Friday | December 21, 2018

True Stories.

Jeff Smith is no stranger to this blogsite. He has written several entries, some based upon his Criterion Collection commentaries for FilmStruck, others on topics related to film sound and scoring. Here he brings his massive expertise to bear on the music of True Stories, newly available in a 4K transfer from Criterion.–DB

Jeff here:

As promised, this is a follow-up blog to David’s discussion of True Stories and its collage of tabloid culture, kitsch, Performance Art, Robert Wilson, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, and Our Town. At least some of these connections also characterize the New York music scene in the 1970s from which Talking Heads emerged. Buoyed by the energy of punk and New Wave, Byrne had long straddled the boundaries between mass culture and the avant garde.

As before, Andy Warhol serves as something of a role model. Besides designing album covers for mainstream pop performers, such as the Rolling Stones, Billy Squier, and Diana Ross, Warhol also served as the nominal producer of The Velvet Underground & Nico. The artist himself is also the subject of David Bowie’s “Andy Warhol” from Hunky Dory and Lou Reed’s “Andy’s Chest,” an outtake that eventually surfaced on VU, the 1985 compilation of Velvet Underground miscellany.

Working in the opposite direction, Byrne and company’s connections to the Manhattan cultural scene gave their work a kind of artistic credibility. Yet their avant garde impulses were always counterbalanced by a veneration of the soul, funk, and blues music that shaped rock and roll’s art and history. In what follows, I trace the long and winding road Talking Heads took in their journey to True Stories, both as film and as album.

Making the scene

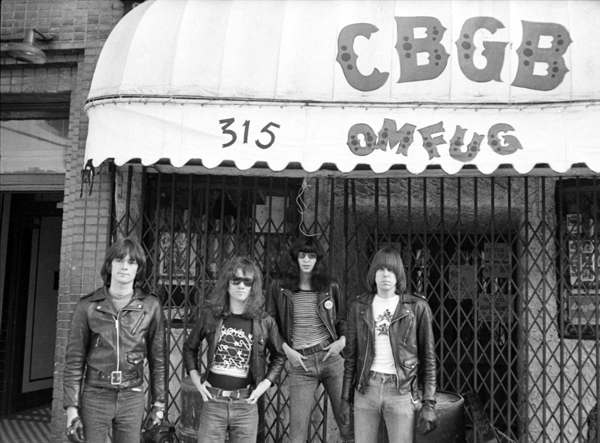

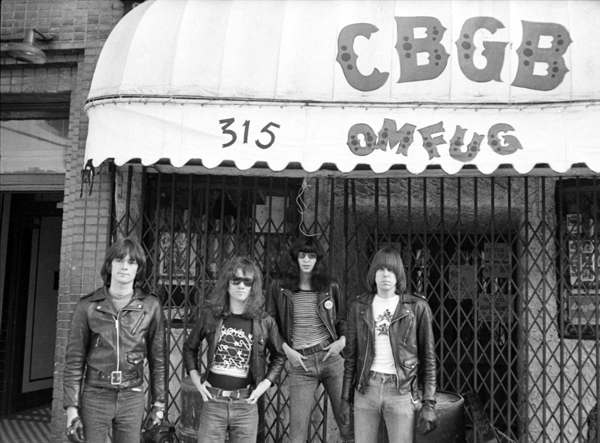

The Ramones at CBGB in the 1970s.

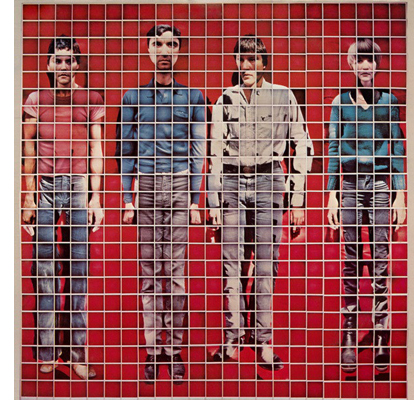

David Byrne’s band, Talking Heads, is almost certainly the most successful group to emerge from the downtown New York music scene of the late 1970s. Of the eight albums the band released between 1977 and 1988, seven of them were certified either gold or platinum. Little Creatures, the album released just before True Stories, went double platinum, selling more than two million units. So did Stop Making Sense, the soundtrack to their concert film directed by Jonathan Demme.

At the start of their recording career, much of the energy surrounding the New York music scene centered on the venerable East Village club, CBGB. Its name was short for “Country, Bluegrass, and Blues.” Yet the bands who came to be identified with the venue were about as far away from roots music as you could get. Initially, CBGB was associated with the emerging American punk rock scene. The Ramones were frequent performers as were the Plasmatics, Richard Hell and Voidoids, and Johnny Thunders’ band, the Heartbreakers.

Yet the range of musical styles represented at CBGB ventured quite far afield from the sped-up, chainsaw guitar sounds of punk. Patti Smith channeled her inner Rimbaud over Lenny Kaye’s Nuggets-inspired guitar lines. Television featured the evocative string-bending of Tom Verlaine. who stretched out in long solos using modal scales that fused Ravi Shankar with John Coltrane. James Chance and the Contortions showcased the wild saxophone playing of their frontman, specializing in a peculiar form of avant-funk jazz. Blondie began by refashioning sixties garage rock into their own brand of punk. But their style became more eclectic, branching out to include disco, calypso, and rap. They attained a huge crossover success in the process, thanks to lead singer Debbie Harry’s sex appeal and sultry alto.

Talking Heads sounded like none of these. “New Feeling,” the second track on their debut album, established the template for the band’s music: skittering guitar lines, tightly wound rhythms, and David Byrne’s strangled yelp. Its spare, spiky pop sound featured the rhythmic interplay of Byrne’s and Jerry Harrison’s guitar lines and the precise sixteenth note fills of drummer Chris Frantz.

Talking Heads 77 occasionally added elements that slightly broadened their musical palette. Think of the steel drum sounds that color “Uh-Oh, Love Comes to Town” or the loping electric piano chords of “Don’t Worry About the Government.” Indeed, the latter wouldn’t sound out of place in a Sesame Street bumper.

Yet, the album’s flagship single was “Psycho Killer” for a reason. Its nervy energy epitomized the group’s sound in its early days at CBGB. This was rock and roll to be sure. But it seemed like the kind of thing the subject of Edward Munch’s The Scream would dance to if he ever got off that bridge.

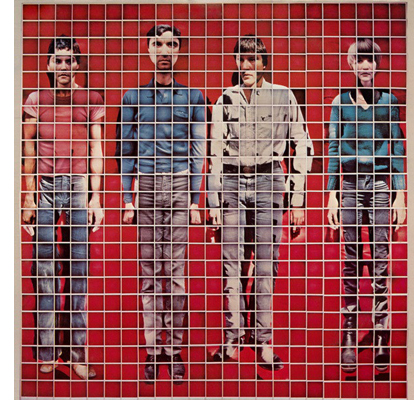

Talking Heads’ follow-up, More Songs About Buildings and Food, initiated a period of fruitful collaboration with producer Brian Eno. Using synthesizers and other keyboard instruments to flesh out the band’s sound, Eno nudged the Heads toward more danceable tunes. Built on Tina Weymouth’s pliant, bouncy bass lines, songs like “Found a Job” and “Stay Hungry” saw the band incorporating elements of seventies funk, soul, and disco. The band’s cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” also gave the group their first chart hit.

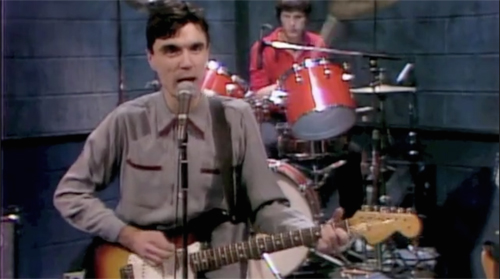

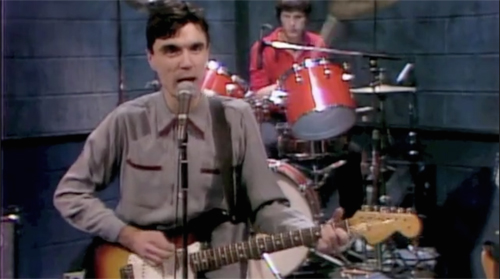

That single’s slow climb peaked the same week of Talking Heads’ television debut on Saturday Night Live. For many viewers, this was their first encounter with Byrne’s “Norman Bates meets Pete Townshend” persona. And, even though Byrne’s hipster nerd desperation seemed the absolute antithesis of Green’s “lover man” come-on, his apparent interest in exploring black musical idioms felt almost painfully sincere.

Bringing Noho to the bush of ghosts

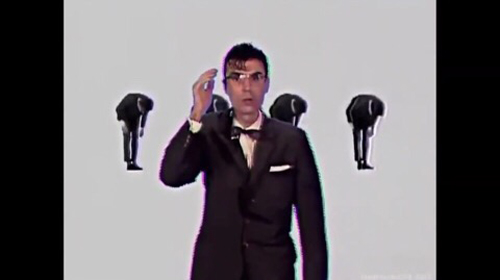

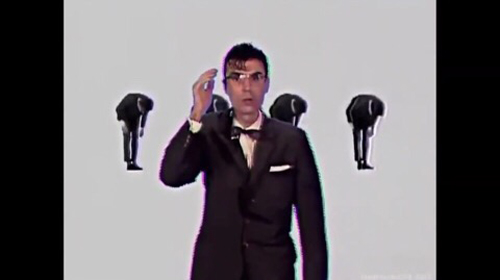

Music video for Once in a Lifetime.

Over the next three albums, the Heads’ collaboration with Brian Eno pushed them even deeper into world musical cultures. The band simplified their song structures, but increased the complexity of their arrangements and instrumentation. “I Zimbra” added Cuban, Brazilian, and African percussion along with the signature stylings of Robert Fripp’s guitar work. Remain in Light‘s densely layered synthesizers, various types of drums, and percussion atop the guitars, bass, and trap set that had been the core of the group’s sound since their first album. Created through countless overdubs that enabled each band member to play percussion alongside their normal instruments, the album featured extended Afrofunk and worldbeat grooves that interwove “call and response” vocal lines with intricate polyrhythms.

To recreate this sound on stage, the band recruited several players from other groups. On tour Talking Heads became a sort of New Wave supergroup with King Crimson’s Adrian Belew on guitar, Ashford and Simpson’s Steve Scales on percussion, and Funkadelic’s Bernie Worrell on keyboards. The expansion of Byrne’s musical vision was nothing short of stunning. Using improvised jams and communal music-making as a point of departure, Remain in Light went well beyond the faux gospel and art school irony of “Take Me to the River.” By mixing preachers’ rants with the wordplay of Bronx rappers, Byrne discovered his inner Fela Kuti.

Talking Heads start making cents (on sync licenses)

1983 would prove to be a watershed year for Talking Heads. The band released Speaking in Tongues, which spawned their first top ten hit, “Burning Down the House.” The record also represented a kind of apotheosis. It was less musically adventurous than Remain in Light. But it seamlessly blended the band’s early New Wave sound with its later Afrofunk influences. Instead of grooving on one chord, most songs on Speaking in Tongues contained more conventional harmonic changes. And instead of building songs out of shorter “loops,” the new record featured much more traditional song structures with clear demarcations of verses, choruses, and bridges.

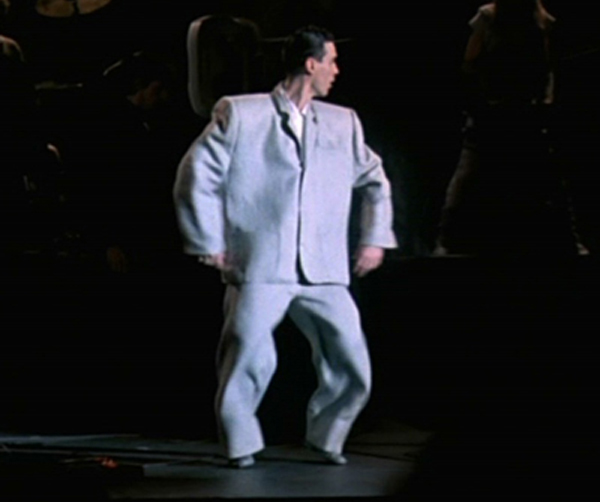

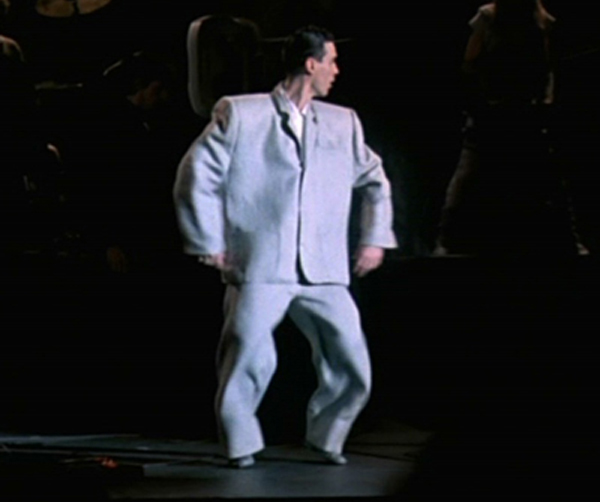

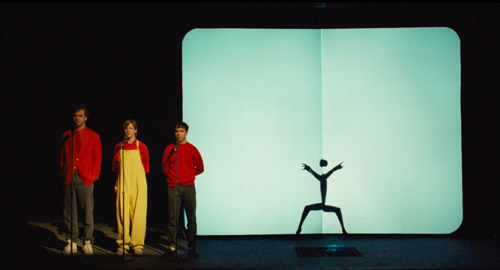

The album also served as the centerpiece of Jonathan Demme’s concert film, Stop Making Sense, which was filmed over four separate dates in December of 1983 at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles. The set list more or less traced the history of Talking Heads, beginning with David Byrne performing “Psycho Killer” on an acoustic guitar accompanied by a rhythm track played back by a boombox. It closed with a performance of “Crosseyed and Painless” that featured the full tour ensemble, including Scales, Worrell, guitarist Alex Weir, and two female backup singers. In between, Byrne bounced around the stage in his big white suit, turning the concert stage into a space for performance art. As before, Byrne seemed to self-consciously reject the usual rock star poses. Instead, he shook, squirmed, and jerked like a giant white Gumby on a hot tin roof. Stop Making Sense went on to become a modest commercial success and won the National Society Film Critics award for Best Documentary of 1984.

Between 1983 and 1986, Talking Heads also saw their profile raised by the use of songs in other popular films. The group had already been featured in a motley group of titles prior to Speaking in Tongues. “Life During Wartime” was included in Alan Moyle’s Times Square (1980), a teen comedy about two aspiring punk singers in New York. But so was almost every other hot artist of the moment, such as Joe Jackson, Gary Numan, the Cars, the Cure, and the Pretenders. The Heads had also performed “Psycho Killer” in Bette Gordon’s short film, Empty Suitcases.

The industry surge in soundtrack sales in the early to mid-eighties, though, gave Talking Heads access to more high-profile studio projects. “Burning Down the House” made an appearance in the rowdy fratboy comedy, Revenge of the Nerds. And the use of “Once in a Lifetime” over the opening credits of Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) fueled the song’s return to Billboard’s Hot 100 more than five years after it was released.

A much more interesting case of music licensing occurred with the push given to “Swamp,” the opening track on side two of Speaking in Tongues. Robbie Robertson of The Band selected the song for inclusion on the soundtrack of King of Comedy (1982) well before the album was released. It then appeared again just months later in the Tom Cruise teen comedy, Risky Business. The reuse of “Swamp” so soon after Scorsese’s film might well be a case of serendipity. Paul Brickman, Risky Business’ screenwriter and director, likely glommed onto it when he heard David Byrne intone the phrase “risky business” in the song’s last verse.

“Swamp,” though, anticipated yet another change of direction in the band’s music. Unlike the worldbeat influences that were still evident in the rest of Speaking in Tongues, the track returned Talking Heads to American terra firma, more specifically the musical idioms of the Mississippi delta. A slow, blues shuffle tune with strong triplet rhythms, “Swamp” was truly unlike anything else the group had done before. Floating on Bernie Worrell’s funky synth textures, it sounded like a Parliament cover of an old Muddy Waters song. The fact that Byrne’s vocals deliberately mimicked John Lee Hooker just added to its overall strangeness.

But just as “I Zimbra” presaged Talking Heads’ foray into Afrofunk, “Swamp” foreshadowed the band’s turn toward American roots music. Their follow-up album, Little Creatures, showed the band branching out even further with the rollicking zydeco of “Road to Nowhere” and the soporific country weeper, “Creatures of Love.” All of this would eventually lead Byrne and co. to True Stories and to a state with a musical canvas almost as large as its geography: Texas.

More songs about voodoo and dreams

In the special features on Criterion’s excellent edition of True Stories, David Byrne acknowledges that his conception of the film was partly inspired by his admiration for Robert Altman’s Nashville. The resemblances between the two films aren’t hard to discern. Both films feature multiple protagonists and use setting to unify the film’s different plotlines. Both films include the perspectives of one or more outsiders — The Narrator in True Stories, Opal and John Triplette in Nashville — who serve as the viewer’s guide to the community each explores. Both films also involve preparations for a local celebration – the talent show, the political rally – to motivate musical numbers by a variety of performers, much in the manner of a revue or jukebox musical.

Texas is home to a distinctive mix of different kinds of “roots” music. Byrne was keen to capture that breadth. In an essay on the music written for True Stories, Byrne says, “I realized there was a lot to represent – rock, country, Tex-Mex, polkas, Latin, lounge jazz, disco, and some made-up genres, like an accordion marching band.” Trips to scout locations for the film brought Byrne into contact with a number of clubs and musicians. He then offered some local musicians an opportunity to contribute to the score. None of the groups represented is particularly well known outside of True Stories. Indeed, neither the Panhandle Mystery Band nor Brave Combo achieved even the modest fame accorded to Texas singers like Delbert McClinton or Freddy Fender. Still these local musicians definitely added to the “specialness” that Virgil represents.

In his collaborations with local musicians and the songs written for various actors to sing in True Stories, Byrne found himself serving two masters. On the one hand, Byrne wanted to pursue his vision for the film and to write songs that express the feelings and perspectives of various characters. On the other hand, though, Byrne also had to make sure these numbers still worked as Talking Heads tracks. It seems likely that Warner’s willingness to support the film depended upon the ancillary revenues they hoped to earn from the soundtrack. The Heads had been signed by Sire Records, a subsidiary of Warner Music. Given the band’s previous sales, a new Talking Heads album served as a hedge against the film’s disappointing box office.

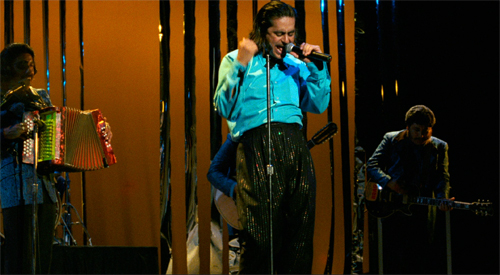

Virgil wants its MTV

The three songs Talking Heads recorded specifically for the film – “Wild, Wild Life,” “Love for Sale,” and “City of Dreams” — are perhaps the best illustration of Byrne’s need to create corporate “synergy” in the relationship between True Stories and its music ancillaries. All of them are foursquare rock and roll songs. No doubt they reassured Warner Bros. that they had commercially marketable singles that could generate radio airplay and hopefully drive traffic to movie theaters. “Wild, Wild Life” would become the second biggest hit in the band’s history, peaking at #25 and spending about five months on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

Notably, though, Byrne insisted these weren’t genuine Talking Heads records. Instead, they represented the band’s attempts to sound like other popular artists. Byrne described the role models for these tracks:

The closing song, “City of Dreams,” is my version of a Neil Young anthem. Its lyrics echo the history lesson at the beginning of the film. “Love for Sale” was our version of a Stooges song, and “Wild, Wild Life” was my attempt at writing a song like something one might hear on MTV at the time.

Byrne doesn’t give us a lot to go on here, but we can discern at least some similarities between the songs and the artists he cites. On “City of Dreams,” Byrne’s voice doesn’t have the fragility that Young’s “high lonesome” tenor conveys. But the lyrics evoke the kind of imagery found in some of Young’s most famous songs, especially those that relate the experience of Native Americans. Indeed, Byrne’s verse about the Spanish search for gold wouldn’t seem out of place in “Cortez the Killer,” the standout track on Young’s 1975 album Zuma.

With its crunchy guitar riff and drum break, “Love for Sale” at least nominally sounds like it could be a track from the Stooges’ Fun House. It certainly channels some of the proto-punk energy that made the Stooges, especially lead singer Iggy Pop, a revered cult band in the early seventies. Yet Talking Heads’ performance shows their customary clockwork precision, and the record generally lacks the kind of wild abandon that one associates with the Stooges’ best tracks. Eric Thorngren’s audio engineering of “Love for Sale” also adds a layer of studio polish that an album like Raw Power most pointedly refuses. In an odd way, the recording gives us some insight into how the Heads might have sounded had they been a punk band in their CBGB days.

Perhaps the bigger irony here is that the song functions as an interpolated music video watched by the Lazy Woman during a bout of channel surfing. It shows Byrne’s usual eye for inventiveness within the form: silhouettes, primary colors, and a surrealist arc in which each band member is molded into a chocolate figurine wrapped in foil. Yet here is where the similarity between the Heads and Stooges ends. Iggy Pop may have been known for pouring oil or honey on his body during Stooges concerts. But in 1986, the Stooges were about the last band one would expect to see on MTV.

“Wild, Wild Life” is motivated in a similar way. Heard in a Virgil dance club, much of the film’s cast lip syncs to it against a bank of video monitors. Like “Love for Sale,” this footage became the basis of a very successful music video promoting the film. In a bit of an in-joke, guitarist Jerry Harrison twice appears onscreen dressed as an iconic rival artist: first as Billy Idol, then as Prince. (Note that Tina Weymouth also appears with Harrison as a fetching Apollonia.) Still, the lack of specificity in Byrne’s description suggests that it was Talking Heads’ attempt to make a rather generic pop record. In contrast to the film’s celebration of “specialness,” Byrne’s explanation of the song’s purpose functions as a backhanded critique of MTV’s role as tastemaker. In trying to sound like everyone, “Wild, Wild Life” fit quite snugly into the music network’s video rotation.

The sage in bloom is like perfume

The film’s remaining songs are performed by characters. They illustrate Byrne’s desire to capture the breadth of Texas’ musical culture in a variety of idioms. Other bits of music are also interspersed between these numbers. There are snatches of nondiegetic score based on Byrne’s two “dream” songs (“City of Dreams” and “Dream Operator”). Meredith Monk contributed a brief minimalist theme that is featured in the film’s opening and closing scenes. It is perhaps the clearest reminder of Byrne’s outsider status, enveloping the film within the sounds of the downtown Manhattan arts scene. It also includes Carl Finch’s “Buster’s Theme” as music played during True Stories’ infamous accordion parade.

At least two songs evoke the swamp pop of Eastern Texas, which shares much of its sound with the music of New Orleans. “Hey Now” features the simple tonic/dominant changes and “call and response” strophic patterns heard in second line parades during Mardi Gras. Sung by children, it sounds like a modernized version of the Dixie Cups classic, “Iko Iko.”

“Papa Legba,” on the other hand, carries a more pronounced “island vibe,” conjuring the Cuban and Jamaican styles that were such an important influence on Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, and Lloyd Price. Performed by the great Pops Staples, the style is apt since the song is ostensibly an appeal to a central figure in Haitian folklore. (Legba is a demigod in voodoo culture who facilitates communication between living beings and the souls of the dead.) Staples expressed concern about this scene. The actions of his character, Mr. Tucker, ran squarely against the actor’s Christian faith. Yet, despite Staples’ literal embodiment of the “magic negro” trope, Tucker’s actions here come across as rather benign. He acts on Louis’ behalf, and both characters seem so decent and honest that their resort to sorcery seems quite harmless.

In other films and television shows, such as Crossroads or American Horror Story, Legba is often trotted out as a stand-in for Satan himself. In True Stories, though, Tucker’s Legba number is a slightly less hokey version of Leiber and Stoller’s “Love Potion # 9.”

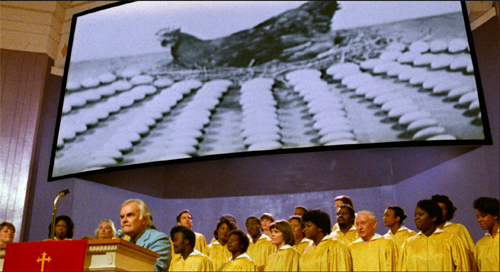

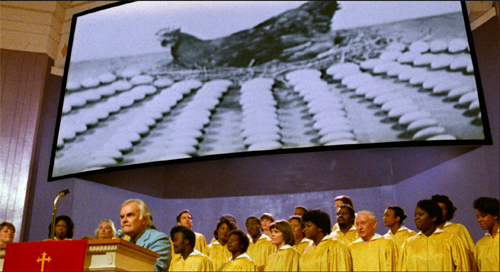

“Puzzling Evidence” is a straightforward gospel number, delivered from the pulpit by John Ingle as The Preacher. As an enumeration of possible conspiracies, the scene might seem today as QAnon avant la lettre. But sober reflection suggests the song is further evidence that Richard Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” of American politics has a long and rich history.

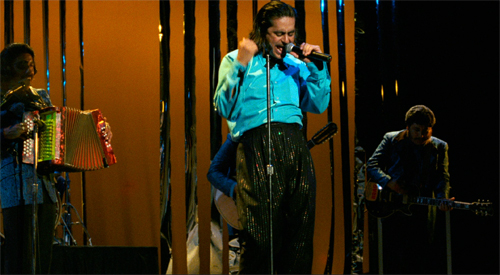

“Radio Head” represents the rich tradition of Hispanic styles in Texas musical culture: Tejano, conjunto, orquesta, mariachi, corrido. As performed by Tito Larriva, the tune borrows heavily from conjunto, which originated in the 1870s and fuses Spanish and Mexican vocal styles with the polkas, waltzes, and Mazurkas played by German and Czech immigrants. A central element of conjunto is the combination of 12-string guitars with button accordions. The latter has a distinctive reedy, yet sweet timbre contrasting that of the piano accordion.

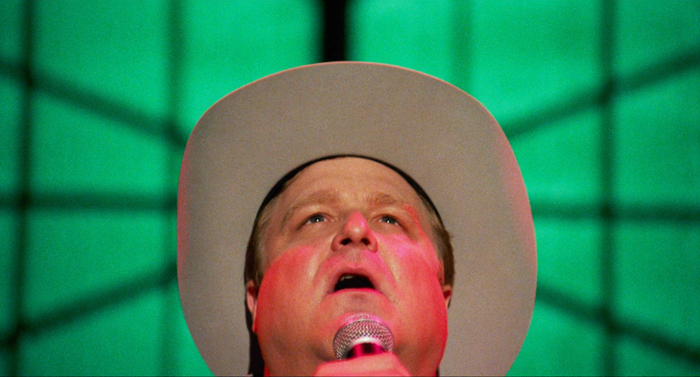

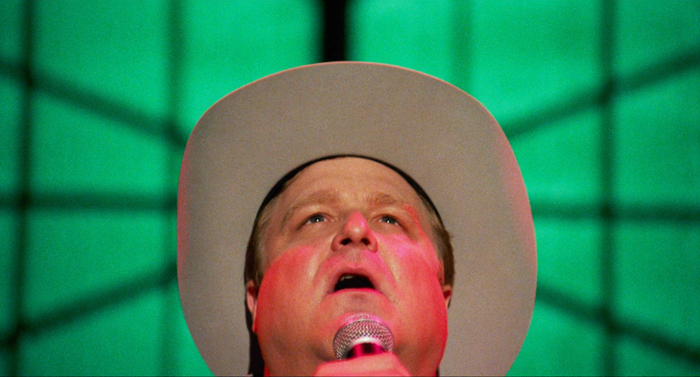

“Dream Operator” and “People Like Us” round out Byrne’s portfolio by borrowing different from different strands of country music. The former is a shimmering waltz reminiscent of the Texas Troubador, Ernest Tubb, and the Western swing style of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. “People Like Us,” which is performed by Louis at the talent show, is an up-tempo slice of neo-honky tonk that features the requisite fiddle and steel guitars. The lyrics also voice the kinds of populist sentiment that became di rigeur in the genre by the 1980s.

At its best, in the music of Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, George Jones, and Loretta Lynn, country music spoke eloquently of the simple pleasures of nature and family. It also explored the problems of ordinary folks, such as infidelity, divorce, and alcohol abuse. At its worst, though, such populism lapses into knee-jerk jingoism.

Byrne’s lyrics gesture toward the former of these two strains. It attests to certain Texas values: stubborn pride, an independent streak, and a resilience in hard times. Louis’ seeming humility and sincerity proves to be catnip for the Lazy Woman. She proffers the marriage proposal that Louis has sought throughout the film. In providing the resolution to the central plotline, “People Like Us” brings the narrative and Byrne’s musical journey through Texas to a fitting conclusion.

Changes in latitude, changes in attitude

For me, perhaps the most striking thing about “People Like Us” is its distance from Talking Heads’ early work. Compare it, for example, with “The Big Country,” the closing track on More Songs About Buildings and Food (below). Here Byrne’s narrator assumes a God-like view of the U.S. and its “people down there.” Imagined from maps and viewed from airplanes, the lyrics survey a cornucopia of Americana in the references to ball diamonds, whitecaps, farmlands, highways, and buildings. Yet, each chorus undercuts this encomium to the “big country” by concluding “I couldn’t live there if you paid me.”

In conversation David (Bordwell rather than Byrne) often praises “the spontaneous genius of the American people.” Is Byrne doing the same in True Stories with its portrait of small-town life as a mixture of performance art and irresistible kitsch? Or does he still occupy the previous Godlike position described in Louis’ song, laughing disdainfully at “people like us?”

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life. At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.

Yet somehow invoking the old distinction between “author” and “narrator” obscures something important about the way True Stories fits into Talking Heads’ history as a band. The songs Byrne wrote for the film seem like a culmination of the group’s turn toward American roots music in the mid-1980s. Moreover, as Byrne has shown as an impresario for his own Luaka Bop label, he has genuine admiration for an enormous variety of vernacular pop idioms. In its own way, Talking Heads’ absorption of regional American musics on Little Creatures and True Stories might be viewed as signs of artistic growth rather than the stylistic poaching of smartasses from Manhattan.

Still there is a third possibility. As my colleague Jonah Horwitz pointed out to David and me, True Stories also seems to bear a strong relation to the Lovely Music movement epitomized by Robert Ashley, “Blue” Gene Tyranny, and Peter Gordon. In Jonah’s words, this axis of modern composition is “characterized by a suspension of judgement, gaping appreciatively at the banality/beauty of America and Americans, bridging the gap between structural/minimalist ‘new music’ and popular forms like rock and country music and soap opera.”

But is this appreciative gaping is really just postmodernist snark? Adrian Martin suggests as much in his original review of the film. And faux sincerity, in and of itself, might be viewed as the deepest, most pernicious form of cynicism. Taking particular issue with the chorus of “People Like Us,” Martin writes, “According to this reading, which the film abundantly invites, its viewpoint is immaculately distant and sneering.” Citing its “patronizing, condescending tone,” Martin ultimately bemoans the fact that True Stories draws attention away from more “authentically funky little American films” that won’t get seen.

Is this ultimately where Byrne lands? Perhaps. The lyrics certainly can be viewed as a faux naif expression of Redneck stupidity.

We don’t want freedom

We don’t want justice

We just want someone to love

But if we dismiss “People Like Us” as evidence of authorial condescension, one misses the key insight that the song has to offer. Much hedonics research suggests that there is a more complex way of understanding such sentiment.

Freedom and justice may be necessary conditions of human happiness, but they are hardly sufficient. Abstract ideals ultimately don’t mean much absent the human connections that define our workaday world. Such craving for social interaction and a feeling of belonging is one reason why respondents in hedonics studies claim they would forgo a $10,000 raise for the opportunity to become a member of a small, but active club. Moreover, neuroscience also shows that romantic love produces a sense of electrochemical wonder within the brain. Not all of these changes are positive ones, but the flood of dopamine that accompanies sexual attraction helps explain why love can be both pleasurable and addictive.

Viewed from this perspective, Louis’ sentiments in “People Like Us” are far from guileless. By emphasizing toughness and resilience, the song asserts that homeostasis is possible even in the most hardscrabble life. And life is made rewarding and meaningful by the social bonds that unite us in a common humanity. Perhaps folks out there will see me espousing a version of the feigned sincerity for which True Stories is equally guilty. But given the way Byrne’s film judders my own pleasure center…. Well, let’s just say I’ll proudly wear my heart on my sleeve.

Thanks to David Byrne, Ed Lachman, Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Lee Kline, Ryan Hullings, and the rest of the Criterion team for this edition. The quotation from David Byrne comes from the booklet accompanying the disc.

Thanks also to Jonah Horwitz for helpful comments on the music, and Adrian Martin for signaling his critique of True Stories.

Other work by Jeff relevant to this analysis includes The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music (Columbia University Press, 1998) and his survey of the field ”The Tunes They are a-Changing’: Moments of Historical Rupture and Reconfiguration in the Production and Commerce of Music in Film,” in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies, ed. David Neumeyer (Oxford University Press, 2013).

True Stories.

Posted in Directors: Byrne, Film and other media, Film music, Film technique: Music, Film technique: Performance |  open printable version

| Comments Off on From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES open printable version

| Comments Off on From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES

Sunday | December 16, 2018

True Stories (1986).

DB here:

Fall of 1986 saw two helpings of twisty Americana from a pair of Davids. Lynch’s Blue Velvet was released in September, and Byrne’s True Stories followed less than a month later. In a year dominated by the Goliath known as Top Gun, the Davids stood little chance. As of January 1987, Blue Velvet had made $3.5 million domestically, while True Stories, on a budget of $5 million, earned only $1.2 million, less than The Toxic Avenger. But both acquired cult followings, especially on videotape. Fall of 1986 saw two helpings of twisty Americana from a pair of Davids. Lynch’s Blue Velvet was released in September, and Byrne’s True Stories followed less than a month later. In a year dominated by the Goliath known as Top Gun, the Davids stood little chance. As of January 1987, Blue Velvet had made $3.5 million domestically, while True Stories, on a budget of $5 million, earned only $1.2 million, less than The Toxic Avenger. But both acquired cult followings, especially on videotape.

In the decades since, Blue Velvet has received luxurious DVD and Blu-ray treatment. True Stories, however, wasn’t well-served by Warners’ offhand DVD transfer. Now the Criterion people have given us a lustrous Blu-ray edition of another movie that shows that the 1980s weren’t all big hair, padded shoulders, and John Hughes pity parties. This will quickly become a fetish object for the vast True Stories cult. Visit us way down in the codicil for details.

This movie has been a favorite of mine since I saw it in 1986. Kristin gave me a 16mm print for a long-ago birthday. I’ve wanted to write about it for years, and the Criterion release provides a nifty opportunity. (Full disclosure: I’ve done work for the company. Fuller disclosure: I happily paid for this Blu-ray.)

But I realize that music is so ingredient to the sneaky pleasure of this film that I need expert help. Hence this entry will be followed by one by Jeff Smith. Jeff, as you probably know, is our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our FilmStruck/Criterion series Observations on Film Art, as well as being a frequent contributor to the blog. His deep knowledge of music will yield an entry you’re sure to find interesting.

Many true stories

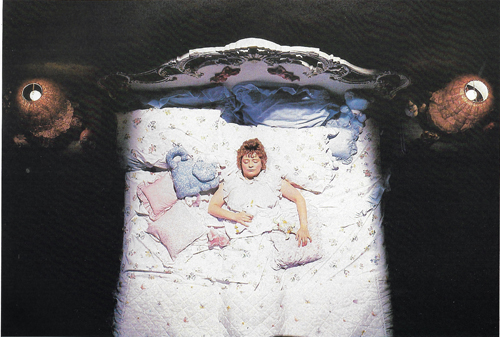

In the film’s publicity Byrne was at pains to claim that he drew the narrative material from tabloid articles he collected over years of touring with Talking Heads. These clippings supply the initial characterization of the lovelorn Louis Fyne, the Lazy Woman lolling in bed, and the Culvers who never speak directly to each other. Other aspects of the film come from fringe culture more generally, like conspiracy theories and extraterrestrial communication. (The Computer Guy sends signals “up”; in a cut scene available on the Criterion release, he’s transmitting New Age music to be picked up by aliens.)

At the end of the published screenplay, Byrne admits that he used these and other faits divers as inspiration more than as well-documented material. Is this stuff true? “I don’t even really care. . . . It seems to give the movie an extra little bit of excitement to think that maybe it could be true.” The dossier he collected includes not just weird anecdotes but articles about prefab architecture, the computer industry, the malling of America, and other social developments. These are just as important “true stories” as any tales from The Weekly World News.

Do all these stories add up to A Story? Sounding a bit like Wim Wenders, Byrne notes: “Movies are a combination of sounds and pictures, and stories are a trick to get you to keep paying attention.” So he began with drawings, which he posted on walls and kept shuffling around. Eventually two screenwriters, Beth Henley and Steven Tobolowsky, pulled a plot out of them, but Byrne went on to fragment that considerably. The result shifts between episodic and classically plotted cinema.

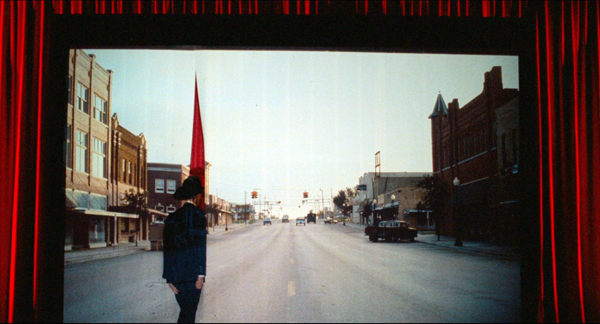

True Stories has a clear time frame: four days, from Wednesday to Saturday night in and around the fictitious town of Virgil, Texas. This period is followed by an indeterminate gap, ending in an epilogue showing a wedding and the Narrator’s departure. The whole tale is framed, beginning and end, by the solfège song of a little girl on the road. Jonathan Demme told Byrne that a movie needs a clock, so the plot creates a soft deadline, the variety show on Saturday.

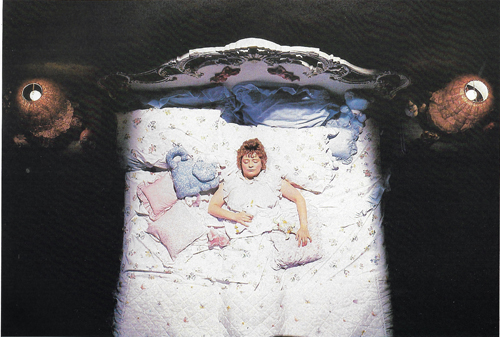

We get something like a tandem story line. First, there’s Louis Fyne’s quest for a woman to marry. More casually, we explore everyday life among the locals. Mostly these revelations come through the wanderings of the Narrator, a lanky outsider dressed in cowboy clothes nobody else wears and possessed of hesitant curiosity. At times, without his guidance, we get other glimpses of town life, such as the habits of the Lazy Woman and the divination powers of her servant Roberto. There are also some very brief vignettes on the margin. The big show ties up the romance line of action when Louis’s stirring performance of his song, “People Like Us,” rouses the Lazy Woman to propose to him. Despite Byrne’s desire to avoid “too much story,” I think most viewers are grateful for a fairly tidy plot that helps us engage with these offbeat characters.

Our Town (not)

Because of the film tries to survey small-town life, it’s been compared to Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, and it seems that Byrne considered that one model. Still, the differences are pretty important.

Our Town concentrates on two families in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire. People live close together and duck into each other’s kitchens and stop to gossip in front yards. But in Virgil there’s mostly no there there. That town is seen chiefly in empty night vistas, lit by blinking traffic lights. Only the parade seems to energize the fairly sparse main drag.

Virgil is hollowed out; all the big stores relocated to the mall. This is the new Main Street, the Narrator explains, and even the music club sits among boutiques and chain stores. Elsewhere, people’s homes homes squat in splendid isolation, like the Lazy Woman’s mansion, or in half-finished developments pasted against a desolate horizon. People have to reinvent themselves in new spaces, we’re told; the cloistered community of New England hasn’t been rebuilt in the exurbs of the New Southwest.

Hence the importance of driving scenes, of which the film has some of the most beautiful in all of cinema. The Narrator cruises the flat, baked landscape, the sky reflected gorgeously in the sheen of his red convertible. Without a car, you can’t join the community, and the Sesquicentennial Parade boasts its share of customized transport, from the Low Riders to the Red Mustang Shriners.

Our Town builds its action out of work and family routines, ceremonies marking marriage and death. The pathetic fate of Simon Stimson, the church musician, warns of the perils of solitude. The romance of George and Emily shows that marriage at least provides companionship and at most nourishes devotion. Across three days separated by years (and with a flashback to a fourth day), Wilder tries to put this entire mundane rhythm into a cosmic context, a cycle of birth and death that should teach us to appreciate each precious instant of life.

So too, in its way, does True Stories. But here the work routines are post-Fordist: Earl Culver explains that people don’t differentiate between working and not working. He’s thinking of techies like the Computer Guy, who ransacks the mall for equipment to tinker with at home. But the blue-collar employees get into the 24/7 spirit. They make their day on the assembly line as casual as lunchtime, talking about love and money and quirks, even crooning to one another. Louis in the Clean Room can spare a moment for a monologue about his love life. At the bar and the mall, the same workers cross paths. In Greater Virgil, leisure is an extension of the break room.

The only family we see in detail are the Culvers, who under a surface perkiness play out rigid roles (and the parents don’t talk to one another). The Cute Woman and the Lying Woman seem to want more, as both meet Louis on dates, but neither can really break out of her obsession (smiling, lying). Even Louis’s eventual mate, the Lazy Woman, gets out of bed only to phone him. After the wedding he has joined her under the covers, presumably to watch TV forever.

Death haunts Our Town, and the same goes for True Stories in its original form. In the screenplay and footage shot, the Cute Woman dies during the parade (overcome by the sweetness emanating from the babies on display). The film’s final scene would have shown her funeral, where the Narrator shares thoughts with Roberto. Byrne deleted her death and burial as too sad, thereby also losing her melancholy Molly-Bloomish bed monologue. (These scenes are in the supplemental material as analog video; below are production stills.)

In a way, the burial would have rounded things off. While Louis’s quest for a wife is rewarded, the Narrator’s inquiry into Virgil’s not-so-wild life could have ended with his discovery of a death from pathetic obsession. It would have been marked by the Lying Woman’s pointless lie: “She was my best friend. . . . We had so much in common.” The comic grotesque would have become the pathetic grotesque.

Excising this scene leaves a gap. After Louis’s wedding (which the Narrator doesn’t attend), the Narrator is seen simply driving off and reflecting on why he likes to forget. Denying us a farewell between the two characters who have built up a friendship in the course of the film, expelling the foreign visitor back to the road and the horizon, Byrne gives us another flavor of sadness. Their encounter was as transitory as everything else in this post-Our Town landscape. And as we’ll see, the Narrator’s meditation as he drives off carries a burden as important as the postcard addressed to “The Mind of God” in Our Town.

Virgil’s guide

Our Town’s Stage Manager is omniscient. He knows everything about Grover’s Corners, past, present, and future. (He predicts the death dates of some people as he introduces them to us.) He indeed stage-manages the action, calling on experts and even summoning George and Emily to reenact their courtship. Yet although he can interact with characters, he can stand outside the story and address us directly. His presence comes to seem comfortable and reliable. He’s an all-controlling guide—at least until the climax, when Emily takes over the narration and tries to return to the world of the living.

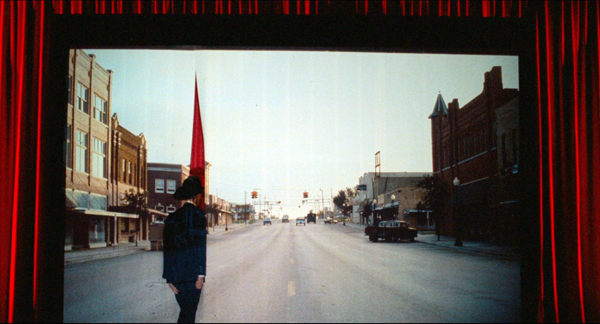

The Narrator of True Stories doesn’t stage-manage anything. He starts out omniscient, lecturing to us about the history of Texas and the occasion for Virgil’s celebration. But once he steps through the slit in the screen, he mostly becomes a naïve, passive presence. He quizzes locals as they deliver monologues, and he seems politely puzzled by their outrageous claims. His dude-ranch getup and geeky silhouette make him almost childlike. He marvels at all the nicknames for highway drivers and is staggered when he sees a four-car garage. (“Who can say it isn’t beautiful?”) The film is almost over when he assures us that this is not a rental car: “This is privately owned.” Who ever thought to ask? And now that you mention it, who does own it?

True, the Narrator issues grown-up pronouncements about the Varicorp chip-assembly plant, but it’s in the bland tones of a PR brochure. He gives us stray factoids like a schoolboy proud of memorization. Even his pronunciation (“special-ness”) suggests either ignorance or awkward efforts to be cute. He might be the incarnation of the voice in one of Byrne’s Knee Plays (“Social Studies”):

I thought that if I ate the food of the area I was visiting

That I might assimilate the point of view of the people there

As if the point of view was somehow in the food….

When shopping at the supermarket

I felt a great desire to walk off with someone else’s groceries

So I could study them at length

And study their effects on me

What sort of narrative authority is this?

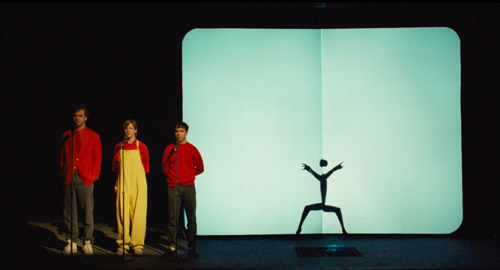

A sort, I think, we find in the calculated vacancy of post-Pop art culture. It’s the blankness of (Texan) Robert Wilson’s po-faced theatre spectacles, where counting off numbers and metronomic gesturing suggest behavior “on the spectrum.” It’s Jeff Koons, maker of gilded Michael Jacksons, saying, “Removing judgments lets you feel, of course, freer, and you have acceptance of things, and everything’s in play, and it lets you go further.” It’s above all Warhol, who perfected affirmative blankness in art and life.

I’m not more intelligent than I appear. . . . The world fascinates me. It’s so nice, whatever it is. I approve of what everybody does.

It’s an artistic strategy that invokes what Viktor Shklovsky called “defamiliarization” and Brecht called “estrangement.” The aim is to make us perceive ordinary life afresh, without the preconceptions we normally bring to it.

For Wilson, repetition and abstraction in the glowing stage box resensitize us to the unique signatures a body traces in space. For Warhol, and his decadent successor Koons, what gets “estranged” is contemporary mass culture, images of Elvis or soup cans or electric chairs or achingly cute balloon bunnies. We’re not far from Romanticism’s cult of the innocent eye, except that we’re not achieving a lyrical insight into nature but rather the thrill of seeing kitsch reveal elusive beauty and unexpected emotion. (I think that this is the point of Tati’s Play Time as well.)

Defamiliarization was of course on Thornton Wilder’s agenda too. Our Town’s bare-bones staging and breaking of the fourth wall aimed at refreshing our perception of stereotypes of rural life. The local-color writers before him had either celebrated small towns (Cather, My Ántonia) or condemned them (Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio), but neither had given them such archetypal poignancy. In Our Town, we might say that Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River gets redeemed by cosmic purpose.

Like others in the New York art scene, what Byrne sought to defamiliarize was American commodity culture. He had done it throughout the Talking Heads’s songbook, but with a sour, somewhat superior tone. That doesn’t entirely vanish here, I think, as in the moments of satire during Earl Culver’s dinnertime monologue, which becomes a pitch for letting a hundred Silicon Valleys bloom.

Such mockery is aimed mainly at corporate culture, while the community as a whole gets treated with a more grave affection. Does the sobriety check in the shadow of a Stop’n’Go (up top of today’s entry) owe something to Robert Wilson’s gestural tableaux? The gravity also stems from the planimetric framings, recalling not only Wilson but Walker Evans too.

These angles defamiliarize the landscape of exurbia, and their slightly comic monumentality will be echoed by Wes Anderson and other filmmakers of the 1990s.

As for the affection: I think the gee-whiz acceptance of commodity culture we find in Warhol and Koons becomes something different in True Stories. The good folk of Grover’s Corners, cradled among kin and friends, don’t need to assert their individuality, but the Virgilians define themselves by comparison shopping—and rebranding. True Stories is in part an appreciation of how people creatively remake all the crap pumped out for them to consume.

Amateur virtuosity

None of them seemed to feel alienated. They seemed to respond to mass culture in a very individual way—like, they take a prefabricated house and do something odd with it on the inside. I guess I was sort of proposing that here are these other possibilities—and maybe it was also a little bit of someone from New York imagining these little pockets of Utopia out there.

Near Spring Green, Wisconsin, sits the House on the Rock, a wondrous homage to the maxim “Too much is never enough.” In one hall a pneumatically controlled orchestra plays while you wander among a brewery, a pipe organ, and display cases, while above you hangs the engine of a whaling ship. With its carousels, dollhouses, Titanic souvenirs, and calliopes, welling out of the darkness in spotlights and glowing primary colors, the House on the Rock shows that if you plunge deeply enough into kitsch you come out the other side with something sublime, or at least surreal.

True Stories is in part about that plunge into tackiness, steered by a very 80s concern with the intersection of high and low. Can you endow kitsch with an avant-garde disorientation? Can you infuse avant-garde art with the good dirty fun of kitsch?

Byrne tries. The fashion show blurs the line between inspired tastelessness (a wedding dress like a wedding cake) and PoMo gallery art, the grass leisurewear provided by Bill Harding of Chicago. In the Criterion Making-of, Byrne insists that Adelle Lutz’s costumes are only one step beyond what you could find in Sears Roebuck of the day.

The Red Mustang Shriners, genuine as can be, constitute straightfaced populist eccentricity in a House-on-the-Rock vein. So do many of the variety acts, such as the Apache Belles and the eerie Shadow Dancers. And Mr. Tucker’s bungalow is actually the home of artist Willard Watson (aka The Texas Kid); footage of his encounter with Pops Staples is featured in the Criterion disc. This is another way the title levels with us: Many of the disconcerting images and sounds we encounter are as true as any story.

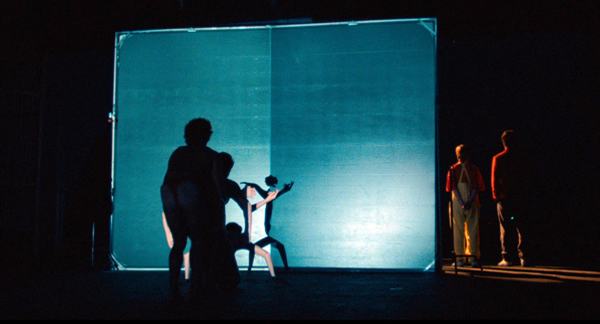

Some of the moments present authentic local music, like the accordion number in the Tex-Mex club where Ramon performs. Yet more often Byrne navigates the meeting of high and low in a striking way. While artworld-based Performance Art was going mainstream in the 1980s, Byrne starts from the other end and gives highbrow legitimacy to outsider performance art.

Virgil’s routines and ceremonies become occasions for impromptu performance. Instead of a traditional Happy Hour dance competition, there’s a lip-sync contest (“Wild, Wild Life”), with performers using their body to spin associations off the lyrics. A fashion show gets its own catwalk waltz, and a sermon on conspiracy theories becomes a stomping gospel tune. (It provocatively incorporates video clips assaulting the blue-sky tech promises of Earl Culver and Varicorp.) The Talking Heads music video “Love for Sale” absorbed TV commercials; now the film makes the video part of the flow of ads and programs on the Lazy Woman’s monitor. In Virgil, a parade can be a variety card, and a talent show can be as off-kilter as a string of pieces in a SoHo loft.

Amateurism isn’t necessarily clumsy; it has its own virtuosity. Why shouldn’t auctioneering be a sort of rap? Why shouldn’t children enact a love story with ventriloquist dummies? Why can’t people on the prairie come up with mysterious shadow choreography? At the climax, Louis is able to channel his search for love into a country and western song that he belts out with a confidence we haven’t seen from him before.

“Ideally,” Robert Wilson told an interviewer, “what we’d like to do onstage is to present ourselves.” The songs in True Stories, Byrne said, aimed to

give relatively placid people—like you or me—a justification for being vibrant and full of energy, for expressing themselves and exposing their insides to everyone else in the town.

Yet an audience isn’t necessary. Late at night a businessman dances alone at his office window, and a carpenter takes the empty stage to sing an aria. At the beginning and end, on the endless road, a little girl murmurs a song and makes mesmeric passes at nothing. She expresses herself in a fusion of naïve art and Downtown minimalism: It’s at once childish warbling and a Meredith Monk tune.

Our (favorite) town

That song stands out as a sort of primal beginning of all the film’s performances. It becomes the orchestral underpinning of the Narrator’s introduction to Texas history and his first trip down the expressway. The same spirit emerges in the 4H kids’ spontaneous brick ballet “Hey Now.” Childhood, it seems, is media-free, back to the basics of bodies and castoff noisemakers.

The kids’ direct expression is starkly different from the media-enabled activity we see among the grownups. One character, Ramon, is associated with radio; he thinks that each of us transmits our feelings on wavelengths he can pick up. Naturally, he’s written a song about it. The Lazy Woman, on the other hand, is identified with television, her main contact with the outside world.

Mr. Tucker is an LP aficionado; the Computer Guy works on early digital sound. Documentary film is represented as a collage of Puzzling Evidence. Print media surface as the hectic tabloids read by the teenagers.

The sensational stories in the tabs, the wellspring of Byrne’s film, shape the Lying Woman’s confabulations. Grover’s Corners was never plugged in to the flow of information like this.

All these factors—the mix of avant-garde and down-home artmaking, the nutty byways of populist performance art, people responding to a multimedia environment—heighten the effect of estrangement. The film’s opening montage has an arch knowingness, anachronistically mixing Raquel Welch cheesecake with dinosaur lore. Call it comic defamiliarization. But things grow more sincerely felt as we go along, so that the crazy grotesques of Virgil become not so crazy or grotesque after all. Many are waiting on love.

The Narrator, a tenderfoot in a Stetson, is curious and unflappable. His puzzled acceptance of everything that comes his way encourages us to forget what we think we know about hayseeds, the sovereign state of Texas, high-tech industry, suburban sprawl, prefab buildings, and dorky parades. The last we hear of him, he’s already deleting the file, but I doubt we can.

Well, I really enjoy forgetting. When I first come to a place I notice all the little details. I notice the way the sky looks, the color of white paper, the way people walk, doorknobs. Everything. Then I get used to the place and I don’t notice those things any more. So only by forgetting can I see the place again as it really is.

In the film’s final moments, the Narrator’s confession of Warholian passivity turns into a defense of defamiliarization that could have come from Shklovsky. “Art,” he wrote, “exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.” We can perceive true stories only by stripping away our preconceptions.

Byrne the creator has suggested that the film allowed him to find his way back to emotions beyond comfortable irony. “It was hard to go around not liking everything.” We can debate a long time why the end of Louis’s song, “We don’t want freedom/ We don’t want justice/ We just want someone to love,” both shocks and satisfies us. (Today, a Deplorable would change only the lyric’s last word.) But as an expression of sheer self-presentation, it’s hard not to sympathize with this Texas Bachelor.

Although the Narrator can forget, we don’t have to. According to the final song, we can remember this as our favorite town. With this film, Byrne makes sentiment safe for hipster consumption.

Working with Byrne and DP Ed Lachman, producer Kim Hendrickson and her team have supervised a brilliant 4K edition, the first time the film has been presented in 5.1 sound. They’ve included some precious material culled from new interviews, period footage, and excised scenes. There are also informative essays by Rebecca Bental, Joe Nick Patoski, Spalding Gray, and Byrne. The making-of is the best example of the genre I’ve ever seen, and the documentary on Tibor Kalman is quite informative on Byrne’s visual imagination. (The Criterion cover art is one of Kalman’s rejected designs.) One bonus short is a piece of analog video shot behind the scenes; another, by Bill and Turner Ross, is a contemporary return to the places shown in the film.

The film was shot full frame, to be masked in projection; some video versions displayed it at 1.37:1, others at 1.85:1, which is the one presented here. Kim was assisted by technical director Lee Kline, and audio supervisor Ryan Hullings. Also very helpful in the restoration and supplements was Christina Patoski, who organized a large portion of the original production. Many participants supplied photos and notes from preproduction.

Most of my quotations from David Byrne come from the Introduction in the book of the film: True Stories (New York: Penguin, 1986). Byrne’s remark about pockets of Utopia is quoted in Michiko Kakutani, “David Byrne Turns His Head to Movies,” New York Times (5 October 1986), 92.

The Warhol passage comes from Gretchen Berg, “Nothing to Lose: Interview with Andy Warhol,” Cahiers du cinéma in English no. 10 (1967), 40-42. The Robert Wilson quotation comes from Calvin Tomkins, “Time to Think,” in Robert Wilson: The Theater of Images, 2d ed. (Harper and Row, 1980), 84. The Shklovsky quotation is in “Art as Technique,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. Lee T. Lemon and Marian J. Reis (University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 12. I say more about Shklovsky and narrative here.

True Stories.

Posted in Directors: Byrne, Film comments, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Independent American film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Pockets of Utopia: TRUE STORIES open printable version

| Comments Off on Pockets of Utopia: TRUE STORIES

Sunday | December 9, 2018

Kristin here:

Flicker Alley has once again made a great contribution to the recovery of silent cinema by releasing two restorations of films starring Mary Pickford.

Pickford was an extraordinarily successful figure of the era. Her enormous popularity as a star lasted from her days acting in Griffith Biograph films into the early sound period. She was one of the four founding artists of United Artists. Indeed, she was the new distribution company’s mainstay for a time, as her co-founders, Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Chaplin, and D. W. Griffith (seen above watching her sign the contract) worked off their commitments to other distributors or made films that were less than successful (notably Chaplin’s 1923 A Woman of Paris). After retiring from acting, Pickford strove to retain prints of all the films she had been in, hoping to guarantee their ultimate survival.

One of Flicker Alley’s two films, Little Annie Rooney (1925, dir. William Beaudine) was restored from a nitrate print in her collection, held at the Library of Congress. The other, Fanchon the Cricket (1915, dir. James Kirkwood), she and everyone else feared was lost. In 2012, however, the Mary Pickford Foundation discovered that the Cinémathèque française had a nitrate copy of Fanchon, and, with contributions from an incomplete nitrate print at the British Film Institute, a restoration was achieved at l’Immagine Ritrovata labs in Bologna. Both films come in a dual edition of DVD and Blu-ray, accompanied by new scores and program booklets. Both are region-free. The visual qualify of both restorations is excellent.

The two films are dramatically different from each other. Fanchon is set in 19th Century rural France, while Little Annie Rooney takes place in contemporary New York. Still, in each Pickford plays a wild young woman–young meaning almost child-like in her innocence and aggressive behavior–and yet one ready to step abruptly into romance and marriage.

Fanchon the Cricket

The origin of the film dates back to Georges Sand’s 1849 novel, La petite Fadette, written in collaboration with François le Champi. (“Fadette” apparently refers to a girl with fairy-like powers.) Set in the 19th Century French countryside, it marked Sand’s return to a focus on the rural poor. The novel was translated into English immediately and republished repeatedly with various titles in later translations, most recently in 2017.

In 1861, an English-language adaptation as a play, Fanchon the Cricket, by August Waldauer premiered in New Orleans to great success. (“Fanchon” roughly means someone who is free.) Its star, Maggie Mitchell, apparently the Pickford of her day, continued to tour in the role for over thirty years, still playing the teenage heroine into her 50s. She died in 1918 at aged 85 and thus may have seen Pickford play the role on the screen. (Numerous actresses had also starred as Fanchon in the popular play. There was a 1912 film version from IMP.)

Fanchon tells a remarkably unclassical story for 1915, a year in which the classical Hollywood style was well on its way to maturity. There is relatively little plot. The action takes place in an unspecified rural area of France in the 19th Century. Landry, the son of a rich local family, has become engaged to Madelon. During the celebrations, we are introduced to Fanchon, a waif living in the forest with her grandmother, who has a reputation as a witch. Fanchon is torn between her desire for friendship and her mischievous antagonism with the young people of the area, who fear her.

These young people seem perpetually to be celebrating the engagement or local saints’ days, venturing out into the forest for picnics and dances, despite the fact that they seem unreasonably frightened by Fanchon’s presence there. Repeatedly they encounter her, who deliberately tries to scare them, then awkwardly dresses up in her mother’s outmoded clothes and tries aggressively to join their frolics.

Despite Landry’s engagement, he is reluctantly drawn to her, especially when she saves him from drowning in a lake. Only late in the plot do we discover key premises. First, Fanchon’s grandmother had been forbidden to marry Landry’s uncle, her true love, which led her to her current hermit-like existence. Second, Fanchon, who has been actively luring Landry away from his fiancée, would never marry him without his father’s consent. These are things that a classically constructed plot would set up much earlier, creating tension that is singularly lacking in this film. Still, all ends well.

The film is almost entirely shot outdoors, in the fields, forests, and lakes of Pennsylvania, with resulting beautiful compositions (see bottom).

Pickford fans probably know that Fanchon the Cricket is the only film in which all three Pickfords played. Lottie is Madelon (above left), the petulant betrothed of the hero, Landry, and Jack plays a young bully whom Fanchon fights when she sees him tormenting Landry’s “half-wit brother” (above right).

Little Annie Rooney

The films begins with an expository title: “Up town a gang calls itself ‘Society’–down town a gang calls itself a ‘Gang’ and lets it go at that. –Let’s go down town!” The opening scene then shows two groups of kids caught up in a street fight. The whole thing is comic, if pretty intense, and its only female participant is Annie Rooney, apparently a youngish child, played by Pickford. Her allies are an ethnically diverse bunch, including Abie Levy (above, played by Spec O’Donnell, who played so many mischievous-son roles in Max Davidson’s Jewish comic shorts of the 1920s). Pickford called her young cast a “mini League of Nations.” These youngsters are more than background decoration, with some of them having roles to play in the action, as when Abie’s family comforts Annie after her father is shot.

Although the opening part of the film is typical Pickford comedy, there are grown-up gangs in the plot as well, with Annie’s brother drawn into bad company, despite their widowed father being an Irish cop. Indeed, the narrative shifts into what is nearly a Von Sternberg film. There’s an atmospheric scene in a dance-hall where the father is gunned down by a lurking thug and Annie’s love interest (turns out she’s not as young as her behavior would suggest) gets blamed because he happens to be standing by Rooney at the time.

The lighting in these and other shots is impressive–not surprisingly, given that Pickford was very particular about the photography for her films. Her regular cinematographer, Charles Rosher, was one of the tops in the field during the silent era. Hal Mohr assisted, and the results beautifully employ the three-point lighting system developed during the late 1910s and 1920s.

Little Annie Rooney was a success, showing that Pickford could lure in the audience with her accustomed youthful comedy and then transition into a more serious plot that showed off her dramatic abilities as well.

Flicker Alley’s press announcement states that these two releases are the “first of a planned series of Mary Pickford films that showcase the breadth and depth of her talents as well as that of the finest behind-the-camera craftspeople of the time.” Given Pickford’s prolific output, one can only hope that this series goes on and on.

Fanchon the Cricket

Posted in Film comments |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Pickford times two open printable version

| Comments Off on Pickford times two

Monday | December 3, 2018

Interstellar (2014).

DB here:

A new edition of our e-book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages has just gone into production at the hands of our web tsarina Meg Hamel. It updates our discussion of Nolan’s career by including a brand-new chapter on Interstellar and one on Dunkirk that revises and expands our blog entries on the film (here and here).

The book also includes a new chapter surveying Nolan’s approach to filmic storytelling, along with more links and frame enlargements. I wrote the bulk of this second edition, with Kristin contributing portions on exposition in Inception and Dunkirk.

As in the first edition, I try to respond to the objections that some viewers have about Nolan’s work. I grant some problems with his films, chiefly at the level of visual style. But I also try to make a case that Nolan has been exploring film narrative in ways that are significant for film history. I argue that his achievement contributes to storytelling trends of his moment (from the 1990s on) and in art and literature more generally. His work is shaped by what I call a “formal project,” akin to that we find in Alain Resnais and Hong Sangsoo.

Nolan’s detractors are likely to counter that those directors are better than Nolan. But they work in different circumstances. In the context of mass-audience Hollywood cinema, I think Nolan’s work repays scrutiny.

I’m mostly offering analysis, not evaluation. I have to admit, though, that in reworking the book and rewatching the films, I’ve come to extend my admiration for certain projects (The Prestige, Dunkirk) to others, especially Interstellar. Still, even if you don’t share my regard for the films, I think that it’s worth discussing what Nolan’s accomplishment shows about trends in modern cinema and the broader possibilities of filmic storytelling.

Which is to say, yet again, that Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages 2.0 is primarily a venture in film poetics.

We hope to make the new edition available this month or in January. It would be priced higher than the current edition, at $3.99 (i.e., the cost of a Tall Caramel Frappucino). This pays for a new design for the book, one exploiting the horizontal format for widescreen frame enlargements. We won’t be embedding video extracts in the text, as we did last time, but we may set up the clips as online links.

To the hundreds of you who bought copies over the years, thank you. We appreciate your support, and we hope that the new edition will also be worth the attention of the readers who visit this site.

Just to be clear, we’ve also welcomed the narrative explorations of Resnais and Hong Sangsoo on our website, and in our research more generally.

Interstellar (2o14).

Posted in Books, Directors: Hong Sangsoo, Directors: Nolan, Directors: Resnais, Poetics of cinema |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Christopher Nolan: Back into the labyrinth open printable version

| Comments Off on Christopher Nolan: Back into the labyrinth

|

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.