Monday | September 10, 2018

As I Lay Dying (2018)

Kristin here:

As Variety‘s Nick Vivarelli pointed out earlier this week, Arab cinema is well represented here at the Venice International Film Festival. The same is true of Middle Eastern films in general. I couldn’t catch all them, but here are some thoughts on those I saw.

The Palestine question as sit-com

Comedies about ethnic hostility in Ramallah are understandably rare. For a long time the only one I knew of was Elia Sulieman’s masterly Divine Intervention (2002), though there may be others. Now we have Sameh Zoabi’s Tel Aviv on Fire, a real crowd-pleaser playing in the competitive Horizons section of the festival, a section designed to showcase promising early-career filmmakers.

Despite the title, which might suggest a grim tale of conflict, perhaps involving terrorism, the film is very funny. “Tel Aviv Is Burning” is the name of a daily melodramatic TV series made in Ramallah by a group of Palestinians but enjoyedby both Jewish Israelis and Palestinians–mostly women. (All citizens of Israel are considered Israeli. This means that, ironically, the Israeli Film Fund is required to provide funding to Palestinian projects; it is one of Tel Aviv on Fire’s backers.) The story arc is at a point where a Palestinian woman is assigned to disguise herself as Jewish in order to seduce an important Israeli general and get a key to a hiding place for military plans.

Salam, the protagonist (played by Kais Nashif, who won the best actor award in the Horizons competition), is the lowly nephew of the show’s producer, fetching coffee and helping keep the Hebrew dialogue authentic. Suggesting a bit of action one day, he is promoted to be a writer, despite having no experience or skill. When Saam is stopped for no reason at an Israeli checkpoint (above), he meets a general, Assi. Salam boasts about being a writer on the show, which happens to be a favorite of Assi’s wife. Hoping to impressive his shrewish spouse, Assi puts pressure on Salam to slant the story: the heroine should fall in love with and marry the Israeli general she has seduced. Eager to get away, Salam agrees.

The rest of the story is a cleverly scripted series of twists as Assi makes further demands to make the Israeli general more sympathetic and Salam tries to foist these on his reluctant collaborators. One might argue that the final surprise revelation does in fact make the film lean toward the Israeli side. On the whole, though, Zoabi’s film balances the two factions and manages to convey that the ongoing conflict is absurd, given the many similarities between the two main characters and the universal appeal of “Tel Aviv on Fire” across Israel’s population.

One strength of the film is the stylistic contrast between the main story’s conventional lighting and location shooting and the tacky sets, garish colors, improbable dialogue, and over-the-top performances in the scenes from the TV series.

A microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Veteran Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai contributed a program of two films to the festival. The first was a short, A Letter to a Friend in Gaza, the second the feature A Tramway in Jerusalem, both playing Out of Competition.

A Letter to a Friend in Gaza is a evocation of the bitter disagreement between people, even within families, using a text by Albert Camus to sum up the issues in poetic form. I suspect one would need to know a great deal about the Palestinian occupation to fully grasp this oblique work.

The issues are readily apparent, however, in A Tramway in Jerusalem. Set aboard a tram, with occasional shots on platforms where it stops, the action consists of a series of short scenes between a wide variety of citizens. The episodes are separated by titles announcing the time of day, but these skip about, suggesting that this is not a day-in-the-life-of a tram tale but a series of random encounters. The vignettes are not connected, though a few characters recur, most notably a French tourist introducing his beloved Jerusalem to his son. The participants in these short scenes are played by actors, though the only one likely to be recognizable to a broad audience is Mathieu Amalric as the tourist (above).

The scenes suggest a range of possibilities for successful or failed coexistence. For no reason but prejudice a woman accuses a Palestinian man standing next to her of sexual harrassment, and the guards on board immediately throw him to the floor. Two sophisticated young women, one Palestinian with a Dutch passport, the other an Israeli, are standing side by side. They chat casually, clearly very much alike, and when, again for no reason, an aggressive guard demands the Palestian’s passport, the Israeli stands up for her. In an overly long episode, a Catholic priest soliloquizes about the death of the three religions struggling for dominance in their mutually sacred city. The French tourist, determined to idealize Jerusalem, fails to realize that a local couple is poking fun at him by enthusiastically advocating the violent suppression of Palestinians.

The Iranian search narrative endures

Not all Iranian films involve searches by any means, and yet searches, whether they involve a journey or not, provide the structure of many familiar classics like Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Mirror. By chance, two films at this year’s festival show searches involving in one the beginning of life and in the other its end.

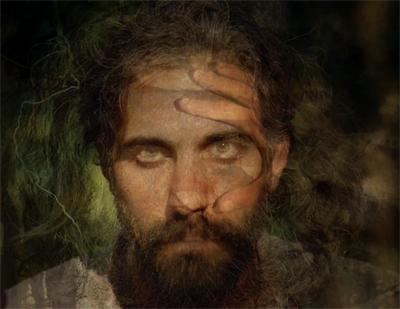

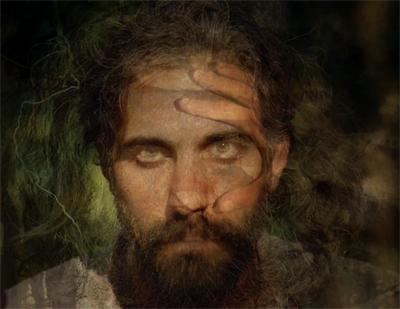

Mostafa Sayari’s first feature, As I Lay Dying (Hamchenan ke Mimordam), also played in the Horizons competition. It begins after the death of an old man. One of his sons, Majid, who has cared for him recently, admits to the doctor that he had provided the sleeping pills that apparently killed his father, but the doctor agrees not to mention this on the death certificate. A hint that the time of death is not known provides the first clue in a subtle mystery. Further clues surface in the course of a psychological drama among the four siblings who assemble to drive their father’s body to a small, distant village for burial.

As the journey continues and quarrels develop, the siblings question Majid as to why he chose this remote village for the burial. The length of time that the father has been dead emerges further as a significant factor. By the end, the answers to the three siblings’ questions becomes apparent to them.

Speaking with others who had seen the film, I heard complaints that the story was difficult to understand. I think that As I Lay Dying is something of a mystery story, without being strongly signaled as such, and that sufficient clues are dropped along the way that the viewer should be able to understand the situation by the time the story ends, rather abruptly and perhaps seeming not to offer a resolution. (It would help to know that Muslim burials are supposed to take place as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours.) Certainly nothing is made explicit at the end, though again, an attentive viewer should figure out the implied outcome.

The film takes place largely on a bleak desert road, including some beautiful widescreen compositions reminiscent of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s work in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, perhaps coincidentally also involving a search in the desert, in that case for an already buried body. (See top.)

The search narrative goes back at least as early as Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (Khesht O Ayeneh, made 1963-64, released 1966). It was one of the historically important films shown in the “Venice Classics” series of recent restorations.

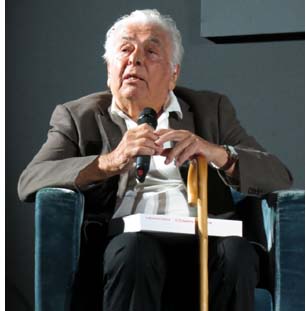

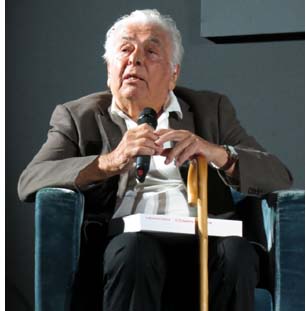

Brick and Mirror is generally considered the first Iranian art film, having come out three years before Dariush Mehrjui’s classic, The Cow (1969). Golestan was an experienced filmmaker, mostly of documentaries, but Brick and Mirror was his first fiction feature.

The title has nothing to do with the subject matter of the film but is more evocative, being, as Golestan has revealed, derived from a Thirteenth Century Persian poem: “What the Youth sees in the mirror, the Aged sees in the raw brick.” The word “brick” here does not refer to the familiar fired brick, which costs money to buy, but to the simple mud brick, widely used by the poor across the Middle East, since anyone with access to silt and a simple wooden frame can make them.

The story begins one night as the taxi-driver protagonist, Hashem, discovers that a woman passenger has left a baby in the back seat of his car. In a famous scene, he wanders the desolate neighborhood searching for her (see below). Eventually his girlfriend joins him in his apartment to help care for the child. The experience leads her to hope that they can marry and raise the child themselves, turning their so-far aimless affair into a family. The quest to find a practical, humane way to dispose of the baby–or not–takes up the rest of the film. Near the end, a lengthy scene of babies and young children in an orphanage reflects Golestan’s documentary experience.

The new print recalls the rough, often dark look of black-and-white widescreen films of the 1960s, especially those of the French New Wave. Golestan’s story of fruitless wandering and unresolved relationships has been compared by some critics to the films of Antonioni, and it seems clear that Antonioni’s work and other European films of the 1950s and 1960s influenced him. There are, however, distinct differences. While Antonioni deals with the psychology of bourgeois characters (except in Il Grido), the couple in Brick and Mirror are working-class, and their problems are caused as much by their social situation as by any general ennui.

Remarkably, Golestan was present to introduce the film. At 97, he remains articulate and charming. He primarily sketched out his early career and the inspirations for Brick and Mirror. The most interesting point concerned a startling moment during the early scene of Hashem searching the dark neighborhood for the elusive mother of the baby. A close composition of him at the top of a long stairway suddenly leads to a quick series of axial cuts, each shifting further back until he is seen in extreme long shot. The moment reveals the empty staircase and emphasizes the hopelessness of the chase. Golestan emphasized jump-cut quality of the passage and mentioned that he had not seen Breathless at the time Perhaps the moment harks back further, to the axial cuts of static figures used in Soviet films of the 1920s and the work of Kurosawa.

Previously only incomplete, worn prints of Brick and Mirror were available, and then only in rare screenings. The importance of this restoration was emphasized by the festival’s publication of a short book, Brick and Mirror, which brings together a number of essays by Golestan and others. It also describes the restoration, done with the director’s cooperation and accomplished at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in Bologna. My thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with a copy and more generally for his important work in reviving Iran’s film heritage, including programing the Iranian season at Bologna that I reported on in 2015.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more photos from this years Mostra, see our Instagram page.

[September 12: Thanks to Steve Elsworth for some corrections.]

Brick and Mirror (1966).

Posted in Festivals: Venice, Film comments, National cinemas: Iran, National cinemas: Israel |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018: The Middle East open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018: The Middle East

Friday | September 7, 2018

Press conference for Biennale College Cinema and VR.

DB here:

As happened last year, I was invited to participate in the Biennale College Cinema Panel. This was the seventh year of the program, which supports the making of low-budget feature films by young people. Proposals, numbering in the hundreds, are reviewed, and out of those several projects are developed in workshops. After development, three projects are chosen for funding, to the tune of 150,000 euros each. You can read details of the program here.

It’s remarkable how much these filmmakers manage to do on this budget. Both last year and this year, I was impressed by the ambition and panache displayed in the films. None of the directors or producers are novices; many have extensive experience in media. Still, to make a feature is a massive accomplishment, and the flair and professionalism on display in the trio of films was heartening.

I was lucky to join a team of pros. Under the direction of Peter Cowie and Savina Neirotti, our group included Glenn Kenny, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, Chris Vognar, and Stephanie Zacharek. Our task was, refreshingly, not to award prizes but simply to offer responses to the finished works. All these writers are steeped in modern and classic cinema, and they’re eager to share their experience with new talent.

One theme that emerged from our public session was the idea that all three films emphasized the slow revelation of character over rapid, audience-engaging plots. Very much in the tradition of European “art cinema,” they aim to entice us with intriguing, sometimes mysterious and contradictory individuals. We watch those individuals confront situations in which their personalities can be revealed or can undergo change. So the filmmaker’s problem becomes: How to create drama out of character?

Into the woods

The most mythlike film was Yuva, by Emre Yeksan of Turkey. We’re plunged into a lush forest landscape, and in extreme long shot we glimpse a shaggy figure bearing a carcass (pig? dog?) into an opening guarded by fallen branches. Is it a shelter, or a passageway to another realm? Both, as it turns out.

Without the familiar signposts–no backstory, no titles identifying time or place–and confronting a wordless protagonist, we’re obliged to pay attention to details of what we see and hear. As in many character-centered films, dramatic buildup is replaced by details of daily routines. In this case, our protagonist Veysel explores the forest, finds a stricken bird he tries to revive, and–now traditional drama starts–spies uniformed guards on patrol.

Another film would have started by showing logging companies slashing their way through the forest, immediately establishing a conflict. Here, we’re given the guards, the whine of a woodchipper offscreen, the thrashing of helicopters above, and anonymous hands painting red X’s on trees to be felled. We have to conjure up a drama out of fragments. Even the closer shots tend to keep the landscape on our minds, not least in hallucinatory images.

As the film goes on, we see Veysel slapping mud over the red crosses while evading the patrols. We meet new characters: a stricken woman Veysel carries to the secret shelter, and his brother Hasan, who has come to take him away because the mysterious patrolmen say “they’ll kill you if you don’t leave.” So suspense eventually emerges, but always subordinate to the concrete spectacle of mysterious behavior on the part of our protagonist. The climactic revelation of where that burrow leads pushes the film to a more mystical level. Yuva‘s enigmas of characterization are in the service of broader themes about sanctuary and rebirth.

Born in a cemetery

If Yuva is a landscape-based film, Deva, by Hungarian director Petra Szöcs, is more of a portrait. True, the title refers to the town in Romania where the action occurs, but it concentrates on Kato, a teenager with albinism who is adjusting to life in an orphanage.

Again, character emerges from routines. On her “free day,” Kato shops and smokes and experiments with harsh makeup. She also surprises us. “I was born in a cemetery.” “I killed a boy because he mocked me.” We assume she’s displaying bravado, but either way she engages us as a person before any highly dramatic action is launched.

Still, a plot does develop, centering on Kato’s relationships with her caregivers, infused by her belief in her magical powers. When the attractive and sympathetic Bogi joins the orphanage staff, Kato is drawn to her, and Bogi befriends her–to the point of allowing an indiscretion that will jeopardize their relationship and Bogi’s job. Kato also helps mastermind a piece of mischief that will discredit Anna, a less popular teacher.

Yuva favors distant shots and long takes, but in Deva, Szöcs relies on tight framings and layers of depth (often out of focus) to fragment her scenes. Faces and dialogue are often kept offscreen, the better to concentrate on Kato’s fascinating face and gestures.

Deva‘s laconic style itself becomes a source of curiosity for us, as bits of connective tissue are left out and we’re obliged to appraise the changes in Kato’s character. Our curiosity is enhanced by the performance of Csengelle Nagy as Kato, which is riveting in its sobriety and contrasts with the warm and extroverted Boglárka Komán in the role of Bogi. Again, narrative engagement emerges from the mysteries of personality rather than the pressures of an external situation.

On ice

I know it sounds too neat, but to some extent the landscape and portrait impulses find a balance in Zen in the Ice Rift, directed by Margherita Ferri. The action takes place in the majestic, somewhat menacing Italian Apennines, where Maia, nicknamed Zen, lives with her mother. As the only girl on the ice hockey team, Zen is mocked as a lesbian, and she has become hardened to the bullying she encounters. With her butch-flip hairdo and perpetual frown, she has a hair-trigger temper and all but begs people to fight with her.

One screenplay stratagem for gaining audience sympathy is to have your protagonist treated unfairly. This happens early on, when Zen is slammed by a player on the ice. She reacts by firing a BB pistoal at her loitering teammates. They get payback by locking her neck to a railing. Voilà: a sympathetic but imperfect protagonist, someone we can watch with keen interest as she must make decisions, bad or good.

Those decisions include accepting overtures of intimacy from Vanessa, the prototype of the beautiful, popular teenager. Zen’s sexual identity, confused from the outset, becomes the focus of the drama. This process develops in unexpected directions and leads to a climax that exhibits how teenagers’ use of social media can take bullying to a brutal level.

When Zen’s coach tells her at the beginning that she had a chance to try out for the national woman’s hockey team, I briefly thought we were going to get a sports film, in which the protagonist undergoes the rigors of training and the test of competition. No such thing. The focus is on Zen’s place in the world of teenagers. Her hockey talent is one part of her personality, not the source of goals and conflicts and ultimate triumphs, let alone “life lessons.”

Yet the sports element isn’t gratuitous. Ice becomes a metaphor in the course of the film, as insert shots show glaciers cracking while Zen is forced to confront her still-developing identity. At the end, when she takes to the rink in a burst of solitary confidence, we realize that her defiance hasn’t diminished. Zen in the Ice Rift shows how the drama of character can unfold in both a social setting and the larger milieu.

In addition to the feature films at the Biennale College, there were four Virtual Reality projects associated with the program. The three I saw explored aspects of VR as a medium: awkward intimacy in Metro Veinte, the sense of sinister enclosure in Elegy (aka VRtigo), and the possibility of sampling an eerie landscape in Flood Plain, which extends the narrative situation and imagery of Yuva. At the same time, I thought that they would have made interesting films–which probably indicates that I see rather close affinities between VR and cinema.

Major differences, of course, include VR’s absence of a frame and the possibility of self-willed exploration. As members of our panel suggested, VR creators will need to find ways to motivate the presence of an onlooker in the virtual space, and, if storytelling is the goal of a project, to guide the viewer to salient elements. Narrative, we’ve known since forever, depends on controlling attention.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale. Thanks also to my colleagues on the panel for lively movie talk throughout our stay.

Last year’s College visit is discussed here, and my earlier journey into VR here.

Make the world go away: Venice Biennale VR theatre at Lazzaretto Vecchio.

Posted in Festivals: Venice, Film comments, Virtual Reality |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018 College cinema: Landscapes, portraits open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018 College cinema: Landscapes, portraits

Tuesday | September 4, 2018

DB here:

The Venice Biennale film festival unveiled to a panting cinephile public the long-rumored Welles film The Other Side of the Wind, now reconstructed thirty-three years after its director’s death. This is only one of many possible versions. Welles reportedly edited two scenes himself, including an erotic encounter in a rainstorm-shaken car, but the rest has been assembled from about a hundred hours of footage. (But see the PS in the codicil below.) Welles left many notes but no definitive script, so editor Bob Murawski, with guidance from many Welles experts, has carved out something that must stand as a best approximation what its initiator had in mind.

Approximation is also the word for my response. I need to see the film more than once in order to get to grips with it. Not that it’s a dense, complex work; I don’t think it is. It’s just that I need to shake off a sense of déja vu.

Or rather, déja lu. Having read about the film for years, I found almost nothing onscreen that I hadn’t been primed for by press coverage, by Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, and by Josh Karp’s Orson Welles’s Last Movie. I found myself groping for a triple vision: How to imagine seeing the film fresh, without knowing its plot, characterization, and most pungent lines already? And then, how would it have looked and felt in the context of 1970s filmmaking? Finally, of course, how to consider it now, in the context of modern cinema?

Sorry, but I’m far from having an answer to any of these questions. Herewith, just some things that the film made me think about.

All together now

One persistent narrative premise, on stage and screen, might be called the climactic gathering. The plot is concentrated in a limited space and a short span of time–a day, or better, a night. The occasion is a meeting or party that brings together friends, acquaintances, associates, or kinfolk. As time passes, quarrels break out, old wounds rip open, and eventually family secrets and past transgressions are exposed. Examples of this dramaturgy are O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and films like Twelve Angry Men, A Wedding, Margin Call, and The Celebration.

The advantages of this format are many. The limits of time and place realistically assemble characters for intense confrontations, and those can be interwoven quickly to maintain audience interest. Actors like such a setup because the deterioration of civility that usually comes with the situation allows them to show a range of emotions that will culminate in bravura breakdowns. But the disadvantage is a certain obviousness: the secrets or suppressed feelings or traumatic memories will have to be stated rather nakedly. Subtlety may not be easy to achieve.

The Other Side of the Wind situates the climactic-gathering format in Movieland. After filming a stretch of director Jake Hannaford’s work in progress, called The Other Side of the Wind, cast and crew and hangers-on drive out to his house. The party aims to celebrate his seventieth birthday and, perhaps, enable him to drum up finishing money. A night of uninhibited drinking and verbal sniping is broken by screenings of parts of Hannaford’s film. At the climax, Hannaford drives away to a fatal car crash.

Welles, being Welles, puts new twists on the template. In Reinventing Hollywood, my book on 1940s cinema, I argued that he, like Hitchcock, was under unusual pressure to keep coming up with new ideas. Both filmmakers were so widely copied that they had to outrun their imitators. As Welles told Gary Graver, his loyal DP in his late years:

Somebody always has to be ahead of everybody else. I have to be steps ahead of everybody. I have to be more inventive and do things that nobody has done.

His urge to innovate helped fuel the fifteen years he devoted to shooting and cutting The Other Side of the Wind. This jaundiced satire of Hollywood displays some striking formal strategies–some original for the period, some familiar from his other work, but all an effort to galvanize audiences as he had throughout his career.

A man’s man

This Hollywood party is rendered in blunt satire and in-jokes. It’s haunted by Mr. Pister (Joseph McBride), a geeky film critic asking questions about phallic symbols and the camera’s quest for reality. A more acerbic critic, Juliet Riche (Susan Strasberg), is a stand-in for Pauline Kael, who wrote a notorious broadside against Welles. Peter Bogdanovich plays the implausibly named Brooks Otterlake, a younger, successful director who is both a disciple of Hannaford’s (he calls Jake “Skipper” and “Daddy”) and a rival to him. Familiar faces from the studio years–Paul Stewart, Dan Tobin, Mercedes McCambridge–as well as younger figures like Paul Mazursky and Henry Jaglom make appearances. This climactic gathering brings together New Hollywood and Old, even Elderly, Hollywood.

By casting John Huston as the lanky, roguish Hannaford, Welles adds an evocative layer to the citations. Welles had acted in several Huston films; now Huston is in front of the camera, his face resembling, in Dwight Macdonald’s phrase, a relief map of the Dakota badlands. He was nine years older than Welles, but he made his directorial debut with The Maltese Falcon in the same year as Citizen Kane. Significantly, his star rose after Welles’s fell. By the time Huston won acclaim with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Welles was unemployable as a Hollywood director and scrounging work in Europe.

Karp reports that Welles told Huston that his role was a critique of all egotistical directors—“It’s about us, John”—and Welles considered playing the part himself. But Welles wouldn’t have fit the more specific target the film seems to home in on, the swashbuckling filmmakers like Rex Ingram, Howard Hawks, and William Wellman. Huston embodied the hunting-shooting-fishing-punching persona to the full. In this context, Riche’s suggestion that Jake Hannaford harbors gay desires for his male stars takes on a special bite.

Was Welles taking jabs at Huston’s image? I have to wonder. While Welles was fleeing hotel bills and performing offhand magic on talk shows, Huston maintained an active studio career; he took leave from Other Side to make one of his biggest successes, The Man Who Would Be King (1975). At the least, Hannaford’s climactic gathering can be seen as another sort of convergence, bearing the traces of the contrasting 1970s fates of two prodigious directors who came up together.

Cameras and cutting

The notion of tracing a day and night in the lives of several movie people was sharpened by Welles’ decision to shoot The Other Side of the Wind in a reflexive cinéma-vérité style. Today we accept a grab-and-go documentary look as a legitimate approach to fictional presentation, but in Other Side the technique is given a realistic pretext. Anticipating the premise of The Office and other TV shows, Welles’ innovation was to provide specific sources for everything we see and hear: an array of cameras and tape recorders. Here even intimate exchanges are captured by at least one camera.

In a way, this idea reverts to Welles’ lifelong interest in the how of storytelling. His radio plays, under the rubric “First Person Singular,” often framed their stories within a narrator’s commentary. This Conradian inclination toward embedded tales, brilliantly managed in his Mercury radio adaptation of Dracula, emerged as well in Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. Other Side’s mosaic of scenic bits harks back to the montage of sources (dance music, government announcement, network news bulletins, voice-over diary entries) that fill the War of the Worlds broadcast (1938).

Like Kane, Other Side opens with the main action already completed. An image of a crumpled car is accompanied by Bogdanovich/Otterlake’s voice explaining that Hannaford died in a crash after his party. (Apparently, Welles would himself have supplied this narration.) That explanation frames the footage that has been assembled documenting Jake’s last day on earth. Embedded in all that material, mostly black and white and in 4:3 format, are scenes from Hannaford’s last movie, in ripe color and widescreen and full of arty compositions and one frequently naked lady. Although they’re motivated as being projected to various audiences in the film, at the end some of the imagery seems to float free, being intercut with the documentary material.

The result is an extended experiment, more radical than even Rear Window, in the Kuleshov effect. Cuts between cameras and partyers, or people in conversation, are linked solely by our understanding of the context; there are few establishing shots. The cuts link shots that were made months or years apart, in any of the many houses Welles commandeered as his sets.

Admittedly, he had been up to such tricks before. The instructive documentary They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead (also screened at Venice) shows an example from Othello of shot/reverse shot cutting based on vast gaps in production time. But Other Side‘s shifting cast and locales have created Welles’s most disjunctive, fragmentary film. I counted about 2300 shots in 117 minutes, an average of three seconds per shot. He applied the same approach in F for Fake (1973), but that feels less scrappy because Welles’s buoyant voice-over glues everything together.

On this blog we try to practice a criticism of enthusiasm, writing mostly about films we admire and avoiding panning the films we don’t. Still, as a lifelong Welles fan, I can’t duck an initial appraisal.

I confess being disappointed by the film. I’m not ready to call it The Other Side of the Windbag, but I’m not sure it escapes the on-the-nose quality we often find in the climactic-gathering format. Here people must get both nasty and horribly transparent about baring their feelings. Moreover, the film-within-the-film, shot in glowing color and abstract cityscapes, is supposed to be a parody of Antonioni (Zabriskie Point in particular), but (a) most of it is more like a slick-magazine version of a trance film from the 40s like Meshes of the Afternoon; and (b) it’s inconceivable that even in the Love Era Hannaford’s project could receive commercial funding or release. It seems to me a bad idea of what a bad movie looks like.

Still, I’m trying to keep an open mind. Watching it more analytically and reading what critics write about it may open it up for me in ways I can’t now predict. For the moment, it’s satisfying enough to thank Netflix for enabling us to see in however hypothetical a form, what forty years’ fuss has been about.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome of us to this year’s Biennale. I’ve especially enjoyed discussing The Other Side of the Wind with Peter, whose The Cinema of Orson Welles shaped my view of the director’s career way back in 1965.

My quotation from Gary Graver comes from Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, p. 225.

For more on the Kuleshov effect, see “What happens between shots happens between your ears” and “They’re looking for us.”

Feel free to visit our Instagram page for an ever-expanding set of snapshots of the Venice festival.

P.S. 5 September 2018: Standard accounts suggest that Welles completed editing only two sequences. Alert reader Evan Davis points out that editor Bob Murawski says that Welles edited about 30% of the finished film. Thanks to Evan for this.

I apologize for the typos and whiffs in this entry; we’ve had unreliable access to the Net lately, and not all revisions took.

P.S. 8 September 2018: Ardent Wellesian Jim Naremore has created his own website, and it’s must reading for every cinephile. Right off the bat he gives us a thoughtful piece, “Orson Welles, Citizen of the World,” available in English only online. Watch for Jim’s essay on The Other Side of the Wind, slated to be published in Cineaste.

John Huston, Orson Welles, and Peter Bogdanovich on the set of The Other Side of the Wind.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Directors: Huston, Directors: Welles, Film comments, Readers' Favorite Entries |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018: Welles and THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018: Welles and THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND

Sunday | September 2, 2018

Roma (2018)

Kristin here:

The Venice International Film Festival has a way of making the time fly–despite the occasional feeling when standing in line for a film that the doors will never open. It seems ages ago that we saw the early-morning press screening of First Man, and yet a mere three days have passed.

So far we’ve had the rare experience of each morning seeing another exciting, excellent, thoroughly satisfying film: First Man (which David has already written about), Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, and the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Can this last? Probably not, but the rest of the program offers rewarding films and so far seems to justify journalists’ claims that this year’s festival is boosting its already growing reputation.

A new (and laudable) tradition?

Last year we reported on the restored print of Lubitsch’s 1923 Rosita, which played on the evening before the official start of the festival, accompanied by an orchestra playing a restoration of the original score, edited and conducted by Gillian Anderson. This year the festival organizers followed up on that success by premiering the restored Der Golem (Carl Boese and Paul Wegener).

The large and enthusiastic crowd showed that, given the right presentation, this old film can attract those who think of the festival primarily as a place to see brand-new films before the rest of the world does. In fact, there’s also a healthy restoration thread running through the festival, though silent films tend not to figure in it.

Der Golem is noteworthy as one of a small number of relatively sympathetic Jewish-themed films that came out in the early to mid-1920s in Germany. (I recently wrote about this trend and the newly restored Der alte Gesetz.) It does not manage entirely to avoid stereotypes, but it should be pointed out that the Christian characters come across far worse.

Der Golem is an early entry in the German Expressionist film movement of the 1920s, having come out in 1920, the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. Rather than using painted flats to create a stark, graphic look, as Caligari did, Boese and Wegener’s film features the droopy-clay look employed by Hans Poelzig, perhaps the finest of the Expressionist architects of the day. The result is that the clay buildings of the ghetto and the clay Golem seem at times to merge into each other.

The print looks much better than previous copies available. The Belgian Cinematek held an original negative, thought to be the one for German distribution, rather than the second negative shot for foreign distribution. Prints held in other archives supplied missing footage, as well as tinting and toning information and the graphics for some of the intertitles. The drop in clarity is apparent in the replaced passages, which, interestingly, include the sequence in which Rabbi Löw summons a demon to give him the magical name that will bring the Golem to life. Why this key moment was removed from the negative will probably remain a mystery.

The musical accompaniment was a modern composition by the six members of the Mesimér Ensemble. It fits the current fashion for highly dissonant scores, including the seemingly de rigueur vocal passages. It went well with the film.

I hope the festival organizers will continue this tradition of presenting restored silent films with musical accompaniment as a prelude to the festival. It makes for a relaxing transition into the more film-filled days to come.

Worth waiting for

After the critical and commercial success of Gravity (2013), which I wrote about here and here, there has been much curiosity about Alfonso Cuarón’s long-anticipated next film, Roma. Advance word had it that the film was to be shot in Mexico and in Spanish.

As I’ve already suggested, the film is splendid, and its black-and-white, widescreen images looked great on the huge Salla Darsena screen (from front row, center, of course). As with Zama last year, at the end David asked if we had just seen a masterpiece. Again neither of us had any doubt that we had.

The film may be based on Cuarón’s childhood memories, but it is hardly autobiographical. Instead the protagonist is Cleo, one of the indigenous maids who work for the upper-middle-class family whose dramatic arc parallels her own. Conventionally the maids Cleo and Adela would be present in the backgrounds of scenes or at best be supporting characters. Instead Cleo is our identification figure. Indeed, of the four children of the family, three of them boys, we never have a clue as to which one might represent the director.

The double plot revolves around two desertions. First the husband and father of the family departs on an ostensible trip to a conference in Canada, which is soon revealed as a cover for his leaving his wife for another woman. AT the same time, Cleo is dating a man who professes to love her but who deserts her the moment she reveals she is pregnant.

One might expect this sympathetic tale centered largely around Cleo to center on the family’s harsh treatment of her. Instead, the cruelty is muted and casual. The children clearly adore her, and she them, and the wife says at one point that she loves Cleo as well. Far from firing Cleo upon learning of the pregnancy, the wife comforts her, pays for medical treatment at the family’s hospital, and buys her supplies that she will need. Yet the unkindness is apparent as well. The wife curtly tells Cleo to clean up the dog turds in the courtyard–the accumulation of which provides a running gag. She also carelessly leaves Cleo, who cannot swim, to watch the unruly children at a beach with dangerous waves. This unreasonable demand precipitates one of the film’s most dramatic scenes, shot in an excrutiatingly suspenseful long take.

Cuarón directs with his usual utter control and flair. The film is set in 1971 (when the director would have been ten years old), and the period details are impeccable–especially the family’s Ford Galaxie, which provides a running gag whenf characters try to maneuver it into a narrow garage.

There are the expected long takes and camera movement. One fast tracking shot races along the middle of a busy street, keeping up with Cleo and Adela as they run joyously along block after block to enjoy their time off (top). In another scene, the camera wanders around the upper floor of a furniture store as Cleo shops for a crib, only to end with a pan to the windows and the revelation of the street below full of rioters.

In the ongoing controversy over Netflix’s reluctance to release its productions in theaters, it is particularly ironic that it should be the studio to produce Cuarón’s big-scale film. The promise is that it will be released “in select theaters.” If you live near one of those, don’t miss it.

Socialist Realism lives on

I had hopes of medium height that Mike Leigh’s Peterloo would live up to his previous historical films, Topsy-Turvy (1999) and Mr. Turner (2014). It turned out that Leigh had taken on a project with nearly insuperable obstacles.

While Topsy-Turvy had Gilbert and Sullivan, with its musical numbers and the innate drama of the pair’s occasionally testy relations, and Mr. Turner had painting and a single eccentric personality to focus on, Peterloo is about radical politics. The Peterloo massacre of 1819, which perforce occurs only in the climax of the two-and-a-half-hour film, is a major incident in the history of British radicalism and reform, and it is relatively well-known to the citizens of Great Britain. Elsewhere audiences are likely to be unaware of it.

As a result, Leigh must present a great deal of exposition about the issues and the lead-up to the peaceful protest march at St. Peter’s Field in the Manchester area. The exposition takes the form of a long series of speeches and conversations about those issues. The speeches are largely taken from the historical record, and they impart a great deal of authentic historical information, but they frequently overwhelm the drama.

Many of the speakers are historical characters, about whom we learn relatively little. Leigh humanizes the situation by focusing at intervals on a single poverty-stricken family whose adult men work at the local weaving mills and face dwindling wages from the mill-owners.The opening is clearly intended both to provide a bit of violent action as a hint of things to come, much later, and to introduce us to a young bugler who belongs that poverty-stricken family. We follow his trek home, his arrival there, and, briefly, his fruitless search for work.

If we expect him to become an active protagonist, however, we are disappointed, for he recurs only occasionally and passively thereafter. Instead we move around the various occasions on which speeches are given to rouse the downtrodden population to action. It must, after all, be plausible that roughly 70,000 people from the area would assemble in Manchester for a peaceable demonstration for the vote and representation in Parliament.

The local politicians who attempt to thwart the protest and possible resulting violence are portrayed as old, ugly, and nearly hysterical in their mingled fear of and contempt for the working classes. Their fears aren’t entirely unreasonable, given that the Luddite movement of 1812 led workers to destroy the labor-saving automatic looms and occasionally the factories that held them. Violence had killed people on both sides of the struggle. Leigh perhaps hints at the “machine-breakers” in his shots of the vast mill interior (above) and some of the dialogue, but only someone familiar with British history of the era would link the Peterlook protestors to the Luddites.

The result somewhat resembles the Soviet Socialist Realist films of the 1930s and 1940s, with their noble peasants and caricatured bourgeoisie and government officials. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, exactly, but the Soviet films seldom tried for actual realism, and Leigh cannot entirely give up his passion for naturalism. The result is an uneasy mixture in Peterloo‘s tone.

Despite its faults, the film is impressive. Produced, again ironically, by Amazon, the film has what must have been Leigh’s biggest budget to date. Authentic costumes have been created for actors and extras enough to at least suggest the tens of thousands present that day (below). The mill and the surrounding slum are convincing, and Leigh has managed to find some unspoiled landscapes to provide a relief from the grimness of working-class life in the era. Amazon will release it in the US on November 9, as part of the film’s slightly premature celebration of the 200th anniversary of the event.

Check out our Instagram page for ongoing photos from the festival.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome of us to this year’s Biennale.

October 31, 2018: Netflix has announced that it will give Roma a theatrical release, starting on November 21 in New York and Los Angeles; it will be in more theaters starting December 7 and open wider on December 14. It will been seen theatrically in 20 countries. There will be several theaters showing it in 70mm.

Peterloo (2018)

Posted in Directors: Cuarón, Festivals: Venice, Film comments, National cinemas: Germany, National cinemas: Mexico, National cinemas: UK |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018: Big films on the big screen open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice 2018: Big films on the big screen

|