Wednesday | May 19, 2021

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020).

Kristin here:

Last time I wrote about three Middle Eastern films. Now I’m writing about three films that are all over the map and presented in no particular order. Such are the pleasures of film festivals, including the Wisconsin Film Festival, which wraps up Thursday, May 20. At 11:59 pm, all the films will be taken offline and we can all look forward to next year’s festival–with luck, back on the big screens of Madison.

The Village House (2019, India)

Achal Mishra’s first feature is a slow, entrancing, nostalgic love letter to his parents’ sprawling villa. The film is broken into three parts, set in 1998, 2010, and 2019. There is no real storyline, apart from the inevitable dissolution of the large extended family that inhabits the house in the first part. There is little dramatic conflict, either. Instead Mishra films everyday activities: men playing card games and teasing each other, women perpetually cooking or caring for a new baby, boys lured away from a game of hide-and-seek to go pick mangoes. It’s the sort of ideal of capturing the quiet poetry of life that the Neorealists never quite achieved.

Mishra admits to being strongly influenced by Ozu and Hou Hsiao-hsien (in his podcast discussion with programmer Jim Healy), and it shows, though there is never overt imitation. The camera never moves, and there are nearly as many shots of empty locales as those with people present. Idle conversations are lingered over in long takes.

Mishra also mentions Wes Anderson, and there certainly are quite a few planimetric shots in the film (above). The three time periods are also set off from each other by different aspect ratios: nearly square for 1998 (also above), widescreen for 2010 (second frame below), and full anamorphic widescreen for 2019. The purpose of these contrasting framings are quite different from Anderson’s in The Grand Budapest Hotel, where the the shots imitate the film ratios of the historic periods that the story moves among.

The narrow rectangle of the 1998 scenes suggests the crowded bustle of the house. From side to side it’s full of food (yet again above) and people in many shots.

We don’t get much of a sense of the geography of the house, just that it’s full of rooms where ordinary things are going on. We also probably have some trouble figuring out who all the characters are (especially since the jumps forward in time have different people playing them). Still, there’s always something to look at and listen to.

By 2010, the house is aging and the village offers fewer opportunities. One of the sons can’t find a job and wants to sell a plot of land to get money to start a pharmacy. Perhaps the biggest drama in the film comes when an older man tries to talk him out of it. The mundane is still present, though, as one brief scene consists of one character telling another, “The toilet door needs repair, and the kitchen door is jammed.” This casual-sounded remark turns out to be a hint of things to come.

The village still offers traditional festivals, but the sense of community has become less idyllic.

Slowly, however, the family members leave, culminating in the wordless departure of the old grandmother at the end of the 2010 scene.

The final third opens into full widescreen, with more extensive views of the house, empty or nearly so. These don’t give us a much better sense of its geography, but definitely a sense of its desertion by all by an elderly caretaker and some intrusive goats.

The renovation of the house starts at this point, though we are not shown what it eventually came to look like.

The Village House is available to stream anywhere in the USA until the end of the festival.

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020, France)

Rémi Chayé’s film won the Cristal for a Feature Film (top feature) at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival for 2020, and it’s easy to see why. Done with hand-drawn images, it has a look all its own. The unblended areas of color create a simple but beautiful set of images (top and above).

The story is aimed primarily at children. It tells an imagined tale of the childhood of Calamity Jane (about which very little biographical information survives), who gains skills and self-confidence when her widowed father is injured during a wagon-train journey west. It’s a woke story for the modern age, as young Marsha endures bullying from the guide’s son and ridicule over her tomboyish clothes and behavior.

Some of her achievements are bit over-the-top, but there’s a tall-tale aspect to the narrative–as is emphasized by scenes in which characters boast of their own acts of bravery around the campfire. It’s entertaining enough, but adults will probably be more impressed by the visuals.

The film is in French with subtitles. I would say that any child not old enough to read subtitles would probably be scared by some of the bullying, violence, and near disasters that occur, though older kids could probably handle them pretty well, given that all ends happily.

Calamity is also available nationwide for the duration of the festival.

Fear (2020, Bulgaria)

I went into Ivaylo Hristov’s Fear knowing little about it except that it deals with a middle-aged Bulgarian widow who captures a lone African refugee. At first she is afraid and suspicious of him but gradually, of course, comes to feel sympathy and even friendship for him. Something of a cliché in this day and age, I thought.

It turned out to be far more complex than a warmhearted tale of a bigot changing her ways. For a start, it’s a throwback to the more cynical of the black comedies of the Czech New Wave, with a similar kind of humor directed against the local authorities, primarily the border patrol and the mayor. They are required by law to feed and house refugees coming across the border before sending them onto the next facility. Most people crossing the Bulgarian border are on their way to Germany. Bamba, whose family have been killed in an unnamed African country, is going there, as are a small, hapless group of Afghans rounded up by the border patrol.

That patrol is mocked, as in the absurd line-up by height in the image at the bottom. They are completely unprepared to accommodate the Afghans, herding them first into the closed local school and later into the open-sided apartments in an abandoned construction site. These are not, however, the bumbling but largely harmless officers of The Firemen’s Ball. Underneath the gags, they are racist, ignorant bullies, roughing up the completely passive Afghans during the round-up. A chillingly funny interview of the officer in charge by a local TV reporter goes on in the foreground, with her repeatedly asking if the Afghans are armed and violent. When he replies that he’s never caught one with weapons or met any resistance, she begs for an anecdote of a time when the patrol was threatened. Again he says there wasn’t one, and she turns to the camera, triumphantly announcing that her audience has witnessed the dangers of letting refugees across the border.

The main story starts quietly by characterizing our heroine, Svetlana, as fearful. She has just lost her teaching job, and we learn that she goes regularly to the cemetery to talk with her dead husband. She lives alone in the country and sleeps with a hunting knife under her pillow. Jobless and not having received her last pay, she goes hunting and runs across Bamba on a forest path. Terrified, she marches him at gunpoint to the border-patrol office, which is deserted because of the mission to capture the Afghans. She tries the Mayor (above), but is told to deal with him herself.

On the first night she ties him up in the yard but eventually allows him to sleep in a locked room on an air mattress. Gradually she becomes more hospitable, to the point where the villagers begin to gossip about her, doing the things that people shocked by interracial couples do–killing Svetlana’s dog and tossing rocks through the window.

In between such episodes Svetlana and Bamba talk to each other, he in perfect British-accented English and she in Bulgarian. We learn a lot about both, but they learn little about each other and can only convey ideas like “I want to wash your clothes” with hand gestures. Nevertheless gradually trust and even warmth are established.

One could argue that Bamba is a bit too close to being a Magic Negro. Not only does he speak perfect English, but he’s a medical doctor. He’s patient and polite and does his share of the chores around the house once Svetlana lets him in. Still, it’s hard to imagine a plausible plot in which a less respectable-looking, working-class black man could win her over in the same way. Plus he is an engaging character, and he makes the dour Svetlana turn into one, so we are unlikely to complain.

The film is shot in impressive black-and-white anamorphic widescreen. There is one spectacular shot that’s quite breathtaking. It’s a drone image, starting on a simple sea view, moving backward through an open-sided room in the building under construction, and continuing on and on to reveal an immense, rambling, unfinished complex.

Did some entrepreneur envision turning the town into a seaside resort and lose funding partway through? We never know, but it provides an odd contrast with the poverty of many of the residents of a seemingly failing town. The only connection to the plot is that the Afghans spend a miserable time trying to live there until the border patrol gives up and trucks them further into the country in search of a place that can deal with them.

Fear turned out to be one of my favorite films of the festival, alongside Sun Children. It’s available for streaming only in Wisconsin through tomorrow.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q&A sessions for many of the films.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Fear (2020)

Posted in Animation, Festivals: Wisconsin, Film comments, National cinemas: Eastern Europe, National cinemas: France, National cinemas: India |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Here and there open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Here and there

Tuesday | May 18, 2021

Keep Rolling (2020).

DB here:

Several of the films I’ve seen this go-round are either revived versions of older films, or recent films indebted to older traditions. Herewith, some thoughts on them.

Tender and tawdry

La Belle de nuit (1934).

I felt less dopey about not knowing about Louis Valray when Serge Bromberg, in an interview on the WFF site with Kelley Conway, confessed he’d not heard of him until he found an incomplete print of Escale (1935) by accident. Bromberg went on to find more footage, discover Valray’s first film, and secure the rights to restore and distribute them. Splendid in their restored versions (with curved corners on the frame), the films are at once generic and pleasingly perverse.

La Belle de nuit (1934) is a boulevard melodrama with hints of Vertigo and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne. When a playwright discovers his wife has cheated on him with his best friend, he plots vengeance. By chance (i.e., dramaturgy) he finds a prostitute who is almost a dead ringer for the wife. He dresses her up, installs her in an apartment, and coaxes her to adopt a remote, mildly mocking manner. Of course, the treacherous best friend is in a frenzy to possess her. Wait till he learns about the past of his new passion.

La Belle de nuit alternates rather flat scenes of bourgeois flirtation with bursts of cinematic energy. Like other early sound films, there are some sharp auditory transitions. Dynamic hooks link scenes with sounds, images, or both: automobile wheels, locomotives, phonograph records.. There are peculiar angles and, most noticeably, a fascination with the unattainable woman. As ever, cigarette smoke helps the mystique.

I suspect that Valray learned a lot from making this first film because I found Escale a more polished production. Like his debut, it centers on a fallen woman who hangs around hazy cafes where hard-used women stroll among tables and sing about the troubles of life. Jean, an uptight lieutenant on passenger ships, falls in love with Eva, who hangs around smugglers in her seaport town. Jean and Eva share an idyll, and she seems redeemed. But when Jean leaves on a voyage, Eva’s loyal manservant Zama can’t keep her from succumbing to the mesmeric bootlegger Dario.

Escale has more exquisite visuals than La Belle de nuit. Filmed on a lush Mediterranean island, it bathes its landscapes and sea vistas and seedy port with a languid melancholy akin to that of Pépé le Moko (1937). Practically every shot, on land or sea or in the alleys or the boudoir, yields brooding, hypnotic imagery.

I find Escale‘s villain far scarier than the fussbudget playwright of La Belle de nuit. Dario wears more mascara than Eva, but the effect is to give him the burning glance of the true monster.

Both films, available on French DVD, would be a fine double feature for an enterprising US disc publisher or streaming service. Thanks to Bromberg and Lobster Films, they can be seen in their full glory.

A Taiwanese revelation

Just as the Valray films cast a new light on 1930s French cinema, so The End of the Track (1970) puts the standard history of Taiwanese cinema into a fresh perspective. The story is that the New Taiwanese Cinema of the 1980s, developed by Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and others, created a fresh turn toward social realism and more adventurous storytelling. Their tales of rural life and urban anomie clashed with the entertainment genres of commercial cinema and the government-sponsored films asserting that under Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang regime life was buoyant and carefree. With The End of the Track we have a fine predecessor, a “parallel” film that dared formal and thematic opposition to the mainstream, and did so well before the New Wave directors.

Yung-shen’s father and mother run a noodle cart; Hsiao-tung’s family is well-off. But the boys are fast friends. They enjoy long days in their rural paradise–swimming naked, play-fighting, and exploring caves. The film’s first twenty-five minutes are almost plotless, built out of routines of school, play, and homework. But then a crisis strikes, and the film turns achingly sad in a quiet, unmelodramatic way. The plot shifts slowly to a study of how one boy becomes a surrogate son for a grieving family, while his own parents respond uncomprehendingly.

The boys’ skinny-dipping and mud wrestling earned the film a ban for “homosexual undertones and ideology.” There’s surely a homosocial, and maybe homoerotic undercurrent, but the main impression is that of devoted friendship and the heavy weight of obligation. One boy must leave childhood behind, too soon, and start a new life. Just as powerful is the class component. In one grueling sequence, Yung-shen’s parents try to push their cart through typhoon-swept streets as Hsiao-tung’s parents look on from their car.

Pictorially, director Mou Tun-fei makes full use of the glorious scenery that rural Taiwan can yield. He uses fast cutting, handheld shots, abrupt flashbacks, and other “modern cinema” techniques. These techniques can be seen in many commercial Taiwanese films of the period, but most directors used them to jazz up generic plots. Here, the fastidious black-and-white palette gives them a certain sobriety. The gravity is enhanced by severe but lyrical compositions, like this planimetric shot of the boys laying out a running track.

. .

Above all, the slow pace of the film–the basic story is almost an anecdote–allows Mou to soak us in the characters’ milieu. There are even some prolonged, static long shots that look ahead to the precisely unfolding scenes we get in Hou’s films and in Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991).

Mou is now, like Valray, a rediscovered director enjoying belated fame in his national cinema. In a very helpful discussion of his career, Wafa Ghermani and Victor Fan point out that there was at the period an important trend toward independent, low-budget films in Taiwanese (rather than the official language of Mandarin), and Mou’s work is just one example. As usual, a festival screening can remind us that there’s a lot more powerful cinema out there than we’ve realized.

Her time has come

Keep Rolling (2020) isn’t an old film, but it’s about a director who has over forty years quietly carved her own niche in world cinema.

In the 1980s, a new generation of filmmakers overturned Hong Kong cinema. Some, like Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, and John Woo, brought a turbocharged version of the New Hollywood to a film culture already energized by a tradition of martial-arts action. Other young talents formed what came to be called the Hong Kong New Wave. Although Tsui was sometimes identified with this, this trend was not so brash. It moved toward social realism, with directors like Allen Fong and Stanley Kwan exploring a modernizing Chinese culture living under colonial rule but forging its own identity.

Of all the New Wave directors, Ann Hui distinguished herself by her sincere and dogged attention to Hong Kong life as it is lived. After making some docudramas for television, she directed her first feature, The Secret (1979) and won festival attention with Boat People (1982) and Song of the Exile (1990). Although she has happily embraced genre films–she has made ghost stories and thrillers–she always treats sensational material with a calm, unspectacular attention to characterization and mood. Her swordplay film, the two part Romance of Book and Sword (1987), emphasizes landscape and interpersonal drama over action set-pieces. Who else would make Ah Kam (1996), a martial-arts movie centering on a stuntwoman?? She brought attention to social problems, sometimes in advance of social policies: caring for a parent suffering from dementia (Summer Snow, 1995), the need to shelter victims of marital abuse (Night and Fog, 2009), and lesbian rights in Hong Kong (All About Love, 2010).

In all, she has directed twenty-eight features. Every one has been a struggle.

Because the local market has been small, Hong Kong filmmakers have had to look abroad. For directors like Tsui and Woo, that meant making flamboyant action vehicles for audiences across East Asia, as well as for the Chinese diaspora and fans in other territories. But Ann Hui’s commitment to local life meant that her films had to gain wider attention on the red-carpet circuit. They did. Over the decades, they routinely played the major festivals. Her A Simple Life (2011) got a standing ovation when it played Ebertfest in 2014; Roger called it one of the year’s best films.

Last year Kristin and I were sorry we couldn’t be in Venice to watch her accept a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. In response to my email of congratulation, she was characteristically modest in facing a 14-day quarantine when she returned home. As ever, she makes personal contact:

Tonight I am dead beat n have a whole day of press tomorrow before I leave on the day after. I promise myself I’ll only stick to filmmaking from now onwards. How r u and is the pandemic bad in your area? HK is bad all the way you must know. Will u still come n visit us? Take care n keep well! Ann

Ann’s career receives a fitting tribute in Man Lim-chung’s Keep Rolling. It surveys her life, with fine interviews with her sister and brother, along with comments from friends and critics. There’s a lot of behind-the-scenes production footage. Above all, Man offers a personal portrait of her persistence and dedication. Virtually the only female director to make a career in Hong Kong, she has contributed to the world’s humanist cinema shaped by directors like Kurosawa, Kiarostami, and Satayajit Ray. Stubbornly sincere, with no PoMo flash or trickery, her small-scale studies of character always have wider social resonance. One can only hope that this film brings her–and her films, shamefully neglected on DVD–to more audiences.

The four films reviewed above are all available from the Festival across the USA until midnight Thursday. You can sign up here.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

For more on Ann Hui’s visit to Ebertfest, go here. We’ve reviewed many of Ann’s films on this site; check the category. I discuss trends in Hong Kong cinema in Planet Hong Kong and consider some aspects of Taiwanese film in Chapter 5, on Hou, in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. I sure wish I had known The End of the Track when I wrote that chapter.

The End of the Track (1970).

Posted in Directors: Ann Hui, Film comments, Film history, National cinemas: France, National cinemas: Hong Kong, National cinemas: Taiwan |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Retrospectating open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Retrospectating

Sunday | May 16, 2021

Sun Children (2020)

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival, online this year, continues through this coming Thursday. Films for which audience members buy tickets are all available to watch until 11:59 that night. So far our experiences have been that the streaming system works quite smoothly, with easy access to your chosen titles. Despite geo-blocking (dictated by distributors) in some cases, many films can be watched from outside Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Now, let’s visit the Middle East.

Iran: Sun Children and There Is No Evil

Despite the tragic death of Abbas Kiarostami and the exile into relative obscurity of the Makhmalbaf family, the Iranian cinema continues to produce important films by a small number of auteurs, most prominently Oscar-winner Asghar Farhadi (whose A Hero was recently acquired by Amazon for release later this year), Majid Majidi, the irrepressible Jafar Panahi, and his equally irrepressible colleague Mohammad Rasoulof.

The latter’s There Is No Evil (2020), which won last year’s Golden Bear as best film at the Berlin Film Festival, is on the current WFF program. I wrote about it last year from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Also on the program is Majidi’s latest, Sun Children, which we saw for the first time. Those who think of Iranian festival-oriented films as developing slowly and subtly will be surprised by this one. It is jam-packed with a multi-strand dramatic plot, suspense, fast cutting, and many characters, all handled very skillfully by Majidi.

The film begins with a dedication to the “the 152 million children forced into child labor and those who fight for their rights.” That child labor, as the exciting opening scene emphasizes, often involves small crimes. Four boys set out to steal a tire from a car in the parking garage of a luxurious, multi-storied shopping mall. The suspense begins right away as a guard confronts them. Two of them flee in a classic chase scene, going up through the levels of the mall, past high-end shops that they could never dream of entering. They escape, and it is revealed that the four friends work at a large repair shop, full of stacks of tires, presumably acquired in the same fashion.

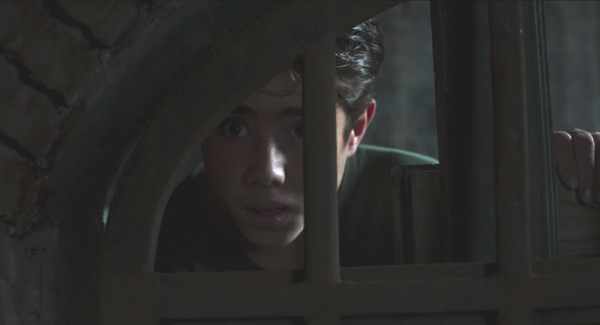

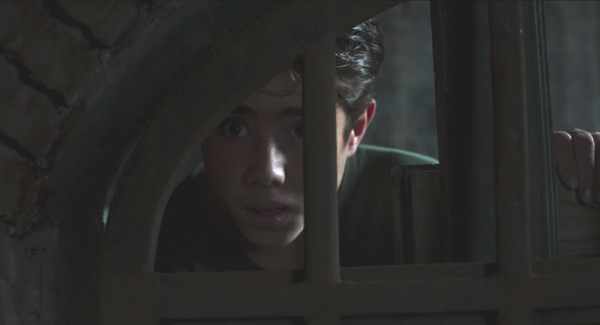

Soon Ali emerges as our point-of-view character, desperate to rescue his mother from a mental-health facility. There she lies strapped to a bed after a presumed suicide attempt. Eventually it emerges that the family home recently burned, killing Ali’s sister, whose death drove his mother mad. His father is an addict, and Ali has become the breadwinner. A small-time crime boss sets him a task: enroll in a local school and explore the basement and tunnels under it (above), where a treasure is hidden.

Much of the rest of the film generates more suspense, as Ali diligently makes his way around various obstacles and crawls through branching tunnels day after day, always risking expulsion from the school if he is discovered. His three friends help him at first, but eventually he is left to traverse the seemingly endless tunnels (which are in fact the city’s storm drains).

This part of the film introduces another major plotline, since the school, dependent on private donations, is located in the slums of Tehran. Its aim is to teach young, desperate, potentially criminal boys skills that they can use to get honest jobs. The school is far behind on its rent and in danger of being closed. This adds further suspense as the school officials, particularly a sympathetic vice principal, struggle to find donors. The schools debts lead to one of the film’s big action scenes, as, finding the gates locked one morning, the principal urges the boys to scale the fence. They do this with a determination that reveals their realization that their only hope for a decent life lies in the education they have been receiving.

They eagerly participate in a festival and pageant put on for potential donors (top).

In an interview, Majidi said that the “Sun School” that gives the film its name is based on an actual school in the Tehran slums, the “Sobhe Rooyesh” (“Morning of Growth”). The non-professional child actors, whose performances are all completely natural and affecting, were recruited from the school and surrounding slums. Roolholloh Zammi, who plays Ali, won the Marcello Mastrioanni Award at Venice last year. (I wish we could have been there to see him win!) Only the adults are played by [professional actors.

Israel: Here We Are (2020)

Given the current situation in Israel, it is just as well that Nir Bergman’s gentle psychological study Here We Are (a sadly unmemorable title) has no reference at all to politics, the military, or ethnic tensions. It’s a simple story of a man who has given up his career to care for his severely autistic son and is having difficulties facing the fact that the boy is nearly a man.

The early scenes set up Uri’s disabilities, as well as his obsessions (including pet goldfish–above–and dogs) and phobias (snails). They also establish Aharon’s utter devotion and patience as he cooks yet again Uri’s favorite pasta stars and uses an obviously well-established imitation game to coax his son past imagined snails on a biking route.

The plot action kicks in when Ahron’s estranged wife Tamara shows up, determined to arrange Uri’s transfer to a group home for young people with disabilities. Ahron angrily resists, claiming that Uri is happy at home and that he can care for his son himself.

We seem to be set up to view Ahron as the noble, self-sacrificing father and his wife as the shrewish woman who wants to dictate her son’s life. Eventually, however, Tamara obtains the legal papers requiring Ahron to bring Uri to his new home. Ahron sets out, but along the way he decides to go on the run with Uri, despite having little money.

Along the way there are growing hints that Ahron is stifling both Uri and himself. Twice he simply ignores Uri’s budding sexuality during encounters with young women.

The two seek shelter with an old friend of Ahron’s, Effi, an art teacher who reveals that Ahron had had a prominent and lucrative career as an artist and designer, which he had given up to care for Uri. Her attitude toward Ahron suggests her openness to a romantic relationship with him. Eventually we begin to doubt that he is acting in the best interests of himself and Uri, especially during a scene in which they are forced to dine on ice-cream sandwiches in a bus-station waiting-room.

Here We Are is a film that unfolds gradually and overturns your expectations slowly but thoroughly.

France-Lebanon: Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Chloe Mazlo is a French animator and artist who has previously made shorts (including The Little Stones, which won the 2015 César for Best Animated Short). Inspired by her grandparents’ life in Lebanon (he was Lebanese, she Swedish) during the lengthy civil war, she has made a feature that combines occasional animation with live action.

The film starts out in a stylized, fantastical world that inevitably has led critics to compare Skies of Lebanon to Amélie (2001). Alice, the heroine, is alienated from her parents and her home country, Switzerland, and take a job as a nanny in Beirut. The city as it was in the 1950s is represented by matte shots of actors presumably filmed against a green-screen, with backgrounds filled in by blow-ups of tinted postcards of the period. Such shots have a charming effect.

Alice meets cute with a handsome physicist whose goal is to invent a rocket to put the first Lebanese astronaut into space. Their romance develops in a fantasy landscape of patently artificial rocks and stars (bottom). They settle down together, raise children, and pursue their careers, with Alice becoming a watercolorist.

The fantasy strain in the film is most obvious in the brief animated scenes, as when a split-screen telephone conversation juxtaposes the real Alice with puppets representing her angry parents, who demand that she return home (top of section).

About a third of the way into the film, the tone switches abruptly as the Lebanese civil war breaks out. The animations and postcard background disappear. As characters flee and disappear mysteriously, a shot of a wall with “have you seen” photos pasted up emphasizes the danger that Alice is trying to ignore.

Even during the lengthy wartime portion of the film, there remains a faint underlying humor. Yet the abrupt shift of tone when the war starts is unsettling, given that we had settled down for a whimsical romance and end up with a war story. Presumably the idea is to emphasize how war breaks into the calm of ordinary life and banishes it. Whether audiences will take it that way is another matter. On the whole, however, the film is an imaginative and promising first feature.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Posted in Festivals: Wisconsin, National cinemas: Iran, National cinemas: Israel, National cinemas: Middle East |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021 visits the Middle East open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021 visits the Middle East

Friday | May 14, 2021

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

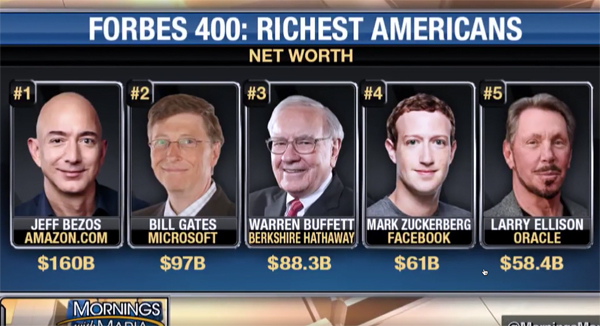

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

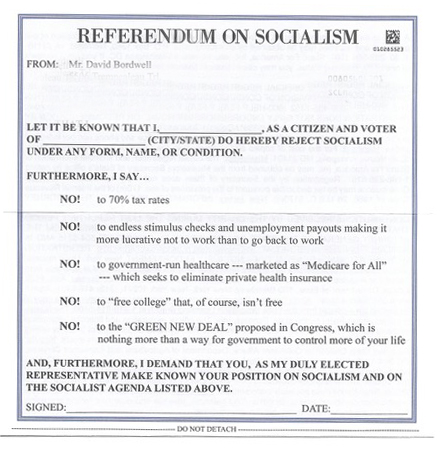

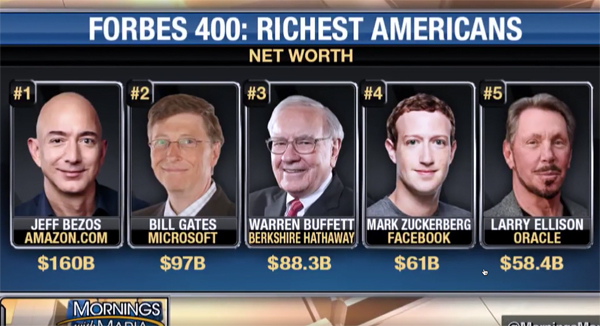

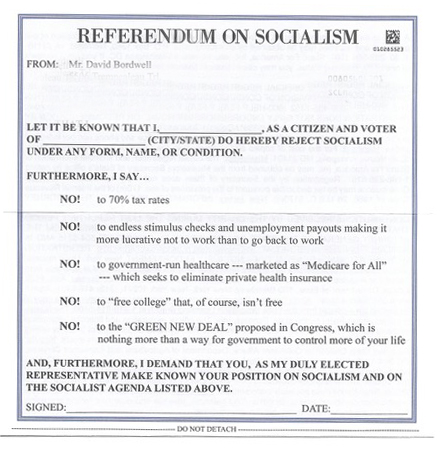

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

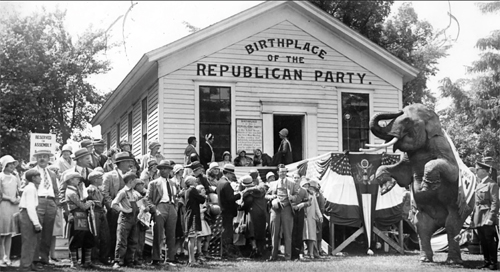

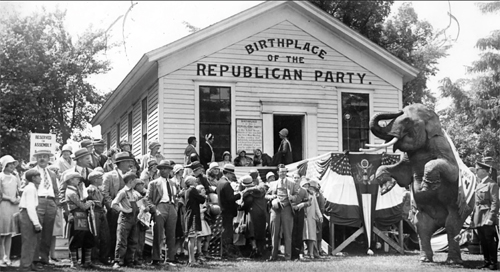

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

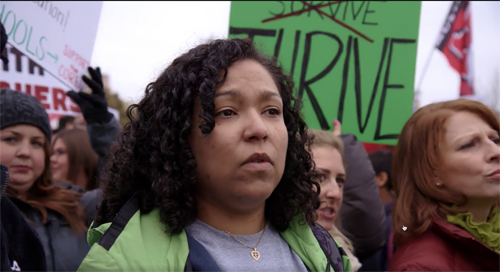

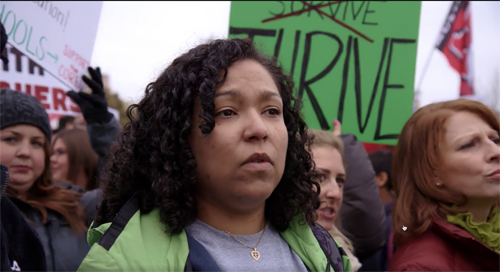

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

The Passionate Thief (1960).

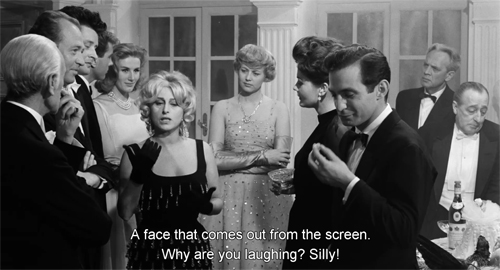

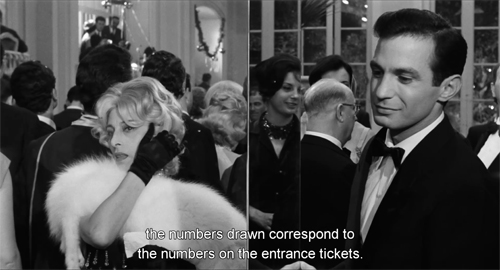

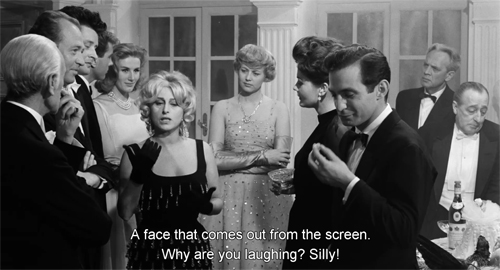

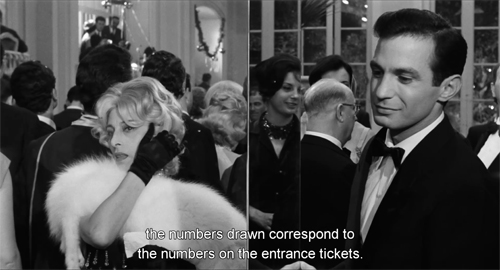

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).

Posted in Documentary film, Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato, Festivals: Wisconsin, Film comments, National cinemas: Italy |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

|