Sunday | August 4, 2019

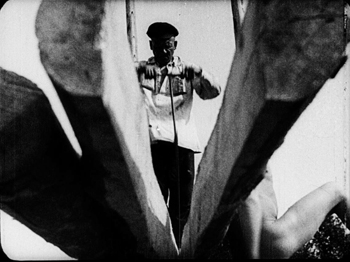

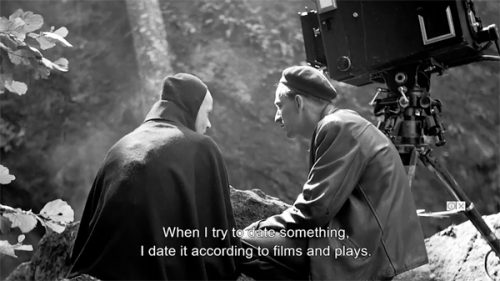

Fragment of an Empire (1928).

Kristin here:

Our friends at Flicker Alley have once again provided access to major works of silent cinema with two Blu-ray releases: Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Argent (1928) and Fridrikh Ermler’s Fragment of an Empire (1929).

Fragment of an Empire

When I was in graduate school, back in the 1970s, Ermler’s Fragment of an Empire (more accurately translated as “Remnant of an Empire”) was considered one of the major examples of Soviet Montage cinema. Its place in the canon seems to have faded since then, but this Blu-ray should restore its reputation.

Earlier prints of its were dicey. Its most famous scene was one in which the protagonist approaches a life-size crucifix at night on a battlefield and discovers that the head has been fitted with a gas-mask. David remembers seeing a print in which this image was present. I remember watching the film, expecting to see this image and being disappointed that it was not there. (I expected it because most histories of cinema that mentioned Fragment would use a production still of the crucifix.) Why the shots of the crucifix were removed is not clear, though presumably in countries where religious groups had some say in censorship matters, they were removed as blasphemous.

Peter Bagrov, formerly of the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and now Curator of the Moving Image Department at George Eastman Museum, was centrally involved in the film’s restoration and provides the essays in the accompanying booklet. According to him, nine prints of the film from archives around the world were examined for this restoration. Only two of them contained the gas-mask Christ shots, one of them being the Museum of Modern Art’s distribution print. David probably saw that. I saw another version; I don’t recall when or where. Bagrov suggests that some prints that circulated as the “canonical” version of the film were in fact an abridged, simplified version made at the time for circulation to the uneducated rural population. Now we can all see something very close to the full original 1929 copies.

The film’s title refers to Filimonov, who is initially suffering from amnesia and working as a hired hand for a peasant woman at a remote stop on a rail line. Seeing a woman on a passing train triggers his memory, and he realizes that she is his wife and that he was a non-commissioned officer during the World War I. Going home to St. Petersburg, now Leningrad, he is shocked by the modern architecture and short skirts, as well as the fact that the owner of the textile factory where he had worked is no longer the master there. He gets a job at the same factory. Who, he repeatedly asks his fellow workers, is the master?

Fragment of an Empire falls into the common Soviet plot pattern of following a character who at first resists or ignores the revolutionary changes in the USSR but comes to understand and support them by the end. It also falls into the “Rip Van Winkle” pattern of a character who, either through amnesia or some fantastical time warp, is thrown into a society that has moved ahead without him or her. It’s a convenient way of defamiliarizing, as the Russian Formalists would say, that new society.

The opening third or so of the film is its most impressive portion. Several early segments take place at night on the bleak, flat land around the train tracks. Ermler makes impressive use of the new arc searchlights that had been developed for surveillance during the war. These intensely bright lamps made shooting in exteriors at night practical for the first time. Ermler created stark, white strips of light against pitch black, picking out individuals from a great distance (see top). The effect at times resembles some of the abstract experimental shorts of the 1920s.

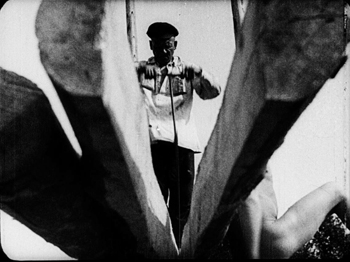

In the opening scene, the bodies of soldiers who have died of typhus are heaped on a train platform to be buried. The peasant woman orders Filimonov to strip them of their boots, but while doing so he finds one wounded soldier still barely alive and saves him. The second sequence has Filimonov spotting his wife and beginning to piece together his memories. Back at home, more reminders trigger a series of quick flashbacks: a sewing-machine’s crank leads to a machine-gun firing, a rolling spool recalls wheels of trains and tanks. A somewhat more extended flashback involves a tank advancing on a soldier as he prays and begs for help from the gas-mask-outfitted crucifix before being crushed–a traumatic scene presumably witnessed by Filimonov, though he is not shown. Through much of the extended recovery Ermler employs the extremely short shots, graphic conflict, and dynamic angles (below) typical of Soviet Montage filmmaking.

Perhaps inevitably, once Filimonov has fully regained his memory and gone to Leningrad, the film becomes more conventional. For a while he wanders about, simply staring and commenting in confusion and disbelief at the modern buildings and people he sees. His hiring at the factory and misunderstanding about who is master there generates some humor as the other workers tease him–in a comradely way, of course. As they explain the new egalitarian society to him, Ermler launches the longest and most varied “work is glorious” montage sequence I have ever seen in a Soviet film of the era, with joyous workers wielding everything from saws to microscopes and, yes, movie cameras.

There is also a brief but amusing scene in which Filimonov takes his old tzarist war medal to donate it to a collection of theatrical props. The bizarre objects in this little warehouse recall the decadent ones Eisenstein uses to characterize the tsar’s quarters in the previous year’s October. This scene, along with much of the motif of Filimonov’s medal, was also eliminated from the “village” version. The intertitles restored in Russian with the original graphic layouts of the original, so that when Filimonov’s repeatedly cries “Who?” when he asks who the master of the factory is, the word changes size and position on the black background from title to title. (There are English subtitles throughout.)

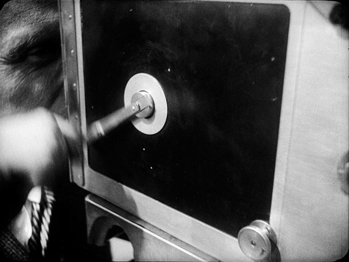

One praiseworthy decision made by the restorers was to leave in the lines of the splices.

These splice-lines are of use to the historian and analyst. Watching a 35mm print on an editing machine, one can examine these directly on the filmstrip. The temptation to “clean up” the images to look pure and attractive, however, too often leads to their elimination. They are part of the original film and should always be left as is.

The Flicker Alley disc is NTSC but without region coding.

L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier, though not one of my favorite directors, even of the silent period, was a major French director and has appeared on this blog a number of times. I included films by him in my annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago: El Dorado for 1921 and L’Argent itself for 1928. Flicker Alley has been particularly kind to L’Herbier, and I have discussed their releases of his L’Inhumaine and Feu Mathias Pascal. Having summarized the importance and style of L’Argent in the 1928 post, I’ll concentrate here on the restorations and supplements of the existing discs.

This is the third restoration of L’Argent. The original negative and a finegrain positive made from it survive. In 1971 a restoration was done from this material, but someone made the unwise decision to step-print the new version to simulate the 16 frames-per-second shooting/projection speed of silent cinema. In fact, by the early 1920s the speed of the majority of films was up to around 20 fps, and by the late 1920s, it had reached nearly the same as sound films, around 24 fps. The resulting print of L’Argent, already quite a long film for its day, was off-putting indeed.

A 1994 restoration removed the step-printing and produced a version of excellent visual quality; it provided the basis for the “Masters of Cinema” two-disc DVD set from British company Eureka!, released in 2008. My discussion of L’Argent in the ten best of 1928 included frames from that version, which is no longer in print. It has not been released in a Blu-ray edition.

The third restoration, done by Lobster Films in 2018, forms the basis for the new Flicker Alley Blu-ray disc. (The ongoing cooperation between the two companies has made possible many of Flicker Alley’s discs of splendid copies of hitherto rare or inaccessible silent films.) The original camera negative was scanned in 4K for this new version.

Those who do not own the Eureka! set should welcome the renewed availability of this major film, perhaps L’Herbier’s finest.

Although there is some overlap between the supplements on these two releases, there are also significant differences. Both Eureka! and Flicker Alley include include a 40-minute documentary, Jean Dréville’s Autour de L’Argent (“About L’Argent,” 1928), an elaborate early “making-of” docmentary. Eureka! also offered a 54-minute 2007 documentary, Marcel L’Herbier: Poet of the silent cinema, not in the Flicker Alley release.

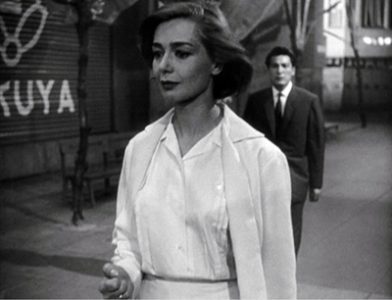

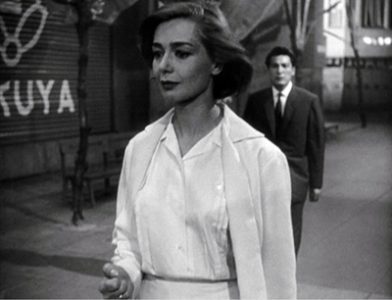

Flicker Alley, however, has two items not in the earlier Eureka! set. One is a five-minute short in which Serge Bromberg discusses “The Two Restorations of Auteur de L’Argent“, the Dréville documentary. More importantly, the other is a previously unavailable film, Prometheus Banker (Prométhée banquier). L’Herbier made this 16-minute short in 1921, apparently based very loosely on Zola’s novel, L’Argent. In retrospect, it looks like a brief sketch for the feature-length L’Argent, though it works as a one-reeler. It features L’Herbier’s familiar actors of the early 1920s: Eve Francis as the banker’s lover who longs to return to her happier, humbler beginnings (see below), Jacqe Catelain as the banker’s secretary, and Marcelle Pradot as the jealous typist. Apart from being an interesting early Impressionist film in itself, it provides a useful contrast in styles between similar stories told in 1921 and 1928 by the same director.

Neither the Eureka! release nor the Flicker Alley one has a commentary track. The Eureka! booklet is 78 pages long, with a lengthy essay by Richard Abel and a 1968 interview with L’Herbier, as well as some 1929 reviews of L’Argent. The Flicker Alley booklet is 23 pages, with essays by Mirielle Beaulieu.

According to the box and the film’s webpage, L’Argent is A/B/C, i.e., all regions (though the disc itself is marked A). It is presumably NTSC.

Many blog entries have discussed the Soviet Montage style; see this category. For more on French Impressionist cinema, see Scorsese, ‘pressionist and An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film. We provide background on the two movements in Chapters 4 and 6 of Film History: An Introduction.

September 1, 2020: The Fragment of an Empire release has won The Peter von Bagh Award at the 2020 Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Publishing Awards.

Prométhée banquier (1921)

Posted in DVDs, Film comments, National cinemas: France, National cinemas: Russia and USSR, Silent film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Two more classics from Flicker Alley open printable version

| Comments Off on Two more classics from Flicker Alley

Monday | July 29, 2019

DB here:

The Criterion Channel has just posted the latest in our Observations on Film Art series. In this installment I try to analyze Vagabond‘s shrewd and unsettling use of some traditional plot patterns: the road movie, the mystery investigation, and the network narrative. I argue that the orchestration of these patterns encourages us to think about our life choices.

You can watch the film here, and watch the video essay here.

Vagabond is a film I’ve admired since it came out in 1985, and by now it’s something of a classic. Its the original title, Sans toit ni loi (roughly, “Homeless and Lawless”) follows Varda’s habit of rhyming or punning titles: L’Opéra-mouffe, Daguerreotypes, Mur murs , Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Visages et villages. The mixture of playfulness and serious themes (homelessness, women’s rights, the struggles of the poor, the importance of ordinary people) makes her work unique. She respects both the problems of our lives and the possibility of finding something to affirm–if only our efforts to help one another. I was reminded of all these qualities by her last film, Varda par Agnès; seeing Vagabond again reminds me how much we miss her.

Several of our entries have been devoted to Varda; see the set here. In my view, Vagabond is her masterpiece, but she’s made many fine films, and a lot of them are available for streaming from Criterion.

Our entire Observations series is here. Thanks as ever to the Criterion team, especially Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and John Magary, who did a bang-up editing job. Thanks as well to Erik Gunneson here at UW–Madison. And thanks to colleague Kelley Conway for help with my scenario for this installment.

I discuss Vagabond as an example of ambivalent narration in the Afterword to “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 166-169.

Vagabond (1985).

Posted in Criterion Channel, Directors: Varda, Narrative strategies |  open printable version

| Comments Off on The Mona mysteries: Varda’s VAGABOND on the Criterion Channel open printable version

| Comments Off on The Mona mysteries: Varda’s VAGABOND on the Criterion Channel

Saturday | July 27, 2019

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries cite Film Art, but most of them are relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Readers who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we have posted well over 900 entries, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Last year for the first time I included recommendations for potentially useful videos in our series “Observations on Film Art” (a sort of extension of this blog) on the FilmStruck streaming service. Every month Jeff Smith (also our collaborator on Film Art), David, and I had contributed a visual essay that applied concepts from Film Art: An Introduction to a film (or films) streaming on FilmStruck, which began in November of 2016 and ended in November of 2018.

Fortunately in April, 2019, that platform was replaced by The Criterion Channel, which had been a major attraction as part of FilmStruck. The essays that we had contributed to FilmStruck have all been reposted on the new service, and we have continued to contribute monthly essays. As of now there are 29 essays online. See last year’s “Is there a blog in this class? 2018” for the earlier videos. (For information on the changeover of services, see here.)

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

I’ve written an occasional series on the progress of 3D in modern cinema. In an entry concentrating on exhibition rather than the technology or the movies, I talk about the decline in the number of 3D screenings as they lose popularity: “3D in 2019: RealDivided?”

In Chapter 1 we briefly deal with the concept of the author or auteur of a film. David provides an example of how one characterizes an auteur’s work in “Terence Davies: sunset songs.” Is Michael Curtiz as clearly an auteur as Orson Welles is? This entry considers some evidence.

No year on the blog is complete, it seems, without something on Hitchcock. This time David considered Notorious, preparing the way for a video essay for the Criterion release of this masterpiece.

At greater length, our updated e-book on Christopher Nolan is a study of him as an auteur with a “formal project.” David discusses the changes in “Christopher Nolan: Back into the Labyrinth.” A later entry considers (unconvincing) critical attacks on Nolan’s work.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In The Criterion Channel video essay, #25, “Lydia and the power of flashbacks,” David discusses the somewhat experimental ways in which flashbacks are used in Julien Duvivier’s 1941 romance. He extends his analysis in “Lovelorn LYDIA: A new installment on The Criterion Channel.”

I analyze one aspect of narrative form in The Favourite: “Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE.”

Narrative options both old (the 1940s) and new (Happy Death Day 2U) are considered in an entry on how incidents can be repeated and varied, within a film and from film to film.

This chapter of Film Art discusses narration in terms of depth, how much of characters’ knowledge and thoughts are revealed to us. In “Observations on Film Art” #26 on The Criterion Channel, Jeff examines technique that allow us access to the protagonist’s mind in “Memories of Underdevelopment.” He expands on that analysis in “Politics and Subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on The Criterion Channel.”

Can the tools of narrative analysis shed light on The Narrative of contemporary US politics? David tries in the entry “Reliable narrators? Telling tales on Trump.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

#27 in our “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel, David examines the intricate mise-en-scene of Kenji Mizoguchi: “Games of Vision in STREET OF SHAME.” He elaborates on the blog with “How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on The Criterion Channel.”

David analyzes the staging of a scene in Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Voto (The Mask and the Face, 1919) in “Sometimes an actor’s back …” Those of you teaching Film History: An Introduction might find this entry useful in relation to the discussion of tableau staging in Chapter 2.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinemagraphy

In The Criterion Channel’s #24 in the “Observations on Film Art” series, Jeff Smith analyzes “Widescreen Composition in Shoot the Piano Player.” He offers additional commentary on the subject in a blog entry, “On The Criterion Channel: Jeff Smith on SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER.”

Chapter 6 The Relationship of Shot to Shot: Editing

In The Criterion Channel’s #23 video, “Mutations of Memory–Editing in Hiroshima Mon Amour,” David discusses the film’s complex, innovative use of editing to create flashbacks. He expands on that analysis in the blog entry, “On The Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters.”

Dissolves provide a way to join shot to shot. They’re usually used sparingly and in conventional ways (flashbacks, ellipses). In “Observations on Film Art” #22 on The Criterion Channel, “Dissolves in The Long Days Closes,” I discuss how dissolves become a prominent formal device in Terence Davies’ film.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Guest blogger Jeff Smith analyzes the music in True Stories: “From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES.”

Jeff takes an informative look at the five songs from 2018 films nominated for Oscars in “Oscar’s siren song: The return: a guest post by Jeff Smith.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes cutting and framing in one scene in the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs in “The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master-class.”

The great critic André Bazin decisively shaped our sense of how to understand film form and style. David explores some of his ideas in “André Bazin, man of the cinema” and an essay, “Lessons with Bazin.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David on film noir: “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: much ado about noir things.”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

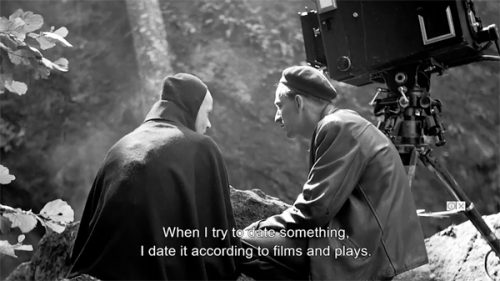

Reporting from the Vancouver festival, David discusses two documentaries that might be useful to show if you program films by either of these directors for your class: The Eyes of Orson Welles and Bergman: A Year in the Life. See his “Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors.”

David on three documentaries shown at our hometown film festival this year, in “Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas but docus as dramas.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We were lucky enough to return to the Venice International Film Festival last year, again offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premiere of Damien Chazelle’s First Man and is based on a single viewing. The second discussed Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Mike Leigh’s Peterloo.The third offered David’s thoughts on the posthumous release version of Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind. In a fourth, I dealt with five films from the Middle East, including Amos Gitai’s A Tramway in Jerusalem. David considers variants of wrong-doing in films from around the world, including Zhang Yimou’s Shadow and Erroll Morris’ American Dharma. Sixth and last was my longer analysis of László Nemes’s brilliant but challenging second feature, Sunset. We plan to carry on this tradition of comments on new films when we attend the Venice International Film Festival next month.

Our annual visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival yielded more brief analyses of new films. In “Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined,” David looks at some recent Asian films, including Kore-edge Hirozaku’s Shoplifters. In “Vancouver 2018: A panorama of the rest of the world,” I comment on three films by important international directors: Nuri Bilge Ceylon’s Turkish The Wild Pear Tree, Benedikt Erlingsson’s Icelandic Woman at War, and Pavel Pavlikowski’s Polish Cold War.

I followed up with more international films in “Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the rest of the world, the sequel“: Matteo Garrone’s Italian Dogman, Nina Paley’s American Sedar-Masochism, Wolfgang Fischer’s Austrian Styx, and Christian Petzold’s German Transit. David wrote about crime films (and a TV show) in “Vancouver 2018: Crime waves.” These notably included Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Our wrap-up, “Vancouver 2018: A few final films,” again had an international flavor, commenting on Jafar Panahi’s Iranian 3 Faces (his defiant fourth feature since the government banned him from filmmaking for twenty years), Nadine Labaki’s Lebanese Capernaum, and Ciro Guerra and Cristina Gallego’s Colombian Birds of Passage.

Looking back on these two festivals makes it clear that 2018 was an extraordinary year for the cinema!

David analyzes True Stories on the occasion of its release on Blu-ray: “Pockets of Utopia: TRUE STORIES.”

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

Teaching film history? My annual choice of the ten best films from 90 years ago offers some familiar and not-so-familiar titles: “The ten best films of … 1928.” I also consider two releases of major German silent films.

Many of our entries from Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna consider older films, especially those from 1919 in “German and Scandinavian classics.” I discuss some major African films in “Who put the pan in Pan-African cinema?”

I discussed a Blu-ray release of two rare films by Mary Pickford in “Pickford times two.”

A more recent trend in film history, that of the improvised independent American film, is considered in our review of J. J. Murphy’s book Rewriting Indie Cinema.

Finally, for Film Art: An Introduction users, an account of how Jeff Smith, David, and I revised our textbook for its twelfth edition.

After forty years, we’re still grateful to teachers and students who have found Film Art: An Introduction useful in their study of cinema.

Posted in FILM ART (the book), Film comments, Film history, Narrative strategies, Poetics of cinema, Silent film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Is there a blog in this class? 2019 open printable version

| Comments Off on Is there a blog in this class? 2019

Thursday | July 18, 2019

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

…can crisply punctuate a scene.

DB here:

One of the 1919 films on display at Cinema Ritrovato this year was Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Volto (The Mask and the Face, 1919). It’s drawn from a popular play that satirized the erotic stratagems of the elite. The movie begins by introducing a gaggle of couples at a Lake Como house party, so I expected that it would create interlocking intrigues in the manner of silent-era Lubitsch films like The Marriage Circle (1924). Not so: the plot concentrates on one romantic triangle. The version we have, at 1799 meters, might be a little shorter than the original (said to be around 1900 meters), but it seems likely that the plot we have dominated the initial release too.

Savina is betraying her husband Paolo with the family lawyer Luciano. During the house party Paolo declares that a cuckolded husband has every right to murder the unfaithful wife. When he learns of Savina’s affair (but not Luciano’s complicity), he orders her to leave the household immediately. Paolo declares that she will become dead to him and their friends.

Paolo tells Luciano that he killed Savina. We get a lying flashback (yep, already and again) that shows him strangling her and dumping her body in the lake. Savina overhears his false confession. When she hears Luciano asserts that she got what she deserved, she realizes he’s worthless. Disillusioned about both of the men in her life, she follows Paolo’s order and leaves their estate.

Of course a woman’s corpse, face mutilated, is soon found in the lake. Now Paolo must stand trial for Savina’s murder, and Luciano must defend him.

Not the funniest comedy I ever saw, but it has a grim charm. One particular scene made me happy.

Piano ensemble

Readers of this blog know that I like to study staging in 1910s films, and Genina provided nifty examples in the 2017 Ritrovato season. Like the Lupu Pick film I reviewed at this year’s jamboree, Il Maschera lies stylistically midway between pure tableau cinema and editing-driven construction. Interior scenes are often broken up by many cuts, but they’re typically axial, straight-in and straight-back, without reverse angles. (The exception is the trial scene. As in many 1910s films, it creates a more immersive space through “all-over” cutting.) In most scenes, the shots enlarge actors to follow their responses, but we don’t get setups that penetrate the space, putting us inside the flow of action.

Still, axial cuts, as Eisenstein and Kurosawa and John McTiernan knew, have a peculiar power. They can be abrupt and punchy, or more subtle in readjusting the framings. The latter option is on display in the film’s first big scene, when all the guests gather in the salon around the piano.

The scene runs about two and half minutes and consists of twelve shots and six dialogue titles. What’s worth noticing is the slight variations in setups, coordinated with what Charles Barr has felicitously called “gradation of emphasis.” Often the changing setups are masked by an inserted dialogue title, so there are no bumps in continuity.

The orienting view is a bustling shot that piles up faces and shoulders along the horizontal axis.

In an axial cut-in, the guests debate the righteousness of Othello’s murder of Desdemona. A further cut-in shows Luciano and Savina on the far right sharing glances. (The curly-haired woman will prove an innocent witness.) It’s a Hitchcockian situation, but without the POV singles.

Soon an older husband rises from his chair in the rear (another cut-in, “through” the group) and comes forward to join them. He draws alongside the husband to calm him down.

I’ve talked about crowded tableaus like this before. The Americans I survey were somewhat bolder than Genina in jamming the heads even closer together, creating partial faces that float out of the background. Genina has, however, other goals in view.

The woman in white

During the cut-ins, Genina takes the opportunity to rearrange the actors around the piano and re-scale his shots. There are five distinct variants of the piano grouping; even setups that might seem the same aren’t quite. There are two setups of the adulterous couple. All these are calibrated to suit the action presented.

For instance, when Paolo launches his rant about unfaithful women, the framing is tighter to favor him, and the foreground woman in white is primed for her big moment.

Similarly, the second cut to the adulterous couple is framed somewhat differently from the earlier one (on left), with Luciano pushing aside the cute curlyhead. He and Savina are listening more intently to Paolo’s denunciation of faithless wives.

So what seem to be fairly straightforward repetitions of setups are in fact minutely adjusted to favor certain actions. This strategy allows Genina to return to the whole ensemble.

In a closer view, the woman in white suggests that they stop arguing about infidelity and go in to play cards. She rises, blotting out Paolo in mid-rant.

The effect would be less pointed if she were in black like the other women.

Everyone but the older husband turns away, and people retire to the next room in the distance. They drain the space like water emptying out of a tub. That leaves what filmmakers today would call the scene’s button: the old man noticing that Luciano and Savina don’t join the group. Throughout the scene they’ve been literally marginalized on the far right.

It’s through this older man we just barely see the couple leave. He seems to understand the game they’re playing. and now he watches them disappear, perhaps to a private rendezvous.

The scene ends with another turning from the camera, another actor’s back letting us know the action is done.

Very often, turning from the camera signals the end of scenes, and of films.

It would have been fairly easy for any director to simply let the actors clustered around Paolo drag him off to play cards. But by having the woman in the foreground pop up, cut off our view of Paolo, and trigger a general exit Genina makes the action taper off briskly. Staging in the silent cinema is full of such little felicities, and it’s one job of criticism to appreciate them. It’s especially important since such techniques seem no longer part of filmmakers’ skill sets.

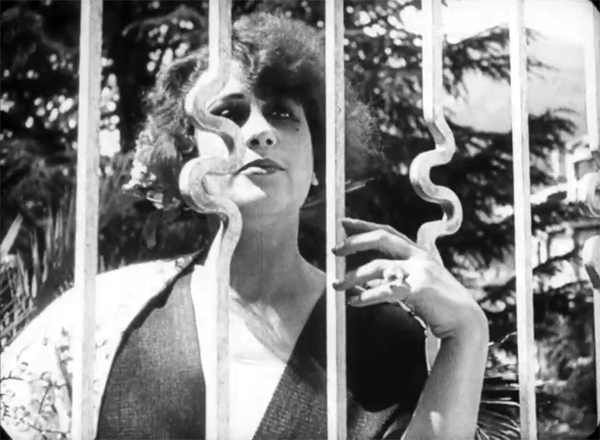

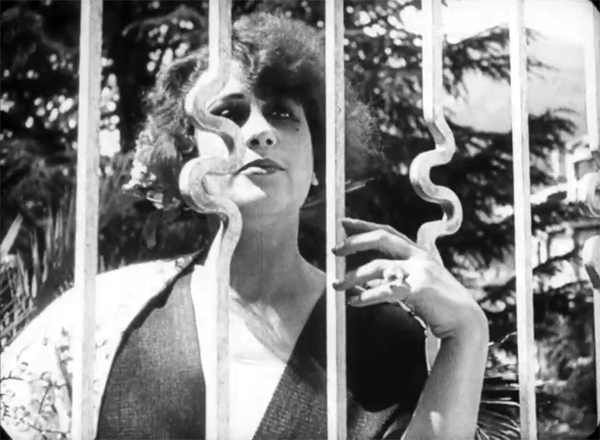

Then again, some Maschera images just whack you in the eye. Who doesn’t sense passion, elaborately caged, in the image below?

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. We particularly owe Mariann for her curating of the Hundred Years Ago series every year. Special thanks as well to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

Information about La maschera e il volto can be found in Vittorio Martinelli’s Il Cinema Muto Italiano: I film del dopogerra/1919 (Rome: Bianco et nero, 1960), 170-172.

Other Sometimes... entries consider a single axial cut, a shot in depth, a jump cut, a reframing, and a production still.

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

Posted in 1910s cinema, National cinemas: Italy, Silent film, Sometimes . . ., Tableau staging |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Sometimes an actor’s back… open printable version

| Comments Off on Sometimes an actor’s back…

|