Monday | September 4, 2023

Patricia Highsmith (from Loving Highsmith, 2022).

DB here:

Crime fiction, whether in words or pictures, is a bigger category than we might initially think. There are whodunits, hardboiled detective stories, police procedurals, suspense thrillers, and stories of gangsters, professional crooks, and petty scoundrels (e.g., Elmore Leonard’s world). That’s a lot in itself. But since every plot of any interest depends on some disruption of a stable situation, an illegal transgression can do the trick. So we can get bank robbery in a comedy (e.g., Take the Money and Run, 1969), or murder and extortion in a family melodrama (The Little Foxes, play 1939, film 1941), or authorial disputes about plagiarism (Secret Window, 2004). Even romantic comedy has room for a crime or two (Date Night, 2010).

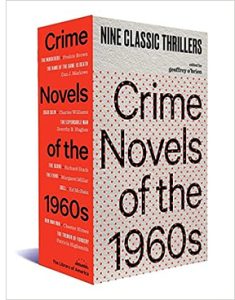

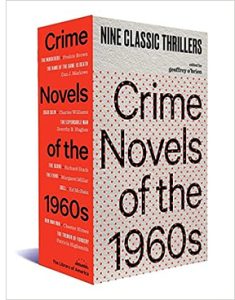

Geoffrey O’Brien is a polymath. He’s written poetry, evocative memoirs (Sonata for Jukebox, 2004), experimental fiction (the recent lyrical “fantasia,” Arabian Nights of 1934), and outstanding literary and film criticism (Castaways of the Image Planet, 2002). He’s also an expert in crime fiction (Hardboiled America, 1997), so he’s ideal for editing the new Library of America collection Crime Novels of the 1960s. His choices, all unimpeachable, cover a lot of the central creative options. There are crook stories, suspense thrillers, a police procedural, several strains of whodunit, psychological studies, and at least one crime novel possibly lacking a crime. In style they vary between pitiless hardboiled narration and more delicate but still forceful dissection of middle-class mores. As you might expect from books of their era, racial prejudice, urban upheavals, and the folkways of the counterculture are seldom far away. Geoffrey O’Brien is a polymath. He’s written poetry, evocative memoirs (Sonata for Jukebox, 2004), experimental fiction (the recent lyrical “fantasia,” Arabian Nights of 1934), and outstanding literary and film criticism (Castaways of the Image Planet, 2002). He’s also an expert in crime fiction (Hardboiled America, 1997), so he’s ideal for editing the new Library of America collection Crime Novels of the 1960s. His choices, all unimpeachable, cover a lot of the central creative options. There are crook stories, suspense thrillers, a police procedural, several strains of whodunit, psychological studies, and at least one crime novel possibly lacking a crime. In style they vary between pitiless hardboiled narration and more delicate but still forceful dissection of middle-class mores. As you might expect from books of their era, racial prejudice, urban upheavals, and the folkways of the counterculture are seldom far away.

Taking pulp mainstream

The nightmarish plots and staccato vernacular of O’Brien’s hardboiled sampling are vestiges of the pulp magazines, where Hammett and Chandler developed their technique in the 1920s and 1930s. But the classic crime pulps were long gone by the 1960s. What replaced them were the massive paperback originals pouring from presses from the Forties onward. A first paperback printing of a novel would routinely run to 150,000 copies. The success of cheap reprints of hardcover titles impelled publishers to capitalize on the new market with novels written specifically for paperback distribution. The most popular genre was crime fiction. Originals tended to be short, running 60,000 to 80,000 words, with plenty of blank space for laconic dialogues. A dedicated pro could turn out one in a month or two, at a fee of a few hundred dollars.

A vivid example in this collection is Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death, which first appeared as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback in 1962. It starts with three thieves executing a bank robbery. The opening plunges us into the crossfire of pulp narration. A vivid example in this collection is Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death, which first appeared as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback in 1962. It starts with three thieves executing a bank robbery. The opening plunges us into the crossfire of pulp narration.

Bunny went through the front door in a sliding skid. The kid took one look at my face and started to run back in front of the Olds. Across the street something went ker-blam!! The kid whinnied like a horse with the colic. He ran in a circle for three seconds and then fell down in front of the Olds, his white cottom gloves in the dirty street and his legs still on the sidewalk. The left side of his head was gone.

Bunny dropped the sack and scrambled for the wheel. I was halfway into the back seat when I heard the car stall out as he tried to give it gas too fast. It was quite a feeling. I backed out again and faced the bank, tried to have eyes in the back of my head for the unseen shotgunner across the street, and listened to Bunny mash down on the starter. The motor caught, finally. I breathed again, but a fat guard galloped out the bank’s front doors, his gun hand high over his head.

I swear both his feet were off the ground when he fired at me.

Bunny flees with most of the loot, and our nameless narrator escapes alone. He waits for news that Bunny has found sanctuary and is ready to divide the take. When the narrator hears nothing, he worries that Bunny is in trouble and sets out to find him. In his travels from Phoenix to Florida he encounters several problems that demand violent solutions. Across his trip, it becomes evident that our protagonist is a borderline sociopath.

His journey gives Marlowe’s plot a linear trajectory that is studded with flashbacks to his childhood, including a traumatic incident with his beloved cat. The episodes build a degree of understanding of his damaged personality, only to have that mitigated by a savage climax. Hardboiled to the end.

Donald E. Westlake, a favorite of this blog, was endlessly prolific, cranking out erotica, science fiction, comic fiction, psychological thrillers, and hard-core crime stories under several pseudonyms. He created two long-running series, both based on heist plots. A comic one centered on John Dortmunder, a hapless down-at-heel thief. The other series was dead serious (though with some light touches) focused on Parker, an impassive, nearly amoral robber specializing in organizing big capers. The Score (1964) is one of Parker’s most ambitious projects. With a large team, he ransacks an entire town. Donald E. Westlake, a favorite of this blog, was endlessly prolific, cranking out erotica, science fiction, comic fiction, psychological thrillers, and hard-core crime stories under several pseudonyms. He created two long-running series, both based on heist plots. A comic one centered on John Dortmunder, a hapless down-at-heel thief. The other series was dead serious (though with some light touches) focused on Parker, an impassive, nearly amoral robber specializing in organizing big capers. The Score (1964) is one of Parker’s most ambitious projects. With a large team, he ransacks an entire town.

Westlake broke nearly all his Parker novels into four parts, and within them he enjoyed mixing flashbacks and shifting viewpoints. Part 3 of The Score is a virtuoso panorama of the entire raid, played out in short scenes in different parts of town. It provides a careful layout of how the takeover is engineered. Most scenes are devoted to the robber in charge and provide us characterization that enlivens the action. As usual, the perfect heist goes badly wrong, and Westlake’s anatomy of the scheme forces us to admire its precision up until the final catastrophe.

Westlake exemplifies how the hardboiled tradition could be exciting without being sensationalistic. Avoiding the near-hysteria of Marlowe (no double exclamation points here) and the florid metaphors of Chandler, Westlake is close to Hammett in his understated but elegant style. He playfully references books and movies, as when Parker’s colleague Grofield imagines his thieving days as a long film with a musical score and swooping camera angles. I devoted a chapter of Perplexing Plots to the rigorous intricacy and captivating style of the Parker books. (For online instances, go here and here.)

Hitchcock and Evan Hunter (Ed McBain), who wrote the screenplay for The Birds.

The Score was a paperback original for Pocket Books, which also initiated Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series. McBain’s police procedurals mixed a realistic treatment of procedures (printed-out lab reports, fingerprint files, and the like) with a slangy dialogue redolent of the hardboiled pulps. Doll (1965) includes not only a gory murder but a series of punishing scenes in which a killer repeatedly injects a captive cop with heroin.

McBain sought to capture the protocols of investigation through the “conglomerate hero” formed by an entire squad. Although Steve Carella is the first among equals, inquiries get split up among his colleagues. In Doll Carella is reluctantly partnered with the troubled Bert Kling. But Carella soon disappears and is believed dead. Kling continues solo until he’s replaced by Meyer Meyer, who’s aided by colleagues Hal Willis and Arthur Brown. Eventually Kling rejoins the hunt and partners with Meyer to resolve the case. In other books, cases run in parallel or are revealed as connected. This sort of plotting, popularized in Hill Street Blues, is common in modern procedurals. McBain complained that others swiped his idea.

Another McBain innovation was an intrusive authorial voice. The action is typically recounted in the third person and through shifting viewpoints in a moving-spotlight manner, but the narration injects digressions and ventures into sheer chattiness. The opening of Doll interrupts the scene of a grisly murder with a lengthy reflection on how police cope with unimaginable crime scenes. This meditation isn’t attributed to Carella or anyone else. McBain, who was an English major in college, deliberately flouted the demand for neutral narration.

I know that in these books I frequently commit the unpardonable sin of author intrusion. Somebody will suddenly start talking or thinking or commenting and it won’t be any of the cops or crooks, it’ll just be this faceless, anonymous “someone” sticking his nose into the proceedings. Sorry. That’s me. Or rather, it’s Ed McBain.

McBain’s string of police procedurals quickly graduated to hardcover publication by Delacorte Press. His success exemplifies the new respectability of the pulp tradition.

The insanely prolific Fredric Brown gets some respectful mentions in Perplexing Plots for eccentric experiments like The Far Cry (1951). Echoes of the hardboiled school show up more mutedly in his The Murderers (1961). The protagonist, a shiftless would-be actor, drifts through Hollywood trying to pick up commercial gigs or small parts in an ongoing TV series. Mostly he’s interested in drinking and hanging out with hippies and pliable women. He gets attached to a businessman’s wife, and together they fumble into a murder scheme. There’s more than a passing resemblance to Double Indemnity, and the hero is a softer, semi-comic descendant of James M. Cain’s doomed fools for passion. Overall, Brown presents a cooler, more laid-back vision of Cain’s sunbaked California car culture and killing fields. As a bonus, Brown merges his murder scheme with another swiped ingeniously from the most prominent woman writer of psychological thrillers.

Murder with gravity

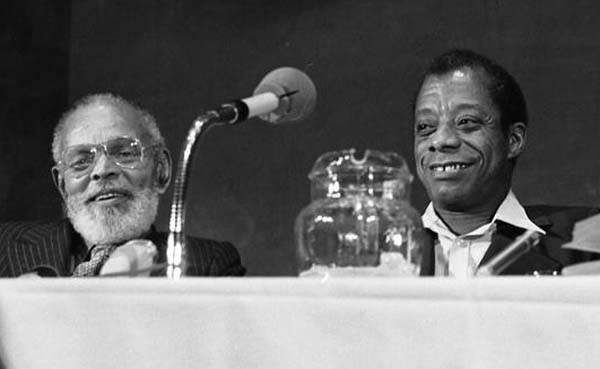

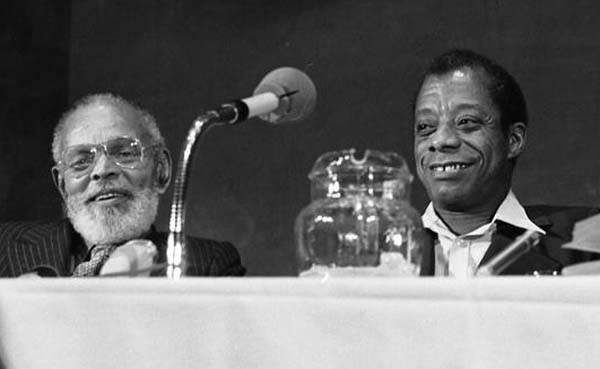

Chester Himes and James Baldwin, 1973. From Stars and Stripes.

Late one night a drunken, psychopathic cop shoots and kills a restaurant’s two kitchen cleaners. A third man witnesses the crimes and escapes. The cop uses all the authority of the law to pursue him. Moving-spotlight narration switches us rapidly from one man to the other as the tension builds and the cop closes in.

Sounds like pure pulp, no?

What if the cop is a racist, and his two victims and third target are Black?

That’s the premise of Chester Himes’ Run Man Run (1966). Himes was one of several Black artists and writers who found sanctuary in Paris after confronting postwar bigotry at home. He won fame in France, and belatedly in the U.S., with a series of hardboiled detective novels (some as paperback originals) centering on Gravedigger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. The best-known is Cotton Comes to Harlem (1966), which also became a lively movie.

His marquee cops are absent from Run Man Run, but the book is filled out by evocative descriptions of the Harlem milieu and sharp portrayals of the secondary characters, particularly the pursued man’s morally equivocal girlfriend and a cop who’s not as racist as his peers. The density of detail and the psychological probing of hunter and hunted give the book the gravity of a “serious” novel like Himes’ excellent If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945).

Gravity of a comparable sort dominates Charles Williams’ Dead Calm (1963). The situation merges two long-lasting schemas: the woman menaced by the sociopathic killer, and the man trapped aboard a sinking ship. A couple honeymooning in a yacht come to the aid of an apparent castaway and get far more than they expected. Williams gives unremitting apprehension by crosscutting the two situations while also filling in the backstory in ways that add layers of understanding and misunderstanding. It’s a model blend of mystery and suspense.

It’s also a lesson in another, frequently forgotten side of the hardboiled tradition. The tough guy isn’t just a mindless thug; he’s often the master of a delicate craft. Stark’s Parker is a virtuoso in breaking and entering, but also in calmly managing the problems that come up. He works with his hands but also his mind. So does the central male of Dead Calm. John Ingram must draw on his expertise in professional sailing to stay alive in a crisis, and Williams freely lets us understand the minutiae of survival to make us admire his resourcefulness. More significant, Ingram’s wife has absorbed many of the same skills, and her shrewd use of them renders her as no less tough an adversary.

Williams’ rich vocabulary yields the pleasure of watching neat, efficient intelligence in a crisis. Another sort of literary gravity, then, makes this book as evocative as any piece of straight fiction, and more gripping than most. No wonder that Philip Noyce and Terry Hayes were able to adapt it to the screen in 1989 with trim economy.

Ladies of crime

Women writers have been prominent in crime fiction virtually from the start. Anna Katherine Green’s bestselling detective story The Leavenworth Case (1878) predates Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series. Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Marjorie Allingham and others became famous for their mystery novels. In the 1930s and 1940s, Charlotte Armstrong, Elizabeth Sanxay Holding, Vera Caspary, and many others contributed both whodunits and psychological thrillers. Sarah Weinman has collected some of these authors’ outstanding suspense novels in a fine Library of America set, which I discuss in another entry.

Among these admirable artisans was Dorothy B. Hughes, whose Ride the Pink Horse (1946) and In a Lonely Place (1947) were adapted to films that became prime examples of what was later called film noir. Hughes also wrote a discerning critical biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. She reflected thoughtfully on the conventions of crime fiction, reviewing books and even teaching a course at UCLA in the 1960s. Among these admirable artisans was Dorothy B. Hughes, whose Ride the Pink Horse (1946) and In a Lonely Place (1947) were adapted to films that became prime examples of what was later called film noir. Hughes also wrote a discerning critical biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. She reflected thoughtfully on the conventions of crime fiction, reviewing books and even teaching a course at UCLA in the 1960s.

Perhaps her acute awareness of how thrillers manipulate viewpoint to maximize anxiety and to build up mystery led her to The Expendable Man (1963). It’s a wrong-man plot. Out of a spurt of kindness Dr. Hugh Densmore picks up a hitchhiking teenage girl on a lonely desert highway. She turns out to be reckless, manipulative, and obviously dangerous. Densmore lets her out at several points on the way, only to find her waiting for him further along. In Phoenix, where he’s come for his niece’s wedding, the young doctor learns that the girl has been murdered. He’s a prime suspect.

During his first police interrogation, Hughes casually drops in a shock that makes the reader reevaluate everything that’s led up to it–and feel not a little shame in the bargain. After this tour de force, Densmore’s struggle to prove himself innocent takes on a new pressure that adds enormously to the growing tension. Sorry to be so cryptic, but you have to read it in innocence to feel the diabolical force of Hughes’s scheme.

Margaret Millar, Santa Barbara. From “Margaret Millar Rediscovered,” Bay Area Reporter.

The Expendable Man locks us tightly to Densmore’s consciousness, while another book by a queen of suspense uses a wider-ranging narration. In Margaret Millar’s The Fiend (1964), a moving-spotlight narration reveals sharp criticism of how wives chafe under suburban routine.

Charlie Gowen spends his lunch hour sitting in his green coupé watching children in a playground. He becomes worried that one little girl takes risks on the jungle gym, and he fears that her parents are neglecting her. This concern grows to the point that he sends an anonymous letter to her mother. But he sends it to the wrong family. From this festers a plot of intricate lies, revelations, misunderstandings, and accusations that pulls in an entire neighborhood–friends, other kids, librarians, a lawyer, a pharmacist, Charlie’s caretaker brother, a would-be romantic partner, and of course the police.

Millar was a major crime novelist recognized in her day but now little-known. (Her fame was eventually surpassed by that of her husband Kenneth Millar, aka Ross Macdonald. I think she’s the better writer.) Her many first-rate suspense novels include A Demon in My View (1955) and Do Evil in Return (1950), a sensitive probing of a female doctor deciding whether to perform an illegal abortion. The Fiend sustains suspense to the very last page while offering portraits of children’s efforts to understand adult hypocrisy, and the various ways women cope with suffocating domesticity–not least, the obliteration of their identities. All this is given in a rich evocation of the milieu, down to the redwood picnic tables at a backyard barbecue and chipmunks scampering up lemon trees.

Unlike Millar, Patricia Highsmith was often underrated by American genre fans, while highbrow critics mostly ignored her. Fame has come to her more recently, thanks largely to popular film adaptations of her books (especially The Talented Mr. Ripley, 1999) and her tumultuous life as a Lesbian. Her personality, alternately fascinating and repelling, has too often distracted commentators from the power of her plotting and style. I try in Perplexing Plots to provide an analysis of some of her major storytelling strategies.

Her other books do not fully prepare you for The Tremor of Forgery (1969). It’s a crime novel in which the crime has the haziness of a mirage. Howard Ingham is in Tunisia starting to prepare a screenplay when his progress halts after the death of his producer in New York. He decides to linger and work on his next novel. That centers on an amoral, Ripleyesque bank executive stealing funds from accounts. In the real world, Ingham loiters, tours Tunisia, and strikes up friendships with a gay neighbor and a peculiar American propagandist. He also broods on whether his producer was having an affair with Ina, a woman he might marry. All this takes place against the background of the six-day Arab-Israeli war and the ongoing war in Vietnam.

Eighty pages in, Ingham takes a hasty action that may have resulted in a man’s death. By utterly limiting the viewpoint to Ingham, Highsmith keeps us in uncertainty about the consequences. The rest of the book plumbs Ingham’s mind as he tries to discover what he may have done and reacts to the responses of those around him. Highsmith’s finesse in keeping us in suspense about the exact contours of the incident releases her from what Henry James called “weak specification.” Instead she puts at the center of our attention Ingham’s fluctuating uncertainties about what he has done and should do.

The title refers to the telltale tremor in the sort of forgeries that Ingham’s embezzler Dennison commits. If it’s a symptom of guilt, it’s also a trace of Highsmith’s perennial theme of the instability of a person’s identity. Sometimes Ingham feels that he’s no more than all the opinions about him others hold. The Tremor of Forgery asks to what extent all our momentary roles are forgeries, and whether our moments of guilt and indecision betray a fundamental emptiness. At one moment, Ingham considers the possibility that “One was nothing anywhere, ever.”

As usual for the Library of America, these nine powerhouses are presented in elegant editions, filled out with plenty of authorial background and bibliographical sources. Just as important, this publishing initiative does a lot to dissolve that boundary between art and entertainment I objected to in an earlier entry.

Dead Calm (1989).

Posted in Film and other media, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book) |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Crime spree open printable version

| Comments Off on Crime spree

Friday | August 25, 2023

DB here:

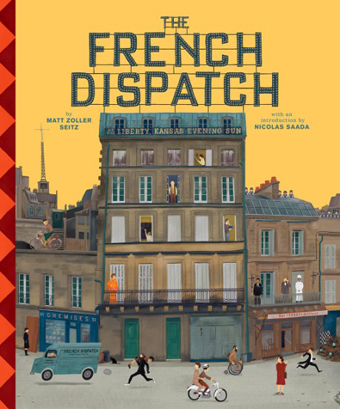

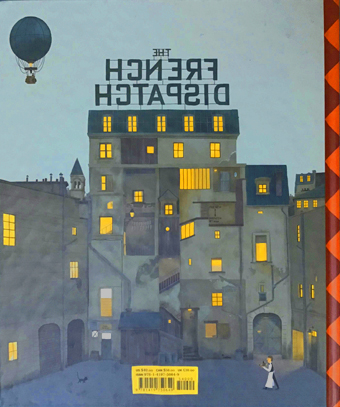

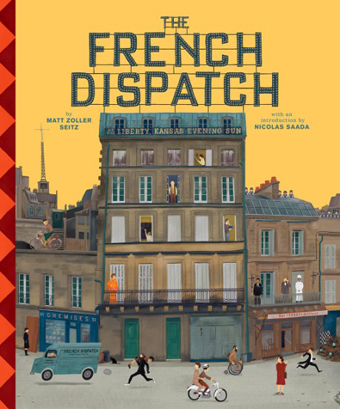

Hardcore Wes Anderson admirers will be happy to learn of the latest entry in the series of massive auteur monographs devoted to the work of the director. After a synoptic volume, The Wes Anderson Collection, there followed one devoted to The Grand Budapest Hotel and another to Isle of Dogs. Now we have one on The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun. Delayed a bit by Covid, it emerges as just as splendid as its predecessors.ƒteem

Matt Zoller Seitz, impresario of the series, has compiled all the materials we’ve come to expect. There are the usual frolicsome illustrations by Max Dalton. We get to roam through production documents, sketches, storyboards, and interviews with participants, including extras and peripheral contributors. Anderson’s appetite for material is endless, so we learn of layers of citations, shout-outs, and subterranean influences. Binding it all is Seitz’s commentary, both a narrative of the project’s development and an ongoing conversation with Anderson himself.

Seitz is not only a dynamic critic but an imaginative book-maker, with daring conceptions of design and illustration. His gifts are apparent not only in this series but in his nearly phantasmagoric compendium on Oliver Stone and in his more austere but no less forceful The Deadwood Bible. The Anderson enterprise began as a website, and each book has the centrifugal energy of a nest of hyperlinks, with new bits piling onto a single page.

Seitzian ingenuity also emerges in clever ways to evoke, if only as riffs, the obsessive, occasionally silly whimsy that drives the director and his characters. The first book in the series provided a word count for each chapter; the Grand Budapest Hotel volume assigns contributors the role of concierges (“The Society of the Crossed Pens”). In the spirit of a movie about a magazine, The French Dispatch entry includes a magazine, Fondu enchaîné (“Dissolve”). In this English-language feast of cinephilia several critics provide close considerations of the film. (Full disclosure: I’m one of those critics.) The expansive range of these essays nicely miniaturizes the whole book’s urge to explore anything, no matter how remote, that can illuminate the film and Anderson’s creative process.

In all, it’s a collection that I think will delight any Anderson admirer. It teems with the same energy that has animated his body of work for twenty-five years and counting. How fast that time has gone!

Thanks to Ben Adler for all his help on this and other projects.

Full disclosure #2: Matt has kindly co-dedicated the book to Kristin and me. We accept it with gratitude from a generous friend.

Posted in Books, Directors: Anderson, Wes |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Another dispatch from Ennui-sur-Blasé open printable version

| Comments Off on Another dispatch from Ennui-sur-Blasé

Sunday | July 23, 2023

The Maltese Falcon (1941).

DB here:

The traditional opposition between Art and Entertainment still holds some sway. Art, some believe, is the realm of higher significance and profound emotion, while entertainment yields mere diversion and superficial engagement. Art embodies wisdom and technical breakthroughs, while at best entertainment is home to talent and cleverness. Art harbors genius, entertainment offers ingenuity. Art expresses the creator’s personal vision, entertainment recycles collective fantasy (or the Zeitgeist). There’s usually an implied hierarchy of quality and of appeal: art is for a sensitive elite, entertainment is popular (read vulgar).

One problem, though, is that for long stretches of history much art has been thoroughly entertaining. Mozart, Shakespeare, Dickens, Hiroshige, Austen, and many other major artists have found wide popularity. They provide pleasure aplenty. But with urbanization and the rise of capitalism, mass production created a huge public, and tastemakers have tended to treat art as a realm apart. For a hundred years or more, entertainment has been equated with mass culture, and art with high culture, most notably with modernism and its successors.

Another problem is cultural endurance. In a recent column, Michael Dirda points out that genre fiction often outlasts prestigious literary fiction of its era.

Take fantasy and science fiction: In 1997, I praised William Gibson’s “Neuromancer,” John Crowley’s “Little, Big,” Gene Wolfe’s “Book of the New Sun” and the works of Ursula K. Le Guin — all remain vital to contemporary writers and readers.

Similarly, classics of mystery fiction by Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Patricia Highsmith still attract readers, while “mainstream” novels of their eras are forgotten. Dirda’s second point is no less valid.

More generally, American novelists have wholly embraced the energy and potential of fantasy in its various forms. We are all fabulists now. This century revels in comics, graphic novels, manga and superhero movies. Authors as varied as Colson Whitehead, Walter Mosley, Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, Elizabeth Hand and Michael Chabon, to name a few prominent figures, all grew up loving fantasy and science fiction.

Genre appeals have infiltrated prestige literature, as in the crime plots of Graham Greene, Joyce Carol Oates, and Richard Price. (I consider Colson Whitehead’s and Richard Wright’s contributions here.) Likewise, we have horror-infused tales like George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo and Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home .

Creators of entertainment have felt the distinction keenly. “A wedge has been driven into the industry,” says Christopher MacQuarrie, director of the latest Mission: Impossible installment. “Are you an artist or an entertainer? Tom doesn’t see them as mutually exclusive.” But some creators have seen a forking path. Rex Stout, after several “serious” novels failed, came to two conclusions:

First—that I was a good storyteller, and second—that I would never be a great novelist. I’d never be a Tolstoy, or a Dickens, or a Balzac…. So since that wasn’t going to happen, to hell with sweating out another twenty novels when I’d have a lot of fun telling stories which I could do well and make some money on it.

The Art/ Entertainment distinction runs through my recent book, Perplexing Plots, because many mystery writers have aimed at “elevating” their work to the level of prestige literature. This urge drives them to experiment with the norms of plotting and writing. Even when the genre limits remain in force, there’s a chance that skillful exponents can accept them and still yield “literary” pleasures. A good example is what happened to hard-boiled detective fiction in the hands of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

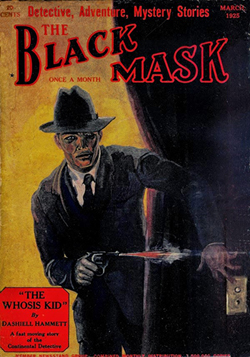

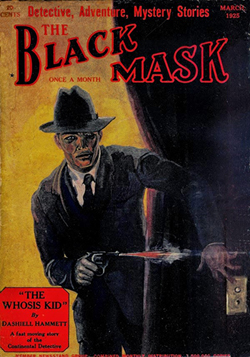

The Op

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique. Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Black Mask stories put a premium on action, so the Op was often at the center of violence perpetrated by crooks, sociopaths, and corrupt cops. Unlike other hard-boiled detectives, the Op isn’t a swaggering sadist. Violence is his last resort; he favors obstinate everyday professionalism. Sometimes he’s fooled by the grifters and has to wriggle his way out. At other times, he can set crooks against one another and watch the mutual destruction.

Hammett wrote the stories in the first person, giving the Op a telegraphic, visceral style laced with sour humor. A 1923 story shows his American vernacular already in place.

Just at the wrong minute Henderson decided to look over his shoulder at us–an unevenness in the road twisted his wheels–his machine swayed–skidded–went over on its side. Almost immediately, from the heart of the tangle, came a flash and a bullet moaned past my ear. Another. And then, while I was still hunting for something to shoot at in the pile of junk we were drawing down upon, McClump’s ancient and battered revolver roared in my other ear.

Henderson was dead when we got to him–McClump’s bullet had taken him over one eye.

McClump spoke to me over the body.

“I ain’t an inquisitive sort of fellow, but I hope you don’t mind telling me why I shot this lad.” (“Arson Plus”)

In 1929, the publisher Knopf issued two Hammett novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, based on Black Mask serials. The Op had not lost his wit or his gift for staccato narration. Here are three excerpts.

I didn’t think he was funny, though he may have been.

He stood at the foot of the bed and looked at me with solemn eyes. I sat on the bed and looked at him with whatever kind of eyes I had at the time. We did this for nearly three minutes.

The latch clicked. I plunged in with the door.

Across the street a dozen guns emptied themselves. Glass shot from door and windows tinkled around us.

Somebody tripped me. Fear gave me three brains and half a dozen eyes. I was in a tough spot. Noonan had slipped me a pretty dose. These birds couldn’t help thinking I was playing his game.

I tumbled down, twisting around to face the door. My gun was in my hand by the time I hit the floor.

Across the street, burly Nick had stepped out of a doorway to pump slugs at us with both hands. I steadied my gun-arm on the floor. Nick’s body showed over the front sight. I squeezed the gun. Nick stopped shooting. He crossed his guns on his chest and went down in a pile on the sidewalk.

Hands on my ankles dragged me back. The floor scraped pieces off my chin. The door slammed shut. Some comedian said:

“Uh-huh, people don’t like you.”

As he was finishing The Dain Curse, Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf confessing that in future work he wanted to go beyond Entertainment to Art.

I’m one of the few—if there are any more—people moderately literate who take the detective story seriously. I don’t mean that I necessarily take my own or anybody else’s seriously—but the detective story as a form. Some day somebody’s going to make “literature” of it (Ford’s Good Soldier wouldn’t have needed much altering to have been a detective story), and I’m selfish enough to have my hopes, however slight the evident justification may be.

The question is: How to do this?

Inside and outside

Hammett proposed an answer in his letter to Blanche Knopf. He wanted to try that he wanted to try out modernist technique in a third novel.

I want to try adapting the stream-of-consciousness method, conveniently modified, to the detective story, carrying the reader along with the detective, showing him everything as it is found, giving him the detective’s conclusions as they are reached, letting the solution break on both of them together. I don’t know whether I’ve made that very clear, but it’s something altogether different from the method employed in “Poisonville [Red Harvest],” for instance, where, though the reader goes along with the detective, he seldom sees deeper into the detective’s mind than dialogue and action let him.

His mention of stream of consciousness may mislead us about his intentions. In that technique the verbal narration seeks to mimic the flow of the mind as it flits across sensory impressions, memories, and fantasies. The process is often rendered as sentence fragments, often introduced by a sentence indicating the behavior of the character.

Here’s an example from Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the most famous showcase of stream of consciousness. Mr. Bloom is in a Catholic church.

He saw the priest stow the communion cup away, well in, and kneel an instant before it, showing a large grey bootsole from under the lace affair he had on. Suppose he lost the pin of his. He wouldn’t know what to do to. Bald spot behind. Letters on his back I.N.R.I? No: I.H.S. Molly told me one time I asked her. I have sinned: or no: I have suffered, it is. And the other one? Iron nails ran in.

Sometimes the images and phrases are separated by commas and periods, but sometimes they simply pile up. In the book’s last chapter, Molly Bloom’s drowsy imaginings are given in an unpunctuated, sparsely paragraphed flow.

It’s likely that Hammett didn’t want his usage to be as fragmentary as what we encounter in Joyce and others. His invocation of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915) suggests something closer to what many now call inner monologue. (Ford called it “impressionism.”) Here the flow of thought is given as a sort of soliloquy, a flow of more or less cogent and coherent ideas and impressions. What makes it a modernist technique is that inner monologue may not respect story chronology and it’s likely to be biased, uncertain, equivocal, and subject to revision. Ford’s narrator, John Dowell, tells a rambling, out-of-order tale of marital infidelity and suicide, in which flashbacks are analyzed and re-analyzed.

Looking over what I have written, I see that I have unintentionally misled you when I said that Florence was never out of my sight. Yet that was the impression that I really had until just now. When I come to think of it she was out of my sight most of the time.

At the climax, Dowell makes a provisional sense of what the characters knew and why they acted as they did.

The problem in importing this to the detective story is evident. How can the detective’s ongoing reasoning, bristling with mistaken inferences and reconstructed impressions, be passed along to the reader without causing confusion? For this reason, detective story narration, whether first-person or third-person, suppresses most of the protagonist’s reasoning. The Watson figure and the dumb authorities exist to be baffled and play with misleading possibilities while the detective holds back even a partial solution.

By convention, the climax of the tale is the revelation of the truth–not when the detective discerns it, but at the moment when it can be announced with decisive impact (often in a gathering of suspects with the police present). Raymond Chandler noted that the delayed revelation was a serious constraint of the genre, even when the detective, like the Op, is telling the story. “The first person story is assumed to tell all but it doesn’t. There is always a point at which the hero stops taking the reader into his confidence.” The detective “stops thinking out loud and ever so gently closes the door of his mind in the reader’s face.” This prevents the public announcement of the solution from being anticlimactic.

Worse, Ford’s protagonist Dowell is an unreliable narrator, as the above passage suggests. To make the detective’s first-person account unreliable would be more than a “convenient modification” of the standard plot schema. It would push toward the experiments seen in Cameron McCabe’s The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) and later “anti-mysteries.”

Hammett admitted in a later letter that he would put the “stream-of-consciousness” experiment on hold while he wrote material for Hollywood in “more objective and filmable forms.” (That would include his script for City Streets of 1931, which does include a subjective auditory flashback rare in films of the time.) But in his next novels Hammett turned sharply away from the interiority he had considered. Instead, he went toward extreme objectivity, almost completely shutting us out from his protagonists’ inner lives.

The action of The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1930) attach us closely to his protagonist, scene by scene. We’re confined to his activity and his range of knowledge. But this doesn’t get us into his mind. For these books Hammett switched to third-person narration and made it radically objective, sticking almost completely to reporting dialogue and character interaction.

In Perplexing Plots, I explore how this strategy works, but here’s an example from The Glass Key.

At Madison Avenue a green taxicab, turning against the light, ran full tilt into Ned Beaumont’s maroon one, driving it over against a car that was parked by the curb, hurling him into a corner in a shower of broken glass.

He pulled himself upright and climbed out into the gathering crowd. He was not hurt, he said. He answered a policeman’s question. He found the hat that did not quite fit him and put it on his head. He had his bags transferred to another taxicab, gave the hotel’s name to the second driver, and huddled back in a corner, white-faced and shivering, while the ride lasted.

The narration presents what a third-person observer would have seen and heard, and it won’t venture into Beaumont’s thinking. The cues are behavioral: he seems cool enough in slipping out of the crash, but his true reaction is given through his nervous reaction while riding back to the hotel.

As Hammett’s second letter to Blanche Knopf suggests, this flat objectivity would seem an ideal novelistic basis for a “filmable” treatment. John Huston’s screen adaptation of The Maltese Falcon confines us almost completely to Spade’s range of knowledge. (The big exception is that we see his partner Miles Archer shot by an unknown killer.) The film’s visual narration mostly follows Hammett’s impassive neutrality. But when Casper Gutman drugs Spade, we get Spade’s clouded optical viewpoint.

In the novel the narration reports that Spade’s eyes seemed to muddy over. When he says, “And the maximum?” we’re told that “An unmistakable sh followed the x in maximum as he said it.” This isn’t Spade’s experience but rather what an observer would register, an “unmistakable” impression confirmed when we’re told that “a sharp frightened gleam awoke in his eyes.” As Spade tries to walk, he’s tripped by Wilmer. He falls and Wilmer kicks him. “Once more he tried to get up, could not, and went to sleep.” The whole scene is rendered externally.

So instead of giving the detective story a modernist subjectivity, Hammett went to the other extreme. Did he intuitively recognize the problem of revealing the detective’s inferences too soon? Maybe, although his increasing involvement with Hollywood may have kept him on the objective, “filmable” path. The Thin Man (1934), his last novel, is a fascinating effort to return to first-person narration while incorporating the dry objectivity of the two previous books.

Perhaps inadvertently, Hammett’s radicalization of the objective method yielded what he had hoped for. The Maltese Falcon was greeted as a serious work of literature and was soon incorporated into the prestigious Modern Library series. His works have become part of the canon of American letters enshrined in the Library of America collection. The convention of delaying the detective’s solution didn’t prevent the genre from becoming accepted as a legitimate literary form–at least as practiced by Hammett, and his most prominent successor.

Overtones, echoes, images

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.” That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

But what Chandler means by “understanding” doesn’t include full-blown reasoning. First-person narration, he explains in a 1949 note, must “suppress the detective’s ratiocination while giving a clear account of his words and acts and many of his emotional reactions.” This seems a response to the detached reportage of late Hammett prose. Chandler also rejects the Op’s streetwise patter by explaining to Knopf that his method will use “a very vivid and pungent style, but not slangy or overtly vernacular.” He wants “to acquire delicacy without losing power.”

Hammett, while a voracious reader, learned a good deal of his craft from actually investigating crimes. Chandler, who began writing mysteries as Hammett’s productivity tailed off, owed his knowledge of the mystery genre to reading. He studied crime fiction of all sorts with almost academic passion and became one of the most nuanced commentators on the tradition. He claimed to have learned plotting from outlining pulp stories by Erle Stanley Gardner. His literary tastes didn’t run to modernism. He admired the Greek and Roman classics, Flaubert, James, and Conrad and thought highly of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Hammett imagined elevating the genre by “conveniently modifying” modernist technique, but Chandler sought to make the hard-boiled detective story more like the ambitious mainstream novel.

He believed he could do that through style. In his crucial essay, “The Simple Art of Murder (1944/1946),” he praises Hammett’s prose but objects that “it had no overtones, left no echo, evoked no image beyond a distant hill.” Chandler sought to give style a greater novelistic richness not only through probing his protagonist’s mind but also through fairly dense descriptions colored by the protagonist’s emotions and judgments.

Hammett sketches characters in quick strokes and he merely indicates settings. But Chandler dwells on his characters and their surroundings. The opening of The Big Sleep devotes a page and a half to Philip Marlowe’s impressions of the Sternwood mansion (stained-glass window of a knight rescuing a lady, plush chairs, a mysterious portrait) and another page and a half to his meeting with the coy Carmen. These are filtered through Marlowe’s running commentary. The knight doesn’t really seem to be trying. The chairs appear to never have been sat in. The portrait looks threatening. Carmen’s infantile flirtation reveals that “thinking was always going to be a bother to her.” Here are the overtones and echoes that Chandler finds lacking in Hammett. This is an ominous household–as Marlowe will later say, this will be “no game for knights.”

Chandler would pursue this method in the following novels. Yet at times the narration plunged deeper into subjectivity. In Farewell, My Lovely (1940) Marlowe is repeatedly knocked out in tussles, and in the second passage Chandler writes:

The man in the back seat made a sudden flashing movement that I sensed rather than saw. A pool of darkness opened at my feet and was far, far deeper than the blackest night.

I dived into it. It had no bottom.

The film adaptation, titled Murder, My Sweet (1944), uses this subjective device in every knockdown. Marlowe’s voice-over narration runs through the film, and after the first assault we hear:

I caught the blackjack right behind my ear. A black pool opened up at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom.

Onscreen we see Marlowe’s crumpled body blotted out by a miasma that leads to a black frame.

In a later sequence, a knockout of Marlowe is rendered as wild optical exaggerations before following the novel’s report of Marlowe seeing a room full of smoke. That’s translated as wispy superimpositions over the shots, with explanatory voice-over.

The film tries a bit too hard, but its use of voice-over and delirious visual subjectivity would become common in film noirs of the period.

In Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe’s recovery from his first knockout is rendered with vigorous subjectivity across two pages, as Marlowe realizes that the voice he hears reviewing what happened is his own. “I was talking to myself, coming out of it. I was trying to figure the thing out subconsciously.”

Marlowe is able to reconstruct bits of the crime through this process, but it’s a provisional solution, not the decisive one. That one he keeps from the reader until the climax. By then, as per convention, the door to his mind has shut in the reader’s face.

Hammett’s novels were published when most crime fiction consisted of genteel whodunits and gangster sagas, so he had the advantage of novelty. By the time Chandler published The Big Sleep, he was competing with many book-length stories of hard-boiled investigators. Aware of the need to establish a distinctive presence, he presented work that stood apart by its social criticism and the romanticized realism of a righteous avenger alone on the mean streets of a corrupt city–sure-fire attractions to intellectuals then and since. Just as important was his self-consciously literary style. “In the long run, however little you talk or even think about it, the most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the most valuable investment a writer can make with his time.”

Through concern with language’s echoes and overtones, he established himself as Hammett’s successor. The literati followed his lead and declared him a significant novelist. His books, along with “The Simple Art of Murder,” provided an enduring rationale for the tough detective story. While adhering to the conventions of the classic puzzle (clues, faked deaths, false identities, least-likely culprit), he acquired lasting prominence. Like Hammett he has found a home in the Library of America.

Arguably Hammett and Chandler also elevated their genre. Their achievements encouraged other ambitious writers and stimulated critics and readers to look more closely at the possibilities of the murder novel. No wonder that prestigious writers have turned to mystery plots. Fans still labor to make a case for Golden Age puzzles as art rather than entertainment, but most critics and readers assume the hard-boiled mystery to be at least potentially serious literature–especially when it goes under the alias “noir.”

Nowadays the Art/ Entertainment duality has weakened its hold. If, as Dirda suggests, we are all fabulists now, we’re also probably mystery fans to some degree. It’s likely that film played a role in dissolving the duality. Intellectuals began to understand that films by Ozu, Hitchcock, and other popular directors were of high quality. More and more, I think, people aren’t as eager to see the split as absolute. Instead of a hierarchy, we have more of a spectrum.

In harmony with this, Perplexing Plots argues that culture offers us a plenitude of individual works with varied appeals, all of which can be realized with, to use Chandler’s terms, delicacy and power. Some works rely on subtlety, others on immediate impact. We have the refinements of Baroque music and the direct force of The Rite of Spring. If Treasure Island is a masterpiece as well as a rousing yarn, so is Die Hard. There is heavy art and light art, brooding art and and diverting art, intellectual density and emotional charm. None of these qualities is simple or easy to achieve; all can repay analysis. The slogan might be: “There’s valuable work at all levels. And there are no levels.”

One source of value, not always acknowledged, is the role of entertainment in revealing fresh expressive possibilities in the medium. For example, the martial arts cinemas of Japan and Hong Kong opened up new vistas of cinema. And yes, as Hammett and Chandler indicated, a lot of the freshness lies in style. This is why Perplexing Plots spends time looking closely at how mystery fiction and film work, word by word or shot by shot. Even Agatha Christie’s supposedly bland verbal texture points up ways in which language can mislead us.

So Hammett and Chandler didn’t “elevate” the hard-boiled story so much as blur the line between genre fiction and the “legitimate” novel. Ambler and Le Carré did the same for the spy story, as did Highsmith for the psychological thriller. For such reasons, Perplexing Plots discusses hard-boiled detection extensively. I explore the Art/ Entertainment distinction because it has obsessed critics and creators. But I try not to buy into the split, opting instead for the looser idea of “crossover.” It’s a swap meet, with storytellers ransacking works “high” and “low” for subjects, forms, techniques, whatever.

I wanted to put up this entry on 23 July, Raymond Chandler’s birthday. It happens to be mine too. No cheerleading here, though. I prefer Hammett, as maybe you can tell.

My quotations from Hammett’s letters come from Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett, 1921-1960, ed. Richard Layman and Julie Rivett (2002). I take Chandler’s remarks on mystery fiction from Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank MacShane (1981) and Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardiner and Katherine Sorley Walker (1962).

Michael Dirda, as my mentions of him should lead you to expect, has written an admirable example of taking popular storytelling seriously but not solemnly: On Conan Doyle, or the Whole Art of Storytelling (2014). Kristin does something similar in her Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes, or Le Mot Juste (1992), available here and here. Her immensely popular subject, P. G. Wodehouse, was regarded as a master of English prose by Martin Amis, Evelyn Waugh, and many other literary celebrities.

What about the third celebrated hard-boiled pioneer, Ross Macdonald? Read Perplexing Plots to find out!

Murder My Sweet (1944).

P.S. 11 October 2023: In a Slate essay, Dan Sinykin shows that the merging of “genre fiction” and “literary fiction” has causes in the economics of the publishing industry. A fine analysis I wish I’d had available for Perplexing Plots.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Film and other media, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book) |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Art, entertainment, and the hard-boiled mystique open printable version

| Comments Off on Art, entertainment, and the hard-boiled mystique

Saturday | July 8, 2023

Wreck-It Ralph (2012).

Kristin here:

Way back in 2006, I posted a long piece on the increasing prominence of animated features being released each year. This was in the infancy of the blog, and the entry shows it–few photos, inserted as thumbnails. We only gradually worked up to our format of posting plenty of illustrations. By contrast this current contribution offers plenty of visual pleasure.

Basically I argued three points. First, that by their nature animated films would tend to be among the highest-quality films in any given year, despite their relatively small number in those days.

My argument laid out some reasons for this high quality. First, the fact that animated films were perforce thoroughly planned in pre-production, meaning that every detail was carefully considered. This means that relatively few inadequate scenes are reworked in production. Live-action films these days tend to be heavily dependent on shooting lots of coverage and making many decisions in the editing stage. Not true of animated films. Similarly, the soundtrack is recorded in advance and the images animated to sync with it. Hence the sound is meticulously planned. The voice actors record their voices and leave, usually not hanging around to try and change their scenes during shooting or fluffing lines and thus requiring multiple retakes of scenes.

My second point addressed the opinion, widely circulating in the trade press, that the spread of animation, and particularly digital animation, was a mistake. I quoted a recent Screen International article: “Much has been made this year of the seeming over-saturation of studios’ computer-generated titles, with critics and analysts pointing to growing movie-goer apathy.” I pointed out that such a claim didn’t fit the facts: “As a proportion among the total number of films made, CGI’s box-office successes seem fairly high compared to live-action films.”

My third point was that American distributors did not know how to market films from abroad, so that Ghibli and Aardman titles did not get nearly the audiences they deserved. Since then the distributor GKIDS has shown that it’s possible, at least for a relatively small company, successfully to release such films. They currently offer films with eleven best-animated feature Oscar nominations (with one win, Spirited Away), having gained distribution rights to Ghibli films, previously controlled by Disney.

Since I wrote that entry, the number of animated films, mostly digital, released yearly has sharply increased. And the disproportionate number of those animated films that appear among the top hits of the year continues to demonstrate that people are not apathetic. The spread of streaming services, combined with the decline of theatrical attendance during the pandemic, make it difficult to judge the success of films. Going back to 2019, where it’s a bit easier to judge, the top ten films included two animated successes, Toy Story 4 and Frozen II. An additional two were in the top twenty, How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World and The Secret Life of Pets 2. Animated films did not make up 20% of all films released, but that’s the portion of the top twenty they occupied.

I followed up that entry with one that found additional evidence that animated features were doing well, including the fact that Ice Age: The Meltdown was, though not the top box-office film of 2006, the most profitable film of that year.

So many developments have occurred in the world of feature animation since that first post that I decided to write an update.

The neighborhood is getting crowded

To some extent today’s update was inspired by a recent online post concerning new competition for Disney, which had absorbed Pixar and easily led the box-office race for years, with Dreamworks a second-run. Current developments led Alexandra Canal to point out some interesting figures. In 2022, Disney’s box-office total was $1.93 billion in ticket sales, for 26% of market share. Universal, number two, generated $1.64 million, for 22%, and Sony’s box-office coming in at a mere $834.8 million, or 11%. But things are changing. Other studios’ investments in building animation wings have started to challenge Disney’s dominance of the market for these films.

So far in 2023, as of July 1, Universal has The Super Mario Bros. (released April 5) at number one on the top-grossing list and over $1.3 billion worldwide. Sony has Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (June 2) at number four and approaching $620 million worldwide. By contrast, Disney has had two flops in recent memory: Lightyear (which I found mildly entertaining but not what I expect from Pixar) under-performed last summer, and Disney’s own Strange World (November 23) ended up with less than $74 million. Disney’s film in the top ten is the live-action version of The Little Mermaid (May 26), at number five with just over half a billion.

It will probably take several years for the long-term effects of streaming and the theatrical distribution recovery (if any) will have on Disney’s dominance. Still, it seems that the other Hollywood studios’ move toward creating their own animated departments is succeeding to some extent. The trend toward a greater variety of animated films may last.

Best Animated Feature or Best Picture? Which will win?

For this entry I have picked a rather arbitrary method of comparing quality animated films with quality live-action ones. I’m going to look at the Best Animated Films Oscar winners and nominees in comparison to the Best Picture ones.

Every now and then someone points out that such excellent animated films are now being turned out regularly that it would be logical to nominate the best of them for Oscars in the Best Picture category. There has never been a rule against such a crossover. So far it has only happened three times: Beauty and the Beast (1991, before the Best Animated Feature category existed), Up (2009), and Toy Story 3 (2010). None won, though they did take home Oscars in their own race. Other categories are technically open to animated films. Seven have been nominated for best screenplay, all Pixar films, with none winning.

A somewhat comparable situation has happened in the Foreign Language category. We tend to forget, but ten foreign-language films have been nominated for Best Picture: Grand Illusion (1938), Z (1969), The Emigrants (1972), Cries and Whispers (1973), Il Postino (1975), Life Is Beautiful (1998), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Babel and Letters from Iwo Jima (both 2006), Amour (2012), Roma (2018), Parasite (2019), Minari (2020), Drive My Car (2021), and All Quiet on the Western Front (2022). Oddly enough (maybe there was some change of rules), starting in 1998 with Life Is Beautiful, six of these also got nominated for Best Foreign Language film: Life Is Beautiful, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Amour, Roma, Parasite, Drive My Car, and All Quiet on the Western Front. All of them won in the Foreign-Language category, but only one, Parasite, won Best Picture as well. Presumably if a film was good enough to be nominated for best picture, it certainly would be good enough to win the Foreign-Language Oscar.

The same was true for animated films. Up and Toy Story 3 were nominated in both categories and won just the animation awards. (The animated feature award was started in 2002 for films released in 2001, so Beauty and the Beast could not do the same.)

Now we turn to another way of looking at the Best Picture and Best Animated Feature categories. If one is on Facebook, as I am, or, presumably, other social-media sites, as I am not, in many years one reads many vociferous complaints about the quality of the Best Picture winners. Since online people love lists, there are plenty of people weighing in on the ten worst films to have won that prize. These ten are usually fairly recent, since these online commentators usually don’t watch older films. Occasionally someone mentions Cavalcade (1933), but those are the real cinephiles.

I’m going to compare the Best Picture and Animated Feature nominees and winners, starting in 2002, when the latter category originated (for films released the previous year). The questions are, are some of the animated nominees and/or winners better than the live-action films that won Best Picture in the same year, and if so, how often does this happen? This is not, of course, to say that the Oscars are a true reflection of the cream of the crop, especially in the live-action Best Picture category. The best animated films (at least, English-language) tend to rise to the surface in terms of nominations because there simply are so few of them in comparison.

Logically, having chosen the Oscars as a means of comparison, I should compare all the excellent nominated animated films with all the excellent nominated live-action films. After all, the film or films deserving to win seldom do so. Maybe some of them are better than the animation winner. I’m not going to include all the nominees, because first, it would make this entry more lengthy and convoluted than it already is. Second, I haven’t seen all the nominees in either category, though I have seen a higher portion of the animated ones. Still, I shall mention in parentheses live-action titles that in my opinion were more deserving of the Best Picture Oscar than the actual winner.

I have seen all the animated winners and all of the live-action ones apart from Crash. Thanks to the reviewers and friends who warned me off the latter. (To be honest, I turned Chicago off about twenty minutes in.)

The Face-off

So let’s go year by year and see how the Best Picture fares against the Best Animated Feature–or in some cases multiple nominees in that category.

Going by release years rather than the years when the awards were given, we start with 2001. A Beautiful Mind was the winner. I’ve actually seen it on a list of worst-ever Best Pictures, but I think it’s a fairly good film. Shrek, the animated champ that year, was much admired, but I was disappointed by it. Monsters, Inc., however, was up against Shrek, and in my opinion deserved to win. It’s arguably better than A Beautiful Mind.

There’s no contest for 2002. Even today, awarding a foreign-language film the best-animated prize is nearly impossible–or indeed, a non-Hollywood one. (Non-American winners come from the UK and Australia.) To be sure, many Academy voters probably saw the dubbed version of Spirited Away. Nevertheless, the obvious sheer brilliance of Miyazaki’s film (above) won the day. Indeed, with Godard gone, Miyazaki may be our greatest living filmmaker–though no one can see enough films from around the world to make such a judgment.

2002 was the first year in which there were enough eligible animated features that five rather than three films were nominated, something that wouldn’t happen again until 2009. Nevertheless, the animated competition was pretty lackluster: Ice Age, Lilo and Stitch, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, and Treasure Planet. Spirited Away, arguably one of the greatest films of our current century, is miles beyond Chicago. If there is any evidence that the animated films can top the live-action ones, this year provided it.

Unlike our Supreme Court and other federal judges, I shall recuse myself from judging the 2003 contest. Having written a book on the subject of The Lord of the Rings film franchise and having had extraordinarily generous cooperation from the filmmakers, I can’t really be objective. Quite possibly Finding Nemo is better than The Return of the King,

2004 saw a return to only three animated features–a situation that would last until 2007. Three nominations were enough, however, since The Incredibles was up against Crash, a film high on many lists of the worst-ever winners. I doubt many would dispute my claim that The Incredibles won this face-off by a mile. (Again, I haven’t seen Crash or some of the other nominees, but I very much suspect that Spielberg’s Munich should have won.)

I am less confident in calling the 2005 winner. Million Dollar Baby is a decent film, though I wish Eastwood had not injected the heavy-handed point that Maggie wins Frankie’s heart because she’s a substitute for the daughter who has willfully disappeared from his life. Frankie losing his prejudice against training women boxers would be more powerful if it was simply based on her skill and determination. Still, I hesitate to say that the animation winner, Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (above), is better. (One of the English-language imports that have won.) I am a huge Aardman fan, but Wallace and Gromit work better in the shorts (especially the sublime The Wrong Trousers). Of the other two nominees in the category, Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride isn’t a contender, but one could make a case for Howl’s Moving Castle (Miyazaki again) as the film of the year.

Scorsese’s The Departed is a more complicated case in the 2006 face-off. Those of us who know the Hong Kong film it’s based on, Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Internal Affairs (2002), know how very much Scorsese used from the original. Plus who can forgive that final shot? Being a George Miller fan, I was quite disappointed by Happy Feet (the second English-language import to win). Rather bland, I thought, and certainly no Babe: Pig in the City (1998). I think Cars should have won best animated feature, and it outdoes The Departed as well. For some reason a lot of people don’t like Cars all that much compared to other Pixar films, which I don’t understand. Certainly Cars 2 is awful and Cars 3 pleasant enough. But the original is terrific.

The 2007 contest must be a draw. It’s hard to choose between the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men and Rataouille, the animated winner. (If Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood has won best picture, I would give it the edge over the Pixar film. It’s another of the great films of the current century.)

It’s safer to say that in 2008 WALL-E tops Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan’s Slumdog Millionaire. The first half hour of WALL-E, set on Earth, is perhaps the best thing Pixar has done. It falls apart a bit once the hero and Eve get onto the giant spaceship to which humanity has fled once the Earth became uninhabitable. It turns into a prolonged chase that isn’t nearly as interesting as the incredibly clever exploration of the detritus of civilization that WALL-E diligently searches through in that first half-hour. Still, for that half-hour, I give it the edge against Slumdog Millionaire.

In 2009, there were for the second time five animated nominees. The category would return to three in 2010, but thereafter there have always been five. Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker was probably one of the stronger films to win best picture in the period I’m covering. Still, can it really be said to be better than both Pixar’s Up (the winner) and Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox? And possibly Coraline or The Secret of Kells, Laika’s and Cartoon Saloon’s first entries into the fray respectively. (One benefit of writing this entry is that I watched for the first time all three of Tomm Moore’s lovely nominated Irish films, including The Song of the Sea and Wolfwalkers.)

My case is pretty strong in 2010. With only three nominees, the animated winner, Toy Story 3, easily tops Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech. (We should remember we’re in the period when Harvey Weinstein was bludgeoning his company’s films into the winner’s circle.) Some would say How to Train Your Dragon would as well. (Among the live-action nominees, I would vote for Inglourious Basterds, but it would be a miracle if the Academy members chose such a film.)

With 2011 we reach another case where the best-picture winner is widely decried as among the worst to pick up the trophy: Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist. The line-up of animated entries was pretty weak apart from Rango, directed by, of all people, Gore Verbinski. This brilliant outlier within the animation industry (produced by Nickelodeon), is a sort of cross between Chinatown and Once upon a Time in the West. That’s Rango with the villainous-tortoise mayor, above; the latter is a combination of Noah Cross in Chinatown and Mr. Choo-choo in Once upon a Time in the West.

Rango seems to have largely slipped from people’s memories, perhaps partly because it’s not a Disney or Pixar film that you buy on disc for your kids and have around forever. I don’t know what kids would make of Rango, but it’s definitely more aimed at adults. And hilariously imaginative.

2012 was a banner year for great animated films. The Oscar winner, Pixar’s Brave, was the first of six films in a row from Pixar and Disney, both at that point under the leadership of John Lasseter. I don’t find Brave among the best of these, but it’s OK and it no doubt benefited from all the fuss about it having Pixar’s first female protagonist. For me, there were no fewer than three wonderful nominees that were better: Laika’s Paranorman, Aardman’s The Pirates!: In an Adventure with Scientists! (the British title, changed to the much more boring The Pirates! Band of Misfits for North American release), and Disney’s Wreck-it Ralph. All three offer a flood of clever jokes and original concepts that could only be understood by adults. In Wreck-It-Ralph there’s the AA-style meeting of video-game villains that Ralph attends (top). Or in The Pirates!, the Pirate of the Year awards ceremony that puts the rival contestants in split-screen à la the Oscars show (second from top).

Any of them beats the “best picture,” Ben Affleck’s Argo. Remember that? (I haven’t seen all its live-action rivals, but Lincoln and Amour would have been creditable winners.)

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave fully deserved to win Best Picture. There’s certainly nothing to rival it in the somewhat set of nominations in the animation category. I did not find the winner, Disney’s Frozen, particularly interesting. It seems to be geared to appeal to small children. Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises was the only plausible nominee to go up against Sir Steve’s film, but I’m not going to make that argument. (It’s a real pity that Gravity was in the competition this year, since it truly is a great film and also deserved to win.)

Moving on to 2014, the live-action winner was Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Innocence). The list of animated nominees was not as strong as some years, but I think Birdman is overrated, and Disney’s Big Hero 6 tops it. (I’ve only seen some of the live-action nominees, but The Grand Budapest Hotel and some of the others were pretty strong contenders.)

In 2015 the winners in the two categories were Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight and Pixar’s Inside Out. I don’t really have a preference. (Here’s another case, similar to Inglourious Basterds, of a marvelous but violent, over-the-top masterpiece deserved Best Picture: Mad Max: Fury Road. It pretty much swept the technical awards to end up with six, but Spotlight won only two–picture and screenplay. Go figure.)

I remember watching Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight in a theater in 2016. I sat there thinking that this film was made by a talented young man who someday might win an Oscar. To me, his The Underground Railroad was a more impressive achievement and deserved a slew of Emmys. Three excellent animated films were nominated in 2016: Disney’s Zootopia, Laika’s Kubo and the Two Strings (bottom), and Disney’s Moana. I was convinced that Kubo would finally win Laika it’s first, well-deserved Oscar. Zootopia won over what I think is a slightly better film, Moana, but one can’t really complain in this case. (My preferences for Best Picture would have been Arrival and La La Land.)

The situation was reversed in 2017. Much though I like many of Guillermo del Tor’s films, I’d have to give Pixar’s Coco the edge over The Shape of Water (talk about a Mexican stand-off!). (The true masterpieces among the nominees that year were Nolan’s Dunkirk and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. At least, as so many of my friends have said, Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri didn’t win.)

Now we come to the notorious year of 2018, when Peter Farrelly’s (!) Green Book won best picture against competition that included Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman and Curaón’s Roma. This incomprehensible choice throws an even greater light on the high quality of the animated race that year. Three masterpieces were among the five nominees: Sony’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, which won, Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs (above), and Disney’s Ralph Breaks the Internet. Any one of these rolls right over Green Book. Incredibles 2 is pretty good as well. I enoyed the fifth nominee, Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai, but it hadn’t a chance against these three.

2019 is easy. Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite beats everything, even Pixar’s Toy Story 4. Probably a lot of people agreed with my assessment that the franchise was showing a bit of wear and tear, though not nearly as much as last year’s Lightyear. (Again, it’s a pity that two other masterpieces nominated that year couldn’t also win: Little Women and Once upon a Time in Hollywood.)

For 2020, when theater-going was difficult if not impossible, studios delayed many films or sent them straight to streaming. The result was a somewhat uninspired lineup of animated nominees. Soul almost inevitably won. I must admit that I preferred Pixar’s films as they were until recently–adventures of various sorts, whether involving actual superheroes, groups of toys, or an old man flying his house to South America to learn how to be sociable again. These had psychological depth, but they didn’t make it explicit by making emotions into characters or sending them to heaven. So Nomadland comes out ahead this time. (I would have preferred two other nominees, The Father or The Trial of the Chicago 7.)

In 2021 I found Sian Heder’s Coda as heartwarming as anyone, but Oscars are purportedly for picking great films that we assume till be watched in the future as classics. Not that they get it right very often, but, well, Oscar-bait ain’t what it used to be. The Danish animated documentary Flee leaves us with a tear in the eye as well, but the Academy stuck to its long habit of rewarding Pixar and/or Disney films and made Encanto its top animated film. This film had many good moments, but it annoyed me every time it got into a lively scene. Suddenly the characters (and virtual camera) started zipping about through the settings. Those settings were gorgeous, but we didn’t get a chance to look at them. Just compare it with Moana, which also had scenery worth lingering over while still managing to drip with exuberance. (For the live-action champ, I would have gone for Nightmare Alley, The Power of the Dog, or West Side Story. It was a pretty good year.)

There was, however, one animated feature nominated that year: the unmissable The Mitchells vs. the Machines–though many may have missed it when during the pandemic it skipped theatrical and went straight to Netflix. It was produced by Phil Lord and Chris Miller, who also did Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse for Sony Pictures Animation, and although a very different film, it has all the energy, imagination, and craziness of that film. It also plays out the potentially apocalyptic rebellion against humans by AI and the robots run by it. The premise is that an angry computing system being replaced by a new generation sends robots to put all humans in plastic cubes and fire them into space–including its own inventor. The dysfunctional Mitchells are humanity’s only hope. The funniest and most telling scene is when they stop at a mall and all the products in the stores, which have chips installed holding a kill order to destroy the family, start attacking them. This culminates in a bunch of Furbies going after them, led by the world’s largest Furby (above).

What happened in the 2022 category is sort of like what happened in 2002, when Spirited Away won. An outlier from outside the traditional Hollywood studio structure (Netflix) was nominated among a somewhat weak group of animated films and won the day. I settled down to watch the broadcast of the ceremony wondering if Academy members would recognize what a remarkable film Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio is and not just reflexively vote for the Pixar film. That was Turning Red, which got a lot of attention for daring to show a teenager hitting puberty and experiencing her first period. I didn’t think it was a very good film and confirmed my sense that Pixar has declined in recent years. It’s probably better than The Good Dinosaur and now Lightyear, which is not saying much. (Carolyn Giardina’s recent “Elemental Steps into the Ring in Major Box Office Test for Pixar,” astutely sums up reasons for the aesthetic decline of Pixar–and, one might add Disney Animation.)

I know a lot of people for some reason are enthralled by Everything, Everywhere, All at Once, which won the 2022 Best Picture. I found it mildly entertaining but at least it gave Michelle Yeoh a career win for Best Actress. Pinocchio is miles beyond it. (Everything won against a slew of superior films. In alphabetical order: The Banshees of Inisherin, The Fabelsmans, Tár, and Women Talking.)

Totting up the live-action vs. animation winners in this face-off, we find one recusal, one draw, five decisions in favor of the live-action winners and fourteen for the animated winner or one or more of the animated nominees. As I mentioned at the start, the figures would be quite different if I had compared all the Oscar-worthy animation awards with all the Oscar-worthy Best Picture nominees. Still, in general this comparison may suggest that animated films are unfairly treated as one of the minor categories that people don’t pay much attention to.

I’m not suggesting that the Academy change their categories or rules. There’s probably no way to boost the prestige of the Animated Feature nominees.