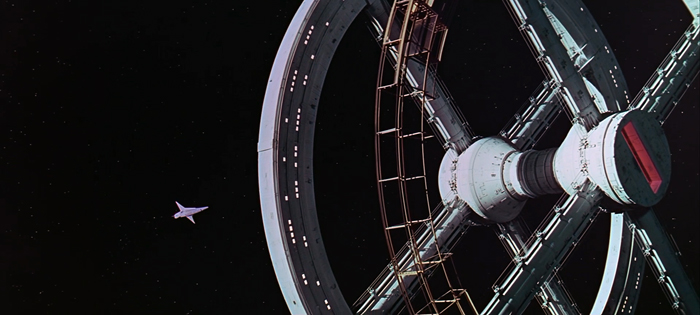

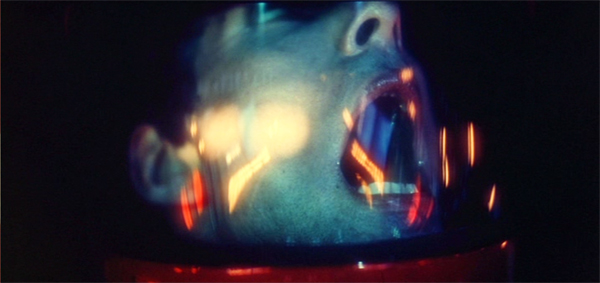

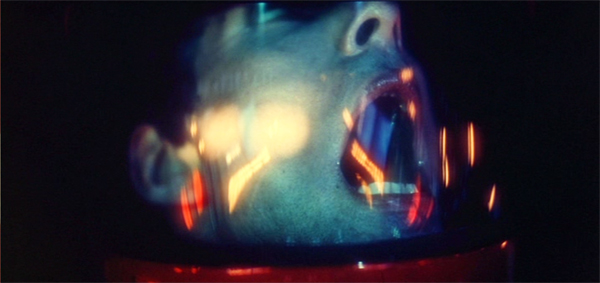

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

DB here:

Over the years we’ve brought you several guest posts from friends whose research we admire. The list includes Matthew Bernstein, Kelley Conway, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, Eric Dienstfrey, Rory Kelly, Tim Smith, Amanda McQueen, Jim Udden, David Vanden Bossche, and our regular collaborator Jeff Smith (most recently, on Once Upon a Time in Hollywood…).

Today our guest is Malcolm Turvey, Sol Gittleman Professor in Film and Media Studies at Tufts University. Malcolm has long been a voice calling for rigorous humanistic study of film. His books include Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition (2008) and The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s (2011). Just this year he published Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism. (More on this in a future blog entry.) Among his many specialties, Malcolm applies the philosophical tools of conceptual analysis to problems of film criticism and theory.

My previous entry discussed some ways psychological research has helped me understand how films work, and I touched on the recent efforts to invoke mirror neurons to explain some effects that movies have on us. Today Malcolm takes a deeper plunge into this line of thinking, and the result is an exciting instance of how careful intellectual debate can be carried out in film studies. It’s also a cautionary tale about relying on scientific research to explain the appeal of artworks. A more extensive version of this piece is slated for publication in Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains) is one of a group of Nazis who have relocated to Brazil after WWII. He has unwittingly married Alicia Hubermann (Ingrid Bergman), an undercover American agent seeking his circle. When Alicia learns that their scheme somehow involves the wine bottles locked in her husband’s cellar, she decides to procure the key so that she and her handler (and lover), Devlin (Cary Grant), can investigate.

Her opportunity comes in a characteristically suspenseful scene. Alicia nervously contemplates her husband’s keychain lying on a bureau as he finishes taking a shower nearby. She bravely steals the key and barely escapes discovery as Alex emerges from the bathroom. But what is the source of the scene’s suspense?

In a provocative new book titled The Empathic Screen, Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra claim the suspense should be attributed primarily to a brief, “human-like” camera movement toward the keys that occurs as Alicia looks at them. Moreover, they draw on neuroscience, specifically the science of mirror neurons, to make their case.

Here is the scene.

Are Gallese and Guerra right about the role played by the camera movement? For reasons I’ll give shortly, I doubt they are. More importantly, I question whether the neuroscientific evidence they lean on supports their case. This may seem like nit-picking, but I think their appeal to neuroscience contains valuable lessons about how students of film should–and shouldn’t–engage with scientific research.

Science and film studies

Readers of this blog are likely familiar with the idea that science has an important role to play in film studies. Since 1985, David Bordwell has drawn on contemporary cognitive psychology to answer questions about perceiving and understanding narrative films, thereby launching a new paradigm in film theory that has come to be known as cognitivism. In his previous entry, David offers an overview of his current thinking about cognition and movies.

Cognitivism has generated much heat in academic film studies. But at its heart is what should be an uncontroversial principle: that those who wish to understand the perceptual, cognitive, and affective capacities with which we engage with art should turn to the work of those who know something about these capacities, namely, the psychologists and other scientists who study them empirically and propose theories about them in light of their findings.

This is because our pre-scientific, “folk” understanding of our psychological capacities is usually non-existent or flawed. It is, for instance, hard to explain why we see still frames as moving images when they are projected above a certain speed merely by reflecting on our “phenomenological” experience of watching movies.

Perceptual psychologists, however, have studied this phenomenon empirically and have proposed explanations for it, such as critical flicker fusion frequency and the phi phenomenon (although like all scientific explanations, these are open to revision and even falsification in the light of new evidence and theorizing). The same is true of other features of our experience of films, and cognitive film scholars have built on David’s work by drawing on contemporary scientific knowledge of emotion, music, moral psychology and much else.

This does not mean that film studies is or should be a science. As David and Kristin’s blog entries repeatedly demonstrate, many of the things we want to know about cinema and the other arts can be discovered through non-scientific, humanistic methods such as analyzing films and researching the context in which they were made. In other words, our methods should be tailored to the questions we ask. Cognitivism argues that some important questions about the cinema can be answered by science, not that all or even most can.

The deceptive authority of Science

That said, I worry that engaging with science in a responsible manner is much more difficult than some of my cognitivist colleagues acknowledge. That difficulty is due, in part, to the “authority” of science.

Because of this authority, many non-scientists might assume that science is more settled than it often is, especially in a human science such as psychology. Those of us who aren’t scientists could be tempted to think that a scientific argument must be true because, well, there are scientific data to support it.

But as the recent “repligate” controversy in psychology and elsewhere shows, just because a scientist can present evidence for their views does not make them true. Data can be unreliable and the conclusions drawn from themunwarranted, as we are witnessing on a daily basis during the coronavirus pandemic.

Although there are occasional scientific revolutions, if science makes progress, something that some ph0ilosophers have questioned, it usually does so incrementally through trial and error, and there is much more failure than success. Those of us who don’t participate in this dialectical process might be apt to forget the provisional, tenuous status of much scientific research and accord it more certainty than it warrants.

Mirror neurons: The controversy

This has happened, I believe, with mirror neurons, a new scientific paradigm that has emerged over the past few decades and that some film scholars have started to draw on to explain some of our responses to films, such as empathizing with characters.

Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when a subject executes a movement and when the subject sees the same movement executed by another. They were first discovered in the early 1990s in the motor cortex of pigtail macaque monkeys by a group of neuroscientists in Parma, Italy, and they have been invoked to explain a wide array of human behaviors such as language, imitation, empathy, art appreciation, and autism.

This is because mirror neurons appear to provide an explanation for how macaques and human beings understand the actions of their conspecifics. Researchers speculate that, if the same neurons fire when a subject reaches for an object, say food, and when the subject observes another agent reaching for food, the subject must be simulating the observed reaching-for-food action in its brain without actually executing it.

By simulating the observed reaching-for-food movement in its neurons, the subject knows the meaning of the movement–reaching for food–because it has performed the movement itself in the past, and attributes that meaning to the action being executed by the agent it observes, thereby comprehending it. As Marco Iacoboni puts it in a popular treatment of the subject:

To see . . . athletes perform is to perform ourselves. Some of the same neurons that fire when we watch a player catch a ball also fire when we catch a ball ourselves. It is as if by watching, we are also playing the game. We understand the players’ actions because we have a template in our brains for that action, a template based on our own movements.

Yet within neuroscience, mirror-neuron explanations of human behavior are controversial and contested, and no less an authority than Steven Pinker has referred to them as “an extraordinary bubble of hype.” Meanwhile, cognitive scientist Gregory Hickock has written an exhaustive book on the subject with a title that says it all: The Myth of Mirror Neurons.

Film scholars who appeal to the mirror neuron paradigm have not engaged with criticisms of it. Hence, their neural explanations of cinema appear to be supported by a scientific consensus that is in fact lacking, and they may not be drawing on the best current science.

For example, the philosopher of film Dan Shaw maintains that “The discovery of the existence and emotive function of mirror neurons confirms that we simulate other people’s emotions in a variety of ways, even in cinematic contexts,” and he views mirror neurons as the neurophysiological foundation for cinematic empathy. Notice how Shaw makes a strong claim here by using the word “confirms.”

Yet, although Shaw writes that “it is a cliché that monkeys are good imitators,” Pinker suggests that macaques do not imitate and they have “no discernible trace of empathy.” This is despite their possession of mirror neurons. Thus, the mere presence of mirror neurons or a mirror system in a creature cannot be evidence, in and of itself, for the creature’s capacity for empathy. While it might provide one of the neural foundations for empathy or contribute to its realization in some way, much more is needed than mirror neurons or a mirror system for a creature to empathize. Their presence certainly doesn’t “confirm” that we empathize with characters in film.

It is, however, a different, equally pernicious consequence of the authority of science that I wish to highlight here using mirror neurons. The apparent authority of a scientific paradigm can lead scholars to cherry-pick and mischaracterize our artistic practices in order to fit the science. This brings us back to Gallese, one of the co-discoverers of mirror neurons, and Guerra, and their claims about camera movement.

Camera movement and mirror neurons

Gallese and Guerra argue that our mirror neurons not only simulate the emotions of film characters but also the anthropomorphic movements of the camera recording them.

We maintain that the functional mechanism of embodied simulation expressed by the activation of the diverse forms of resonance or neural mirroring discovered in the human brain play an important role in our experience as spectators. Our ability to share attitudes, sensations, and emotions with the actors, and also with the mechanical movements of a camera simulating a human presence, stems from embodied bases that can contribute to clarifying the corporeal representation of the filmic experience. [My emphasis.]

In support of their contention that the mirror neurons of film viewers simulate human-like camera movements, Gallese and Guerra cite an experiment they participated in. This measured the motor cortex activation of nineteen subjects who were shown short video clips of a person grasping an object. The action was filmed in four different ways: with a still camera, a zoom, a dolly, and a Steadicam.

“The results were positive,” Gallese and Guerra conclude. “Shortening the distance between the participant and the scene by moving the camera closer to the actor or actress resulted in a stronger activation of the motor simulation mechanism expressed by the mirror neurons” relative to the clips shot with a still camera. Moreover, the subjects rated those scenes filmed with a moving camera as more “involving.”

Gallese and Guerra rely on this single experiment to make a bold argument about the role of camera movement in the design of films and its effect on the experience of film viewers. “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” This is because “the sense of participation in the camera action is undoubtedly enhanced by the fact that its behavior is interpreted by both filmmakers and spectators according to evident and automatic anthropomorphological analogies.”

When scenes are recorded with human-like camera movements, they seem to be suggesting, our mirror neurons simulate these camera movements because they are like actions we ourselves have performed. This in turn results in a feeling of “involvement” or “participation” in the scene on the part of the film spectator.

There is much one could question about this experiment and the conclusions Gallese and Guerra draw from it. For example, if it is camera movement that elicits mirror neuron simulation which in turn gives rise to a sense of immersion, viewers should feel involved in the camera movement, not the sceneit films. Indeed, what is depicted in the scene should be irrelevant to the viewer’s feeling of involvement if it is the camera movement that gives rise to this feeling by eliciting mirror neuron simulation.

Making the art fit the science

It is, however, the theory’s cherry-picking and mischaracterization of the artistic practice of cinema that most concern me here. According to this theory, as we have seen, “the involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” The explanatory claim is that anthropomorphic camera movements, in other words those that resemble the human action of walking through space, elicit the mirror neuron simulation that gives rise to the viewer’s immersion in the film.

This is a strong claim, and if it were true it would have profound implications for both the study of film and filmmaking. It would mean that the more anthropomorphic camera movements that films contain, the more involving they would be for viewers. It would also mean that scenes filmed with human-like camera movements would be more involving than those shot with a still camera, and that scenes filmed with non-anthropomorphic camera movements would be less involving than those shot with anthropomorphic ones.

The latter is due to the mirror neuron simulation theory’s argument that we can only simulate movements we ourselves have performed. Hence, camera movements must be like ones we have executed ourselves in order for our mirror neurons to simulate them and produce the requisite sense of immersion.

Before assessing this claim, one question needs to be answered. What, exactly, is meant by involvement, participation and immersion? After all, there are a number of different kinds of possible involvement in a film.

We can be cognitively immersed in a film when we are intensely interested in the outcome of the plot or the revelations of a documentary. We can also be emotionally involved, as when we feel strong emotions toward the people or events depicted in the film. There is also aesthetic involvement when we pay close attention to and evaluate the design properties of a film. Then there’s physical or corporeal involvement, as when we are physically impacted by film techniques, such as the startle effect or bright lights and loud sounds. Doubtless there are other kinds of involvement too.

Gallese and Guerra never explicitly define what they mean by involvement, although on occasion they mention a “sensation of immersion in the spatiotemporal dimension of film.” In an earlier text they claimed that, by using the camera to mimic bodily movement, filmmakers make audiences feel that “we are inside the diegetic world, we experience the movie from a sensory-motor perspective and we behave ‘as if’ we were experiencing a real life situation.”

Personally, I am not sure what they mean by this. I have never felt immersed in the space and time of a film in the sense of somehow thinking or feeling that I am actually inside it. More importantly, it is not clear that the subjects of the experiment on which their theory is based meant spatiotemporal involvement as opposed to cognitive, emotive, aesthetic or other kinds of immersion when they rated how involved they felt in the clips they were shown. Thus, Gallese and Guerra’s experiment may provide no empirical evidence at all for their occasional references to spatiotemporal participation.

Confusingly, however, Gallese and Guerra sometimes seem to mean involvement in another sense of the term I have clarified. Regarding the brief camera movement toward the keychain in the scene from Notorious of Alicia stealing the key, they contend that “The problem that Hitchcock had to solve in this complex sequence was how to bring the spectator to an almost unbearable level of suspense.” They suggest that if Hitchcock had only used “classical editing” to film the scene, “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high.” They conclude: “This is why Hitchcock uses camera movement; it is this movement that creates the overpowering tension.”

Here, Gallese and Guerra seem to be using “involvement” in the emotive sense of feeling strong emotions such as “tension” and “suspense” about the characters and events in the scene, and they make no mention of “spatiotemporal immersion.” Either way, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence at all that it is this brief camera movement “that creates the overpowering tension” in the scene. While the camera movement is certainly effective in drawing our attention to the keys and conveying Alicia’s anxious focus on them, I conjecture that there is a far more obvious, broadly “cognitive” reason for the scene’s suspense.

This is the possibility that Alicia, with whom we sympathize, will be caught stealing the key by her husband, who is a ruthless Nazi. Gallese and Guerra, however, discount such a narrative-based explanation for the suspense. They argue that “What strikes us most in films like Notorious is Hitchcock’s almost complete indifference to the plot” and that “the state of suspense in which we find ourselves at every viewing of Notorious has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.”

Yet, according to Hitchcock biographer Donald Spoto, Hitchcock himself wrote the outline for Notorious in late 1944, and then spent three weeks closeted with Ben Hecht writing the script, which was further modified in late-night script sessions with David O. Selznick before the project was eventually sold to RKO and filming began in October 1945. While it may be true that Hitchcock tended to see the plots of his films as merely a means to creating the arresting images and eliciting the strong emotions from his audiences that truly interested him, this does not mean he was “indifferent” to plot. He spent considerable time developing his scripts, and he was keen to work with talented screenwriters such as Hecht.

Nor is it plausible that the suspense in Notorious “has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.” Indeed, suspense is usually defined as a state of anxious uncertainty about what will happen in the story. If suspense has nothing to do with the story, it is hard to know what viewers feel suspense about. In the key-stealing scene in Notorious, it is surely the case that we are anxious about the possibility that Alicia will be caught in the act of stealing the key by her husband, an event that might happen in the narrative. If not, what else might the suspense be directed at?

Of course, the suspense in this scene is not solely dependent on the story but also on the scene’s style. But there are other stylistic techniques that play a much bigger role than the camera movement in the creation of suspense in the scene. For example, Alex’s shadow is visible on his partially open door as he towels himself dry and moves around the shower room.

This activity suggests that he has finished his shower and will emerge at any second. It starts to seem more likely that Alicia will be caught stealing the key, thereby intensifying the suspense. Meanwhile, other than delaying the scene’s outcome by a few seconds, it is not clear how the camera movement toward the keychain itself intensifies the scene’s suspense.

What is happening in the narrative and what is conveyed by other stylistic techniques, such as Alex’s shadow on the door and the music on the soundtrack, are the factors that intensify the scene’s tension. It seems highly unlikely that “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high” in the absence of the camera movement, in the sense of feeling tension and suspense about the scene’s outcome. Certainly, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence to this effect.

Furthermore, as I’ve already mentioned, Gallese and Guerra’s theory at best explains our sense of involvement in the camera movement, not the scene it films. Recall that it is the camera movement itself that our mirror neurons simulate. It is unclear from their theory, therefore, how our putative feeling of immersion in the camera movement, if indeed we do feel immersed in it, can yield suspense about the concrete actions being filmed.

The category of human-like camera movement, if such a category is functionally relevant to cinema, comprises many fine-grained variations with different effects. Camera movements, for example, can elicit curiosity by making us wonder what they will reveal, as well as surprise when they come to rest on something unexpected. They can startle through their rapidity, as when swish pans suddenly disclose something off-screen, or they can uncover information at an agonizingly slow pace. They can reveal characters’ mental states through push-ins that show us that a character is concentrating hard on something, or they can hide information from us by moving away from it. They can also be aesthetically pleasing, as when we marvel at their gracefulness or the intricacy with which their movements are coordinated with those of the characters. None of these sources of the power of camera movement are explained by arguing that mirror neurons fire in response to anthropomorphic camera movements, if indeed they do.

Most broadly, as David points out in his previous entry, there is much that their theory cannot capture or explain about the power of framing. A static camera can evoke tremendous suspense, as David’s example from Hou’s Summer at Grandpa’s illustrates. It is hard to see what a tracking shot would add at such a moment.

The lessons of film history

Of course, just as damaging to the theory are the countless examples from the rich history of film of highly suspenseful, tension-filled, and in other ways involving scenes that lack anthropomorphic camera movements or that contain non-anthropomorphic ones.

In Notorious, right after the scene in which Alicia steals the key and is nearly caught by Alex, there is a crane shot in which the camera, having panned across the party in the hallway below from a first-floor landing, glides smoothly down toward Alicia talking to Alex and some guests in the hallway and ends in a close-up on her hand holding the key to the cellar.

Given that no human being could perform this movement, our mirror neurons shouldn’t be able to simulate it and produce a feeling of involvement in it. Yet, I hypothesize that, for most viewers, this camera movement creates a strong sense of cognitive, emotive, aesthetic, and other forms of engagement in the scene.

Among other things, this movement prompts us to wonder how Alicia is going to gain entry to the wine cellar without her husband noticing, thereby intensifying our sympathetic concern for her and our suspense about whether she will be caught. And in its overtness, it might make us think about Hitchcock’s choice of technique and the reasons behind it. For some, it might even induce that sense of “spatiotemporal immersion” that Gallese and Guerra mention given that it brings our perceptual perspective close to Alicia’s in the midst of the party, although I personally don’t feel this.

Either way, in this case, it cannot be due to mirror neuron simulation that we experience these forms of immersion. This is a non-anthropomorphic camera movement that human beings cannot execute themselves and therefore cannot simulate with their mirror neurons.

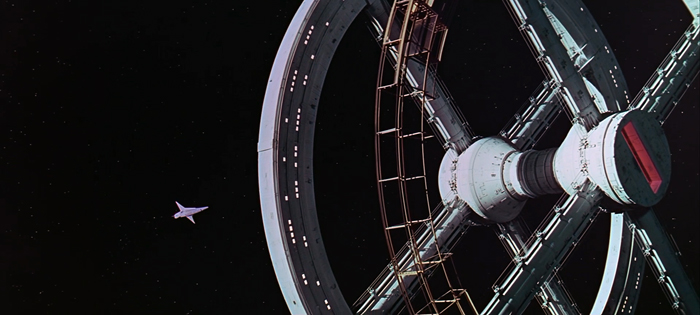

An example from a film by a different director would be the shots in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) of Dr Floyd (William Sylvester)’s ship docking with a space station while Strauss’s Blue Danubewaltz plays on the soundtrack. (See image surmounting today’s entry.) For many, the smooth camera movements through space in this sequence evoke an intense sense of weightlessness, thereby creating a physical or corporeal form of involvement in the film. Yet, very few of us have moved in space or have experienced weightlessness, meaning that our mirror neurons should not be able to simulate these camera movements.

Then there are the copious examples of involving scenes that lack camera movement. Hitchcock’s oeuvre contains many, such as the infamous shower scene in Psycho (1960), which is devoid of camera movement during the 20 seconds or so in which the stabbing of Marion Crane takes place. Another example is the highly suspenseful sequence in Strangers on a Train (1951) in which Bruno (Robert Walker) drops Guy (Farley Granger)’s cigarette lighter down a drain while he is on his way to plant the lighter at the amusement park where he murdered Guy’s wife, Miriam (Kasey Rogers). Bruno wishes to implicate Guy in the murder, and Guy, who is a professional tennis player, has guessed Bruno’s plan and is trying to complete a tennis match in time to stop him from planting the lighter. Hitchcock cuts back and forth between the tennis match and Bruno’s efforts to reach down into the drain and retrieve the lighter.

Interestingly, while there is some camera movement at the beginning of the sequence, as the suspense builds, the camera movement lessens. Hitchcock relies largely on still shots of Bruno’s grimacing face as he reaches into the grate, his hand inside the grate and the lighter below it, and the faces of the referees and spectators at the tennis match. Only the shots of Guy and the other tennis player contain a little movement when the camera slightly reframes them as they move to hit the tennis ball.

This sequence is considered one of the most suspenseful (and thereby emotionally involving) in Hitchcock’s oeuvre, yet it defies Gallese and Guerra’s prediction that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.”

So does the astonishing sequence in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) in which Horace (Herbert Marshall), having told his estranged wife, Regina (Bette Davis), of his plans to leave his fortune to their daughter, begins experiencing painful symptoms of his heart disease as she tells him how much she despises him.

Horace reaches for his heart medication but knocks over the bottle and its contents and begs his wife to fetch another bottle of medication from upstairs. She, however, sits immobile while Horace, realizing she will not help him and wants him to die, staggers around her, clinging to the wall, and stumbles upstairs before collapsing on the staircase. An agonizing long take lasting about forty seconds shows Regina in medium shot sitting while her husband, who is out of focus, moves toward the stairs, and the shot is immobile except for slight reframings to keep Horace partly visible in the shot.

This is an intensely suspenseful, emotionally involving moment as we wonder whether Horace will reach his medication in time, or Regina or someone else will take action to help him. Yet, there is no anthropomorphic camera movement to elicit our sense of involvement in the scene. On the contrary, according to many critics, it is precisely the lack of camera movement that contributes to its emotional intensity. As André Bazin noted, “Nothing could better heighten the dramatic power of this scene than the absolute immobility of the camera,” in part because it mirrors and emphasizes the “criminal inaction” of Horace’s wife, Regina, who is hoping he will fail to reach his medication and die so that she can be rid of him and claim his fortune.

Gallese and Guerra could perhaps protest that I have misconstrued their theory. Although their claim that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements” seems to suggest that anthropomorphic camera movement is both a necessary and sufficient condition for occasioning involvement in a film, they might admit that immersion can be elicited in other ways. Instead, they could allow, human-like camera movement is merely a sufficient condition for involvement, not a necessary one. When it is present, we feel immersed in films, although this is not the only route to immersion.

However, it is not difficult to think of films containing lots of camera movement of both the anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic kinds that fail to engage viewers. An example is Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), a film in which, as David Ansen of Newsweek put it, “The camera, and the actors, are always in a mad dash from here to there” (Ansen 1994). Nevertheless critics, who according to Gallese and Guerra “usually get much more excited” when camera movement is present, largely panned the film. (For what it’s worth, the film has a critics’ score of 38% and audience score of 49% on Rotten Tomatoes.) As Ansen put it:

What we get is Romanticism for short attention spans; a lavishly decorated horror movie with excellent elocution. [Branagh’s] strategy undermines itself–there’s a lot of sound and fury, but all the grand passions are indicated rather than felt. Watching the movie work itself into an operatic frenzy, one remains curiously detached: the grand gestures are there, but where’s the music? [My emphasis.]

Anthropomorphic camera movements do not, therefore, even appear to be a sufficient condition for immersion in a film, let alone a necessary one.

The way forward?

Gallese and Guerra, it seems to me, cherry-pick examples from films that appear to support their theory, and ignore obvious counterexamples even in the films they examine. They also mischaracterize scenes such as the one in which Alicia steals the keys, overlooking other evident sources of “involvement,” a term they fail to define consistently. They do, I suspect, because they are in thrall to the mirror neuron theory, and they therefore force the art to fit the theory.

None of this means that cognitivism should be abandoned and that film scholars shouldn’t be turning to science. Nor does it mean that camera movement doesn’t sometimes elicit and intensify emotions such as suspense. Moreover, neuroscience may well be able to shed light on some of the reasons why this happens, although many more experiments are needed to demonstrate this than the single one relied on by Gallese and Guerra.

But it does suggest that our engagement with the sciences should be governed by two principles.

First, when drawing on a scientific theory, it is crucial that film scholars also consider criticisms of it. Despite its authority, scientific research is typically provisional. Those of us in the humanities are not usually in a position to determine who is right in a scientific debate. So we should entertain criticisms of the scientific theory, in case they reveal pitfalls and other problems in applying the theory to cinema, or show the theory to be on far less secure ground than it may seem to be.

Second, those of us who are humanistic scholars of film should trust the knowledge we have gleaned from decades of work on the cinema. We shouldn’t simply accept conclusions that contradict this knowledge because they are supposedly scientific. We should not, in other words, be cowed by the authority of science. While we haven’t gotten everything right, most of us know from a little reflection, for example, that anthropomorphic camera movements aren’t required for greater “involvement” in a film.

Of course, we should allow for the possibility that our assumptions about these and other matters are incorrect. But given the weight of experience and knowledge behind them, the evidentiary bar should be set very high for their disconfirmation by empirical scientific research.

Thanks to Malcolm for all his work in preparing this version of his paper for our blog. Another essay of his along these lines is “Can Scientific Models of Theorizing Help Film Theory?” in Philosophy of Film: Introductory Texts and Readings, ed. Angela Curran and Tom Wartenberg (Blackwell, 2004), 21-32

Quotations from Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra’s Empathic Screen come from pp. 68, 111, 91, 94, and 114. Their claims about Notorious are found on pp. 53-58. The quotation from their earlier piece can be found in “Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies,” Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image (2012) 3: 188.

The crucial experiment is documented in Katrin Heimann et al., “Moving Mirrors: A High-Density EEG Study Investigating the Effect of Camera Movements on Motor Cortex Activation during Action Observation,” The Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience (2014), 26,9: 2087-2101. with the discussion of involvement coming on p. 2097. The Marco Iacobobi citation comes from Mirroring People: The New Science of How We Connect with Others (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 5.

Pinker’s remarks about mirror neurons and empathy are to be found in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Penguin, 2011), 577. The quotations from Dan Shaw are from “Mirror Neurons and Simulation Theory: A Neurophysiological Foundation for Cinematic Empathy,” in Current Controversies in Philosophy of Film, ed. Katherine Thomson-Jones (Routledge, 2016), 148, 151.

André Bazin discusses The Little Foxes in “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work, ed. Bert Cardullo (Routledge, 1997) 3, 4. A blog entry here supplies further thoughts on the famous scene, which DB also analyzes in On the History of Film Style.

Donald Spoto discusses Hitchcock’s working methods in The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Da Capo, 1999; Centennial Edition), 284-287. David Ansen’s strictures on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein appeared in “Monster Mush,” Newsweek (6 November 1994). More on Notorious is here.

During the current health crisis, Berghahn has made all issues of Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind freely available. Several articles over the years debate issues around cognitive film theory and brain-based explanations of media effects. Malcolm Turvey has made many contributions to Projections; see especially his book review here.

2001: A Space Odyssey.