Sunday | September 29, 2019

DB and KT, front row center, at the screening of The Lighthouse. Photo by Shelly “Sales Agent Cinema” Kraicer.

DB here:

Storytelling cinema depends on characters, and our relations to them. At the level of individual scenes, we can be more or less restricted to what they experience; we can know as much as they do, or more, or less. Across a film, the filmmaker can attach us consistently to one or two characters, or instead roam freely among many viewpoints. And within a scene, the filmmaker’s choice of camera placement can put us “with” one character or another.

In other words, narrative cinema 101. But it’s worth remembering that these are forced choices. As a filmmaker, you can have restricted or unrestricted access to characters, but at every moment you have to choose one or the other. How objective or subjective will you make your presentation? Will you limit your camera setups or go for ubiquity–that tendency to give us shots divorced from the immediate situation? Examples are a drone-delivered image above a city, or that sudden high or low angle that calls our attention to a detail the characters may have missed.

Three films at the Vancouver Film Festival presented a nice menu of attachment options–ways in which we can be tied to our protagonist. All are well worth your attention, so without getting too much into spoilers, I’ll use them as an occasion to study how these forced choices are handled creatively.

The party’s over

Take as a midrange example The Realm (El Reino, 2018), a Spanish political thriller directed by Rodrigo Sorogoyen. Manuel López Vidal is a brisk, no-nonsense functionary enjoying the good life thanks to the corruption of his party. He and his colleagues, the Amadeus Group, meet regularly over expensive meals to plan their schemes of influence-peddling and money laundering. They tease their fastidious accountant about his meticulous ledgers, but those records will become important to Manuel when one colleague leaks incriminating audio tapes of Manuel’s dealmaking. There’s an orgy of document shredding, damage control among the party’s top brass, and the growing likelihood that Manuel will go to jail.

The screenplay restricts nearly all the action to Manuel. This method is established at the start, when a long tracking shot follows him from the beach as he strides into an Amadeus lunch. Thereafter, we’re with him as he learns of the danger he’s in and mounts one tactic after another to save himself. At a couple of moments the camera lingers on his colleagues’ reactions after he’s left the scene, but on the whole we’re firmly attached to him. Some virtuoso long takes, including a ten-minute shot that follows Manuel’s frantic search for the ledgers, virtually fetishize our adhesion to the protagonist.

By and large, the presentation doesn’t delve into his mind. The throbbing techno score conveys his growing panic as he strides from one confrontation to another, but we get no voice-overs, or flashbacks, or mental imagery. And we don’t see Manuel confide his plans to others (although he seems to have told his wife some of them offscreen). This degree of objectivity allows more suspense, as his schemes to save himself unfold in the moment. We must figure out why he’s bracing one colleague, or bursting into a friend’s home in the course of a teenage party. His manic resourcefulness is all the more impressive when he keeps dodging new problems, often revising his plan on the fly.

It’s no easy feat to maintain tension across two hours, especially when we’re asked to invest our sympathy in a corrupt politician, but The Realm manages it. It’s achieved partly through the trim, crisp performance of Antonio de la Torre but also through plot and style: the refusal of omniscient narration (say, showing us the police or party officials tracking him) and a mild degree of camera ubiquity that accentuates the character’s plight, whether in a meeting or all alone.

The Realm is a good example of how manipulating character attachment can strongly engage the audience. We know just enough to understand Manuel’s crisis, but without access to his mind, each scene can yield a surprise when he comes up with a new survival stratagem.

A lot from a little

I hadn’t really considered the Dardennes brothers “minimalist” filmmakers, but seeing Young Ahmed brought home to me how strictly they’ve limited their cinematic palette. Given their emphasis on actors and faces, you might think they rely on the sort of “intensified continuity” on display in modern film and television. Yet they’re far more purist than that, and they take objective presentation further than does Sorogoyen.

They seldom use long shots, let alone establishing shots: a scene starts in medias res with character action, shot from quite close. Filming in handheld long takes, they avoid shot/reverse-shot cutting, either panning between participants in a dialogue or simply framing them in tight two-shots.

The Dardennes minimize camera ubiquity. Not for them the picturesque, distant shots that The Realm sometimes provides. In a car carrying two passengers, the camera isn’t lashed to the hood or filming alongside; it’s in the back seat.

True, cutting yields some ubiquity. When Ahmed’s teacher pursues him through a classroom, she runs ahead of us but then, in the next shot, she catches up with him as he’s about to leave the building.

Like most cuts, it’s an instantaneous change of position that a real observer couldn’t execute. Still, this frame-edge cut creates simple continuity, driven by dramatic necessity and barely noticeable. The cut is softened by a staging that neatly settles into a standard over-the-shoulder setup.

Apparently uninterested in pictorial composition, these filmmakers simply center their subjects in undistinguished framings. No shot becomes strikingly lit or framed. There’s no nondiegetic music, and the soundtrack is subdued; of all modern filmmakers, they benefit least from surround channels.

As in The Realm, the Dardennes’ minimalist approach works well in tying us to the protagonist, while also denying us direct access to his mind. Ahmed, an adolescent in Liège, has given up video games for fundamentalist Islam. Convinced by his imam that his classroom teacher has become an apostate, he decides to take action against her.

His plans emerge wholly through his actions. Without benefits of voice-over, subjective sequences, or flashbacks, we must infer how he will respond to the demands of the Qu’ran as he has been taught to understand it.

The Dardennes’ objectivity doesn’t make the plot hard to follow. A dozen minutes into the film, the premises are clear, the main characters (Ahmed’s mother, his imam, his teacher) are delineated, and Ahmed’s motivation is established. At the half-hour point, his mission is launched. Apart from the ellipsis I mentioned, everything that follows stems from the dramatic premises. And however horrifying Amed’s plans may be, the wistful, pursed-mouth young actor Idir Ben Addi is mesmerically angelic. His glasses make him look adorable.

The style also keeps everything clear. The texture is close to that of documentary filmmaking, but of course the Dardennes’ films are scripted and staged. There’s a high degree of artifice in their apparently artless method. As in the more flamboyant Birdman, their long takes catch every reaction and gesture with great precision.

We always see what we need to see at just the right moment. When something is suppressed–here, the result of a violent knife attack–it’s not an accident (as if the camera were in the wrong spot) but rather the result of our attachment to Ahmed and a clever narrative ellipsis. We could have had a cut like the one in the school, but we remain with Ahmed, and in fact know a bit less than he does about the result of the violence.

All of which is not to deny the originality of Young Ahmed. All the Dardennes films seem modest, but they are, within their limits, quite ambitious in using dramatic psychology to probe social problems. Throughout, I think, we are asked to reflect on how firmly Ahmed believes in his version of Islam. Is it a transitory teen obsession or is he on his way to becoming a dogmatic martyr? We watch his behavior, his encounters with farm life and a young girl, for any signs that his lonely, taciturn demeanor will crack. In other words, this is a suspense film–one based less on the threat of violence (which is there, to be sure) than on how a boy who hasn’t fully formed his character will define himself.

Not such light housekeeping

Both The Realm and Young Ahmed are, to varying degrees, objective in their presentation. We must judge characters by what they do and say. Something very different is going on in Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse. It too adheres largely to one character, but a battery of cinematic techniques, including camera ubiquity, works to plunge us into the man’s mind.

Although the film is a two-hander, it doesn’t balance viewpoints. Thomas Wake, an experienced lighthouse supervisor, arrives at his post with the novice Ephraim Winslow. Almost immediately we are attached to Winslow, who’s assigned grimy menial duties while Wake tends the beacon. Wake tells Winslow that his previous assistant went mad from the weeks of isolation, and very quickly Winslow struggles against the bleak, craggy island they’re on.

We’re prepared for an assault on your senses by the opening, when a ship roars out of the fog toward us. Thereafter, Wake subjects Winslow to a punishing routine of cleaning the cistern, heaving coal into the boiler, and scrubbing floors, while nightly meals with the nattering old salt are just as hard to bear. Winslow’s misery is rendered in vivid, expressionist terms. The deafening fog horns, thunderclaps, and boiler blasts are reinforced by stark, ominous black-and-white imagery. (The film was shot on 35mm film.) Winslow seems trapped in a world of raging elements and gigantic machines.

Eggers builds our affinity with Winslow through classic techniques. He watches Wake at the beacon from a distance; we get optical point-of-view shots of discoveries (real? imagined?) that start to unhinge him.

All the drudgery and pain, punctuated by Wake’s continual harangues and farts, lead Winslow into fantasies and hallucinations. His deterioration is rendered in shock cuts and distended compositions reminiscent of Welles’ Mr. Arkadin or German’s Hard to Be a God. Some will compare the film’s over-the-top climax to that of Aronofsky’s Mother!, but The Lighthouse, with its rapid montage and Gothic chiaroscuro, harks back to silent cinema. The fact that it’s shot in the 1:1.17 ratio favored by early sound film gives it an archaic feel as well. The dialogue, a late title informs us, is drawn from nineteenth-century sources, including Melville and Sarah Orne Jewett.

The Lighthouse has a cadence typical of modern horror films, but Kristin points out that it’s an expressionistic Kammerspiel too–a subjectively tinted drama setting very few characters in a constrained locale. Eggers shows that you can renew a genre’s appeals by reviving imagery from a classic period of film history. When you do it, you’ll still have to make fundamental choices about viewpoint and camera placement. They come with the territory.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis and Shelly Kraicer for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on classic Kammerspiel films go here and here.

The Lighthouse (2019).

Posted in Directors: Dardennes, Festivals: Vancouver, Film comments, Narrative strategies, National cinemas: Spain and Portugal |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Attachment anxieties at the Vancouver International Film Festival open printable version

| Comments Off on Attachment anxieties at the Vancouver International Film Festival

Sunday | September 22, 2019

DB here:

Another bountiful disc release from Criterion: Ozu’s 1952 classic in a 4K digital restoration, with newly translated subtitles. It comes with an enlightening essay by Junji Yoshida and Daniel Raim’s ingratiating documentary on Ozu’s collaboration with his screenwriter Kogo Noda. I contributed a video essay on the film. The most wonderful bonus is Ozu’s 1937 feature What Did the Lady Forget?, which has fascinating affinities with the later movie.

What did which lady forget?

I’ve long been a fan of What Did the Lady Forget? It’s a quasi-screwball comedy treating the clash of the sexes and the generations. As is typical for Ozu, it starts light, abetted by a languid guitar-and-banjo soundtrack, before sidling into graver moments.

In my commentary I touch on its social satire. As the Shochiku studio began making more films about prosperous families, Ozu moved away from the working-class and salaryman milieus he had explored in many masterpieces of the 1930s. I argue in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema that this film’s comic treatment of the professional class looks forward to what he’ll offer in Equinox Flower (1958) and other postwar films.

A married couple hosts a visit from their sashaying, cigarette-smoking niece, a moga (modern girl) who turns out to be not quite as tough as she thinks. While exploring the city’s nightlife (and occasionally brandishing a fencing foil), Setsuko exposes the tensions in the apparently easygoing marriage. The comedy drifts into moments of Ozuian pathos and melancholy–a chastened Setsuko has to leave Tokyo–but the film ends on a light note.

Stylistic finesse is on display throughout. The framings are dazzlingly inventive, the perspectives are steep, and we’re given those quietly permutational “establishing shots” that introduce scenes in Setsuko’s room.

The weird graphic matches in the two boys’ “hit the spot” game could not have been devised by anybody else.

I just love this stuff. There’s so much here, how can this movie be only 70 minutes long?

What Did the Lady Forget? contains a disturbing burst of domestic violence. But the husband soon regrets it, and Ozu and his screenwriter Akira Fushimi develop the crisis in way that keeps shifting our judgment about what characters learn from the incident.

A distressed marriage

In a parallel situation in the “remake,” The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, the husband remains calm in the face of his wife’s criticism. Mokichi is far from a paragon (he’s a phlegmatic workaholic, he’s out of touch with young folks and urban culture), but at home he’s quiet and apologetic. When Taeko complains about his table manners, he tries gently to explain why he slurps his rice.

Daniel Raim’s short on the Ozu-Noda collaboration concentrates on the planning of An Autumn Afternoon (1962), well-documented in Donald Richie’s Ozu. But we also have some records of their work routine on Green Tea. Ozu kept no fewer than five notebooks that year, sometimes recording the same event in two or more.

On 20 January, he notes that he and Noda are “bringing back a problematic script.” That’s because the original Flavor of Green Tea over Rice was refused by censors in 1940. In early 1952 Ozu was in the process of moving to Kamakura, so the two men’s collaboration took place in inns, Noda’s home, and the studio. One notebook logs Ozu’s production schedule, while others are more personal.

Ozu’s films from the 1950s on were typically planned in the winter, shot in spring and summer, and premiered in the fall, as if he were determined to document each year’s good weather. Ozu and Noda began writing Green Tea on 29 February and finished on 1 April, sometimes preparing three scenes a day. After consulting with Shiro Kido, the studio head, they revised the script. Ozu’s efficiency in planning every scene and sketching every shot allowed production to proceed fast. The crew began shooting on 7 June, in an office set. They finished on 13 July (“Finally, rest!”) and The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice premiered on 1 October.

Pretty intensive work. But you wouldn’t know it from the companion notebooks. Among chronicles of naps, baths, social gatherings, changing weather, baseball games, and bar-hopping with friends, how did they get any work done? Above all there’s Ozu’s careful record of his alcohol intake (“drank until 2 AM”). A stomach ache makes him think he might have an ulcer. “I must resolve not to drink too much. And stick to it!” Today we would call him a high-functioning alcoholic. “With the whisky I drank this morning and the shumai I brought back from Tokoen, I wasn’t at all hungry tonight.”

As in his films, the everyday and the unusual get equal treatment. While staying at one inn, he calmly observes the arrival of a woman’s baseball team. And he remained a cinephile. He’s happy to interrupt an evening of dining and drinking to go see William Dieterle’s September Affair (1950).

The film that resulted, I suggest in the supplement, modulates between satire and a generous comedy that gives the main characters, no matter their failings, moments of warmth and dignity. With a light hand Ozu summons up narrative parallels, and he spotlights the split between men’s culture and women’s culture. A troubled marriage is given due weight, but it’s saved by graciousness, as when (above) Mokichi rescues Taeko’s sleeve from the water in the sink.

Ozu carries the humor down to the fine grain of technique, teaching us to play a private cinematic game in which the characters participate all unawares. The Criterion creative team has ingeniously used split screens to help me show the evolution of stylistic patterns across the film. Shedding my Mr. Rogers sweater for a sport coat, I try to crack the mystery of those eerie tracking shots. Like the situations and the dialogue, these barely moving images ought to make you smile.

Thanks to producer Elizabeth Pauker and her colleagues at Criterion, especially Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson. Thanks as well to Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison.

Ozu’s diaries of shooting The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice are available, with helpful annotations, in Yasujiro Ozu: Carnets 1933-1963, trans. Josiane Pinon-Kawataké (Editions ALIVE, 1996), 267-318.

My book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is available for free here. Color pictures and everything! But be patient; it’s big and takes a while to download. There are many entries on Ozu and Donald Richie elsewhere on this site.

What Did the Lady Forget? (1937).

Posted in Directors: Ozu Yasujiro, Film technique, National cinemas: Japan |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Ozu the compassionate satirist: THE FLAVOR OF GREEN TEA OVER RICE on Criterion Blu-ray open printable version

| Comments Off on Ozu the compassionate satirist: THE FLAVOR OF GREEN TEA OVER RICE on Criterion Blu-ray

Monday | September 16, 2019

Waiting for the Barbarians (2019).

Kristin here:

The 76th Venice International Film Festival is over, but I have two films yet to blog about. This will be our final entry. Soon we’re both off to the other VIFF, the Vancouver International Film Festival, from which we will of course be blogging.

Waiting for the Barbarians

I was particularly looking forward to this film, since I admire Ciro Guerra’s two previous features, Embrace of the Serpent (2015) and Birds of Passage (2018). It was rather surprising that Guerra should have a new film premiering only a year after Birds of Passage, especially since both are in their own ways epics in relation to most other art films. The fact that it stars the great stage and screen actor Mark Rylance was another factor in its favor.

Oddly enough, the morning press screenings and evening red-carpet screening of Waiting for the Barbarians were relegated to the penultimate day of the festival, Friday, September 6. It was the last of the films in competition to be shown, with The Burnt Orange Heresy (in the festival’s Fuori Concorso thread) the closing film on Saturday. By that point, quite a few of the foreign-press members had departed for Toronto or elsewhere. The Friday afternoon press conference, despite including Johnny Depp on the panel (above), was SRO, but there was no immense queue to get and and very few standing at the sides or sitting on the central stairs, as usually happens when big stars are present.

Overall the film has received lukewarm reviews, with a few more praising pieces mixed in. Both David and I, however, found it riveting. It deals with the unnamed Magistrate (Rylance), who rules a fort community on the border of a desert landscape inhabited by nomadic tribes. The Magistrate controls the place with a loose rein, meting out mild punishments for what he perceives as minor infractions by the local population. He seems content, excavating for ancient wooden rods inscribed with undeciphered texts and apparently has a relationship with a sympathetic local prostitute. He seems friendly with the people under his care and has taken the trouble to learn their language.

The countries which this border area separate are never identified and are clearly fictional places serving to portray the horrors of colonial domination by western nations. Clearly the white officials and soldiers in the film are not intended to be British. The flags on display bear no resemblance to the Union Jack and the costumes are not British. The local nomads speak Mongolian, and the main female character, referred to only as “the Girl,” is played by Gana Bayarsaiknan, a Mongolian performer.

The conflict is set moving by the arrival of Colonel Joll, an ominous figure in black, sporting bizarre dark glasses with frames of twisted wire (in the background of the frame at the top). His suggestion that he will use “pressure” to force the locals to confess their crimes turns out to be a considerable understatement. Joll ventures a little way into the the territory of those he calls “the barbarians.” He claims to turn up evidence that the local people are plotting to attack the colonial forces along the border. He has discovered this evidence though torture.

Much more description would provide too many spoilers. In general, the Magistrate tries to reason Joll and his confederates out of their plans. He also frees prisoners and nurses the native girl, who has also been tortured, back to a semblance of health. Eventually he finds himself driven to rebellion.

The film, with exteriors shot in Morocco, creates a vivid sense of a fortress community isolated from the world, and the cinematography as the Magistrate leads a small group to try and return the Girl to her people is austerely beautiful.

So far all the release dates for Waiting for the Barbarians are for festivals, including the London Film Festival. Whether it will be released in the US, as Guerra’s two previous films were, is unknown. I would suggest giving it a chance, despite some lackluster reviews. It’s another film that would lose much of its effect when streamed on a small screen.

Adults in the Room

Each year a small number of celebrities receive special awards, essentially salutes to long and fruitful careers. This year the main honors went to Pedro Almodóvar, Julie Andrews, and Costa-Gavras. We didn’t catch the awards ceremonies themselves, and the Amodóvar and Andrews ceremonies were followed by classic films of their past (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Victor Victoria respectively). Costa-Gavras’ career started as an assistant director to René Clair, René Clément, Henri Verneuil, Jacques Demy, Marcel Ophüls, Jean Giono, and Jean Becker before beginning to direct on his own. Apart from his numerous features, perhaps most notably Z (1969), he has been president of the Cinémathèque Française since 2007.

Now, at age 86, he brought with him a new feature, Adults in the Room, a dramatization of the tensions and strategies of the politicians and diplomats struggling to find a solution to the Greek financial crisis.

As in most such films, the actors have been chosen for their resemblance to the historical figures. In the upper of the two images below, for example, Josiane Pinson plays Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, and Daan Schuurmans is Jeroen Dijsselbloemm, president of the Eurogroup.

The film begins with the unlikely election of a leftist government in Greece (the Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza) in January of 2015. The film sticks largely to the point of view of Yanis Varaufakis, the fiercely dogged Finance Minister. His memoirs of the struggle to refinance Greece’s overwhelming debt and to keep Greece from being expelled from the European Union were the basis for the script by Costa-Gavras.

Remarkably, Costa-Gavras follows the events through an almost unbroken series of conversation scenes. These center on clashes between Varaufakis and Greece’s Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, and on stormy meetings involving representatives of the Eurogroup and the infamous “Troika” (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund). The Troika faction, which had bailed out the Greeks and insisted on disastrous austerity measures, absolutely refuses Greece’s demand that the loans stop and that the debt be devalued to a viable level.

This does not begin to convey the complexity of the Greek crisis, but Costa-Gavras manages to create suspense, whether or not we can actually follow exactly what is going on. There are moments when Varaufakis’ negotiation strategies are withheld from us, and we are as puzzled as the officials watching them from across the room, as in this glance-POV cut:

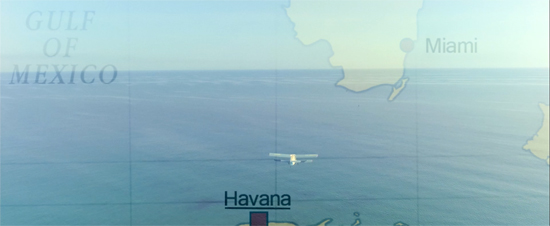

These meetings are linked primarily by shots establishing the various cities in which these complex and fruitless meetings take place. Often superimposed titles reveal the locations, as when the Greek Prime Minister arrives in Brussels for one such meeting (see bottom).

By the end we are not left with a thorough grasp of the intricacies of these events, which would hardly be possible for a crisis that started around 2009 and is still going on. Still, we gain a somewhat better understanding than we are likely to have on the basis of news stories stretched sporadically over over so many years. We are also left indignant at the determination of the Troika to persist in the very policies that drove Greece deeper and deeper into debt. Some have found the film tedious in its intense focus on meetings and strategies. Others I talked to after the press screenings found it fascinating. Certainly the film and its source book have chosen the brief period of the crisis (about six months) that shows most clearly and dramatically what Greece faced from the rest of the EU and why its crisis still has not ended.

For one final time this year, thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Adults in the Room (2019).

Posted in Festivals: Venice, National cinemas: Greece, National cinemas: Italy |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2019: Political dramas, allegorical and real-life open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2019: Political dramas, allegorical and real-life

Wednesday | September 11, 2019

The Laundromat (2019).

DB here:

Every now and then I wonder whether network narratives, to revert to the term I coined a while back, have faded from the scene. Although there are some examples earlier in film history, that storytelling model had a sustained burst after Altman popularized it in Nashville (1975). Other filmmakers took it up, especially in the 1990s (Before the Rain, Exotica, Go, Pulp Fiction, etc.) and the 2000s (Babel, Dog Days, Love Actually). I don’t seem to see so many nowadays, and the almost universal loathing greeting Life Itself (2018) might seem to indicate that a tale relying on remote connections and unexpected convergences had run its course.

Surprising, then, to see three items at Venice that rely to a degree on the network narrative format. Each is based on a nonfiction book aiming to reveal the dynamics of a large-scale process. In each film, process becomes a framework for personal stories and converging fates.

Wasps in the Caribbean

Olivier Assayas’s Wasp Network isn’t as far-reaching as the title implies. It concentrates on two couples and one individual caught up in 1990s spying. When René Gonzales, a pilot, defects to Florida, he seems to be seeking freedom and a new life working with Cuban exiles to destabilize Castro’s regime. Branded a traitor, he leaves behind a wife and daughter who must bear social opprobrium. Actually, he is a Cuban agent, part of the “Wasp Network” that will infiltrate the anti-Castro forces.

Another exile, Juan Pablo Roque, works with the Network, but he is also leading a double life–one quite different from René’s. Just as René’s sacrifice wrecks his relation with his family, the headstrong Juan Pablo jeopardizes his relation to his lover Ana Margarita. Both men are linked to Gerardo Hernandez, who coordinates the Network.

As in most spy stories, we’re led to discover double agents and surprise alliances, as well as the conventional emphasis on the personal cost of espionage. As the film goes along, that emphasis becomes stronger; scenes tracing the tactics of the anti-Castro forces (such as invading Cuban airspace to drop leaflets) give way to long confrontations between couples and the efforts of Rene’s wife Olga to unite with him in the US.

Because network plots need to fan out across many characters, filmmakers often break up the linearity of time. In Wasp Network, the reunion of the two major defectors, Juan Pablo and René, is followed by a passionate scene of Olga being defeated by Cuban bureaucracy. Abruptly the plot skips back four years to introduce Gerardo, and his career as a double agent is summarized. A montage, complete with a narrator’s voice-over, links the three men in the years 1990-1992. Then, back in the present, Gerardo meets with Olga to reveal that René is a patriot, not a traitor.

Visually, the film is surprisingly ordinary, I thought, sort of standard TV. If you like over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot, there’s plenty here for you.

Assayas garnishes his reverse angles with alternating push-ins, a technique that has become a bit hackneyed since John McTiernan’s skillful use of it.

The film compels some interest by virtue of its origins. Based on the FBI case against the “Cuban Five” and the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, it employs vintage broadcast news coverage cut in for expository purposes. I had known almost nothing of this historical episode, and thanks to the cooperation of Cuban authorities Assayas benefits from showing a story we Americans seldom see. Still, by concentrating on only a few characters and having them played by Édgar Ramírez, Penélope Cruz, and Gael García Bernal, whose presence demands extensive scenes, the larger dynamic of the Wasp Network fades into the background. Despite its title, maybe it’s only a borderline case of a network narrative.

Coke ZeroZeroZero

ZeroZeroZero is also based on journalistic reportage, in this case Roberto Saviano’s book of the same title. (An earlier Saviano true-crime investigation is the source of the 2008 film Gomorrah, another network narrative.) The subtitle of his book–Look at Cocaine and All You See Is Powder. Look Through Cocaine and You See the World–suggests the vast ambition of his project. From the book Sky, CanalPlus, and Amazon Prime have developed an eight-part series to be broadcast and streamed in 2020.

Since I’m not the world’s biggest TV consumer, I wasn’t interested until I read the presskit, which promises something sweeping.

The series follows the journey of a cocaine shipment from the moment a powerful cartel of Italian criminals decides to buy it until the cargo is delivered and paid for. Through its characters’ stories, the series explains the mechanisms by which the illegal economy becomes part of the legal economy and how both are linked to a ruthless logic of power and control affecting people’s lives and relationships.

The prospect of following a coke-packed container as it passes through various hands appealed to me. I enjoy circulating-object plots like Winchester 73 and The Red Violin, as well as those 1920s Soviet Constructivist “biographies of things” (such as Ilya Ehrenberg’s Life of the Automobile).

ZeroZeroZero, though, isn’t quite that sort of thing. Judging by the first and second episodes, the only ones screened at Venice, this will be more conventional. The plot shifts among dramas within groups of stakeholders in the shipment. We see the power struggle in an Italian crime family, with a son aiming to usurp his grandfather. There’s another family drama in New Orleans, where a ruthless shipping-company owner insists, against his son’s and daughter’s resistance, on booking the cargo. In Mexico, a corrupt special forces sergeant works behind the scenes to assure that the shipment will not be disturbed.

The narration cuts among these storylines until, at the end of episode 2, the cargo embarks on the seas. Doubtless the remaining episodes will ramify into other story lines, but I’d expect at least the Italian and American ones to be on tap throughout–if only to maintain the interest of streamers’ European and US audiences.

The film was directed and co-written by Stefano Sollima, who has done several TV dramas as well as the feature film Sicario–Day of the Soldado. ZeroZeroZero certainly had a higher-gloss look than Wasp Network, with dramatic lighting and elaborate action scenes. One of these, a police attack on the big meeting of the stakeholders, is replayed from different character viewpoints in the two episodes. Like Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero amplifies its expanding network through time-shifting, and this attack is revealed to be a node, a point of convergence among the three main groups of characters. Given current TV’s fascination with scrambled time schemes, I’d expect other nodes and replays to emerge in the course of the series.

Capitals of capital

Eisenstein planned to make a film of Marx’s Capital. He would have used his montage editing methods to survey an economic system–without benefit of individualized protagonists. In The Laundromat Stephen Soderbergh has tried to do something akin to this, but like most filmmakers he’s obliged to personalize his drama (as he did in Traffic and Contagion). Soderbergh has compared the film to Dr. Strangelove, largely because of the need to make a devastating situation entertaining. But I think his film recalls Strangelove as well in its emphasis on villains who get caught up in the insanely complicated system they create.

Mossack Fonseca was a law firm in Panama that specialized in tax evasion. It registered over 300,000 companies, many of which were shell entities that enabled money laundering and fraud. The firm had subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Hong Kong, Switzerland, and other countries. In 2016, German investigative journalists published 11.5 million internal documents known as the Panama Papers, mostly centering on Mossack Fonseca. As the journalists explain:

Clients can buy an anonymous company for as little as USD 1,000. However, at this price it is just an empty shell. For an extra fee, Mossack Fonseca provides a sham director and, if desired, conceals the company’s true shareholder. The result is an offshore company whose true purpose and ownership structure is indecipherable from the outside.

Despite its vast scale, the firm represented at most ten percent of the global market of offshore finagling.

Tax havens and shell companies are more or less legal. What brought down the company was the breach of confidentiality. In addition, the possibility of fraud hovered over the big names revealed as beneficiaries. Politicians throughout Europe and China were named, as were filmmakers Jackie Chan and Pedro Almodóvar. International villains associated with Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin moved money through Mossack Fonseca; a Russian cellist had holdings of $2 billion. After the leaks, the rich couldn’t trust Mossack Fonseca to keep their secrets.

Building on Jake Bernstein’s book Secrecy World, Soderbergh and screenwriter Scott Z. Burns have concocted a sweeping tale of how the rich are very, very, very different from you and me. But in scale, the network they’re surveying dwarfs the Wasps and the voyage of a coke shipment. How do you convey the vastness of an alternative financial system?

The film’s pop-Brechtian mode of presentation will earn comparisons to The Big Short, but here instead of one-off celebrity tutors (Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain) we get the chattering rogues themselves, Jürgen Mossack (Gary Oldman) and Ramón Fonseca (Antonio Banderas). Their to-camera accounts of “fairy tales that actually happened” settle into a block construction, five chapters “based on actual secrets.”

The first chapter title, “The Meek Are Screwed,” provides an emblematic case of how the little people are connected with this network of virtual money. Chief among those Meek is Ellen Martin (Meryl Streep), whose husband Joe is drowned when a tour boat capsizes.

Hoping to have her grief assuaged by an insurance settlement, she learns that one isn’t forthcoming because the boat company bought a worthless policy from a shell company. The film’s first two chapters follow her efforts to find someone responsible. She finally tracks down a fraudster named Boncamper, a Mossack Fonseca figurehead who has grown rich (and accumulated two families) simply by signing thousands of documents.

Having shown how the shell-company shuffle affects ordinary folks, the film moves on to the high and mighty. One chapter traces the backstory of the company, another shows how an extraordinarily rich family uses the system to one-up each other, and a final chapter depicts murder among the Chinese plutocracy. The fourth block, illustrating the lesson of “Bribery 101,” is especially juicy in showing a father using bearer bonds to force his daughter to keep silent about his extramarital affair. As Marx and Eisenstein would expect, economic relations seep into personal ones. Bribery is all in the family.

The Laundromat’s breezy, self-righteous impresarios cast a comic tone over everything. Even the murder doesn’t seem awful, considering the victim’s own corruption. Only at the end does indignation emerge in a twist. Ellen, almost forgotten for the last half-hour, reappears in a new guise and takes over the narration from the villains. An agitprop ending reminds us that the capital of money laundering may well be the US, where Nevada, Wyoming, and above all Delaware play a role comparable to the Caribbean. Soderbergh and Burns (who confess to having offshore stashes themselves) end by firmly snagging their American audience in the colossal spiderwebs of global capital.

Nearly every narrative involves a social network of some size, even if it’s only a family. The most thoroughgoing network plots provide us roughly equal attachments to many viewpoints. The film demotes individual protagonists, in favor of revealing x degrees of separation among several individuals. Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero, and The Laundromat don’t have the complexity of the network narratives of earlier years, but they serve to remind us that the network schema can be tweaked to suit the needs of particular creative projects.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

For more on network narratives, see Chapter 7, “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema. Jeff Smith considers Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood as a network narrative, and earlier entries (such as here and here) develop the idea as well.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

ZeroZeroZero (2020).

Posted in Directors: Soderbergh, Festivals: Venice, Film comments, Narrative strategies, National cinemas: France |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Telling the big story: Network narratives at Venice 2019 open printable version

| Comments Off on Telling the big story: Network narratives at Venice 2019

|