Friday | February 21, 2020

Kristin here:

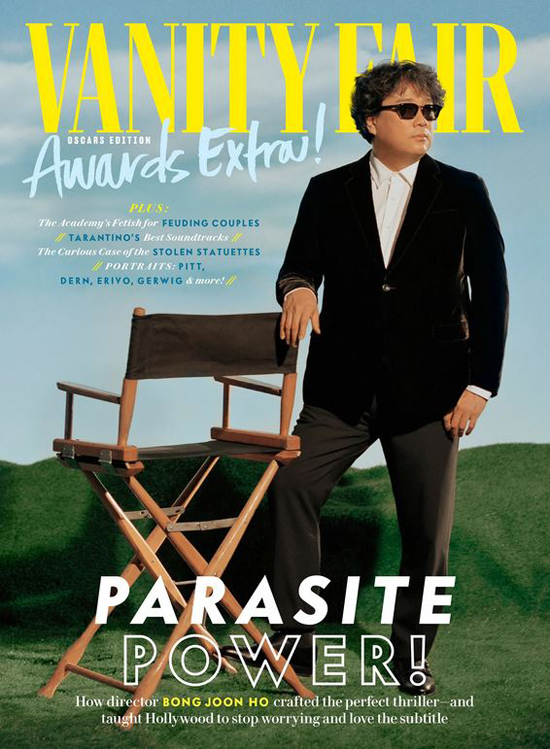

It seems like anyone writing for an online or print periodical, whether media-oriented or not, is searching for some sort of hook on which to hang an article about Parasite and Bong Joon Ho. Some of these are a bit of a stretch, others are a bit ephemeral but interesting. All testify to the surprisingly broad interest in a relatively little-known director of the first foreign-language film ever to win the Best Picture Oscar.

Some of this burst of coverage undoubtedly stems from the fact that relatively few people know anything about Bong. Predictably there are many quick overviews of his career to catch people up, as well as plenty of interviews and of where-you-can-stream-Bong’s-films guides.

Here I offer a some links to a fair sampling of some of the less predictable pieces that I have run across. Some are quite bemusing. A few were published before the February 9 Academy Awards ceremony, but the flood has, not surprisingly, come after it.

Such pieces tend to fall into categories.

Items of Mise-en-scene

People are fascinated by the Parks’ gorgeous (at least on the surface) house and yard. Back on October 31, 2019, Architectural Digest, of all places, published an interview with Bong about the set. This is surely one of the most prestigious of non-media outlets to publish on the film. After the Oscars, The Guardian, which has diligently published on various aspects of the film (see bottom), caught up and ran a piece about the set being the “real star” of the film and considering it from a genre point of view.

The mysterious “viewing stone” has been discussed. The Guardian again (see bottom line of bottom image), on February 17, ran a story entitled “Built on rock: the geology at the heart of Oscars sensation ‘Parasite.'”

The Translator

Everybody seems to be enchanted by Sharon Choi, who has accompanied Bong internationally during the long awards season from Cannes to the Oscars. On February 10, Buzzfeed reported, “There’s a Ton of Love and Memes for the interpreter of ‘Parasite’ director Bong Joon Ho.” Sure enough, all over social media there are people gushing about her (above, from the Buzzfeed story).

On February 18, a Variety headline trumpeted, “Bong Joon Ho Interpreter Sharon Choi Relives Historic ‘Parasite’ Awards Season in Her Own Words (EXCLUSIVE).” Choi had, the story reveals, turned down “hundreds of interview requests” before allowing Variety to print her story. In fact, there are interviews with Choi available on the internet, but the Variety story is not an interview. It’s a memoir by Choi in which she recalls the awards season.

Meta

There are articles about the popularity of Parasite and Bong.

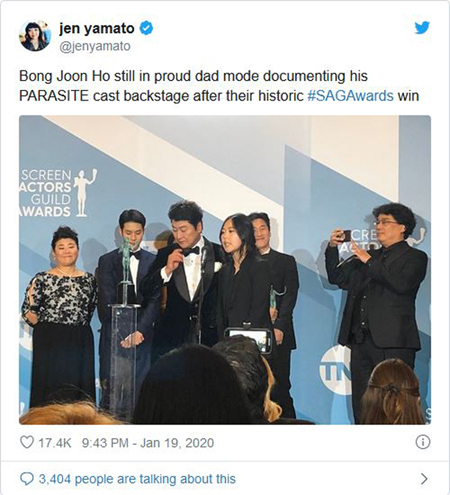

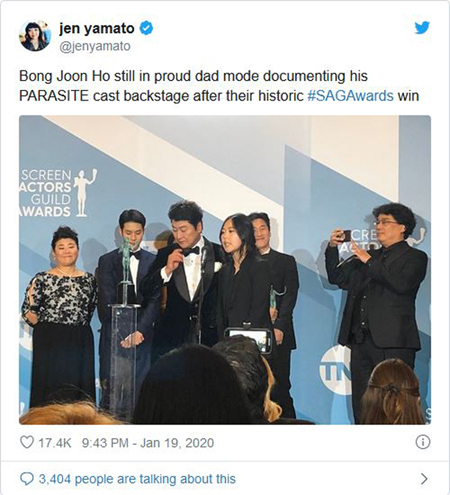

On January 20, into awards season but before the Oscars, Morgan Sung posted a piece on Mashable: “Parasite director Bong Joon Ho became a proud dad meme.” On social media, people were posting photos of Bong taking “proud dad” photos of his cast and crew getting awards (above). Note the number of likes and people “talking about this,” plus the presence of Sharon Choi in the group. The Mashable piece presents several more such snips.

Two days after the Oscar nominations were announced, on January 15 Junkee’s Joseph Earp posted about “Bong Joon-Ho, Viral Superstar,” proposing that Bong has become one of those rare directors who becomes a brand in himself. He picks up on Quentin Tarantino’s remark that Bong could become the new Spielberg.

On February 19, the livemint site reported gleefully that the day after the Oscars saw a 857% surge in searches on “Parasite.” This as opposed to 117% for 1917 and 132% for Jojo Rabbit. As the author remarks, “Bong Joon-ho’s tragicomedy thriller has been sweeping all awards and cleaning up at the box office, and people have not been able to stop talking (or searching) on Google.”

And why? “Search for director Bong Joon-ho increased for not only being the mastermind behind the film but also for his quirky sense of humour.”

I suppose the blog entry that you are now reading falls into this category as well. (And then there are our earlier comments.)

Lessons to be learned

On February 10, one of the odder stories I’ve seen went up on CNBC’s “Make It” page entitled: “‘Parasite’ director says his success is due to ‘a very simple lifestyle,’ not meeting a lot of people.” Why a business-oriented website would consider a South Korean film director’s lifestyle relevant to people aspiring to make a lot of money is anyone’s guess. Clearly CNBC was not able to get an interview with Bong so soon after the awards ceremony. Instead, the insights are derived from an article in the British Telegraph (behind a paywall). That piece is also dated February 10, and since it’s a review (albeit a late one), one must presume that its author had interviewed Bong earlier or derived his information from yet another source.

The Guardian (yet again) ran a story on February 18 headlined “Trust your nose: what rich people can learn from Parasite.” This turns out to be a satirical piece, including such tips as not buying a huge coffee table that intruders can hide under without being noticed.

This ‘n’ that

Even a periodical devoted to cuisine found a way to work in a story. On February 10, the day after the awards, Eater Los Angeles ran a story, “Oscar-Winning ‘Parasite’ Cast Parties Until 5 in the Morning at LA Koreatown Restaurant.” We learn, among other things, that “Bong Joon-ho hadn’t eaten anything all day and was so famished that the restaurant cooked up galbi jjim (braised short ribs), eundaegu jorim (braised spicy black cod), galbi (grilled short ribs), bibimbap, and seafood tofu pancakes for him and the cast.”

On February 15, Indiewire‘s Anne Thompson took us “Behind the Scenes of Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-Winning PR campaign.” Behind the scenes is publicist Mara Buxbaum, seen above with Bong. To Bong’s left is presumably Sharon Choi, who, Thompson tells us, is writing a book about her experiences as Bong’s interpreter.

I suppose the Parasite fever really does result in part from the fact that this is the first time that a foreign-language film has won a best picture Oscar. It’s probably also to a considerable extent the fact that Bong is a charming person, modest, humorous, straightforward, and very talented, and he comes across as such in his acceptance speeches and interviews. People want to know more about him, as is suggested by looper’s February 12 piece on unknown facts about Bong. If they want to know what his favorite films are and maybe watch them, they can read No Film School’s “25 Favorite Films of ‘Parasite’ director Bong Joon Ho” (February 7).

The only people who dislike Parasite and presumably its maker seem to be President T***p and his gormless fans. On February 20, he decried the awarding of the best-picture Oscar to a foreign film:

And the winner is… a movie from South Korea! What the hell was that all that about? We’ve got enough problems with South Korea, with trade. On top of that, they give them the best movie of the year. Was it good? I don’t know. Let’s get Gone With the Wind back, please? Sunset Boulevard. So many great movies.

I shan’t try to unpack the levels of ignorance and misunderstanding jammed into that passage, which was cheered by many who had never heard of Parasite and had no idea what he was going on about. It does make me pause at the notion of T***p watching Sunset Blvd., if indeed he has, and that he seems to think re-released films are eligible for Oscars decades after they were made. I’ve got to believe he at least knows that Gone with the Wind and Sunset Blvd. have already been “gotten back” and are easily available for viewing in numerous formats. The point though, is that even he has a vague notion that Parasite (or, since he doesn’t know the title, “a movie from South Korea”) is good copy.

Two Parasite items on The Guardian’s February 18 film alert.

Posted in Awards, Directors: Bong Joon-ho, Internet life |  open printable version

| Comments Off on PARASITE fever open printable version

| Comments Off on PARASITE fever

Monday | February 10, 2020

Bong Joon-ho and team accept Oscar. Photo: New York Times.

DB here:

The big news is that Bong Joon-ho has pulled off a coup. Parasite won four major Academy Awards, including Best Picture–a first for a foreign-language title.

Throughout awards season he was his bemused, genial self, and at the big ceremony he charmed everyone with his easygoing generosity toward Scorsese, Tarantino, and others. He went beyond the standard appreciation for the other nominees by saying something too seldom said at this ceremony of superficial self-congratulation: What matters is cinema, from whenever and wherever.

We’ve been supporting Bong’s work since the first days of this blog, and it was thrilling to see his triumph last night. In homage, we’ve posted some earlier encounters with Bong on our Instagram feed.

Just as exciting were the awards given to another FoB (Friend of the Blog), James Mangold. Years ago I wrote about a visit to the studio where Donald Sylvester and his team were preparing sound for 3:10 to Yuma. What a pleasure to see his work acknowledged with an Oscar. I like Ford v. Ferrari a lot, and much of its impact comes from its sound design and its picture editing (which snagged another Oscar last night, this one to Michael McCusker and Andrew Buckland). Congratulations as well to Mr. Mangold, a fine director.

Usually I’m an Oscar cynic, and not just because forgettable pictures too often claim the top honors and masterpieces are ignored. I had many favorites in the race this year, but I’m happy that filmmakers who have worked as hard to make strong, resonant genre pictures got acclaim this time around. Usually I’m an Oscar cynic, and not just because forgettable pictures too often claim the top honors and masterpieces are ignored. I had many favorites in the race this year, but I’m happy that filmmakers who have worked as hard to make strong, resonant genre pictures got acclaim this time around.

Less crowded but a big deal for us was another ceremony, held last Friday. Then our colleague Kelley Conway, another FoB, received the Chevalier d’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government. You know, the same award given to Philip Glass, Tina Turner, Cate Blanchett, Ang Lee, Mia Hansen-Löve, Mads Mikkelson, Sylvia Chang, et al. It was a swell get-together, overseen by Dean Susan Zaeske and conducted by Guillaume Lacroix, the French Consul General for the Midwest.

It was a great moment for us and our department. Kelley’s work includes books on the singer in French films of the 1930s, on Agnès Varda, and in progress, a study of French film culture after World War II. She has also guest-blogged for us (here and here and here).

Score another point for Cinema.

Finally, another big event, which took place weekend before last. Our Cinematheque screened Béla Tarr’s legendary Sátántangó. When we showed it last, intrepid projectionist Jared Lewis handled all those reels. This time, no-less-intrepid projectionist Mike King had to massage a DCP.

In that 2006 screening, there were maybe two dozen people. This time, despite freezing cold, there were over 100. And instead of that number dwindling in the course of the day, the audience actually grew. People came in at the middle and they stayed.

See? It’s just cinema being Cinema.

Thanks to our Cinematheque for its excellent programming, and a special thanks to Tony Rayns, who brought Bong to Vancouver many years ago and enabled me to meet him. Tony has been an untiring supporter of young Asian talent, and our sense of modern cinema owes a great deal to his championing directors in their formative years.

For more thoughts on Béla Tarr, go here.

Tony Rayns and Bong Joon-ho, Hong Kong 2014. Photo by DB.

Posted in Directors: Bong Joon-ho, Directors: Mangold, Hollywood: Artistic traditions |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Awards! and a very long movie open printable version

| Comments Off on Awards! and a very long movie

Friday | January 31, 2020

DB here:

Busy times! I’ve gone back to teaching this semester, and we’re revising Film History: An Introduction. So we’ve been kept from posting as often as we’d like. For the moment just let me signal the newest additions to our Observations series on the Criterion Channel.

In recent installments, Kristin offers an analysis of how film technique suppresses and reveals story points in Jane Campion’s An Angel at My Table. A free extract is here.

Jeff Smith traces how mise-en-scene techniques, especially settings, yield feminist implications in Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career. Sample it here.

This month, as you see above, I’ve offered a consideration of Vampyr as an experimental film. Again, you can see a clip.

Thanks to the people who’ve told us they enjoy our offerings, now running for nearly three years, longer than Joanie Loves Chachi. Thanks as well as to the group that makes it possible: Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Erik Gunneson, and the rest of the team in Madison and Manhattan.

With the Channel sponsoring an ambitious seventeen-film Burt Lancaster series, you might check out this entry on Brute Force.

Posted in Criterion Channel, Directors: Dreyer, Film comments, Film technique: Cinematography, Film technique: Staging, National cinemas: Australia |  open printable version

| Comments Off on VAMPYR and more on the Criterion Channel open printable version

| Comments Off on VAMPYR and more on the Criterion Channel

Friday | January 31, 2020

Director Chris Butler: “Well, I’m flabbergasted!” with producer Arianne Sutner.

Kristin here:

The Oscars are looming large, with the presentation ceremony coming up February 9. But did they ever really go away? As I’ve pointed out before, Oscar prediction has become a year-round obsession for amateurs and profession for pundits. I expect on February 10 there will be journalists who start speculating about the 2020 Oscar-worthy films. The BAFTAs (to be given out a week before the Oscars, on February 7) and Golden Globes have also become more popular, though to some extent as bellwethers of possible Oscar winners. The PGA, DGA, SAG, and even obscure critics groups’ awards have come onto people’s radar as predictors.

How many people who follow the Oscar and other awards races do so because they expect the results to reveal to them what the truly best films of the year were? How many dutifully add the winners and nominees to their streaming lists if they haven’t already seen them? Probably quite a few, but there’s also a considerable amount of skepticism about the quality of the award-winners. In recent years there has arise the “will win/should win” genre of Oscar prediction columns in the entertainment press. It’s an acknowledgement that the truly best films, directors, performers, and so on don’t always win. In fact, sometimes it seems as if they seldom do, given the absurd win of Green Book over Roma and BlacKkKlansman. This year it looks as if we are facing another good-not-great film, 2017, winning over a strong lineup including Once upon a Time in … Hollywood, Parasite, and Little Women.

Still, even with a cynical view of the Oscars and other awards, it’s fun to follow the prognostications. It’s fun to have the chance to see or re-see the most-nominated films on the big screen when they’re brought back to theaters in the weeks before the Oscar ceremony. It’s fun to see excellence rewarded in the cases where the best film/person/team actually does win. It was great to witness Laika finally get rewarded (and flabbergasted, above) with a Golden Globe for Missing Link as best animated feature. True, Missing Link isn’t the best film Laika has made, but maybe this was a consolation prize for the studio having missed out on awards for the wonderful Kubo and the Two Strings and other earlier films.

It’s fun to attend Oscar parties and fill out one’s ballot in competition with one’s friends and colleagues. On one such occasion it was great to see Mark Rylance win best supporting actor for Bridge of Spies, partly because he deserved it and partly because I was the only one in our Oscar pool who voted for him. (After all, I knew that for years he had been winning Tonys and Oliviers right and left and is not a nominee you want to be up against.) Sylvester Stallone was the odds-on favorite to win, and I think everyone else in the room voted for him.

Oscarmetrics

Pundits have all sorts of methods for coming up with predictions about the Oscars. There’s the “He is very popular in Hollywood” angle. There’s the “It’s her turn after all those nominations” claim. There are the tallies of other Oscar nominations a given title has and in which categories. And there is the perpetually optimistic “They deserve it” plea. Pundits have all sorts of methods for coming up with predictions about the Oscars. There’s the “He is very popular in Hollywood” angle. There’s the “It’s her turn after all those nominations” claim. There are the tallies of other Oscar nominations a given title has and in which categories. And there is the perpetually optimistic “They deserve it” plea.

For those interested in seeing someone dive deep into the records and come up with solid mathematical ways of predicting winners in every category of Oscars, Ben Zauzmer has published Oscarmetrics. Having studied applied math at Harvard, he decided to combine that with one of his passions, movies. Building up a huge database of facts from the obvious online sources–Wikipedia, IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, the Academy’s own website, and so on–he could then crunch numbers in all sorts of categories (e.g., for supporting actresses, he checks how far down their names were in the credits).

An early test of the viability of the method came in the 2011 Oscar race, while Zauzmer was still in school. That year Viola Davis (The Help) was up for best actress against Meryl Streep (The Iron Lady). Davis was taken to be the front-runner, but Zauzmer’s math gave Streep a slight edge. Her win reassured Zauzmer that there was something to his approach. His day job is currently doing sports analytics for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Those like me who are rather intimidated by math need not fear that Oscarmetrics is a book of jargon-laden prose and incomprehensible charts. It’s aimed at a general public. There are numerous anecdotes of Oscar lore. Zauzmer starts with Juliet Binoche’s (The English Patient) 1996 surprise win over Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) in the supporting actress category. Bacall was universally favored to win, but going back over the evidence using his method, Zauzmer discovered that even beforehand there were clear indications that Binoche might well win.

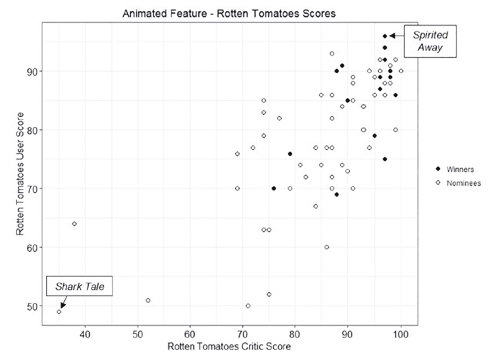

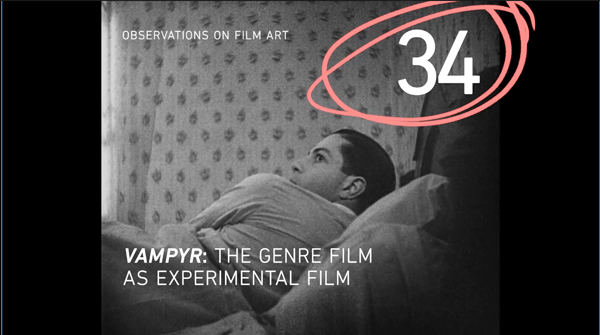

Zauzmer asks a different interesting question in each chapter and answers it with a variety of types of evidence. The questions are not all of the “why did this person unexpectedly win” variety. For the chapter on the best-animated-feature category, the question is “Do the Oscars have a Pixar bias?” It’s a logical thing to wonder, especially if we throw in the Pixar shorts that have won Oscars. Zauzmer’s method is not what one might predict. He posits that the combined critics’ and fans’ scores on Rotten Tomatoes genuinely tend to reflect the perceived quality of the films involved, and he charts the nominated animated features and winners in relation to their scores.

The results are pretty clear, in that Spirited Away is arguably the best animated feature made in the time since the Oscar category was instituted in 2001. In fact, I’ve seen it on some of the lists of the best films made since 2000, and it’s not an implausible choice either way. Shark Tale? I haven’t seen it, but I suspect it deserves its status as the least well-reviewed nominee in this category. The results are pretty clear, in that Spirited Away is arguably the best animated feature made in the time since the Oscar category was instituted in 2001. In fact, I’ve seen it on some of the lists of the best films made since 2000, and it’s not an implausible choice either way. Shark Tale? I haven’t seen it, but I suspect it deserves its status as the least well-reviewed nominee in this category.

Using this evidence, Zauzmer zeroes in on Pixar, which has won the animated feature Oscar nine times out of its eleven nominations. In six cases, the Pixar film was the highest rated among that year’s nominees: Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, WALL-E, Up, Inside Out, and Coco.

In two cases, Pixar was rated highest but lost to a lower-rated film: Shrek over Monsters, Inc., and Happy Feet over Cars. I personally agree that neither Shrek nor Happy Feet should have won over Pixar. (Sorry, George Miller!)

Zauzmer finds three cases where Pixar did not have the highest rating but won over others that did: Ratatouille beat the slightly higher-rated Persepolis, Toy Story 3 should have lost to the similarly slightly higher-rated How to Train Your Dragon, and Wreck-It Ralph was way ahead on RT but lost to Brave. Wreck-It Ralph definitely should have won, and the sequel probably would have, had it not been unfortunate enough to be up against the highly original, widely adored Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse.

The conclusion from this is that the Academy “wrongly” gave the Oscar to Pixar films three times and “wrongly” withheld it twice. As Zauzmer points out, this is “certainly not a large enough gap to suggest that the Academy has a bias towards Pixar.” This is pleasantly counterintuitive, given how often we’ve seen Oscars go to Pixar films.

Oscarmetrics offers interesting material presented in an engaging prose style, more journalistic than academic, but thoroughly researched nonetheless.

In his introduction, Zauzmer points out that the book only covers up to the March, 2018 ceremony. It obviously can’t make predictions about future Oscars, though it might suggest some tactics you could use for making your own if so inclined. Zauzmer has been successful enough in the film arena that he writes for The Hollywood Reporter and other more general outlets. You can track down his work, including pieces on this years Oscar nominees, here.

Posted in Animation, Animation: Pixar, Awards, Hollywood: The business |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Oscars by the numbers open printable version

| Comments Off on Oscars by the numbers

|