.

City Lights

I must admit that I do not admire City Lights as much as The Gold Rush and The Circus, which featured in my ten-best lists of 1925 and 1928. I think it has some narrative problems.

For one thing, the blind flower seller as a love interest is pretty passive and doesn’t allow many opportunities for generating humor. In The Gold Rush, Chaplin had the inspiration to introduce a dream sequence about the dance-hall girls, including his beloved Georgia, coming to dinner with him. He then inserted his classic gag, the dance of the rolls. Much of the action in The Circus involves the heroine, as with the magic act into which the Tramp stumbles. The flower seller mainly generates pathos, right up to the ambiguous ending. (I have seen commentators take the ending as a clear indication of a budding romance between the pair, but I think we get no clear indication that her gratitude for the help the Tramp has provided will blossom into love.)

Chaplin needed to fill out the film with action beyond the few scenes involving the flower seller. Much of the action involves the Tramp’s on-again, off-again friendship with the eccentric millionaire, which is a weak premise to carry so much of the narrative. This character treats the Tramp as his closest buddy when drunk but then fails to recognize him when sober. This happens three separate times and gets a bit repetitious in a way not seen in other Chaplin films. The main contributions of the millionaire to the plot are to give the flower seller the impression that the Tramp who buys her flowers is a wealthy man and to give the Tramp the money for the flower seller’s eye-restoring treatment. The character of the millionaire does create some humorous bits, as when the pair eat spaghetti and the Tramp gets a curly streamer mixed in with his and keeps on eating it. I can’t help contrasting the millionaire with the Mack Swain character in The Gold Rush, whose interactions with the Tramp generate so many hilarious gags.

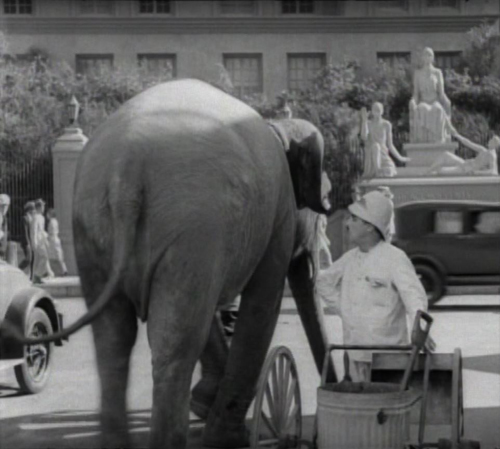

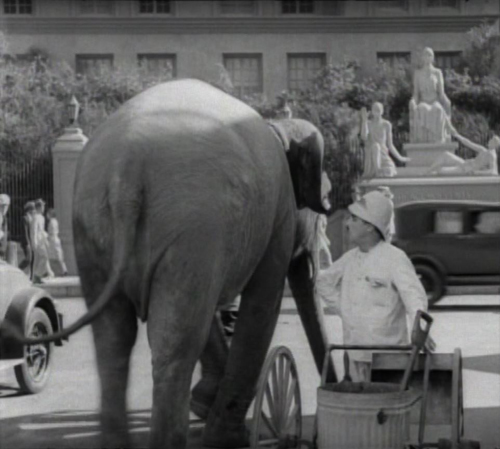

There are admittedly other funny scenes, especially early on, when the Tramp is discovered asleep on the lap of a statue being unveiled before a crowd or when he becomes a street cleaner to earn money for the flower seller and is immediately confronted with a group of horses and, as a topper, an elephant passes.

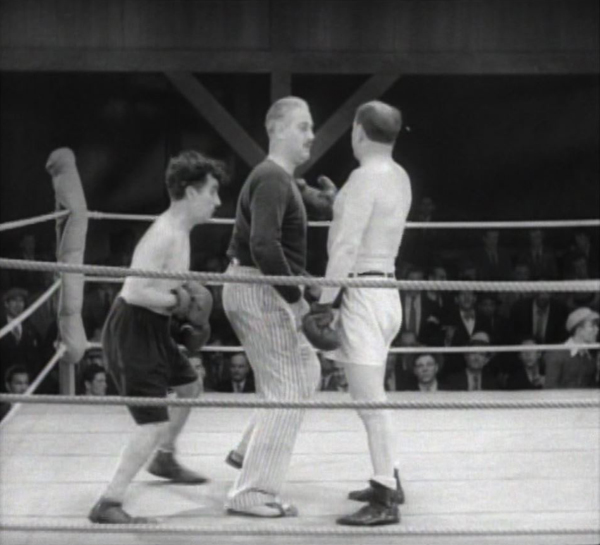

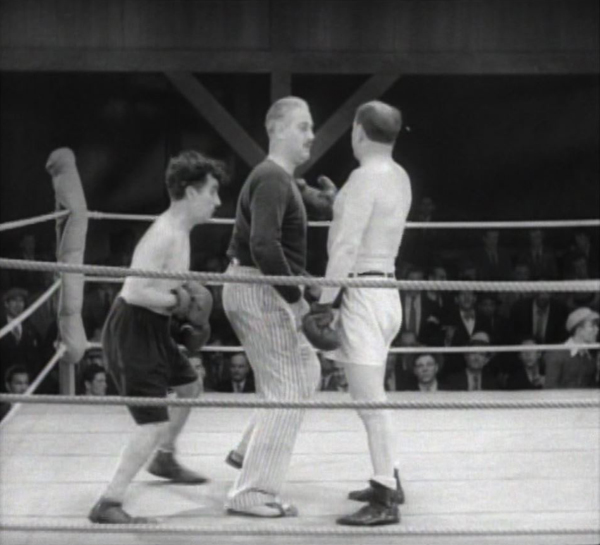

Later on in the film, though, the plot premise of earning money to help the flower seller have an operation to restore her sight generates one of the funniest scenes in all of Chaplin’s work. He agrees to participate in a fixed boxing match, with his opponent going easy on him and the two splitting the purse. The opponent is replaced by a tough guy who clearly has no intention of playing nice. The Tramp’s tactics to avoid being beaten up involve dancing around directly behind the referee at first (top of this section) and then, in a dazzling bit of choreography, the three figures move around the ring, changing places repeatedly so that the Tramp is sometimes behind the referee, sometimes behind his opponent, and so on. It is reminiscent of the scenes in the hall of mirrors as the Tramp is chased by a pickpocket and then by a policeman in The Circus, with the characters and their reflections dodging in and out of view.

Chaplin famously refused to allow spoken dialogue in his film, despite the fact that the transition to sound was well established in the USA by 1931. He restricted the track to music and sound effects, a tactic he carried over to Modern Times as late as 1936, though there the Tramp’s voice is heard for the first and last time singing a nonsense song. Chaplin retired his long-time character thereafter.

City Lights is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Odna (Alone)

When I was in graduate school, the only film by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg widely known outside the Soviet Union was their 1926 adaptation of The Cloak, which appeared in my best-ten list for that year. Then people discovered, to some extent, The New Babylon, which appeared in the entry for 1929. I suspect that few people have seen, or even heard of, their marvelous first sound film, Odna.

It was planned as a silent film, but delays permitted the use of sound technology to add a track to it. The main element of the track is Dimitri Shostakovich’s musical accompaniment. (He had also composed the musical accompaniment for The New Babylon.) The music comments on the action, often in a mocking way. Occasionally there are sound effects, and very occasionally, brief lines of dialogue, recorded and added after the filming.

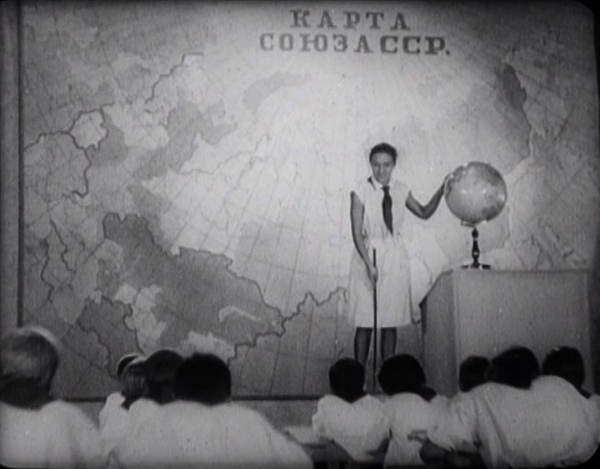

The plot centers around a young teacher fresh out of school, Yelena Kuzmina (played by Yelena Kuzmina, who also played the protagonist of The New Babylon).

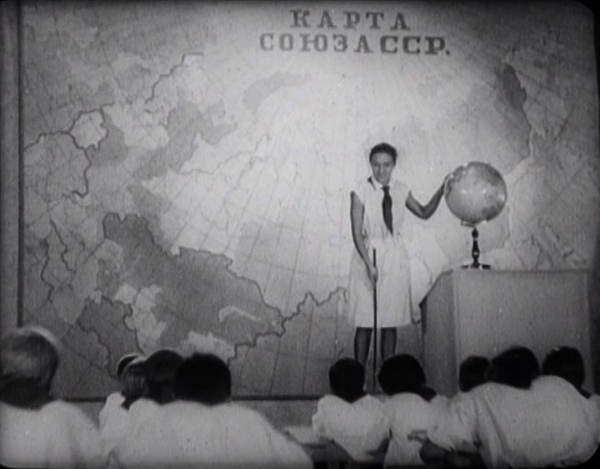

The first section of the film is played with an absurdly jolly exuberance. Yelena is engaged to a handsome young man, and a lively montage of shots shows her visions of the ideal life she plans to lead with him in Moscow, including window-shopping for expensive sets of dinner crockery, playing a musical duet at a cafe (below left), and teaching attentive children seated in neat rows in a well-equipped classroom (top of section). Shostakovich’s music is ridiculously cheerful, and a song about how beautiful life will be plays over a shot of Kuzmina’s fatuous grin (below right).

The tone switches abruptly as Kuzmina receives an assignment to a teaching post in a remote, mountainous primitive district of Siberia.

Devastated, she lodges a complaint, which seems likely to succeed. An elderly man in the office tells her that she’s right to try to change her assignment (below left). She erupts, “I’m going anyway!” This is one of the few post-dubbed lines.

Upon arrival in the Siberian district, she encounters a dead horse’s skin on display (below right); this returns as a motif to emphasize how primitive and in need of education the area is. At first the villagers react with indifference or antagonism, seeing no point in having their children go to school. Oddly enough, the local Soviet official is lazy and also indifferent, leaving her alone with no aid in convincing the villagers to accept her. (This negative depiction of the Soviet official later got the film banned, despite its considerable popularity upon its initial release.)

Apart from encouraging teachers to accept whatever school they were assigned to, the film has the anti-Kulak theme that was common in Soviet films about the countryside. (See the discussion of Eisenstein’s The General Line in the 1929 entry.) A wealthy local landowner has secretly sold off the sheep that technically belong in common to the villagers, whose main source of income is the wool. Kuzmina exposes the theft and helps the local people resist it, thus finally gaining their trust.

The next-to-last reel of the film, in which the landowner tries to kill Kuzmina, is missing. A restored version of the film accompanied by a reconstruction of the Shostakovich score was released on Dutch and German DVDs in 2007. (The frames here are from the Dutch DVD.) It includes a long series of intertitles describing action in the missing reel, drawn-out so as to match the length of the music, which does survive. As far as I can tell, these DVDs are no longer available. I am reluctant to recommend a version on YouTube, derived from the German DVD and superimposing English subtitles on German ones, on top of Russian intertitles. It does seem to be the only widely available way to see the film at this point, so for those who can put up with the clutter and the poor quality of the online version, it is here. A complete recording of the charming music is still available.

La Petite Lise (1930)

My tenth film is a holdover from last year. I consider Jean Grémillon’s La petite Lise a film worthy of the top-ten list, but when compiling last year’s list I somehow misremembered it as being from 1931. It just goes to show that one should double-check on such things.

Decades ago, I first saw La petite Lise in a 35mm print on an editing table at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). I finally saw it on the big screen in 2015, when our UW Cinematheque ran a few Grémillon films in 35mm. Then-graduate student Jonah Horwitz provided the program notes.

Grémillon is best known outside France for the trio of films he made during World War II: Remorques (1941), Lumière d’été (1943), and La ciel est à vous (1944). Criterion has released a box set of all three as Jean Grémillon During the Occupation. Some of his other films are available on disc, as a search of the director’s name on Amazon.com or amazon.fr reveals (including some with English subtitles).

The simple plot involves Berthier, who is serving a long sentence in a prison in Cayenne for having killed his wife in a fit of jealousy. Heroic behavior on his part during a recent fire has led to an early release, and he expresses his desire to see his daughter, Lise, now grown up. All this sets us up to be sympathetic toward him, despite the fact that he is played by by Pierre Alcover, a large, rather sinister looking actor. (Best known to modern audiences, I suppose, as the corrupt banker in L’Herbier’s L’Argent.) Unbeknown to him, Lise has been working as a prostitute but has now ended that in anticipation of marrying André. The pair are in desperate need of obtaining 3,000 F within 48 hours to buy a small house.

Berthier’s reunion with Lise is joyful, and he manages to find a job with his old boss, who gives him a generous advance on his salary. Knowing nothing of this, Lise and André visit a Jewish pawnbroker who André believes has cheated him in the past. When he threatens the pawnbroker, a fight breaks out, and Lise accidentally kills the man. Berthier learns of her past and of the killing, and his great love for her leads him to turn himself in as the killer.

The story is quite touching, in large part because Alcover and Nadia Sibirskaïa (who played the younger girl in Menilmontant) convey the deep love between the pair.

Grémillon adds some unconventional touches which have little direct relation to the plot and are largely dependent on sound. These give the simple plot some variety.

The opening, for example, takes place in the Cayenne prison, with Berthier learning of his pardon from the warden. In the crowded dorm, he reveals to two fellow convicts that his good fortune makes it impossible for him to participate in a planned escape. He shows them a photograph of Lise as a child. Most of the extended dorm scene, however, consists of fairly tight shots of other men’s activities, all packed into the crowded room. The soundtrack, rather than catching scraps of dialogue, remains a loud babble of many men talking at once. These shots tell us us next to nothing about the narrative, beyond suggesting the grim conditions to which Berthier faces returning to at the end. It does, however, create an effective atmosphere of the prison as a backdrop to occasional shots of Berthier gazing at the photo of Lise.

Another example is a scene late in the film, when, having learned of the killing, Berthier goes looking for André. He tries to enter a nightclub, but it is too crowded. He stands watching with several others through the window as a Black dancer performs a lively number for a mixed Black and white audience. For a brief interval, the scene becomes a musical number, extending to the point where couples start dancing, with Berthier becoming quite peripheral to the action. The performer and dancers add nothing to the story, but the scene is delightful in itself.

These and other moments draw us away from the linear progression of the story and make La petite Lise one of those small, simple films that transcend their apparently modest nature–like those of Jean Epstein and Dimitri Kirsanoff.

La petite Lise remains difficult to see. It has never, as far as I know, been available on home video. Grémillon’s film is not on YouTube, but there are several clips from key scenes. (All are pretty poor in quality, and I haven’t seen a good print of it. If elements survive in archive, it seems a major candidate for restoration.) An excerpt from the scene in the prisoners’ dorm near the beginning gives a good sense of the babble of voices. The Black dancer’s number as Berthier searches for André is shown nearly in its entirety. Both of these were put up at the time of the Cinematheque screening in Madison. There are some other brief scenes: the visit to the pawnbroker leading up to the murder, the scene of Berthier applying to his former boss for a job (which includes a sound bridge from the previous scene of Lise at home), and the scene in a restaurant which Lise and André visit in the hope of establishing an alibi. Otherwise, keep an eye open for it if you live near at archive that has public screenings.

For a look at Ford’s flashy style in his earliest features, see here. For a defense of How Green Was My Valley‘s Oscar win over Citizen Kane for best picture, see here.

My video essay, “Mastering a New Medium: Sound in M“ is number 11 in the series “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel.

La Chienne (1931)