When Hollywood ruminates: Calm after THE MORTAL STORM

Sunday | March 1, 2020The Mortal Storm (1940).

DB here:

We don’t usually think of classic studio cinema as particularly contemplative. But many films open up spaces for quiet reflection on what we’re seeing, or have seen. In the 1940s, that tendency owed a good deal to the ways that Hollywood became, to put it roughly, more novelistic.

Movies had been based on novels for many decades, but in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, I claimed something more specific. I think that many 1940s filmmakers became more acutely aware of sound film’s capacities for manipulating time and point of view. These are novelistic techniques par excellence, distinctly different from the largely “theatrical” conceptions of presentation that we find in most studio cinema of the 1930s. Films turned inward, probing perceptions, memories, and dreams. If you need a storytelling twist, one journalist cracked, just call it psychology, and it will get by.

Of course, there are plenty of precedents for time and POV shifts in early decades. Still, I wanted to show that between 1939 and 1952 many major options emerged and were developed in ambitious directions. The results left a legacy. Today, when flashbacks are common and we easily grasp elaborate shifts in viewpoint, our films rework the possibilities refined and consolidated in the 1940s.

One stretch of the book considered some films from early-to-mid 1940 that offered glimpses of innovations we’d see in later years. Married and in Love, One Crowded Night, Stranger on the Third Floor, and Edison, the Man previewed techniques that would dominate the next decade. Particularly chock-full of storytelling ideas, I argued, was Our Town, a daring transposition of 1930s theatrical devices into the key of cinema.

Missing from my roster, though, is The Mortal Storm, a film that went into release in June of 1940. I had neglected to rewatch it when writing the book. A couple of weeks back I caught up with it during a screening at our Cinematheque. Restored by UCLA, it fairly shimmered off the screen.

How could I not have remembered the stunning closing sequence? It’s a bundle of narrative strategies that would get elaborated in the years to come. And it achieves its effect from being somber, slow, and based on human absence. In this epilogue, the movie pauses to think.

To talk about this passage and its counterparts, I have to parade plenty of spoilers. Sorry. But at least you get video.

Emptying the nest

The Mortal Storm.

The plot starts in Germany at the moment of Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933. Elderly Viktor Roth is a much-loved Jewish professor of medicine. His household includes his stepsons Otto and Erich, his wife Emilia, and their daughter Freya. Two other young men are close to the family: Fritz, who aspires to marry Freya, and Martin, a farm boy training to be a veterinarian.

Otto, Erich, and Fritz become enthusiastic Nazis, but Freya draws closer to Martin, who quietly resists the growing bigotry in their small town. Professor Roth is arrested and killed. Martin and Freya, now deeply in love, try to escape by ski to Austria. A squad of soldiers, under Fritz’s direction, fires on them. Freya is killed.

In the crucial scene, Fritz returns to the family home to tell Otto and Erich.

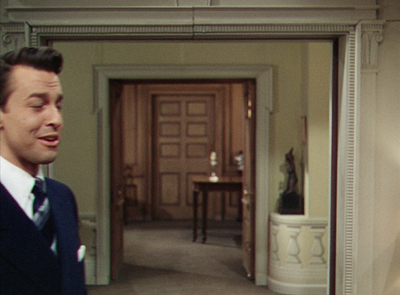

The sequence blends several narrational choices. Most obvious is the camera movement that seems to drift off on its own. It is, we might say, semi-subjective. It suggests Otto’s slow walk through the now-empty home, but it isn’t clearly marked as his optical POV. The opening stretch of the shot shows him pacing more or less obliquely to us, before the camera pans and tracks to the table and beyond.

The framing insistently keeps Otto offscreen. Only the sound of his footsteps and pauses suggest that he’s present, off left or behind us, at each station of the shot.

As the camera drifts along, we get auditory flashbacks to earlier scenes, three at the table, and one echoing the Professor at his lectern. Flashbacks are characteristic features of 1940s cinema, and purely auditory ones will come into prominence, as in The Fallen Sparrow (1943). Since we’ve seen the action these flashbacks evoke, they’re as much flashbacks for us as for Otto. Indeed, Otto has been a minor character in the story. His walk triggers them, but his absence from the frame makes it easier for us to project our memories onto these spaces.

The transition among the flashbacks prepares for Otto’s defection. The voice shifts from Freya, whose death Otto is grieving, to the men challenging authority. We hear Professor Roth urge youth forward, and Martin advocating peace and free thought. These later moments seem to crystallize Otto’s change of heart. Dwelling a bit on the statuette of Youth carrying the torch of knowledge suggests that Otto may become inspired to take up his father’s commitment to humanism.

At the climax of the shot, the camera frames the staircase (another icon of 1940s cinema) and starts to back up. This can hardly be Otto’s optical viewpoint. The rapid footsteps suggest that he has left the house by striding out, as it were, behind us. The sound of a closing door confirms our inference. He has left us behind.

As he does in the final moments, when Otto’s flight is depicted as footprints in the snow. Perhaps, now that he has become revolted by the cruelty of Fritz and the Nazi regime, he will take up resistance in Martin’s spirit.

Accompanying the shots of the footprints is the voice-over narrator whom we heard at the film’s start. (Such narrators proliferate in 1940s movies.) His speech, from a poem called “The Gate of the Year,” echoes the visuals: a man “at the gate,” the prospect that one may “tread safely into the unknown.” In giving up Nazism, Otto is giving up home.

The camera tilts up to show the empty house. The snow-encased home is quite different from the bustling view we saw at the film’s start, when the postman delivered gifts for Professor Roth.

Hitler has destroyed the family. Still, as the snow buries the footprints, the narrator urges that divine guidance can provide safety for Otto’s escape, and perhaps a decision to fight Nazism.

We don’t normally think of MGM as a hotbed of cinematic innovation in the studio years. But the company had its moments (here and there), and this is one of them. The Mortal Storm‘s play with time (flashbacks, the solemn duration of the house tour) and viewpoint (Otto triggering some bits of remembered dialogue) resembles what we might get in a psychologically slanted novel of the time. We’re given a few minutes to breathe deeply and think about what we’ve seen, and to build up expectations about what Otto may do.

The house as memory vessel

The Miniver Story (1950).

One section of Reinventing Hollywood analyzes Enchantment (1948), a film narrated by a house. The house presents itself as a cozy repository of the memories of several generations. More generally, houses are powerful images in 40s films; think of Tara, Manderly, the estate in Dragonwyck, and the Gothic mansions of Jane Eyre, Gaslight, and The Spiral Staircase. Often they’re presided over by ominous portraits, as Steven Jacobs and Lisa Colpaert have shown.

One lesser-known example is House of Strangers (1949), directed by Joseph Mankiewicz. This story of an Italian immigrant who has become the head of a big bank is framed by his son Max returning to their massive home. The bulk of the film is given in flashback, but the flashback is launched by a wandering camera accompanied by “M’apparti tutt’amor” (from the opera Martha) playing on the phonograph. After a trip up the stairs we are taken via dissolve to the patriarch singing it in his bath.

The plot’s central section treats the lyric (“You all seem to love me”) with doubled implication: Gino’s reckless loans endear him to his customers, but his sons resent his power over them. The long flashback ends at Gino’s funeral, passing from the portrait in the past to the phonograph and to his son Max, brooding under the looming picture.

The huge Minafer mansion is practically a character itself in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). One of Welles’ late script versions envisioned a climax in which George, distraught by the shabbiness of their neighborhood, would pass numbly through the house, and our sense of it would be given through his eyes.

145 FULL SHOT of the Amberson Mansion, seen from behind George who is standing in front of camera. He starts walking toward the mansion. CAMERA FOLLOWS, moving faster than he does and soon is so close to him that his body creates a dark screen for a DISSOLVE TO:

146 CAMERA is on the steps of the Amberson Mansion, MOVING up to the door and STOPPING. George’s hands enter the scene, insert a key in the lock, turn it —

147 On the Narrator’s words, “move out” the door opens and CAMERA MOVES thru it into the house.

MOVING SHOT as CAMERA WANDERS SLOWLY about the dismantled house — past the bare reception room; the dining room which contains only a kitchen table and two kitchen chairs, up the stairs, close to the smooth walnut railing of the balustrade. Here CAMERA STOPS for a moment, then PANS down to the heavy doors which mask the dark, empty library. HOLD on this for a short pause, then CAMERA PANS back and CONTINUES, even more slowly, up the stairs to the second floor hall where it MOVES up to the closed door of Isabel’s room. The door swings open and we see Isabel’s room is still as it always has been; nothing has been changed. FADE OUT

This passage is strikingly similar to what we see in The Mortal Storm. True, the cues for George’s optical viewpoint are more explicit than what Borzage gives us for Otto. But Welles is subtler along another dimension. He counts on our remembering earlier scenes without benefit of auditory flashbacks. The camera revisits the reception area we saw during the ball, the dining room where George challenged Eugene Morgan, and the staircase where George and Fanny quarreled, before coming to rest in Isabel’s room, where we saw her waste away and die. We are asked to supply our own flashbacks.

Some of this POV passage might have been filmed, but it wasn’t retained in Welles’ final version, even before RKO’s mangling. In the film as we have it, only Welles’ lead-in and conclusion remain. The narrator supplies a moving-camera montage, as George registers the changes in Amberson Avenue.

The street sequence ends in darkness and tracks back from George kneeling at the bed begging forgiveness. The fact that the shot starts from his darkened head reinforces the subjectivity of the montage.

Welles’s handling is novelistic in the sense of wrapping a character’s flowing impressions inside an omniscient verbal commentary using free indirect discourse (“Tomorrow they were to move out”). George’s moments of rueful meditation are moments for us as well.

Like the narrator that closes The Mortal Storm, this voice is external to the story world. But the same house-haunting effect can be achieved by a narrator who lives in that world. Coupled with the wandering camera, this can turn our view of a scene in the present into a view of the past–or of an eternal future.

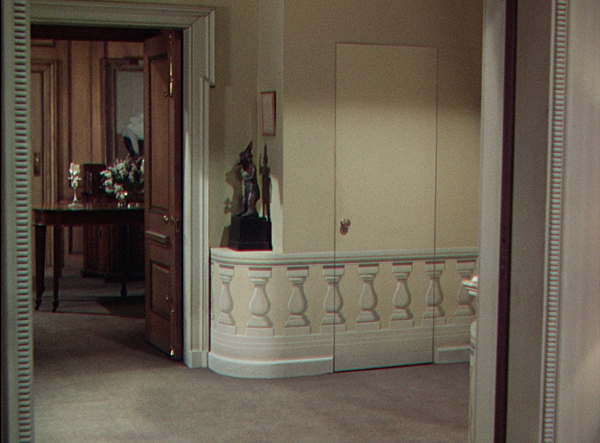

The example I have in mind is from The Miniver Story (MGM again, 1950). In Reinventing, I analyze a sequence that creates layers of time: Clem Miniver’s voice-over in our present, an image of he and Kay in the past, and references in the commentary to periods still earlier than what we see. (The clip of this sequence is online here.) At the end of the film, after the Minivers have married off their daughter Judy to Tom, they must face Kay’s impending death from cancer.

The final sequence shifts from the day of the wedding to a kind of timeless realm in which Kay’s spirit lives on. Again, camera movement suggests an invisible presence.

By 1950, we’ve had several permutations. The camera wanders without verbal narration (music alone in House of Strangers). It does so with auditory flashbacks (The Mortal Storm). It does so with a nondiegetic (external) narrator (The Magnificent Ambersons). And it does so with a diegetic (story-world) narrator (The Miniver Story). I try to show in the book that 1940s filmmakers swiftly expanded, even exhausted, menu options involving many storytelling techniques.

Trust Hitchcock to give us yet another variant, and in a tour de force at that.

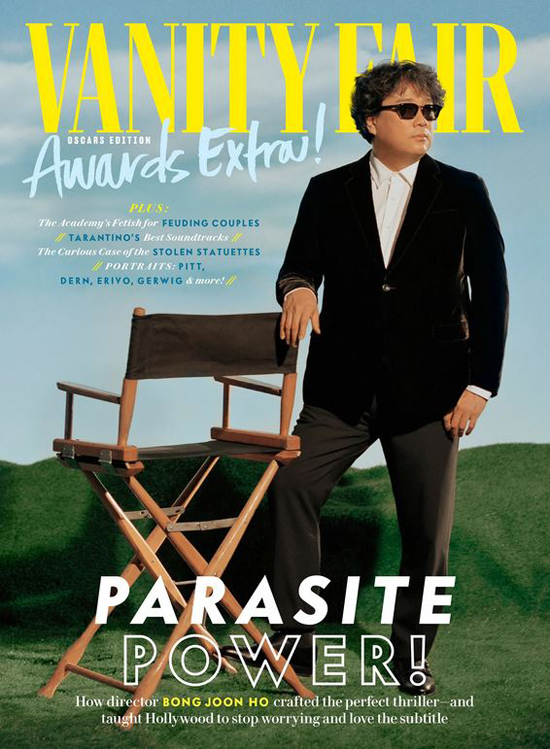

Enough rope

In the eleven shots of Rope (1948), set almost completely in an apartment, the camera’s peregrinations are usually motivated by character movement or simple track-ins and track-outs. At the climax, though, the camera cuts loose. Sort of.

Brandon and Phillip have strangled their friend David and hidden his body in a chest in their living room. They’ve ghoulishly used the chest as a buffet table for their afternoon party. After the party, one guest, their prep school teacher Rupert Cadell, has returned. He suspects that something bad has happened to David. Rupert challenges the pair and sketches out how they might have murdered their friend.

His reconstruction isn’t wholly correct. David wasn’t bludgeoned, and apparently the armchair played no role. What’s fascinating is that the camera supplies a hypothetical, virtual flashback. As in our earlier examples, David becomes an invisible guest, summoned up by the mobile frame.

The camera traces out the action Rupert posits, emphasizing the hall closet (where Rupert earlier discovered David’s hat) and edging eventually toward the chest. At that point Brandon steps in, with his hand tensing around the pistol in his pocket. He stands in front of the drinks table.

That’s the climax of the shot. Cut to a shot of Rupert. He seems to intuit that he should avoid mentioning the chest, so he proposes that they might have carried the body out of the building. As the camera traces out that possibility, Brandon steps back into the frame to confront Rupert.

Here I think Hitchcock made a mistake. At the end of the first shot, Brandon and his pistol are quite close to Rupert, near the drinks table. But in the followup shot, he’s not visible when the camera pans left past the table to enact the scenario Rupert is considering. Brandon would have had to skip backward like the Road Runner to get as far away as he is when he steps back into the frame in the second shot.

Still, the important effect is the representation of Rupert’s thinking. Goaded by Brandon, he ponders how the crime might have been committed, and the camera carves into space to reveal the scheme he conjures up. A sort of flashback? Yes, but an unreliable replay, left largely to our imagination. Semi-subjective? Yes, since when we cut to Rupert he seems to be staring down at the chest. Yet the camera is too free-ranging to be purely Rupert’s optical POV. He’s not moving around, as Otto is in the Mortal Storm sequence.

In this most “theatrical” of movies, Hitchcock manages to give us a verbal-visual flow that is something like a cinematic equivalent of the novelist’s conditional perfect tense. If Brandon and Phillip had killed David, they could have done it this way. The camera enacts a speculative train of thought. Call it psychology.

One thing I shouldn’t ever forget: Hollywood in the Forties is a booming rush of visual, auditory, and narrative ideas. In the approximately 5,655 features released in the period I marked off, there are surely many other startling instances of creative craft. I’ll keep looking.

Thanks as ever to our Wisconsin Cinematheque for fine programming under the auspices of Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser and excellent projectionist Roch Gersbach. Thanks as well to Joe McBride for sharing material on The Magnificent Ambersons. More on Ambersons can be found here and here.

The Mortal Storm‘s “novelistic” final moments owe nothing to its source, Phillis Bottome’s The Mortal Storm (1938). An earlier version of my ideas about Enchantment are here.

Chapters 4 through 6 of Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood offer a careful survey of creative choices facing filmmakers of the period, along with explications of their “practical theories” about cinematography. After writing this entry, I learned that Patrick has also made a fine video essay on the Ambersons sequence.

For earlier blogs on related subjects, see the category 1940s Hollywood.

PS 2 March 2020: Patrick Keating reminds me of another 1940 release I should have mentioned: Hitchcock’s Rebecca. When Maxim narrates his confrontation with Rebecca, the camera moves autonomously to “replay” the scene. It anticipates my Rope example, except that Maxim is recounting what really happened, while Rupert is sketching out his (partially inaccurate) reconstruction of David’s death. Still, though, it’s another variant on an emerging pictorial convention. Thanks, Patrick!

PS 2 March 2020, later: Thanks also to John Belton, who writes to remind me not only of the Rebecca scene but a comparable camera movement in Under Capricorn. Crowdsourcing works.

Rope (1948).