Monday | August 6, 2018

DB here:

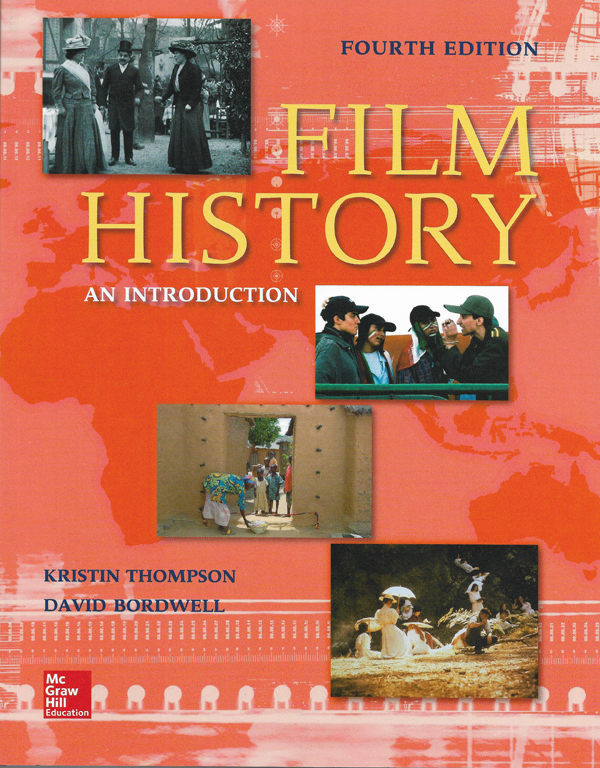

After nine years, here comes another Thompson/Bordwell boulder: Film History: An Introduction in a fourth edition.

When I was in college (1965-1969) my university offered no courses in film. The year after I graduated, two courses appeared: one, a survey history, the other a study of adaptations. Those pretty much defined the early zones of film studies on most campuses.

In the 1970s, however, the survey history was supplemented by a survey of film aesthetics (sometimes called “film language”), which organized the course not chronologically but conceptually. Weekly topics took up categories like “editing” and “acting,” and usually something about adaptation. Eventually the aesthetic survey became more popular than the historical overviews, and often it served as the introductory course for a major. (Film majors were starting then too.)

It’s likely that our textbook Film Art: An Introduction (1979) contributed to the rise in aesthetic surveys. For reasons rehearsed here, we tried to make it more comprehensive and in-depth than earlier books of that type. We tried to synthesize the ideas developed by film researchers about narrative, filmic modes (documentary, animation), authorship, genre, and film as a vehicle of ideology. We also floated ideas about form and style we developed in our research. Film Art‘s approach proved influential; many later books adopted our conceptual layouts, our terms, and our explications of techniques.

We also tried something that wasn’t common in other “film-language” texts. We included a chapter surveying film history. It was short and very selective, of course, but we tried to show that the expressive resources we surveyed conceptually could also be understood as part of a larger historical dynamic.

About a dozen years after the first edition of Film Art, we published our own version of a synoptic film history. Again, we tried to incorporate film research as we understood it, and—

But wait. I already wrote this, back in 2009. To save you a click, let me quote myself, with some light modifications.

The 1970s: More than disco

Star Wars Uncut: Director’s Cut (Casey Pugh et al., 2010).

For a long time, and sometimes still, film histories written by Americans took a very partial look at the phenomenon of cinema. For one thing, they tended to focus on a series of masterpieces, films that had been deemed important within a narrow canon. The earliest lineup went pretty much this way: Lumière films, Méliès’ Trip to the Moon, Porter’s Great Train Robbery, Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and/ or Intolerance. Then came national schools, such as German Expressionism (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), Soviet Montage (Battleship Potemkin), and Continental Dada and Surrealism (Entr’acte, The Andalusian Dog). Early sound was M and Sous les toits de Paris and maybe Love Me Tonight. The 1940s was Grapes of Wrath and Citizen Kane and Enfants du Paradis and Italian Neorealism. And so on.

But in the 1970s archivists began opening their doors to researchers. Thanks to wider and deeper viewing, new film historians, young and old, were questioning the canon. André Gaudreault and Charles Musser showed that Porter’s Life of an American Fireman, which supposedly gave birth to crosscutting, did not do so; in fact the version people had used for years was a re-cut print! In Jay Leyda’s seminars at NYU, young scholars like Roberta Pearson were tracing what Griffith actually did and didn’t do, a task taken up by Joyce Jesionowski as well. At the same time, Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Noël Burch, and others began questioning the idea that “our cinema” developed step by step from “primitive” beginnings. In England, Ben Brewster, Barry Salt, and others were minutely analyzing changes in film technique in the earliest years. Here at Madison, Tino Balio and Doug Gomery were revising the study of Hollywood as a business enterprise. Specialists working on national cinemas, from Russia, Italy, and the Nordic countries, were showing that there was far more diversity in world cinema than was dreamt of in orthodox histories.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution. She also studied particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I studied European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

That’s what made our task perilous. Everything, it seemed, needed to be rethought.

Most obviously, countries outside Europe and North America had been neglected. Our book was, I think, the first synoptic history in English to make use of statistical information on production and exhibition, and the numbers brought out a striking omission.

In the mid-1950s, the world was producing about 2800 feature films per year. About 35 percent of these came from the United States and Western Europe. Another 5 percent were made in the USSR and the Eastern European countries under its control. . . . Sixty percent of feature films were made outside the western world and the Soviet bloc. Japan accounted for about 20 percent of the world total. The rest came from India, Hong Kong, Mexico, and other less industrialized nations. Such a stunning growth in film production in the developing countries is one of the major events in film history.

Traditional histories, and film history textbooks, had virtually ignored the bulk of film-producing nations. Only one or two major directors would step in from the shadows. Kurosawa summed up Japan, Satayajit Ray stood in for India. And the books’ layout of chapters indicated this second-class status.

The history of film was portrayed as Euro-American, with East Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa, appearing, if at all, in periods when westerners first got glimpses of their film culture. So Japan was typically first mentioned after World War II, when Rashomon won a prize at the Venice Film Festival. One would hardly know that there were many, and many great, Japanese filmmakers working in a long-standing tradition.

As if this weren’t enough, we were determined to include other varieties of artistic filmmaking. Documentary cinema, animation, and experimental film had attracted subtle historians like Bill Nichols, Mike Barrier, and P. Adams Sitney. We weren’t experts in these areas, but we were keenly interested in the debates in that domain, and so, guided by these and other scholars, we sought to integrate the histories of documentary, avant-garde, and animated cinema into our survey.

1980s-2000s: Kristin and David’s excellent adventure

Kristin at Bonded Storage, Fort Lee New Jersey.

In sum, we decided that we could write a plausible international history of cinema—not a be-all and end-all, but a new draft that reflected the rich variety of new findings and fresh perspectives. Like all historians, we had to be selective. We couldn’t, for instance, track every nuance of the “false starts and detours” in early film technique. More globally, we decided to concentrate on three lines of inquiry.

First, we studied changes in modes of film production and distribution. This inquiry committed us to a version of industrial history. How filmmaking was embedded in particular times and places, how it connected to local culture and national politics: these factors affected the ways films were made and circulated. For example, the early distribution of films followed the trade routes of late nineteenth-century imperialism. That global system started to crack with the start of World War I. A new world power, the United States, became the major film exporting country—a position it has enjoyed for most years since then.

Secondly, we studied changes in film form, style, and genre. We treated these artistic matters as not wholly the products of individual innovators but also as more widely-developed practices and norms. This emphasis on norms allowed us to link, in some degree, the development of technique to opportunities and constraints presented by film industries.

This angle of approach also meant looking at older works with a fresh eye, informed by others’ research but also by our own interests in film as an art. We were obliged to seek out films lying outside the orthodox story. Birth and Caligari and M featured in our account, but so did The Cheat and Liebelei and Assunta Spina (1913, below). In those pre-DVD days, few of the titles we sought could be found on video, but we preferred to watch film on film anyway.

So it was off to the archives. Fortunately, many collections were wide-ranging. We saw Egyptian and Swedish films in Rochester, French and Italian films in London, Indian and Japanese films in Washington, D. C., Polish and African films in Brussels. Committed to documenting our claims with frame enlargements, not production stills, we were lucky to be able to take photos from many of the movies we saw.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

For example, we could point to the emergence of tableau cinema in many countries in the 1910s. We could consider various models of state-controlled cinema in the 1930s and discover the “New Waves” that emerged not only in France but around the world in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Citizen Kane popularized a “deep-focus” look, but comparative study showed us that its principles were prefigured in Soviet cinema of the 1930s and spread to most major filmmaking nations in the 1940s.

Not all trends march in lockstep, but there was enough synchronization to let us plot broad waves of change across the 100 years of film. Our aim was a truly comparative film history.

As a kind of overarching commitment, we wanted readers to think about what historical processes had shaped earlier writers’ frames of reference. How, for instance, did the “standard story” and the mainline canon get established in the first place? Part of the answer lies in the growth of film journalism and film archives. Why did Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, and other directors get so much fame in the 1950s and 1960s? True, they made exceptional films, but so did many other directors who remained unknown to a wider public. We suggested that the “golden age of auteurs” owed a good deal to developments in film criticism and to the postwar growth of film festivals.

What led Japanese anime to a period of international popularity in the 1980s? Not only worldwide television distribution, but also devoted fans who spread their gospel through videocassettes, the youthful Internet, and such fanzines as Protoculture Addicts and Mecha Press.

In general, the “institutional turn” in film research of the 1970s and 1980s pushed us to consider how film industries and international film culture governed the way films were made and circulated.

The research programs that were launched in the 1970s were characterized by a greater self-consciousness than we had seen before. Historians questioned their assumptions and explanations. Why attribute originality only to “great men” without also examining their circumstances? Why presuppose that film technique grows and progresses in a linear way? To capture this new self-consciousness about purposes and methods, we incorporated something that had never been seen in a film history before: an introduction to historiography. Originally in the printed text, in its latest incarnation it can be found elsewhere on this site.

We also appended to each chapter short “Notes and Queries” discussing intriguing side issues, debates in the field, and topics for further research. Those were put online for download. The third edition’s are here; sample them through the “Choose a Chapter” dropdown menu. The fourth edition’s updates will soon be available.

2018: Results just in

Tangerine (Sean Baker, 2015).

The first edition was published by McGraw-Hill in 1994, a second edition in 2002, a third in 2009—when I wrote the sections you’ve just read. Now we have a fourth edition, published in June. After ten years or so, what’s changed?

We have the same chapter breakdown. Part One deals with Early Cinema, from the beginning to the end of the 1910s. Part Two surveys the late silent era to 1929. Part Three considers the sound cinema up to 1945. Part Four considers post-World War II filmmaking, through the 1960s. Developments from the late 1960s are reviewed in Part Five. The last part deals with the age of New Media, including analyses of changes in Hollywood, the rise of globalization, and the emergence of digital technologies.

We’ve incorporated new lines of research in some early chapters. The chief change involves Alberto Capellani, a director who was little-known before a retrospective at Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna brought many of his works to attention. He worked between 1905 and 1922, making extraordinary films like L’Assommoir (1909) and Germinal (1913), discussed here by Ben Brewster. In the new edition we contrast Capellani’s delicate staging within the shot to the editing-oriented approach of his much more famous contemporary D. W. Griffith. This is the sort of historical contextualizing we’ve striven for in all the editions of the book.

Likewise the availability of films on DVD has enabled us to explore fresh examples of films in the Young German Cinema, the Japanese New Wave, and other movements. We didn’t give up on 35, though. A lot of frames still come from prints. For example, thanks to Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, we were able to obtain a frame from Med Hondo’s extraordinary West Indies.

As you’d expect, the bulk of new material comes in the final stretches. In Chapter 24, we incorporate discussion of The Missing Picture, The Act of Killing, the work of Wang Bing, and the emergence of the animated documentary (Waltz with Bashir, Tower). Our survey of experimental cinema widens to include Liu Jiayin’s work (a favorite of the blog), as well as films by Chick Strand, Marlon Riggs, Phil Solomon (ditto), and Mark LaPore, along with internet experiments like Matt Bucy’s Of Oz the Wizard (2016).

In considering national cinemas outside Hollywood, we catch up with industrial developments in Europe and Russia. Naturally, we take account of new talents, such as Serge Loznitsa and the directors of the Romanian New Wave. The last edition spotlighted many directors still powerful on the international stage, from Almodóvar and Haneke and Denis to Herzog and Varda, but I’m glad we found room for updates on Oliveira and Alexei German, whose beyond-bleak Hard to Be a God (2013) is one of the most tactile films I’ve ever seen.

What do we do with “slow cinema”? We treat it as a development out of classic art-cinema strategies of prolonged duration and “dead time.” We also counterpose it to the nervous “free-camera” style on display in films like Gomorrah (2008) and Toni Erdmann (2016). Our approach to cinema remains comparative, showing how creative alternatives can operate in the same historical period.

DVD availability allowed us to expand our treatment of Nollywood in Chapter 26. There we also trace the emergence of Iran’s Asghar Farhadi (I still admire About Elly) and Cuba’s Fernando Pérez. We’ve especially widened our treatment of Indian cinema, which not only dominates its local market but, in the period since our last edition, has emerged with international successes. I was also happy to learn, thanks to the advice of Lalita Pandit and Patrick Hogan, of the striking films of Rituparno Ghosh. (This hallucinatory scene is in The Last Lear, 2007).

Chapter 27, devoted to Pacific Asia and Oceana, brings those national industries up to date while discussing Taika Waititi, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and others. Of course we retain considerations of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Hong Sangsoo, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and many other major artists. Our box on Sony, which I always liked, has been exiled to the Notes and Queries online, the better to make room for a box in which we pay tribute to the great Hayao Miyazaki. And of course our section on China has been largely redone, to reflect its rise to international power. We analyze how government officials and private investors leveraged a minor national industry into one of the filmmaking behemoths of our time. Not that it always goes well, as The Great Wall (2017) showed.

Similarly, Hollywood changes so fast that we needed to recast many stretches of Chapter 28’s survey. But the search for synergy across conglomerate domains, the shift from one-off blockbusters to franchises, the impulse toward mergers and acquisitions that marry “content” to delivery systems (cable, the internet): these and other business strategies emerged in even sharper relief ten years after our last edition. Fortunately for our timing, the acquisition of Fox by Disney began while the book was in press, so we were able to sneak that initiative into a new box devoted to the Disney empire. Too bad we didn’t have this frame from Ralph Breaks the Internet: Wreck-It Ralph 2 to illustrate that.

Of course American cinema is more than the studios, so we’ve updated our consideration of indie films, with discussions of auteurs, genres, and trends. (Yes, Wes Anderson and Damien Chazelle are involved.) The third edition considered Mumblecore; now we’ve got coverage of directors like Lena Dunham moving to television and streaming.

Chapter 29, on globalization, runs through several trends that are still with us, from piracy and festivals to diasporic filmmaking and the multiplex strategy. We consider how worldwide fan culture has exposed new possibilities of filmic expression, through mashups, video essays, and DIY exercises like Star Wars Uncut: Director’s Cut (2010).

The chapter also analyzes how countries outside the US are trying to make international hits. The Europeans mostly sought to do this through art-cinema channels, while other countries found some success with popular entertainments. Baahubali 2: The Conclusion (2017) garnered $81 million outside India.

Chinese filmmakers have become less reliant on exports, since the stupendous growth of the exhibition sector created a mega-market at home. A hit like Wolf Warrior 2 (2017), which was reported as earning over $850 million, can rival Hollywood’s global revenues within a single territory. Interestingly, the popular successes are often heavily indebted to Hollywood: Baahubali 2 owes a great deal to 300 and other special-effects-heavy spectacles, while Wolf Warrior 2 revives the action style and conventions of Rambo and Mission: Impossible.

For the previous edition, we added a final chapter on digital technology’s impact on cinema. That was as up-to-date as we could make it in the late 2000s, but obviously our treatment needed a big makeover. In Pandora’s Digital Box, I traced how digital tools entered cinema. For FH 4.0 we update that by tracking the changes in preproduction and postproduction, in early efforts to shoot digital, and then in more ambitious production possibilities, along with internet publicity and marketing. We then cover digital convergence, chiefly through Hollywood’s Digital Cinema Initiative’s effect on theatre conversion and digital production.

Naturally, we also analyze some of digital technology’s effects on film form and style: the possibilities of 3D, the opportunities for longer takes and photographic experimentation, and the new prominence of digital animation. A box contrasts David Fincher, whose embrace of digital yielded new possibilities for classical storytelling, with—who else?—Jean-Luc Godard, whose digital work such as Éloge de l’amour (2001, below) challenges just that tradition.

The convergence story wraps up by tracing how digital distribution, beginning with the DVD and passing through online distribution, arrived at piping films directly to theatres. The chapter ends by looking at how the Internet, video games, and Virtual Reality have interacted with modern cinema.

Our emendations and updates bring home to me the advantages of seeing change against a background of continuity. The film industry replays time-honored business strategies, such as the impulse toward vertical integration. Amazon and Netflix, not content with controlling distribution and (home) exhibition, move into production to assure themselves of a flow of product—just as 1910s exhibition chains created studios to supply their screens. And as I write this, the 1948 consent decrees are being reconsidered as anachronistic.

Likewise, filmmakers of the 2010s confront choices about technique familiar from earlier eras. Since a digital shot can be indefinitely long, when should I cut? I can reframe a shot in postproduction, but I still have to decide on the shot scale. With highly spatialized sound in theaters, where should I locate this effect? Even with new technologies and changing circumstances of reception, the basic demands of form and style persist.

Here’s a taste of our conclusion:

Digital convergence worked hand in hand with globalization and the power of the American studios. The top Hollywood pictures were successful in most countries, and they could be delivered on many platforms. But in the swift media churn, with new formats coming up all the time, would traditional filmmaking die?

Evidently not. For one thing, the number of feature films was surging. In 2002, the world made over 4,000 feature films. In 2016, that number was over 7600. This vast output included blockbusters, modest independent films, and every form in between. The boom took place in the face of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. It happened despite the fact that a handful of American blockbusters ruled nearly every national market.

But perhaps theaters, the public side of film culture, were in danger? Just the opposite. Screen growth was robust through the 2010s. In 2016, the world had over 163,000 screens. Even without counting the millions of television monitors, computers, and mobile devices, there were far more movie screens than ever before. And plenty of people wanted to visit them. The year 2015 set a record high in worldwide attendance, 7.4 billion admissions. This amounted to about one ticket for every man, woman, and child on Earth.

Digital convergence, boosted by globalization, encouraged the spread of cinema. Personal computers, the Internet, mobile phones, game consoles, tablets, and portable music devices initially could not display films, but all were eventually adjusted to do that. Film wriggled its way into every media device that came along. From broadcast television and videotape to DVD and streaming, films spread beyond the theater. They entered our living rooms and went with us anywhere. Today, more people are watching more hours of motion pictures than at any other time in history. As newer technologies emerge, we suspect that they too will serve the cinematic traditions that have developed over 120 years.

Optimistic, eh? Yep, that’s us. We know that the book is far from perfect, and we’ll be trying to correct mistakes and misjudgments. Still, we hope that Film History: An Introduction tells a story that will encourage young filmmakers and filmgoers to embrace all the traditions of cinema. Those traditions have fascinated us for fifty years, and we hope to communicate some of our enthusiasm to readers.

Film History: An Introduction’s fourth edition is available in several formats, some frankly innovative. To understand why, it’s useful to try to answer the constant question: Why are college textbooks so expensive?

There are plenty of factors to consider, of course, but I want to focus on just one. Much of what follows is my personal speculation, but I think it makes sense if we entertain the prospect that people can act as rational agents.

The professor rationally decides that she wants her students to read a specific book in order to study aspects of the subject. She assigns it.

Some students will decide to borrow a copy, check out a library copy, or risk not reading the book at all. Those are all justifiable courses of action. But many students, deciding that owning the book will help them succeed in the course, buy it. Still, (a) it’s pretty expensive; and (b) they may not wish to keep it after taking the course. Textbooks are among the few books which users are forced, more or less, to buy.

Many students want to recoup part of their investment, so they resell the book for what they can get. Jobbers and campus bookstores buy the books and resell them to new students. Those folks, themselves rational agents, are glad to get a lower price. I speak as someone who’s bought thousands of used books, including textbooks.

But the publisher and authors reap no rewards from a resale, which replaces the purchase of a new copy. It seems likely (though I have no evidence that this shapes our or any company’s decisions) that publishers assume that nearly all purchased textbooks will be resold. Therefore, in order to maintain profitability, the publisher could set the price (wholesale/retail) at a point that will offset at least one future resale.

So the real cost to the student is the difference between what she pays initially and what she can get on buyback. A $100 textbook might be sold back to the bookstore for $25 or $30. If it’s in decent shape, it could be resold for $60 or more. The money the store gets doesn’t flow back to the publisher, and the student in effect rented the textbook for $70-$75. So the real cost to the student is the difference between what she pays initially and what she can get on buyback. A $100 textbook might be sold back to the bookstore for $25 or $30. If it’s in decent shape, it could be resold for $60 or more. The money the store gets doesn’t flow back to the publisher, and the student in effect rented the textbook for $70-$75.

This has all the marks of an arms race. If publishers raise prices to offset resales, this gives purchasers a greater incentive to resell, thus flooding the market with more used copies. Publishers could also speed up the revision cycle, hoping that new editions will render the old ones less desirable.

I stress that this line of reasoning is my own thinking. Yet it’s evident that the textbook market has presented accelerating prices and triggered growing resentment among faculty and students. Even college administrators have joined the complaint about price rises. (Said administrators aren’t usually inclined to lower tuition, however.) In recent years, the pressure got more intense thanks to two other factors: digital piracy and Amazon.

Start with piracy. Once pdfs of a textbook show up online, publishers suffer big losses. That could prod them, as rational agents, to raise the purchase price. (Lowering the price might seem a way to undercut pirate copies that are sold, but you can’t make the book cheap enough to make a difference.) In effect, when somebody buys a textbook they’re helping subsidize someone else’s download. This creates an incentive for rational agents to download the text themselves, thus pushing the price of the physical book ever upward.

As for Amazon: In past decades, the used-book jobbers were quite adroit at distributing used copies to campus stores, but Amazon’s online model proved far more efficient. Moreover, Amazon revived the long tradition of renting books, and the economies of scale made it easy. As rational agents, the Amazonians bought copies from the publisher and then offered them for rent.

Other companies rent textbooks too, on a smaller scale. In all cases, renters are vulnerable to the frailties of human nature. You can read sad stories of renters who failed to return the book in a timely fashion and ran up charges greater than the cost of a straight purchase.

Publishers have responded to Amazon’s rental initiative by launching rental programs themselves. This is what McGraw-Hill has done with our book.

Let’s go through the options. If you go here and then click on “Print/ebook” and “Bundles,” you can see them all.

Film History exists in both digital and print form. The digital edition may be bought or rented. There’s also the option to fold the e-book into a broader platform called Connect, which gives access to a rich array of material: study aids, an ebook format, questions, video supplements, and more.

The book exists in hard copy as well. It can be rented as a bound volume. Alternatively, it can be bought in a loose-leaf version. If I were buying it, that’s the format I’d pick.

Prices across all these options range from rentals for $60-$80 and purchase for $118–$130.66 and mixtures of both for up to $150.

What about buying the bound version? As you’d expect, that’s the most expensive option. McGraw-Hill offers bound copies on a rent-to-own basis. As I understand it, the customer first rents the book and if she decides to keep it, she pays the rest of the full price. That price is currently $229, a lot, but following my line of reasoning, that price would offset possible resales.

Anecdotes suggest that film majors hang on to their books and try to build personal libraries. If that’s true, I’m happy, for more than one reason. And I learn that Film History will continue to be sold in bound copies outside North America. In my experience, overseas students don’t complain as much about the cost of books, perhaps partly because they attend schools that have low or no tuition fees.

Would I prefer the old days, when you just bought the book and owned it or sold it or gave it away? As a book collector, I would. But Kristin and I are old, old school; we have thousands of volumes in our library. (Many of those won’t be online in our lifetime.) And we also have dozens of e-books, which are great for ephemeral reading or sturdier research. We recognize that publishing, and authoring, are changing because of technology and social dynamics, and so we adjust. The main thing is to get ideas and information and opinions out there for our readers to consider.

For this edition of Film History: An Introduction, we want to thank the staff at McGraw-Hill Higher Education: our editors Sarah Remington and Alexander Preiss, and their colleagues Jen Thomas, Anju Joshi, and Ann Marie Janette. They have helped us make this edition something we’re very proud of.

Sita Sings the Blues (2008, Nina Paley).

Posted in Books, Film history |  open printable version

| Comments Off on FILM HISTORY: AN INTRODUCTION: Not back to the future but ahead to the past open printable version

| Comments Off on FILM HISTORY: AN INTRODUCTION: Not back to the future but ahead to the past

Monday | July 23, 2018

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here. After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

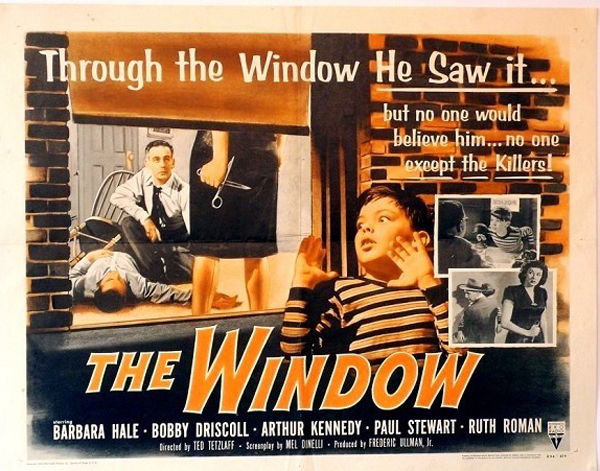

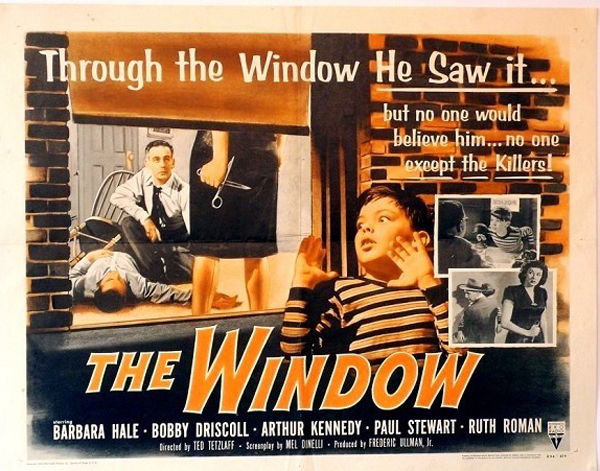

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book: Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

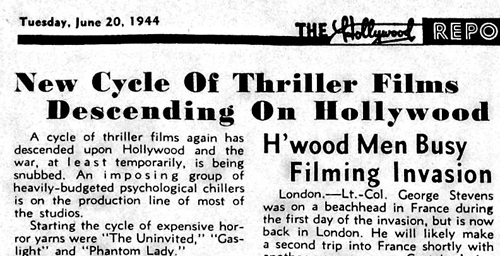

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

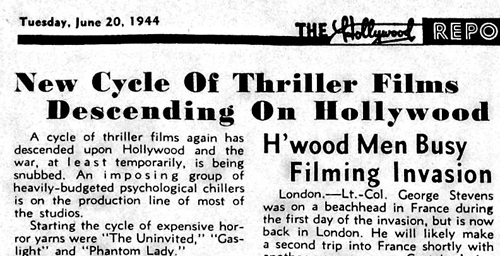

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

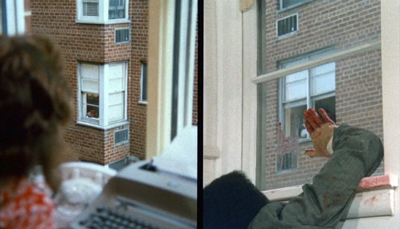

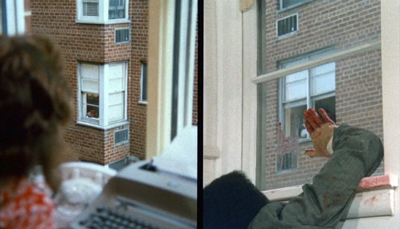

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

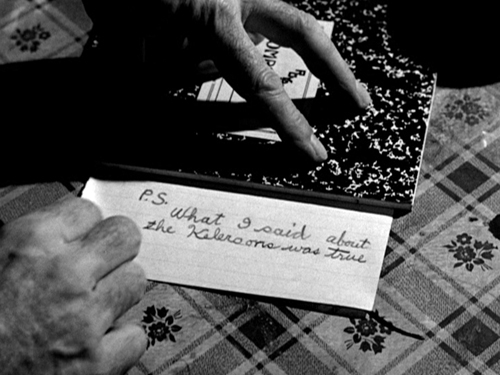

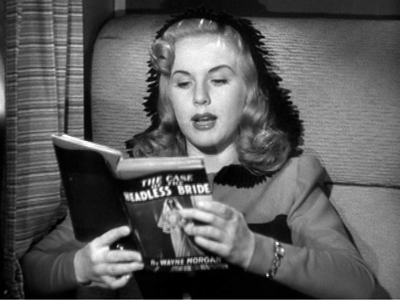

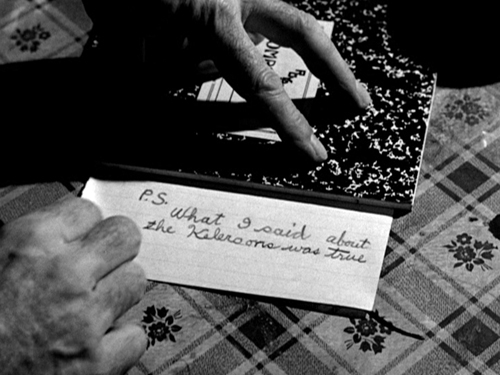

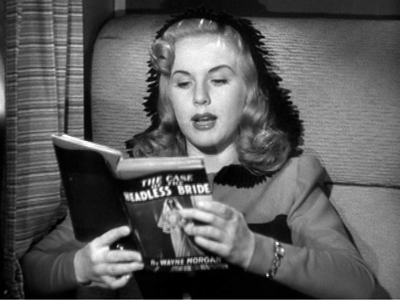

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

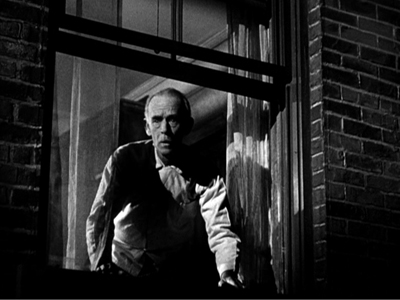

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

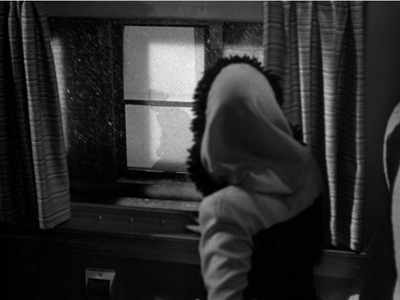

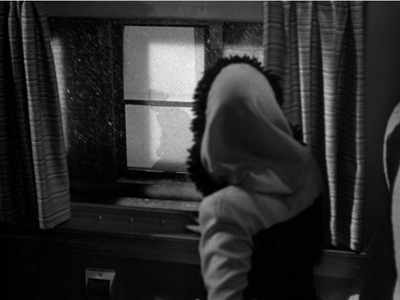

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

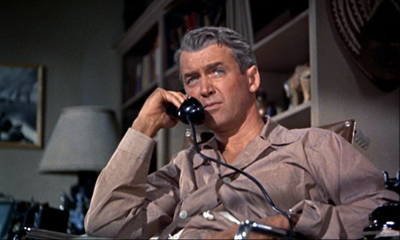

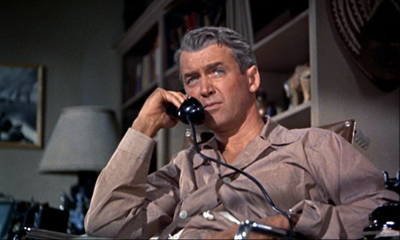

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

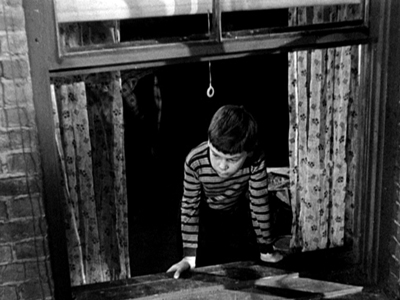

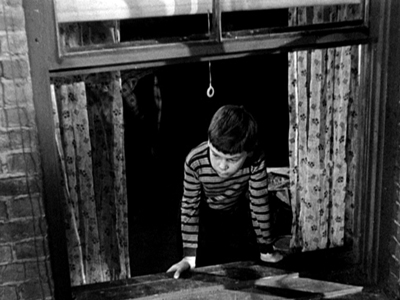

At the window, and outside it

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

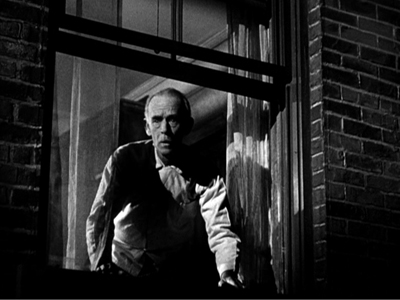

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

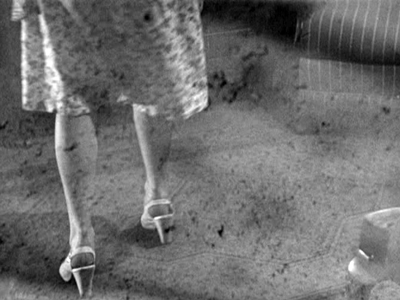

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

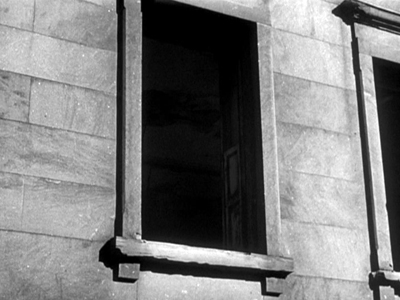

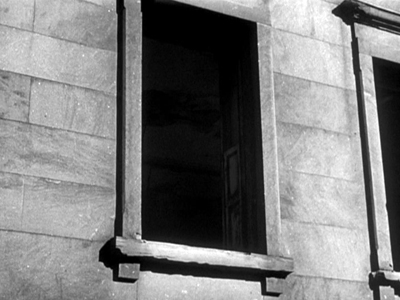

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

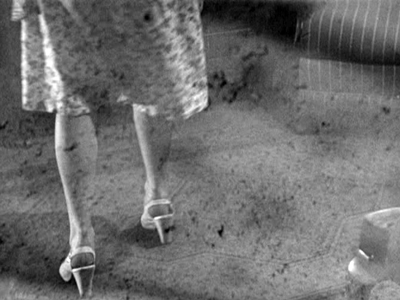

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.

With its goal-directed protagonist and trim four-part plot structure, The Window is a completely classical film. As often happens, a forgivably flawed character gains our sympathy by being treated unfairly but triumphs in the end. And in the film’s integration of dramatic and pictorial elements, its alternation of subjectivity and wide-ranging narration for the sake of suspense, it nicely illustrates some ways in which 1940s filmmakers recast classical traditions for the thriller format and opened up new storytelling options.

Woolrich’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is available under the title “Fire Escape” in Dead Man Blues (Lippincott, 1948), published under the pseudonym William Irish. Woolrich, ever the formalist, initially gave “It Had to Be Murder”/”Rear Window” my dream title: “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” An earlier Woolrich story, “Wake Up with Death” from 1937, flips the viewpoint: A man emerges from drunken sleep to discover a murdered woman at his bedside and gets a call from someone who claims to have watched him commit the crime. Then there’s “Silhouette” from 1939, in which a couple witness a strangling projected on a window shade. See Francis M. Nevins, Jr.’s exhaustive Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988), 158, 186, 245. There are doubtless many earlier eyewitness thrillers, which the indefatigable Mike Grost could tabulate.

The screenplay by Mel Dinelli that I consulted, with help from Kristin, is a rather detailed shooting script dated 23 October 1947. It is housed in the Dore Schary collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Dinelli benefited from the thriller boom in his screenplays for The Spiral Staircase, The Reckless Moment, House by the River, Cause for Alarm!, and Beware, My Lovely.

There are plenty of discussions of thrillers on this site; try here and here. Apart from the chapter in Reinventing Hollywood, you can find overviews here and here. See also the category 1940s Hollywood. I discuss the sort of plot fragmentation characteristic of some current Hollywood cinema, built on 1940s premises, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

For more images from my summer movie vacation, visit our Instagram page.

P.S. 24 July: Thanks very much to Bart Verbank for correcting my embarrassing name error in Rear Window! Also, if you’re wondering why I didn’t mention the very latest instantiation of the the eyewitness plot, A. J. Finn’s Woman in the Window, it’s because (a) I haven’t read it; and (b) I resist reading a book with a title swiped from a Fritz Lang movie.

DB accepts a fine Kriek from the Antwerp Summer Film College team: David Vanden Bossche, Tom Paulus, Lisa Colpaert, and Bart Versteirt.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Directors: De Palma, Directors: Hitchcock, Directors: Koepp, Film genres, Film history, Narrative strategies, Narrative: Suspense |  open printable version

| Comments Off on The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt open printable version

| Comments Off on The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Tuesday | July 17, 2018

Behind the Door (1919).

Kristin here:

David and I have moved house recently, which has caused a long lag in my getting around to doing a DVD/Blu-ray roundup of recent releases. Some are not so recent anymore, but I shall call attention to them nonetheless.

Behind the Door (1919)

Our friends at Flicker Alley have been busy, as usual.

Way back in February of last year, they released Behind the Door, a notoriously grim and brutal drama of World War I that long survived only in incomplete form. Using tinting rolls from the Library of Congress, some scenes from star Hobart Bosworth’s collection, and a re-edited Russian distribution print, as well as a copy of the continuity script, the restoration by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the Library of Congress, and Gosfilmofond approximates the original American release version fairly closely. (Two brief missing sections are filled in by photos and the texts of the original titles.) The tinting and toning, based on the Library of Congress material, is authentic and effective (see top), as is the new score by Stephen Horne.

The Russian version is included in the two-disc set, so we have one of those rare cases where it is possible to compare the foreign and domestic versions–to a degree. Most of the shots, of course, were made with a second camera, and there are inevitably differences of framings and even takes between those versions. Given that the new restoration depends heavily on the Russian print, the comparison must be made primarily on the basis of the differences in the order of the scenes and the other narrative changes made by the Russian editors.

Behind the Door tied for Best Single Release in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s DVD Awards, announced just last month. Congratulations to Flicker Alley and to other organizations we have ties to, which also won awards. The Criterion Collection tied for Best Box Set for its 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912-2012. This massive set (32 discs on Blu-ray, 43 on DVD) contains 53 films, including those by Leni Riefenstahl, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch, Carlos Saura, and Miloš Forman. Belgium’s Cinematek won Best Discovery of a Forgotten Film for its Marquis de Wavrin (1924-1937), actually a series of films shot in South America by this major anthropologist and filmmaker. German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (from the BFI and the Imperial War Museum), which David commented on last year, won Best Special Features.

Das alte Gesetz (1923)

I have a particular interest in German silent cinema of the post-World War I era, so I was happy to see Flicker Alley’s release of Ewald André Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (“The Ancient Law”). Most people know Dupont only from his most famous and successful film, Variety (1925), known for its spectacular camera movements taken from trapezes.

Dupont had a long career, however, starting as a scriptwriter in the 1910s and becoming a director as well in 1918. Das alte Gesetz is mainly known as one of a small group of Jewish-themed films made in Germany in the period 1919-1924. More familiar to most would be Der Golem:Wie er in der Welt kam, co-directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (1920) and to some, Die Gezeichneten, Carl Dreyer’s first German film (aka Love One Another, 1922). A helpful essay in the accompanying booklet by Cynthia Walk gives the political context of die Judenfrage (“the Jewish question) as it was being debated in Europe at the time.

Set in the 1860s, the film concerns Barush, the son of a rabbi in a shtetl in western Russia. He suddenly and somewhat implausibly conceives a desire to leave home and become a famous actor. Naturally his father disowns him. Joining a small traveling troupe, Barush ends up in Vienna, where an archduchess, played by Henny Porten, is impressed by his performance as Romeo and attracted to him as well. She arranges for him to join her court-theatre troupe, where he becomes a star as a classical actor.

The scenes in the shtetl (above) are done with considerable attention to authenticity and without the sort of ethnic humor that one might expect. Although Barush encounters prejudice in Europe, he does not evenually learn a lesson about assimilation and go back to his home with his tail between his legs. Far from it; his father is induced to read Shakespeare and suddenly realizes that there are indeed more things in heaven and earth than he had dreamed of in his philosophy. A happy reunion results, and Barush continues his career.

Das alte Gesetz was clearly a big-budget period piece, with several large sets. Moreover, the influence of classical Hollywood films, which began to be shown in Germany in 1921, is quite apparent. Dupont has mastered three-point lighting and analytical editing, including shot/reverse shot, as this scene between Barush and his father demonstrates.

Barush is played by Ernst Deutsch, a major actor of the day, including in Expressionist films. He’s the rabbi’s son in Der Golem as well, and he plays the bank-cashier protagonist in Karl-Heinz Martin’s From Morn to Midnight.

MOD

Flicker Alley has also developed a healthy list of manufactured-on-demand titles. Many of these are out-of-print films from the Blackhawk Collection. The 51 titles currently on the list include many silent classics, some of them difficult to see on disc otherwise, such as Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle and Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa.

The new offerings lately have branched out somewhat to include more recent films. On September 3 of last year, the company released Alex Barrett’s London Symphony (2017) for its home-video debut. In the press release for the disc, the director describes it as “a love letter to a city, but it is also a film about life in the modern era.” As the title indicates, Barrett places his film in the city symphony genre, and its release was timed to coincide with the 90th anniversary of the premiere of Berlin: Symphony of a City. City symphonies tend to be associated with the 1920s, when the genre originated and its most famous exemplars, Berlin and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, were made. The genre has never disappeared, but Barrett has written that he chose “to make the film in a style associated with the filmmakers of the 1920s.”

For me, it captures well the style of the 1920s, and particularly Berlin. Shot in black-and-white, London Symphony falls into four movements, following a day in the life of the city–with, as in Berlin, pauses for lunch and dinner particularly dwelt upon. The opening section concentrates on buildings, and there are the inevitable juxtapositions of old and new (see bottom). Multiple cinematographers filmed the footage, but their work blends into a unified visual whole with many striking compositions.

Ruttmann injects occasional implicit political commentary, as when he juxtaposes shots of beggars in the streets with the well-fed Berliners in restaurants. Barratt concentrates on the beautiful and peaceful side of London–historic buildings, quiet parks, pleasant markets, and river scenes. The rather grubby and crowded atmosphere of, say, the West End of London is nowhere to be seen, which befits “a love letter.”

In January The Indomitable Teddy Roosevelt joined the MOD catalog. This is a reissue of a 1983 television documentary that mixes documentary footage (Roosevelt was the first president to be filmed) and staged scenes.

Edition Filmmuseum

This series continues its steady release of experimental filmmaker James Benning’s works with a sixth two-disc set (DVD only) that goes back to his earliest features, films that solidified his international reputation. The new two-disc set contains two films from the late 1970s, 11 x 14 (1977) and One Way Boogie Woogie (1978). Jim followed up the latter, a series of sixty shots of Milwaukee cityscapes, with 27 Years Later (2005), which presents the same series of locations, and One Way Boogie Woogie 2012, which further documents the changes in the filmmaker’s hometown. All three films are included in this set.

11 x 14 flirts with presenting a narrative without ever really concentrating on it. We see some of the same people at intervals, but no causal events link them, and their actions create situations rather than developing stories. Instead, the film’s shots, some quite lengthy, others brief, explore the urban and rural landscapes of Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural roads and fields in the surrounding area. (A familiar highway sign pointing the way to Madison is glimpsed at one point.)

For the most part the urban images concentrate on run-down areas, with motifs of travel (billboards, airplanes) and drinking (bars and more billboards) hinting at contrasting modes of escape. The shot above captures both motifs at once.

Given that Jim’s films seldom play outside festivals and museum venues, the Filmmuseum series is vital–though many of the images in these films are long or even extreme long-shots and benefit from being seen on a big screen. The last time we had a chance to do so was when RR (2007) was shown at the 2008 Vancouver International Film Festival. The Austrian Filmmuseum also published a book on Jim’s work, which David discusses here.

London Symphony (2017)

Posted in Directors: Benning, Experimental film, Film comments, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, National cinemas: Germany, National cinemas: UK, Silent film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Catching up with the past: Recent DVD and Blu-ray releases open printable version

| Comments Off on Catching up with the past: Recent DVD and Blu-ray releases

Monday | July 9, 2018

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Jeff here:

Last week, the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art” videos dropped on FilmStruck. The topic this time was continuity editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Many of our faithful blog readers are surely familiar with the techniques and devices that make up the continuity system. The video is really intended to be a primer for the uninitiated. It illustrates some of the basic formal elements of classical continuity, such as the eyeline match, shot/reverse shot, and the 180° rule.

In the video, I tried to highlight some of the reasons why the continuity system became common among popular cinemas around the globe. The tacit principles of the continuity system help ensure that:

- the story’s dimensions of space and time are clearly communicated to the audience

- characters’ and objects’ positions remain relatively constant from shot to shot

- that eyelines and screen direction stay consistent

- the spectator’s attention is guided to the most salient details in a scene.

The last may be the most important, if least understood. Several perceptual psychologists argue that one of the things that makes cinema a unique art form is its ability to produce attentional synchrony among viewers.

Editing is not the only means of guiding attention, to be sure. Filmmakers use lighting, composition, figure movement, camera movement, and blocking to nudge us to look at particular areas of the frame. The continuity system, though, further harnesses these shifts of attention by yoking them to the timing of cuts. Cuts are often coordinated with natural attention cues in a scene, such as conversational turns, changes in where the characters look, and pointing gestures. As Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting put it, “By piggy-backing on natural visual cognition, Hollywood style presents a highly artificial sequence of viewpoints in a way that is easy to comprehend, does not require specific cognitive skills, and may even be perceived by viewers who have never watched film before.”

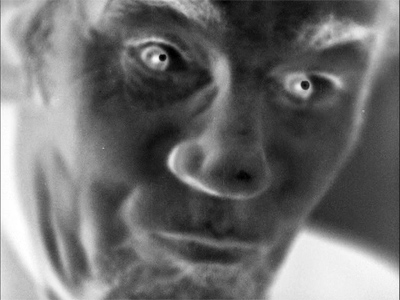

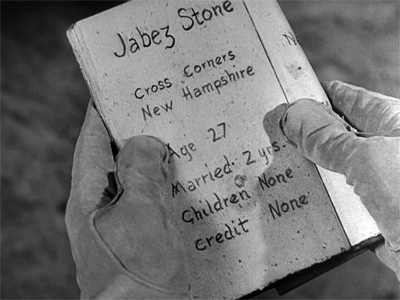

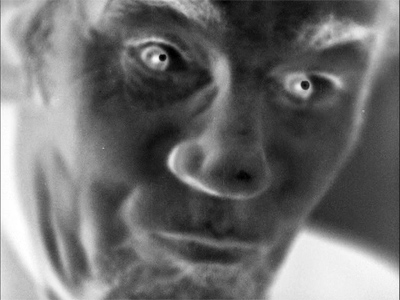

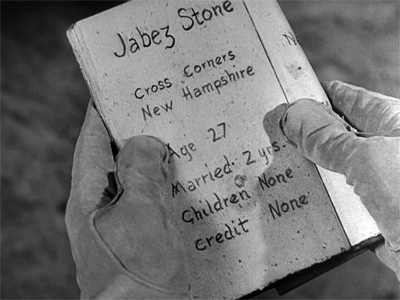

In its deployment of classical Hollywood editing techniques, The Devil and Daniel Webster doesn’t do anything particularly special. Rather, in telling the story of how a New Hampshire farmer, Jabez Stone, sold his soul to the devil, it beautifully illustrates the clarity and efficiency of Hollywood craft at the height of the studio era. Indeed, the editing epitomizes the style of director William Dieterle as a whole: simple, direct, no fuss, no muss.

That being said, The Devil and Daniel Webster does add a few wrinkles to the usual Hollywood style. For example, it uses “trick film” techniques dating back to the era of George Melies to highlight the magical powers of the diabolical Mr. Scratch.

When Jabez throws an axe, it is initially seen as a blur heading straight for Scratch’s head.

A combination of stop-motion substitution and rear projection shows the axe freeze in midair.

A traveling matte is then used as the axe bursts into flames.

Moreover, the Criterion DVD contains deleted scenes from an earlier preview version of the film titled Here is a Man. This alternate version was, in fact, more formally adventurous than the one commonly seen by contemporary audiences. Each time something bad befalls Jabez during the first 20 minutes of the film, Here is a Man cuts to a few frames of photographic negative of Scratch. For instance, when Mary accidentally falls off a wagon, Dieterle cuts to Walter Huston smugly pursing his lips.

Dieterle and his collaborators wisely removed these shots from the final version of the film. The opening scene shows Scratch with Jabez’s name in a small book he carries with him.

When ruinous things start happening to Jabez, viewers naturally infer that Scratch caused them. The oddball moments in Here is a Man, unlike the other effects shots, don’t really add any new information and are heavy-handed in their symbolism.

The Long and the Short of It: Adapting Stephen Vincent Benét to the Silver Screen

Beyond offering good examples of editing craft, The Devil and Daniel Webster is of interest today for other reasons. One involves some of the creative choices made by Stephen Vincent Benét and Dan Totheroh in adapting the former’s short story, first published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1936. The second issue I’ll explore has to do with the way the film speaks to political issues of its moment. It seems endorse a collectivist vision of society as a counter to the excesses of unrestrained capitalism.

Most film adaptations use books for their source material, and most screenwriters face the challenge of condensing the book’s narrative to fit the running time of a typical feature film (roughly about two hours). In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, Benét and Totheroh faced the opposite problem.“The Devil and Daniel Webster” runs less than twenty pages in a Hythloday Press collection of Benét’s short stories. So how do you stretch Benét’s relatively slim tale to fit a 107 minute running time? Benét and Totheroh did what most screenwriters do when they confront the same dilemma. They add incidents, invent new characters, and develop new subplots, adding this material to the existing story spine.

Some print editions of Benét’s story break it into five parts with each new segment introduced with a Roman numeral. Part I introduces Daniel Webster via the tall tales told about him in the New England area. It also provides exposition to Jabez’s blighted existence, and the deal he makes with the devil. After breaking his plow on a stone, Jabez angrily proclaims, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil. And I would, too, for two cents!”

Part II covers the seven-year period of prosperity Jabez enjoys as well as his interest in contesting the mortgage held by the mysterious stranger. This section also establishes the stranger’s mystical powers as Jabez hears the voice of his neighbor, Miser Stevens, coming from a moth-like creature that the stranger captures in a bandanna.

Part III describes Jabez’s recruitment of Daniel Webster for his defense and the preparations for trial. Parts IV and V depict the trial itself. The former introduces the judge and jury, and portrays Daniel’s passionate defense of Jabez. The latter tells of the jury’s verdict and Daniel’s banishment of Mr. Scratch from New Hampshire.

One of the most striking things about Benét’s original story is how much of it focuses on the trial itself. Approximately half of the story covers Webster’s initial deliberations with Mr. Scratch, his demand for a trial, and the legal proceedings. In contrast, these story events account for less twenty percent of the film’s running time.

In expanding the story to feature length, Benét and Totheroh add new incidents, characters, and subplots to the early and middle sections of the screenplay. Consider, for example, Benét’s economy in his prose description of Jabez’s misfortunes:

If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them. If stones cropped up in his neighbor’s field, boulders boiled up in his; if he had a horse with the spavins, he’d trade it for one with the staggers and give something extra.

Years of toil and trouble for Jabez are compressed into three sentences. When Jabez breaks his plowshare, it becomes simply the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, coming at a time when his wife and children are sick and even his horse has a rheumy cough.

In their script, Benét and Totheroh create a handful of new vignettes to illustrate Jabez’s rotten luck. In the film’s first scene, Jabez’s pig breaks its leg after being chased by the family dog. Later, Jabez’s wife, Mary, takes a tumble off their wagon when trying to stop her husband from selling the family’s calf. Still later, a fox gets into Jabez’s henhouse. In the film, Jabez’s breaking point comes not with the plow, but after he spills precious seed in a puddle just outside his barn. Unlike the story’s description of blight and corn borers, these brief episodes not only visualize Jabez’s tribulations, but also contain their own short dramatic arcs.

Another way Benét and Totheroh expand the original story is to add depth and specificity to its secondary characters. In the original, Miser Stevens never appears as anything more than an insect that’s escaped from Scratch’s collecting box. In the film, he is much more fully fleshed-out character, especially as embodied by the wonderful character actor, John Qualen.

Benét and Totheroh’s screenplay uses Stevens to create important story parallels. Like Scratch, who possesses a mortgage on Jabez’s soul, Stevens holds the mortgage to the Stone farm. Yet, Stevens also has made a Faustian bargain with Mr. Scratch. His death at Jabez’s party lingers over the rest of the film, a vivid reminder of what’s at stake during the trial.

Benét’s story also treats Jabez’s wife and children quite impersonally. The characters are never named. The references to them mostly add narrative weight to Jabez’s sense of burden. In contrast, the film version not only give these characters names and individual traits, but also uses them to highlight changes Jabez undergoes once he becomes a wealthy landowner. Jabez and his wife, Mary, frequently argue about disciplining their son, Daniel. Jabez indulges Daniel, spoiling him but offering little in the way of love. Similarly, after becoming successful, Jabez also falls short of what we’d expect of a caring husband.

In the middle parts of the film, Jabez becomes crueler and harder. He starts treating trespassers on his land more harshly. He even fires a weapon at one in an effort to scare him away. His anti-social attitudes make him an outcast among the citizenry of Cross Corners.

As was the case with Jabez’s family, the film gives the townspeople more life and personality. Early on, they serve to motivate Daniel Webster’s presence in the story, welcoming him to Cross Corners and serving as a receptive audience for the Senator’s political views. Later, the townspeople act as a foil for Jabez, establishing an important thematic contrast between his laissez faire mindset and their more communitarian values.

Lastly, Benét and Totheroh also invent several new characters for the film adaptation. Of these, the most important is Belle. Loosely allied with Mr. Scratch, Belle is ostensibly Daniel’s nanny, but is implied to be Jabez’s mistress. Belle supplies a sexual temptation not present in the original story, and this complements the temptations of wealth and power. In this respect, the character anticipates the femme fatales found in the cycle of films noir that appear later in the forties, especially as played by Simone Simon at her most fetching.

Although Dieterle was best known for costume pictures rather than film noir, the photographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster sometimes displays the kind of dark, moody look we associate with noir’s Germanic influence. Consider, for example, the shot of Scratch’s entrance into Jabez’s barn. The mists, the backllight, and the gnarled tree in the background all foreshadow the darkness that will soon take hold of Jabez’s soul.