Sunday | August 25, 2019

The Wrecking Crew (1969).

Jeff Smith’s blog entry on Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood has been our most popular offering this year. In the wake of that, he offers a few more observations. (DB)

The film’s commercial success confirms the value of original intellectual property, up to a point. Four weeks after its release, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood’s current box office total is just over a $120 million for the domestic market. It’s also earned about $117 million in foreign markets. It seems likely to be the only film this summer to surpass $200 million globally that is neither a remake, a sequel, nor a franchise film.

Still, I agree with the general sentiment that there are no blue-sky lessons to be learned here. Tarantino is one of those rare talents who offers viewers a unique personal vision that has appeal beyond the arthouse. (Others would include Alfonso Cuarón, Damien Chazelle, and, of course, Christopher Nolan.) Current projections put Once Upon a Time . . .’s cumulative box office total around $385 million. That figure would fall short of Django Unchained’s $425 million, but would be considerably better than Inglourious Basterds’ $321 million. Not quite Inception or Gravity money, but not chump change either.

Tarantino’s film also gives Sony Pictures something to promote this Oscar season, along with Tom Hanks as Fred Rogers in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood and Greta Gerwig’s take on Little Women. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood seems likely to snag several nominations in major categories. I would be very surprised if it didn’t score nods for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress, and Best Cinematography.

I also have a few stray observations that didn’t make it into my earlier post. One is another element of counterfactual history.

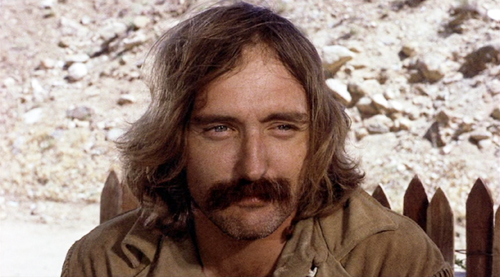

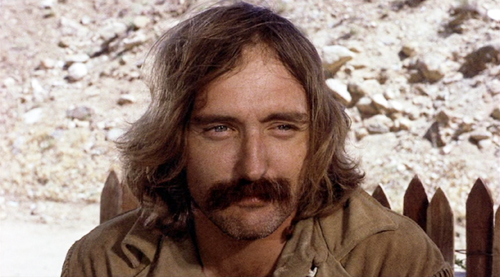

One evening Cliff and Rick watch “All the Streets Are Silent,” the episode of The F.B.I. that Tarantino has recreated. They want to see the Rick’s guest spot as Michael Murtaugh, alongside James Farentino and Norman Fell. But who actually played Murtaugh in that episode? None other than the late, great Burt Reynolds, whom Tarantino had originally cast in the role of George Spahn.

Reynolds is among a trio of sixties stars who served as role models for Rick Dalton. Steve McQueen is perhaps the most notable, both as a character who appears in the scene at the Playboy Mansion and as the star of The Great Escape, a part Rick had hoped to get. McQueen also came to movies from the small screen. From 1958 to 1961, he was the star of Wanted: Dead or Alive, a show that was an inspiration for Bounty Law.

The second model for Rick is, of course, Clint Eastwood. Eastwood made his mark as the star of TV’s Rawhide before achieving international fame in spaghetti westerns playing Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name. This trajectory is echoed in Rick’s late-career arc, although his westerns don’t achieve the renown of Eastwood’s.

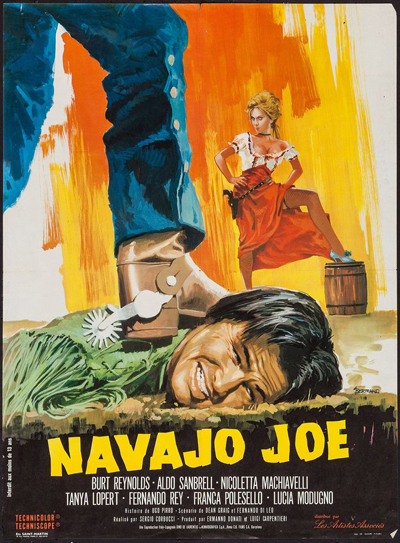

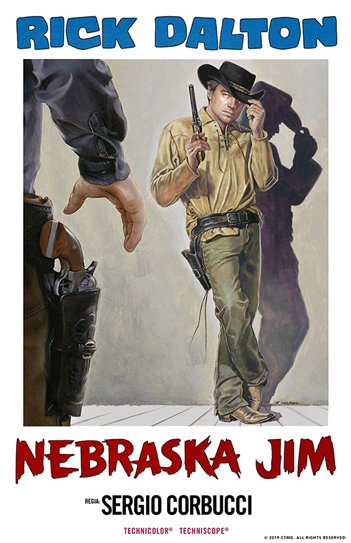

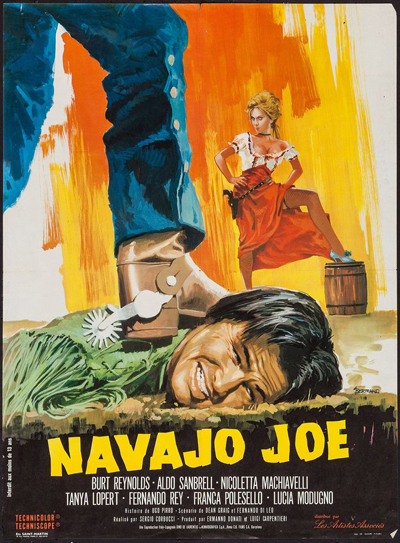

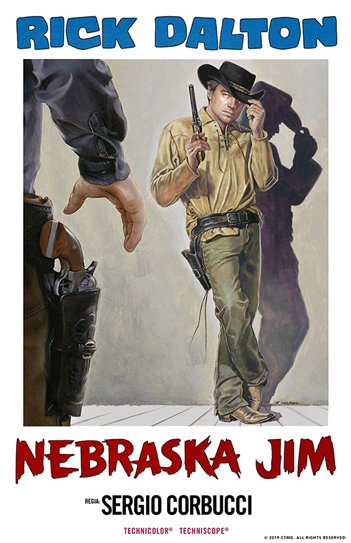

Burt Reynolds’ path to stardom was somewhat different from McQueen’s and Eastwood’s. Reynolds played only a supporting role on CBS’s Gunsmoke from 1962 to 1965 before he went to Italy to star in Sergio Corbucci’s Navajo Joe. Again, Rick follows this pattern, as we see when he moves from supporting TV parts to starring in the fictional Corbucci title Tarantino devised, Nebraska Jim.

What most differentiates Reynolds from the other two stars, however, was his close relationship with stuntman Hal Needham. Needham did stunt work in more than 300 films and 4500 television episodes, often acting as Reynolds’ stunt double. He also did uncredited stunt work on a handful of films and shows referenced in Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, such as Mannix, C.C. & Company, and The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean. Needham would later direct Reynolds in several box office smashes, like Smokey and the Bandit and The Cannonball Run. In Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, Rick’s rapport with Cliff was inspired by Reynolds’ and Needham’s long friendship, a professional association which spanned almost forty years.

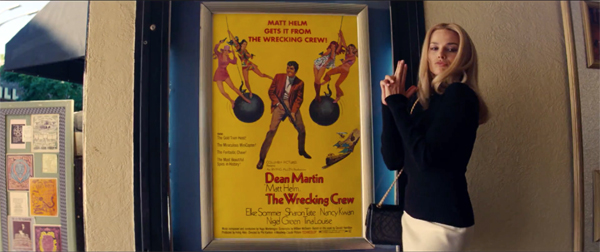

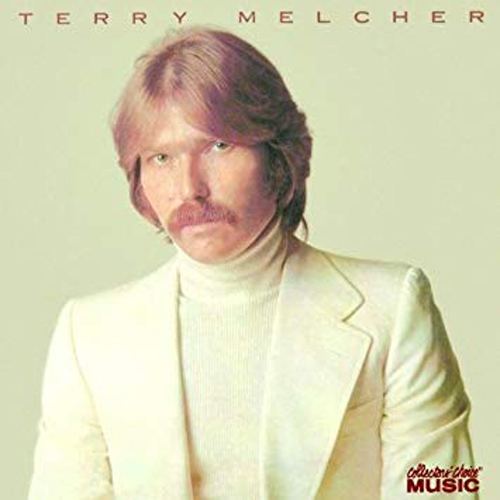

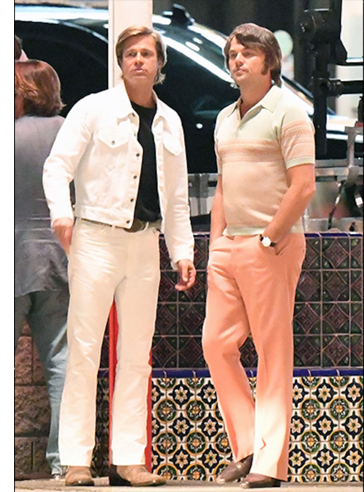

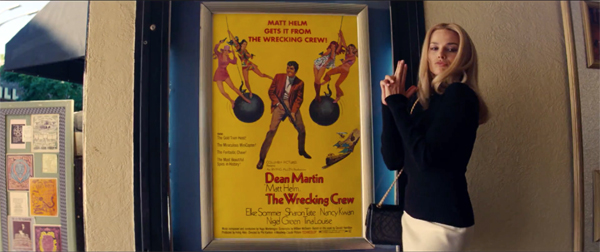

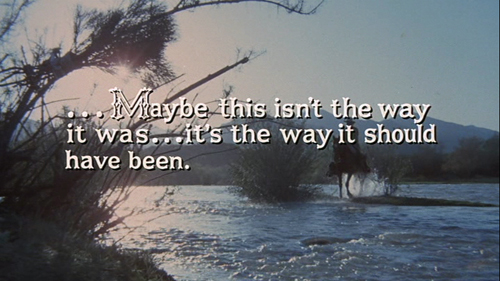

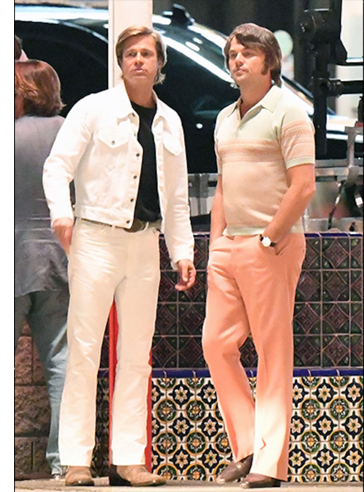

Lastly, a sharp-eyed reader of the blog, Karl Wallin, also pointed out another connection between Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood and The Wrecking Crew. (Karl is an old chum and the only person I know even more obsessed with Tarantino’s film than I am.) Karl noted that the white denim suit that Cliff wears in the blood-soaked climax matches the white suit Matt Helm wears during the last twenty minutes of The Wrecking Crew. (See top still.) Lastly, a sharp-eyed reader of the blog, Karl Wallin, also pointed out another connection between Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood and The Wrecking Crew. (Karl is an old chum and the only person I know even more obsessed with Tarantino’s film than I am.) Karl noted that the white denim suit that Cliff wears in the blood-soaked climax matches the white suit Matt Helm wears during the last twenty minutes of The Wrecking Crew. (See top still.)

Karl pointed out another serendipitous connection between different aspects of the Manson case. As I mentioned in the earlier post, Manson met a couple of times with record producer Terry Melcher about the prospect of signing a contract. Melcher ultimately soured on the deal, which led Manson to target the producer’s former residence as the site of the first murders. On some of the albums Melcher produced, he worked with a loose collection of extremely talented session musicians that were the Los Angeles equivalent of Motown’s The Funk Brothers. The group included several notable instrumentalists, such as guitarists Glen Campbell and Tommy Tedesco, pianists Leon Russell and Dr. John, bassist Carol Kaye, and drummer Hal Blaine. The name of this loose collective? The Wrecking Crew!

This is, of course, the title of the Matt Helm film that featured the real Sharon Tate as Dean Martin’s co-star. In Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, the fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate perform in The Wrecking Crew at the Bruin Theater in Westwood.

The fact that the film and the group of session musicians shared the same name is really just a coincidence. Long before Dean Martin played a knockoff James Bond, author Donald Hamilton featured the character in a series of novels that aimed to rival the success of Ian Fleming’s books. Tate’s The Wrecking Crew takes its name from Hamilton’s 1960 novel.

In contrast, Hal Blaine popularized the name, the Wrecking Crew, in his memoir about the group. Other members, though, have reported that the collective went by other names, such as the Clique and the First Call Gang. Since the group was known by different names, it is hard to know how widely circulated “The Wrecking Crew” was as a particular moniker, even as late as 1969.

So it might be just happenstance that Sharon Tate not only lived in the same house as Melcher, but that their reputations within the entertainment depended upon their association with “wrecking crews.” Still, given the prominent role The Wrecking Crew plays in Tarantino’s film, I find it hard to believe that he wasn’t aware of this connection. Indeed, I suspect he really relished its irony.

The buzz surrounding Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood has not subsided much after its release. (Consider the items listed above as a little more fodder for those water cooler conversations.) As Tarantino’s most personal film, it remains a love letter both to the city of Los Angeles and to the popular culture of his youth.

It’s also a portrait of an industry in the midst of change and so offers an interesting perspective on our current historical moment. As several major studios prepare to launch their own streaming services, Tarantino’s fondness for 35mm projection and “appointment” television may look even more nostalgic just a few years from now. Yet even as the contemporary film and television industries gear up for further change, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood is a vivid demonstration of the power of popular storytelling. It reminds us that Hollywood is much more than a place. It’s a state of mind.

A recent analysis of Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood’s box office prospects can be found here.

The opening of The FBI episode, “All the Streets are Silent,” can be found here. A video essay discusses Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham’s long professional association – and its influence on Tarantino. For those who want to see Dean Martin in action while wearing that white suit, check this excerpt from The Wrecking Crew. Hal Blaine’s memoir on his years with the Wrecking Crew can be found here.

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019).

Posted in Directors: Tarantino, Film comments, Film music, Hollywood: Artistic traditions |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Twice upon a time . . . in Hollywood: Jeff Smith revisits Tarantino’s retro opus open printable version

| Comments Off on Twice upon a time . . . in Hollywood: Jeff Smith revisits Tarantino’s retro opus

Monday | August 19, 2019

DB here:

Can a storyteller be maladroit in using his or her medium and still be worth reading? Can a novelist with a clumsy style be a “good writer”? I’ve posed this question before on this site, and developed an argument about it at length in our book on Christopher Nolan.

Here’s a test case. These are real sentences from books by a novelist many consider one of the great crime/mystery writers of all time.

The knob felt cold and glibly elusive under his touch.

His face was an unbaked cruller of rage.

La Bruja lidded her eyes acquiescently.

I began treacherously touching up my hair via the mirror.

I crawled up onto the seat by means of my hands.

She could feel her chest beginning to constrict with infuriation.

This time the man got up off the bench, taking Quinn’s hand on his shoulder along with him.

Smoke suddenly speared from her nostrils in two malevolent columns. She looked like Satan. She looked like someone it was good to stay away from.

I was probably just a blurred bottle-green offside to her retinas.

“Made it,” Joan Bristol exhaled relievedly.

Seconds went by in packages of sixty.

The foaming laces that cascaded down her were transparent as haze against the light bearing directly on her from the room at her back. Her silhouette was that of a biped.

These passages, and many more like them, were published in books issued by major houses and still in print today. Can anything redeem them?

I’m currently trying to write a book on principles of popular narrative, with a focus on genres of crime and mystery. The project stems from arguments in Reinventing Hollywood and The Way Hollywood Tells It, but I wanted to broaden my inquiry to include theatre and literature as well. One section is about crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s. So naturally I had to include the widely renowned Cornell Woolrich.

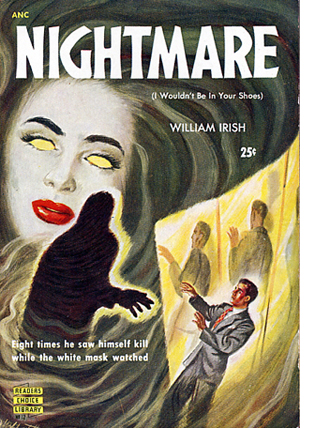

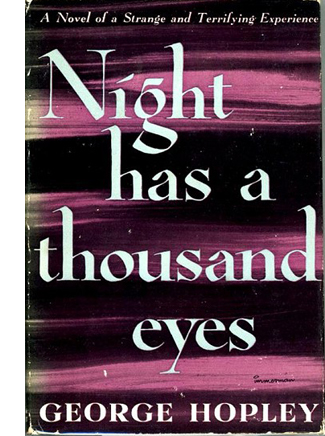

Despite his struggles with syntax and word choice, Woolrich has been a perennial source of popular storytelling. Nearly all the novels were brought to the screen soon after publication, and radio versions of the books and short stories were plentiful. By the 2010s his work had inspired over a hundred movies and television shows (directed by, among others, Hitchcock, Truffaut, Fassbinder, and Jacques Tourneur).

That research has led me two further questions. Are there aspects of his work that counterbalance howlers like those above? And what might have led to those stylistic problems? Readers looking for more direct and detailed studies of film versions of his work can go to Francis M. Nevins’ exhaustive biography and Thomas C. Renzi’s careful consideration of adaptations. (And my studies of The Chase, if you want.) Meanwhile, tackling the questions that interest me, I’ll touch on aspects of cinema a little bit. File this blog under Questions of Narrative Across Media.

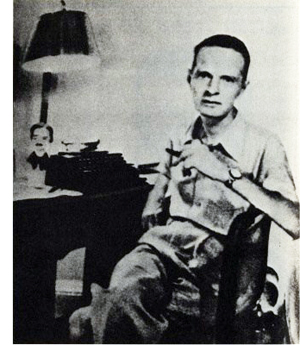

Breathless reading

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity. Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Despite his distinctive sensibility, Woolrich epitomizes some broader narrative strategies of his time. Like all popular writers, he inherited situations, techniques, and themes. To present a bleak, aching world of precarious love and doomed lives, he twisted those conventions into eccentric shapes that added to the Variorum of 1940s mystery storytelling.

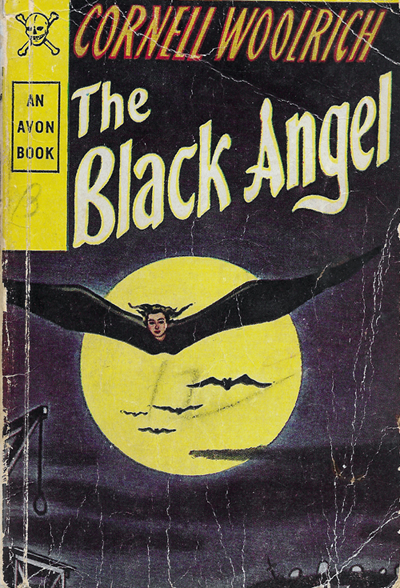

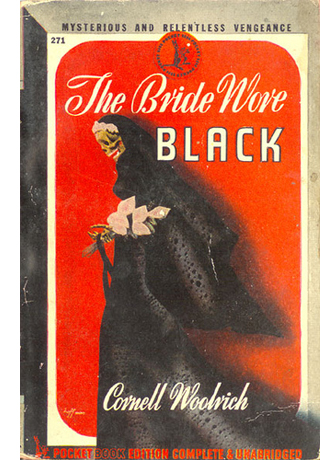

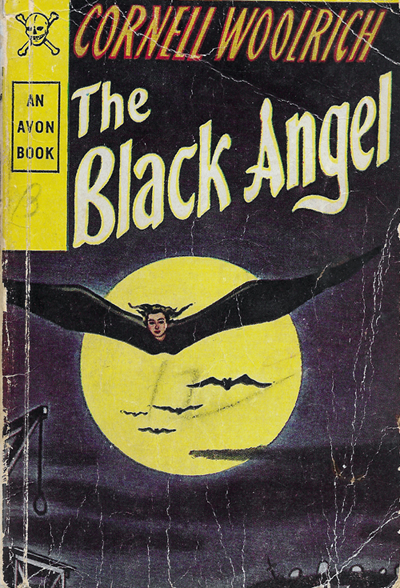

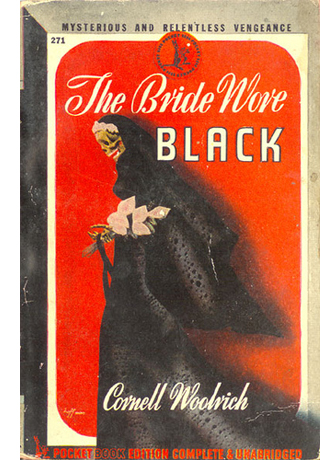

For him, one bout of amnesia isn’t enough, so The Black Curtain (1941) doubles it: the hero, already having forgotten his previous identity, is clobbered by some falling bricks and now can’t remember who he just was. The prototypical serial killer of the 1940s is a man, but The Bride Wore Black (1940) lets a woman stalk her victims. Most thriller novelists are content to put one woman in jeopardy per book, but Black Alibi (1942) lines up six. Alternatively, when a woman tries to save her husband from the chair by investigating four suspects, she’s plunged into danger every time she meets one (The Black Angel, 1943).

Woolrich’s plots flout police procedure (his cops are exceptionally willing to help suspects), and the authorities often flounder. Suspense thrillers usually invoke the supernatural only to dispel it, but in Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945) the authorities fail to save a life because one old man really can predict the future. Not that amateur sleuths fare much better. The unheroic hero of The Black Path of Fear (1945) could hardly be more ineffective; he has to be rescued by the Havana police.

Sometimes the straining for originality snaps. Critics have long pointed out improbabilities and contradictions in the plots. Woolrich’s most devoted chronicler, Francis M. Nevins, warns of “chaotic ambiguities.” The chronology of Rendezvous in Black (1948) is impossible, while the climactic revelation of I Married a Dead Man (1948) is arguably incoherent. Convenient coincidences abound. Add to this a hypertrophied style that in every book slips into unabashed weirdness. (See above.)

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever. Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Admiring readers excuse the faults by testifying that Woolrich’s evocation of tension keeps the pages turning. “Headlong suspense created by total, unrelieved anxiety,” noted Jacques Barzun. “Breathless reading is the sole pleasure.” Raymond Chandler called him the “best idea man” among his peers, but admitted, “You have to read him fast and not analyze too much; he’s too feverish.”

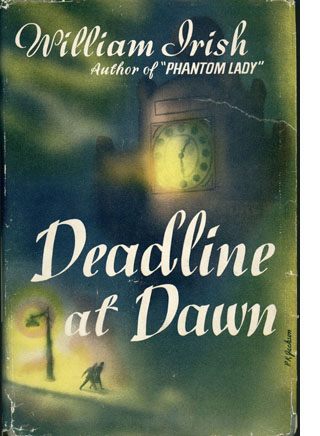

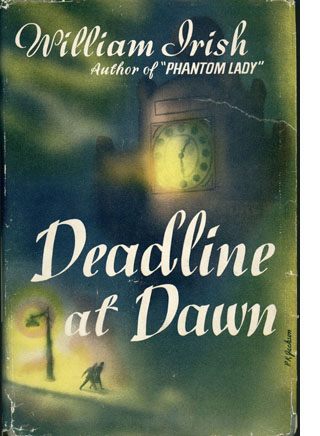

What keeps us reading? For one thing, the outré story situations. A couple hurrying to leave New York must clear the man of murder before the bus leaves (Deadline at Dawn, 1945). A killer stalks a city, but it’s not a human: it’s (apparently) a black jaguar escaped from a sideshow (Black Alibi). A mail-order bride seems unacquainted with things she wrote in her letters (Waltz into Darkness, 1947). Most famously, a man laid up in his apartment thinks he sees traces of a killing through a window across the courtyard (“Rear Window,” 1942).

Outrages to plausibility carry their own allure. What, we ask, might come of these wild mishaps? A train crash kills a husband and his pregnant wife. In the melée an abandoned woman, also pregnant, is mistaken for her and welcomed by the husband’s family. Conveniently, the in-laws have never seen the wife (I Married a Dead Man, 1948) A man accused of murder has an alibi, to be provided by a woman he met in a bar and took to a show. Trouble is, she’s vanished. All the witnesses deny she existed (Phantom Lady, 1942).

The development of the action also presents intriguing reversals. The man gulled by the fake mail-order bride falls in love with her. People who claim not to have seen the phantom lady wind up dead. The woman trying to exonerate her husband falls in love with the real killer and dreams about him even after he has killed himself.

The game is afoot

Woolrich’s novels tend to rely on two basic plot patterns, both based on the hunt. In one, amateurs try to solve a crime and move from suspect to suspect. Our viewpoint is mostly tied to the investigators. In the other pattern, a serial killer stalks a string of victims, and here Woolrich is more innovative. Normally, the serial-killer plot either concentrates on the killer’s viewpoint, as in the novels Hangover Square (1941) and In a Lonely Place (1947), or concentrates on the investigators, as in Ellery Queen’s Cat of Many Tails (1949). A few constantly bounce the spotlight among all the parties—killer, victims, and investigators—as in Fritz Lang’s film M (1931) and Philip MacDonald’s novel X v. Rex (1933).

Woolrich by contrast emphasizes the victims’ viewpoints. The killer might appear only at the beginning and end (Rendezvous in Black) or get introduced at intervals in brief, objective scenes (The Bride Wore Black). Less space is devoted to the investigators, although they gain prominence as the crimes pile up. Woolrich puts his energies into building waves of suspense as one target after the other confronts death.

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure. The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

Something else now assailed her, again from without herself, but of a different sensory plane than hearing this time. A prickly sensation of being watched steadily from behind, of something coming stealthily but continuously after her, spread slowly like a contraction of the pores, first over the back of her neck, then up and down the entire length of her spine. She couldn’t shake it off, quell it. She knew eyes were upon her, something was treading with measured intent in her wake.

This passage is part of a ten-page account of the woman’s wary progress through a night street, rendered wholly from her viewpoint.

Woolrich’s other basic plot pattern, the investigation of a murder, plays up the role of fear as well. His amateur detectives, lacking official firepower, are constantly facing danger from the suspects they track.

Fright was like an icy gush of water flooding over them, as from burst pipe or water-main; like a numbing tide rapidly welling up over them from below. [Deadline at Dawn]

In both of his favored plot schemes, the plunges into characters’ minds and bodies help fill out a full-length novel. If you play down other lines of action (professional police investigation, killer’s mental life), you need to dwell on the reactions of the victims or amateur detectives.

Yet this very emphasis is one source of the stylistic howlers. In expanding his suspense scenes, Woolrich’s prose sometimes fails him. Needing to spin out lots of words evoking an ominous atmosphere, he’s tempted to pileups like this:

And the path that had led me to it through the night had been so black and so full of fear, and downgrade all the way, lower and lower, until at last it had arrived at this bottomless abyss, than which there was nothing lower. [The Black Path of Fear]

Such rodomontade carries the 1940s emphasis on subjectivity to paroxysmic limits.

He recruits other techniques of popular storytelling. They keep his action moving forward through time and plunging inward into the unfolding scenes. And some can help mask story problems.

By hinging his story around a search for a killer or a victim, Woolrich’s plots tend create a string of one-on-one encounters. Rather than disguising the episodic quality of these, he sharpens them by breaking the action into distinct blocks. Those blocks are presented as a checklist agenda, Woolrich’s equivalent to the closed circle of suspects we find in the classic weekend-house-party detective story.

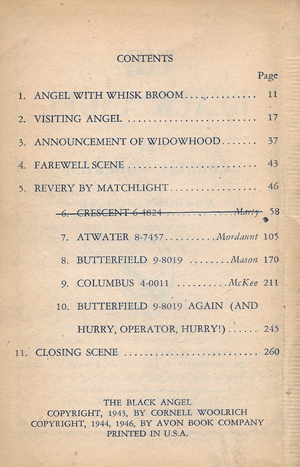

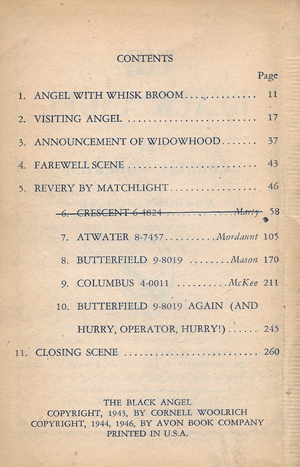

The Black Angel is a simple instance.

After an initial cluster of five chapters presenting Kirk Murray sentenced to death, we follow Kirk’s wife Alberta as she seeks the true killer. Her efforts are given in five parallel chapters, each indented and tagged with a telephone number. One that Alberta finds scratched out in an address book is presented just that way in the chapter title: “Crescent 6-4824.” Because at the climax she returns to one of the four suspects, another title gets recycled: “Butterfield 9-8019 Again (And Hurry, Operator, Hurry!).”

A more complicated example of modularity is The Bride Wore Black. It’s broken into five parts, each titled with the name of a victim. Each part contains three sections.

“The Woman” shows the vengeful bride launching a new false identity. The part’s second section, titled with the victim’s name, shows how the murder is accomplished. A third section offering “Post-Mortem” on the victim consists of documents and conversations among the police. Viewpoints are rigidly channeled as well. Each “Woman” section is handled in objective description, while each victim section presents the targeted man as the center of consciousness. The book could be mapped out on a spreadsheet.

The modular layout and rigorous moving-spotlight narration risk choppiness, yielding something like a set of short stories. But the tidy exoskeleton can make the plot seem rigorously organized, even while it masks problems of time and causality. And the very arbitrariness of the pattern creates a sort of meta-curiosity. Like the teasing tables of contents in 1920s and 1930s detective fiction, a Wooolrich checklist of suspects or victims makes us aware of a larger rhythm. How will this pattern be filled out?

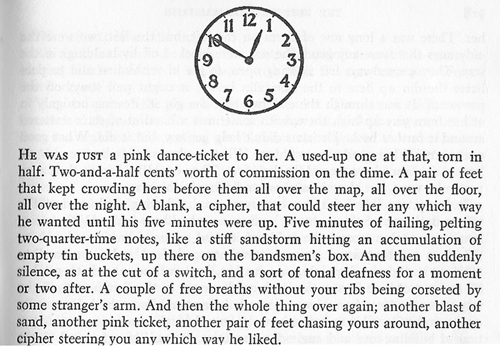

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure. An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

Facing a ticking clock wedded to a clear-cut pattern, we become sensitive to variations among the modules. The victim-centered chapters of The Bride contrast the personalities and private lives of the male victims, along with Julie’s resourceful methods of murder, and the last chapter breaks the three-part format by inserting a flashback dramatizing the fatal wedding. Rendezvous in Black revives the shooting-gallery structure of Black Angel and The Bride, adding a schedule that sets each murder on May 31st of different years. Within this regularity (“The First Rendezvous,” etc.), viewpoints multiply gradually so that the interplay of characters’ range of knowledge becomes richer.

The modular structure shows up in milder ways. Black Alibi tags its chapters with victims’ names and concentrates on one woman’s terror at a time, with each chapter concluding with an exchange among investigators. Deadline at Dawn and Phantom Lady alternate scenes between two characters embarked on parallel investigations. Night Has a Thousand Eyes, in some ways the most ambitious of the books, embeds the checklist within the police investigation. As teams of cops trace parallel leads, their efforts are crosscut with the target under threat, waiting with his daughter and a cop.

A simpler, more poignant, rhyme-and-variations effect is supplied by a prologue and epilogue in I Married a Dead Man. The prologue’s first-person narration, set off from the central chapters’ third-person narration, finishes: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. We’ve lost, we’ve lost.” An epilogue rewrites the prologue and yields closure: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. And now the game is through.” In such ways, Woolrich brings the overt compositional symmetry of both “serious literature” and the puzzle-driven detective story into the thriller.

Sweating the small stuff

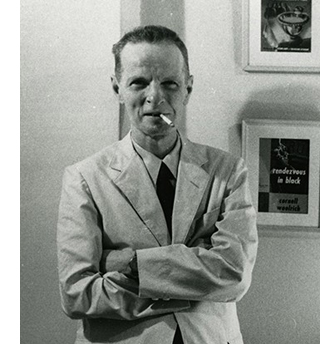

Henry James, 1913; Cornell Woolrich, ca. 1927.

By the 1920s, ambitious Anglo-American writers in both popular genres and “advanced” literature had fallen under the sway of a new model of the novel. Henry James had argued that if the novel was to be a true art form, it needed more compositional rigor, a patterned architectural solidity. He also advocated for a self-conscious control of viewpoint and a greater commitment to concrete presentation of action. (“Dramatize, dramatize!”) A little later, Joseph Conrad’s books had demonstrated the power of shifting viewpoints and multiple narrators, as well as an emphasis on the power of sight.

Popular writers of the nineteenth century, notably Dickens and Wilkie Collins, had already made use of some of these techniques, as did more highbrow efforts, like Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). But in the wake of James and Conrad, tastemakers erected these principles into strict norms for well-made novels. These precepts were set out explicitly in Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1922), and they were picked up in popular writing manuals as well.

Many mainstream fiction writers (and dramatists) took up the techniques promoted by the James-Conrad-Lubbock tradition. Middlebrow novels employed block construction, played with multiple viewpoints, and included an explicit “exoskeleton” of labeled parts pointing up a self-conscious architecture. Joseph Hergesheimer’s Java Head (1919) spreads nine characters’ viewpoints across ten parallel chapters. Detective fiction wasn’t immune to the new methods. Conrad’s exploration of optical viewpoint has a contemporary counterpart in the Chestertonian grandeur of the mystery story “The Hammer of God” (1910). Father Brown is standing at the top of a church.

Immediately beneath and about them the lines of the Gothic building lunged outwards into the void with a sickening swiftness akin to suicide. . . . When they saw [the church] from below, it sprang like a fountain at the stars; and when they saw it, as now, from above, it poured like a cataract into a voiceless pit.

The writers of High Modernism revised the James-Conrad-Lubbock norms, pushing toward more difficult manipulations of time, viewpoint, and subjective states. Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury assigns different narrational voices to its four-block layout, but these make the story world and the time scheme opaque. (Even if you master the stream-of-consciousness technique, you still have to figure out that one character is called by two names and two characters have the same name.)

Like many other writers, Woolrich pulls several post-James techniques into genre literature. His block construction, marked by strict times and viewpoints, along with his labeling of plot phases, owes something to this tradition, as well as to the clever construction of detective stories of the 1920s and 1930s (Ellery Queen, Anthony Berkeley, et al.). He borrows another narrative strategy as well: granular scene description keyed to a character’s sensations and feelings. We get a kind of hypertrophy of Lubbock’s “Show, don’t tell.” In reply to James, Woolrich in effect declares, “Overdramatize, overdramatize!”

In his uncompleted autobiography, Woolrich reflected on his early efforts to compose scenes. A man takes a hotel elevator, and instead of writing, “He got in, the car started; the car stopped at the third and he got out again,” the young Woolrich would pad the trip out to a page or more. This was amateurish, he thought at the end of his life. Yet this sort of expansion of action moment by moment is a hallmark of his 1940s novels. Perhaps it’s what Chandler had in mind when referred to Woolrich “getting deep into every scene.”

As we’ve seen, moments of terror and suspense are rendered in detail. So are the necessary touches of atmosphere. In The Black Path of Fear, the man on the run has told his story to Midnight. As we’ve seen, moments of terror and suspense are rendered in detail. So are the necessary touches of atmosphere. In The Black Path of Fear, the man on the run has told his story to Midnight.

When I’d finished telling it to her the candle flame had wormed its way down inside the neck of the beer bottle, was feeding cannibalistically on its own drippings that had clogged the bottle neck. The bottle glass, rimming it now, gave a funny blue-green light, made the whole room seem like an undersea grotto.

We’d hardly changed position. I was still on the edge of her dead love’s cot, inertly clasped hands down low between my legs. She was sitting on the edge of the wooden chest now, legs dangling free. . . .

The behavior of light, the insistence on color, the description of the characters’ postures and gestures—these are typical of Woolrich’s scenes.

Even the simplest action employs Lubbock’s “scenic method” to a disconcerting degree. To quote adequately would take pages, but some samples can suggest just how distended and detailed even minimally functional scenes are.

I reached out for a little lamp he had there close beside the bed and clicked it on. Twin halos of light sprang out, one at each end of the shade, and showed up our faces and a little of the margin around them. The shade itself was opaque, to rest the eyes.

Then I just sat back and waited for the shine to percolate through to him, sitting on the bias to him. It took some time. He was sleeping like a log. [The Black Path of Fear]

Any other writer would have retained just the first sentence and the last (but maybe not with the clichéd phrasing). Who cares about the design of a light fixture, or whether the shade rests the eyes? Yet Woolrich feels the need to show and tell as much as he has room for.

A woman comes to a Bowery bar looking for a murder suspect. After a page and a half of banter with the bartender, she finds her quarry hunched over a tabletop. Another page is devoted to rousing him.

He moved slightly, and I saw him looking downward at the floor around his feet. Looking around for something on that filthy place where people stepped and spat all day long. In a moment more I had guessed what he was looking for and I opened my handbag and took out the cigarettes I had provided myself with and held the package ready, with one protruding, as my first silent overture.

His eyes stopped roaming suddenly, and they had found the small arched shape of my shoe, planted there unexpectedly on that floor beside him, and the tan silk ankle rising from it. [The Black Angel]

It takes another page for the drunk to accept the cigarette, and three more for the woman to question him. But he’s too incoherent, so she parks him in a hotel and resumes questioning him the next day—a process that takes fifteen pages and includes detailed descriptions of the hotel room, the light filtering in, and the two characters’ shifting positions in space.

This writer has Roderick Usher’s “morbid acuteness of the senses.” Scenes are thick with smells and sounds. One virtuoso section of Rendezvous in Black is all noises and speech because our center of consciousness is a blind woman. Above all, Woolrich’s scenes revel in optical point of view.

Movies on the page

Sometimes the observer is imaginary, looking at things alongside the character. Detective Wanger enters a murder scene.

They seemed to be playing craps there in the room, the way they were all down on their haunches hovering over something in the middle of the floor. You couldn’t see what it was, their broad backs blotted it out completely. It was awfully small, whatever it was. Occasionally one of their hands went up and scratched the back of its owner’s rubber-tired neck in perplexity. The illusion was perfect. All that was missing was the click of bone, the lingo of the dicegame. [The Bride Wore Black]

Actually, the policemen are interrogating a boy whose father has been murdered. Presumably Wanger doesn’t take the huddle for a craps game. We’re given the mistaken impression of a novice observer who’s watching from a particular angle.

More often, it’s the character who occupies a definite station point, determined by foreshortening and perspectival distortion. The supreme example is of course the short story “Rear Window” (1942) whose original title was “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” One of his clumsy passages in another story tries for the same kind of positioning: “He turned and looked up, startled, ready to jump until he’d located the segment of her face far up the canal of opening between them.”

Woolrich’s interest in the geometry of looking, what can and can’t be seen, finds a natural home in eyewitness plots, of which there were several in 1940s film and fiction (and even radio). In “Rear Window,” the protagonist Jeff tracks his neighbor’s progress from window to window as if studying an Advent calendar. Woolrich strives to capture the exact geometry of Jeff’s field of view. Woolrich’s interest in the geometry of looking, what can and can’t be seen, finds a natural home in eyewitness plots, of which there were several in 1940s film and fiction (and even radio). In “Rear Window,” the protagonist Jeff tracks his neighbor’s progress from window to window as if studying an Advent calendar. Woolrich strives to capture the exact geometry of Jeff’s field of view.

There was some sort of a widespread black V railing him off from the window. Whatever it was, there was just a sliver of it showing above the upward inclination to which the window sill deflected my line of vision. All it did was strike off the bottom of his undershirt, to the extent of a sixteenth of an inch maybe. But I hadn’t seen it there at other times, and I couldn’t tell what it was.

Jeff’s tightly focused attention contrasts with his neighbor Thorwald’s casual sweeping looks toward the courtyard. The climax will come when Thorwald realizes he’s been Jeff’s target, and Jeff sees in the murderer’s look “a bright spark of fixity” that “hit dead-center at my bay window.”

A similar effect occurs at the climax of “The Boy Cried Murder” (aka “Fire Escape”) of 1947, the source of the film The Window (1949). Buddy has been sleeping on a fire escape and is awakened by a murder he watches through a slit in the window shade. The woman comes toward him.

She started to come over to where Buddy’s eyes were staring in, and she got bigger and bigger every minute, the closer she got. Her head went way up high out of sight, and her waist blotted out the whole room. He couldn’t move, he was like paralyzed. The little gap under the shade must have been awfully skinny for her not to see it, but he knew in another minute she was going to look right out on top of him, from higher up.

Again, there’s a stylistic slip (of course she’ll be higher up if she looks out on top of him), but it’s a byproduct of an effort to capture a character’s optical viewpoint.

Sometimes that effort seems pure gimmickry.

I hurried down the street, and the intermittent sign back there behind me kept getting smaller each time it flashed on. Like this:

MIMI CLUB

Mimi Club

mimi club

I could tell because I kept looking back repeatedly, almost in synchronization with it each time it flashed on. . . . [The Black Angel]

Yet even the gimmick seems an effort toward a peculiar kind of vividness—that of a film. The passage imitates alternating shots of the woman looking and the withdrawing club sign. If Woolrich’s modular structure is indebted to strains in modernism and popular fiction, the dense, over-visualized scenes inevitably suggest cinema.

Woolrich worked as a Hollywood screenwriter for a few years and had a lifelong affinity for movies. The books often use cinematic analogies and metaphors, and the characters are frequent moviegoers. (In a 1936 story, “Double Feature,” a gangster takes a woman hostage in a projection booth.) Supposedly Woolrich spent his last years holed up drinking and watching old films on TV. No surprise, then, that some passages echo the look and feel of Hollywood scenes.

Granted, many writers, highbrow and lowbrow, were imitating cinema in Woolrich’s day. Some incorporated filmlike montage sequences to suggest dreams and stream of consciousness. But Woolrich goes farther than most. In Fright (1950), two paragraphs headed “Still Life” survey an empty room that shows signs of interrupted activity—a crumpled newspaper, a note, a burning cigarette, a swaying lamp chain. The passage mimics the sort of tracking shot over details we find in 1940s cinema, continuing for a page until it climaxes in a close-up panning over a body jammed against the door.

When a man realizes his beloved woman lies dead on the bed, a dash can imitate a cut:

But her eyes were still blurry with slee—

His hand stabbed suddenly downward toward the hairbrush, there before her. [Rendezvous in Black]

In Night Has a Thousand Eyes, a woman waits in her car while her father visits the telepath over a period of weeks. Each brief scene starts with the same imagery and phrasing, creating a string of rhyming “shots” across three pages. In Night Has a Thousand Eyes, a woman waits in her car while her father visits the telepath over a period of weeks. Each brief scene starts with the same imagery and phrasing, creating a string of rhyming “shots” across three pages.

I sat there waiting for him, cigarette in my hand, light-blue swagger coat loose over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, rust-colored swagger coat loose over my shoulders. . . .

I sat their waiting for him, plum swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, fawn swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, green swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, black swagger coat over my shoulders, as I’d already sat waiting so many times before.

The modular approach ruling the books’ overall architecture gets carried down into the texture of scenes, creating parallel mini-blocks that convey the daughter’s anxious acquiescence to her father’s obsession.

Woolrich’s literary optics have strong affinities with cinema. We get an effort to mimic a subjective tracking shot as one heroine circles a garden.

The little rock-pool in the center was polka-dotted with silver disks, and the wafers coalesced and separated again as if in motion, though they weren’t, as her point of perspective continually shifted with her rotary stroll. [I Married a Dead Man]

Likewise, a woman approaching a man slowly tapers into focus.

She was up to him eye to eye before he could even take her in in any kind of decent perspective. His visualization of her had to spread outward in concentric, radiating circles for those eyes, staring into his at such close-range.

Brown eyes.

Bright brown eyes.

Tearfully bright brown eyes.

Overflowingly tearful bright brown eyes.

Suddenly a handkerchief had come up to shut them off from his for a moment, and he was able to steal a full-length snapshot of her. Not much more. [The Black Curtain]

This is just showboating, but it’s uniquely Woolrich showboating.

The same goes for a passage struggling to describe people at a bar as if they were framed in the flattening view of a telephoto shot.

There were eight people paid out along it. They broke into about three groups, each self-contained, oblivious of the others, but he had to look close to tell where the divisions came in. Physical distance had nothing to do with it; they all stretched away from him in an unbroken line. It was the turn of the shoulders that told him. The limits of each group were marked by a shoulder turned obliquely to those next in line beyond. They were like enclosing parentheses, those shoulders. In other words, the end men in each group were not postured straight forward, they turned inward toward their own clique. The groupings broke thus: first three, then a turned shoulder, then three again, then another turned shoulder, then finally two, standing vis-à-vis. [Deadline at Dawn]

Few writers would strive so hard to capture the exact look of figures in space. It will take another page for the viewpoint character to realize that a left-handed drinker has stepped out, because one beer mug isn’t empty and the handle is pointing in a different direction than the others.

It’s not hard to imagine such scenes as Hitchcockian POV shots. In Waltz into Darkness, Durand notices a colonel and his lady in the reflection of the “thick, soapy greenish” window of a café. At first the view yields a blob sporting “three detached excrescences”: a feather in a hat, a bustle, and “a small triangular wedge of skirt.” Eventually this monstrosity draws away “into perspective sufficient to separate into two persons.” Conrad’s “impressionism,” aiming to capture the limits of physical point of view, reaches a new height with Woolrich’s account of exact but imperfect vision.

Some provisional answers to my Woolrich questions run like this. The ingenuity of structure and the inherent fascination of the situations somewhat offset the problems of style. Most of his novels tap our primal interest in the hunt, and if things don’t always pay off neatly, the pursuit has enough detours, hurdles, and pitfalls to sustain interest.

And the writing isn’t totally disastrous. There are well-written passages in every Woolrich novel. Many of the howlers arise from the keyed-up emotion he tries to squeeze out of every scene. Others stem from sheer overwriting and padding, and probably the habit Fisher notes of seldom revising. But other errors are a byproduct of his effort to put every bit of action starkly before us. Straining for sensory vividness lures him into clumsiness (“triangular wedge,” as if all wedges weren’t triangular).

More generally, in both virtues and faults, he displays a dogged, frenzied obedience to the narrative traditions he inherited, and an urge to innovate within them, however eccentrically. Henry James asserted that “a psychological reason is, to my imagination, an object adorably pictorial.” A Woolrich character puts it in a typically convoluted way: “Every time you think of anything, there’s a picture comes before you of what you’re thinking about.”

Beyond the books of Nevins and Renzi, valuable appreciations of Woolrich include Nevins’ essay in his collection Cornucopia of Crime: Memories and Summations (Ramble House, 2010), 53-71; Geoffrey O’Brien’s comments in Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir, second ed. (Da Capo, 1997), 97-100; and James Naremore’s essay on his site, “An Aftertaste of Dread: Cornell Woolrich in Noir Fiction and Film.” For a topical overview of Woolrich’s output, see Mike Grost’s entry on him.

I took Steve Fisher’s account of Woolrich’s writing process from “I Had Nobody,” The Armchair Detective 3, 3 (1970), 164. The quotation from Jacques Barzun comes from Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor, A Catalogue of Crime, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 561. The Raymond Chandler remarks appear in a 1949 letter to Alex Barris in Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Plainview, New York: Books for Libraries, 1971), 55. I’ve discussed Mitchell Wilson’s essay, “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1 (January 1947) at greater length in the online essay “Murder Culture.” More generally, Woolrich’s narrative strategies accord with several I chart in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, including the notion of the Variorum.

Woolrich’s early, Fitzgerald-influenced novels reveal seeds of the style to come. A random page from Manhattan Love Song (1932) yields a scene of the hero talking to two women: “Instantly I saw a gleam of admiration light each of their four eyes.”

Astonishingly, Woolrich’s prose glitches don’t rate a mention in Bill Pronzini’s hilarious compilations of bad writing, Gun in Cheek: A Study of “Alternative” Crime Fiction (Coward McCann, 1982) and Son of Gun in Cheek (Mysterious Press, 1987). Pronzini tactfully limits his citations of the classics, only mentioning one Raymond Chandler line: “In spite of his weathered appearance, he looked like a drinker.” Pronzini can find no faults in my personal Style canon: Rex Stout, Donald Westlake (here and here), and Patricia Highsmith.

There’s more on these issues in the entry “The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks.” I discuss The Window in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Film and other media, Film genres, Narrative strategies, Narrative: Suspense |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Cornell Woolrich: The overstrained imagination goes to the movies open printable version

| Comments Off on Cornell Woolrich: The overstrained imagination goes to the movies

Friday | August 9, 2019

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Jeff Smith here:

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood might turn out to be the buzziest film of 2019. Some of this water-cooler talk is due to its unusual status within an ever-enlarging field of true crime stories. (Call it a “not quite true” crime story.) Indeed, the genre is hotter than ever thanks to a bevy of new podcasts, telefilms, and miniseries.

Industry analysts, though, are also keen to interpret Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office fortunes. As that rare big summer release that is neither a sequel nor a franchise title, it can be seen as a test of whether original content can survive amidst heavily marketed, presold tentpoles.

The lesson so far? To quote William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything.” In The Washington Post, one unnamed studio executive warned, “I don’t see any blue-sky meaning here.” The executive added, “This movie has assets that almost no other film has. That’s what drove it.” At least one of those assets is Tarantino himself, who is a brand, if not a franchise. Fans know what to expect in a Tarantino film, which is why the film is sui generis when it comes to this summer’s slate. Due to its unique IP, it can’t really be compared with films like Men in Black International or Spider-man: Far from Home. Yet thanks to Tarantino’s larger than life presence, it also isn’t Long Shot or Booksmart or Stuber.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is catnip to Tarantino nerds like me. It has the usual surfeit of references to obscure films and television shows. Some of these are deftly interwoven into the story itself. It boasts a carefully curated soundtrack that unearths “some-hits” wonders. It also contains scenes depicting nasty yet comical violence, a hallmark of Tarantino’s work ever since Reservoir Dogs.

At first blush, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would seem to be Tarantino’s most linear film. Yet it still displays certain continuities with his oeuvre in terms of story structure and technique. Although the film eschews the chapters and title cards found in Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, it still contains elements of what David calls “block construction.” In the case of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, it is all about threes. The plot is structured around three days in the winter and summer of 1969: February 8th, February 9th, and August 9th. Each “chapter” is introduced showing the date via superimposed text. And all three chunks of narrative crosscut among the activities of three actors – Sharon Tate, Rick Dalton, and Cliff Booth – as they try to adapt to changes in the film and television industries.

If all of this assures that you’d never mistake Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as the work of another director, other elements show Tarantino striking out in new directions. Chief among these is his mash-up of two normally distinct story types: the show-biz tale and the true crime yarn. Think of it as Singin’ in the Rain meets In Cold Blood. In what follows I outline some of the ways that Tarantino adapts his signature style to two well-established storytelling options: the multiple draft narrative and the network narrative. I also consider the effects Tarantino’s counterfactual history has on the conventions of the show-biz tale and the celebrity biopic.

My analysis contains major spoilers. If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, stop reading now!

My world and welcome to it

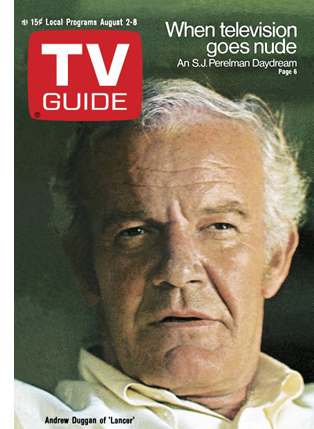

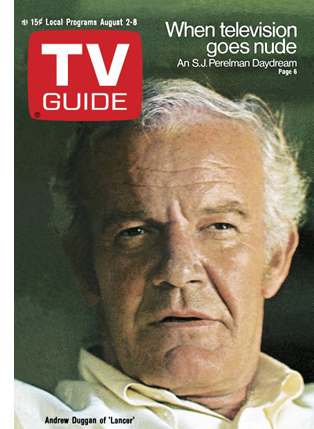

Quick trivia question: what actor was on the cover of TV Guide during the week that Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family? Sharp viewers of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should know the answer. We see Tate’s housemate, Woychiech Frykowski, reading that issue of the magazine as he watches Teenage Monster on late night television.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier. Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Tarantino’s film treats this little bit of pop culture ephemera as an uncanny coincidence. It simply becomes yet another way that he can intertwine the destinies of his three protagonists. But that brief shot got me thinking: did Tarantino start with the idea that he’d recreate whatever series was featured on TV Guide the week Tate was killed?

If so, Rick might have appeared just as easily as an aspiring cartoonist next to William Windom on the NBC sitcom, My World and Welcome to It. The show debuted just six weeks after Tate’s death. It is not unthinkable that NBC would have pushed for a cover on TV Guide in an effort to promote the premiere. Yet Tarantino’s counterfactual history in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would have been vastly different if that had been the case.

Did Tarantino really base his screenplay on this conceit? I doubt it. Lancer fits so snugly into the world that the director captures onscreen that it is not be so easily replaced. Tarantino seems to have a nostalgic fondness for the show, much as I did in my wasted youth. (I recall having a Lancer lunchbox at age six.) Production designer Barbara Ling describes the steps she took to recreate Lancer’s mix of Spanish/Western design. This involved adding adobe storefronts to the wooden ones, and substituting iron coils for wooden pegs on the saloon’s staircase. Ling added, “This was a [rich] cattle town and the buildings are two and three stories. It’s not Deadwood.”

Many critics have characterized Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as another hangout movie. This is Tarantino’s designation for a film that is leisurely paced, fairly light on plot, and mostly gives the audience a chance to spend time with the characters. Indeed, because of these qualities, reviewers often compare Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood to Jackie Brown, a film that Tarantino himself compared to Rio Bravo, which was Howard Hawks’ hangout movie.

The resemblances don’t stop there. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s three-headed protagonist bears certain similarities to Jackie Brown’s Jackie, Ordell, and Max.

Yet while watching Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I felt this film, more than any of Tarantino’s others, was an exercise in world-building. Normally we associate that term with sci-fi, fantasy, and comic book movies. It is especially important for transmedia properties where the fictional universe depicted exceeds the bounds of any individual film, television series, book, or video game.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is also an alternate history, a type of speculative fiction also common in sci-fi and comic book stories. The Avengers: End Game and Spider-man: Into the Spiderverse are both relatively recent examples. This suggests a loose affiliation between Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood and other blockbusters even as Tarantino tweaks that formula by situating his speculative fiction within the generic framework of true crime.

Tarantino largely avoids the industrial motivations behind these two narrative techniques commonly seen in tentpoles. Instead, he simply recreates the pop culture world of his youth. In doing so, the director’s real world, his “realer than real” universe, and his “movie movie” universe all collide.

Keepin’ it real (and realer)

As Tarantino has explained in interviews, the “realer than real” universe is an alternate reality close to our own where his fictional characters can intermingle with real people. The “movie movie” universe, on the other hand, is a more overtly fantastic world closer in spirit to comic books or exploitation films. The characters have unusual abilities or even supernatural powers. The “movie movie” thus downplays the realistic motivations usually found in the “realer than real.” In Tarantino’s oeuvre, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance exemplify the “realer than real.” Kill Bill and From Dusk to Dawn are instances of the “movie movie.”

Each universe features a web of connections that can link particular tales together. For example, Kill Bill’s Sheriff Earl McGraw and his son Edgar pop up in Death Proof. Similarly, Lee Donowitz, the cocaine-sniffing movie producer in True Romance, is purportedly the son of Sgt. Donny Donowitz, the “bear Jew” in Inglourious Basterds.

In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the most obvious references to these two Tarantino universes are the fictional brands he has created. During the end credits, we see Rick in a TV ad for Red Apple cigarettes. According to a Tarantino wiki, “ads or packs of these flavorful smokes” can be seen in The Hateful Eight, Inglourious Basterds, Planet Terror, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, From Dusk till Dawn, Four Rooms and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. (The latter is an obvious outlier. Yet the Red Apple nod was likely an in-joke related to Tarantino’s offscreen romance with Mira Sorvino, who played Romy.)

Similarly, Tarantino’s fictional fast food chain, Big Kahuna Burger, appears on a bus billboard in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. It previously was featured in a memorable scene in Pulp Fiction. (“That’s a tasty burger!”) But it had already debuted as a delicious snack devoured by Mr. Blonde in Reservoir Dogs. Big Kahuna later comes back in two other Tarantino films, From Dusk Till Dawn and Four Rooms, as well as Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.

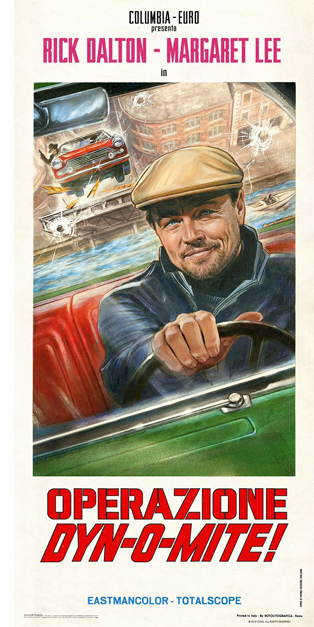

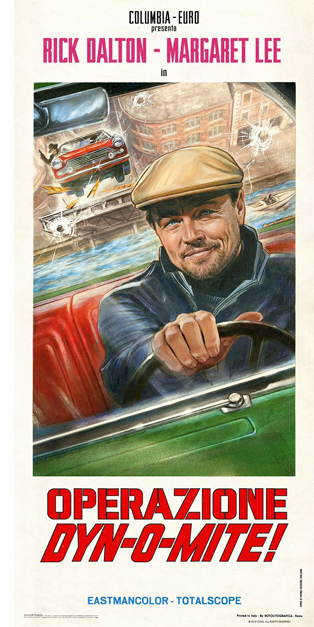

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride. Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Much of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes from the way Tarantino overlays these three universes to create a singular fictional world. For example, at one point we learn that Rick was considered for the role of Captain Virgil Hilts, the part played by Steve McQueen in John Sturges’ The Great Escape. Tarantino even inserts digitally altered footage of The Great Escape to show us a scene of Rick as Hilts. Since Rick claims he never met Sturges, this moment appears to represent an imagined version of the film that could exist in some type of alternate history. It invites us to consider how different Rick’s career might have been had fortune smiled upon him instead of McQueen.

To disentangle this knot, one must surmise that The Great Escape and Steve McQueen belong to both the real world and the “realer than real” world. Yet the scene of McQueen at the Playboy mansion and Rick describing his missed opportunity can only belong to the “realer than real.” And the character of Hilts himself exists only in the “movie movie” world. Hilts shares this status along with other characters Rick plays onscreen, such as Bounty Law’s Jake Cahill and The FBI’s Michael Murtaugh. After all, movie magic enables Cliff Booth to stand-in for Rick for scenes involving physical action. That two actors can play the same character within the same scene suggests that fictional personae in cinema have a unique ontological status quite different from the real world.

Arguably, the scene where Sharon Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew raises even more vexing issues about what is real and what is fictional. Unlike the clip from The Great Escape, the theatre screening shows the real Sharon Tate playing the character Freya in The Wrecking Crew. The fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate, along with the rest of the Bruin Theater’s audience. Yet, because Margot Robbie only pretends to be Sharon Tate for Tarantino’s camera, she doesn’t really watch herself playing the role. Obviously, Robbie belongs only to the real world. Yet Sharon Tate, as both an actual person and a fictional character, inhabits both the real world and the “realer than real world.”

Here the film indulges the Bazinian conceit that cinema has indexical properties. While making The Wrecking Crew, the film camera captured an imprint of the real Sharon Tate that preserved her being beyond the reaches of time and even death. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this moment is both joyful and sad. The viewer imagines the thrill that Tate feels in watching herself on the big screen, basking in the glow of incipient stardom. Yet the delight we experience is colored by our knowledge of what happened to the Sharon Tate seen falling on Dean Martin’s camera case. Unlike Robbie’s character, that Tate is doomed to a grisly death at the hands of psychopaths.

By film’s end, however, we are forced to reevaluate where Sharon Tate fits into Tarantino’s universe. When Cliff and Rick thwart the attack of Tex Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, and Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, both Sharon Tates appear to move solely to the realm of the “realer than real.” Like the fictional Sharon Tate played by Robbie, the actress who appeared in The Wrecking Crew also lives on in a parallel universe created by the forking of time. And the fate of that character remains completely undetermined. Now fully a part of the “realer than real,” Tarantino’s Sharon Tate might eventually snort cocaine with movie producer Lee Donowitz or bum a Red Apple cigarette from Pulp Fiction’s Mia Wallace.

Once she joins the “realer than real,” almost any fate you could imagine for Sharon Tate seems possible. And it is that sense of the actress’ unlimited horizons that gives the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its resonance. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time films always situated viewers in the realm of myth. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, on the other hand, evokes the fairy tale.

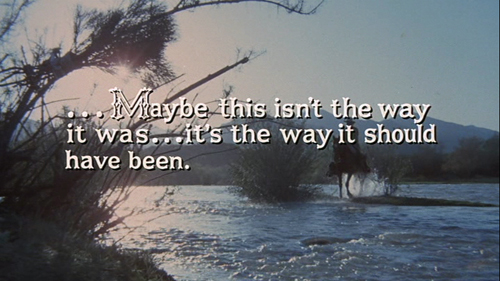

Tarantino is known for his experimentation with narrative, and the simplicity of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s “what-if” scenario could seem like a retreat from the formal play seen in his earlier films. Yet I’d argue that Tarantino’s merging of fact and fiction is even more audacious in certain respects. It strikes me as an unconventional example of what David calls “multiple draft narratives,” like Krzystof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance or Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gives us a second draft of history, albeit one where the key decision point is saved almost until the end of the film. And unlike Blind Chance or Sliding Doors, Tarantino doesn’t need to tell us what the different outcomes are for each of these tales. The first draft of history is one we already know.

In fact, the notion of multiple drafts offers a useful lens for all three films in Tarantino’s “counterfactual” trilogy. (The other two are Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained.) In Groundhog Day, Source Code, and Edge of Tomorrow, each iteration of the basic situation shows the protagonist inching toward his goals. They gradually progress to the point where they are able to alter destiny, either theirs or the world’s or both.

Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood all present images of history not as it was, but as it should have been. Such counterfactual histories run counter to the norms of speculative fictions that often present us with dystopian worlds we were lucky to avoid. (Think Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Robert Harris’ Fatherland, or Kevin Willmott’s “mockumentary” C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.) All of these stories depend upon our knowledge of the first draft of history. Yet Tarantino gives us second drafts that right particular historical wrongs in either small or large measure. In doing so, Tarantino gives us versions of history that are closer in spirit to his favorite movies. All three films in the “counterfactual” trilogy feature tidy resolutions. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, however, is even more self-conscious about the way Tarantino’s second draft of history takes the form of a “movie movie” climax. The realer-than-real version is the one we ought to prefer.

Paging Mr. Melcher, Mr. Terry Melcher…

If Tarantino’s conflation of fact and fiction evokes certain traits of the multiple-draft narrative, his vivid recreation of Hollywood circa 1969 illustrates another type of story popularized in American independent films and various art cinemas: the network narrative.

Tarantino has broached this form before in Inglourious Basterds. There he moves back and forth between three mostly independent storylines: 1) the Basterds’ guerrilla campaign against German soldiers, 2) Archie Hicox and Bridget von Hammersmarck’s initiation of Operation Kino, and 3) Shosanna’s plan to avenge her family’s deaths during the premiere of Nation’s Pride. SS officer Colonel Hans Landa threads through all three storylines. He orders the killing of Shosanna’s family in the opening scene. Later he shares apple streudel with Shosanna in a Paris café. Landa also investigates the scene where Hicox has been killed. In the climax, he interrogates Bridget in a scene that contains a grim allusion to Cinderella’s lost slipper.

Finally, Landa negotiates a deal with Aldo Raine’s superiors that guarantees his immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is obviously much less plot-driven than Inglourious Basterds. Yet, as noted above, it shares a similarity in the way it interweaves the stories of three characters: Rick, Cliff, and Sharon.

It’s frequently said that Hollywood is a company town. By situating all three characters within the film and television industries, Tarantino tacitly stays faithful to that truism. The protagonists’ shared profession also facilitates the kinds of attenuated links between stories commonly found in network narratives.

Part of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes in recognizing the “six degrees of separation” that join all of these people, both real and fictional, in the same entertainment ecosphere. Take, for instance, one decidedly minor character: actress and singer Connie Stevens, played by Dreama Walker. At the Playboy Mansion party, Stevens listens to Steve McQueen explain the romantic triangle that has Sharon living with her current husband, Roman Polanski, and her ex-boyfriend, Jay Sebring. Stevens, though, is the ex-wife of actor James Stacy, who played Johnny Madrid in Lancer. Stacy (played in our film by Timothy Olyphant) is Rick Dalton’s scene partner for the episode of Lancer that Dalton hopes can spur his comeback. Dalton is Sharon Tate’s neighbor on Cielo Drive, the same house that Charles Manson targets as the site of the “family’s” first murder. This circuit even loops back on itself. When Stacy and Dalton first meet on set, Stacy asks Rick whether it was true that he almost got a part in The Great Escape, the same part played by McQueen.

Two characters in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood serve as nodes that connect all three storylines together. The first is Cliff, Rick’s stunt man and gofer. Although not a resident at Cielo Drive, he spends a lot of time in Rick’s home and thus is privy to what happens in Sharon’s abode. This is especially evident when Cliff repairs Rick’s fallen TV antenna. The camera is aligned with him as he overhears Sharon playing a Paul Revere and the Raiders album. He also notices Charles Manson approaching the Polanski residence. Tarantino’s casting of Damon Herriman as Manson is likely an allusion to the television show, Justified. Herriman played Dewey Crowe alongside Olyphant.

Justified was also an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s “Raylan Givens” books. Tarantino has long admired Leonard’s work as a writer of both westerns and crime novels.

Employing a redundancy that befits Hollywood storytelling, Cliff gets linked to Sharon’s storyline in other ways. While working as Rick’s stunt man for an episode of The Green Hornet, he gets involved in a dust-up with Bruce Lee. Lee gave Sharon Tate some pointers on fighting as she prepared for her role in The Wrecking Crew. And in real life, the martial arts legend was recommended for the role of Kato on television’s The Green Hornet by Sebring, Tate’s former boyfriend.

Perhaps Cliff’s most important role in the film’s network involves his dalliance with Pussycat, one of the many young women who viewed Manson as a kind of guru. Cliff picks up Pussycat as a hitchhiker and gives her a ride back to the Spahn ranch. Having worked on the ranch back when it was an active production site, Cliff grows concerned for the safety of its owner, George Spahn. Cliff notices how the Manson clan has taken over and is troubled by its weird vibe. Determined to see George for himself, Cliff forces his way into George’s house over the objections of the Manson girls, especially Squeaky. George seems careworn, but Cliff finds that there is little he can do for him.

When Cliff sees a pocketknife sticking out of his front tire, he confronts Clem, one of Manson’s followers. The conflict becomes physical. Cliff breaks Clem’s nose with one punch and then proceeds to beat him to a bloody pulp.

This proves to be a dangling cause that gets resolved in the film’s climax when Cliff recognizes Tex, Sadie, and Katie as people he met at the Spahn ranch.

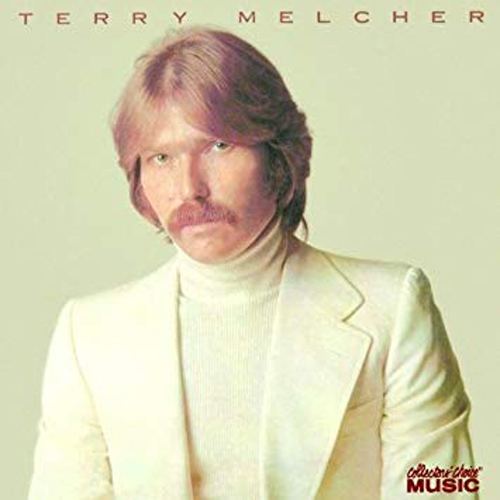

The other character who links the storylines together is one we never see: record producer Terry Melcher. Melcher is the “Terry” that Manson mentions when he visits Cielo Drive in the scene described above. Later, Tex reminds Sadie, Katie, and Linda that Charlie directed them to go to the place where Terry Melcher lived and kill everyone inside.

Although these are the only explicit references to Melcher, he is indirectly represented in several other aspects of the film. Here it helps to know a little about Melcher’s career and Manson lore. Even if Melcher’s name draws a blank, you likely know many of the bands he worked with: the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.

All these musicians crop up in one way or another in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Melcher’s last major credit of the 1960s was as producer of the Byrds’ Ballad of Easy Rider. When Rick berates Tex for parking his car on Cielo Drive, he yells, “Hey, Dennis Hopper! Move this fucking piece of shit!” Rick’s insult fits with his general disdain for hippies. But it also alludes to Easy Rider by comparing Tex’s look to that of Hopper’s character, Billy.

Two of the Mamas and the Papas – Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot – both appear in the party scene at the Playboy mansion.

We also hear the Mama and the Papas’ big hit, “California Dreaming” in a cover version by Puerto Rican singer José Feliciano. And when the car driven by Tex crawls up Cielo Drive, the music issuing from the Polanski residence is the Mamas and the Papas’ “12:30: Young Girls are Coming to the Canyon.” Even before Tex’s directive to the Manson girls, Tarantino has given us a subtle reminder that Melcher was Charlie’s intended, if indirect, target.

Finally, Sharon plays Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Good Thing” and “Hungry” on a hi-fi in her bedroom.

The choice of music is especially fitting since the band’s lead singer, Mark Lindsay, lived in the same house on Cielo Drive with Melcher and his then girlfriend, Candice Bergen.

Beyond these musical references, Melcher’s history with Manson informs Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in another way. Melcher recorded some demos of Manson’s songs, and even discussed making a documentary about Manson’s commune at the Spahn Ranch. In testimony at trial, Melcher said that any possibility of a record contract with Manson was sundered when Charlie asserted that he’d never join a musicians’ union. Manson’s staunch refusal was rooted in his desire to avoid entanglements with the establishment. Yet union membership was a condition for any contract with Melcher’s label, Columbia records. Another factor in Melcher’s decision was his assessment of Manson’s talent. Charlie couldn’t sing.

Although Melcher publicly stated that he only considered Manson’s musicianship, he privately expressed concerns about Charlie’s mental stability. These were heightened when he visited the Spahn Ranch and witnessed Manson in a physical altercation with a drunken stunt man. Tarantino more or less recreates this episode in his film, substituting Cliff for the unnamed stunt man and the hapless Clem for Charles Manson.

More importantly, Melcher is the son of screen legend Doris Day and stepson of agent/manager/producer Martin Melcher. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, he becomes the ideal, if absent, symbol of the combined worlds of music, television, and film that Tarantino so lovingly details.

How the West was lost

Los Angeles circa 1969 is presented as the epicenter of the American entertainment industries. It’s a place where a hairdresser like Jay Sebring rubs shoulders with action stars, TV cowboys, ingénues, film directors, and pop stars –and make $1000 a day to boot! The constant stream of hits from KHJ radio is as ubiquitous as the many movie posters, billboards, and theater marquees that feature Hollywood’s latest and greatest.

Tarantino’s press kit for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood makes reference to Joan Didion’s famous observation in “The White Album” that “the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community.” Most critics take Didion’s reference to the Sixties as shorthand for the end of the “peace and love generation.” Yet Tarantino’s slightly revisionist take suggests it’s not only the youthquake that died, but also a certain strain of Hollywood filmmaking that passed with it.

Although I don’t doubt their historical accuracy, the litany of titles that appear throughout Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels as curated as any of Tarantino’s music soundtracks. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, are films that entered the canon of great sixties cinema. Others, like The Night They Raided Minsky’s, are early films by directors who’d later achieve greatness. (In this case, William Friedkin, who won an Oscar in 1972 for The French Connection.)

But many, like Lady in Cement, Tora, Tora, Tora!, Krakatoa: East of Java, Mackenna’s Gold, C.C.& Company, and even The Wrecking Crew, are largely forgettable movies.

Tarantino clearly has affection for all of the drive-in theaters and Hollywood picture palaces where these titles played. But the titles themselves are evidence of the industry’s struggle to adapt to new tastes and a rapidly changing media landscape. Old-school show biz types, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, continued their success as singers and television personalities. But their careers as actors had functionally ended by 1969. And the efforts to keep them relevant often seemed either strikingly anachronistic or just plain weird.

In the opening scene of Lady in Cement, Frank Sinatra fights off a small school of sharks while he is examining the body of a nude woman who, like Luca Brazzi, sleeps with the fishes. And yes, the scene is as ludicrous as it sounds. If this is what became of Hollywood’s once great tradition, it is hard not to think we should just let it pass.

Yet, the fear of obsolescence also explains the oversize role that Tarantino gives to the Western as part of this changing landscape. True Grit and The Wild Bunch were among the summer of 1969’s biggest hits. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would eventually become the year’s top-grossing film. All three Westerns feature cowboy heroes that are either aging, outmoded, or both. They reminded contemporary viewers that horse riders would soon yield to horseless carriages, the lone bounty hunter would soon be supplanted by paramilitary detective agencies, and the humble six-shooter can’t match the lethal power of a Mexican army machine gun.

In retrospect, though, the popularity of the Western in 1969 represents the genre’s last gasp. Studios continued to make Westerns during the 1970s, but only three – Jeremiah Johnson, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and The Electric Horseman – would surpass $10 million in rentals in the entire decade.

On television, such long-running series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian had their last round-ups. The networks tried their hands at new Westerns, like Alias Smith and Jones (below), Hec Ramsey, Dirty Sally, and Lancer, but they were all short-lived. At the start of the 1980s, the genre was completely moribund. Subsequent efforts to recapture the Western’s former glory were mostly the equivalent of flogging a dead pony.

As a total cinephile, Tarantino is entirely aware of this aspect of the genre’s history. This is signaled quite explicitly in the decrepit condition of the Spahn Movie Ranch. Yet Tarantino also uses Rick’s career arc to signify its downward trajectory.

No character in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as strongly associated with the Western as Rick. His home is filled with collectibles like his Hopalong Cassidy coffee mugs. His walls are decorated with posters for The Golden Stallion and A Time for Killing. On set, he reads pulp oaters like Ride a Wild Bronc to relax between takes.

By using Rick to dramatize the twin declines of both Old Hollywood and its “bread and butter” genre, the narrative arc of Tarantino’s drugstore cowboy is one suffused with nostalgic melancholy. The key moment in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood occurs when Rick breaks down telling the story of Easy Breezy to Trudi Fraser, his Lancer co-star. He describes Easy “coming to terms with what it’s like to feel slightly more useless each day.”

The various threads of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s network finally knot together in the Manson family’s attack on Cielo Drive. At the moment of truth, it is telling that Rick reaches not for a firearm, but for the prop flamethrower he wielded in The 14 Fists of McCluskey. By recalling the moment when Rick shouts, “Anyone here order fried sauerkraut?”, Tarantino reminds us that violent spectacle and snappy quips will eventually replace the Western’s ritualistic showdowns.