Friday | February 5, 2021

Mitra (2021)

Kristin here:

On Saturday morning (8:30 am our time), the International Film Festival Rotterdam will be screening its annual Surprise Film. We’re naturally curious to learn what it is. But Rotterdam comes so early in the year that often we go into its other offerings knowing almost nothing about them. Here are two of the very pleasant surprises from recent days.

Iranian cinema from the Netherlands

Kaweh Modiri, the director of Mitra, was born in Iran but has lived in the Netherlands since he was six years old. Still, he remains concerned with Iranian issues and clearly has been influenced by the flourishing Iranian art cinema of recent decades.

Asghar Farhadi’s success in international festivals and territories has been the most influential instance recently, at least outside of Iran. His plots are often built around conflicts, not between good and bad people, but behind people who clash because of cross-purposes. Late revelations and tortured discussions lead to reconciliations that are not the happy endings of Hollywood films but instead are resigned agreements to admit mistakes and make compromises.

Mitra is such a film, but it is based around more politically based conflicts than Farhadi has used–ones that have life and death consequences for those involved.

The film moves between two settings and eras: Tehran in 1981-82, the years shortly after the ouster of the Shah, and the Netherlands in 2019, the fortieth anniversary of that revolution. The opening is set in 1982, when the heroine, Haleh, receives an abrupt, unexpected telephone calls announcing that her daughter Mitra has been executed. We move then to 2019, when Haleh, now an academic in the Netherlands, addresses a conference on “The Islamic Revolution at Forty.” Soon she is visited by members of “The Organization,” a group aimed at bringing down the current government of Iran. They tell Haleh that Leyla, whose betrayal of Mitra caused her death, has arrived with her daughter in the Netherlands. She goes under the name Sale, having appealed for refuge status. The Organization wants Haleh’s confirmation that Sale is indeed Leyla.

The rest of the plot centers around a shifting relationship, as Haleh vows revenge on Leyla. Her goal is complicated by the fact that she has never actually seen Leyla, having only heard her voice. Nevertheless, she calls Sale and is convinced that she recognizes the woman’s voice, even after nearly forty years. Once they meet, however, Haleh seemingly bonds with Sale and her endearing daughter Nilu. Indeed, Haleh’s attraction to Nilu hints at her possible acceptance of Sale as a substitute daughter and Nilu as a granddaughter.

Interspersed with this story are flashbacks to the younger Haleh’s 1981 experiences, when Mitra, who has joined the resistance in Iran, is still alive. Scenes like a clandestine meeting with Mitra at a crowded market emphasize Haleh’s love for her daughter (top of section).

Modiri expertly lures us into sympathizing with all the characters involved. To the end we remain uncertain as to whether Sale, who after some doubts accepts Haleh as a friend and even as a substitute mother in a new land, is actually the treacherous Leyla. Even if she is, is it worth ruining young Nilu’s life to turn Sale in to the ruthless Organization?

Supporting all this is Haleh’s relationship with her brother Mohsen, who at first seems a somewhat comic, eccentric sidekick but is later revealed to be suffering the effects of torture and lengthy imprisonment in Iran. His exchanges with Haleh initially seem like sibling bickering, but he becomes the moral compass that holds her together as she pursues revenge (see top).

Mitra starts out seeming to be a conventional revenge story, but its moral and personal shifts and surprises lead to a moving and not-quite-resolved ending.

The film has had its world premiere at the IFFR and is due for a May 20 release in the Netherlands. I hope it plays other festivals and travels further, because it is a definite contribution to the continuation of world interest in Iranian cinema. Like other such Iranian films, it had to be made elsewhere (the scenes set in Iran were shot in Jordan), but it carries forward what we have loved about Iranian films.

An Australian surveillance-cam thriller

Jonathan Ogilvie’s Lone Wolf (2021) adopts the new convention of creating a story based largely on surveillance and cell-phone footage. In a frame story Kylie, a Special Crimes Sergeant, bursts into the office of an unnamed Police Commissioner and demands that he watch a video she has secretly compiled from a mass of such footage.

The inner story is seemingly set more-or-less in the present day, but it’s a slightly alternative world in which surveillance has become even more pervasive than it already is. The read-outs in the images reveal that cameras are spying on the characters from such household devices as TVs and smoke detectors. One of these is, ironically, in a bathroom where Winnie sneaks the occasional cigarette by an open window (above). How Kylie gets access to all of these is never explained, and the premise is implausible–especially in scenes built around extensive, undamaged footage which she has somehow managed to extract from a phone that has been through a bomb explosion.

If one stifles such doubts, however, the tale Kylie’s film tells is an absorbing one, full of twists and turns. It centers on Conrad and Winnie, a couple who run a book/video-rental/sex shop and do occasional jobs for underground political groups. They are not the most appealing characters, but they gain our sympathy through their devotion to Winnie’s charming little brother Stevie, who has Down’s Syndrome and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

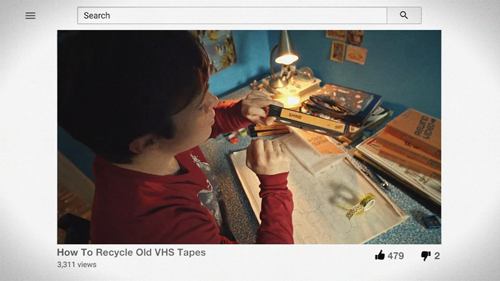

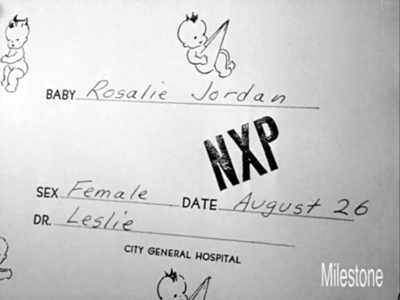

Australia is soon to host a G20 meeting, and a man from a radical group asks Conrad to set up a “victimless atrocity” in the form of a bomb explosion in a deserted area. At first Conrad refuses, but when offered a large sum, he gives in. Despite the grimness of this plot thread, there is quite a bit of humor in the film, provided by Stevie and by a group of Conrad’s misfit friends who gather to play cards above the shop. The combination of found footage also creates occasionally amusing moments, as when the film-within-a-film includes an instructional YouTube-style video that Stevie has posted or poor-quality footage from an old security camera in the shop that Winnie and Conrad think has been turned off (bottom).

The consequences of the bomb plot introduce a grim twist, but the return to the frame story creates a more gratifying one as Kylie reveals why she has pressed her video upon the Commissioner.

While Rotterdam provided Lone Wolf‘s world premiere, it has a distributor in Australia, though its August, 2020 release was postponed by the pandemic. Ogilvie hopes it will have wide theatrical play after a possible in-person premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival this coming August.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to discover these surprises!

Lone Wolf (2021)

Tags: Festivals: Rotterdam

Posted in Festivals, Film comments, National cinemas: Australia, National cinemas: Iran |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Rotterdam surprises open printable version

| Comments Off on Rotterdam surprises

Tuesday | February 2, 2021

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

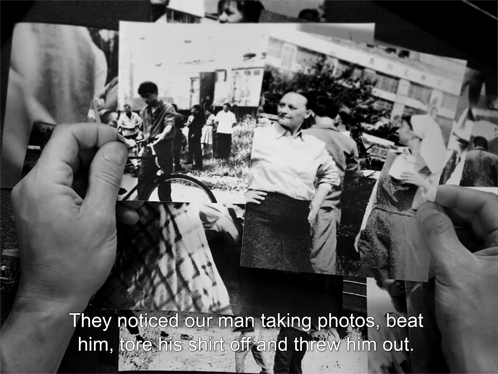

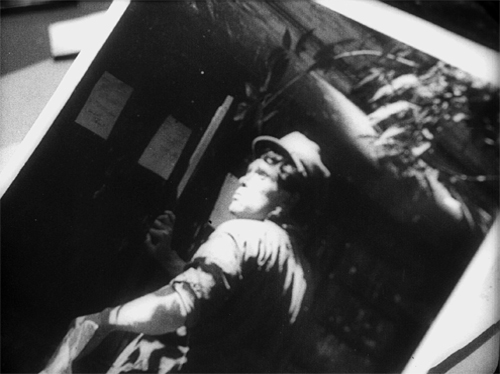

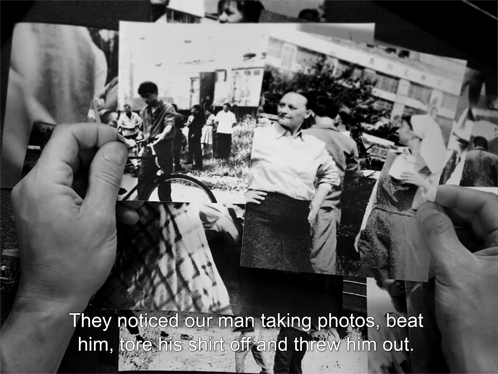

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).

Posted in Directors: Eisenstein, Festivals, Film comments, Film history, National cinemas: Denmark, National cinemas: Russia and USSR |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Rotterdam starts strong open printable version

| Comments Off on Rotterdam starts strong

Sunday | January 24, 2021

Kreise (Circles, 1934).

Kristin here:

Recently I acquired discs of the work of two important German directors of the silent and early sound periods. The first is a new Blu-ray/DVD edition of Paul Leni’s Waxworks from Flicker Alley. The second is a pair of DVD releases of Oskar Fischinger shorts, which I recently ordered from The Center for Visual Music, co-founded by Fischinger’s daughter Barbara. All are vital for anyone interested in these two major figures in German film history.

Telling scary stories

As with so many cinema classics, I first saw Paul Leni’s Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks) during my grad-school years. The print was 16mm and very dark. It was hard to get any real sense of its pictorial design. I had seen Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in my first film course and had been hugely intrigued by how different it was from the movies I was used to. It was one of the films that lured me into cinema studies. Since then I have been partial to German silents of the 1920s and especially those of the Expressionist movement. Waxworks was made in 1924, which also saw such high points of the decade as Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, and Carl Dreyer’s second German-made film, Michael. Still, the poor print did not give much sense of how it fit into the creative trends of the mid-1920s. Later I saw it in a 35mm archival print on a flat-bed viewer. That print was also too dark to allow a judgment of its aesthetic and historic importance.

At last, however, a restoration by the Deutsche Kinemathek and the Cineteca di Bologna (released on combination Blu-ray and DVD by Flicker Alley in the USA, from the British Eureka! print) has revealed the set design and impressively bold lighting that suggest why it is considered one of the classics of the Expressionist movement.

While Expressionist stage plays had tended to use stylized settings and acting to create frantic denunciations of contemporary politics and society, German Expressionist films usually remained within popular genres. Horror, fantasy, and science fiction could justify the distortions of the sets as ways of creating strange, often menacing worlds. Waxworks fits right into the horror genre. Set in a carnival sideshow booth, the frame story sets up the premise of the proprietor hiring a young man to write publicity tales about three wax figures of monstrous figures from history and legend: Caliph Haroun-al-Raschid, Ivan the Terrible, and Jack the Ripper. We see the three tales played out as the hero writes them.

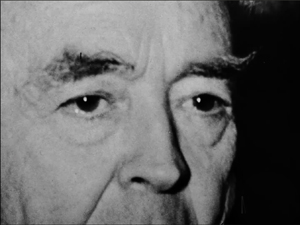

The villains are played by Emil Jannings (see bottom), Conrad Veidt, and Werner Krauss, three top male stars of the era. They do not, however, appear together, since their stories are self-contained vignettes. The narrative returns between the imbedded stories to the table where the young man writes and a romance quickly blooms between him and the sideshow owner’s daughter. The two actors playing them, Wilhelm Dieterle (later to have a career as a director in Hollywood as William Dieterle) and Olga Belajeff, appear as the central victimized couple in each inner tale.

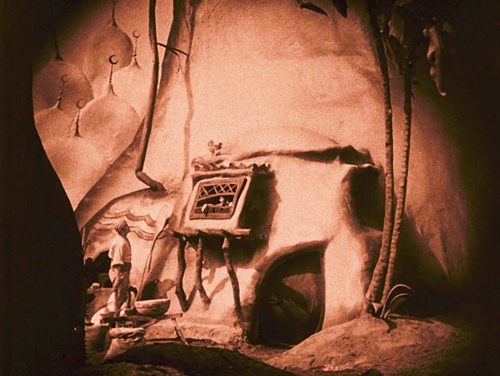

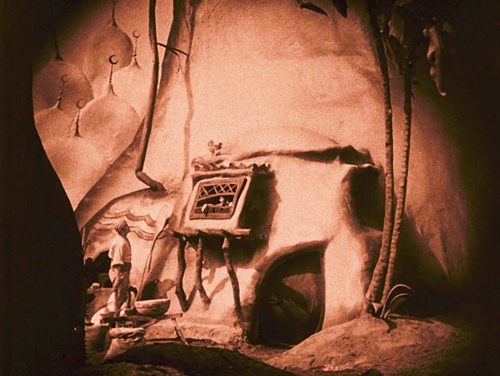

A different style is used for each of these three tales. The first story (in this print, at least) tells of Haroun trying to seduce the beautiful wife of a Baghdad baker. The settings are of the melting-clay variety familiar from Der Golem and Kriemhild’s Revenge. The image at the top of this section shows the baker’s home, with its sagging doorway and artificial trees. The image below displays a typical technique of designing sets to echo the shapes of the actors, as the doorway in the rear imitates Haroun’s blobby outline in the foreground.

The Ivan the Terrible episode comes next, maintaining the blobby look, but with more solid-looking, often symmetrical sets. Here Ivan emerges from his palace.

The brief third episode has suspenseful visions of Jack the Ripper pursuing the couple in nightmare fashion, with multiple superimpositions of the implacable killer.

Apart from these techniques, the improved visual quality of the film reveals a dark style of lighting that helps explain where the influences on Hollywood film noir came from. The opening of the frame story takes place at night, and a chiaroscuro look is established with a sophisticated use of Hollywood’s three-point lighting, which had only reached Germany a few years earlier.

There are some other daring uses of foreground silhouettes, as when the jealous baker watches his wife move away into darkness (left) or Ivan’s poison-maker realizes that he has been doomed to die (right).

These are only a few of the many frame-grabs I made while watching this visually dramatic print. I could post many more, but I’ll end with this interesting comparison that I noticed. On the left, a shot from the Haroun episode as he plays chess with courtiers, and on the right, an interior of the house where the Woman from the City is lodging in Murnau’s Sunrise (1927).

The Waxworks we see today is not the original German version. The original negative was lost in a Paris customs-house fire in 1925. The most complete surviving version was the one released in the UK in 1926. Where it was deteriorated, footage from other surviving release prints was substituted. This English version was about 25 minutes shorter than the German one, with the footage removed mainly from the frame story and from the exposition about the wedding of the young couple in the Ivan episode. The premiere of the film in Berlin had the stories in a different order: Ivan, then Jack, than Haroun. Possibly this aimed at a more cheerful ending for the film, but the order was changed shortly thereafter, presumably to that of the British and other release versions.

The severe hyperinflation in Germany in the mid-1920s led to financial problems, and these curtailed the shooting of the film. One intended episode about Rinaldo Rinaldini, a fictional “Robber Captain,” was never shot, though the wax figure of Rinaldini is clearly visible in the sideshow lineup of miscreants. The Jack the Ripper story was never shot in full, though the shapeless nightmare sequence was shot without benefit of script. It ends up as a short but frightening climax to the film. As a result of all this, the Haroun episode is fairly lengthy, the Ivan one less so, and the Jack the Ripper one brief but memorable. Essentially what we have is a restoration of the British version.

The restored version uses the intertitles from the British print, as the German ones have not survived, and the tinting and toning are also based on the British print. The accompanying booklet has an essay on the history of the film and its versions by Richard Combs, a sketch of Leni’s career by Philip Kemp, and a description of the restoration by Julia Wallmüller. Adrian Martin contributes the insightful commentary. One charming extra is a short, Rebus-Film Nr. 1 (1926), part of a series of eight brief crossword-puzzles that audiences could play along with in the program of short subjects before the feature. These included animations and experimental montage-style superimpositions done by the brilliant German cinematographer Guido Seeber. I got all the answers right. Could you? (Actually, they’re very easy, as they would have to be in a theatrical situation.) The Blu-ray is regions A, B, and C. For more technical and historical background on the film, see Jan Christopher-Horak’s review of the Flicker Alley release. (It’s entry number 260; you’ll need to scroll down to find it.)

Leni continued on in the horror mode late in his career in Hollywood, making The Cat and the Canary (1927), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and The Last Warning (1928), all at Universal. These, along with the various films of Lon Chaney, notably The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1922) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), built the foundation for Universal’s famous horror films of the 1930s.

The Visual Music of Oskar Fischinger

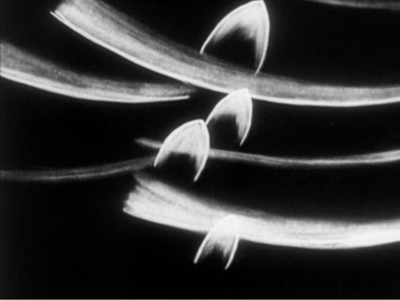

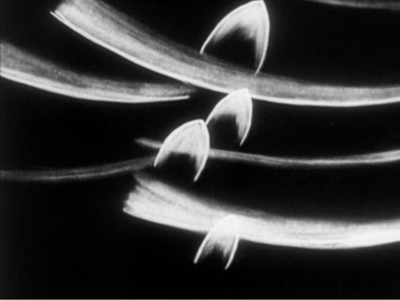

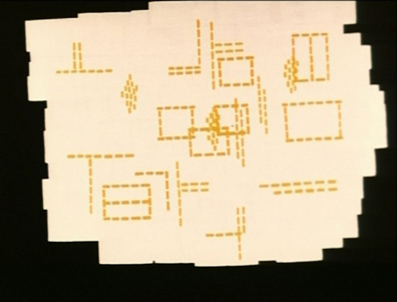

In my recent year-end entry “The Ten Best Films of … 1930,” I included Oskar Fischinger’s series of “Studies” from that year: short films of white shapes (drawn in charcoal on white paper and shown in negative) zipping around the screen in time to musical pieces. These run from Study No. 2 to Study No. 7, though others numbered up to 12 were made in 1931-32. Study No. 4 is apparently lost, and No. 1 is listed on the Fischinger Archive website (linked below) as having been accompanied by live organ music and never released on home video, while the subsequent ones were done with recorded music.

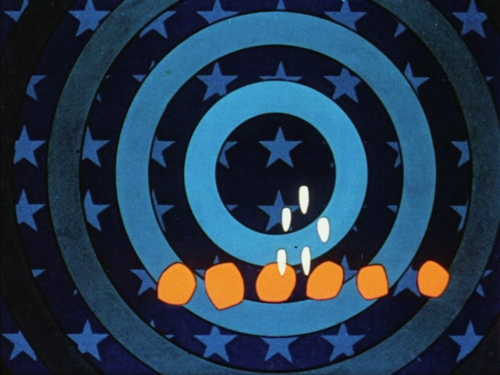

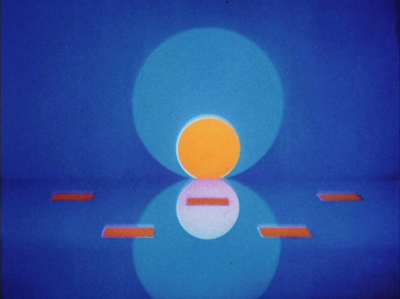

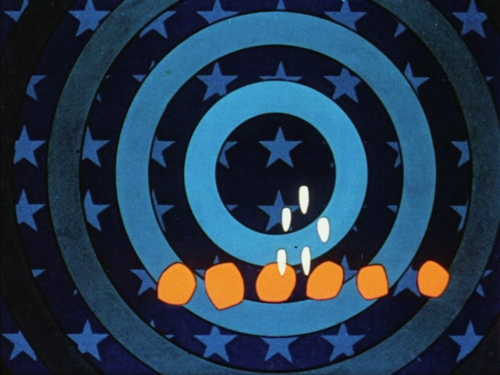

In that entry I linked to the Center for Visual Music as the sole source of two DVDs collecting Fischinger’s work. (I have discovered one other source. See the end of this entry.) At the time I had ordered them, and they subsequently have arrived. It was a great pleasure to sit down and watch both straight through. The films are delightful and lift the spirits. My viewing was on Inauguration Day, when my spirits were already quite lifted, and Fischinger’s An American March (1941), set to Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (above), was especially cheering on a day when our country got rid of a fake president and welcomed a real one.

Although Fischinger used both popular and classical pieces, he retained a similar, recognizable style for both. The black-and-white films were relatively simple, as in Study No. 6.

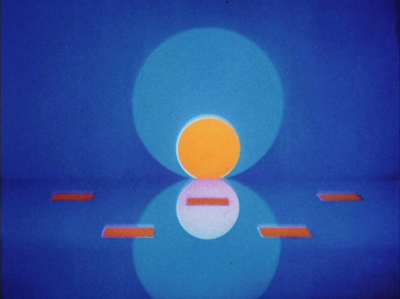

Like his contemporary, New Zealand animator Len Lye, Fischinger adopted color early and used the soft but extraordinarily vibrant Gaspar Color system. Most of his films of the 1930s employed it, as in Circles (at top) and Composition in Blue (1935).

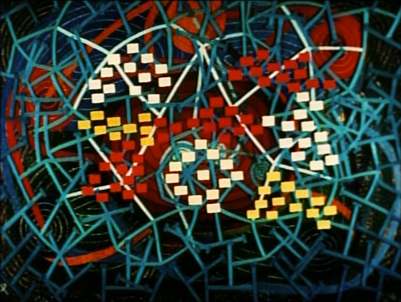

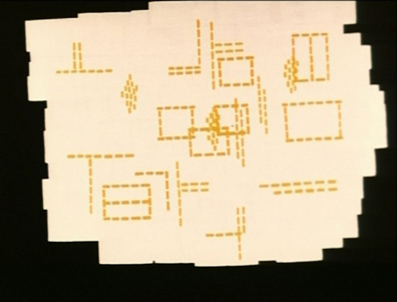

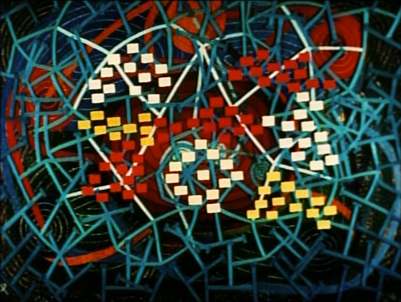

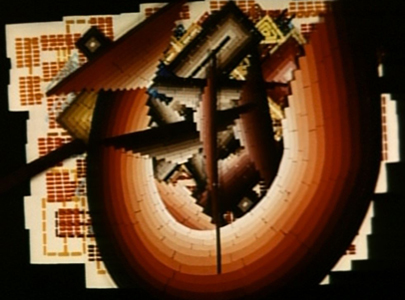

His masterpiece, at least in my opinion, is his last significant film, Motion Painting No. 1. It is his longest film at eleven minutes and is set to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3. It also departs from his usual modes of animation. Rather than substituting a new drawing or moving abstract shapes in space slightly between exposures, he added a brushstroke per frame, creating a continuously moving line that gradually created a series of compositions that changed the image completely as the line proceeded relentlessly and obliterated what went before. Thus across the film there is no pause in the line’s movement as it paints over its earlier progression. Here are some of the stages of its mutations. (Spoiler alert!)

While these two discs contain nearly all of Fischinger’s important films, a conspicuous absence is An Optical Poem, which is an abstract animation of the usual sort made by Fischinger but for a major studio. MGM produced it as one of the seven-minute cartoons that were shown among the shorts in movie-theater programs for decades. Set to Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody Number 2,” it’s typical Fischinger, with lively colored discs and other shapes darting around. The main difference is that here he was working in Technicolor. As smaller discs pass behind larger ones, a distinct sense of depth is often achieved.

The reason for An Optical Poem‘s absence from the CVM discs is presumably because it is the only Fischinger film not controlled by the Estate. Fortunately the gap has been filled by its inclusion in Flicker Alley’s set, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970,” which I reviewed when it was released in 2015. Flicker Alley obtained permission from Warner Bros. and Turner Entertainment, which now control MGM’s library. This allowed them to include the original MGM logo and title, plus an introductory opening text that tries to prepare the audience for what’s to come. (These are missing from the prints posted online.)

Between the two CVM discs and the Flicker Alley set, we now have good copies of all but some minor, often unfinished works by Fischinger. The CVM discs do not contain much in the way of supplements, but one can get much more information from William Moritz’s Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger (2004). More information, including a bibliography of books and articles on the filmmaker, can be found on the website of CVM’s Fischinger Archive. Fischinger died in 1967, and several years later his wife Elfriede sent a collection of his equipment and the material used in his animated films to the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt. This collection included the plexiglass sheets upon which Motion Painting No. 1 was created.

Thanks to Lee Tsiantis for a correction to the Oskar Fischinger section!

January 27, 2021. Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for providing some additional information on the availability of Fischinger’s films. A number of art museums and specialty bookshops have sold the CVM DVDs in the past. The only place that is still doing so, as far as I can tell, is Walther Koenig‘s fine bookshop in Berlin. The CVM also has some excerpts and complete films on their Vimeo channel.

Posted in Animation, Covid-19 cinema, Experimental film, Film history, National cinemas: Germany |  open printable version

| Comments Off on German classics for the pandemic and beyond open printable version

| Comments Off on German classics for the pandemic and beyond

Tuesday | January 19, 2021

We have never reposted an entry before, but given recent events in US history, and the celebration of Martin Luther King’s legacy yesterday, and the impending inauguration of a new president tomorrow, we are re-running this entry, unrevised, from nearly four years ago.

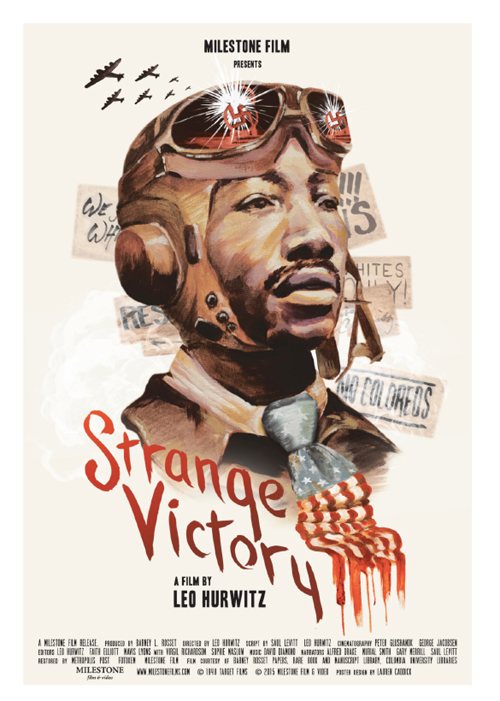

It’s not just that it remains timely. (The interpolations remind us that Trump has been inciting violence from the start.) We wanted also to note that thanks to Milestone Films you can stream Strange Victory here. I plan to write more about the end of the Trump era in the days to come, but for now we can acknowledge the struggles ahead of us. We can be strengthened by recognizing that in 1948 people who had sacrificed far more than we have still sustained an urge to fight for decency and justice. –DB

DB here:

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today. my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

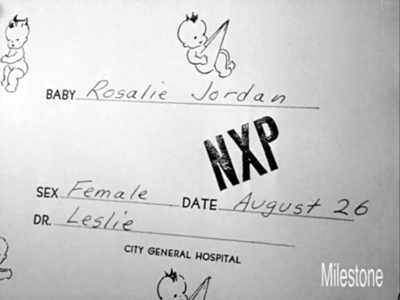

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.” Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.) 16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).

Posted in Documentary film, Film comments, Readers' Favorite Entries |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Repost: Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948) open printable version

| Comments Off on Repost: Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

|

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.