Saturday | April 13, 2019

Making Montgomery Clift (2018).

DB here:

Our days and nights at our annual film festival would have been hopelessly frustrating if we hadn’t already seen several of the fine items on offer. At other festivals we caught Asako I and II, Ash Is Purest White, Dogman, The Eyes of Orson Welles, The Girl in the Window, Girls Always Happy, The Image Book, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Lucky to Be a Woman, The Other Side of the Wind, Peterloo, Rosita, Shadow, Styx, Transit, and Woman at War. As you can see, our programmers assembled a spectacular array of movies. Most of these we’d happily watch again, but there were so many new offerings we had to resist.

With this elbow room I could pay attention to three documentaries I’d been looking forward to. They had all the appeal of a fictional film, with keen plots and tricky narration and fascinating characters. It didn’t hurt that two were about world-class celebrities and the third appealed to my deepest conspiracy-theory instincts.

Heart of Glasnost

Werner Herzog’s Meeting Gorbachev was a surprisingly conventional effort for this legendarily odd filmmaker. As my colleague Vance Kepley remarked, Herzog typically makes documentaries of two types. He probes eccentric personalities (the “ski-flyer” Steiner, or a man trying to hang out with grizzly bears) or he treks into remote, dangerous landscapes (Antarctica, a swift-moving volcano, the fires of Kuwait).

But this portrait of Mikhail Gorbachev is neither. Herzog’s interview with the elderly but still vigorous Soviet leader is interrupted by biographical inserts tracing his career, his struggles, and his policies. Newsreel footage and other talking heads provide context in a mostly straightforward account of the man’s life and work. Only a story about tree slugs briefly diverts Herzog’s attention.

The film revives our appreciation of a politician many people have tried to bury. Gorbachev emerges as a thoughtful, upbeat man who tried to make the Soviet Union more democratic and open to the popular will, to create Communism with a human face. But he triggered events that cascaded too quickly. He broke up the USSR but also cleared a path for economic collapse and a corrupt kleptocracy. His suggestion for his tombstone inscription: We tried.

Herzog’s montages dramatize the breakdown of national borders, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the coup that destabilized reforms while Gorbachev was away from Moscow. The main principle of swimming with sharks in a bureaucracy is: Don’t tell anybody what you’re going to do until you do it. The 1991 unseating of Gorbachev by Yeltsin reminds me of a second: Don’t take vacations.

Meeting Gorbachev is actually a double portrait, because Herzog puts a good many personal feelings into it. He remembers the emotion he felt as Germany reunited. Gorbachev’s call for “a common European home” rouses him to recall his youthful Wanderjahr when he walked across the continent.

Although I don’t think the name Trump is mentioned, his shadow falls over the whole film. Portraying a sane, reasonable leader today seems virtually a bid for controversy. Gorbachev reminds us of the reductions in nuclear weaponry that he negotiated with Reagan and Thatcher. “People say that Reagan won the Cold War. Actually, it was a joint victory. We all won.” The idea of pursuing policies that benefit the whole world seems oddly old-fashioned right now.

When Herzog gives us a glimpse of a robotic Putin peering down into the casket of Gorbachev’s beloved wife, we’re forced to register what Russia has become, and how the US is now complicit with it. Maybe this film has more of the director in it than I initially thought. As Herzog dared to declare in an earlier film, Nosferatu lives.

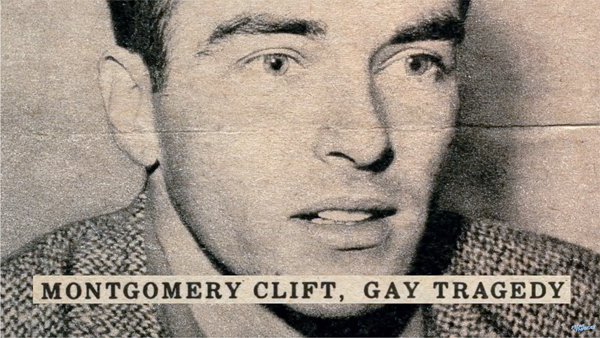

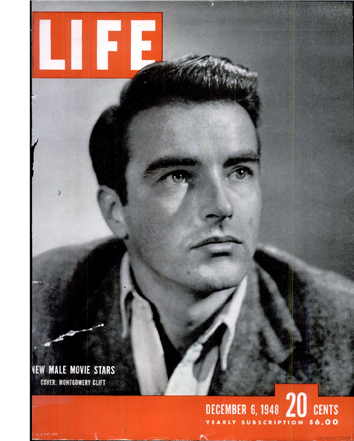

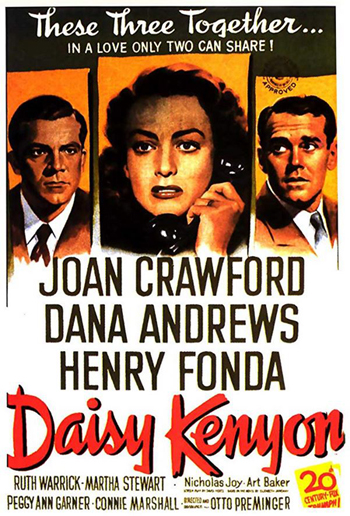

Unmaking an icon

Whenever I see Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift kiss in A Place in the Sun, I think: Here are the two most beautiful people in the Western world. I’m not alone. Clift was one of Hollywood’s most celebrated stars after the war, partly because he didn’t easily fit the molds of either the old guard or the new.

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan). The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

In this context, Clift looks like cannon fodder. Put him alongside Lancaster in From Here to Eternity, and you’ll find it hard to believe he’s the prizefighter; in that movie, only Sinatra looks skinnier. Delicate, with an innocent stare and an angular body, a wide-eyed Clift takes over his debut film, Red River (1948), from the lumbering John Wayne. Hawks claimed he told Clift that if he quietly watched the action from behind his tin coffee cup, he could steal every scene.

Clift carved out a space all his own. Late in his career, the tremor in his voice and a wary tilt of the head gave him antiheroic quality, as in Wild River (1960). Not for him the over-underplaying of Brando or the unpredictable gestures and dialogue cadences of James Dean. He has his own method, not The Method.

One of the many merits of Making Montgomery Clift, a fascinating documentary by Robert Clift and Hillary Demmon, is that it triggers such thinking about the actor’s craft. Emerging from a hillock of papers, home movies, video tapes, and audio tapes, the film documents two dramas–that of Clift’s life, and that of the process through which complex human beings get flattened into media clichés. As a bonus, we reap many insights into how actors shape their performances, sometimes against the grain of the script they’re handed.

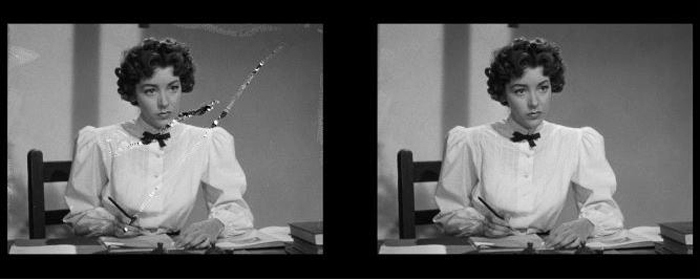

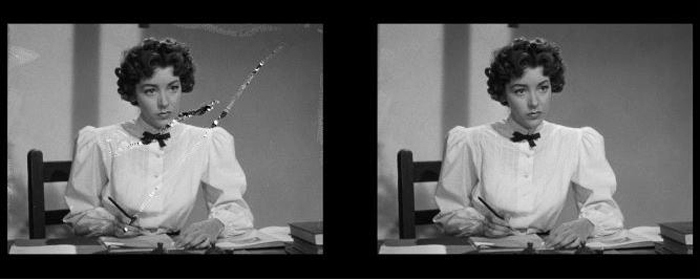

On the life, we learn that Clift was often a buoyant, bisexual fellow, not the brooding and moody figure of legend. He was also a demanding artist who turned down juicy parts. When he signed up for a role, he insisted on vetting the script and sometimes rewriting it. In split-screen Clift and Demmon present the page on the left, scribbled up with Monty’s notes and excisions, and then run the scene alongside. The excerpts they give us from The Search and Judgment at Nuremberg show how a committed actor can strip an overwritten scene down to an emotional core.

If nothing else, Making Montgomery Clift shows us how performances shape movies: the actor as auteur. But it’s exactly this analysis of craft that’s missing from most film biographies. Those doorstop volumes revel in scandal and exposés because publishers think that a straightforward account of hard-won artistry–the sort of thing we routinely get in biographies of composers or painters–doesn’t suit movies. The result is glamor, excitement, sad stories, and banal interpretations rolled into one fat book.

This is the other drama so patiently traced by Clift and Demmon. They show how two 1970s biographies set a mold for the Tragic Homosexual story that has dogged the Clift legend ever since. Just as the filmmakers pay attention to the movies, they provide close readings of passages in the books, and the evidence of sensationalism, inaccuracy, and offhand speculation is pretty damning. One description of Clift’s injured face after his 1957 car crash savors brutal detail. And it’s not just the ambulance-chasers; passages from John Huston’s autobiography also radiate bad faith.

Clift understood that cookie-cutter journalism would oversimplify him. Thanks to the endless tapes he and his brother Brooks made of their phone conversations, we hear his quick condemnation of “pocket-edition psychology.” There’s a continuum between the tabloid headline, the talk-show time-filler, the celebrity memoir, and the bulging star bio. All try to iron out the wrinkles. During the Q & A, Robert Clift talked about traditional biographies as exercises in taxidermy: “It feels so real because it’s dead.” Hillary Demmon remarked that they wanted to “open up Monty to more readings.”

Making Montgomery Clift proves that academic talk about the “social construction” of this or that isn’t hot air. The film ranks with Errol Morris’s Tabloid as combining a fascinating life story (full of, yes, drama) with a serious argument about how celebrity culture reduces that story to captions and soundbites. Let’s hope the film makes its way to wider audiences, in theatres and on disc and streaming services. It belongs in the library of every college and university, so that students can get acquainted with an extraordinary performer, appreciate the art of star acting, and witness how the media shrink people to less than life size.

In the crosshairs of history

Like other baby boomers, I’m a connoisseur of conspiracy theories. But we have an excuse. Today’s kids grow up with school lockdowns and street shootings; we had assassinations. Patrice Lumumba (1961), Medgar Evers (1963), John Kennedy (1963), Lee Harvey Oswald (1963), the Freedom Summer murder victims (1964), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King (1968), and Robert Kennedy (1968): this cavalcade of killings made political life seem a theatre of Jacobean intrigue.

Not the least of these was the 1961 death of the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammerskjöld. Hammerskjöld had pressed for peace in the Middle East and was a patient advocate for decolonization in Africa. En route to the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga, his plane crashed. For years many people, including former President Harry Truman, believed that the plane was shot down in order to murder Hammerskjöld.

So of course I had to see Mads Brügger’s Cold Case Hammerskjöld. It did not disappoint.

At first it seems cutesy, with the filmmaker dictating his findings to two African women typists, who occasionally turn to question him. He’s both pedantic and flamboyant (wearing white clothes to match the habitual outfit of a villain he will expose). In contrast there’s the veteran Hammerskjöld researcher Göran Björkdahl (on the right above beside Brugger). Björkdahl is a steady presence as the men question witnesses to the crash and then, crazily, set out to dig up the site. When they’re forbidden to do so, you might think that we’ve got another film about not making a film.

Instead, in the spirit of Morris’s Thin Blue Line, the story we’re investigating drifts into another story, and then another, as documents and witnesses and people who refuse to talk to the filmmakers lead to some appalling charges. Let’s simply say, to preserve the film’s shock value, that the Hammerskjöld case reveals SAIMR, a white supremacist militia for hire. The most horrifying claim about SAIMR and its leader is broached by a well-spoken mercenary purportedly haunted by guilt. His claim has been contested by researchers (as reported in the New York Times). Even if his charge doesn’t hold water, though, the existence of SAIMR seems well-documented.

We conspiracy theorists are often told that history proceeds by accident, not by intention. Yet some intentions succeed splendidly (viz. the killings itemized above), and some succeed by luck. Perhaps the darkest intentions chronicled in Cold Case Hammerskjöld were too crazy to be implemented. But that doesn’t lift responsibility from the feverish minds who dreamed them up, or from the institutions–perhaps mining companies, perhaps MI6 and the CIA–that gave them a hand. In an era when white supremacy has come on strong, Brügger’s film will remain the provocation it was intended to be.

One more entry will talk about still more films at this festival which so generously spoils us.

Thanks to film festival coordinators Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, Zach Zahos, and their dedicated staff for this year’s wonderful event.

Cold Case Hammerskjöld.

Posted in Actors, Directors: Herzog, Documentary film, Film comments, Hollywood: Artistic traditions |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas, but docus as dramas open printable version

| Comments Off on Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas, but docus as dramas

Wednesday | April 10, 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).

Posted in 3D, Animation, Directors: Hong Sangsoo, Directors: Lubitsch, Festivals: Wisconsin, Film comments, National cinemas: Middle East, People we like |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019 open printable version

| Comments Off on Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Monday | April 8, 2019

DB here:

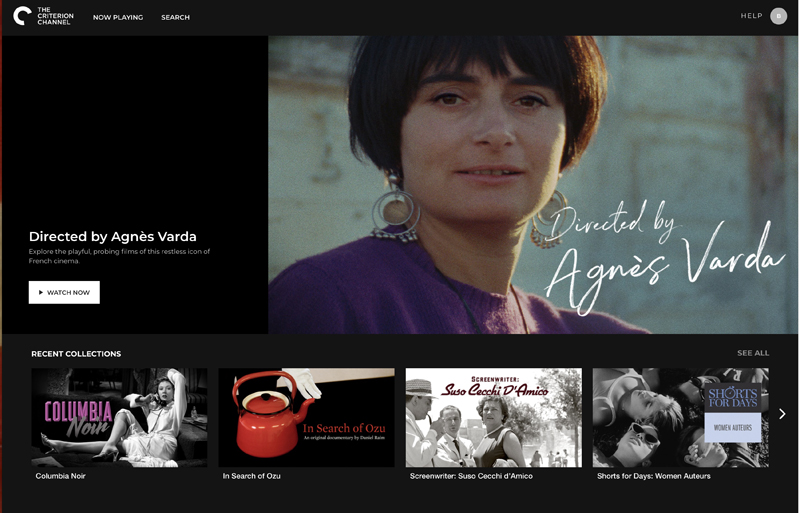

The Criterion Channel is up and streaming in the US and Canada as of today. You can browse the offerings here. Some basic questions are answered here. For help activating your account, try here.

Using Apple TV, I found it very easy to get access. I was immediately and flawlessly playing The Big Heat, Taipei Story, La Pointe Courte, and Le Amiche, that unjustly ignored Antonioni masterpiece.

For background and news on forthcoming options, check out this interview with Peter Becker. For those who miss the Hollywood side of FilmStruck, the Channel will be streaming studio-era classics as well as silent, foreign-language, and independent titles.

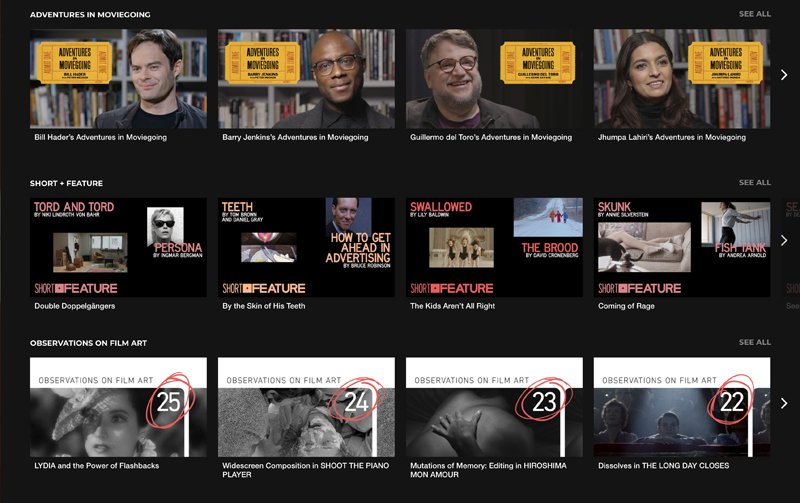

And all the extra features from FilmStruck–Adventures in Moviegoing, Ten Minutes or Less, Split Screen, Short + Feature, plus the supplements and interviews and bonus felicities you’ve come to expect from Criterion–will continue and accumulate in an archive. The menu includes our Observations on Film Art series, re-launching this month with me talking about flashbacks in Lydia. (It was up briefly in the waning days of FilmStruck. There’s a blog entry about it too.)

At some point, a vast array items from the Criterion/Janus library will be accessible as well. That’s the iceberg underneath the surface. How many films? Wait and see, and be astonished.

This is truly a momentous event in our film culture. We want to thank the Criterion team, all of them devoted film lovers, for working so hard to make this ever-expanding treasure-house available.

Under our Criterion Channel category, you can find all the blog entries devoted to our installments there, including those from the FilmStruck days.

Posted in Criterion Channel, FILM ART (the book), Film comments, Readers' Favorite Entries |  open printable version

| Comments Off on The Criterion Channel: The best news for film culture you will hear today (and probably all year) open printable version

| Comments Off on The Criterion Channel: The best news for film culture you will hear today (and probably all year)

Sunday | March 31, 2019

Kristin here:

Given the current year-round feverish speculation about the Oscars, it was perhaps inevitable that the campaign for performer-awards nominees for the three leading ladies of The Favourite was what drew attention to their relative prominence in the film. As Gold Derby (the website subtitled “Predict Hollywood Races”) said during the lead-up to the announcement of the nominees, “The film inspired a lot of debate in the early days of the Oscar derby as to what categories the film would campaign its three actresses [for].” Ultimately it was decided to place Olivia Colman in Best Actress and Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz in Best Supporting Actress. (For those who are interested, this story gives a detailed run-down of those occasions on which two or even three performers from the same film were nominated opposite each other in the same category.)

Esquire was one among many media outlets stating the same opinion: “Yes, Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz are both leading players in The Favourite, and yes, it’s probably category fraud that they were submitted in the supporting category to bolster Olivia Colman’s chances to win Best Actress. It is what is, and we must live with the fact that these two will get the nomination.” Indeed, that was what happened.

Stone and Weisz showed good grace in reacting to the studio’s decision–wise even without the benefit of hindsight–to campaign for Colman as the sole best-actress nominee. They did not, however, suggest that she was the sole protagonist of the film. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Weisz remarked, “I think Fox Searchlight was quite brave to make a film with three really complicated female protagonists. It’s doesn’t happen every day, sadly.” Every year The Hollywood Reporter interviews prominent but anonymous Academy members about their opinions and preferences in the main categories. This year an unknown director complained of the best-actress race, “I don’t understand what [Olivia Colman’s] doing in this category, or what the other two [Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz] are doing in supporting–all three should be the same.” The notion that the three roles were roughly equal in importance was expressed widely during awards season. Google “The Favourite” and “three protagonists,” and many hits will show up in the trade and popular-press coverage.

This notion of three protagonists intrigued me. I believe that the structures of many classical narrative films depend to a considerable extent on how many protagonists they have, what those protagonists’ goals are, and what sorts of obstacles they encounter along the way–often obstacles that lead or force them to change their goals. I based my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), partly on that idea. For close analysis I chose four exemplary films with single protagonists (Tootsie, Back to the Future,, The Silence of the Lambs, and Groundhog Day), three with parallel protagonists (Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, and The Hunt for Red October), and three with multiple protagonists (Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters).

Single protagonists are the commonest, and their obstacles are typically generated by single antagonists. Multiple protagonists are somewhat less so. They tend to break into at least two types. There are shooting-gallery plots like Alien, in which the protagonist is the one who, predictably or not, survives the gradual killing-off of the other main characters. Then there’s the network-of-relations plot, like Parenthood and Hannah, in which separate plotlines are acted out, with the protagonist of each related by blood or friendship to the protagonists of the others. More difficult to pull off is the multiple-protagonist plot where the characters are linked by an abstract idea and have minimal or tenuous relationships to each other–Love Actually being a masterfully woven example. (Would that it had existed when I wrote my book!)

The parallel-protagonist plot is relatively rare. I’m not talking about a film with two main characters who are closely linked and sharing the same goal. The buddy-film, most obviously two partner cops as in the Lethal Weapon films, is a common embodiment of this goal, as is the romance where the couple are in love from early on but face obstacles posed by others, as in You Only Live Once.

Parallel protagonists are not initially linked but pursue separate goals that usually bring them together. This might involve a romance conducted from afar, as in Sleepless in Seattle. One character may know the other and seek to be more like him or her, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. In those two cases, the main characters end by succeeding as they come together and become friends. (Hair would be another example I could have used.) In Amadeus, on the other hand, Salieri fails in his desperate attempt to replace Mozart in public favor and to essentially become him by stealing his Requiem and passing it off as his own.

The triple-protagonist plot

I never considered the category of triple protagonists, simply assuming they would belong within the multiple-protagonist films. Perhaps they do, but The Favourite raises the possibility that such films have a distinctive dynamic, somewhat akin to the parallel-protagonist plot but more complex, or at least more complicated.

Balancing two protagonists who have more-or-less equal stature in the plot is probably not much more difficult than the other types of classical plots. I think that’s largely because these two main characters can come together by the end and become the romantic couple or the buddies who could easily have been the main figures in a dual-protagonist film. Three protagonists, however, are very difficult to balance without one or two of them becoming mere supporting players by the end.

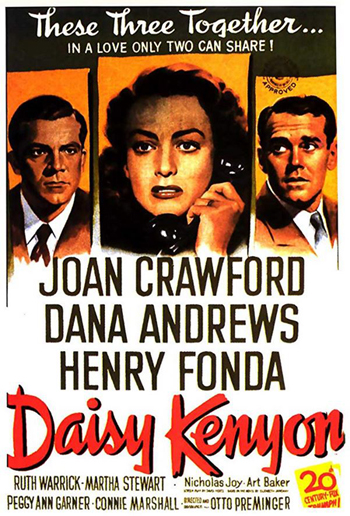

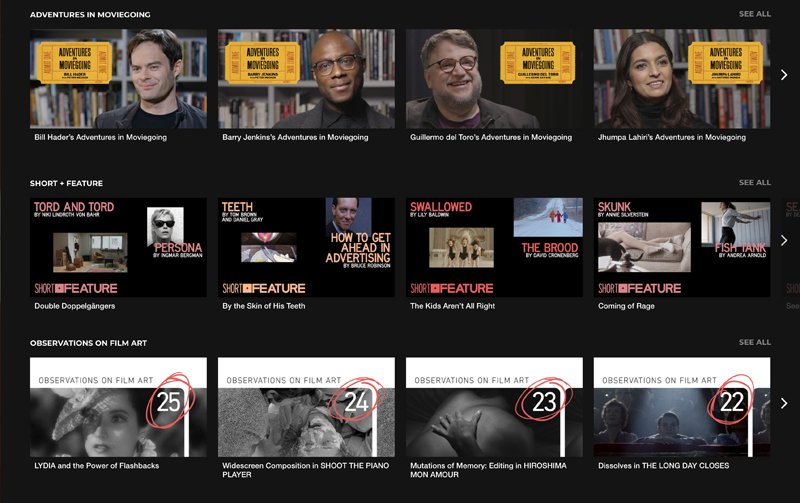

Across the history of classical filmmaking, there are probably a fair number of examples of such a balance being achieved. It’s not easy to think of more than a few, though. The first one that came to my mind is Otto Preminger’s underappreciated Daisy Kenyon (1947). In it Daisy is the mistress of a prosperous married lawyer, Dan, who refuses to divorce his wife and marry her. She meets a genial but traumatized war veteran, Peter, and marries him, but when her initial lover finally files for divorce, she is torn between the two. More about Daisy Kenyon later, the point here being that a triple-protagonist plot is not out-of-bounds for Hollywood and that two people struggling to win a third’s favors is an obvious situation to use in such a film.

The first half of The Favourite displays the long-established relationships between Queen Anne and Sarah. Sarah is stern and commanding with Anne, even cruel at times, and she runs political affairs in the Queen’s place. It is also clear, however, that the two love each other and that Anne, with her various physical and mental frailties, heavily depends on her friend. This half also traces the rise of unfairly impoverished Abigail, Sarah’s cousin. She ingratiates herself with Anne by helping nurse her gout and providing sympathy and deference; she even induces the semi-invalid Anne to dance.

Up to this point we are cued to sympathize with Abigail. She has been the innocent victim of misfortune and is treated cruelly once she arrives at court and Sarah hires her as a scullery maid. The midway turning point, as I take it, happens in the scene where Abigail shoots a pigeon and the blood spurts onto Sarah’s face. Immediately after this a servant arrives to say that the Queen is calling for Abigail rather than Sarah. Abigail is implied to have tipped the balance toward her being accepted as Anne’s favorite.

After this point, we suddenly start to see Abigail’s conniving side, and the pendulum swings as we grasp that Sarah has been displaced in the Queen’s affections through Abigail’s lies about her. In this second half, we are led to recall that Sarah, dominating though she is with Anne, truly loves her and is far more qualified to help run the state than frivolous Abigail is. By the end, all three have managed to make each other and themselves miserable, though Sarah still has her husband and manages to take exile abroad in her stride. None of them emerges as the most important character.

One might argue that Abigail functions as a conventional antagonist. After all, she drugs Sarah’s tea, nearly causing her death–and showing no compunction about it. Yet she, too, is pitiable. Her father gambled her away into marriage with a stranger, and early in the film she is bullied by the other servants. Sarah has her unlikable side and at one point attempts to blackmail Anne by threatening to make public the Queen’s love letters to her–an act that finally drives Anne to reject her. Before that rejection, however, Sarah burn the letters instead, confirming her inability to betray queen and country.

In a review on tello Films Karen Frost writes,“While Stone may receive a modicum more screen time than the other two, this movie really has three protagonists, all of whom are compelling in their own way.” I suspect a lot of spectators, including me, share this impression that Abigail is onscreen or heard from offscreen marginally more than Anne or Sarah. That said, it’s very difficult to measure the presence of each character, given how short the scenes are and how often the women come and go from the rooms where the main action is occurring. And does a scene like the one at the top of this section, where Anne and Sarah converse while Abigail stands mutely in the distance, give equal weight to all three? Perhaps, in that we are here conscious of the latter’s simmering resentment.

In a comparable scene, Abigail is pushing the Queen in a wheelchair. Anne becomes upset and tries to stagger back to her room. We follow her and concentrate on her struggle and emotions for some time before Abigail appears again with the chair. Should we consider this one scene between the two, or actually three scenes, with the two together, then Anne alone, and then the two together again? Even within scenes where two or three of the women are present, weighing their relative prominence in the scene presents difficulties.

The casting is crucial in such a film, since the relative prominence of the actors tends to affect our judgment of their characters’ importance. Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone were both Oscar-winning stars before The Favourite‘s release. Olivia Colman was not well-known in the US, but she had had a long and prominent career on television and occasional films in the UK, The Favourite‘s country of origin. Certainly as Anne she gains the audience’s sympathy early on and becomes plausible as a protagonist alongside the other two.

Scenes and twists

I decided that rather than attempt to clock screen time, I would count how many scenes each character had alone, how many involved two of them, and how many showed all three together. When I say “alone,” I mean only one of the three women is present, though often she is interacting with the main male characters, Lord Treasurer James Godolphin, Leader of the Opposition Robert Harley, and Baron Masham. Given the many very short scenes, the intercutting, the presence of the characters in the backgrounds when the others are emphasized, and the brief intrusion of a character into a scene that overall emphasizes one or two of the other women, my breakdown into segments can’t be precise.

I’ve compared the numbers of scenes devoted to the various combinations of characters in the first and second halves of the film, given the reversed situations of Sarah and Abigail in those large-scale sections.

First, the characters alone:

Anne has only 1 solo scene in the first half/3 in the second. (Total 4)

Sarah is alone 2 times in the first half/8 in the second. (Total 10)

Abigail is alone 7 times in the first half/9 in the second (Total 16)

Abigail’s larger number of scenes apart from the other two women occur largely because she is duplicitous and her situation changes drastically. Anne and Sarah behave straightforwardly, the former because she is too addled to be capable of deception and the latter because she is fundamentally honest, if sometimes brutally so.

Abigail’s duplicity must be revealed gradually. This is done to a considerable extent through two important relationships that help reveal that she is not the sweet young thing that we may have initially taken her to be. In the first half, Harley tries to bully her into acting as a spy in Anne’s bedchamber, passing on to him the political tactics and decisions of the Queen and Sarah. At first it is not clear that Abigail will comply. She also has aggressively flirtatious scenes with Masham. Initially she seems to be Harley’s victim and genuinely attracted to Masham, if in a rather eccentric fashion. Almost immediately after the midway turning point, however, Abigail passes secret information to Harley for the first time. Later, after Anne permits her to marry Masham, it is revealed that Abigail’s primary motive was to restore her lost social standing.

Scenes with Queen Anne with one or the other or both other women:

Anne with Sarah: 6 times in the first half/7 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with Abigail: 3 times in the first half/10 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with both: 6 times in the first half/5 in the second (Total 11)

Here the balance among the three protagonists becomes apparent. Whether intentionally or not, the scriptwriters gave Sarah and Abigail the same number of scenes alone with the queen. Abigail’s access to the Queen is naturally considerably greater in the second half of the film, as she gains her status as the favorite. Surprisingly, though, Sarah’s scenes with Anne are balanced between the two halves. I take this to reflect the Sarah’s determination not to be defeated and also the lingering friendship and genuine love that the two have shared since childhood. If we are to realize by the end that Anne has made a dreadful mistake by rejecting Sarah and sending her into exile, we must be reminded at intervals of how vital Sarah had been in helping Anne run the affairs of state.

The fact that Anne’s scenes with both other women are balanced between the two halves functions to allow us to continue comparing the behavior of both women toward the Queen. We slowly grasp Abigail’s perfidy and Sarah’s prickly steadfastness. The latter is made particularly poignant in Anne’s and Sarah’s final conversation, which takes place through the closed doorway of Anne’s room and ends with Anne rejecting her old friend, despite apologies and pleading.

Queen Anne is in a total of 41 scenes, Sarah in 44, and Abigail in 50, which does suggest that the latter has more screen time overall. The reason for this is probably not that she is more important, but that Sarah and Anne have an established, loving relationship at the beginning, which is easy to set up. Abigail must claw her way up from the scullery to the Queen’s bedroom, which takes more time to accomplish.

The screen time, however, is not the key factor. The film’s impact on the spectator depends to a considerable degree on our struggle to figure out which, if any, if these characters we might identify or sympathize with. There are such frequent shifts of tone and of what we know about each of them that our expectations are systematically undermined in the course of the plot.

In an interview on Deadline Hollywood, Tony McNamara, one of the scriptwriters, describes the effects of having three protagonists:

I thought it would be hard, but it was actually kind of liberating to have three, because it just gave you more options and places to go. Often, an action in a script has a reaction, but just one antagonist and protagonist. But because it’s three protagonists, there was always this cascading effect, and there were more twists. It was fun to have options, [though] there was work to do, making sure that the three were in balance, throughout.

Twists the film has in abundance. Our attitudes toward the characters change time and again. The scene in which Sarah starts letter after letter to Anne, trying to regain her favor, encapsulates all three women’s mercurial behavior. Her openings range from violent resentment (“I dreamt I stabbed you in the eye”) to fondness (“My dearest Mrs Morley”–her pet name for the Queen). The latter is the one she sends, but Abigail consigns it to the fire, finally making any reconciliation between her rival and the Queen impossible.

The ending, with its superimpositions of Anne’s rabbits over the faces of her and Abigail has been criticized as a failure to provide a satisfactory conclusion to the tale of the three protagonists. I’m not sure it is a failure of invention. Abigail’s insinuation of herself into the Queen’s favor began when she noticed the rabbits in the royal bedroom and elicited Anne’s tale of the loss of all seventeen babies she had had, with the rabbits acting as substitutes for them. Abigail had expressed an apparently deep sympathy, but in the final scene Anne sees Abigail capriciously and cruelly press her foot down on one of the rabbits. All illusions that her new favorite has loved her better than Sarah had vanish at this point, if they had not already. The two are portrayed as trapped in a relationship based on grief over unthinkable loss on the part of one and hypocritical manipulation by the other.

Preminger’s balancing act

Daisy Kenyon differs vastly from The Favourite, to be sure. Still, it’s a romantic triangle situation, and the woman who must decide between her two suitors is indecisive up until just before the ending. Dan and Peter are equally plausible as a final choice. Both have faults. Dan is content to carry on his adulterous affair with Daisy indefinitely, and Peter spies rather creepily on her after meeting her, secretly following her to a movie theater so that he can “accidentally” meet her when she comes out. Both clearly are in love with her.

Preminger also managed to cast three stars of more-or-less equal stature. Andrews had gone from supporting roles to the lead in Laura (1944) and was just coming off the success of The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Fonda had had both leading and supporting roles since the mid-1930s and starred in such films as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), and My Darling Clementine (1946). There is no Ralph Bellamy, the obvious Other Man, here.

There’s another resemblance to The Favourite, in that the man Daisy ultimately chooses then says something that creates a final twist–indeed, it’s the last line of the film. He reveals that not all is as we assumed, and we may be left wondering if, like Queen Anne, Daisy may regret her choice.

Another obvious triple-protagonist film is Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), which once again presents a romantic triangle centering on a heroine who is understandably indecisive in choosing between Gary Cooper (George) and Fredric March (Tom). She moves in with both with an agreement that they will avoid sex. She succumbs to George’s charms when Tom is away and to Tom’s when George is away, and when jealousy between the two men breaks out, marries her rich but boring boss (Edward Everett Horton). The pre-Code ending sees Gilda back with Tom and George in an arrangement that seems no more likely to remain sexless than the first one had.

Again the casting makes the two male protagonists seem equal. March and Cooper were both rising stars at the time, with March fresh off an Oscar win for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). Cooper had achieved prominence with The Virginian (1929) and followed up with Morocco (1930) and A Farewell to Arms (1932).

This is not to say that all three-protagonist films have this triangle plot with an indecisive woman as the pivot. No doubt there are all sorts of other ways to balance three lead roles. Nor is it to say that three-protagonist films are so common and distinctive as to make me go back and revise Storytelling in the New Hollywood. Still, it’s interesting to see this kind of variant played on more familiar plot structures and to study how filmmakers can go about maintaining the necessary delicate balance.

David has an analysis of Daisy Kenyon‘s narrative maneuvers in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

Posted in Film comments, Film technique: Screenwriting, Narrative strategies, National cinemas: UK |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE open printable version

| Comments Off on Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE

|

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).