Sunday | July 7, 2019

Muna Moto (1975)

Kristin here–

With the plethora of films on offer this year at the XXXIII edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I decided that a necessary strategy for choosing those to watch would be to follow certain threads faithfully and then fill in the remaining time-slots with bits and pieces from other threads. (The entire program, with notes, is online here.)

A program that formed part of the core of my viewing for the festival’s eight and a half days was “Cinemalibero. FESPACO 1969-2019.” It was curated by Cecilia Cenciarelli, whose program notes explain the post-colonial context behind this fiftieth-anniversary celebration:.

“Decolonisation of the screen” also spread at a grassroots level: birthplace of the future FESPACO, the film club of the Centre Culturel Franco-Voltaïque in Ouagadougou (capital of the then Republic of Upper Volta) organised the first Semaine du cinéma africain in February of 1969. Cinema filled every venue of the city: the Nadar and Olympia cinemas, schools, offices, the People’s House and Hôtel Indépendance, the legendary filmmakers’ headquarters. Over 50 films made in Senegal, Niger, Upper Volta, Cameroon and Benin by directors like Sembène, Samb, Traoré, Alassane and Sita-Bella were screened.

The first festival in 1969 has been credited with bringing together filmmakers from all over the continent to launch an effort to support Pan African filmmaking. Short documentaries showing FESPACO in its early years, mostly by Tunisian filmmaker Mohamed Challouf, were shown before several of the features.

The program was built around eleven films directed by pioneers of the festival and the Pan African Cinema effort in general. Of those, eight were recent restorations–some of them dated 2019. Some of these films have been available online in copies with poor visual quality, and I hope now the new prints will make their way onto Blu-ray or DVD. (Ousmane Sembene, the African filmmaker best known in the West, was not represented in the program, but he was instrumental in the founding of FESPACO.)

A key problem in restoring and distributing these classic African films is the fact that many of them had to be processed in European laboratories, often in France, and the original negatives and other elements were stored there. In some cases their whereabouts are now unknown, and tracking them down has been a key factor in making them accessible again.

Here is a brief description of each film, in the order in which they were shown. In keeping with the theme of Pan African cinema, every film originated in a different country.

De quelques événements sans signification (1974, Morocco)

As the program demonstrated, the mid-1970s were a key period for the establishment of Pan African cinema. Many show the influence of European filmmaking, since several African filmmakers studied filmmaking abroad.

Mostafa Derkaoui’s 1974 film shows the influence of Godard. Its early section consists of an extended scene in a bar, where telephoto shots move across a group of filmmakers debating what direction the establishment of Moroccan cinema should take. They take to the streets to explore the situation of workers.

When one of them kills his boss, the plot takes shape as the filmmakers focus on his situation as the subject of their film. Ultimately the worker rejects their interpretation of his crime, leaving the question of how Moroccan cinema should proceed up in the air.

Les bicots-négres, vos voisins (1974, Mauritania)

Two years ago, Med Hondo presented his West Indies (1979) at Il Cinema Ritrovato. It was my introduction to his work. As I reported at the time, Hondo was thoroughly ingratiating and was moved to tears by the enthusiastic applause we gave his film. This year the two diretors who attended, Jean-Pierre Kinongué-Pipa and Souleymane Cissé, were similarly touched by their reception. It is a pity that such recognition has been so long in coming. Hondo’s death in March of this year and Moustapha Alassane’s in 2015 perhaps deprived us of other guests who might have realized that their films will live on as classics.

Hondo’s Les bicots-négres, vos voisins (roughly, “The Arab-niggers, your neighbors”), also shows a strong influence of Godard’s political films of the 1970s, and yet it is thoroughly original as well. The film breaks into seven separate sequences–all politically didactic and yet greatly varied in their approaches. The results is continually riveting.

Aboubakar Sanogo’s program notes describe this variety:

It comprises seven sequences exploring, respectively, the conditions of possibility of cinematic representation in Africa (the opening sequence), historical dissonance through the dialectic of past and present (the post-credit sequence), a flashback to the eve of African independence (the imaginary garden party sequence), the predicaments of the post-colony, an assessment of the living condition of migrant workers and the actions taken to transform these conditions, and a final sequence in a circular mode, which returns to the new cinema.

Thanks in part to these recent restorations, Hondo has emerged as one of the giants of Pan African cinema.

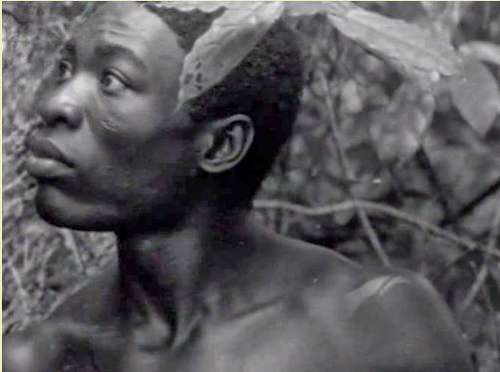

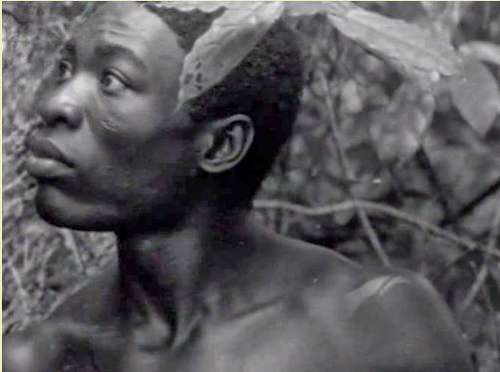

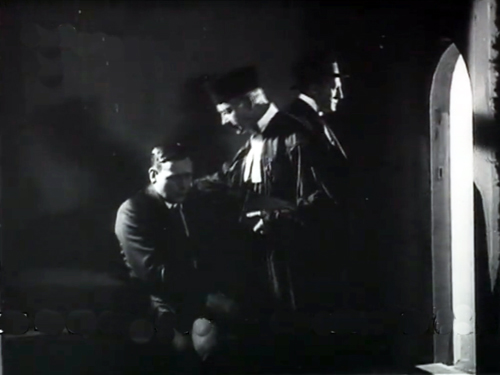

Muna Moto (1975, Cameroun)

Jean-Pierre Dikongué-Pipa was present to introduce this, one of the first films made in Cameroun. Though hampered by budgetary and censorship constraints, Muna Moto is an affecting story attacking both polygamy and the dowry tradition. The basic premise is that for any man in this culture, fathering a child is of prime importance, more than his love for any of his wives.

The protagonist N’gando, a poor, hard-working young man (see top image), aspires to marry N’Domé, a woman who genuinely loves him. The high dowry necessary to arrange such a marriage, however, presents a nearly insuperable barrier. While N’gando struggles to raise the money through low-paying manual labor, his rival, the wealthy M’bongo, who already has three wives who have failed to give him a child, takes the woman as a fourth wife in the hope of conceiving a baby.

She is already pregnant by N’gando, however. (The title translates as “Another’s Child.”) The film becomes a struggle in which N’gando tries to kidnap the baby girl.

The scene of the kidnapping opens the film, without explanation. Only gradually through flashbacks do we come to understand his motives and the tragedy of the situation. Muna Moto effectively uses the flashback conventions of European art cinema (Dikongué-Pipa had studied at the Conservatoire indépendent du cinéma français in Paris) to tell a thoroughly indigenous story with beautiful black-and-white cinematography.

The Cineteca di Bologna’s L’Immagine Laboratory restored the film in 2019 with the support of The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. Ideally this will make the film widely available on home video and for viewing at festivals.

Le retour d’un aventurier (1966, Niger), Samba le grand (1977, Niger), and Kokoa (2001, Niger)

Moustapha Alassane directed about two dozen films, mostly shorts. He is credited with being one of the few major African directors who was completely self-taught in filmmaking. Three of his shorts were shown in one program. Le retour d’un aventurier suggests how foreign cultures adversely affect regions of Africa. A popular young man from a village returns from a trip abroad, presenting his friends with six-shooters and cowboy outfits.

At first these would-be cowpokes seem ludicrously out of place, and yet when they begin to terrorize their peaceful village, their violence becomes all too familiar.

Alassane was a pioneer of African animation. His Samba le grand, the first color animated film made in Africa, combines hand drawings and simple cloth dolls to tell a traditional African folk tale effectively.

The most engaging of the three films on the program was Kokoa, a more elaborate and sophisticated cartoon. Using puppet animation, Alassane presents a traditional Niger-style wrestling match among frogs and lizards, with a sideways-moving crab hilariously mimicking the typical movements of a referee (above).

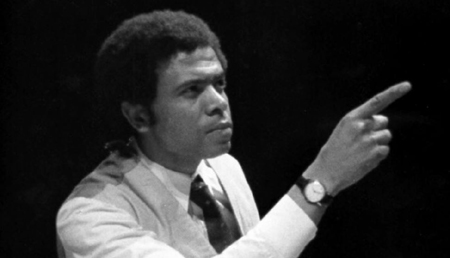

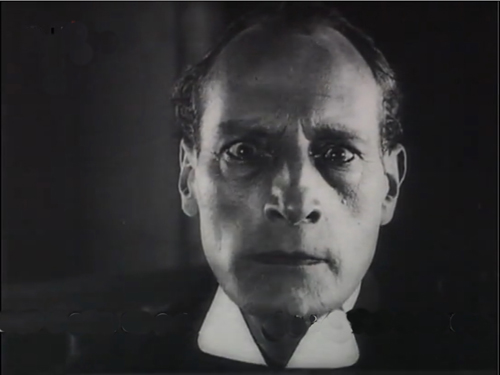

Baara (1978, Mali)

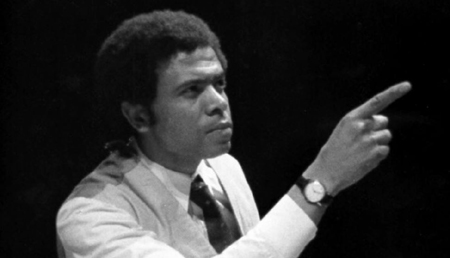

One of the most revered African directors, and certainly so among those living, is Souleymane Cissé.

Cissé was present for a Q&A session after the film. He was forthright in declaring that the somewhat faded print shown was too pink and that he would rather have had it destroyed than shown publicly. Cenciarelli assured him and us that it was the best 35mm print available, and audience members declared themselves delighted to see the film even in a less than ideal copy. Cissé stuck by his opinion and pointed out that the original negative survives intact in Paris. Ideally a restoration comparable to the ones shown in this series will someday be done.

He also mentioned that although he was jailed for accepting French funding for his first feature, Den Muso (“The Girl,” 1975), he still does not know the real reason for his arrest. He wrote the screenplay for Baara (Work) while in jail.

The film tackles the issue of the rise of a working-class in a country that had been largely rural and agriculturally based. The central figure is an uneducated young peasant who comes to the city and works as a porter. His cousin, educated and westernized, attempts to help him but is himself oppressed by the corrupt company officials above him. (Both are seen in the image above.) Unlike many other African directors who went abroad to study filmmaking, Cissé attended VGIK in Moscow (as did Sembene). Possibly the experience accounts for the narrative’s distinctly Marxist tone.

For more on Baara, see Richard Brody’s review on the occasion of a recent screening of the film at the New York African Film Festival.

La petite vendeuse de Soleil (1999, Senegal) and Le franc (1994, Senegal-Switzerland-France)

Earlier this year I reported on the showing of a restored print of Djibril Diop Mambéty’s, Hyenas (1992), at the Wisconsin Film Festival. After Touki Bouki (1973), it was the second of two full-length features Mambéty made before his early death at the age of 53. He followed Hyenas with the two short features (45 minutes each) from an intended trilogy entitled Contes des Petites Gens. The pair were shown together at the festival.

La petite vendeuse de Soleil (The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun) is perhaps Mambéty’s greatest film, though it is difficult to be objective given the utter charm of its central character, along with the performance of Lissa Balera in the role of Sili. Looking past that, though, the film is beautifully shot in locations in and around Dakar, and the narrative unrolls with a calm surety that packs a great deal into a short length.

Mambéty establishes the initial setting in the outskirts of Dakar in a leisurely fashion with dawn shots of the poverty-stricken area. We glimpse Sili limping past the hovels of the suburban slum, though we see other marginal figures as well–including a man pounding large pieces of stone into gravel. The planes taking off and landing behind him establish the theme of poverty juxtaposed with the modern, wealthy society of the city.

Soon we become attached to Sili as a friend takes her into the city to beg. She notices boys making money selling newspapers and soon becomes the first female to become a newspaper seller. Through a fluke of good luck, a wealthy man who sees her as a sign of African progress gives her a large bill to buy all her papers. Immediately confronted by a policeman over the large bill, she defiantly leads the way to the police station and talks the chief into releasing her and a woman charged with theft without reason. Once freed, she celebrates her good fortune by leading a cheerful dance in the street (above) and treating her friends to sodas.

She buys her blind grandmother a large umbrella to shade her as she sings for a living, and she gives small coins to her fellow beggars. Her generosity endears her to a seller of the rival newspaper, who becomes her defender. Her cheerful resilience persists despite bullying by a gang of rival newspaper sellers.

The film combines a realistic view of the grim life of street people in Dakar with a vision of hope represented by Sili. At the end, Dembéty dedicates it to the city’s street children.

Le petite vendeuse de Soleil was restored in 2019. Ideally, the currently available prints, with their somewhat soft images, will be replaced with this impressive version.

The second film in the series, Le franc, is not as engaging. It centers around Marigo, a shiftless man who is beleaguered by his landlady for back rent on his simple shack. He purchases a lottery ticket and, to prevent its loss, glues it to the shack’s door. When the ticket wins, he carries the door to the lottery agency, only to be told that a number on the back of the ticket is essential to allow him to collect the money. The main action is mainly extended slapstick as Marigo clumsily carries the door, frequently falling or dropping it. It’s an entertaining film but lacks the depth of La petite vendeuse du Soleil.

La femme au couteau (1969, Ivory Coast)

Timité Bassori’s La femme au couteau (“The woman with a knife”) is the earliest of the feature films shown at this year’s festival. Like numerous other directors from the continent, Bassori studied at IDHEC in Paris. The influence of 1960s European art cinema seems stronger in this film than in the others in this program.

The story is entirely based around the psychological problems of a young, unnamed, westernized man, whose romance with an unnamed woman is hampered by his disturbing hallucinations of a woman threatening him with a knife. Deciding to avoid traditional African cures, he finally is committed to a mental institution. Ultimately he recalls the trauma that had triggered his psychological problems. The film is skillfully made, with Bassori memorable as the protagonist, but it seems the kind of story that could have been made in a European country as well as an African one.

The excellent print was a product of the African Film Heritage Project, a program within the The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project; it was restored at the Cineteca di Bologna in 2019.

Wend Kuuni (1982, Burkina Faso)

This classic film was restored in 2017 by the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique. In his introduction, archivist Nicola Mazzanti expressed bitterness that Wend Kuuni has been neglected by distributors and exhibitors for decades. This new print should give it the second life that it richly deserves.

As Mazzanti pointed out, this is one of the few African films that portrays the continent as it was before colonialists invaded and changed the local culture forever.

The film follows the story of a mute orphan who is discovered nearly dead and taken in by a local farmer. (The title translates as “God’s Gift” and is the name bestowed upon the boy by his adoptive father.) Rather than develop a straightforward drama of the boy’s character arc, director Gaston Kaboré (who collaborated in the restoration) creates what is nearly a documentary on traditional rural life. We see the young protagonist herding sheep, the women of the family grinding grain, and so forth. Any progression in the plot takes place at wide intervals. The orphan’s origins and the reason for his muteness remain lingering mysteries but are not much dwelt upon until late in the film, where flashbacks and a traumatic discovery restore his voice and reveal his past.

Probably coincidentally, these two films about trauma and recovery through the recognition of a disturbing event in the past were shown back to back. But while La femme au couteau calls upon modern notions of psychology, Wend Kuuni simply presents the boy’s muteness and eventually shows his recovery without any reference to psychological concepts.

I am happy to say that some of these African films featured in our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, from its earliest edition in 1994: Les Bicots-Négres, vos voisins; Muna moto; and Wend Kuuni. We also discussed other films by Cissé and Sembene. At the time, few of these films were available for screening. It is encouraging to see such films revived and disseminated more widely.

Baara (1978).

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

Posted in Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato, National cinemas: Africa |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019: Who put the Pan in Pan African cinema? open printable version

| Comments Off on Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019: Who put the Pan in Pan African cinema?

Saturday | June 29, 2019

DB here:

Hundreds of films, thousands of passholders, sweltering heat (105 degrees Fahrenheit on Thursday). Dazzling tributes to Fox films, Youssef Chahine, Eduardo De Filippo, Henry King, Felix Feist, silent star Musidora, sound star Jean Gabin, and other themes. Many filmmakers from Africa, South Korea, and Europe, as well as master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Yes, Cinema Ritrovato is on steroids this year.

And as we always say: There are so many tough, indeed impossible, choices. Kristin has been faithfully following the African series, while I’ve hopped between restored and rediscovered Hollywood classics and the films from 1919. Today I’ll report a bit on the latter, with an addendum on a major filmmaker’s ave atque vale.

1919 bounty

Song of the Scarlet Flower (1919). Production still.

By the end of the 1910s, the feature-length format had become well-established, and a bevy of directors in Europe and America were launching their careers. Abel Gance, Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller, John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Cecil B. DeMille, Lois Weber, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Mary Pickford, and many other figures had already made impressive work. 1919 brought us some outstanding titles. There was von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, Griffith’s Broken Blossoms and True Heart Susie, Lubitsch’s Madame DuBarry, along with the lesser-known Victory of Maurice Tourneur, the first part of Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar, and the overbearing, delirious Nerven of Robert Reinert.

Bologna showed none of these. Its massive 1919 lineup featured some classics in restorations, notably Capellani’s The Red Lantern (starring Nazimova), Dreyer’s debut The President, and Stiller’s Herr Arne’s Treasure. As a sidebar there was the 1919 Italian serial I Topi Grigi, a fun sub-Feuillade exercise in crooks and chases with some nifty shots. And there were a great many fragments and short films from that year, including a Hungarian entry by Mihály (Michael) Kertész (Curtiz).

Less known than Stiller’s official classics is The Song of the Scarlet Flower, a wonderful open-air drama about a young farmer’s wanderings and his heart-rending romances with three women. In a new digital version, it emerged as one of the most sheerly beautiful films I saw at Bologna. The central action sequence, in which the hero dares to ride a log through rapids to the very edge of a waterfall, gained even greater tension thanks to the swelling orchestral score by Armas Järnefelt–the only original score to be preserved for a Swedish silent.

1919, German style

Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp, 1919). Production still.

Then there were two remarkable German films unknown to me, both by directors better known for later work. Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp) was by Karl Grune, most famous for The Street (Die Strasse, 1923). The plot follows a shiftless young man who casually becomes a pimp and pulls women into prostitution. Introducing the film, Karl Wratschko pointed out that many Weimar films warned of sexual misbehavior, and certainly the young hero of this film gets ample punishment for his sins.

Stylistically, Der Mädchenhirt was typical of much European cinema of the late ‘teens, when the tableau style, which promoted intricate staging with few analytical cuts, was losing force. Grune mostly handles action in ensemble shots broken up by axial cuts to closer views. If German filmmakers weren’t quite as editing-prone as other European directors, that may be because they didn’t have access to American models. Not until January 1920 were Hollywood films of the war years imported into Germany.

Another film carried this moderate continuity style to an intriguing extreme. Tötet nicht mehr! (Kill No More!) framed a plea against capital punishment within a family drama. Sebald, the son of a by-the-book prosecutor, falls in love with the daughter of a former prisoner. When Sebald is cast out by his father, the couple take up a theatrical career playing Pierrot and Colombine. But then Sebald blocks the theatre director from seducing his wife, so the director blackballs them and they can’t get work in other shows. Visiting the director, Sebald quarrels with the man and kills him. He’s arrested, tried, and sentenced to death.

Tötet nicht mehr! displays some remarkable visual qualities. Cross-lighting in the climactic prison scenes sculpts Sebald, the priest, and the lawyer Landt in a bold variety of ways.

Director Lupu Pick (Sylvester, 1924) uses this dramatic lighting to enhance the tableau-plus-axial-cut approach. The police are examining the crime scene and questioning Sebald. A depth composition gives us the corpse in the lower foreground, the detectives in the middle ground, and way in the back, the barely-visible face of Sebald perched between the shoulders of the two central men.

One detective walks to the distant background to question Sebald. Anybody else would have staged this bit of action in the better-lit zone on the left, where a detective talks with his colleagues. Instead, far back, a single pencil-line of light picks out the edge of Sebald’s face and body.

An axial cut-in presents a tight two-shot of the cop and Sebald–again, made stark and tense by the lighting.

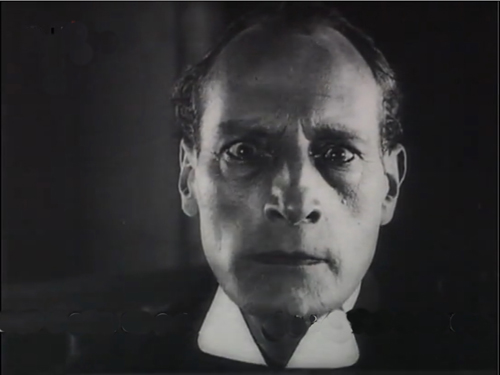

The plot of Tötet nicht mehr! is a generational one, starting with the tragedies befalling the woman’s father. These scenes introduce the sympathetic lawyer Landt, who tries to help the family throughout its troubles. Landt becomes the vehicle of the film’s message against capital punishment, which gets full airing in the boy’s trial.

In the films of the 1910s, courtroom scenes tend to be more heavily and freely edited than others. This is largely because of the need to cut among judges, jury, witnesses testifying, lawyers pontificating, and the onlookers. Pick exploits the situation with dozens of shots of participants. We also get optical point-of-view shots showing Sebald awaiting the jury’s verdict by staring at the doorknob of the jury room. There’s even a “lying flashback,” which dramatizes the prosecutor’s inaccurate reconstruction of the quarrel that led to the crime.

Most impressive, I think, is the pictorial progression in Landt’s impassioned plea to the jury to let Sebald escape execution. Among many reaction shots and reestablishing framings, Landt is rendered in increasingly close shots as he addresses the judges and the jury–and us.

The textural lighting and the ruthless elimination of the background reminded me of the trial scene of André Antoine’s Le Coupable of 1917, run at an earlier installment of Ritrovato.

There were plenty of other 1919 films on display, several of which I have yet to see. But this should give you an indication of the service that Cinema Ritrovato continues to render to the cause of understanding film history.

Not so long ago

The Widows of Noirmoutier (2006).

Film history close to our time was the subject of Varda par Agnès, the filmmaker’s last statement on her career. Prepared during her final years of life and produced by her daughter Rosalie Varda, it’s a poignant and revealing account of what mattered to her in her work. It showed Varda’s wry, playful humor and her commitment to treating social issues in intimate human terms. It’s a body of cinema that grows ever more important each year.

Varda par Agnès also showed her characteristic sensitivity to overall form. It’s framed by bits of her talking to audiences in master classes, so she becomes the narrator. Some stretches are chronological, going film by film, but just as often the links are associational. The women of Black Panthers (1968) remind her of the abortion activists of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977). That’s about the friendship of two women, which suggests by contrast a film about a woman alone, Vagabond (1985). The beach of Vagabond summons up the plenitude of Le Bonheur (1965). And so on.

This might seem rambling, but it’s not. Varda explains that she often conceives her films with a strict structure–the strung-together tracking shots of Vagabond, the tight time frame and spatial coordinates of Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). Varda par Agnès splits about halfway through, flashing back to Varda’s early still photography and adroitly linking that to her emergence as a “visual artist.”

She began mounting expositions like L’Îl et Elle, which housed cinema cabins (big transparent cubes made of ribbons of 35mm film) and Widows of Noirmoutier. Around a central image of collective grief, small screens show women sharing the everyday details of life without a partner. In just this clip, it’s almost unbearably touching. Apart from the resonance with Varda’s devotion to Jacques Demy, I was reminded of Chekhov’s line: “If you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t get married.”

We’ve been so busy with films, and queueing for films, that we’ve had little time to blog about our visit. Later entries will have to come after we’ve left Cinema Ritrovato.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Marianne Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

The complete score for Song of the Scarlet Flower is available on CD and streaming.

For Varda’s last visit to Cinema Ritrovato, go here. We discuss Varda’s career and Kelley Conway’s in-depth study of it here. See also Kelley on Varda at Cannes. A forthcoming installment of our Criterion Channel series is devoted to Vagabond.

For more on the stylistics of 1910s films, see the category Tableau Staging. I discuss The President in the Danish Film Institute essay, “The Dreyer Generation.”

The Criterion Collection’s magnificent Bergman collection wins Best Boxed Set at the annual DVD awards, Cinema Ritrovato 2019. Congratulations to producer Abbey Lustgarten and all her colleagues!

Posted in 1910s cinema, Directors: Varda, National cinemas: Germany, National cinemas: Sweden, Silent film, Tableau staging |  open printable version

| Comments Off on A hundred years ago, and less, at Cinema Ritrovato ’19 open printable version

| Comments Off on A hundred years ago, and less, at Cinema Ritrovato ’19

Friday | June 21, 2019

The Third Man (1949).

DB here:

En route to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, Kristin and I paid a visit to this wonderful city. We wandered around, stomped through museums, ate tasty food, and saw a bit of the city’s film culture.

Visiting venues

Our first stop was the Austrian Film Museum. Founded in 1964 by the avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka, the Museum has built up a collection of over 30,000 films. It contains a fine film theatre with features of the “Invisible Cinema” (above) that Kubelka and Jonas Mekas set up in Anthology Film Archive many years ago.

The Museum has been a pioneer in producing outstanding books and DVD editions devoted to an eclectic array of filmmakers (James Benning, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Straub/Huillet, Joe Dante). Exceptional as well are the Museum’s online offerings of films, clips, images, and paper documents.

Our host was our old friend, the ebullient curator Christoph Huber. Here he is with his colleagues Alexandra Thiele and Jurij Meden.

We didn’t have a chance to visit the classic Stadtkino in the same neighborhood, nor did we check out the highly esteemed Austrian Film Archive. But I did mosey down to the Gartenbaukino, a big, beautiful modernistic venue.

Built as a ballroom that occasionally screened films, the Gartenbau was made a permanent cinema in 1919. In 1960, after being redesigned by Robert Kotas, it opened as a showcase for widescreen motion pictures.

It’s now said to be the biggest theatre in Austria, with over 700 seats. Note the rising curtain, said to be a rarity these days.

The Gartenbaukino is equipped to project not only digital and 35mm but also 70mm. Managing Director Norman Shetler notes that it was the first Austrian theatre to boast large-format projection (for Spartacus) and was adapted for Cinerama as well.

More recently, the Gartenbau reactivated its 70mm equipment to show The Hateful Eight. The Phillips DP70 projectors now screen wide-gauge classics like Lawrence of Arabia and The Sound of Music. Picture and sound were excellent for The Dead Don’t Die, so I bet 70mm shows here are fantastic. Like the Stadtkino, the Austrian Film Archive, and the Film Museum, the Gartenbau is a venue for the city’s annual film festival, the Viennale.

Prater, not so violet

Plenty of movies have been set in Vienna, most notably The Joyless Street, Merry-Go-Round, Letter from an Unknown Women, and Amadeus. But for movie nerds the most flagrant example is The Third Man (1949). And Vienna hasn’t forgotten what this movie did for its local landscape, not least the amusement park set within the vast and beautiful park known as the Prater.

Said to be the oldest amusement park in the world, the Prater ‘s entertainment sector contains attractions that are shiny and enjoyable old-school rides: roller coaster, loop-the-loop, tilt-a-whirl, haunted house. There are shooting galleries, ice-cream stands, and even a Madame Tussaud’s.

But of course the looming attraction is the great Ferris wheel that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and Harry Lime (Orson Welles) share during their ominous reunion. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who always expects Harry to try to throw his old friend out of the cabin.

The big wheel has been declared a site of European film culture and decorated with a more or less accurate image of the coy Lime.

My ride in the wagon was gentle and elating. I tried to replicate Harry’s POV on the “ants” below, whose lives, he says, can’t matter much.

A studio-based version of the Prater featured in the now mostly lost Josef von Sternberg film, The Case of Lena Smith (1929).

Oh, yeah–we also paid a visit to a street named for one of my favorite auteurs. See below.

Next up: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

For information about Viennese film culture, thanks to Christoph Huber, his colleagues, and the indefatigable Ted Fendt. Thanks as well to Norman Shetler and two staff members at the Gartenbau cinema. Christoph, by the way, is an exceptional critic. You’ll learn from reading his essays in Cinema Scope.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Directors: Welles, Film archives, Film comments, Movie theatres |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Cine-Vienna open printable version

| Comments Off on Cine-Vienna

Tuesday | June 18, 2019

Lobby, Von-Melle-Park 9, Universität Hamburg, with Murray Smith.

DB here:

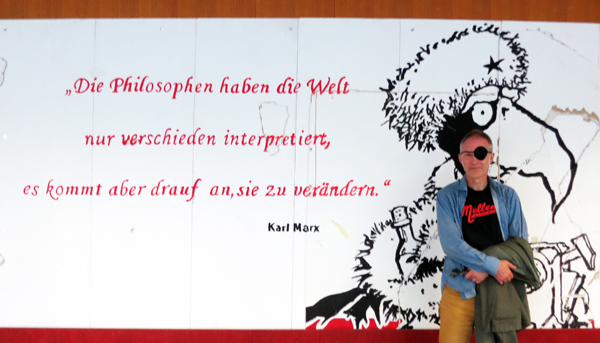

How many universities in the US would post a big quotation from Karl Marx in the lobby of a classroom building? (Answer: None.) But a cartoonish rendition of Marx’s killer app–the task of philosophy being not only to understand the world but also to change it–greeted the one hundred or so scholars attending the latest conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image last week at the Universität Hamburg.

How much we’ll change the world remains to be seen. What is clear now is that thanks to the superb organization of Kathrin Fahlenbach, Maike S. Reinerth, and their team, the SCSMI had a lively four days of papers, discussions, and excursions–as well as a screening of a strong film by a skillful director previously unknown to me. In all, every good reason to go to a conference.

Big questions, candidate answers

Carl Plantinga, Dirk Eitzen, and Kathrin Fahlenbach on the Hamburg Harbor cruise.

The range was huge, as usual, because this is a very diverse group. Our community, as I’ve mentioned in earlier reports, hosts film scholars, scholars of other media (television, games, internet), psychologists, and philosophers. Recurring questions include: How do viewers comprehend media presentations? What is the role of morality in film and television? How do practitioners conceive their craft? How do media present and trigger emotions? What appeals are specific to certain genres or historical periods? Not least: How may we construct good theories to answer such questions?

Three sessions ran simultaneously at each time slot, so I missed many good presentations. Kristin and I occasionally doubled up. Many of the talks will eventually become published papers, several in the Society’s journal Projections, so let me just highlight a few strands.

For those of us interested in how style interacts with narrative, there were several significant presentations. James Cutting, who has pioneered the use of Big Data techniques in scanning large batches of films, provided a compact account of how “sequences” (as opposed to scenes) displayed patterns of coherence and grouping. Karen Pearlman discussed her films, and James examined them to reveal fractal patterns in their rhythms–patterns that match the dynamics of footsteps, heartbeats, and breathing.

Two papers added to our understanding of the Kuleshov effect, much discussed on this site. Marta Calbi and her collaborators conducted EEG testing on spectators exposed to a Kuleshovian film scene, while Anna Kolesnikov, another member of the team, traced the contradictory versions of the “experiments” that Kuleshov and his students purportedly constructed. Both were exciting contributions to our understanding of Kuleshov’s legacy, which as the years go by looks more complex than we had thought.

Other papers on visual style included Barbara Flückiger’s tour of the staggering resource she and her colleagues have devoted to the history of color in film–a database of images from 400 films illustrating a range of technologies, periods, and genres. She has also mounted a magnificent array of tools for detailed analysis of color. (Significantly, she has taken the images from film prints, not video copies.) Here’s one of several stunning images she has taken from Helmut Käutner’s Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944, Agfa nitrate).

Stephen Prince, whose book Digital Cinema has just been published, surveyed the emergence of “deep fakes,” manipulated images that have no basis in reality but which are indiscernible from an accurate image. Steve was once skeptical that digital images would ever cut us off entirely from photographic reality, but now machine learning has managed to do it. Sped up by social media, the rise of unverifiable “records” creates what he called “an attack on an information system we call society.”

Hitchcock, everybody’s idea of a shrewd filmmaker (when will cognitivists discover Lang?), came in for his usual close treatment. Todd Berliner proposed five ways in which story information can be set up and paid off in a narrative, and he used Psycho as an instance of at least four of those methods. Maria Belodubrovskaya countered Hitchcock’s constant claim that he relied on suspense and not surprise. She showed that both single sequences and overall plots (e.g., Suspicion, Psycho) were heavily dependent on surprise effects.

In the first day, the range of the “humanistic” side of SCSMI was on vivid display. Malcolm Turvey asked whether the give and take of philosophers’ arguments converged on a consensus about truth, the way that much of science progresses. To illustrate the process, he considered the return of an “illusion” theory of images put forth by Robert Hopkins. Later that day, Jeff Smith used the cognitive theory of confirmation bias to show how characters in Spike Lee’s Clockers systematically misunderstand the story situation. The result, enhanced by genre conventions and a violation of some traditions of the detective story, enmeshes the viewer in the same error.

On the other end of the spectrum, there were papers mobilizing empirical research. Timothy Justus drew upon Lisa Feldman’s work in How Emotions Are Made to suggest that a biocultural account of facial expression should not rely too strongly on Paul Ekman’s classic argument about universal, basic expressions. More room, Justus proposed, should be given to cultural forces that build “emotion concepts” that filmmakers and viewers draw on.

A more hands-on empirical project was that coming from a team at Aarhus university. Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen posed the question: What if sympathy for a film’s villain varies with the personality of the spectator? As he put it, “If you are like a villain, will you like a villain?” So via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk the team ran questionnaires testing how personality types matched tastes in villains. Not to spoil their public announcement, I’ll just say that the results seem to confirm the belief that the most dangerous creatures on earth are young human males.

There was a lot more here than I can report, including provocative keynote addresses from Professors Anne Bartsch and Cornelia Müller (presenting work done with Hermann Kappelhoff). There was also a moving tribute to Torben Grodal, a central force in SCSMI and a leading-edge theorist applying evolutionary psychology and embodiment theory to traditional genre studies.

And, since SCSMI wants to understand how creators create, there was a film and its maker.

Without bullshit

In the past, our conferences have featured Lars von Trier and Béla Tarr, talking with us about their work. This time the guest was Thomas Arslan, a prominent “Berlin-school” director, who brought his 2010 film In the Shadows (Im Schatten) to the lovely Cinema Metropolis.

The film is a dry, hard-edged crime exercise. Trojan, fresh out of prison, comes to his boss to claim his share of the loot. In a tense confrontation he manages to get some of what he’s owed, but he’s now a target for elimination. He searches for a new robbery scheme and settles on the heist of an armored car. As usual, things don’t go as planned, particularly due to the intervention of a crooked cop.

Shot in a laconic style, In the Shadows took advantage of the Red One camera to produce remarkable depth in dark surroundings. (We saw it as a print because in 2010 theatres weren’t quite ready to show digital files. The print looked fine.) The drab locations complemented the anti-psychological impact of the story. Characters barely speak, the music is spare and almost subliminal, and the framing doesn’t accentuate the action expressively. In his post-film discussion, Arslan explained that the style grew out of the small budget and the rapid schedule. The result was a sort of modern B-film, avoiding the excess of CinemaScope and explosive chase sequences.

Arslan refuses to glamorize his gangsters, but he summons up sympathy for Trojan by minimal means. The protagonist is a solid, efficient professional, and he’s loyal to his boss until he realizes he’ll be betrayed. And as Hollywood screenwriters would remind us, you can sympathize with someone who’s been treated unfairly. I liked the unfussy handling of the story; it was a bit reminiscent of Rudolf Thome’s bare-bones Detective (1968). Arslan would be a good director to shoot a Richard Stark noir. “He does it without bullshit,” Arslan said of his thieving protagonist. It’s a good description of Arslan’s own technique.

SCSMI continues its tradition of merging humanistic inquiry with findings from empirical science. We can fruitfully ask questions that cut across traditional boundaries if we ground those questions in clear concepts and solid evidence. Our gathering next year moves back to the States–Grand Rapids, no less. More fun on the way.

Go here for earlier years’ coverage of SCSMI conferences.

On Richard Stark noir novels, see here and here. In the Shadows would fit nicely into my discussion of conventions of the heist film.

My own SCSMI contributions were two: a tribute to Torben Grodal and a little talk on contemporary women’s domestic thrillers (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, etc.). I may post the latter as a video lecture later this summer.

James Cutting lecturing at the SCSMI conference.

Posted in Film comments, Film genres, Film technique: Editing, Film theory: Cognitivism, Narrative strategies, National cinemas: Germany, Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Cognitive film studies: The Hamburg Variations open printable version

| Comments Off on Cognitive film studies: The Hamburg Variations

|