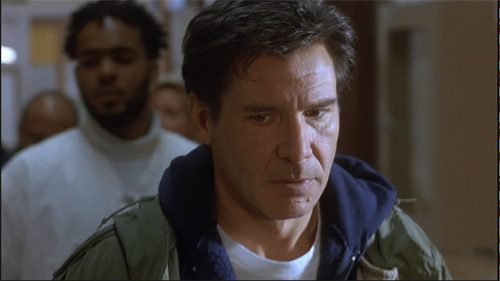

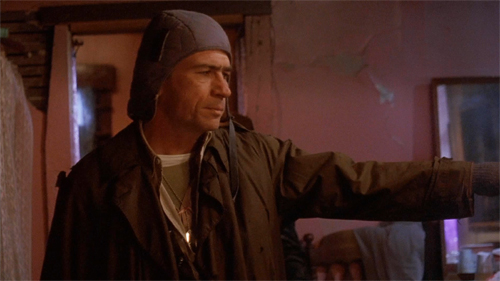

The Fugitive (1993).

DB here:

How do we respond to films? How are they designed to have effects on us? How do our responses outrun the “programmed” effects filmmakers aim to create?

These are perennial questions of film studies. Since the 1990s, neuroscientists have tried mapping our brains’ reactions to moving images, and one school of thought in that tradition has sought answers in the phenomenon of mirror neurons.

In my spring seminar, I tried to introduce students to a bit of this debate. First I laid out what I’ve taken to be the most useful psychological findings for my research–what has been known as “classic cognitivism,” stemming from the New Look psychology of the 1950s and 1960s.

At the same time I wanted the group to consider alternative theories, and the timing of the book The Empathic Screen, by Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra, seemed propitious. In addition, I learned of Malcolm Turvey’s response to their research and brought that essay to the seminar. For some years Malcolm has been advising caution about importing scientific research into humanistic studies generally and film studies in particular.

Because of the coronavirus, our seminar had to meet online, so I prepared an online text version of my planned lecture. One advantage of that was that I could get very long-winded about things. But it also meant I could post a shorter prepublication version of Malcolm’s essay on the subject. And remote access brought him into the seminar to make his case when we met.

I invited a response from Vittorio and Michele, and they duly sent one along. It is published here, followed by comments from Malcolm and me.

If you haven’t read my initial entry or Malcolm’s, I hope you will try before you read what follows. (Just homework; they won’t be on the final.) If you saw them at the time, a quick look back should suffice.

And yes, The Fugitive is involved. Eventually.

The Neuroscience of film: A reply to David Bordwell and Malcolm Turvey, and a contribution to further the debate

Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra

The contribution cognitive neuroscience can offer to film studies and in a broader perspective to the debate within the humanities is at the same time potentially priceless and to be carefully evaluated. Still in its early infancy, the field of “neurohumanities” represents a great challenge to a new way of thinking our relationship with the mediated worlds of the arts. In the last twenty years, more or less, we have been observing a very productive exchange between psychologists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists and scholars from literature, theater, art, music, dance, and cinema, aiming to develop what Shaun Gallagher would call a “critical neuroscience”, suitable to inform a critical theory about the role our brain-body system plays in our aesthetic experiences.

What is at stake here is, on the one hand, the relevance of these experiences in our lives, the nature of our being “storytelling animals” (to borrow Jonathan Gottschall’s definition), both when we produce stories and when we play the role of readers or viewers, and the updating of our embodied relationship with the simulated worlds of the arts and the technologies we live in and through. On the other hand, we are facing a fascinating challenge for theory, in our case film theory, where words like action, interaction, empathy, intersubjectivity, we have been using for years within our fields of study, have to be reconsidered after the neuroscientific discoveries of the last decades.

The idea both of us shared at the beginning of the research that has brought us to perform experiments on cinema, to test the role of motor cognition during film watching and then to the publication of our book The Empathic Screen. Cinema and Neuroscience, was – and still is – that the contribution of cognitive neuroscience is first of all theoretical, as the one of psychology or cognitive science has been within the humanities, and then empirical, trying to shape, step by step, a new proposal to study parts of our film experience, which can confirm, renew, or in some cases overturn our ideas.

We know that the debate is still oscillating between two positions which we could, just to be clear and simple, describe as “neuromaniac” and “neurophobic”, where in the first case the risk is seeing neuroscience as the right place for explaining and clarifying the secret of life, while in the second case the risk is not seeing the productivity of a confrontation with its theories and empirical findings. David Bordwell’s and Malcolm Turvey’s entries on David’s blog about this topic and our book are a relevant sign of the need of debating about neuroscience and film, and we are confident that the next chances for exchange – the film journal Projections is going to schedule an issue to host part of this debate – will widen the discussion, involving scholars with different and enriching positions.

What we would like to do here, as a short reply to some of David’s and Malcolm’s observations, is to put forward three lines for reflection that we consider methodologically important to carry on the debate facing directly the core of the matter, and that guided the writing of The Empathic Screen. First of all, we want to say something about what we mean when we say “neuroscience”, what neurons can do and what they cannot, until where neuroscience can talk, and where it has to stop and leave room to theory and to ideas for new research within this open minded new field. Secondly, we have to ask ourselves which kind of film theory can host such a new debate, how it can converse with the main theories that have been taking the field in the last decades, and how we can think of teams and groups of research able to develop the critical neuroscience we need. Lastly, we would like to say something about why it is important to do experiments, what a serious experiment can give us, and what is its function for the debate (on this point, the abovementioned entries already said something).

1) Critical Neuroscience. It is hardly disputable that there cannot be any mental life without the brain. More controversial is whether the level of description offered by the brain is also sufficient to provide a thorough and biologically plausible account of social cognition – and of aesthetic experience. We think it isn’t. Such assertion is based on two arguments: the first one deals with the often overlooked intrinsic limitations of the approach adopting the brain level of description, particularly when the brain is considered detached from the body, or when its intimate relation with the body and the contextualized relation the body entertains with the world are neglected. The second argument deals with social cognitive neuroscience’s current prevalent explanatory objectives and contents, in many quarters still dominated by the logocentric solipsism heralded by classic cognitivism. As we wrote in the book, we think that “neuroscience can offer a genuine contribution to the re-definition and comprehension on new empirical grounds of fundamental and paradigmatic themes of the human condition, such as the perception of images and the construction of our network of relations with objects and other human beings.

Action, perception and cognition are terms and concepts describing different modalities which are permanently bound by the embodied and relational essence of all living beings, including humans.” In that respect, some theoretical premises David Bordwell cites, like the modular mind as proposed by the analytic philosopher Jerry Fodor, are patently contradicted by neuroscientific research. At the same time, to quote our book again, “If the neuroscientific approach to cinema [proposed in this book] is to be applied successfully, it must be critical, its potential and its heuristic limitations must be clear, it must be open to dialogue and constructive collaboration with other disciplines such as the history of cinema and the theory of film, philosophy and other fields of studies.” Neurosciences are aptly declined in the plural, because in spite of the same basic methodological approaches and methodologies, the questions neuroscientists ask and the answers they are seeking by applying those approaches and methodologies can be incredibly different.

In the last thirty years or so, when investigating human social cognition cognitive neuroscience has mainly tried to locate the abovementioned cognitive modules in the human brain. Such an approach suffers from ontological reductionism, because it reifies human subjectivity and intersubjectivity within a mass of neurons variously distributed in the brain. This ontological reductionism chooses as level of description the activation of segregated cerebral areas or, at best, the activation of circuits that connect different areas and regions of the brain. However, if brain imaging is not backed up by a detailed phenomenological analysis of the perceptual, motor and cognitive processes that it aims to study and – even more importantly – if the results are not interpreted on the basis of the comparative study of the activity of single neurons in animal models, and the study of clinical patients, cognitive neuroscience, when exclusively consisting in brain imaging loses much of its heuristic power and reduces to a 2.0 version of phrenology.

It should be added that the competence of understanding others -real people as well as fictional character- is uniquely describable at the personal level, and therefore is not entirely reducible to the sub-personal activation of neural networks in the brain, hypothetically specialized in mind-reading, as too many neuroscientists nowadays think. Indeed, neurons are not epistemic agents. The only things neurons “know” about the world are the ions constantly flowing through their membranes. Thus, we think that the final goal of cognitive neuroscience should be to profitably and personally conjugate the experiential dimension through a study of the underlying sub-personal processes and mechanisms expressed by the brain, by its neurons, and by the body. A cognitive archeology that can successfully integrate our knowledge of the personal level of our experiences.

2) Film theory. For what concerns its theoretical contribution to film studies, our position in The Empathic Screen is that cognitive neuroscience can play a role in the study of spectatorship, film style, and the analysis of new devices and the ways we interact with them. Obviously these aspects are strongly intertwined, as when we study the effects of camera movements on motor cortex activation (in one out of the six chapters of the book) we are, for instance, already studying the viewer’s basic response and his or her motor involvement during film watching, the impact of some stylistic elements on film composition, and the evolution of these movements in new aesthetic forms like those implied by an action camera, or a drone (this is also the reason why we decided to dedicate the last chapter of the book to the matter of new mediations provided by the screens of our laptops, smartphones, and the like).

Though David wrote that our book is “the fullest account” of mirror neurons application to cinema, we think that it would be more correct to say that The Empathic Screen is perhaps the fullest account of the application of embodied simulation (ES) theory to film studies. Basically, this is what we have been working on since 2012, when a first theoretical article (“Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies”) appeared in Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image, and then when we presented and discussed the outcomes of our three film experiments in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Cognitive Science, and PloS One. Of course, ES relies on the discovery of mirror neurons, but as it has been demonstrated in an articulated debate which has gone through philosophy, aesthetics, psychology, psychoanalysis, linguistics, and the arts, ES theory goes beyond the (scientifically proved) action and functioning of mirror neurons to enter the discussion on the role our brain-body system plays when it is engaged in real life and virtual environments.

We found that the questions raised by ES theory had been to some extent anticipated by the first physiological studies on film between the 1910s and 1920s (with relevant examples in Italy and France), and the almost coeval American literature on the didactics of cinema, where people like Epes Winthrop Sargent, Henry Albert Phillips, or Victor Oscar Freeburg focused both on “action” as the basis for film style and cinematic intersubjectivity, and the idea that the response of our senses to film movement, like to any physical movement, takes place before we have time to interpret the dramatic significance of the visible stimulus. Of course, as argued in our book, we do not think that film experience could be explained just focusing on action and the viewer’s responses to motor stimuli, but we think that film cognition should not ignore the role of motor cognition, and unfortunately this is what happened till now with few exceptions (the more noticeable back in the 1920s, then in the ambitious season of French filmology, and in some notes by Maurice Merleau-Ponty for a 1953 course at the Collège de France). Neuroscience can provide inspiration to explore this field, and it can also provide new methodologies to support theories and to update and problematize some of them.

Sometimes the most skeptical scholars say that neuroscience when applied to arts, tells us nothing new, or just already expected things. Obviously, we could say the same of semiotics, phenomenology, or cognitive science, but this is not the point. We do not need just “new things”, or new data, we need theories capable of raising more questions, of articulating and inspiring new lines of research, of shedding light again on neglected topics. Otherwise we would fall in the trap of expecting the definitive answers from the study of the brain. As we wrote in the Introduction to the book, our goal was “to present a study of film starting from the sensorimotor and affective implications, identifying a series of neurophysiological mechanisms as a tool for the deconstruction and comprehension of the conceptual instruments usually adopted in debates on the various aspects of cinema.” From this perspective Murray Smith, in his Foreword, emphasizes very well our pluralist approach across the history of film theory, putting forward the strong proposal of a new conjugation of the experiential dimension of cinema with the study of the underlying sub-personal processes and mechanisms expressed by the brain-body. It is from here that a discussion has to start. To us, it is not useful to give up such a complex and enriching debate taking a pessimistic position that does not consider the complete scientific debate behind ES theory. The history of film theory, from the classical period to the present, has greatly profited of the confrontation with science, even when some insightful observations came from very debated arguments (sometimes not confirmed arguments, unlike the case of mirror neurons). This doesn’t mean that we have to ignore the debate around scientific matters, but that we have to cope differently and more profoundly with the science on the theories we propose and discuss, not being “optimistic” or “pessimistic” (read, in this case, neuromaniac or neurophobic), but just informed and critical.

3) Experiments. In his essay David Bordwell wrote “my model of the spectator is agnostic about how the processes are instantiated in physical stuff. Doubtless retinas and neurons and inner ears and the nervous system are involved, but I’m not providing the details. I have no idea how to do so.” Neuroscientific experiments, as those described in The Empathic Screen, aim to shed light upon the contribution of the brain-body to our relationship with films. As we wrote in the book, “What appears on the screen, the ways and means, the strategies of appearance in cinema are the result of the direct relationship our perceptual system has with technology and are influenced by production processes and needs that consolidate the social aspects.” The naturalization of mediated forms of intersubjectivity, such as the experience of film, should start from the deconstruction and reconfiguration of the concepts that we normally use to describe it, by literally studying their component parts and where they come from through the experimental approach of investigation and the level of description of the brain-body system allowed by neuroscience.

To that purpose, we decided to start investigating some important elements of film style, whose intrinsic performative character is betrayed by its etymology from the Latin stilus, the ancient writing tool. We did so by focusing on some constitutive elements of what does it mean to perceive a film: camera movements and montage, which filmmakers employ to modulate spectators’ engagement and possibly intensify it. We decided to side with what many filmmakers do, that is, conceiving of style from a bottom-up perspective, concerned with the perception of film and the ways to calibrate what the spectators see. We should add that our take on visual perception, hence on film perception, parts from the standard account of vision as the mere expression of the visual part of the brain. To the contrary, evidence shows that vision is multimodal, as it encompasses the activation of motor-, tactile- and emotion-related brain circuits.

The experiments on camera movements described in The Empathic Screen, kindly discussed by David Bordwell and Malcolm Turvey, were originated by the idea that it is possible to test whether and to which extent spectators’ bodily perception of the film can be partly determined by their simulation of camera movements. The rationale being that the more these movements mimic human bodily movements –as with the Steadicam– the more they activate motor simulation in spectators’ brains, hence intensifying their reactions to them.

Thus, in the first experiment we correlated the electroencephalographic activation of spectators’ brains during the observation of clips showing an actor performing hand actions shot with a still camera, zoom lens, dolly and Steadicam with their explicit rating of engagement with the same clips. The results showed that clips shot with the Steadicam evoked the strongest motor simulation and correlated with the most intense perception of camera movements’ resemblance of realistic bodily movements and identification with the filmed actor (see Heimann et al., 2014).

In the second experiment the same rationale was used to test what happens when the different camera movements film an empty room. Once more, and in spite of the total lack of filmed bodily actions, the spectators’ brains showed the strongest motor simulation when perceiving clips shot with the Steadicam. In this experiment, we added some open questions to further explore the spectators’ phenomenal experience of the observed film clips: the results showed that the Steadicam induced the strongest motor simulation and led the participants to feel like walking together with the camera’s eye (see Heimann et al., 2019).

Taken together, these two pioneering experiment show for the first time that the Steadicam’s power of bringing the audience literally into the scene is related to its capacity to trigger stronger motor simulation and stronger feelings of engagement than all the other tested camera movements. We never claimed that spectators’ whole film engagement amounts to simulating camera movements. We argued that, “If film has something to do with subjectivity, it is to the extent that its moving form bears the imprint of a subjectivity”, as posited by Dominique Chateau, our two experiments provide empirical support to the idea that the intersubjectivity instantiated by film can be profitably studied by focusing on the ‘motor cognition’ stimulated in spectators by the film techniques employed. Furthermore, we think that our results can also offer a valid contribution to the debate within film studies on the supposed lack of subjectivity of the Steadicam, as argued by Jean-Pierre Geuens (1993-94) who held that the Steadicam produces a totally disembodied type of viewing.

Even when delimiting in such a way the field of empirical investigation, as we did with our experiments, a caveat is in order: one should bear in mind that a lab is not a movie theatre and participants in the experiment are not members of a film audience (film scholars are obviously perfectly aware of this aspect, as it is at the basis of several experiments in the field of the neuroscience of film). The whole experimental context aims at mimicking those conditions in the best possible way, but it remains true that experimental conditions are nothing but an oversimplified and coarse replica of real life situations. Of course, this does not apply just to our experimental approach to cinema, but to cognitive neuroscience at large.

Any empirical approach uses experiments to verify hypotheses that generate predictions. Obviously, both hypotheses and predictions do not grow out from the void, but are consonant to and inspired by the presupposed theoretical background, hopefully based on previous empirical evidence.

We think that our hypotheses are based on rock-solid ground, as they capitalize upon almost three decades of neuroscientific research on the perceptual and cognitive role of the motor system, with results that go from single neurons’ recordings in macaques, birds, rodents and humans to non-invasive behavioral, EEG, and fMRI studies carried out on the human brain in hundreds of labs around the world. We believe that the adoption of a comparative perspective, framing the cognitive functions and aesthetic proclivities of humans within a broader evolutionary scenario may secure a deeper understanding of human cognition – hence also of film perception – than the experimental approach still endorsed by many cognitive neuroscientists, whose study of the brain translates in the neo-phrenologic reification of the ‘boxology’ of classic cognitive science into brain areas, supposedly housing the very same boxes. A telling example comes from the endless brain imaging experiments realized to support the hypothesis that propositional attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires and intentions) ‘reside’ in distinct brain areas. Unfortunately, empirical evidence showed that the activation of those brain areas is neither causally relevant nor specific to engage in mindreading activity, whatever that means.

We think that these experiments that still receive the acritical acceptance by many quarters of cognitive science, are less illuminating on the relationship between brain and cognition than the perspective offered by the embodied cognition approach. With our book, we aimed to show the heuristic potentialities of this approach when applied to film theory.

When the debate starts, it means that it is time to make a new and updated point on the forms of confrontation between science and the arts, what we try to do, coming from a different training, working around the multiannual project of The Empathic Screen, and keeping open the discussion with colleagues, friends, and scholars from several fields of research. Are we exerting an optimism both of intellect and will? We don’t know, we are just doing research in a very challenging and promising field.

Response from Malcolm Turvey

I thank Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra for their reply to my blog entry about their book, The Empathic Screen, and its arguments about camera movement. Although they do not respond to my criticisms of their work, in their reply they reiterate some of the principles informing their neuroscientific research on cinema as well as the results of their experiments. Here, I will comment on some of these, pointing to areas of both agreement and disagreement.

Gallese and Guerra contrast what they call the “neuromaniac” and “neurophobic” positions about the role of neuroscience in film studies. Personally, I don’t subscribe to either. My position (which I develop in a forthcoming paper in Projections from which my blog entry is extracted) is what I call serious pessimism about the possible contribution of neuroscience to the study of film and art. Serious pessimism is not neurophobia, as there is nothing to fear about neuroscience (except perhaps overconfidence in its explanatory possibilities). Rather, I doubt that neuroscience can answer certain kinds of questions we standardly ask about film and the other arts, and I’ll provide an example in a moment. But even if I am wrong about this, the neuroscience of film is still in its infancy, and we must wait and see whether its discoveries have a significant impact on our discipline or not. New scientific paradigms often generate an “irrational exuberance” about their explanatory possibilities until researchers less invested in their success expose their flaws and limitations. I think we should suspend judgment about the contribution of neuroscience to film studies until more results are in. Call me “neuro-cautious.”

This is not Gallese and Guerra’s position. Although they claim not to be “neuromaniacs,” they seem to assume that neuroscience, or at least their version of it, will have a major impact on the study of film and the arts if it hasn’t already. They write in their reply that it “represents a great challenge,” that “words like action, interaction, empathy, intersubjectivity [that] we have been using for years within our fields of study, have to be reconsidered after the neuroscientific discoveries of the last decades,” and that their work is “a tool for the deconstruction and comprehension of the conceptual instruments usually adopted in debates on the various aspects of cinema.”

Notice, however, that they do not provide a single example of how the neuroscience of film has required us to revise our concepts of cinema, and I find it hard pressed to think of any. To be sure, neuroscience can and has revealed the neural underpinnings of our perceptual, cognitive, affective, and bodily capacities, including those engaged by film and other forms of the moving image. Perhaps it will also lead to a conceptual revision at some point, at least in our theories of cinema. But it hasn’t, to my knowledge, done so yet.

For example, the two experiments that Gallese and Guerra have undertaken on camera movement seem to show, as they report, that “the Steadicam’s power of bringing the audience literally into the scene is related to its capacity to trigger stronger motor simulation and stronger feelings of engagement than all the other tested camera movements” (my emphasis). I write “seem” to show because in my blog entry and the longer article from which it is extracted, I provide a number of reasons why Gallese and Guerra’s two experiments don’t in fact support their thesis about the Steadicam and camera movement. Most obviously, it cannot “literally” be the case that we are brought “into the scene” when simulating a Steadicam’s movements because, literally speaking, we are typically sitting in a seat while watching a film. But even if a deflationary version of this thesis is defensible, in what respect does it necessitate conceptual revision or represent “a great challenge”? They do not say.

Gallese and Guerra’s more modest assertion that “cognitive neuroscience can play a role in the study of spectatorship, film style, and the analysis of new devices and the ways we interact with them,” is, I think, incontestable, although, to repeat, it is an open question how big a role. This does not mean, however, that we should accept every neuroscientific theory of film unconditionally. As with any theory, a neuroscientific theory must be tested. Is it conceptually precise and logically coherent? Are its conclusions licensed by the evidence? Are there better theories? Just because one contests a specific neuroscientific theory, as I do in the case of Gallese and Guerra’s theory, does not mean one rejects neuroscience or is a neurophobe. Indeed, the testing of theories is one reason why (neuro-)science, and other forms of rational inquiry, make progress. Unfortunately, perhaps due to the authority of science, film scholars who draw on scientific paradigms such as mirror neuron research and Embodied Simulation sometimes neglect to do this, including Gallese and Guerra in their book.

Gallese and Guerra are also right, I think, to warn against “ontological reductionism” in neuroscientific film studies. For there is much we can discover about camera movement and other aspects of film without knowledge of the “sub-personal” level of the brain. For instance, in his book the The Dynamic Frame, Patrick Keating explores the rich history of camera movement in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood, showing how available technologies along with industrial organization shaped the use of various types of camera movement by filmmakers for specific purposes, such as revealing characters’ mental states. He does all of this without appealing to neuroscience, and in general much of film studies, like the humanities more broadly, is aimed at understanding the “personal” level of intentional, broadly rational actions (“the space of reasons”) of human beings in particular historical circumstances.

Neuroscientific descriptions of brain activity won’t tell us the reason(s) Hitchcock used the short dolly or tracking shot toward Sebastian’s keys in the scene from Notorious that Gallese and Guerra discuss in their book and I in my blog entry, or the function Hitchcock intended it to perform in the film. Nor will they tell us anything about the historical conditions–the available technologies, the craft practices operative in Hollywood at the time, the financial and other industrial conditions of the moment, the period norms governing camera movement–that constrained and shaped Hitchcock’s decision to use that particular camera movement where and when he did. To be sure, neuroscientific explanations may be able to supplement, enrich and perhaps even modify humanistic ones such as Keating’s. But this does not mean they replace them. This is one reason I am pessimistic about the contribution of neuroscience to film studies.

Gallese and Guerra would presumably agree with at least some of this, as they rightly decry the “endless brain imaging experiments realized to support the hypothesis that propositional attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires and intentions) ‘reside’ in distinct brain areas.” They also warn that “neurons are not epistemic agents. The only things neurons ‘know’ about the world are the ions constantly flowing through their membranes.” However, it is not clear to me that their theory avoids either reductionism or the homunculus fallacy. For all of their talk of “embodied” cognition and simulation, and their professed hostility to “classical cognitivism,” they seem to locate the viewer’s purported feeling of being brought “into the scene” in a brain area too, namely, the activation of the motor cortex by camera movement. Identifying an area of the brain (the motor cortex) and correlating its activation with an observable form of human behavior (feeling that one is brought “into the scene”) seems like pretty standard brain science to me. And there could be many reasons a viewer feels that they are brought “into a scene” in addition to the degree of motor cortex activation in their brains. Meanwhile, in claiming that our neurons “simulate” the actions of others (including Steadicams), Gallese and Guerra appear to be guilty of ascribing “knowledge” to neurons. For how do our neurons “know” the meaning or purpose of the action they are supposed to simulate? And to who or what do they simulate it? I point to these and many other problems with their account in my forthcoming paper in Projections.

Science, and rational inquiry more broadly make progress in part through rigorous criticism of theories. Theories are either discarded in light of criticisms, or they prosper through successful efforts to show that criticisms of them can rebutted or that they can be improved in light of said criticisms. It is notable that Gallese and Guerra don’t engage with any of my (or David’s) criticisms of their theory in their reply. I would love to learn from them why I am wrong: why, in other words, there is after all enough empirical data to support their bold claim about camera movement, why the counter-examples I cite don’t in fact disprove their theory but can be accommodated by it, why they are not guilty of the homunculus fallacy among other philosophical errors, and so on. I would love, in other words, to learn why I shouldn’t be so skeptical of their theory of camera movement and the mirror neuron research informing it. But this can only happen if they respond to criticisms of their theory and show why they are mistaken.

There is no doubt that neuroscience has a role to play in film studies. The doubt, on my part at least, is about Gallese and Guerra’s specific neuroscientific theory of cinema.

Some final remarks from DB

I see Vittorio and Michele’s reply as a promissory note. It’s a delineation of their difference from other neuroscientific researchers and an aspirational account of their future contributions. It doesn’t, as far as I can tell, offer any replies to Malcolm’s or my criticisms of the arguments laid out in their book.

For example, they claim that in Notorious, any suspense we feel “has nothing whatsoever to do with the story” (p. 54). Malcolm’s essay suggests that what they call a “precise schema of camera movements and editing that keeps us on the edge of our seats” works largely because of higher-level knowledge we have of the plot, the situation that the heroine is in, and what’s at stake in her duplicity. Vittorio and Michele do not here clarify or qualify their argument.

Likewise, reading that La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc is an example of the “oppressiveness” of the fixed camera, compelled me to mention that the film is filled with camera movements; in fact, it starts with one. More generally, their claim that “the involvement of the average spectator is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements” (p. 91) would make most of the first thirty years of cinema pretty uninvolving. But then, what does “involving” mean here?

Most generally, I would be interested in Vittorio and Michele’s response, however brief, to the critique of mirror-neuron theory advanced by Gregory Hickok in The Myth of Mirror Neurons and other writings. They mention above “the (scientifically proved) action and functioning of mirror neurons” without further explanation, but as an outsider browsing the literature, I’m struck by a good deal of debate about these neurons’ status and functions. Here, for example, is an interesting exchange between Vittorio and Hickok from 2015. There’s a good, nontechnical talk by Hickok from three years later.

My amateur sense is that Vittorio and Michele have relaxed a strict adherence to mirror-neuron accounts in favor of what they call Embodied Simulation, a broader view close to phenomenology. I am not sure that this is necessarily a step forward. Phenomenology all too often proffers lyrical description rather than concrete explanation. In any case, I take it that their position relies upon the Simulation Theory of Mind, an alternative to the “Theory of Mind” Theory. It would be good if they would spell out how ES is preferable to its philosophical rival.

There is much more in The Empathic Screen that should be discussed. The chapter on multimodality offers a lot of evidence on how visual stimuli can activate the sense of touch. There’s also a great deal of broad critical commentary on particular films, and frequent invocations of earlier film theorists. This last point is raised in their reply. I have to say that claiming one’s theory harmonizes with an earlier theory isn’t itself terribly convincing, for the reason that the early theory might be faulty. As for the critical interpretations offered in the book, many of those seem detachable from the theories being proposed. Several I find hard to follow. (“While in the zoom-out the iconic annuls the diegetic, in the zoom-in the reasoning of the diegetic limits that of the iconic,” 99).

On one new point Vittorio and Michele make in their reply, I want to register a specific disagreement. They write:

Sometimes the most skeptical scholars say that neuroscience when applied to arts, tells us nothing new, or just already expected things. Obviously, we could say the same of semiotics, phenomenology, or cognitive science, but this is not the point.

Actually, I think that semiotics and cognitive science have produced fresh knowledge about film. (Phenomenology is another story.) Often these lines of inquiry show that apparently unconnected phenomena have fairly coherent underlying principles. Exposing their “logic” allows us to understand creative options. For instance, Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film, probably the most famous, or notorious, semiological enterprise, showed that there might be a coherent set of expressive alternatives in constructing scenes and sequences. The concepts of paradigm and syntagm did useful work in organizing craft practices and audience skills.

Similarly, I’d argue that robust cognitive findings like the primacy effect, anchoring, belief fixation, “folk psychology,” hindsight bias, and “the curse of knowledge” help us understand something important about how stories are constructed. They suggest that principles of narrative construction and uptake depend on both folk causality and informal reasoning routines, the heuristics and biases and shortcuts we use in everyday life. Again, ideas from another discipline can reveal patterns we might not otherwise detect. We want to make new discoveries, not re-label things we already know!

For now, I’ll finish with a couple of broad points about the book’s research strategies. This is an effort to specify further the outlines Vittorio and Michele offer above.

I consider film studies largely an empirical enterprise. Not an empiricist one: We need concepts, hypotheses, rival explanations, interrogation of our presuppositions, and the like. Central to the enterprise, I think are precise research questions that we can recast as analyzable problems. Even though Vittorio and Michele claim that their perspective will generate new questions, I am left wondering exactly what those are.

I infer that they are searching for causal accounts of film style. I’m hospitable to this impulse. I once hoped that mirror neurons could be part of a causal explanation of certain responses we have to film. But I think the results so far are scanty and vague, for reasons rehearsed in my entry.

So if I had to imagine a research program along this line, I think I’d try to start by defining what is meant by “immersion,” “empathy,” and other conceptions of response. Like Malcolm, I’m puzzled by the claim above that the Steadicam is “bringing the audience literally into the scene.” (I’d say it’s bringing us imaginatively into the scene, as do other film techniques.) Operational definitions of these responses would seem to be a first step in a research program.

Then a research program could systematically sort stylistic parameters without weighting any one, considering staging, sound, lighting, editing, and camerawork. Each of those expressive resources of the medium presumably shape the way spectators respond. (I think narrative does too, but that seems to operate as a taken-for-granted background for Vittorio and Michele, when they don’t dismiss it as inconsequential.) As a general principle, it might be good to assume that all of these families of techniques can contribute to audience effect (and thus brain activity).

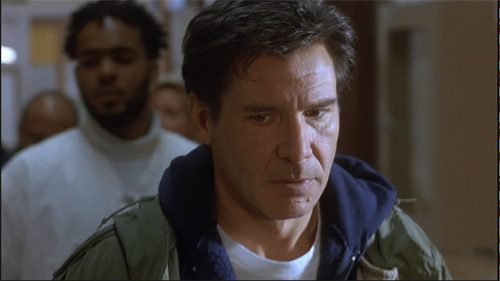

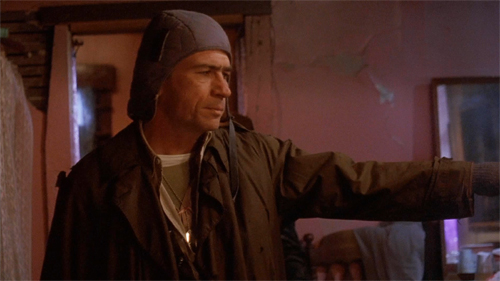

Then one might pose some middle-level questions about, say, camera movement. That process might start by recognizing that there are many trajectories of movement. The forward-moving shot–the kind that the two experiments in question measure–is only one creative option. In The Fugitive, and probably in many other films, bare-bones forward Steadicam shots are less common than ones motivated as advancing point-of-view shots.

And especially in the era of the Steadicam, there are plenty of track-back following shots.

Embodiment theorists tend to hold that advancing camera movements are involving because they mimic our thrusting into the world, but shots like this don’t display that likeness to ordinary bodily movement. (Try walking backward for any sustained period.) I’d hazard a guess that reverse tracking shots are at least as common as forward-moving ones. And there are of course sidelong and lateral Steadicam shots as well. All deserve comparative neurological investigation, it would seem.

A lot of theorizing depends on picking prototypes of a phenomenon. For decades, historians took Griffith-style crosscutting as their prototype of editing, thereby paying less attention to the more common analytical continuity that rules most scenes. New Look psychology took visual illusions as prototypes of perceptual problem-solving. The forward tracking shot, I think, is Vittorio and Michele’s prototypical example of embodied film experience. Accordingly, their discussion of The Shining tends to downplay the reverse-tracking shots in that film, instead suggesting that the camera is stalking the characters like a ghost, “walking or running behind Danny or Jack Torrance. . . a POV shot by an unknown entity” (p. 100). I think they could fruitfully broaden their view to consider the rich menu of camera-movement options. Perhaps they would say that a backward tracking movement is less intensely involving than a forward-moving one, like the one I’ve excerpted above.

Sometimes causal factors and functional ones mesh. Why do so many filmmakers employ the retreating movement, on tracks or with Steadicam, for those already normative “walk-and-talk” long takes? Well, such shots are more informative for narrative purposes: on the move, we can see faces, gestures, lip movements, and the like.

By contrast, a forward-moving shot trailing a character, captured in Steadicam or not, isn’t providing that sort of information. The framing throws our attention not on the figure but on what’s coming up in the distance, or in rarer cases what’s going on behind a character’s back.

This isn’t to downplay causal explanations; it’s just a matter of recognizing that they need to be framed as part of a broader range of possibilities. Saying that (forward) camera movement yields more “involvement” than other techniques looks like balancing a pyramid on its point.

I concur with Malcolm that much of what we want to explain about cinema requires causal explanations of a different sort. We will, for instance, impute intentions to filmmakers (as Vittorio and Michele do with Hitchcock, Kubrick, and others). When we assume that Hitchcock is aiming to amp up suspense, we aren’t requesting information about his subpersonal brain activity. We want to invoke plausible personal causes (e.g., his beliefs, desires, plans) and suprapersonal causes, such as the rules and roles assigned to filmmakers by the institutions they work within.

We’ll also, I think, want to mount functional as well as causal explanations. That effort entails commitments to ideas about form, style, theme, subject matter, and other matters that, at least at present, don’t reduce to neurons firing.

My blog entry tried to make the case for an “agnostic functionalism” that leaves open many explanations at the brain/body level but still aims for cogent explanations–both causal and functional–of artistic qualities we detect in films. Without benefit of electrode caps we can detect cues and patterns that are designed to shape our uptake. It’s a matter of paying attention to what we see and hear, of being alert to patterns and purposes, and of knowing relevant filmmaking conventions and traditions.

That analytical perspective informed my examples from Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Summer at Grandpa’s and Preminger’s River of No Return, where I argue we can study a director’s strategies of blocking information or guiding our attention. These strategies shape the purpose and effect of particular scenes. And these examples do it by refraining from camera movement. Even when camera movement is present, as in the train crash in The Fugitive, it’s “Bouncycam,” not the type Vittorio and Michele’s experiment found optimally “involving.” Yet I think most viewers wouldn’t ask for more camera movements in this sequence.

This sequence’s gestures of clutching, stretching, fumbling, twisting, leaping, and the like might well trigger some “mirroring” brain activity in spectators. But surely the force of this sequence comes from the detailed sculpting of these appeals. Staging, cutting, sound (music included), performance, lighting, and other factors are all sharpened for maximum comprehension and “action physics” (looming, fast approach to camera). And of course there’s the ongoing plot incidents, the fluctuations in Kimble’s situation from moment to moment, the twists in the situation cascading past us with just enough time for us to grasp each one. However important The Body is, we should remember that properly paced intelligibility is engrossing. Just filming all those hand gestures willy-nilly wouldn’t yield the same impact.

Are brains involved? Certainly. Maybe we should invoke the distinction between necessary and sufficient conditions, or distal and proximate explanations. In any case, it’s not yet evident to me that brain science will answer questions about form and style that can be considered with more nuance by research traditions inquiring into film craft and artistry.

Thanks to Vittorio, Michele, and Malcolm for their participation in this entry. A longer version of Malcolm’s piece is forthcoming in Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind, with further responses from Vittorio and Michele. Further discussion of Malcolm’s paper, with Vittorio and others participating, took place at the virtual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image in June. You can watch the result here.

Many members of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image have studied how cognitive psychology can illuminate aspects of film. I try to tackle some of these ideas in Narration in the Fiction Film and essays in Poetics of Cinema. See also the Film theory: Cognitivism tag on this site.

See also Vera Tobin’s Elements of Surprise: Our Mental Limits and the Satisfactions of Plot. Vera was a keynote speaker for our June conference: her presentation and discussion are here. Speaking of that conference, we all owe Carl Plantinga and Dirk Eitzen a great deal for pushing forward on it during the health crisis.

The Fugitive.