Sunday | January 24, 2021

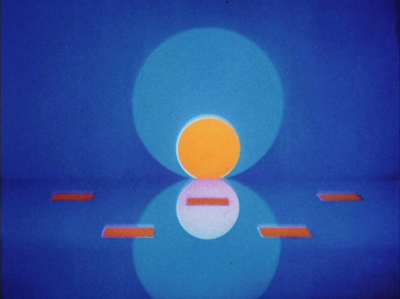

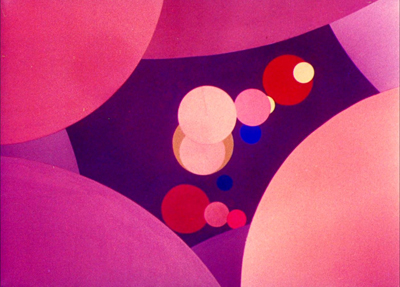

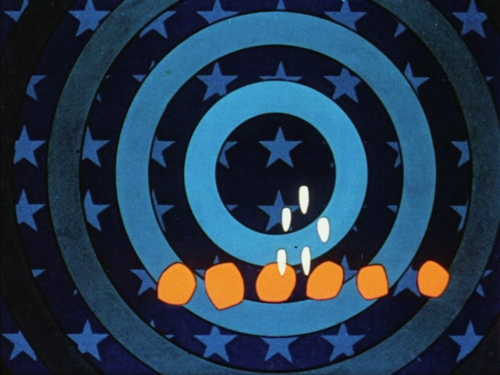

Kreise (Circles, 1934).

Kristin here:

Recently I acquired discs of the work of two important German directors of the silent and early sound periods. The first is a new Blu-ray/DVD edition of Paul Leni’s Waxworks from Flicker Alley. The second is a pair of DVD releases of Oskar Fischinger shorts, which I recently ordered from The Center for Visual Music, co-founded by Fischinger’s daughter Barbara. All are vital for anyone interested in these two major figures in German film history.

Telling scary stories

As with so many cinema classics, I first saw Paul Leni’s Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks) during my grad-school years. The print was 16mm and very dark. It was hard to get any real sense of its pictorial design. I had seen Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in my first film course and had been hugely intrigued by how different it was from the movies I was used to. It was one of the films that lured me into cinema studies. Since then I have been partial to German silents of the 1920s and especially those of the Expressionist movement. Waxworks was made in 1924, which also saw such high points of the decade as Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, and Carl Dreyer’s second German-made film, Michael. Still, the poor print did not give much sense of how it fit into the creative trends of the mid-1920s. Later I saw it in a 35mm archival print on a flat-bed viewer. That print was also too dark to allow a judgment of its aesthetic and historic importance.

At last, however, a restoration by the Deutsche Kinemathek and the Cineteca di Bologna (released on combination Blu-ray and DVD by Flicker Alley in the USA, from the British Eureka! print) has revealed the set design and impressively bold lighting that suggest why it is considered one of the classics of the Expressionist movement.

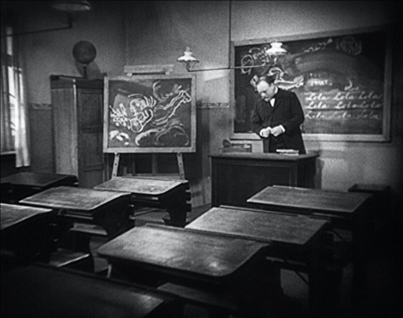

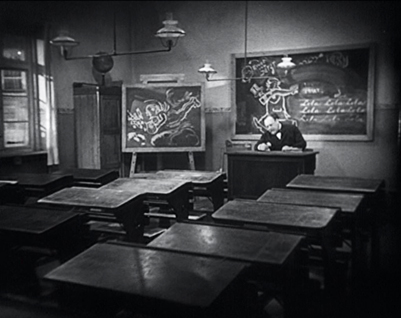

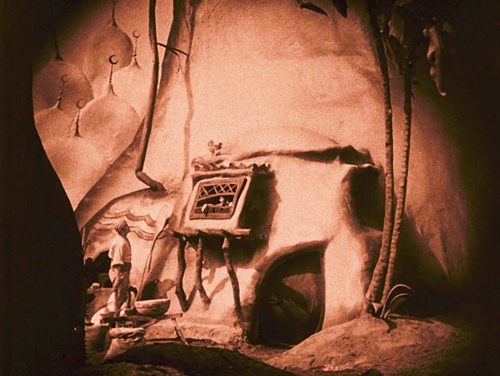

While Expressionist stage plays had tended to use stylized settings and acting to create frantic denunciations of contemporary politics and society, German Expressionist films usually remained within popular genres. Horror, fantasy, and science fiction could justify the distortions of the sets as ways of creating strange, often menacing worlds. Waxworks fits right into the horror genre. Set in a carnival sideshow booth, the frame story sets up the premise of the proprietor hiring a young man to write publicity tales about three wax figures of monstrous figures from history and legend: Caliph Haroun-al-Raschid, Ivan the Terrible, and Jack the Ripper. We see the three tales played out as the hero writes them.

The villains are played by Emil Jannings (see bottom), Conrad Veidt, and Werner Krauss, three top male stars of the era. They do not, however, appear together, since their stories are self-contained vignettes. The narrative returns between the imbedded stories to the table where the young man writes and a romance quickly blooms between him and the sideshow owner’s daughter. The two actors playing them, Wilhelm Dieterle (later to have a career as a director in Hollywood as William Dieterle) and Olga Belajeff, appear as the central victimized couple in each inner tale.

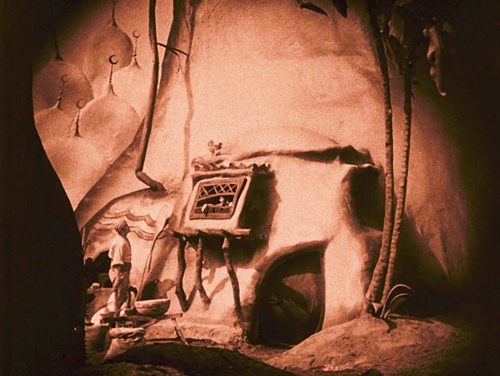

A different style is used for each of these three tales. The first story (in this print, at least) tells of Haroun trying to seduce the beautiful wife of a Baghdad baker. The settings are of the melting-clay variety familiar from Der Golem and Kriemhild’s Revenge. The image at the top of this section shows the baker’s home, with its sagging doorway and artificial trees. The image below displays a typical technique of designing sets to echo the shapes of the actors, as the doorway in the rear imitates Haroun’s blobby outline in the foreground.

The Ivan the Terrible episode comes next, maintaining the blobby look, but with more solid-looking, often symmetrical sets. Here Ivan emerges from his palace.

The brief third episode has suspenseful visions of Jack the Ripper pursuing the couple in nightmare fashion, with multiple superimpositions of the implacable killer.

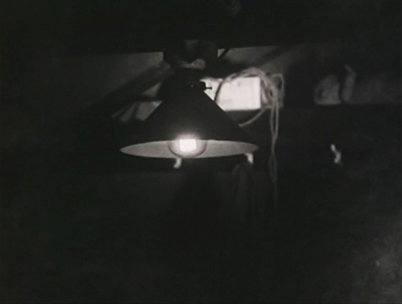

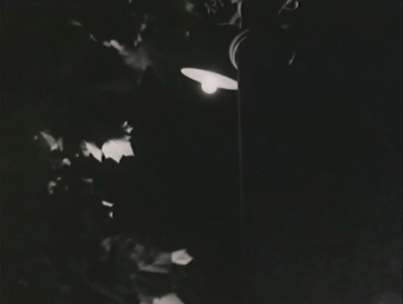

Apart from these techniques, the improved visual quality of the film reveals a dark style of lighting that helps explain where the influences on Hollywood film noir came from. The opening of the frame story takes place at night, and a chiaroscuro look is established with a sophisticated use of Hollywood’s three-point lighting, which had only reached Germany a few years earlier.

There are some other daring uses of foreground silhouettes, as when the jealous baker watches his wife move away into darkness (left) or Ivan’s poison-maker realizes that he has been doomed to die (right).

These are only a few of the many frame-grabs I made while watching this visually dramatic print. I could post many more, but I’ll end with this interesting comparison that I noticed. On the left, a shot from the Haroun episode as he plays chess with courtiers, and on the right, an interior of the house where the Woman from the City is lodging in Murnau’s Sunrise (1927).

The Waxworks we see today is not the original German version. The original negative was lost in a Paris customs-house fire in 1925. The most complete surviving version was the one released in the UK in 1926. Where it was deteriorated, footage from other surviving release prints was substituted. This English version was about 25 minutes shorter than the German one, with the footage removed mainly from the frame story and from the exposition about the wedding of the young couple in the Ivan episode. The premiere of the film in Berlin had the stories in a different order: Ivan, then Jack, than Haroun. Possibly this aimed at a more cheerful ending for the film, but the order was changed shortly thereafter, presumably to that of the British and other release versions.

The severe hyperinflation in Germany in the mid-1920s led to financial problems, and these curtailed the shooting of the film. One intended episode about Rinaldo Rinaldini, a fictional “Robber Captain,” was never shot, though the wax figure of Rinaldini is clearly visible in the sideshow lineup of miscreants. The Jack the Ripper story was never shot in full, though the shapeless nightmare sequence was shot without benefit of script. It ends up as a short but frightening climax to the film. As a result of all this, the Haroun episode is fairly lengthy, the Ivan one less so, and the Jack the Ripper one brief but memorable. Essentially what we have is a restoration of the British version.

The restored version uses the intertitles from the British print, as the German ones have not survived, and the tinting and toning are also based on the British print. The accompanying booklet has an essay on the history of the film and its versions by Richard Combs, a sketch of Leni’s career by Philip Kemp, and a description of the restoration by Julia Wallmüller. Adrian Martin contributes the insightful commentary. One charming extra is a short, Rebus-Film Nr. 1 (1926), part of a series of eight brief crossword-puzzles that audiences could play along with in the program of short subjects before the feature. These included animations and experimental montage-style superimpositions done by the brilliant German cinematographer Guido Seeber. I got all the answers right. Could you? (Actually, they’re very easy, as they would have to be in a theatrical situation.) The Blu-ray is regions A, B, and C. For more technical and historical background on the film, see Jan Christopher-Horak’s review of the Flicker Alley release. (It’s entry number 260; you’ll need to scroll down to find it.)

Leni continued on in the horror mode late in his career in Hollywood, making The Cat and the Canary (1927), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and The Last Warning (1928), all at Universal. These, along with the various films of Lon Chaney, notably The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1922) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), built the foundation for Universal’s famous horror films of the 1930s.

The Visual Music of Oskar Fischinger

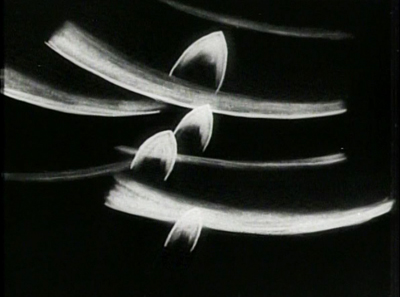

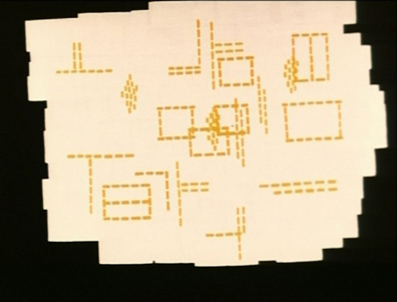

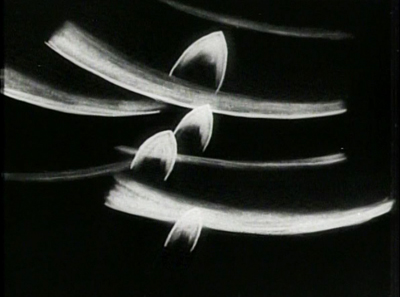

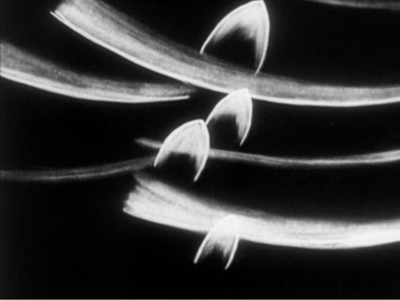

In my recent year-end entry “The Ten Best Films of … 1930,” I included Oskar Fischinger’s series of “Studies” from that year: short films of white shapes (drawn in charcoal on white paper and shown in negative) zipping around the screen in time to musical pieces. These run from Study No. 2 to Study No. 7, though others numbered up to 12 were made in 1931-32. Study No. 4 is apparently lost, and No. 1 is listed on the Fischinger Archive website (linked below) as having been accompanied by live organ music and never released on home video, while the subsequent ones were done with recorded music.

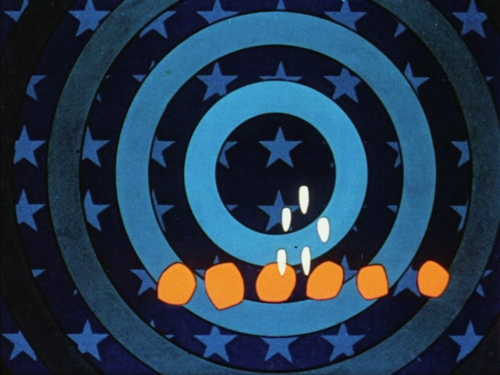

In that entry I linked to the Center for Visual Music as the sole source of two DVDs collecting Fischinger’s work. (I have discovered one other source. See the end of this entry.) At the time I had ordered them, and they subsequently have arrived. It was a great pleasure to sit down and watch both straight through. The films are delightful and lift the spirits. My viewing was on Inauguration Day, when my spirits were already quite lifted, and Fischinger’s An American March (1941), set to Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (above), was especially cheering on a day when our country got rid of a fake president and welcomed a real one.

Although Fischinger used both popular and classical pieces, he retained a similar, recognizable style for both. The black-and-white films were relatively simple, as in Study No. 6.

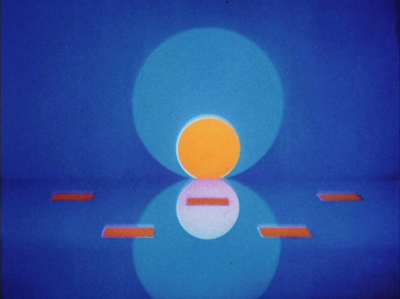

Like his contemporary, New Zealand animator Len Lye, Fischinger adopted color early and used the soft but extraordinarily vibrant Gaspar Color system. Most of his films of the 1930s employed it, as in Circles (at top) and Composition in Blue (1935).

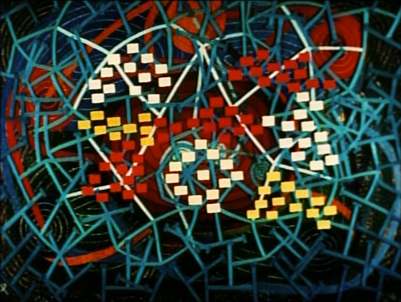

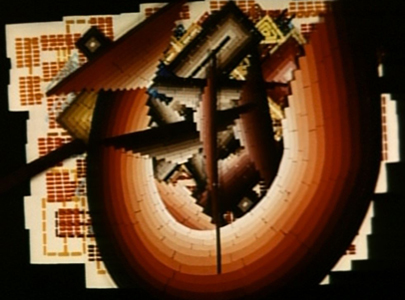

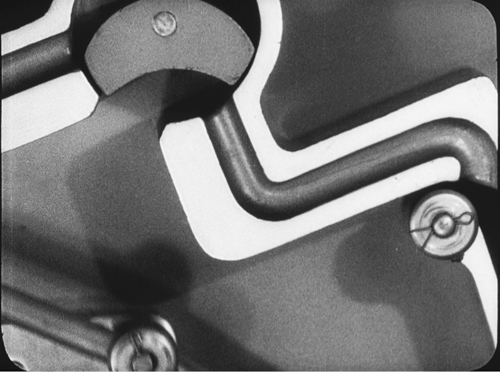

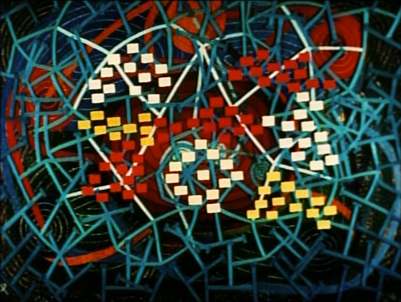

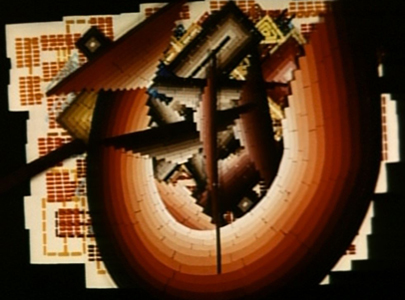

His masterpiece, at least in my opinion, is his last significant film, Motion Painting No. 1. It is his longest film at eleven minutes and is set to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3. It also departs from his usual modes of animation. Rather than substituting a new drawing or moving abstract shapes in space slightly between exposures, he added a brushstroke per frame, creating a continuously moving line that gradually created a series of compositions that changed the image completely as the line proceeded relentlessly and obliterated what went before. Thus across the film there is no pause in the line’s movement as it paints over its earlier progression. Here are some of the stages of its mutations. (Spoiler alert!)

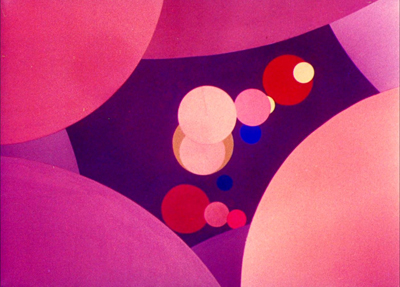

While these two discs contain nearly all of Fischinger’s important films, a conspicuous absence is An Optical Poem, which is an abstract animation of the usual sort made by Fischinger but for a major studio. MGM produced it as one of the seven-minute cartoons that were shown among the shorts in movie-theater programs for decades. Set to Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody Number 2,” it’s typical Fischinger, with lively colored discs and other shapes darting around. The main difference is that here he was working in Technicolor. As smaller discs pass behind larger ones, a distinct sense of depth is often achieved.

The reason for An Optical Poem‘s absence from the CVM discs is presumably because it is the only Fischinger film not controlled by the Estate. Fortunately the gap has been filled by its inclusion in Flicker Alley’s set, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970,” which I reviewed when it was released in 2015. Flicker Alley obtained permission from Warner Bros. and Turner Entertainment, which now control MGM’s library. This allowed them to include the original MGM logo and title, plus an introductory opening text that tries to prepare the audience for what’s to come. (These are missing from the prints posted online.)

Between the two CVM discs and the Flicker Alley set, we now have good copies of all but some minor, often unfinished works by Fischinger. The CVM discs do not contain much in the way of supplements, but one can get much more information from William Moritz’s Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger (2004). More information, including a bibliography of books and articles on the filmmaker, can be found on the website of CVM’s Fischinger Archive. Fischinger died in 1967, and several years later his wife Elfriede sent a collection of his equipment and the material used in his animated films to the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt. This collection included the plexiglass sheets upon which Motion Painting No. 1 was created.

Thanks to Lee Tsiantis for a correction to the Oskar Fischinger section!

January 27, 2021. Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for providing some additional information on the availability of Fischinger’s films. A number of art museums and specialty bookshops have sold the CVM DVDs in the past. The only place that is still doing so, as far as I can tell, is Walther Koenig‘s fine bookshop in Berlin. The CVM also has some excerpts and complete films on their Vimeo channel.

Posted in Animation, Covid-19 cinema, Experimental film, Film history, National cinemas: Germany |  open printable version

| Comments Off on German classics for the pandemic and beyond open printable version

| Comments Off on German classics for the pandemic and beyond

Tuesday | January 19, 2021

We have never reposted an entry before, but given recent events in US history, and the celebration of Martin Luther King’s legacy yesterday, and the impending inauguration of a new president tomorrow, we are re-running this entry, unrevised, from nearly four years ago.

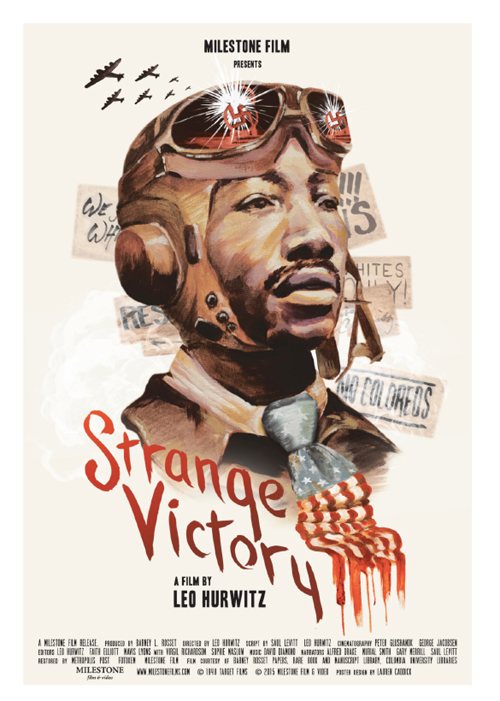

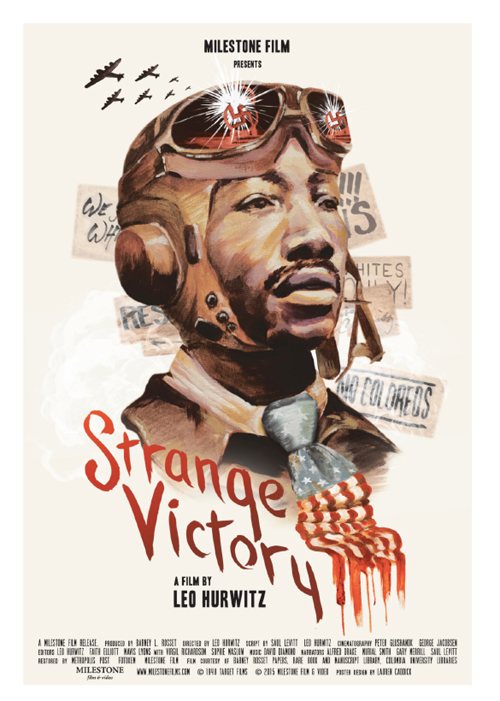

It’s not just that it remains timely. (The interpolations remind us that Trump has been inciting violence from the start.) We wanted also to note that thanks to Milestone Films you can stream Strange Victory here. I plan to write more about the end of the Trump era in the days to come, but for now we can acknowledge the struggles ahead of us. We can be strengthened by recognizing that in 1948 people who had sacrificed far more than we have still sustained an urge to fight for decency and justice. –DB

DB here:

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today. my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

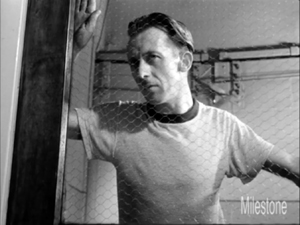

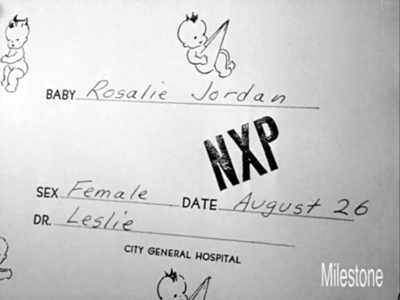

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.” Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

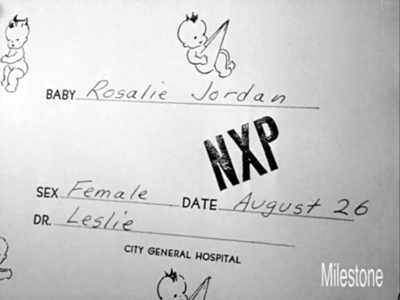

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.) 16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).

Posted in Documentary film, Film comments, Readers' Favorite Entries |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Repost: Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948) open printable version

| Comments Off on Repost: Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

Saturday | January 16, 2021

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

DB here:

Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Aaron Sorkin has carved out a unique position in contemporary Hollywood. If we want to understand craft practice from the position of media poetics—that is, the principles governing form, style, and theme in particular historical circumstances—we can usefully look at him as a powerful example.

He’s more than merely typical, of course. In an era when the f-word exchanges of Palm Springs pass muster as comic dialogue, it’s refreshing to watch a movie where smart characters, sparring for high stakes, make a retort that’s more stinging than a slap in the face. These movies are written through and through, and in distinctive ways.

More broadly, Sorkin’s distinctive career invites us to consider the nature of innovation and originality in the popular arts. Because of “progressive” accounts of art history, we’re inclined to emphasize the shock of the (utterly) new as the mainspring of change and the central source of quality. The history of modern painting is written as a series of breakthroughs after Post-Impressionism, from Cézanne through Picasso and Mondrian and so on—the leap to abandon the past, the “next logical step” in an advance toward…what? Abstract Expressionism? Then what? Similarly, from Wagner to Strauss to Schoebberg to Berg to Webern and then…? Boulez? And…?

If the history of an art is a surging procession of avant-gardes, what then do we do with the artists who don’t fit? There are eccentrics, such as Balthus or Satie, who turn out to “point forward” at angles and detours that the linear-progress story doesn’t allow. What about those artists who refine or revise tradition in fresh ways? Where do we put Deineka, recently noticed as no mere Socialist Realist hack, or Shostakovich and Sibelius? Or, in the orthodox history of the detective story (whodunits surpassed by hardboiled), Rex Stout?

In the popular arts particularly, we should expect to find historical patterns less like the Breakthrough Canon, a high-altitude survey of outsize rock formations, than something closer to the ground. Studying mass entertainments like film and popular fiction, we’re likely to find valleys revealing unexpected views of familiar landscapes. There are daisies in the crevices.

In contrast to the Breakthrough account, non-western art traditions valorize accumulation of options and preservation of precedent. An artist earns acclaim for finding fresh ways to realize long-standing craft principles. The Japanese renga poet, the Chinese painter or calligrapher, and the Ottoman carpet weaver revise inherited techniques to reveal new expressive possibilities. Actually, in the West we have the same situation. Come down from the bird’s-eye view, and we’ll see the same fine-grain fluctuations. E. H. Gombrich pointed out how painters, the masters and the minor players, develop their pictures on the basis of inherited patterns—schemas that they have learned and that provide a point of departure for original treatment.

In several places I’ve proposed that filmmakers work with schemas too—pictorial ones, but also narrative ones. The shot/reverse shot technique is a schema, but so is the framed flashback, the four-part plot, and the strategy of beginning your action at a point of crisis.

You see where I’m going with this. Sorkin is worth studying, I think, as a very skilled craftsman. Surveying just a few of his films showed me that he finds ingenious and sometimes powerful ways to rework the schemas from the tradition of American filmmaking—and, of course, from the theatre.

Ventilating the play

A Few Good Men (1992).

If you want to reach a broad audience in today’s American cinema, you need to either make films with large doses of physical action (as crossover indie directors have found) or to find a signature identity that cultivates a following. In Sorkin’s case, he has dared to rely on plot, dialogue, and a distinct worldview that he has managed to make entertaining. Sorkin’s first plays, followed by the huge stage success of A Few Good Men (1989), typed him as a “theatrical” talent. But over thirty years his film projects sought to “cinematize” what’s usually considered stage technique.

The obvious example is his reliance on “walk and talk,” the long backward tracking shot covering characters striding toward us and spitting out dialogue rapidly. This develops the verbal drama while also yielding some attention-grabbing visuals. But there are less apparent ways Sorkin has blended theatrical technique and cinematic narration.

Early twentieth-century playwrights tended to put the “point of attack”–the moment in the story when you start the play’s plot–fairly close to the climax. Associated with Ibsen and other pioneers of “new theatre,” the late point of attack was a solid convention by the 1910s. As in A Doll’s House and Ghosts, the action starts at a point of crisis, and offstage events leading up to it get revealed through dialogue, sometimes called “continuous exposition.”

The trial schema is a good example of the crisis structure. Typically a trial starts after a lot of stuff has already happened, so the continuous exposition is supplied through testimony and speeches by the defense and prosecution. By 1915, Elmer Rice’s play On Trial was inserting flashbacks that reenacted trial testimony, but some plays stick only to what happens in the courtroom. The Off-Broadway production of A Few Good Men used that linear, present-tense premise, in the vein of earlier plays like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1954) and Inherit the Wind (1955). The investigation of the death of a young Marine is pursued by a prosecution team running up against the military code and a couple of hard-headed officers.

But in preparing the film version, Sorkin adapted to the menu of storytelling options on offer in 1990s moviemaking. For instance, the opening scene could be a grabber, a strong moment that aroused curiosity or suspense. (This might have been a reaction to the need to grab the viewer who’d later see the movie on cable or video.) So instead of letting everything be recounted in the trial, Sorkin’s screenplay for A Few Good Men chose an earlier moment in the story action–a literal “point of attack” showing Dawson and Downey assaulting Santiago.

Later, Sorkin ventilates the play in a traditional manner, supplying scenes that present the prosecutors taking the case and investigating the circumstances. The courtroom scenes don’t begin until about an hour into the film, and they alternate with strategy sessions among the legal team and the defendants. The result is a “moving spotlight” narration, mostly attached to Kaffee the lead prosecutor and Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway, but ready to shift to other characters.

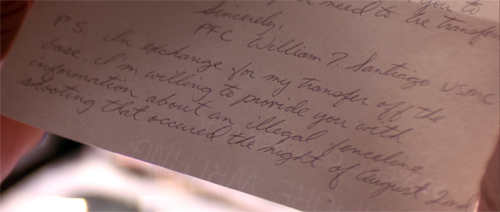

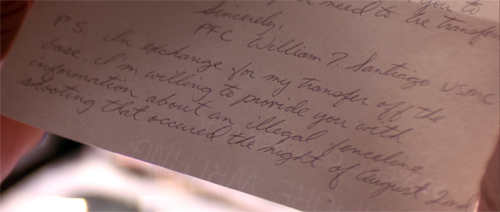

The timeline is chronological, except for a brief flashback dramatizing a letter initially voiced by Santiago. He appeals to Colonel Jessep to transfer him out of the unit for medical reasons. In exchange he offers to give information about an illicit fence-line shooting.

The flashback modulates to Jessep reading the letter aloud (an audio hook) and considering how to handle the situation.

This narration, shifting us from one group of characters to another, gives us a glimpse of the hidden story that the prosecutors need to uncover. The question will become not whether the officers overstepped their authority, but how they will be caught.

After A Few Good Men, we can see Sorkin’s cinematic career as exploring the creative space opened up in the 1990s, a space I’ve tried to map in The Way Hollywood Tells It and several blog entries. For one thing, there’s the matter of how to pick a protagonist.

It seems to me that the film version of A Few Good Men makes Kaffee the protagonist, with Joanne and Sam Weinberg as helpers–just as Jessep is the ultimate antagonist, with Kendrick as his helper. Centering on Kaffee and making him a gifted but glib and cocky young lawyer fits Cruise’s emerging star persona (Top Gun and The Color of Money of 1986, Cocktail of 1988). Sorkin has given us other single-protagonist plots, such as Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Moneyball (2011), and Steve Jobs (2015).

We may identify Sorkin more with ensemble, or multiple-protagonist, plots because of the fame of his TV shows Sports Night (1998-2000), The West Wing (1999–2006), Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006–2007), and Newsroom (2014-1016). A long-form series permits constant shifting of the protagonist role across a season. But in feature films, I think, a genuine equality among several protagonists is more common in “network narratives” than in crowded films like The Women (1939) and Ocean’s 11 (2001). In the latter, there tends to be a “first among equals”: one or two main characters whose fates are most important, even if subplots centering on others are woven in. Such is the case, I’ll argue, with The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Scanning the menu

Molly’s Game (2017).

Sorkin’s preferred artistic strategies emerge even more clearly, I think, in his handling of narrative structure. He has more or less systematically surveyed a range of storytelling possibilities.

Politically liberal but narratively conservative, The American President (1995) presents an utterly linear plot. As in other romantic comedies, the central couple shares the protagonist role. Their relationships change as they make decisions and respond to external forces. The film plays out the familiar Hollywood double plotline of love versus work: political pragmatism threatens the President’s affair with a lobbyist for environmental reform. There are no flashbacks or fancy time-juggling, and the dialogue is classic flirtation, wisecrack, and one-upsmanship. The one “Fuck you!” becomes a shocking turning point, a test of friendship.

The crisis structure in The American President is presented as a race against time to line up support for two White House bills. Moneyball (2011) creates a comparable pressure on its protagonist. After his baseball team’s loss and the departure of his top players, Billy Beane faces the need to rebuild his roster for the new season. In a classic problem/solution plot layout, he finds a helper in statistician Peter Brand. Again, the plot is mostly linear, though interspersed with summary montages of sports coverage and brief flashbacks to Billy’s own failed ballplaying career.

The fragmentary flashback that carries its own mystery was a common technique of 1990s cinema (e.g., The Fugitive) and remains a standard tool of filmic storytelling. Sorkin’s films use it often, usually to gradually reveals what’s driving the protagonist’s struggle. A version of “continuous exposition,” the flashback allows deeper character revelation; it can liven up the more static sections of the film; and it can provide its own little mystery revelation. In the Moneyball flashbacks we see Billy recruited, decide to give up a college career, and then face failure. This shows how he could have empathy for the second-tier players who are cast aside–and whom Brand’s moneyball algorithms give a second chance.

The time structure is a little more complicated in Charlie Wilson’s War. Here Sorkin samples another option in the schema menu. The story’s crisis is over; the plot starts at the epilogue. After a credits-sequence montage, we’re taken to a CIA awards ceremony, at which Charlie Wilson is honored for working strenuously against the USSR for thirteen years. This scene turns out to be a frame around an extensive flashback.

What follows deflates this high-flown tribute, as we go back to 1980 and see the reprobate congressman pressured into helping the Afghan people by finagling clandestine US investment in fighting the occupying Soviet troops. Other subplots, including an investigation of Charlie’s partying ways, are interwoven. The long flashback concludes and the film’s final sequence returns to the ceremony, with a replay of a grinning Charlie getting his award. The ABA structure makes the whole public event a charade, underscored by a final title: “And then we fucked up the endgame.”

By contrast, Molly’s Game is more fragmentary. We start with a teenage Molly Bloom in a skiing competition qualifying for the Olympics, but an accident knocks her out of the running. This early passage is in turn interrupted by brief flashbacks to earlier in her childhood, of other competitions and accidents and recoveries, overseen by her demanding father. Her first-person voice-over fills in the background, echoing the fact that the story is drawn from the book she’s written (both in real life and in the film).

“None of this has anything to do with poker,” a title ironically informs us, but it’s a tease. This prologue, mixing scenes from phases of Molly’s girlhood, characterizes her as having tenacity, determination, and not a little rage at her dad. Then the present-day action starts, as usual at a crisis. Molly is wakened from sleep by the FBI arresting her for illegal gambling. What has happened in the meantime? Even after the scene of her arrest, the film’s narration wedges in a VHS interview with young Molly in which she’s asked about her goals.

The revelation of the formative years, saved for late in Moneyball, is put up front in Molly’s Game. But now there’s a mystery: How does a promising athlete become a gambling queen?

The question is answered through another series of time shifts, and these occupy the bulk of the film. After Molly’s arrest, the narration fills in her arrival in Los Angeles and her job working for a sleazy entrepreneur who arranges poker games for rich men. Her rise in the world of underground gambling is intercut with present-time scenes of her consulting an attorney to take her case–a risky proposition, since her customers include Russian mafia. And the alternation of her legal problems and her gambling career continue to be interrupted by flashbacks to her as a little girl, as a teenager, and as witness to her father’s infidelities.

Sorkin has layered his plot within several time zones: present, immediate past, and distant past, with the earliest one including scenes scrambled out of chronological order. Again, the purpose is to reveal character motivation. The flashbacks suggest sources of Molly’s decision to triumph over weak men–perhaps, it’s suggested, as revenge for her father’s mistreatment of her and her mother. The time jumps also reveal her as a fierce competitor unwilling to give in. Athletics, it turns out, has a lot to do with poker.

The network as character prism

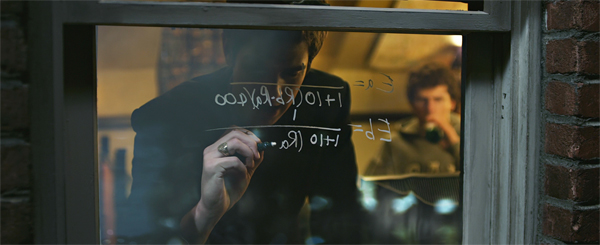

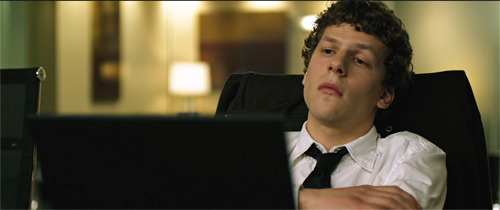

The Social Network (2010).

If there were a simple progress in Sorkin’s exploration of the menu of options, you’d expect that The Social Network would come later than it does. Yet before Molly’s Game yielded three principal time layers (the legal case, the career rise, the girlhood), Sorkin’s screenplay tracing the rise of Facebook had already fielded something more complicated than that.

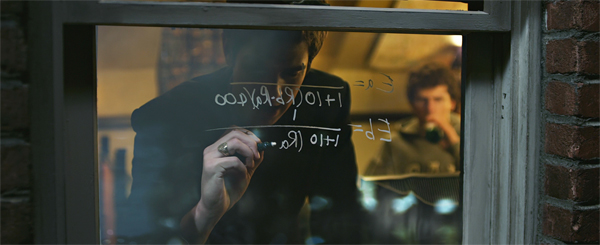

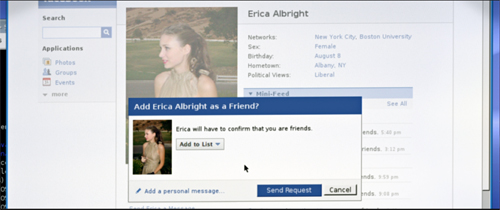

Still trying variants, Sorkin this time puts the motivating moment, the incident that drives the character, at the front of the film. In 2003, Mark Zuckerberg is on a date with Erica Albright. His arrogance provokes her to break up with him. In a burst of pique, he turns a blog into a page that denounces her and asks readers to rate local women. With the reluctant help of his friend Eduardo Savarin, the site crashes the Harvard server and Mark faces disciplinary action.

At this point the film splits into more time-tracks, again transmitted through legal proceedings. The Harvard disciplinary hearing is filtered through a deposition responding to Eduardo’s lawsuit against Mark, long after their partnership has collapsed. Sorkin could have picked this testimony as his point of attack for opening the film, then flashed back to the origins of the suit. Instead, like Molly’s Game, The Social Network starts its plot in the past, skips ahead to the future, and then fills in more of the past.

A second lawsuit is in progress, this time from the Winklevoss twins, and a second string of deposition scenes. Apparently more or less simultaneous with the Eduardo sessions, these also anchor us in an approximate present and cue up incidents in the past. For instance, in a past scene, after an ally of the twins tells of Mark’s successful webpage, the narration cuts to the opening of the Winklevoss case’s depositions, and then back to the brothers recruiting Mark to work on their project.

The dual-track depositions in the present allow Sorkin not only to segue into illustrative scenes in the past, but also to set up crosstalk between the two lawsuits. Immediately after Mark dodges questions from the Winklevii, we see him dodge questions in Eduardo’s session.

By the 2000s, audiences trained in the time-shifting of the 1990s could follow these quick alternations. It’s also up to the director to keep us oriented through differences in costume, angle, lighting, color design, and other elements.

If you take the opening portion as what sets the narrative Now, you could call the deposition scenes flashforwards. Alternatively, you might consider those scenes as Now, although the opening orientation to them has been deleted. Either way, Sorkin has provided a flexible, dynamic structure that allows us to study Mark’s behavior and others’ responses to it.

One of the dreams of storytellers who embraced multiple-viewpoint plots was the idea of letting us see different, even contradictory facets of a character. The prospect was broached by Henry James (in his novel The Awkward Age) and Joseph Conrad (in Lord Jim, Chance, and other books). On the stage, Sophie Treadwell had experimented with it in The Eye of the Beholder (1919). Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles played with the possibility of such a “prismatic” narration in Citizen Kane, perhaps as a result of Mankiewicz’s unproduced play about John Dillinger.

By using the trial schema a storyteller can present a character’s public self-presentation, the impression management that tries to win adherence. But the fact that different people testify about a situation also offers prismatic possibilities. Here, the chief contrast is between Mark’s snotty recalcitrance at the counsel table and his swagger in the past.

During the film’s opening, when Mark confides in Erica and Eduardo, we’re about as close to penetrating his mind as we’ll get in the film. Later the film’s narration offers less a study in how his mind works than a portrait of how he handles people–his social survival strategies. The range runs from sheer bluster, as when he tries to overwhelm Erica, through awkward acceptance of class ambition when he meets the Winkleviii, to evasion, threats, and bumbling efforts at friendship. At the end, he goes flat and legalistic, telling Eduardo: “You signed the papers.” The film’s denouement arrives when Eduardo’s lawsuit is launched. “Lawyer up, asshole.”

The opening sections began in the past, but the ending leaves us hanging in the present. At a pause in Eduardo’s suit, the film concludes on the image of blank-faced Mark staring at his monitor. Isolated by his betrayal of the one person close enough to have been a friend, he’s checking Erica’s Facebook page.

This conclusion lets us imagine that sexual and romantic frustration, exposed in the opening, have reinforced Mark’s low-affect aggressiveness. It’s also a suggestion that his slightly vampirish predation suits him for the age of the social network. But we’ll never be sure, because his disdainful indifference is his armor against everyone he encounters.

As with Molly’s Game, this cluster of parallel timelines is intelligible and forceful as a revision of a schema (present/ past/ present) that we know well. And careful cutting, sound work, and performance have kept us on track throughout.

End to end control

Steve Jobs (2015).

In films that don’t rely on chases, fights, explosions, time travel, fantasy, or extraterrestrials, what can hold your interest? For one thing, snappy talk. The old theatre adage claims that dialogue needs to do one of three things: advance the action, delineate the characters, or add humor. Sorkin’s dialogue does all of them at once.

Steve Jobs is braced by his assistant Joanna while he frets over a press story.

“’The only thing Apple’s providing now is leadership in colors.’”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“What does Bill Gates have against me?”

“I don’t know, you’re both out of your minds. Listen to me–”

“He dropped out of a better school than I dropped out of . . . but he is a tool bag and I’ll tell you why.”

“Make everything all right with Lisa.”

“You know–Joanna–boundaries.”

“You’ve come to my apartment at 1 AM and cleaned it, so tell me where the boundary is.”

“There, let’s say it’s there.”

“If I give you some real projections, will you promise not to repeat them from the stage?”

“What do you mean real projections? What have you been giving me?”

“Conservative projections.”

“Marketing’s been lying to me?”

“We’ve been managing expectations so that you don’t not.”

“What are the real projections?”

“We’re going to sell a million units in the first ninety days. Twenty thousand a month after that.”

Each reply shows that a strong line is like an arrow–feathered at the top, barbed at the tip. If your conflict is psychological, then the last part of the line should land with a punch. “We’ve been managing expectations so you don’t not.”

But the lines don’t exist in isolation. Every stretch of the film is a vivid lesson in whipping together bits of earlier conflicts, jumping from one to another as Jobs parries and ducks and changes the subject, all the while tension rises. One issue is picked up (Steve’s reaction to press coverage), interrupted by others (his rivalry with Gates, his friction with his daughter), followed up by a long-running relation with Joanna (“boundaries”), then a big piece of information: one goal, a sales target set in the first segment, has been achieved. But the others are left dangling, to be revisited, and we are looking forward to that.

This sort of repartee brings back the era of snappy chatter. The exchanges recall the films set in rehearsal halls (Footlight Parade), news offices (His Girl Friday), movie studios (Boy Meets Girl), gangster cafes (All Through the Night), and even a research institute (Ball of Fire). A few films of recent years, such as The Paper, successfully recapture the exhilaration of such fast, pungent dialogue. Sorkin delivers it consistently.

Steve Jobs is one of Sorkin’s most structurally ambitious projects. Here he tries out another menu item, that of block construction. In this layout, we get two or more marked-off chunks or chapters, sometimes without the same characters. Block construction came into fashion with Mystery Train (1989), Slacker (1990), and other indie works, and it remains a basic resource for Tarantino and Wes Anderson.

As ever, Sorkin rewrites the block premise as a drama convention, the division into spatially and temporally confined acts. The plot of Steve Jobs is organized around three public product launches: in 1984 (the Macintosh), 1988 (the NeXT Black Cube), and 1998 (the iMac). Each event teems with crises large and small, public and private. They’re all parallel, in that we see the few minutes of preparation leading up to the curtain-raising. Like a party or restaurant scene in a play, a product launch offers a confined space in which characters and story lines can mingle. The pressure of a product demo allows Sorkin to create deadlines and motivate many walk-and-talk passages through backstage corridors.

Just as theatrical is the flow of people into and out of Steve’s presence. From act to act the same associates are ushered into Steve’s presence: his former romantic partner Chrisann, his business partner Steve Wozniak, John Sculley, engineer Andy Hertzfeld, a journalist, and Lisa, the daughter that Steve is reluctant to acknowledge. The French phrase liaison des scènes, “scene linkage,” captures the way that within a single setting characters’ entrances and exits break the act into distinct pieces.

In addition, Sorkin doesn’t confine his time frame to the duration of the demos. As in other films, flashbacks interrupt the present. The 1984 segment uses only one flashback, a visit to garage-hacking days that sets up the dispute about open and close architecture. The flashbacks thicken in the second segment, which reveals the conflict that led Steve to break off with Sculley. That quarrel in the past is tightly crosscut with their confrontation in the present, and as the tension builds one man in the present is replying to an objection in the past. This rapid pacing is one way a “theatrical” premise can hold an audience accustomed to action movies.

Like Fincher’s intercut depositions in The Social Network, Danny Boyle’s handling keeps us oriented through staging, costume, color, lighting, and shot/ reverse shot eyelines.

The block most saturated with flashbacks is the third, the one launching the computer that brought Apple to marketplace triumph. This chapter incorporates glimpses of scenes shown in the first two segments, along with revelations of Steve’s first approach to Sculley. This last recollection is prompted by his admission that he long ago found the biological father who gave him up for adoption. (Many of Sorkin’s protagonists have Daddy Issues.) Again, a big revelation about character motivation is saved for a flashback late in the film.

In addition, other crises come to a head. Steve appears to break definitively with Wozniak, and he reconciles with Lisa, whom he hasn’t, after all these years, fully taken into his life. As he achieves his goals–a successful computer at last, a settling with Wozniak and Andy, and a tentative accceptance of Lisa–he displays more chastened and cautious behavior. He has admitted his fallibility (he was wrong about the Time cover), he has realized what he lost in challenging and trashing Sculley, and he’s ready to move to the next challenge (“music in your pocket”). True, he treats Woz brutally, but Woz gets the final word: “It’s not binary. You can be gifted and decent at the same time.” Steve doesn’t change completely; he just gets a bit more human.

Interestingly, these cadences fit the four-part structure that Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood has revealed governing many classical plots: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax, followed by an epilogue or tag. Sorkin has “cinematized” his three “acts” by letting the final one harbor Development, Climax, and an epilogue.

Kristin also points out that classical film story telling relies on motifs that weave their way through the film. Not only music but lines of dialogue and images recur to point up repeated actions, indicate changes in character, or add humor. (A running gag is a comic motif.) Yet movies didn’t invent this tactic. Novels, poems, and plays rely on recurring motifs. Macbeth circulates imagery of blood and ill-fitting garments, while The Importance of Being Earnest wrings a lot out of the mysterious word “Bunbury.”

Steve Jobs is packed with motifs, far more than most movies I can think of. Some bounce around one segment and into another, and several come back at intervals in all three. All the characters relitigate old complaints, and Steve masterfully deflects a conversation by returning to remarks he’s made before. Here’s a partial list of items that are recycled again and again.

Starting exactly on time, the controversial SuperBowl ad, the need to turn off the Exit signs, a bottle of ’55 Margot, the Time cover, the purported treachery of Dan Kottke, “a million in the first 90 days,” “I don’t have a daughter,” 28%, Woz’s request to acknowledge the Apple II, “playing the orchestra,” closed versus open systems, the name Lisa, “end to end control,” 2001, “a dent in the universe,” slots, Pepsi, the psychology of adopted kids, “You get a pass,” the threat of a press release, and “which Andy?”

For Sorkin, even “Fuck you” becomes a motif rather than a space-filler.

A significant cluster involves the arts, particularly music and painting. In their quarrel the two Steves compare themselves to the Beatles, and Bob Dylan’s image and songs float through the movie. This association with the arts helps offset the unpleasant side of Jobs’ temperament, his crisp, frosty bullying of others and his relentless imposition of his “reality distortion field.”

Another motif softens him a bit: his desire to bring computing to kids. The prologue, in which Arthur C. Clarke is interviewed about the future of computing, sets up several motifs–the idea of separating oneself from others (Steve in a nutshell), the importance of home (associated with Chrisann’s demands), and particularly childhood. The reporter interviewing Clarke has brought his boy along, and they discuss how a new generation will quickly grasp the power of personal computing.

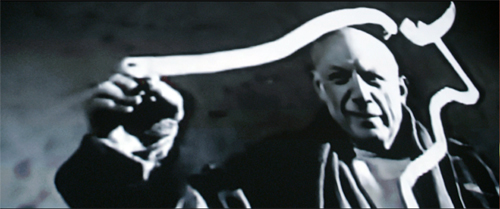

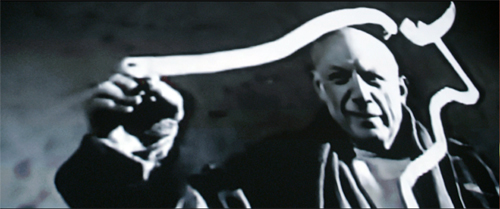

That motif is dramatized when, at first indifferent to five-year-old Lisa, Steve uses her as a demo to show Chrisann what the Mac can do. But his interest rises when Lisa intuitively understands that she can draw with it. “Lisa made a painting on the Mac,” he says thoughtfully. He seems to realize that she could be his brainy daughter, and he resolves to put her in a good school. Her drawing looks forward to Picasso’s swooping dab at a bull in the climactic montage of the 1998 launch.

The ping-ponging motifs are mostly in the dialogue, though. They push the action forward, recall earlier moments, and characterize the combatants while also yielding some laughs. Above all, the motifs chart Jobs’ character arc. We know that he’s more committed to Lisa at the end when he breaks his routine and says he’s willing to start the performance late. Soon he will reveal that he has saved her painting to give to her.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I call Jerry Maguire a “hyperclassical” movie–more classical than it needs to be, flaunting a virtuosity of construction and motivic echo. I vote for Steve Jobs as another instance. Sorkin has used cinema to multiply motifs to a higher power.

Exporting ideas across state lines

The Trial of the Chicago 7.

One innovation of turn-the-century-theatre was the so-called “drama of ideas” or “problem play.” Ibsen, John Galsworthy, and Bernard Shaw sought to break away from standard intrigues of mystery and romance in order to dramatize women’s rights, labor struggles, and other social issues. Sorkin, with his liberal political bent, has brought that legacy to his film work. The subjects and themes he tackles have become as distinctive a marker of his work as any strategies of form and style.To be more precise, his formal and stylistic strategies work upon the ideas he wants to put forth.

How much private life is a US President entitled to? What is the duty of a politician who wants to enact social change? For a tech entrepreneur, where does idealism end and domination begin? Why should a woman not be able to compete on equal terms with men? Does social change come best through reform (reason, the ballot box) or revolution (change of consciousness)? Something like this last occupies him in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

The problem at the center of the film is: How to protest, and eventually stop, US involvement in the Vietnam war? The film’s prologue and epilogue announce the sweep of the issue. It begins with President Johnson ramping up troop commitments and establishing the draft lottery, all during a wave of assassinations. The film ends with Tom Hayden reading out the names of troops who have died while the trial was dragging on. Early on, Rennie Davis establishes the list because it’s “who this is about.”

The defendants in the trial are only loosely associated. Bobby Seale doesn’t know the others and was in Chicago just four hours; he’s also denied counsel. Sorkin carves out two major factions. Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis, as student activists out of SDS, are presented as preppy intellectuals, committed to antiwar action within the frame of protest and legal debate. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, associated with the Yippies, are countercultural provocateurs. They anticipate a spectacle of innocence attacked by those in power. They will show the Chicago Democratic convention to be staged, as Walter Cronkite says at the end of the opening montage, in “a police state.”

Although Tom’s and Abbie’s factions communicate a little before the events, it’s the pressure of circumstances in Grant Park that pushes them into dispute. Alongside them Sorkin develops subplots that suggest other political alignments. David Dellenger’s commitment to nonviolence is tested by the flagrant repression of Bobby Seale. Richard Schultz goes along with orders to prosecute, knowing that the case is trumped up. Jerry Rubin falls briefly in love with an undercover policewoman. Fred Hampton tries to help Seale, only to be killed. Attorney William Kunstler discovers that he has a surprise witness to call. Editor Richard Baumgarten notes that in cutting all these lines of action together: “I feel like one of the great successes of how this film unfolds is that each of the characters does have a moment, or multiple moments.”

Tom and Abbie emerge as the “first among equals” because they most sharply articulate alternative accounts of what they’re facing. They aren’t dual protagonists, like a romantic couple tackling common problems. They’re at odds throughout. On the first day when Tom tries to get agreement on goals, Abbie challenges him.

Early court scenes show Tom annoyed by Abbie’s antics, but neither is really an antagonist for the other. Tom can half-humorously admit that he got a haircut to impress the judge, and clearly Abbie admires Tom. The antagonists are the government prosecutors and Judge Hoffman. Tom and Abbie function as what Kristin calls parallel protagonists. Like Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus, or Captain Ramius and Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October, they are at once opposed to one another and fascinated by each other. They both compete and cooperate.

What does each one want? This will become part of the drama’s problem, because the two men will be charged with coming to Chicago to stir up violence. Sorkin shrewdly postpones the question in the opening montage that brings some main players together through crosscutting. Incomplete dialogue hooks make their goals somewhat mysterious.

Tom: Young people will go to Chicago to show our solidarity, to show our disgust, but most importantly–

Abbie: –to get laid by someone you just met. . . .We’re going peacefully, but if we’re met there with violence, you better believe we’re gonna meet that violence with–

Dellenger: –non-violence. Always non-violence and that’s without exception. . . . (asking his son what to do in the face of police:)

Dellenger’s son: Very calmly and very politely–

Bobby Seale: –Fuck the motherfuckers up!

Seale’s capper would seem to negate the nonviolence of Dellenger’s position, but at the end of the montage Bobby refuses the pistol his colleague Sandra offers him. “If I knew how to use that, I wouldn’t need to make speeches.”

Unlike Dellenger, he’ll hit back if attacked first. So now only the positions of Tom and Abbie remain undefined.

Eventually, Tom exposes his rationale. If they can prove they were peaceful demonstrators within their rights, it will help “to end the war and not fuck around.” That demands treating the trial seriously. “We as a generation are serious people.” And he doesn’t want to raise police culpability. “We’re protesting the war, not the cops.”

From the start Abbie insists that the trial isn’t a matter of law but of contingency. “This is a political trial.” They were chosen to be examples, and the two lesser defendants are “give-backs,” people the jury can let off with a clear conscience. Abbie and Jerry came to Chicago knowing that police violence was very likely. (Cronkite said so too.) The best way to prove state oppression is to lay it bare, preferably with gonzo humor. After all, the whole world is watching.

The film’s structure supports Abbie’s analysis. Sorkin’s narration, using a moving-spotlight approach, has from the start tipped us that Attorney General John Mitchell has ordered Schultz to prosecute the 7 on flimsy grounds. Mitchell, a spiteful conservative, wants to crush antiwar protest, but he’s also petty. He’s miffed that Johnson’s AG Ramsey Clark insulted him on the way out of office. Mitchell has assembled a mixed bag of antiwar activists to charge with conspiracy. (In an ironic twist, they conspire most successfully after they have been thrown together for trial.)

So the problem play becomes a progress toward understanding political power. Tom Hayden (and to a lesser degree Kunstler) come to grasp the reality of an engineered police provocation and a show trial. Abbie’s privileged insight is further stressed by the fact that he’s the only character given a narrator role. Sorkin interrupts the trial with shots of Abbie at a mike in a club, telling the story of the fights during the riots, correcting the false testimony of the cops. In stage tradition, Abbie is the raisonneur, the explainer.

The conflict between Tom and Abbie gets specified gradually, sharpened in strategy sessions where Tom berates the Yippie contingent for clowning. If progressive politics is branded as childishness, “We’ll lose elections.” Abbie calmly replies that “We’re going to jail for who we are.” The debates are about tactics as well. Tom wants the demonstration to keep away from the convention hall, while Abbie insists that they go downtown. As it turns out, the police squeeze them out of the park and force them into a trap that yields the spectacle that Abbie and Jerry anticipated.

Through crosscutting Sorkin again creates several layers of time: the runup to the convention, the protests themselves, the trial, and a more unspecified moment when Abbie is at the microphone narrating. More linear than the time mosaics of Molly’s Game and Steve Jobs, the Chicago 7 array might seem a step back toward the classic trial schema. Basically, the court proceedings frame the flashbacks to the purported crimes.

The relative linearity is needed, however, to allow us to chart the progress of the parallel protagonists. In a neat balancing act, Sorkin dramatizes character change with Tom Hayden and character revelation with Abbie Hoffman.

Hayden’s character arc traces his realization that the trial is rigged. He has brought table manners to a revolution. He presents a wholesome appearance, and when pressed by Bobby he half-admits he’s rebelling against his upbringing. (Daddy Issues again.) Even his “reflex” action of rising when His Honor enters, violating the pact among the 7, shows that the impulse to behave well is struggling against his sincere urge to end the war through citizen action.

Yet Tom has an outlaw side as well. He releases the air from the tire of a cop car to allow Rennie to escape surveillance. At the climax, seeing Rennie beaten, he calls for blood to flow through the city–not, he tries to explain, the blood of others, but the blood freely given by the protesters. Still, he joins forces with Abbie, Jerry, and Dellenger as they are lured onto the footbridge and into the cops’ trap. The cops, having choreographed the street assembly, push them through the tavern window.

Tom, our main viewpoint vessel in the film, also visits Ramsey Clark with his attorneys. It’s then that he realizes the trial is Mitchell’s political charade aiming to override Clark’s decision not to prosecute the demonstrators. So, after Clark has testified (and sees his testimony suppressed by Judge Hoffman), Tom can redeem himself.

Judge Hoffman has offered Tom clemency before he makes his final statement. The good boy who had asked, “Why antagonize the judge?” rises in polite defiance to read the names of the dead. He will take the same punishment meted out to the others. He now understands revolution as spectacle.

So there’s a little of Abbie in Tom. In the same final stretches of the film, we learn that there’s a little of Tom in Abbie. Tom had planned to testify, but he can’t justify what he said on tape. So Abbie takes the stand. His slapstick persona drops. Behind the Jewish Afro and the wisecracks is revealed an intellectual who can quote the New Testament and gently praise Tom as a patriot. Schultz questions him: Was he hoping for a confrontation with the police? “I’ve never been on trial for my thoughts before.”

As in the opening montage, Sorkin cuts away before Abbie answers, and his pause and grave demeanor let us consider that for all his bravado, he has regrets about the crisis he saw coming.

Like any problem play, The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be criticized for stacking the deck, or oversimplifying, or recasting the problem in ways that favor certain interests (e.g., white college-educated men). But that critique is the risk artists run all the time, even in the most anodyne “nonpolitical” work. If critics study how films achieve their effects, viewers can be more aware of how the schemas we know are shaped by the movies we see and get a clearer sense of means and ends, purposes and fulfillment.

At the same time, artisanal skill in a robust tradition is intrinsically worth analysis. That analysis can reveal new possibilities in what cinema can do. In The Trial of the Chicago 7 Sorkin creates a dramaturgy that embodies ideas in characters’ conflicts, changes, and hidden facets. Once more a theatrical premise has been turned into classically constructed cinema. Sorkin’s work offers one way that this tradition can stay fresh–not through shocking breakthroughs but by highly skilled reworking of schemas accessible to a broad audience. You know, the way theatre used to be.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin and Jeff Smith, who helped me clarify my ideas.

For more background on this sort of narrative analysis, there’s a synoptic blog entry here. This earlier one might also be of use. Rory Kelly offers some nuanced analysis of the Hollywood character arc.

Cinema’s debts to theatre are considered in this entry, and some others in the category Film and other media. On the power of artisanal care, there’s this on Buster Scruggs.

Another entry discusses how actors use their faces in The Social Network.

P. S. 5 March 2021: I’ve just found some interesting remarks from Sorkin about what he calls “the puppy crate”–the need to focus a drama in a confined time and space. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is an obvious example, but so too is Steve Jobs. “I need four walls really badly.”

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

Posted in Directors: Sorkin, Film and other media, Film technique: Screenwriting, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Narrative strategies, Poetics of cinema |  open printable version

| Comments Off on THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu open printable version

| Comments Off on THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu

Monday | December 28, 2020

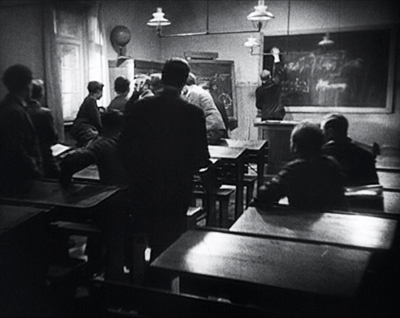

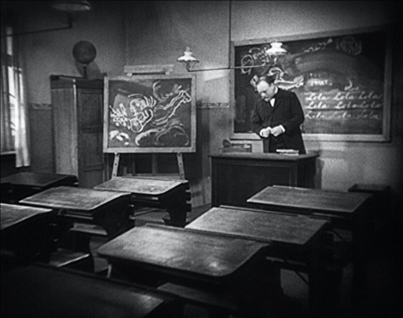

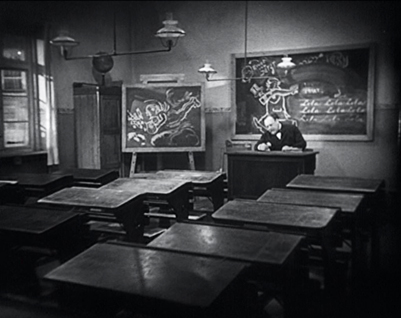

The Blue Angel (1930)

Kristin here:

The end of this horrendous year is fast approaching, though we are still facing a long struggle to end the pandemic. On a happier note, it is also time for a little distraction in the form of my annual year-end round-up of the ten best films of ninety years ago. 1930 was also a grim year, with the Depression well established and nowhere close to its end. Herbert Hoover decided not to use federal governmental powers to help end the crisis (sound familiar?) and eventually was cashiered into a 32-year retirement, though he continued to oppose Roosevelt’s policies. At least we don’t face that long a stretch of down time with the current “president.”

I discovered that 1930 did not produce many masterpieces. There are some obvious titles on my final list, as always, but some of the films are good but not great. In any other year they would not have made the cut. (The contrast with 1927, for example, is pretty stark.) Presumably one major reason is that filmmakers were still struggling with the introduction of sound. Fritz Lang didn’t release a film that year, though he came roaring back with M in 1931, as assured a treatment of sound cinema as one could find during those early days. (For those of you who subscribe to The Criterion Channel, I contributed a video essay on sound in M to David’s, Jeff Smith’s, and my series, also called “Observations on Film Art.”) Eisenstein was off in Hollywood unsuccessfully trying to make a film for Paramount and about to fall in love with Mexico. With one notable exception, Hollywood’s important auteurs made no films or minor films or films that don’t survive.

This dearth of really great films will be short-lived. From 1932 on, I shall no doubt have the opposite problem. For now, here are my picks. All the films are worth seeing, though good copies or even any copies of some are hard to track down. (The idea that all films are available to stream online is as absurd as when, back in 2007 when I wrote “The Celestial Multiplex.”) Some of my illustrations in this entry are subpar, but 1930 does not seem to be a year that studios and home-video companies are mining for titles to restore. I hope this entry will give them a few ideas.

I try not to include more than one film by the same director in these entries, aiming for variety and coverage. This year’s most prolific great directors were Josef von Sternberg and Yasujiro Ozu, who together could have filled in half the ten slots, but I have stuck to my guideline. (When we reach 1932 and 1933, I may be tempted to make an exception for Ozu.)

Given that sound developed at a different pace in different countries, some of this year’s films are silent.

For previous 90-year-ago lists, see 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928 and 1929.

Dovzhenko’s Earth

Some of the films on my top-ten list this year may raise eyebrows, but Earth is probably my least controversial choice. It remains one of the last classics of the Soviet Montage movement.

The policy of merging small farms into collective ones had begun in 1927 as part of the First Five-Year Plan. In 1929-30, the push increased, with the seizure of the assets of the more prosperous peasants who resisted collectivization, termed kulaks. Major films were made with the aim of villainizing the kulaks and emphasizing the backbreaking labor involved in traditional, non-mechanized farming. Eager young peasants were hailed as heroes, and tractors appeared as the means to greatly increase wheat yields–wheat which was often seized and sent to the cities to enable rapid industrialization.

Eisenstein had promoted collectivization with his Old and New in 1929, and Dovzhenko followed a year later with Earth. While Eisenstein’s approach had been sarcastic and comic, Dovzhenko pursued his poetic approach to cinema. The opening celebrates the fecundity of the earth and the cycles of nature. The famous opening juxtaposes a peasant girl’s face with a large sunflower. Semion, an aged peasant, is calmly, even cheerfully awaiting his imminent death, lying on a blanket and surrounded by heaps of apples.

A kulak family is soon introduced, angry at the idea that their possessions will be seized. The head of the family declares that he will kill his animals rather than turn them over, and he tries to attack his horse with an axe.

The arrival of the village’s new government-provided tractor marks a shift to an emphasis on the advantages of collective farming. As it approaches, the kulaks stand watching and mocking the idea of a machine taking over. In one shot, an elderly kulak stands framed against the sky, his wealth indicated by the presence of a hefty cow. The tractor temporarily halts, but it turns out that the radiator is dry. The simple solution is for the collective members to urinate into it.

Earth is a visually beautiful film, but like other Soviet classics I have complained about, there is no decent print of it available. The old Kino disc groups it with Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (the cropping of which I mentiooned in the 1927 entry) and Chess Fever. The copy of Earth is too dark and indistinct. To get some frames for illustrations, I watched the visually superior copy on YouTube, but there the images are cropped to a widescreen format. Just as bad, there are ads scattered through it, including one in the middle of Vasyl’s twilight dance in the road just before he is shot!

As before, I must end by pointing out that an archival restoration and a Blu-ray release are in order.

Ozu debuts on the list

Although after 1937 there are years when Ozu did not make a film, he will likely feature on these lists as long as I continue to post them. In 1930 he made six features and a short. Only three survive: Walk Cheerfully, I Flunked, But … , and That Night’s Wife. I’ve chosen the last, though Walk Cheerfully is a viable candidate as well. Sound was adopted slowly in Japan, and Ozu held out until 1936 before releasing his first talkie, The Only Son, which will doubtless feature on my list for that year.

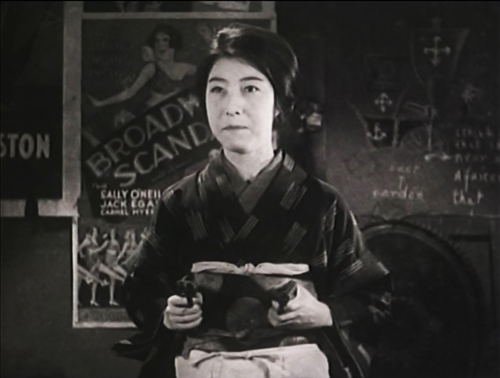

The British Film Institute released That Night’s Wife in a boxed set called “The Gangster Films,” along with Walk Cheerfully and Dragnet Girl. Yes, Ozu made gangster films, including the wonderful Dragnet Girl, the film that might lead me to make my exception in the 1933 entry.

That Night’s Wife, though, is not really a gangster film. Shuji, the father of a daughter with a potentially fatal illness, is not a gang member but a decent working man who stages a hold-up to get money for her medicine. Ozu handles this hoary plot premise with his usual unconventional approach.

The opening, with its shots of dark, empty streets through which the police chase Shuji, is film noir ahead of its time. We soon are introduced to his worried wife, Mayumi, tending the little girl. She’s cute but has a distinctly bratty streak so common to Ozu children. This and fairly frequent moments of subtle humor help Ozu avoid a purely melodramatic presentation of the situation.

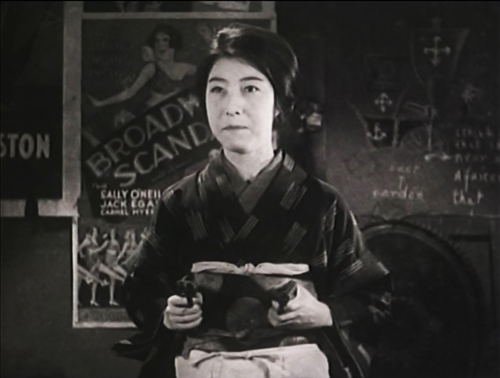

Once Shuji arrives at home, Mayumi gets him to confess what he has done. He intends to turn himself in after the daughter’s crisis passes, but a gruff detective who has posed as a cabby to find out where he lives, appears. Being told that the daughter will only survive if she lasts through the night, the Detective agrees to stay and settles in to guard his prisoner. Mayumi reveals her inner toughness and determination to defend her husband. At one point the Detective dozes off and she steals his gun and points it and her husband’s pistol at him, urging Shuji to escape (above). That shot, by the way, shows a motif typical of early Ozu films: having posters, often for American movies, visible on the walls behind the characters.

That Night’s Wife doesn’t display the fully mature Ozu style, but no one would mistake it for a film by another director. He has already mastered the perfect match on action, and he uses one in the early scene where Mayumi sits down as the doctor tends the daughter. Ozu cuts in with a move across the axis of action that places us 180 degrees on the other side of her.