Monday | July 9, 2018

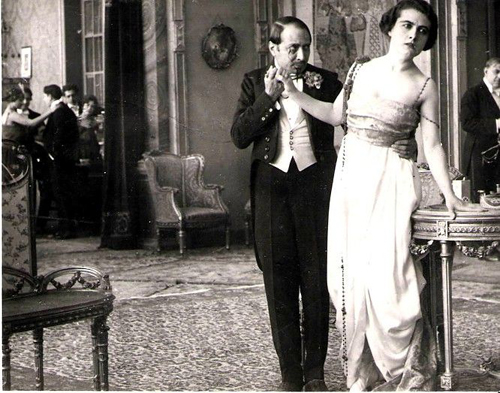

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Jeff here:

Last week, the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art” videos dropped on FilmStruck. The topic this time was continuity editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Many of our faithful blog readers are surely familiar with the techniques and devices that make up the continuity system. The video is really intended to be a primer for the uninitiated. It illustrates some of the basic formal elements of classical continuity, such as the eyeline match, shot/reverse shot, and the 180° rule.

In the video, I tried to highlight some of the reasons why the continuity system became common among popular cinemas around the globe. The tacit principles of the continuity system help ensure that:

- the story’s dimensions of space and time are clearly communicated to the audience

- characters’ and objects’ positions remain relatively constant from shot to shot

- that eyelines and screen direction stay consistent

- the spectator’s attention is guided to the most salient details in a scene.

The last may be the most important, if least understood. Several perceptual psychologists argue that one of the things that makes cinema a unique art form is its ability to produce attentional synchrony among viewers.

Editing is not the only means of guiding attention, to be sure. Filmmakers use lighting, composition, figure movement, camera movement, and blocking to nudge us to look at particular areas of the frame. The continuity system, though, further harnesses these shifts of attention by yoking them to the timing of cuts. Cuts are often coordinated with natural attention cues in a scene, such as conversational turns, changes in where the characters look, and pointing gestures. As Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting put it, “By piggy-backing on natural visual cognition, Hollywood style presents a highly artificial sequence of viewpoints in a way that is easy to comprehend, does not require specific cognitive skills, and may even be perceived by viewers who have never watched film before.”

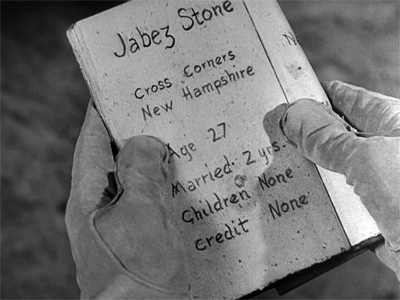

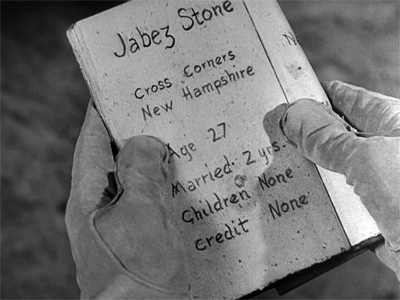

In its deployment of classical Hollywood editing techniques, The Devil and Daniel Webster doesn’t do anything particularly special. Rather, in telling the story of how a New Hampshire farmer, Jabez Stone, sold his soul to the devil, it beautifully illustrates the clarity and efficiency of Hollywood craft at the height of the studio era. Indeed, the editing epitomizes the style of director William Dieterle as a whole: simple, direct, no fuss, no muss.

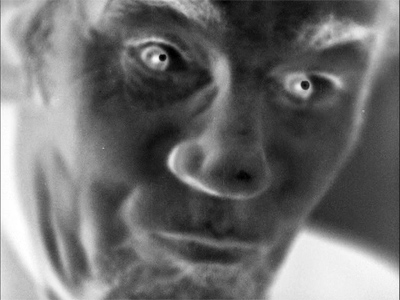

That being said, The Devil and Daniel Webster does add a few wrinkles to the usual Hollywood style. For example, it uses “trick film” techniques dating back to the era of George Melies to highlight the magical powers of the diabolical Mr. Scratch.

When Jabez throws an axe, it is initially seen as a blur heading straight for Scratch’s head.

A combination of stop-motion substitution and rear projection shows the axe freeze in midair.

A traveling matte is then used as the axe bursts into flames.

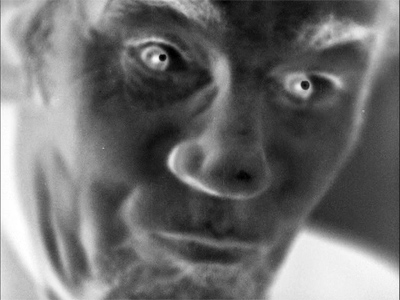

Moreover, the Criterion DVD contains deleted scenes from an earlier preview version of the film titled Here is a Man. This alternate version was, in fact, more formally adventurous than the one commonly seen by contemporary audiences. Each time something bad befalls Jabez during the first 20 minutes of the film, Here is a Man cuts to a few frames of photographic negative of Scratch. For instance, when Mary accidentally falls off a wagon, Dieterle cuts to Walter Huston smugly pursing his lips.

Dieterle and his collaborators wisely removed these shots from the final version of the film. The opening scene shows Scratch with Jabez’s name in a small book he carries with him.

When ruinous things start happening to Jabez, viewers naturally infer that Scratch caused them. The oddball moments in Here is a Man, unlike the other effects shots, don’t really add any new information and are heavy-handed in their symbolism.

The Long and the Short of It: Adapting Stephen Vincent Benét to the Silver Screen

Beyond offering good examples of editing craft, The Devil and Daniel Webster is of interest today for other reasons. One involves some of the creative choices made by Stephen Vincent Benét and Dan Totheroh in adapting the former’s short story, first published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1936. The second issue I’ll explore has to do with the way the film speaks to political issues of its moment. It seems endorse a collectivist vision of society as a counter to the excesses of unrestrained capitalism.

Most film adaptations use books for their source material, and most screenwriters face the challenge of condensing the book’s narrative to fit the running time of a typical feature film (roughly about two hours). In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, Benét and Totheroh faced the opposite problem.“The Devil and Daniel Webster” runs less than twenty pages in a Hythloday Press collection of Benét’s short stories. So how do you stretch Benét’s relatively slim tale to fit a 107 minute running time? Benét and Totheroh did what most screenwriters do when they confront the same dilemma. They add incidents, invent new characters, and develop new subplots, adding this material to the existing story spine.

Some print editions of Benét’s story break it into five parts with each new segment introduced with a Roman numeral. Part I introduces Daniel Webster via the tall tales told about him in the New England area. It also provides exposition to Jabez’s blighted existence, and the deal he makes with the devil. After breaking his plow on a stone, Jabez angrily proclaims, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil. And I would, too, for two cents!”

Part II covers the seven-year period of prosperity Jabez enjoys as well as his interest in contesting the mortgage held by the mysterious stranger. This section also establishes the stranger’s mystical powers as Jabez hears the voice of his neighbor, Miser Stevens, coming from a moth-like creature that the stranger captures in a bandanna.

Part III describes Jabez’s recruitment of Daniel Webster for his defense and the preparations for trial. Parts IV and V depict the trial itself. The former introduces the judge and jury, and portrays Daniel’s passionate defense of Jabez. The latter tells of the jury’s verdict and Daniel’s banishment of Mr. Scratch from New Hampshire.

One of the most striking things about Benét’s original story is how much of it focuses on the trial itself. Approximately half of the story covers Webster’s initial deliberations with Mr. Scratch, his demand for a trial, and the legal proceedings. In contrast, these story events account for less twenty percent of the film’s running time.

In expanding the story to feature length, Benét and Totheroh add new incidents, characters, and subplots to the early and middle sections of the screenplay. Consider, for example, Benét’s economy in his prose description of Jabez’s misfortunes:

If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them. If stones cropped up in his neighbor’s field, boulders boiled up in his; if he had a horse with the spavins, he’d trade it for one with the staggers and give something extra.

Years of toil and trouble for Jabez are compressed into three sentences. When Jabez breaks his plowshare, it becomes simply the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, coming at a time when his wife and children are sick and even his horse has a rheumy cough.

In their script, Benét and Totheroh create a handful of new vignettes to illustrate Jabez’s rotten luck. In the film’s first scene, Jabez’s pig breaks its leg after being chased by the family dog. Later, Jabez’s wife, Mary, takes a tumble off their wagon when trying to stop her husband from selling the family’s calf. Still later, a fox gets into Jabez’s henhouse. In the film, Jabez’s breaking point comes not with the plow, but after he spills precious seed in a puddle just outside his barn. Unlike the story’s description of blight and corn borers, these brief episodes not only visualize Jabez’s tribulations, but also contain their own short dramatic arcs.

Another way Benét and Totheroh expand the original story is to add depth and specificity to its secondary characters. In the original, Miser Stevens never appears as anything more than an insect that’s escaped from Scratch’s collecting box. In the film, he is much more fully fleshed-out character, especially as embodied by the wonderful character actor, John Qualen.

Benét and Totheroh’s screenplay uses Stevens to create important story parallels. Like Scratch, who possesses a mortgage on Jabez’s soul, Stevens holds the mortgage to the Stone farm. Yet, Stevens also has made a Faustian bargain with Mr. Scratch. His death at Jabez’s party lingers over the rest of the film, a vivid reminder of what’s at stake during the trial.

Benét’s story also treats Jabez’s wife and children quite impersonally. The characters are never named. The references to them mostly add narrative weight to Jabez’s sense of burden. In contrast, the film version not only give these characters names and individual traits, but also uses them to highlight changes Jabez undergoes once he becomes a wealthy landowner. Jabez and his wife, Mary, frequently argue about disciplining their son, Daniel. Jabez indulges Daniel, spoiling him but offering little in the way of love. Similarly, after becoming successful, Jabez also falls short of what we’d expect of a caring husband.

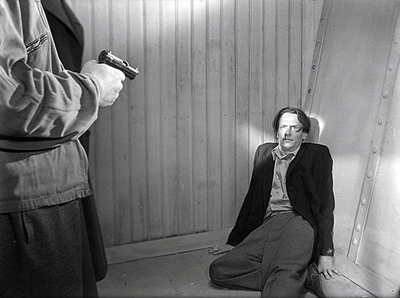

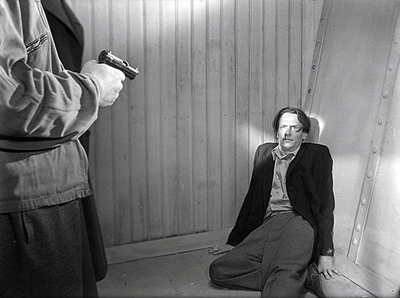

In the middle parts of the film, Jabez becomes crueler and harder. He starts treating trespassers on his land more harshly. He even fires a weapon at one in an effort to scare him away. His anti-social attitudes make him an outcast among the citizenry of Cross Corners.

As was the case with Jabez’s family, the film gives the townspeople more life and personality. Early on, they serve to motivate Daniel Webster’s presence in the story, welcoming him to Cross Corners and serving as a receptive audience for the Senator’s political views. Later, the townspeople act as a foil for Jabez, establishing an important thematic contrast between his laissez faire mindset and their more communitarian values.

Lastly, Benét and Totheroh also invent several new characters for the film adaptation. Of these, the most important is Belle. Loosely allied with Mr. Scratch, Belle is ostensibly Daniel’s nanny, but is implied to be Jabez’s mistress. Belle supplies a sexual temptation not present in the original story, and this complements the temptations of wealth and power. In this respect, the character anticipates the femme fatales found in the cycle of films noir that appear later in the forties, especially as played by Simone Simon at her most fetching.

Although Dieterle was best known for costume pictures rather than film noir, the photographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster sometimes displays the kind of dark, moody look we associate with noir’s Germanic influence. Consider, for example, the shot of Scratch’s entrance into Jabez’s barn. The mists, the backllight, and the gnarled tree in the background all foreshadow the darkness that will soon take hold of Jabez’s soul.

In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, tracing the film’s lineage back to German expressionism is fairly easy. Prior to becoming a director, Dieterle was an actor in dozens of German silent films, including F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). Murnau’s adaptation of Goethe’s play not only shares its narrative conceit with Dieterle’s film, but is also one of the most strikingly photographed of his twenties masterpieces.

Looking both backward and forward, The Devil and Daniel Webster might seem like a link between German Expressionism and American film noir. Like German films of the 1910s and 1920s, Dieterle’s film contains some of the fantasy elements found in canonical titles like The Student of Prague (1913), Der Golem (1915), or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Dieterle’s curious afterlife fantasy Six Hours to Live (1932), discussed in an earlier entry, has a strong affinity with Gothic and Expressionist imagery. Like films noir of the forties, the cinematographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster captures the story’s dark, fatalistic tone.

Indeed, the look of the final trial scene displays the same sort of stylization seen in the dream sequence of The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a film often seen as a key noir progenitor.

Still, Dieterle also retains the folksy Americana that was an appealing part of Benét’s original story. Some of the characters, like Ma Stone or Squire Slossum, seem like they’ve wandered into the story from one of Frank Capra’s small towns or John Ford’s rural comedies. This combination makes The Devil and Daniel Webster a true original. Indeed, it might count as an almost singular example of “cracker barrel noir” if the term itself didn’t seem like a complete oxymoron.

Things That Make a Country a Country, and a Man a Man: Benét’s Tale as Allegory

One of the other things that interests me about The Devil and Daniel Webster is the degree to which both the story and the film can be read as allegory. Benét’s original narrative certainly makes American identity a central theme. The opening paragraph proposes that, if you go to Daniel Webster’s gravesite and call his name, you’ll hear his deep, rolling voice ask, “Neighbor, how stands the Union?” Benét adds, “Then you better answer the Union stands as she stood, rock-bottomed and coppersheathed, one and indivisible, or he’s liable to rear right out of the ground.” This description not only foreshadows the oratorical power that Webster will display when Jabez goes on trial, but also the sacrifices Scratch prophesies. These include Webster’s loss of two sons in combat and a missed opportunity to become president.

Later, Webster will challenge Scratch on the grounds of his nationality, saying “no American citizen may be forced into the service of a foreign prince.” Scratch responds that he is an American, and further that he was present for “the first wrong done to the first Indian” and when the first American slave ship set sail for the Congo. Moreover, when Scratch assembles his jury, he selects a group of black-hearted souls whose dark deeds affected the course of the nation’s history. Among them is the pirate Edward Teach, otherwise known as Blackbeard. There’s also Walter Butler, the architect of the Cherry Valley massacre; Simon Girty, who burnt men at the stake; and Governor Thomas Dale, who Benét claims “broke men on the wheel.” Overseeing the proceedings is Judge John Hathorne, a magistrate in Salem who supervised some of the witch trials.

The larger significance of these passages is hard to ignore. Jabez may be on trial within the narrative, but Benét seems to put America itself on trial. The plaintiff and defendant, thus, come to symbolize the yin and yang of America’s soul. Webster represents the virtues that define the American ethos: grit, pluck, ingenuity, and liberty. Scratch, on the other hand, associates himself with the nation’s original sins: genocide, slavery, cruelty, torture, and theocratic inquisition. Webster emerges victorious in the legal battle, but as he says in his summation, our citizens’ hard-won freedom came at a cost of suffering and tribulation. Successes and failures are all part of the great journey of humanity. Says Webster, “And everybody had played a part in it, even the traitors.”

Dieterle’s film preserves all of these elements of Benét’s short story, but adds a couple of wrinkles of its own. First, General Benedict Arnold is added to the film’s panel of jurors, even though he is pointedly absent from the original. In the story, Webster observes that he misses Arnold’s company and is told that the General is engaged in other business. Benedict Arnold is not only fully present in the film version, but is even featured prominently during the trial scene in several medium close-ups.

Webster even singles out Arnold in his impassioned defense of Jabez’s character. Using Arnold’s betrayal of his country as a cautionary tale, the orator asks the jury to give Jabez the second chance that the devil denied to them.

The other, even more important, change made by Benét and Totheroh is the subplot concerned with the formation of the Grange. Officially known as the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, the Grange was founded in 1867 to promote the interests of farmers and rural communities. But Webster died in 1852. As an addition to the screenplay of The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Grange seems to be a historical anomaly.

So why this anachronistic subplot? The simple answer is that it sharpens the conflict between Jabez and the other townspeople. Not only is he differentiated in class, but he’s set apart by his personal values. The less obvious answer involves the film’s historical context. Released in 1941, the story of a lone holdout resisting the pressure of others in his community likely would evoke broader geopolitical issues. The plea for unity in the face of existential evil would seem to suggest The Devil and Daniel Webster works as an allegorical critique of American isolationism on the threshold of World War II.

Like other allegories, this type of reading follows a pattern of metaphorical substitution. The Grange becomes a stand-in for the Allied Powers. Scratch represents Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo, and other Axis leaders. And, as discussed above, Stone and Webster symbolize America itself.

Dieterle’s earlier career in Hollywood also offers some additional warrant for this interpretation. He was a German Jew who emigrated to the U.S. in 1930. His relocation was less about fleeing the Nazis than it was the opportunity to work for Warner Bros. Still, Dieterle bore witness to the corrosive effects of Nazi ideology, and his directorial assignments show a loose affiliation with anti-Fascist politics. He helmed The Life of Emile Zola, a Warners biopic that depicts the French author’s involvement in the Dreyfus affair. The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1938. Thanks to its timely exploration of anti-Semitism, Zola burnished Warner Bros. reputation as Hollywood’s most socially conscious studio.

That same year, Dieterle directed Blockade (1938) for producer Walter Wanger. Although it is mostly a routine espionage thriller, the film is now remembered as one of the few films Hollywood made about the Spanish civil war. As scripted by John Howard Lawson, who later was blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten, Blockade is now seen as an emblem of the Popular Front. Most film historians associate it with anti-Fascist politics, even though the film pointedly avoids identifying the Loyalist and Nationalist sides of the conflict.

Unlike these previous projects, The Devil and Daniel Webster positioned Dieterle as both producer and director. The creative decisions involved in the addition of the Grange subplot would seem more directly under his control. The film’s thematic emphasis on collective interests seems to suggest this political subtext in much the same way that Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) is sometimes viewed as a parable of democracy’s failure in the face of dictatorship.

In highlighting this allegorical dimension of The Devil and Daniel Webster, I don’t wish to suggest that it makes the film inherently more interesting. Indeed, like other allegorical interpretations, it seems a bit reductive and simplistic. More importantly, if taken too far, these types of interpretive strategies quickly become wrongheaded and even silly (i.e. Belle as a stand-in for Vichy collaboration).

Yet, I also can’t help but feel that The Devil and Daniel Webster’s invocation of American identity offers something important to a contemporary audience. If, like me, you bristle every time you hear “American interests” referenced as the reason to abandon the Paris Accords or to potentially withdraw from NATO, then you have a sense of the film’s relevance to our moment.

The whole arc of the Grange subplot seems to invert much contemporary political rhetoric insofar as it dramatizes the social benefits of the Commons and the individual tragedy of self-interest. In the parlance of our times, Jabez is a risk-taker, mortgaging his immortal soul for the promise of earthly riches. Yet, when we see the resulting inequality in Dieterle’s film, we recognize the situation for what it is. For Jabez, Miser Stevens, and other capitalist mountebanks, it is, quite literally, a deal with the devil. And that, consarn it, is a lesson that all modern viewers can take to heart.

A handy introduction to the continuity system can be found in Chapter 6 of Film Art.

To learn more about the role of editing in guiding viewers’ attention, see Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting, “A Window on Reality: Perceiving Edited Moving Images,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21, no. 2 (2012): 107-113. A PDF of this essay can be found here.

Stephen Vincent Benét can be found in many places around the web, including here. Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (1974, University of California Press) remains a useful introduction to the movement’s lighting and visual motifs. For more on the interpretation of films as political allegories, see my book Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds (2014, University of California Press).

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Film technique: Editing, FilmStruck, Hollywood: Artistic traditions |  open printable version

| Comments Off on FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL: A guest post by Jeff Smith open printable version

| Comments Off on FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Tuesday | July 3, 2018

Lucky to Be a Woman (1955).

DB here:

How to sum up nine days of Cinema Ritrovato? I logged thirty-two features and half as many shorts and fragments, along with a few panels and workshops. Fate cursed me with the need to blog and to sleep, so I missed many prime items. And that’s including my (sad) decision not to revisit films I’d already seen, so I sacrificed new exposure to masterpieces from Ozu, Mizoguchi, Feuillade, Leone, de Sica, etc.

In this last Bologna roundup, all I can do is wave at some of the surprises and discoveries that captivated me.

Many of my pals praised the Mexican noir Western Rosauro Castro (1950), which I had to miss, but I did get compensated by Prisioneros de la Tierra (1939), an Argentine classic of romantic realism. The plot concerns the exploitation of peasant migrants forced to work in dire conditions. One scene, of a drunken doctor in the throes of the DTs, got a rise out of Jorge Luis Borges.

Even more shocking was the red-light melodrama Víctimas del Pecado (1951, above) by the great Emilio Fernández. A newborn baby dumped into a garbage can; a preening, sadistic pimp who can smoke, chew gum, and dance frantically at the same time; a nightclub dancer who tries to live righteously but winds up in prison for her pains; and several splashy music numbers–who could resist this? Not the Bologna audience, who burst into applause when, after slapping a child silly, said pimp got a quick and violent comeuppance. Of course the gorgeous cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa contributed a lot: One shot of a train blasting black smoke into the night would be enough to exalt a far less delirious movie.

Thanks to Dave Kehr of MoMA, who brought a sampler from his recent Fox retrospective, and to UCLA and other sources, aficionados of American studio cinema had no shortage of delights. Monta Bell’s Lights of Old Broadway (1925) gave Marion Davies a dual role as twins separated at birth and she made the most of half of it, playing a no-nonsense colleen who makes it big at Tony Pastor’s. Part of the fun was the film’s historical references: Teddy Roosevelt as an undisciplined schoolboy, Weber & Fields as a kiddie act, and a solicitous Thomas Edison urging the heroine to invest in electricity.

Ten years later, One More Spring (1935, above) from Henry King offered a gentle seriocomic Depression tale. Two homeless men squatting in a garage take in a woman who sleeps on the subway, and they try to make ends meet with the help of a kindly old couple. At first engagingly episodic in the McCarey manner, the plot gets more tightly bound when the old couple faces the loss of their savings. Janet Gaynor is endearing, as usual, and Warner Baxter brings his clipped energy to the role of a hopelessly optimistic failure. There are no villains. The banker struggles to save his depositors, though he’s frank enough to admit, “It’s all the fault of the Republicans. Still, I’ll vote for them in the next election. With the Democrats you never know what to expect.” Another big laugh from the crowd around me.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels. That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

Another 1940s technique was the chaptered or block-constructed film, Holy Matrimony (1943), a genial comedy about switched identities, contains sections with titles like “But in 1907” and “And so in 1908.” The film, about a painter brought back to London from his tropical hideaway, reworks the Gauguin motif made famous by Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence (1919). Was this release an effort to build on Albert Lewin’s 1942 version of the novel? Monty Woolley plays himself, but Gracie Fields brought real warmth to the clever, ever practical woman who marries him.

Holy Matrimony was a welcome, if minor entry in the John Stahl retrospective. I had to miss the much-praised When Tomorrow Comes (1939) but was happy to break my rule of avoiding things I’d seen before when I had a chance to revisit Imitation of Life (1934). I persist in thinking this better than the Sirk version, not least because of its harder edge. Beatrice Pullman’s exploitation of her servant Delilah’s pancake recipe carries a sharp economic bite, and the brutal classroom scene yanks our emotions in many directions. (While Peola writhes in her seat, her mother asks innocently, “Has she been passin’?”) As in Stahl’s other 1930s efforts, his studiously neutral style is built out of profiled two shots in exceptionally long takes.

Ritrovato has always done well by its diva films, under the curatorship of Marianne Lewinsky. (They’ve just released a hot-pink box set of four classics.) In tribute to 1918 there were several star vehicles. I’ve already mentioned L’Avarazia (1918), an installment in a Francesca Bertini series devoted to the seven deadly sins.

Another high point was La Moglie di Claudio (1918), an exemplary tale of excess. When a movie starts by comparing its heroine to a spider, you know she means trouble. Cesarina (Pina Minichelli) two-times her husband, has an illegitimate child, flirts relentlessly with her husband’s protégé, collaborates with spies, and steals the plans to the cannon the husband has designed. She does it all in high style. As she dies, she falls clutching a window curtain.

In a fragment from Tosca (1918), we got a quick lesson in the illogical powers of cinematic composition. Tosca (Bertini again) visits her lover Mario in prison. Their furtive conversation is played out while the shadows of the guards come and go in the background. That’s a source of some suspense for us.

And for the couple as well. Instead of looking left at the offscreen window itself, which they could easily see, they–like us–turn to monitor the silhouettes.

It’s a nice variant on the background door or window so common in 1910s film.

Of all the surprises, the biggest for me was This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension, 1950), an Ingmar Bergman thriller. You read that right.

This Cold War intrigue shows spies from Liquidatsia (you read that right too) infiltrating a circle of refugees living in Sweden. The first half hour is soaked in noir aesthetics, with men in trenchcoats glimpsed in bursts of single-source lighting. The preposterous plot gives us a briefcase full of secret papers, attempted murder by hypodermic, torture scenes, and enemy agents acting impossibly suave at gunpoint. A cadre meets in a movie theatre playing a Disney cartoon, with Goofy’s offscreen gurgles punctuating an informer’s confession.

Bergman forbade screenings of the film, but Bologna was given the rare chance to reveal another side of his obsessions with brooding solitude and the pitfalls of love. Peter von Bagh’s illuminating essay included in the catalogue rightly emphasizes how in This Can’t Happen Here murder becomes the natural outcome of an unhappy marriage.

My visit was topped off by the charming Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) in the Mastroianni strand. Sophia Loren, looking like a million and a half bucks, plays a working girl accidentally turned into tabloid cheescake. Mastroianni is a louche photographer who can make her career. Bantering at breakneck speed, they thrust and parry for ninety-five minutes, all the while satirizing modeling, moviemaking, and the itchy palms of philandering middle-aged men. Mastroianni spins minutes of byplay out of an unlit cigarette, while La Loren plants herself like a statue in the foreground, facing us; if Marcello’s lucky, she may address him with a smoldering sidelong glance.

What’s not to like? After thirty-two years, Ritrovato’s magnificence is unflagging.

As usual, thanks must go to the core Ritrovato team: Festival Coordinator Guy Borlée (with appreciation for help with this entry) and the Directors (below). They and their corps of workers make this vastly complex celebration of cinema look easy. It’s actually a kind of miracle.

Ehsan Khoshbakht, Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, and Gian Luca Farinelli.

Posted in 1910s cinema, 1940s Hollywood, Directors: Bergman, Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, National cinemas: Italy, National cinemas: Mexico, National cinemas: South America, Tableau staging |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Bye bye Bologna open printable version

| Comments Off on Bye bye Bologna

Saturday | June 30, 2018

The Woman under Oath (1919).

DB here:

Hard to keep up. Herewith, some highlights as Cinema Ritrovato, the Cannes of classic cinema, winds down.

Grease, still the word

Patricia Birch was a dancer with Martha Graham and Agnes De Mille. She went on to participate in West Side Story and to choreograph The Wild Party (1975) and both stage and film versions of A Little Night Music (1973, 1977). What brought her to Bologna was the restored version of Grease (1978). She choreographed that on both stage and screen, and she talked about it at a stimulating panel with Ehsan Khoshbakht and her son Peter Becker, of Criterion Films.

I had thought that Grease followed the vogue for boomer high-school nostalgia triggered by American Graffiti (1973), but it was actually ahead of that. The original Chicago version, reportedly raunchier than the New York version, premiered in 1971. It opened on Broadway in 1972 and ran until 1980. The film modified the stage show and added some songs.

Ms. Birch was a font of information about how she conceived the numbers. She says she thinks of dance as “timed behavior,” not set steps but patterns of motion. This idea allows her to choreograph actors who didn’t have dance training but who could “move well.” Peter ran a clip showing a passage of cascading hallway mischief that was as rhythmic as a dance number. This was one of several group-action scenes that Ms. Birch coordinated.

The Grease ensemble was huge, and Ms Birch organized it in a quasi-military way. There was a core of twenty proficient dancers, ten male-female couples. They supervised and coached the less skilled performers. For “We Go Together,” set in a carnival, each couple found business and steps for thirty other dancers.

“We Go Together” was the sort of big showstopper she called “Paramount numbers.” There were also the smaller-scaled “semi-Paramount numbers” and the intimate, character-driven “Internal numbers.” Ms Birch pointed out how the Paramounts built their power on unison steps and, eventually, massive kicklines. “People like to see the world in unison. Gets ’em every time.”

I learned a lot from Patricia Birch’s spirited discussion. Watch for a version of the panel to show up online.

Cutting edges

Film curator Olaf Müller set a new Ritrovato record: the shortest retrospective to date. Three films running less than twenty minutes introduced us to the oeuvre of Franz Schömbs.

Schömbs was a painter who became, according to Olaf, “probably the only avant-garde filmmaker of 1950s West Germany.” He started in the thirties by mounting paintings in rows, inviting viewers to walk along and sense the changes among them. After the war Schömbs tried to revive the experimentation of the Weimar period, principally through abstract films rich in color and design.

The films on the program were dense. Opuscula (1946-1952) consists of patches of color that slide to and fro “on top” of one another thanks to panning and tilting movements. The superimpositions create some striking visual hallucinations, as when blocks of white refuse to change color while other forms around them do. Die Geburt des Lichts (“The Birth of Light,” 1957, above), my favorite, transposes that constant movement to the patches of color themselves. These patches, as crisp as paper cutouts, have thrusting edges that keep slicing into the mates around them. Apparently Schömbs achieved the effect by applying paint to layers of glass and adjusting them frame by frame. Den Eisamen Allen (“To All the Lonely Ones,” 1962) uses what seemed to me traveling mattes, again enlivened by rich color.

Once more, Bologna proves a showcase for films that would otherwise go missing from film history.

Trial, with error

The courtroom drama was a mainstay of early twentieth-century theatre, but in 1915, playwright Elmer Rice gave it a twist. On Trial presented a murder trial by dramatizing the witnesses’ testimony in flashbacks. Rice offered another innovation as well: his flashbacks are non-chronological, starting with the most recent incident and reserving the climax for the earliest piece of action. Using the courtroom drama to play with time and viewpoint became a staple of American theatre and cinema.

Popular culture is a teeming mass of copies and near-copies–the switcheroo principle–so it didn’t take long for other storytellers to vary and complicate the trial format. One of the neatest examples was on display in Bologna. In the John Stahl silent drama The Woman under Oath (1919), flashbacks replay key actions according to what different witnesses know. We get no fewer than five flashbacks, some presenting incidents leading up to the crime, others recounting the murder itself. The later ones fill gaps in the earlier ones and culminate in a full, accurate version of the killing.

Proving once more that 1910s cinema can be pretty intricate, the same pieces of action get redeployed in different witnesses’ testimony. Sometimes the camera setups are varied to differentiate the versions.

At other moments, nearly identical framings mislead us by concealing important information. The young man accused of the murder is shown near the victim in three pieces of testimony, with the first two instances being essentially identical but the last presentation providing different information. (To avoid a spoiler, I don’t show the portion of the third shot that yields that information.)

The Woman under Oath shows a sophisticated understanding of how framing can conceal information without our being aware of it. And in retrospect what seems a colossal coincidence during the first presentation of the killing turns out to be a perfectly motivated key to the solution.

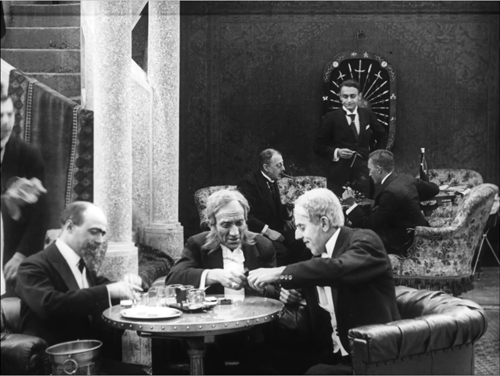

Switcheroos on the trial-testimony format showed up in other Ritrovato films. By 1928, the idea of conflicting testimony enacted in “lying” flashbacks was conventional enough to be parodied in René Clair’s Les Deux timides (“Two Timid Souls”). Here the disparities are wildly comic, accentuated by split-screen and freeze frame. Albert Valentin’s La Vie de Plaisir (1944), made under the German occupation of France, is an elegant social comedy pitting a couple against one another in divorce court. The spiteful witnesses offer testimony damning the husband only to get refuted in replays that reveal extra information. Throughout world cinema, the flashback trial film seems to have been one way oblique narrative strategies were made understandable for a wide audience.

Thanks as ever to Guy Borlée for assistance, and to the Ritrovato programmers for supplying so many treats. Thanks also to Kelley Conway for discussion of the courtroom movies. We should also be grateful to the BFI for providing Bologna with the copy of The Woman under Oath.

One rough precedent for Rice’s play is Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). The lingering awareness of Rice’s play is evident in Variety‘s review of The Woman under Oath, which the critic labeled “a sort of ‘On Trial’ affair” (20 June 1919, 52). In the same year there was an interesting parallel in the flashback testimony in Dreyer’s The President (1919).

You can find more about the switcheroo premise in my Reinventing Hollywood, which also discusses the trial format. For more on flashbacks see this entry. A series of entries on complex 1910s cinema start with this one.

P.S. 3 July 2018: Thanks to Peter Becker for a correction.

Les Deux timides (1928).

Posted in 1910s cinema, Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato, Film comments, Film genres, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Narrative strategies |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Edgy color, trial testimony, and the world in unison: More movies at Ritrovato open printable version

| Comments Off on Edgy color, trial testimony, and the world in unison: More movies at Ritrovato

Wednesday | June 27, 2018

I think this has become my favorite Ritrovato key image.

DB here:

Cinema Ritrovato rolls on, leaving your obedient servant little time to blog. Herewith some quick impressions on a thin slice of all that’s going on. For a full schedule of this incredible event, go here.

IB or not IB

“Not all IB Tech prints are created equal,” explained Academy Film Archivist (and UW–Madison grad) Mike Pogorzelski. In his last of his annual Technicolor Reference Print shows, he pointed out that Technicolor sent its best-balanced prints to big-city venues and circulated them widely. As a result, they got worn out. The prints most likely to survive were less-than-perfect ones sent to the hinterlands or just kept as backups. Hence the need to preserve the Reference Prints selected by the filmmakers as defining the Technicolor timbre of each film.

With clips ranging from The Godfather and Let It Be to Sssss and Billy Jack, the sample gave a good sense of what Tech looked like a few years before the imbibition (IB) process was abandoned in 1974. Mike and Emily Carman introduced the extracts with informative commentary. I had always thought that Gordon Willis’s cinematography on the Godfather films and The Parallax View increased graininess, and this show seemed to confirm that sense.

Those naughty pre-Code pictures, again

The John Stahl and William Fox retrospectives brought some spicy material. Women of All Nations (1931), Raoul Walsh’s episodic sequel to What Price Glory?, had Quirt and Flagg on the verge of all-out cussing in nearly every scene. A monkey wriggling inside El Brendel’s trousers created moments of good dirty fun. Bachelor’s Affairs (tee-hee, 1932) had Adolph Menjou peering down a golddigger’s front and praising her virtues: “What a charming combination.” She asks if it’s showing. Likewise this repartee: “Were you out last night?” “Not completely.”

William Dieterle’s Germanic Six Hours to Live (1932) begins as a political thriller and devolves into a Twilight Zone fantasy. A representative of a small country passionately protests worldwide tariff legislation. To keep his vote from vetoing the action, spies target him for elimination. Soon enough, he’s throttled to death. But an enterprising scientist takes the opportunity to try out his resuscitation ray, which gives the hero a few more hours to make his mark.

John Seitz photographed the whole farrago in glowing imagery shot through with shafts of blackness, alternately soft-focus and crisply edged. Here’s the magic machine.

The film’s look is an example, I suppose, of what Andrew Sarris once called “Foxphorescence”–the signature of a studio that, from Murnau and Borzage to Ford and 1940s noirs, played host to dazzling pictorial effects.

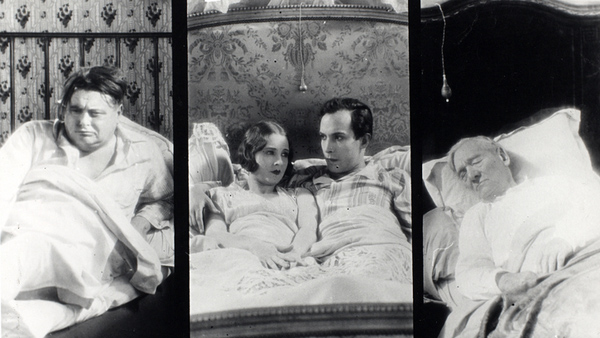

Not completely naughty, but certainly a film about sexual jealousy, was Seed (1931), one of the most anticipated films of the Stahl cycle. It lived up to its reputation as a masterly orchestration of sympathies. At the center is a love triangle based on two women’s roles: the mother and the businesswoman.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him. Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

As often happens in Hollywood, the plot works only if the man is a jerk, and the action will set up things to make the woman take the blame. Mildred may not have schemed to pull Bart away from the start, but the shift in our sympathy to Peggy is pretty decisive. The film’s patient pace and stringently objective presentation lets contrasting feelings get developed gradually. The kids, particularly the whining runt of the litter, are annoying and troublesome. Mildred is no obvious predator, Peggy is trying valiantly to accommodate Bart’s ambition, and he’s enjoying his vacation from fatherhood while still struggling, albeit weakly, to stay loyal to his family.

Stahl was one of the major long-take directors of 1930s Hollywood, and Seed is exemplary in this respect. (The average shot lasts about twenty seconds.) His back-to-basics two shots, facing off characters in profile, become the default setting; there are scarcely any reverse angles or eyeline matches. This apparently simple creative choice, anticipating Preminger’s method of the 1940s and 1950s, puts all characters on an equal footing. The framings force us to concentrate on their conversation, avoiding the customary cuts that punch up particular lines or reactions. A similar steady observation is at work in Stahl’s fine Imitation of Life (1934) and Magnificent Obsession (1936).

1918 and all that

L’avarizia (1918). Production still.

Regular readers of this blog know that one area of my research is the stylistics of 1910s cinema in various countries. (Check the category tableau staging for a sample.) Naturally I dropped obsessively in on the 100-years-ago strands at this year’s Bologna. While there are more films to come, I found plenty to enjoy and think about in the first few days.

There was, for instance, Der Fall Rosentopf, a fragment of a farcical Lubitsch feature. Ernst plays his Sally character, now a detective investigating a flower-pot mystery. Lively enough, the surviving nineteen minutes from early scenes didn’t give me much sense of the whole.

Alongside it were two other comedies. Gräfin Küchenfee featured Henny Porten in a dual role, both countess and kitchenmaid. When the countess goes off to have fun, the maid assumes her identity. Eventually, the two women switch roles when the countess tries to evade police charges by pretending to be the maid. No less predictable in its comic situation was Puppchen, in which a young woman working in a fashion salon breaks a lifelike mannequin and must take its place. It may have been a model for Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (1919).

Stylistically, all these films were fairly staid, with little intricate staging, and they lacked analytical editing apart from axial cuts in and out. Their reliance on longish takes probably reflected the fact that US films, with their bold continuity editing, weren’t available in Germany until somewhat later.

One American film also rejected the emerging Hollywood style, in the name of naivete and fancy. That was Prunella by Maurice Tourneur. It doesn’t survive complete, and it’s been known for many years as a failed venture into artiness. The flat sets resemble children’s book illustrations, and the performance style is wilfully arch. I’ve never found Prunella very interesting, but it does offer further evidence that the 1910s harbored some eccentric and ambitious experiments.

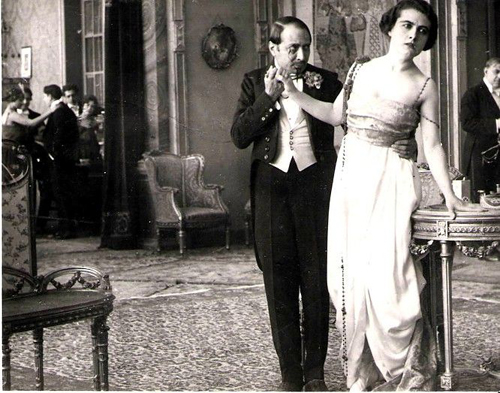

Gustavo Serena’s L’Avarizia impressed me more. It too relies on frontal acting and axial cutting, but as a vehicle for the great diva Francesca Bertini it seemed to me completely engrossing.

As part of a series illustrating the Seven Deadly Sins, it offers a starkly symmetrical plot. Maria and Luigi love each other, but each is dominated by an old miser. Her aunt and his father each amass a fortune in secret while manipulating the young people. Through a series of conspiracies and misunderstandings, the lovers are flung apart. Maria, friendless and illiterate, sinks down, down into the bottom of society.

Each step of the way is given powerful expression by Bertini’s face, gestures, and bearing. She grabs her hair to yank her head back; she blows cigarette smoke in Luigi’s face to show her contempt for his abandonment of her. At one high point, when Luigi falsely accuses her of infidelity, she wrestles with him on a tabletop, giving no quarter. In a tavern fight she pulls a knife before falling to the floor, writhing feverishly in what appears to be her last moments on earth. This is silent opera, with the soaring melody carried by the body.

Up against the fourth wall

A meeting of the Antifeminist Club (The Oriental Language Teacher).

I wasn’t surprised to find a diva film full of sensuous appeals, but the big revelation of the 1918 cycle so far was the Czech comedy The Oriental Language Teacher (Učitel Orientálních Jazykû). It showed what you could do with a small cast, a few sets, and a cut-and-dried situation.

Sylva secretly falls in love with Algeri, who’s tutoring her in Turkish. After her father is being considered for a diplomatic post in Turkey, he decides to learn the language. He arrives during one of Sylva’s lessons, so she quickly disguises herself as an odalisque. Needless to say, Father is smitten with this exotic beauty. Add in his membership in the Antifeminist Club, led by a comic geezer who enjoys snapping clandestine photos of passing women, and insert deceptions involving a pianola roll, and you have some substantial complications.

Most striking from a pictorial standpoint were the very deep sets–modeled, stylistic historian Radomir Kokes tells me, on the Danish cinema of the period. The co-directors Olga Rautenkransovå and Jan S. Kolár present Sylva’s parlor in an unusual way. Most films of the period put foreground desks and tables at a diagonal bias. But here the father’s desk is thrust very close to us, perpendicular to the camera, and it runs the entire length of the frame.

Moreover, the father is centered at his desk, when the more normal placement would set him to left or right and clear a space in the other half of the frame for other characters. The depth, that is, is typically horizontal. Here, though, it’s also vertical. A character must descend the stair directly above the other, in a maniacally centered composition that’s mildly beguiling in itself.

The set depicting Algeri’s studio is a little more typical of the period, since his desk is placed off to one side, but every shot of this setup makes the foreground area curiously out of focus.

Given that the control of focus is precise in the parlor shots, the slightly fuzzy foreground of the studio set remains anomalous–an error, or a decision to differentiate the two spaces more sharply. In any case, here’s another example of how 1910s movies, from all corners of the world, can set you thinking about the possibilities of pictorial design.

More to come in the next entry, with a special focus on trial films.

Special thanks to Radomir Kokes for help with this entry. More generally, thanks to the Bologna leaders and staff for a tightly-run and ever-exciting event, along with the archivists who made these films available. In particular we owe a lot to Marianne Lewinsky, who curates the Cento Anni Fa series, and to Dave Kehr who, grinning, shares what he called on the first day MoMA’s “mildly obscure” treats. And Imogen Sara Smith gave an exceptionally lucid introduction to Seed.

For more on diva acting, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, a book available here, and this entry by Lea on Bertini. Kristin wrote about Prunella and other mildly experimental Hollywood films in Jan-Christopher Horak’s Lovers of Cinema collection.

For more on-the-spot pictures, check our new Instagram page.

John Bailey, President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Michael Pogorzelski.

Posted in 1910s cinema, Directors: Lubitsch, Directors: Stahl, Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato, Film comments, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, National cinemas: Germany, National cinemas: Italy, Tableau staging |  open printable version

| Comments Off on More Bologna bounty open printable version

| Comments Off on More Bologna bounty

|