Sunday | March 24, 2019

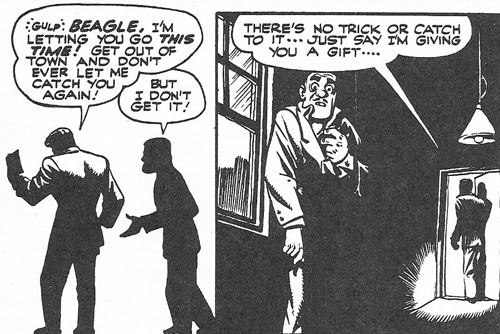

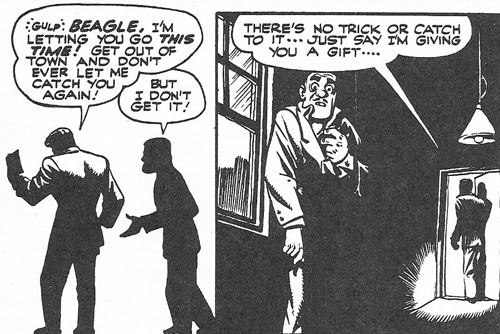

From “The Killer,” Spirit Comics (8 December 1946), by Will Eisner and studio.

DB here:

This is my final effort to cram my latest book down the resisting gullet of the reading public. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling has just come out in paperback and I’ve been using our blog to trace out some relevant ideas that surfaced in recent books and DVD releases. The first entry dealt with some general issues, the second with popular culture’s drive toward variation, the third with craft and auteurism. This one has murder on its mind.

Noir as mystery and mystique

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

Crime looms large in Reinventing Hollywood. But I forsake the usual category of film noir. It didn’t exist as a concept for the filmmakers or audiences of the day. It’s the creation of critics, first overseas and then, much later, here at home. That doesn’t make the category invalid, though. Many art-historical categories (Baroque, Gothic) are later inventions, and those can be illuminating. Still, I think we gain some understanding if we situate our inquiry, for a time at least, at the level of what people seemed to be trying to do at the time.

Put it another way. By focusing on noir as the model of Forties narrative, we miss the ways in which the films we pick out under that rubric participate in wider trends. We miss, for instance, the new importance of mystery in all plotting of the period.

In the 1930s, mystery was mostly confined to detective stories. Think of your prototypical 1930s movie; it’s unlikely to have a mystery at its center. (Okay, maybe we’re curious about the identity of Oz the Great and Powerful.) In the 1940s, though, filmmakers began to scatter mystery devices into other genres. Mystery became a central storytelling strategy for personal dramas (Citizen Kane, 1941; Keeper of the Flame, 1943), romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan, 1945), war films (Five Graves to Cairo, 1943), social comment films (Intruder in the Dust, 1949), and domestic melodrama (Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Locket, 1946; A Letter to Three Wives, 1948). Some of what we call noir is part of this trend.

Over the same period, a fairly minor genre got promoted. Psychological thrillers can be traced back to Gothic novels and sensation fiction, but they became a distinct part of crime literature in the 1930s. They became an important genre for cinema in the 1940s, and so Reinventing Hollywood devoted a chapter to films like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

These aren’t canonical “noir” films, at least if your notion of noir stems from hard-boiled fiction. Some rely on the guilty-party plot exemplified in C. S. Forester’s novel Payment Deferred (1926), Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope (1929), and Anthony Berkeley Cox’s novel Malice Aforethought (1931). Less famous but just as interesting is the “woman-in-peril” thriller.

This was an upmarket version of romantic suspense novels associated in earlier decades with Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), one of the top-selling books of the 1940s, lifted the genre to respectability. Revisiting traces the wide-ranging variations that followed in film, fiction, and theatre. (An early draft of that chapter is elsewhere on this site.) Mystery is central to this subgenre. Who is endangering the protagonist? What are the real motives of the people around her, especially her lover or husband? Are her friends complicit? How will she escape?

The gynocentric thriller remains powerful in popular literature today. We’re currently in a rapid-fire cycle of it, typified by the work of Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn. Some of the books have come to the screen: Gone Girl (2014), The Girl on the Train (2016), and A Simple Favor (2018). The HBO series Big Little Lies (2017-on), turns a fairly satiric domestic-suspense novel into a heavier exploration of spousal abuse. I’ll be writing more about this cycle later (and giving a paper on it this summer), but let me note two recent examples. One takes its Forties sources for granted, the other flaunts them. Both are coming to a screen near you.

In Alex Michaelides’ new novel The Silent Patient Alicia Berenson, an emerging painter, is found guilty of shooting her husband. Because she seems in permanent shock and refuses to speak a word, she’s confined to a mental institution. There the ambitious young psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to ferret out why she remains silent. The narration alternates, Gone Girl fashion, between Theo’s first-person investigation and Alicia’s diary of events leading up to the killing.

It’s a spare tale narrated in a clumsy style that doesn’t distinguish the two voices. And it reminds us that if you become a character in a novel or movie, don’t get into a car. But it does show the persistence of Forties strategies.

There’s the Crazy Lady (recalling Shock of 1946, above, and Possessed of 1947, as well as John Franklin Bardin’s 1948 novel Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There’s the sinister side of the artworld, with a predatory dealers, a demented painter, and portraits that suggest sinister psychic forces. There’s the apparently rational man who becomes obsessed with a woman in a picture (as in Laura, 1944). There’s a mythological parallel to the heroine (here, Alcestis; in The Locket of 1946, Cassandra). There’s the therapeutic motif of a doctor falling in love with a mentally disturbed patient (Spellbound, 1945). And there is, of course, a twist depending on suppressive narration.

The Silent Patient quietly absorbs these Forties conventions, with virtually no mention of the tradition. At the other extreme sits the self-conscious geekery of A. J. Finn’s The Woman in the Window. In an earlier entry on the eyewitness plot I swore I wouldn’t give space to this novel, largely because I resist people swiping titles of movies I admire. But after alert colleague Jeff Smith told me, “It’s as if he read your Forties book,” I figured I could break my rule.

Indeed this eyewitness thriller relies on a great many narrative tricks from the period. We get a Crazy Lady, dreams, hallucinations, an unreliable narrator, the drama of doubt, flashbacks within flashbacks (with the revelatory one coming at the end), and a Gothic climax punctuated by lightning bursts. Also, inevitably, a car crash.

The book’s epigraph comes from Shadow of a Doubt, and the pages that follow are littered with references to 1940s movies. Our homebound heroine lives in thrall to DVDs and TCM, though her impending fate gives a new meaning to “Netflix and chill.”

The Woman in the Window is soaked in contemporary movie-nerd culture. The heroine updates Jeffries’ tech gear in Rear Window by shooting video footage of the suspects across the way. She mentions Kino and Criterion discs, and even refers to “diegetic sound.” (Has she read Film Art: An Introduction?}

Like The Silent Patient, Finn’s book illustrates how much modern thrillers owe to Forties movies. But it also exemplifies how noir has become a kind of brand and a signal of hip tastes. Maybe that’s a reason to back off the label for a while.

Noir in brief

But let’s not back off too far. Any student of 1940s Hollywood can learn a lot from the vast literature on noir. The most recent item to cross my desk is James Naremore’s Film Noir: A Very Short Introduction. (It’s due to be published in April.) As you’d expect, the author of More Than Night will bring a wide-ranging expertise to a compact survey of books, films, and ideas.

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations: I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

In the previous two decades modernism had influenced melodramatic fiction of all kinds, and writers and artists with serious aspirations now worked at least part time for the movies.

When the trend reached a peak in the early 1940s, it made traditional formulas, especially the crime film, seem more “artful.”. . . And yet there was a tension or contradiction within the Hollywood film noirs of the 1940s. Certain attributes of modernism—its links to high culture, its formal and moral complexity, its frankness about sex, its criticism of American modernity—were a potential threat to the entertainment industry and were never fully absorbed into the mainstream.

Naremore goes on to discuss several influential writers—Hammett, Greene, Cain, Chandler, Woolrich—and key films such as The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity as examples of “tough modernism” in fiction and film. One of the virtues of the book is its sweep: it covers nearly eighty years of noir on the page and on the screen. Like everything else Jim writes, it’s essential for film fans and researchers. His recently inaugurated webpage displays his range of interests.

The Big Nutshell

Did the 1940s give us the habit of calling a movie The Big Whatever? True, we had The Big Parade in 1925 and The Big Broadcast of 1935 but it seems that the next decade was quite big on bigness. Apart from The Big Sleep (1946), we had The Big Store (1941), The Big Street (1942), The Big Shot (1942), The Big Clock (1948), The Big Steal (1949), and The Big Cat (1949). Many episodes of Dragnet, as both radio show and later TV program, had The Big . . . as their title prefix.

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink). So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

There are small-scale operations (the short con), as well as complex ensemble efforts using, naturally, the Big Store (fitted out with a fake racetrack wire). The scam shown in The Sting (1973) is a Big Store con. Maurer provides a sociological study as well: “Confidence men, like civilians, mate once or more (usually more) in their lives.” I don’t know exactly how I would have worked in a footnote to The Big Con, but I would have tried.

While Maurer was writing The Big Con, something more sinister was going on. In her four-story farmhouse, Frances Glessner Lee was laboring over the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

These were crime scenes presented on an itty-bitty scale. Little corpses—stabbed, drowned, hanging—are surrounded by the most banal furnishings. Exquisitely miniaturized chairs, rugs, lamps, beer bottles, calendars (“Corn Products Sales Company”) surround the pathetic figures. A woman stares up from a bathtub alongside tiny towels, hanging socks, and even a simulacrum of tap water endlessly gushing. Frank Harris is found drunk and crumpled in front of a saloon; the next scene shows him dead in his cell. What happened?

Ms Lee, a wealthy devotee of criminal investigation, recreated these grim tableaus as audio-visual aids for police training. Exactly how useful they were as pedagogy isn’t clear. The imagery recalls classic mysteries, and it’s not surprising that Lee was a friend of Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason. Yet her scenes have a creepy melancholy quite alien to Golden Age puzzle plots. As a testimony to the 1940s fascination with aestheticized homicide, they’re close to Weegee or Chester Gould. But they’re rendered as fastidiously as a Joseph Cornell box. I see in the Nutshells the populist Surrealism that led, at the other end of the scale, to Wisconsin’s House on the Rock (which began construction in the 1940s).

Corinne May Botz is the David Fincher of the Lee oeuvre. Her camera in The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death gets deep into the scene and renders the most upsetting images with a cold precision that matches the staging. These bits of cloth and plastic, sculpted and arranged with maniacal precision, make death at once childish and bleak. Blown up in Botz’s photos, the scenes radiate anxiety and menace. Dollhouse noir?

Frozen movies

Will Eisner, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” Spirit Comics (3 November 1946).

In Reinventing Hollywood I suggest that techniques we find in the films have their counterparts in popular novels, short stories, plays, and radio shows. Artists in these media were also exploring shifting time frames and viewpoints, voice-over narration, and other devices. I called it the multimedia swap meet, where mass-culture wares were available for use and revision (thanks to the variorum).

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover. A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

One example is shown at the top of today’s entry: an effort toward optical POV in Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Eisner renders almost all the panels on that page as subjective. At the time, films were exploring the same idea for certain scenes (e.g., Hitchcock’s work), for long stretches (Dark Passage, 1947), and for nearly the whole movie (The Lady in the Lake, 1947).

Of course Eisner’s Spirit tales evoke noir visuals as well–and become more noirish as the Forties go along, at least to my eye. Other cartoonists, particularly Chester Gould and Milton Caniff, push toward the steep compositions and chiaroscuro lighting we find in the films. I’m inclined to say that the movies got there first; I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema that noirish visual designs were often recruited for scenes of crime and mystery in the 1920s and 1930s. (A blog entry found examples from the 1910s.) I suspect that artists of the comics adopted those schemas when they started to make cops-and-robbers strips. By the 1940s, though, with Eisner and others, the visual dynamism pushed beyond what we see in most films. Except, as always, for Welles: Mr. Arkadin seems an Eisner comic brought to life.

Vanilla noir

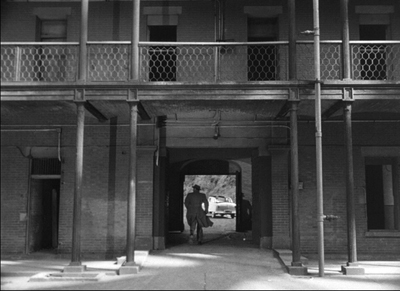

The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950).

Noir is a tricky category because it’s a cluster concept. It can refer to visual style, matters of narrative or narration (haunted protagonists, plays with viewpoint), genre (drama, not comedy), and themes (betrayed friendships, dangerous eroticism, male anxiety). Take away one dimension and you might still be inclined to call the movie a noir. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956) has a noir plotline, but its disarmingly drab images mostly lack the low-key look. And maybe someone would call Murder, He Says (1945) a noir comedy.

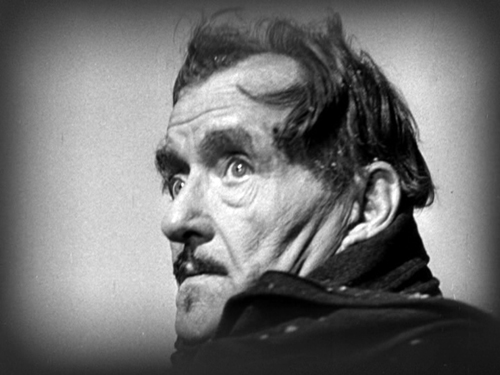

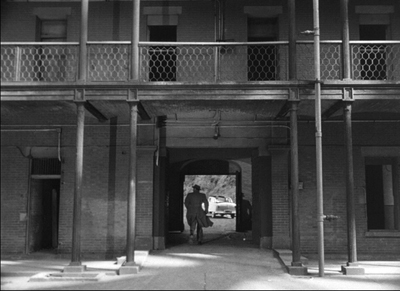

A good example of mild noirishness is The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), now made available in a handsome UCLA restoration from Flicker Alley. Ed Cullen is a tough homicide cop lured by a rich woman into a murder plot. He helps her cover it up, but his younger brother, just starting out in the police force, gets too close to solving the case.

The action climaxes in a vigorous showdown in San Francisco’s Fort Point compound. Director Felix Feist, who gave us the better-known The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947) and The Threat (1949), exploits this impressive location.

Most of the film is more soberly shot, but one long take of an interrogation uses the typical Forties image: a low-slung camera, figures deployed in depth and rearranged as the pressure intensifies.

The Blu-ray release includes a well-filled booklet and two excellent documentaries. Brian Hollis pinpoints the use of San Francisco locations and has interesting comparisons with Vertigo. A second short provides background on the participants and the film’s production, with shrewd remarks on the film’s casting by Eddie Muller. I was also pleased to see that the film, full of smokers, includes Hollywood’s favorite brand of the Forties, Chesterfields.

From Sunrise to Moonrise

Moonrise offers a different negotiation of noir conventions. The Criterion Blu-ray release, produced by Jason Altman, makes this 1948 classic available in a much better version than I’ve seen before. I discuss the opening in Reinventing, taking it as an example of a deeply subjective montage sequence, and I posted the clip online as a supplement.

After knowing the film for years, I expected that the 1946 source novel by Theodore Strauss would have some of the delirious prose we get in Steve Fisher’s I Wake Up Screaming (1941). Strauss wrote film journalism for the New York Times, so it seemed likely he would incorporate some of the pseudo-cinematic techniques of voice-over, subjectivity, and the like, as do other crime novels I mention in Reinventing. Instead, the storytelling is standard hardboiled. Here, for instance, is Strauss sketching the buildup of grudges that leads Danny to kill his long-time nemesis Jerry:

Every time his fist smacked into Jerry’s soft side or smashed Jerry’s mouth against his teeth Danny knew he was paying back. He was paying back for that first day at grade school when he was the new kid and Jerry had whipped him with the whole playground backing him. He was paying back for the night Jerry and his gang took him into the alley and tarred him because Jerry said he’d squealed to the principal. He was paying back for the scar on his shoulder left by Jerry’s cleats in scrimmage seven years ago. He was paying back for every dirty crack jerry had ever made about him or his father in public or private, to his face and behind his back. Paying back. Paying pack good.

Borzage’s movie turns this compact backstory into something much more hallucinatory.

The montage intersperses a hanged man with vignettes of his son being bullied from childhood on. First the rippling miasma seen under the credits gives way to blobs appearing as if in reflection. The camera reveals them as mysteriously projected on a wall (or is it a screen?), and then it picks up feet stalking toward the gallows.

Witnesses are revealed standing in the rain, and the camera rises to show the execution as shadows flung onto the wall/screen.

It seems more of a feverish childhood vision of the hanging rather than any veridical presentation. Cut to a view of a baby with a doll dangling over his crib. This traumatic image is followed by scenes of jeering schoolboy cruelty. (“Danny Hawkins’ dad was hanged!”)

It’s a murky, delirious passage. Its tactility, with mud smeared into Danny’s face, admirably prepares us for a film steeped in swamp water and dank foliage. Here, as elsewhere, 1940s filmmakers are rehabilitating the expressionist devices of late silent film.

The rest of the film doesn’t present such overpowering imagery, but by continuing the opening sequence in the present, following Danny as he drifts past a dance pavilion, the narration makes Danny’s fight with the bully Jerry a furious culmination of all the indignities he’s suffered.

The plot traces a familiar Forties trajectory, following a flawed but not despicable man driven to conceal a crime. In the course of his evasions, he tries to make a life with a compassionate woman. There are many wonderful scenes, including a suspenseful ride on a ferris wheel and a lyrical dance in an abandoned mansion. The lawman tracking Danny comes off as gentle and compassionate. The rippling imagery of the opening recurs in the background of shots, as if the swamp were waiting to claim Danny. As Hervé Dumont points out in a bonus conversation with Peter Cowie on the Criterion disc, all this gloom eventually clears to arrive at a sun-drenched resolution quite different from your typical noir payoff. (Though it’s faithful to the novel, as indeed most of the film’s plot is.)

This time around I was struck by the delicacy of Frank Borzage’s direction in the less flamboyant passages. This master of silent cinema knows how to let a pair of hands show distress, an effort toward tenderness, and then rejection.

Borzage was most famous for his feelingful melodramas Humoresque (1920), Seventh Heaven (1927), and Street Angel (1928). He made those last two features at Fox while F. W. Murnau was there, and it’s probably not too much to see the brackish mist of Borzage’s 1948 film as reviving the look of the nocturnal countryside scenes of Sunrise (1927).

Some shots might almost be homages to Murnau’s film.

The compositions remind us that the 1940s deep-focus style isn’t far from the wide-angle imagery Murnau pioneered in the silent era. Although Strauss’s novel gives the Borzage film its title, we’re free to imagine Sunrise (in which the moon figures prominently) as a prefiguration of Moonrise, in which we never see the moon rise.

A final thanks to all who have picked up a copy of Reinventing Hollywood. Apart from its arguments, I hope that it steers you toward some new viewing pleasures.

Film rights to The Silent Patient, whose author has an MFA in screenwriting, have been sold to Annapurna and Plan B. Amy Adams is set to star in The Woman in the Window, from Fox 2000.

It seems that The Woman in the Window owes a debt to more than movies. A detailed profile of its author in The New Yorker suggests that exposure to Highsmith’s Ripley novels at an impressionable age can have serious consequences, especially if you wind up among the Manhattan literati.

Robert C. Harvey offers a careful analysis of Eisner’s Spirit story, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” in The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History (University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 178-191. Interestingly, the chapter is titled, “Only in the Comics: Why Cartooning Is Not the Same as Filmmaking.”

The most comprehensive book on Borzage’s career I know is Hervé Dumont’s de luxe edition Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (Cinémathèque Française, 1993). An English translation was published in 2009.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Urk.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Eep. I try to do the film, and its genre, justice in another entry.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Omigosh.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. So I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death: Parsonage Parlor, by Lorie Shaull.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Comic strips and cartoons, Directors: Borzage, Film and other media, Film comments, Film history, Film technique, Hollywood: Artistic traditions |  open printable version

| Comments Off on REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things open printable version

| Comments Off on REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things

Saturday | March 16, 2019

Kristin here:

On February 13, the day after I posted my blog entry, “3D in 2019: Real Dvided?,” I received an email message from Belgian film critic David Vanden Bossche. He had been intrigued enough by my post to investigate the number of 3D screenings on offer in Belgian cinema chains in comparison with “standard” or “premium” 2D screenings. I had found 3D screenings the distinct minority in our local Madison theatres, even early in films’ runs. David found the opposite in Belgium

To extend his investigation, David enlisted his colleague Tim Bouwhuis to analyze the proportions of 3D screenings in the Netherlands.

David and Tim’s resulting online article, “Filmbeleving als Format: A 3D State of the Union,” was posted on March 13 on Enola.be, a film and music site in Flemish. David kindly offered to send me an English translation of the piece. It turned out to be quite intriguing, since 3D in Belgium and the Netherlands is considerably more robust than in the US. I mentioned in my post that areas of the world outside North America have a higher proportion of 3D-equipped screens than we do here. The attention usually focuses on the Chinese market’s enthusiasm for 3D. This enthusiasm is often credited with encouraging Hollywood studios to keep making 3D films despite their waning popularity in North America. But other countries favor 3D as well, and it’s valuable to have an examination of a pair of small European markets.

Our thanks to David and Tim for allowing us to present their article here as a guest post.

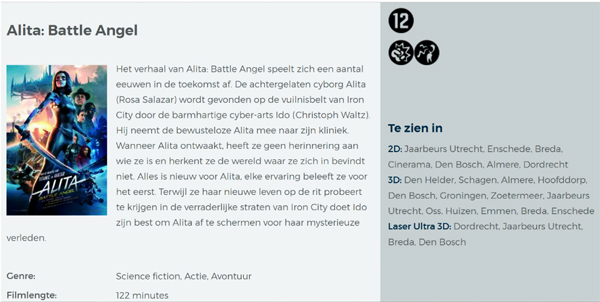

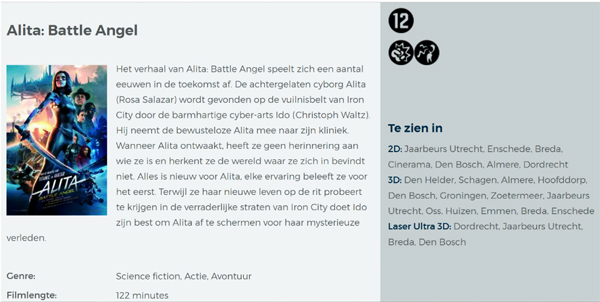

On 12 February, following the American premiere of Alita: Battle Angel, Kristin Thompson posted a new entry, 3D in 2019: Real Dvided? Thompson investigated the state of 3D within the contemporary theatrical environment in the United States. Her conclusion was crystal clear: 3D’s share within American movie screenings has steadily declined in the last decade, when Avatar urged most theatre chains to make the switch to 3D projection. The numbers Thompson presents abundantly show that American multiplexes are less and less inclined to include large numbers of 3D screenings in their programs, and that 3D is losing ground to another ‘premium’ format such as IMAX.

Those findings were intriguing enough suggest a closer look into the Belgian situation. Because that is ultimately a small market, I contacted fellow film critic Tim Bouwhuis, who lives in the Netherlands and could thus provide some information on the particular situation in his home country. Our research allowed us to collect an acceptable amount of material and provide us with numbers that paint a rather different picture than the one to be found in Thompson’s piece. The data we collected show a different evolution for 3D in these two countries and possibly in the whole of Europe. Further research could shed some light on this. Even a limited study, however, offers some possible explanations for these differences. This entry will tackle some of them.

United States: RealDvided

Before dealing with the situation in Belgium and the Netherlands, it is probably a good idea to summarize what Thompson presents in her piece.

Starting with screenings in her hometown Madison, Wisconsin, she observes that 3D’s share in the number of screenings of recent blockbusters is surprisingly limited. Thompson broadens the scope with additional numbers from other cities, concluding that this is definitely not a local issue.

The growth in 3D emerges with the success of Avatar and the consequent peak in 3D earnings in 2010. Since then, 3D’s share of film grosses has been in decline. Production of 3D television sets – a prime feature in store windows just a few years ago – has all but halted. Even if one should exercise some prudence in declaring the death of 3D in a theatrical environment, it is safe to state that its intrusion into the living room has failed spectacularly.

It is remarkable that other ‘premium formats’ (Thompson refers to these as PLF – Premium Large Formats,’ a term we will stick with here) such as IMAX or various “ultra” and “grand” large-screen auditoriums (usually offering extra comfort and superior sound) are gaining in popularity, while 3D is on the decline. That means the public is willing to pay extra for a ‘premium’ – PLF upcharges are as high or higher than those of 3D – and apparently often prefers to pay for PLF rather than for 3D. This process obviously suits the theatres’ economic agenda: a large part of the extra income returns to the distributor and – as Thompson points out – there’s also the extra cost for 3D glasses. The upcharges may also make the visitor less inclined to spend money on food & beverages, a vital source of income for theatres. That means the final balance might be rather negative from the theatre’s point of view in the case of 3D revenues. The fact that PLF’s may net a larger profit thus adds another extra factor working against 3D.

One might expect that in case of Alita the figures would be rather different. The film is produced by James Cameron, one of 3D’s most prolific advocates and arguably one of the few directors – along with Ang Lee, Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Gan Bi and (even) Jean Luc-Godard–who actually tried to explore the true potential of 3D’s formal cinematic language.

The numbers Thompson presents, however, show that even an “event” film such as Alita does not always encourage US theatre owners to schedule more 3D screenings. Thompson points out that there might also be a more practical issue at work here: the clarity of the image is one of the more troublesome issues 3D faces. To solve this, Cameron and Roberto Rodriguez (who took the directing honors when it turned out Cameron was too busy preparing the Avatar sequels) made sure the DCP’s (digital cinema package, used to send movies to theatres since the disappearance of film stock) came with a set of guidelines. These technical complexities, combined with pricey investments and low returns, make for a cocktail that encourages theatres to drastically cut back on the number of 3D screenings.

Belgium: The Kinepolis experience

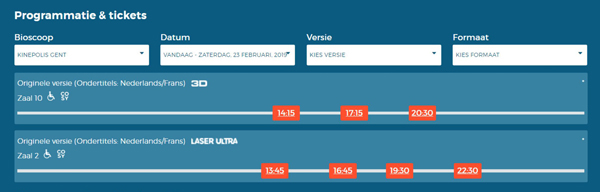

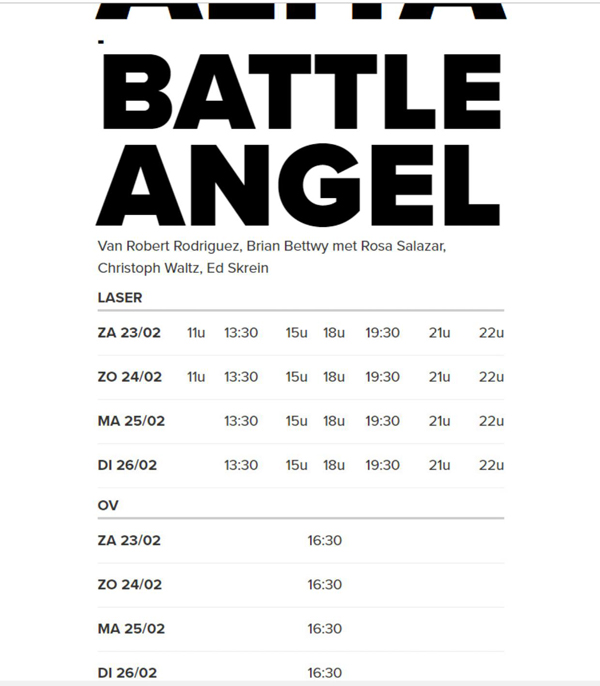

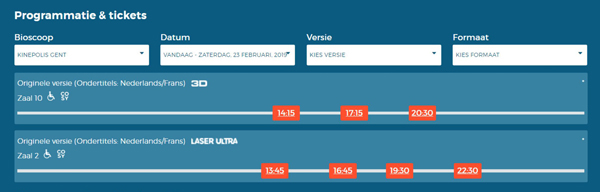

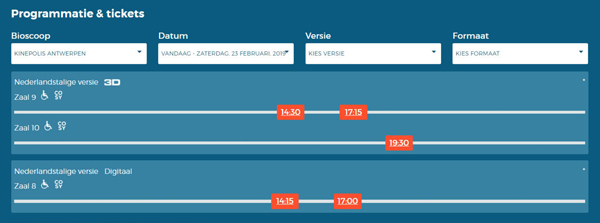

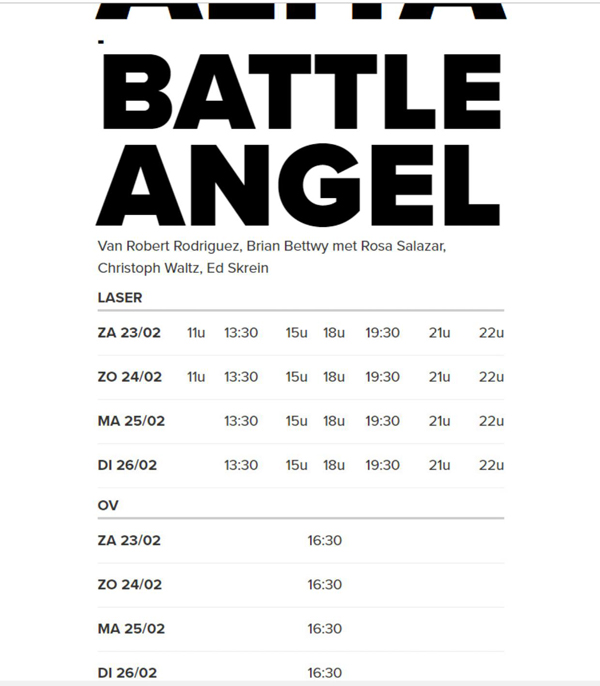

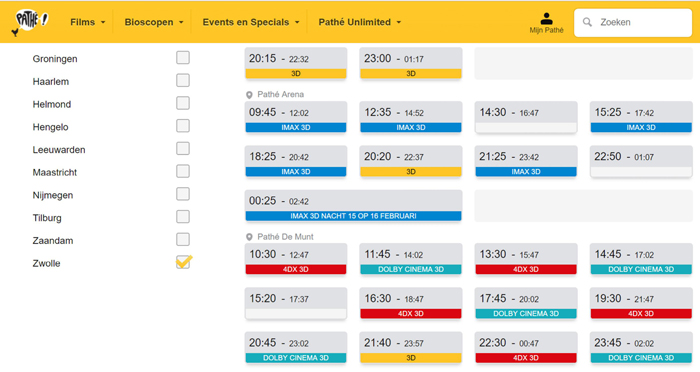

Intrigued by Kristin Thompson’s article, I gathered comparable statistics for Alita in Belgium. See the top image for an ad listing the formats available during the first week of release at Kinepolis Group theatres in Belgium.

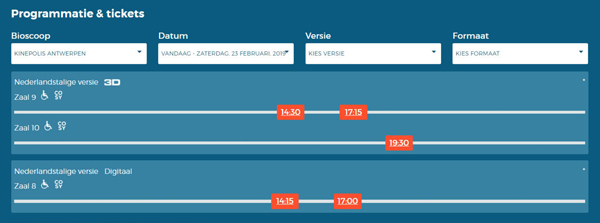

That’s a lot of 3D ! No fewer than four of these six formats integrate 3D into the theatrical experience. Obviously, a film such as Alita is likely to receive such a treatment and definitely during its first week. It is also necessary to look – as Kristin Thompson did – at the relative percentage of 3D versus “standard” 2D screenings. A ten day interval seemed ideal to reassess the situation. Here are schedules for two Kinepolis theatres ten days after the film’s opening.

As it turns out – depending on the Kinepolis theatre one chooses to visit – 3D still makes up between 42 and 67 percent of Alita’s daily screenings. The highest number is reserved for Kinepolis Brussels, with the theatre being the only one equipped with a full-fledged IMAX screen. IMAX as a PLF in Belgium is used exclusively for 3D screenings, save for some very rare exceptions.

As pointed out already, Alita can be regarded as an exceptional production that integrates 3D as part of its raîson d’être and its promotion. Alita’s figures might be exceptional, so looking at a comparable title might be necessary. The Lego Movie 2 made its debut about three weeks later, is also shown in 3D and thus makes for a perfect comparison.

3D’s share is smaller here, but still 40 percent of the screenings are in the 3D format, a number well above the American averages.

Because two titles might still represent a distorted sample, we contacted Kinepolis Group Belgium and asked them to provide us with some material that would allow to have a better general idea about the significance of 3D within their total number of screenings and their profits and the way this share has evolved (or is evolving).

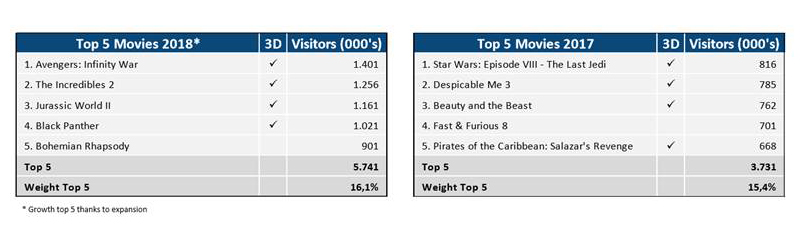

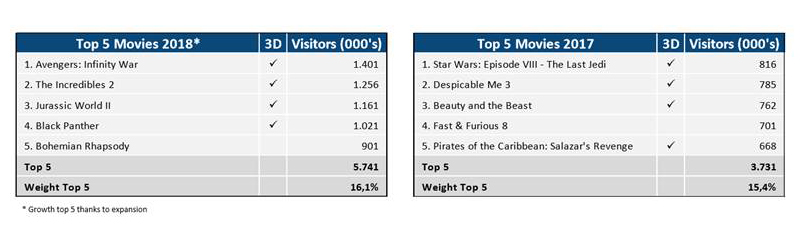

These numbers are clear enough to allow some conclusions. Both in 2017 and 2018, 4 out of 5 of the most popular films for Kinepolis Belgium were 3D movies. 2018’s numbers even show that both the relative share and the absolute numbers (and thus the weight of the top 5 and 3D) are indeed increasing. Obviously that does not mean that every paying visitor opted for 3D (or one of the various combinations of 3D and PLF), but as the general share of 3D screenings for every movie released in this format at Kinepolis theatres in Belgium is situated anywhere between 40 and 60 percent of the total number of screenings. That means this percentage can be applied to these numbers.

The Kinepolis representative pointed out that the percentage of 3D screenings for a movie is determined on the basis of the quality of the 3D imagery and the way the 3D format enhances the viewing experience. Alita is perceived to be a prime candidate for these arguments and thus the number for 3D screenings is very high and at the lower end for The Lego Movie 2. Even if one sticks to the lower end of the scale, however, the importance of 3D screenings within the total number of screenings is still remarkable.

Beyond Kinepolis

All those results lead to a single clear picture: unlike the American situation, 3D is still positions itself as the preferred “premium format” in Belgium. Its impact on the total number of screenings (in Kinepolis theatres) is still very significant and shows no signs of diminishing.

I believe there are a few elements at play to create this situation. One of the first emerges when we take a look at the Alita screenings outside of Kinepolis theatres. Another large chain of theatres, UGC, provides a useful comparison. (Most independent movie houses have not screened Alita). The schedule immediately below is for a UGC cinema in Antwerp, and below that, one in Brussels.

In Antwerp there is not a single 3D screening to be found; in UGC Brussels, there’s just one, while the same day lists 8 standard screenings. The discrepancy between these numbers and the ones at Kinepolis are easily explained: UGC has a very limited number of 3D screens.

Slowly it becomes clear that the very specific situation of the Belgian movie theatre environment is an important factor in all of this.

Kinepolis Group was formed through the joining of two large family companies, the Claeys & Bert Groups. At the start of the 19080s, they began setting up a chain of theatres that no longer consisted of the smaller movie theatres Belgium had known up to that point. Their theatres introduced multiplex to the country. “Decascoop” in Ghent (first 10 screens, with two added later) and the other early Kinepolis theatres benefited from the rise in ticket sales in the early eighties and consolidated their position by being the only theatres around the country able to show box-office hits such as E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial and the “Indiana Jones” trilogy, on multiple screens. 1988 saw the inauguration of Kinepolis Brussels – at that time one of the largest theatres in Europe – along with the first IMAX screen in the country (and most neighbouring countries).

At that time though, IMAX was a used only to screen spectacular documentary films that offered the sensation of flying through the Grand Canyon, diving into the ocean or being in outer space. Production of these films was rather limited. When the audience started to lose interest, Kinepolis halted its programming in 2005, just when the US market was taking its first steps towards IMAX screenings of regular releases. Christopher Nolan’s films were instrumental in the process that eventually turned IMAX into a popular “premium format.”

More or less simultaneously 3D resurfaced. The format enjoyed some popularity during the fifties (Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder comes to mind) and returned in the early eighties, blessing film history with a few horrendous films as Jaws 3D and Friday The Thirteenth – Part III 3D. The more recent revival of 3D gained impetus with the releases of animated films, notably The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005) and was given a boost by U23D (2008). Other animated and concert films followed, but it was Avatar, with its combination of 3D with the latest state-of-the-art special effects technology, that pushed theatre owners to convert their screens to digital projection, the necessary prerequisite for add-on 3D capability. Its huge success started an evolution that promised the full potential of the 3D cinematic language would finally be explored. When Scorsese, Lee, and Godard took up experiments, it even briefly seemed this would actually be true.

In the US, although Cameron’s smash hit dictated the rapid spread of 3D technology, the format still had to face competition from the already established IMAX format. That was not the case in Belgium or the Netherlands. Kinepolis Group – the dominant chain by now – solely promoted 3D, and this position dictated the whole theatrical environment. The IMAX screen reopened in 2016, when 3D was well established as the preferred premium format. IMAX was (and is) used almost entirely for 3D screenings.

It is necessary to include another element here: the exceptionally high projection standards at Kinepolis Group. When John McTiernan came to Brussels in 1988 to launch Die Hard, he claimed that there was probably no better projection of his film to be seen anywhere in the world. Those might have been the words of an overly enthusiastic director, but they illustrate the high technical standards within Kinepolis Group. Other theatre chains were more or less forced to follow suit.

Because quality projection became the standard, any other “premium” format faced a high hurdle when it came to distinguishing itself. “Laser Ultra” already offers an exceptional viewing experience on a very large screen, so further investment had to be justified by something beyond image quality or a larger screen. 3D offered such a distinctive element and extra added value and initially did not face any competition from PLF’s. When that changed, Kinepolis kept promoting 3D, with combinations: “Laser Ultra 3D” and “4DX,” which adds vibrations to the experience.

All of the above means that 3D’s position in the Belgian environment is very different from its position in the US. Obviously Kinepolis also needs to pay the distributors, but a new deal with RealD on the use of 3D glasses consolidates Kinepolis’ position and intensifies their efforts to promote 3D. All of this means that the format will remain popular in Belgium. In this way, Kinepolis Group’s market position also dictates 3D’s standing as the preferred “premium” format in Belgium.

The Netherlands: Experiences & attractions

The Kinepolis Group is also a dominant factor in the Netherlands, which makes comparing the situation in both countries an interesting endeavour. The Netherlands’ theatrical environment has two major chains, Pathé and Kinepolis, both of them part of larger European concerns. Pathé is part of the French group ‘Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé’ – a company that has its roots in the early days of cinema. Pathé owns 28 theatres, spread out over 20 Dutch cities. Kinepolis is a branch of the Belgian company and owns 17 theatres in the Netherlands.

With 21 theatres, “Vue Nederland” also deserves to be mentioned, although their total seating capacity is rather limited and has its main focus on smaller provincial towns.

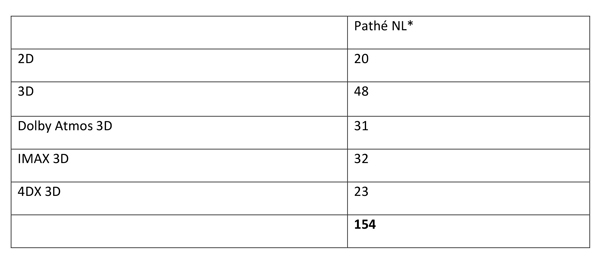

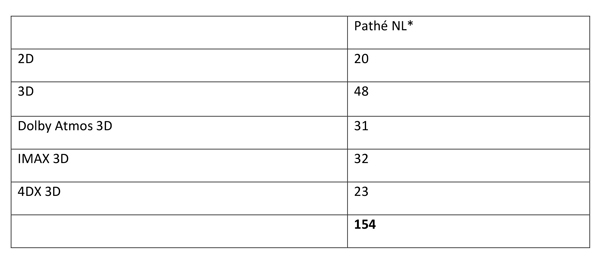

The rise of new technologies, PLFs and “extra” movie attractions such as 4DX, has lead to a situation in which standard screenings have become something of a curiosity in the multiplexes of most major cities. Almost every theatre in a major city boasts 3D, Dolby Atmos or another premium feature. Developments in sound and imagery are promoted: Pathé even distinguishes between Dolby Atmos and Dolby Cinema, with the first emphasizing immersive sound.

Six IMAX screens are spread throughout the country, although most of them would not stand up to a purist’s scrutiny: the largest one – Pathé Arnhem – measures 21×12 metres, whereas a standard IMAX screen is supposed to be at least 22x16m. The Dutch IMAX venues pale in comparison to Brussels’ enormous 27.6 x 19.3 screen.

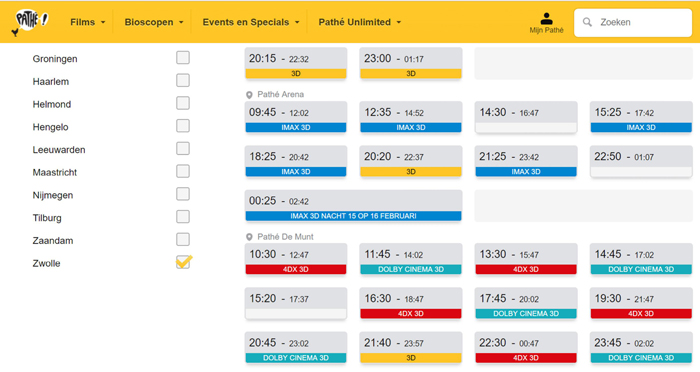

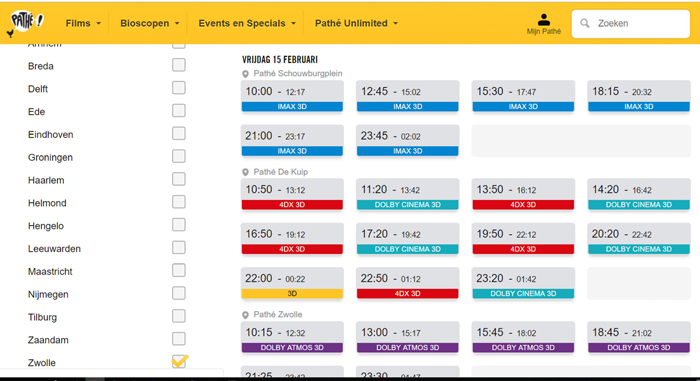

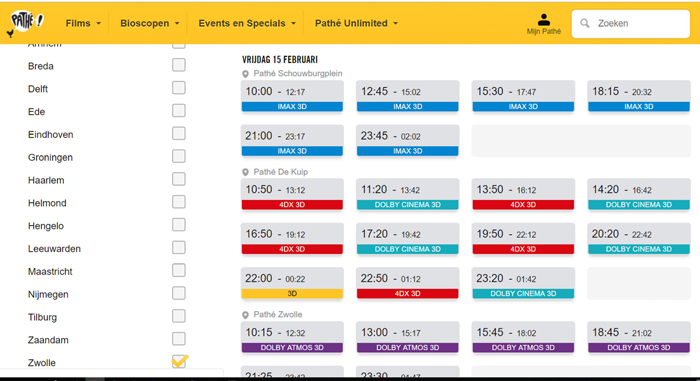

This variety of screens, systems, and venues makes it difficult to get a good grip on the partition of different formats, so once again we turned to specific Alita screenings available on February 2, 2019 :

At first glance, standard 2D and 3D screenings are balanced by premium screenings. That perception changes, when we take into account that only 5 out of 25 theatres feature 4DX, 5 offer Dolby Atmos 3D and 6 offer IMAX. That means that in some theatres it has become all but impossible to see a standard 2D screening.

The most important factor here is the fact that theatres that offer 4DX/Dolby Atmos 3D/IMAX, focus almost entirely on these formats. Those theatres are usually situated in larger cities, thus rendering it almost impossible to see a standard screening there. Amsterdam/Rotterdam (see above and below) are prime examples: out of 44 combined screenings only three of them are standard screenings. In Scheveningen, Maatsricht or Eindhoven there are no standard screenings to be found at all on the same day.

Most theatres are still located in smaller cities, and a general overview would thus suggest a rather balanced field of standard and 3D screenings. But even in those smaller venues – that do not offer the extra attractions 4DX, Dolby Atmos 3D or IMAX, the 3D screenings still outnumber standard screenings (see below)

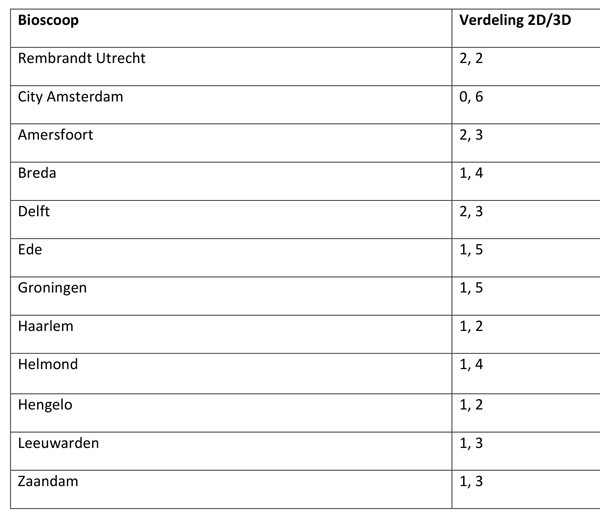

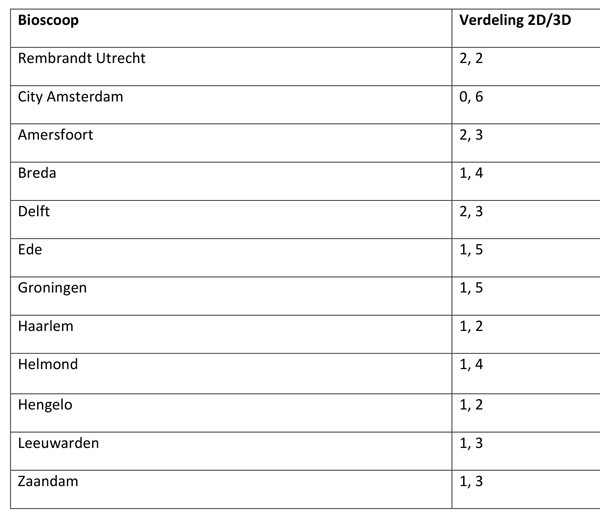

3D vs 2D in theatres without 4DX, Dolby Atmos and/orIMAX as of February 15, 2019:

With 1 out of 3/3/4 , it is clear that 3D screenings are dominant in Pathé theatres. Even daytime screenings on weekdays are 3D, which relegates standard 2D screenings to the position of a rarity.

Kinepolis’ available number of formats in the Netherlands is more limited than in Belgium. Neither IMAX nor 4DX is an option here. For Alita that results in:

The Vue chain competes with Kinepolis and Pathé in offering DX theatres that combine Dolby Atmos with superior projection technology. As in Belgium, the dominant chain sets the technical standard. A select number of theatres offers D-Box chairs that move with the action on screen. The American film critic Jeffrey Wells describes D-Box chairs as “4 DX’s less dynamic cousin.” (D-Box is Canadian in origin, while 4DX is South Korean).

Pathé, Vue and Kinepolis promote their different PLFs in exactly the same way, using “experience” and “immersion” as unique selling propositions. With 4DX the movements and effects start competing with the images for the viewer’s attention, returning the cinematic experience in a ironic way to its attraction-based origins when it was something to be experienced at fairgrounds and other shows.

In sum, the Dutch theatrical environment resembles the Belgian. A high technical standard has become the zero-line for movie screenings and 3D has penetrated the market to such an extent that it is no longer perceived as being a “premium” format, which leads to a set of various attraction-based formats that try to justify the extra cost.

At this point Dolby Atmos, Imax, and 4DX are still perceived as novelties, but it is likely that exhibitors will need additional attractions in years to come. Rising admissions for PLFs and anything “premium” suggest that visitors are constantly looking for more immersive experiences (according to the “Dutch Foundation for Film Research” in their 2018 yearly review). The number of available PLFs has significantly risen in the last few years and as long as the dominant chains continue to invest in these formats, others will follow suit. Kinepolis and Pathé set the standard, competing chains adapt.

Whether or not the public is actually asking for these technologies remains a topic open to discussion. One could claim the public merely adapts to the industries’ innovations. Still, there is no denying that PLFs turn a large profit. In Pathé Rotterdam the regular ticket price for PLF is 18 euros, while a standard screening will cost you 11 euros. Despite the cut that needs to return to the distributors, the cost for 3D glasses, and the “hardware” investments, 3D in all its forms is dominant when it comes to movie screenings in the Netherlands. The late entry of IMAX into this environment (as in Belgium and contrary to the US) meant 3D had little or no competition and consolidated its position as the preferred “premium” format.

These conclusions to come with some nuances. The Dutch part of this piece limits itself to one title and three dominant chains. Independent movie theatres were not addressed and obviously Alita: Battle Angel has some standard screenings outside of the major theatre chains. There is enough conclusive evidence, however, to support the claim that standard screenings have all but vanished in the larger cities.

A publicity image for Kinepolis, Brussels.

Posted in 3D, Film comments, Film technology, PANDORA'S DIGITAL BOX: The Blog Series |  open printable version

| Comments Off on The movie experience as format: A 3D state of the union open printable version

| Comments Off on The movie experience as format: A 3D state of the union

Sunday | March 10, 2019

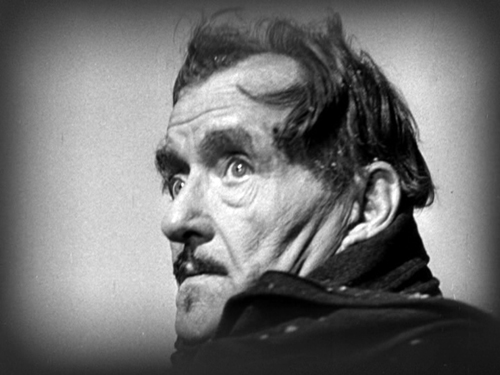

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). Production still from lost scene.

DB here:

This is the third blog entry amplifying on the paperback edition of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. This mini-series tries to enhance the book’s arguments by taking into account books and DVDs that have come out since the hardback publication in 2017. (Previous entries are here and here.) Today I want to talk about what T. S. Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent” in a realm Eliot would disdain: American studio cinema.

Curtiz, pronounced Cur-tess

Noah’s Ark (1928).

Reinventing Hollywood offers itself as an alternative to two major ways of understanding the films of a period. One angle is to see creativity flowing from gifted filmmakers. The story often concentrates on how they have to struggle against the constraints of the film industry. In the Forties, Orson Welles would be a prime instance, though Preston Sturges and others could also be invoked. Without denying the talent and originality of key filmmakers, and without neglecting the stubborn ignorance of many executives, I wanted to show that in many ways creativity can be enabled by the conditions of the industry.

Genre is an obvious instance. Without the Western, where would John Ford be? The musical brought out the gifts of Minnelli and Donen, just as the crime film spurred Huston and Anthony Mann. I wanted to suggest that filmmakers were challenged to work with other normative factors than genre—factors centering on how stories were told. Writers and directors collectively amassed a menu of narrative options, from flashbacks to voice-overs, that got quite refined in the course of a dozen years or so.

Some sympathetic readers have considered the book anti-auteurist because I emphasize those pooled resources that any filmmaker, weak or strong, could draw upon. To some extent, that’s right: stretches of the book resemble “art history without names.” Tony Rayns warned readers that they should read Reinventing Hollywood with Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide at hand.

Not a bad idea. A single paragraph compares A Child Is Born (1940), One Crowded Night (1940), Busses Roar (1942) and Dial 1119 (1950). None of them is exactly a lustrous classic, and I didn’t mention the directors or the screenwriters. My main point is that these films play out variants of the Grand Hotel plot, and they show how even artisans can take the opportunity to revamp current norms.

So for my project, creators of whatever rank matter. In the course of my research, it struck me that three “creative producers”–Hal Wallis, David O. Selznick, and Darryl F. Zanuck–are as important as many directors. The same goes for screenwriters, such as Casey Robinson, Vera Caspary, and Ben Hecht. And now that we have biographies of Victor Fleming and William Wellman, we’re starting to understand the importance of skilled directorial artisans. I’ll take even so-so craftsmen (and craftwomen) if they can teach us secrets of Hollywood carpentry. Charles Lang and Walter Lang are no Fritz Lang, but they made more popular films, and we can study the ways they instantiate filmmaking norms. So for my project, creators of whatever rank matter. In the course of my research, it struck me that three “creative producers”–Hal Wallis, David O. Selznick, and Darryl F. Zanuck–are as important as many directors. The same goes for screenwriters, such as Casey Robinson, Vera Caspary, and Ben Hecht. And now that we have biographies of Victor Fleming and William Wellman, we’re starting to understand the importance of skilled directorial artisans. I’ll take even so-so craftsmen (and craftwomen) if they can teach us secrets of Hollywood carpentry. Charles Lang and Walter Lang are no Fritz Lang, but they made more popular films, and we can study the ways they instantiate filmmaking norms.

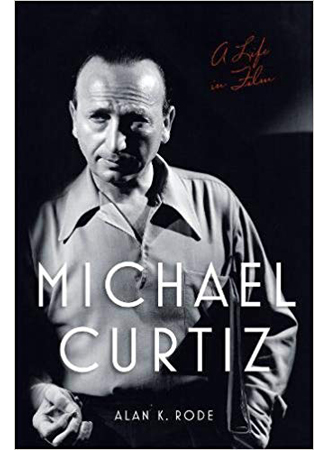

Then there’s Michael Curtiz.

Andrew Sarris claimed that “Curtiz reflected the strengths and weaknesses of the studio system,” and most writers have agreed. Although Curtiz is mentioned by name only twice in Reinventing Hollywood, I draw examples from ten of his films, from Four Daughters (1938) to Young Man with a Horn (1950). I devote most space to Passage to Marseille (1944). Mildred Pierce (1945) is absolutely central to the book’s arguments, but as I’ve written about it before, both in print and online, I didn’t rehash my argument in the book.

Which is to say, I guess, that Curtiz exemplifies what I was analyzing. He was a master craftsman who has a lot to teach us about norms, both inside and outside Hollywood.

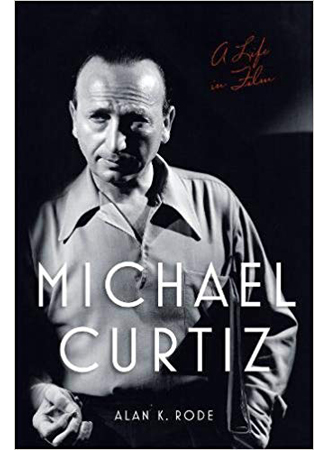

Alan K. Rode’s biography, Michael Curtiz: A Life in Movies, focuses on the man and his accomplishments, and it paints a vivid portrait of a director of intense creative and sexual appetites. He also liked polo. Drawing on memos, production records, and memoirs published and unpublished, Rode provides brisk, telling background on dozens of films. He dwells, as you’d expect on the milestones: Noah’s Ark, the early 30s horror films like Dr. X, Angels with Dirty Faces, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Casablanca, and the Flynn vehicles. But he doesn’t neglect the fleet-footed programmers like The Kennel Murder Case (1933) and The Case of the Curious Bride (1935), projects enlivened with fancy angles, propulsive pace, and bold tracking shots.

On-the-set anecdotes keep things lively. Rode is careful to debunk some of the most famous stories, but he leaves a lot of good ones in. His conversational style is likewise engaging. He compares Peter Lorre to “a sinister kewpie doll” and calls Alexis Smith lissome, using a word I had forgotten exists. Although Rode isn’t as interested in the questions I pursued, his book set me thinking about creativity in the studio system. Specifically, we can broaden our view of Curtiz’s career, which ran from 1912 to 1962, and see it as encapsulating some major trends in commercial entertainment cinema, inside Hollywood and out.

Starting well before DeMille, Ford, Hitchcock, Hawks, Walsh, and other Hollywood auteurs, he was initiated into the standard tableau style of the 1910s. Fairly distant shots in long takes relied on deep sets, staging and performance. Cutting was used principally to shift the scene, show adjacent locales, or occasionally enlarge a detail. The Undesirable of 1914 (available in a stunning restoration distributed by Olive) shows fairly orthodox choreography of figures in depth and across the frame, with foreground figures masking irrelevant background action.

Apart from Lubitsch and DeMille, most of the directors who had long careers in the studio system didn’t come out of tableau cinema. They began by practicing the rapid editing and close-up framings that emerged in America in the mid-1910s. Curtiz was more or less up to speed with them in his stupendous Viennese production Sodom und Gomorrha (1922, available on a well-restored DVD version). He breaks up vast shots with axial cuts, close-ups, and occasional reverse angles. This nutty film, surely one of the biggest productions of the day, used kitschy modern sets for the contemporary story, expressionist ones (with cadaverous jailers) for dreams, and gigantic pseudohistorical ones for Biblical bacchanals.

His first American film, The Third Degree (1926), tries to bring into Hollywood some fashionable European stylization. Curtiz showcases flashy camera movements, rapid rack-focusing, swift montage, and distorted subjectivity reminiscent of French Impressionist cinema. The specific reference is Dupont’s Variety (1925). Curtiz’s tightrope shots mimic Dupont’s trapeze angles, and prismatic superimpositions of eyes during the cops’ third degree recall the swirl of the spectators’ eyes in Variety.

When a detective drops down to investigate a clue, Curtiz doesn’t hesitate to cut to a skewed view framed by the arm and leg of his crouching colleague.

Much of Noah’s Ark (1928) uses standard silent-film continuity style, although Hal Mohr’s lighting sparkles even more than in The Third Degree. Curtiz’s opening montage relies on wide-angle compositionssof a type resembling images in Murnau’s late silent pictures. Here we dissolve from Biblical worshippers of gold to modern stockbrokers, and the dense packing of figures recalls William Cameron Menzies’ work of the same period.

But Curtiz’s most flamboyant effects are reserved for the spectacle, especially in the preposterously vast flood scenes with devastation that recalls the rain of fire in Sodom und Gomorrha.

In his sound pictures Curtiz was less outré, but he never lost his taste for momentary flourishes. Anybody who starts a film called The Keyhole (1933) by moving the camera through a keyhole gets points from me.

Curtiz made his name as a master of crowd effects, and he didn’t shrink from handling groups in tight interiors. A hotel-suite party in Kid Galahad (1937) runs thirteen minutes and is packed with movement. The first shot starts on a phonograph, two abandoned drinks, and a carelessly smoldering cigarette–details indicating a wild party, and setting up the importance of serving drinks in the scene to come. Tilt up to a mirror that hints at a space we’ll soon visit.

The next shot launches a leftward track across two rooms, motivated by a damsel’s wild shimmying. People are packed into the foreground and distance. In the next room the dancing woman carries us to card players before we settle on the fight promoter played by Edward G. Robinson, who calmly gets a haircut amid all the revelry. (After all, the party has lasted three days.)

As these Kid Galahad shots show, Curtiz favored low angles and moderately wide-angle lenses to jam his figures together. In the party scene, he multiplies setups freely, almost never repeating one exactly. (Compare the slightly different framings of the second and third image.) The confrontation of two prizefight gangs is played out in a tricky mirror shot.

By comparison, W. S. Van Dyke’s handling of an apartment party in The Thin Man (1934) looks timid.

Watch Four Daughters (1938) and Four Wives (1939) to see how adroitly you can choreograph a big bunch of people strewn around a parlor. In the first film, Curtiz never lets us forget the defensive outsider Mickey (John Garfield), disturbed by this loving household and shielding himself behind the piano. Some might say that Curtiz’s use of “distant depth” is less heavy-handed than Welles’ in-your-face foregrounds in Kane, three years later.

Rode shows how Curtiz managed to control his films while shooting. From the start, in The Third Degree, he freely added scenes to the script. Thereafter, producer Hal Wallis railed at his “overshooting” with more angles than most directors would use, and he added props and actors without permission. Hawks, Hitchcock, and Ford would work uncredited on the screenplay, but Curtiz simply changed the script on the fly. As he gained more authority, he prepared new dialogue and business at night with his wife Bess Meredith.

Often over budget and schedule, constantly berated by his bosses, Curtiz got away with it all because the films were usually successful and critically acclaimed. Besides, the complaints usually came too late; he was already at work on the next movie. In some years he turned out six features. He’s a good example of a how a vigorous Hollywood artisan could leverage the system through both craft and craftiness.

Wellesapoppin’

I can’t foreswear auteurs altogether. Reinventing Hollywood does spare some time for Preston Sturges, Mankiewicz, Hitchcock, and a few others.

Notable among those is Orson Welles, who threads through my story. Citizen Kane helped popularize flashback narrative for A-pictures, and I argue that its use of the device blended several options that had floated around in the years just before. In the chapter on Hollywood’s efforts to interpret its own traditions, Welles and Sturges come forth as proto-film-geeks citing film history. The Magnificent Ambersons is imbued with a nostalgia for silent films. There’s the edge-vignetting on the early scenes (above), the famous iris that closes the snow idyll, the final credits showing the players more or less addressing the viewer, and the very geeky posters I illustrate in this entry and those leading up to it. The now-lost scene on the veranda with George, Aunt Fanny, and Isabel, shown at the top of today’s entry, included a vision of Lucy appearing to George “in transparency (the shadowy ghost figure from the silents).”

Most extensively, Reinventing discusses Welles and Hitchcock as directors who shaped 1940s storytelling conventions and then had to respond to others’ use of them. I’m again trying to set auteurist claims in a wider context, that of a flourishing ecosystem of creative choices. Just as important, both directors continued using 1940s strategies throughout their later careers. Welles’ importation of Theatricalist stage theory into film, along with his reliance on flashbacks, voice-over, and embedded stories, are central to his later work.

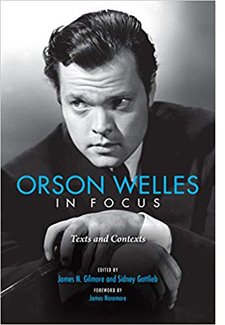

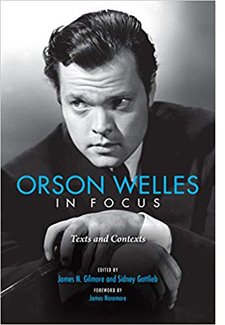

Research on Welles never stops, and so I’m happy to welcome new developments. There’s of course the rehabilitation of The Other Side of the Wind, which features flashback construction, films-within-the-film, voice-over, and other preferred Wellesian tactics. Now we also have Orson Welles in Focus, edited by James N. Gilmore and Sidney Gottlieb, with an introduction by James Naremore. Research on Welles never stops, and so I’m happy to welcome new developments. There’s of course the rehabilitation of The Other Side of the Wind, which features flashback construction, films-within-the-film, voice-over, and other preferred Wellesian tactics. Now we also have Orson Welles in Focus, edited by James N. Gilmore and Sidney Gottlieb, with an introduction by James Naremore.

It’s a set of papers from a 2015 centenary conference on Welles at Indiana University, and they’re all stimulating and wide-ranging. Margaret Rippy reveals the roles of Asadata Dafora and Abdul Assen in collaborating with Welles on the 1936 Macbeth, while Catherine L. Benamou, an expert on It’s All True, shows how the episodes open up different options for transcultural critique in the documentary mode. Welles’ 1946 Broadway musical Around the World gets careful consideration by Vincent Longo, who intriguingly relates it to Bazin’s contemporaneous reflections on theatre and film. François Thomas incisively exposes the financial and legal tangles around Mr. Arkadin (1955).

Welles the fighting liberal gets important attention in two essays. Sidney Gottlieb, who has been assiduously collecting Welles’ writings for years, surveys the director’s journalism for The New York Post. Similarly, James N. Gilmore scrutinizes Welles’s 1946 correspondence, where he continued to denounce racism and antisemitism.

The two essays most relevant to Reinventing Hollywood touch on Welles as cinephile and Welles as storyteller. Matthew Solomon provides a detailed account of Welles’ love of “old-time movies.” Solomon is especially enlightening on Welles’s fondness for citing films made before his birth, as if there he found the most powerful images of “pastnesss.” Shawn Vancour traces how Welles’ use of first-person narration in the 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast develops norms of radio storytelling that were emerging at the moment. Using manuals for radio scriptwriting, Shawn shows that Welles’ shifts between present and past, first-person and third-person narration became common in the years that followed. Both of these essays enrich points I tried to make in my book.

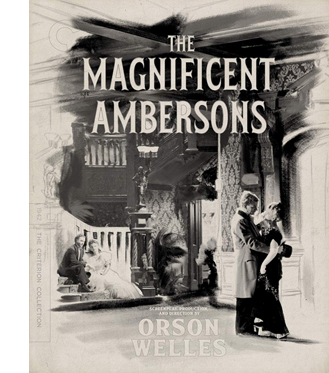

Then there’s that triumph of modern DVD publishing, Criterion’s long-awaited version of The Magnificent Ambersons. A gorgeous transfer is accompanied by a booklet of discerning essays by Molly Haskell, Luc Sante, Geoffrey O’Brien, Welles himself (on his father), and Farran Smith Nehme (on Welles’ speaking voice, which definitely deserves analysis).

On the AV bonus front, producer Issa Clubb has wisely retained many items that made the company’s pioneering 1986 laserdisc release a demo of what that format could deliver. We get Robert Carringer’s sensitive voice-over commentary, an audio recording of Welles’ radio adaptation of Tarkington’s novel, some interview bits of Welles discussing the film, and the remaining clips from Pampered Youth (1925), an earlier adaptation of the book. On the AV bonus front, producer Issa Clubb has wisely retained many items that made the company’s pioneering 1986 laserdisc release a demo of what that format could deliver. We get Robert Carringer’s sensitive voice-over commentary, an audio recording of Welles’ radio adaptation of Tarkington’s novel, some interview bits of Welles discussing the film, and the remaining clips from Pampered Youth (1925), an earlier adaptation of the book.

We’ve unfortunately lost Carringer’s visual essay on the film’s style, and Welles’ storyboards and shooting script, rendered in that single-frame technology that made CAV discs clunkily hypnotic. But the new material more than compensates. Clubb has turned a treasure chest into a cornucopia.

We get a second Mercury Theatre radio play, this one based on Tarkington’s Seventeen. A second audio commentary track, featuring James Naremore and Jonathan Rosenbaum, finds illuminating new things to say about this all-but-masterpiece. I also learned an enormous amount from François Thomas’s essay on the mix of cinematography styles in the film, which he tracks through daily production reports. Stanley Cortez, whom Kristin and I once interviewed across two fruitless hours, was only one of several DPs working on the movie.

Christopher Husted shows how the careful parallel scenes of the full-length version received delicate scoring by Bernard Herrmann, who took his name off the film when RKO recut it. A panoply of interviews with Welles, Simon Callow, Peter Bogdanovich, and Joseph McBride is sure to interest old fans and newcomers. The story of Ambersons will never grow old, and we’ve made remarkable progress in understanding its intricacies.

Magnificent ruin

Welles went to Brazil at the behest of the US government, to make a film supporting the “Good Neighbor” policy toward South America. Shooting on Ambersons finished in January 1942, and Welles left his notes with Robert Wise, the film editor who was to oversee postproduction. Wise was to bring a draft result to Welles in Rio, where they would fine-tune it. But wartime travel restrictions, and perhaps RKO’s reluctance, kept Wise at home.

In the trade papers, RKO claimed that Welles was fully engaged in finishing and cutting Ambersons in Rio. “Orson Welles So Tireless, Cuts ‘Ambersons’ by Wireless,” ran a rhyming headline in Hollywood Reporter. The first sneak preview was reported as being 2 1/2 hours, a second around two hours, but Robert Carringer in his authoritative study, The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, has suggested on the basis of production correspondence that the first preview version probably ran about 101 minutes, the second around 117.

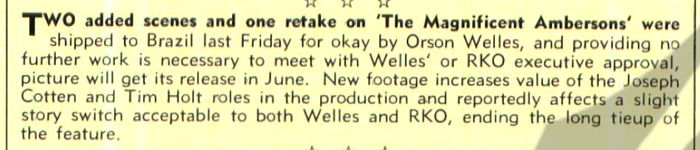

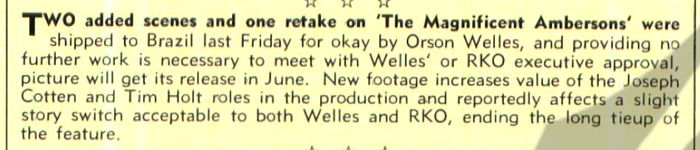

Reacting to harsh audience criticism, Welles’ associates at RKO decided that film had to be cut and new scenes had to be shot. Joe McBride’s Criterion interview explains that the studio had lost faith in the project and was ignoring the detailed instructions that Welles sent by cable. By this time, because of contract renegotiations after Kane, Welles no longer had right of final cut. But RKO continued to claim, as in this 29 April Variety story, that the director was fully on board.

Actually, two weeks earlier, Carringer tells us, studio head George Schaefer had transferred authority over the final cut to Wise.

The studio announced that changes were being made, though they seem never to have been specified. Press releases built on Hollywood’s continuing dislike of the boy genius. One story was put out that Welles had demanded that Joseph Cotten send him “weekly shipments of Chinese dishes” by air, as if defying wartime privation.

Ambersons had been planned as a “special” alongside other big RKO-distributed titles (The Pride of the Yankees, Bambi), and aiming at an Easter release. Instead, it was eventually absorbed into a block of titles, which was the standard way of packaging A and B pictures together. The recutting pushed the film’s release into the doldrum days of summer, the graveyard for second-tier product. After a July debut in Los Angeles, it didn’t appear in New York until August. Box office was initially good in some venues, but nothing compared to the big hits of 1942: Mrs. Miniver ($5.4 million in rentals), Yankee Doodle Dandy, Random Harvest, Reap the Wild Wind, Holiday Inn, The Road to Morocco, The Pride of the Yankees, and Wake Island.

A quick sampling of newspapers around the country shows that into the fall, the film sometimes appeared alone on a program (even in La Crosse, Wisconsin). Elsewhere it seems to have been the top of a double bill that includes such items as Syncopation, Her Cardboard Lover, Little Tokyo, USA, Ellery Queen’s Desperate Chance, and most notoriously, Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost.

Was it Ambersons that sank Welles’ future? Some have said so. According to a 1952 record of RKO profits and losses across the studio’s history, the film was claimed to have lost $620,000. Before that, only Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) was registered as a bigger flop for the studio.

McBride’s interview explains that the Amberson debacle was part of a larger effort to undermine Welles. RKO was in turmoil, having lost many key executives. Building off his book What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career, Joe suggests that after the problems with Ambersons and Welles’ departure for Rio, factional fights broke out among the suits. Schaefer, attacked for the disappointing box office of Kane, was caught between defending Welles and trying to save his job by cutting Ambersons.

Executives worked to sabotage Welles’ next project as well. One powerful piece of evidence that Joe discovered shows that RKO lied to Welles about the budget for It’s All True, so they could attack him for imaginary overruns. In his interview and book Joe reveals that Welles was under budget by over $440,000 when he was fired for going over budget.

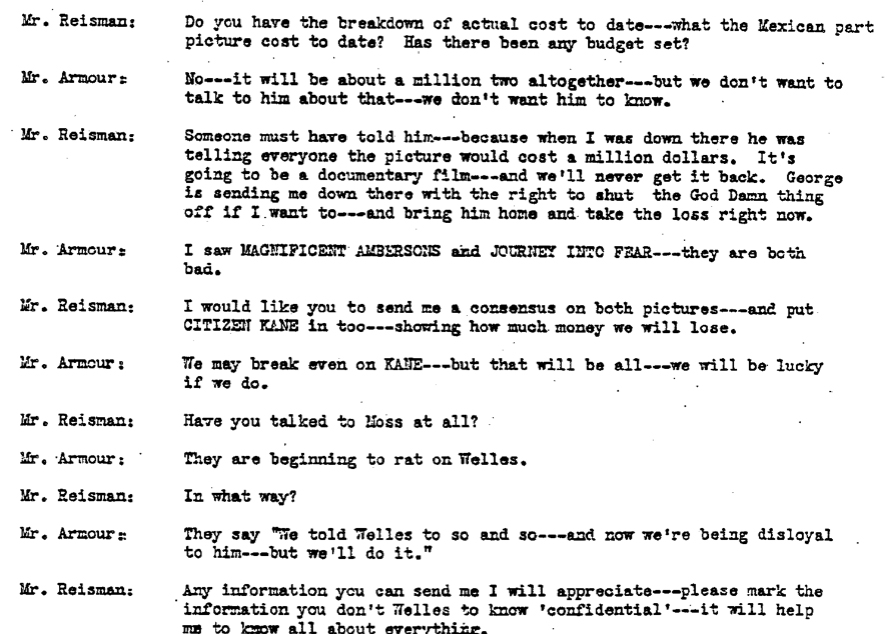

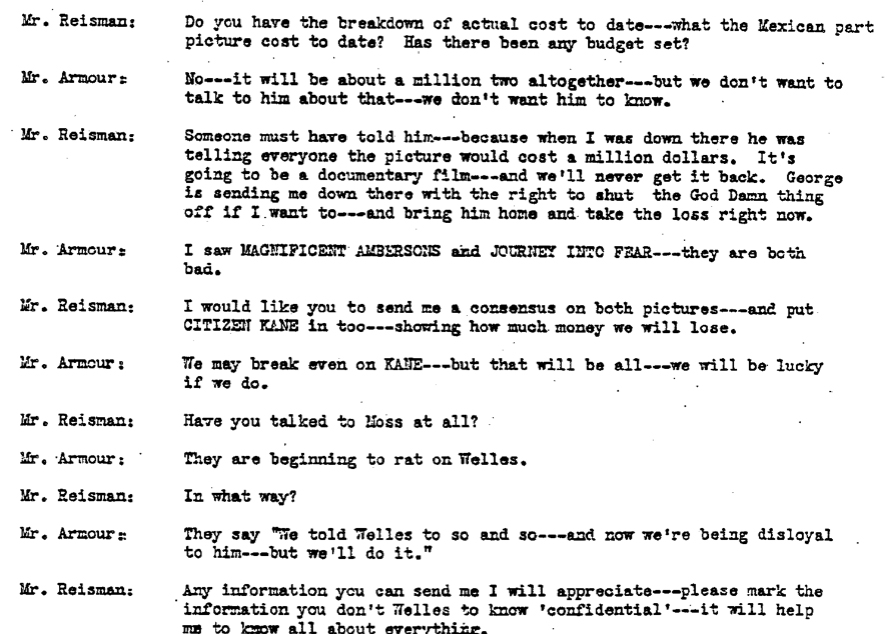

Joe also cites a damning transcript of an April 1942 conversation between two RKO executives, Phil Reisman and Reginald Armour, who conspired to keep information from Welles.

The reference is to Jack Moss, Welles’ business manager. Reisman and Armour go on to discuss the possibility of getting Welles drafted and speculate what could be salvaged from It’s All True–perhaps a couple of shorts?–and Armour adds: “George will lose his job out of this.” Schaefer was fired from RKO at the end of June.

Soon after the release of Ambersons in July, Welles’ Mercury unit was moved off the RKO lot. Welles returned from Rio still hoping to rescue It’s All True, but soon he would become a director for hire.

The Criterion disc release reminds us of how original Welles was in his storytelling strategies. Reinventing Hollywood argues that in Ambersons Welles found a fresh way way to treat time shifts. He keeps major action offscreen and prior to the scene we see, so that each character becomes a narrator reporting action to others, without benefit of flashbacks. The famous scene of Fanny and George in the kitchen is a good example, as he tells her that Eugene joined their trip to the college commencement.

There are many other examples; nearly every scene’s dialogue reaches back to the recent or distant past.

This rather literary strategy of replacing showing by telling echoes the narrative strategies of Henry James and Joseph Conrad–the latter a writer whose work influenced Welles strongly. In the 1940s Hollywood context, all this recounting in retrospect constitutes a “knight’s move,” a swerving response to the emerging flashback conventions of the time. I believe that Welles rethought his radio brand, “First Person Singular,” for Ambersons.

Welles’ original ending, which shows Eugene and Fanny reminiscing in her boarding house, was in keeping with this strategy of suppression. Eugene recounts the resolution we haven’t seen: the reunion of George and Lucy, and George’s contrite reconciliation with Eugene. “We shook hands.” Ending with George and Lucy, the new generation, would have been conventionally upbeat, but Welles wanted to linger on the old people–one the automobile pioneer, the harbinger of dubious progress, and the other a castaway of plutocratic pride and self-absorption.

The reshot scene in the hospital corridor exudes a hollow cheerfulness that generations of critics have rightly found a travesty.

This hospital shot lacks the pathos of Welles’ scene, in which a numb, impoverished Fanny is left alone while Eugene drives back into the grimy city. Still, at least the shot preserves much of the original dialogue and it sustains a narration that keeps crucial events (George’s apology and the lovers’ reunion) offscreen and in the past. To the end, action is replaced by reaction–or rather, by reflection.

My title today is a bit misleading. The artist/artisan distinction is fuzzy. Curtiz and Welles are both. The difference might come down to this: The creators we call artisans are adept at solving problems set by tradition or their contemporaries. But those we deem artists think up new problems and solve them with aplomb. They may even set themselves problems that seem ridiculously constraining (such as Ozu’s decision about low camera height). In any case, we need to recognize craft in any medium, because that helps us appreciate achievement of every sort.

I owe a big debt to Joseph McBride for his careful checking of earlier drafts of the Welles section of this entry. His What Ever Happened to Orson Welles is an indispensable guide to the director’s career. Any mistakes or misjudgments that remain in this entry are my doing. Thanks as well to Eric Hoyt for help on RKO financial information.

Joe also points out that Simon Callow’s Criterion interview contradicts other researchers’ findings about Welles’ calls and cables from Brazil. In addition, I wonder whether Rode’s citations of the Curtiz films’ grosses shouldn’t be called their rentals–that is, the chunk of the gross box-office receipts returned to the studio. For example, he lists Casablanca‘s grosses as being $$4.496 million. This is close to Variety‘s figure of $4.145 million for the film’s rentals. See Lawrence Coh, “All-Time Film Rental Champs,” Variety (24 February 1992), 164. Typically a picture’s rentals were about half of its gross.

Patrick Keating’s new book The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood calls the kind of tracking shot in Kid Galahad the “follow and switch.” He has much to say about Curtiz’s work in his fascinating account of how Hollywood filmmakers thought about and deployed the moving camera.

Curtiz would likely have seen Dupont’s Variety during his stay in Austria, or even in the US in 1926; it played Los Angeles in June and New York in July. Curtiz arrived in the US on 6 June 1926, and The Third Degree was released on 26 December. As Rode points out (p. 77), the trade paper Variety saw an affinity between Curtiz’s film and Dupont’s, though the reviewer scoffed at the “trick camera stuff” and “freak shots” (5 January 1927, p. 17).

I consider Casablanca in this entry, which ties in both to Reinventing and to Pauline Lampert’s podcast Flixwise. My fullest discussion of Ambersons online is here; the section in Reinventing is somewhat different. On Welles the silent-era cinephile, this entry on his centenary is also relevant, as is this later one.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Horrible.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Duh. I try to do the film, and its genre, justice in another entry.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” What was I thinking?

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. So I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

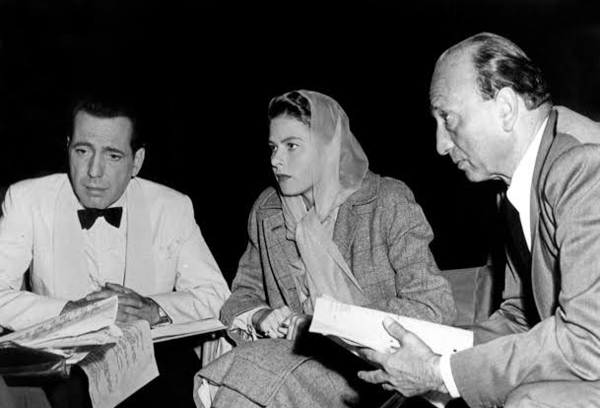

On the set of Casablanca.

Posted in Directors: Curtiz, Directors: Welles, Film comments, Film technique: Cinematography, Film technique: Staging |  open printable version

| Comments Off on REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Artisans and artistry open printable version

| Comments Off on REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Artisans and artistry

Saturday | March 2, 2019

Happy Death Day (2017).

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted. I hope all these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

The first entry in this series is here.

Seeing Happy Death Day 2U reminded me of one of the central arguments of Reinventing. But before I get to that, let me talk about English drama of the years 1660-1710. No, really.

500 plays and more

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.” In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

Hume’s method was simple and drastic. He read all of the preserved plays publicly performed in London between 1660 and 1710. Along with revivals, pageants, translations, and adaptations, there were about five hundred “new” plays, and these he concentrated on. They included famous ones like Marriage à la Mode and The Way of the World, as well as many obscure pieces.

The result was The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1976). Its first part surveys the conventions and formulas found in subgenres of comic and serious drama (sentimental romance, horror tragedy, and many others). In the second part Rob traces the development of these types across the period.