Monday | February 5, 2018

The Player (1992).

Jeff Smith, our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction just recorded an installment of our Observations on Film Art series for the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck. Here’s a supplement to that. –DB

In my installment, focusing on genre play in The Player, I discuss Robert Altman’s film in relation to two important traditions in Hollywood cinema: crime thrillers and films about filmmaking. As anyone who knows Altman’s other films would expect, The Player toys with the conventions of both genres in a number of different ways.

As I note in the video, The Player was received as something of a comeback film for Altman. It augured a resurgence in the director’s career that ultimately produced such late masterpieces as Short Cuts and Gosford Park.

Today, I sketch out some additional ideas about The Player’s use of genre conventions. I hope to shed light on some other connections to the crime thriller that I didn’t discuss in the video. I also hope to show just how unusual the film is in this context. Spoilers ahead, not only for The Player but for the novel and film of The Ax.

Will the real Griffin Mill please stand up?

In Reinventing Hollywood, David notes that there are usually four sorts of characters involved in a crime thriller plot: victims, lawbreakers, forces of justice, and more or less innocent bystanders. Filmmakers customarily organize the film’s narration around one or more of these character roles. Typically, a cascade of further choices flows from this initial decision about whose perspective forms the focal point of the story.

In The Player, much of the narration is restricted to the knowledge of the protagonist, Griffin Mill. The film includes a few scenes where Griffin is not present, like the one where the studio’s management awaits his arrival at a meeting. That, in itself, is not unusual. Many thrillers, like Chinatown or The Ghost Writer, employ similar tactics. What is slightly unusual is the fact Griffin takes on two of the typical character roles in the crime thriller as both victim and lawbreaker.

Griffin is a suit, and as a studio functionary he doesn’t immediately engender audience sympathy. Our first glimpse of Griffin shows him listening to pitch sessions. His questions to the people proposing new film projects are glib and capricious, representing the worst aspects of Hollywood commercialism.

Yet The Player does marshall some sympathy for Griffin as the victim of a stalker. Every time Griffin finds a postcard in his mail or on his car, it reminds us that he might be in mortal danger. After the stalker plants a venomous rattlesnake in Griffin’s passenger seat, we can’t believe the threats are empty.

Any sympathy that Griffin garners as a result of this psychological warfare is mollified, though, when the victim becomes victimizer. As Griffin later explains to June, his job is to tell people “no” more than a thousand times each year. Griffin believes that one of these rejections is the reason for the threatening postcards he receives. But he tragically miscalculates in targeting aspiring screenwriter David Kahane as the likely suspect.

Griffin contrives a meeting with Kahane at a Pasadena movie theater, and having bumped into him, tries to make amends. Yet Kahane recognizes that he is being pimped. This leads to a shouting match in a parking lot with Kahane threatening to ruin Griffin’s reputation. And when Kahane accidentally knocks Griffin over with his car door, Griffin reacts with rage, grabbing the screenwriter’s head and banging it repeatedly against the lot’s concrete surface. Although it seems clear that Griffin was acting on impulse, he’s nonetheless crossed a line that separates victims from perpetrators.

More importantly, Griffin’s violent action complicates the viewer’s allegiance to him. Altman establishes a dramatic context in which the motivations for Griffin’s crime seem completely understandable. Yet whatever sympathies viewers might have for Griffin are muddled by his creepy romantic interest in Kahane’s girlfriend; his cruel treatment of Bonnie, his current partner; and the general smarminess he exudes as a successful but shallow executive. Crime thrillers often ask audiences to sympathize with heels. There’s nothing that Griffin does that is inherently evil, but there’s nothing to really like. It’s less about his crime and more about his slime.

Griffin’s passage from victim to lawbreaker also alters the typical thriller plot. At the start of the film, Griffin himself functions as the investigative agent, trying desperately to figure out who is threatening him. Once Griffin becomes a suspect himself, though, that line of action halts, and the Pasadena police’s investigation of Kahane’s death springs up in its place.

This shift in the direction of the plot doesn’t really change the film’s pattern of narration. We remain as ignorant of the police’s activities as Griffin is. What does change are the stakes of the narrative. Instead of eliciting curiosity and suspense about Griffin’s stalker, we now wonder whether he’ll ever be brought to justice for Kahane’s death. Despite its strong connections and frequent allusions to crime fiction, The Player is not so much a whodunit as it is a will-he-get-away-with-it.

They smile in your face, all the time they want to take your place….

Besides blurring the boundaries between Griffin’s role as both victim and lawbreaker, The Player falls into a specific subgenre of crime fiction: the corporate thriller. Since, the corporate thriller is mostly defined by its setting, it blends pretty easily with the typical thriller plots and characters.

Like the spy thriller, the corporate thriller can focus on protagonists engaged in industrial espionage, as we see in Duplicity, Demon Lover, or Paycheck. Christopher Nolan’s Inception blends the plot mechanics of these corporate espionage thrillers with science fiction tropes to provide a narrative frame, but then embeds elements of the heist film within it.

Like the political thriller, the corporate thriller might also focus on the backroom deals and machinations that enable the protagonist to move up the company ladder. A film like Disclosure is a paradigm case. But even romantic comedies or prestige dramas can borrow elements from it. (Think Working Girl and Glengarry Glen Ross.)

More commonly, though, corporate thrillers feature elements drawn from the crime thriller. The roots of this approach to the genre stretch back a long way and can be found in both literary and cinematic antecedents. Some plots, for example, follow investigations that expose corporate malfeasance. Others focus on murders committed within a corporate environment, as in Dorothy Sayers’s novel Murder Must Advertise and Kenneth Fearing’s novel (and film) The Big Clock and in more modern instances like Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun and John Grisham’s The Firm. Other corporate crime thrillers, like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (below) and Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer, involve serial murders in white-collar environments.

The corporate crime thriller enables writers and filmmakers to explore thematic parallels between the acts of brutality and violence committed by individuals and the cutthroat tactics employed by business institutions. The plots of many gangster films center on rival mobs battling for competitive dominance in black market trades. Such conflicts often seem like a logical extension of the laissez-faire principles that undergird capitalism. Corporate crime thrillers tread similar thematic territory. They sometimes suggest that the personality traits that make for good business executives and titans of industry are the same ones that produce sociopaths and serial killers.

The Player presents the familiar corporate-thriller rivalry, as Griffin works behind the scenes to outmaneuver Larry Levy. For example, Griffin momentarily ponders using Larry’s admission that he attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings as a way of embarrassing him within the company. Larry quickly undercuts this strategy, though, when he states that he just goes to the meetings because they are a great place to network.

Even more telling is Griffin’s efforts to saddle Larry with a loser project, Habeas Corpus. Midway through The Player, Griffin makes a deal with Andy Civella and Tom Oakley at a Los Angeles restaurant. The next day, he convinces his boss to greenlight the project with Larry as producer, knowing that Tom will likely prove difficult to work with and that his plan to use unknown actors has disaster written all over it. Larry, though, has the last laugh when we get a sneak peek of Habeas Corpus at film’s end. Not only does it have big stars in Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis. It also has the kind of happy ending that the pretentious Tom claimed was too Hollywood when he pitched the project. It turns out Tom cares more about the results of preview screenings than he does the purity of his artistic vision.

Not surprisingly, Altman doesn’t give us a wholly straightforward version of the corporate thriller. In a reflexive and ironic touch, Griffin’s successful ascent to studio boss seems to be secured by the same mysterious stalker who’d been taunting him at the start of the film. In a phone call, the stalker pitches Griffin the plot of the film we’ve just been watching, using his knowledge of Griffin’s crime to leverage his project into development. Here we see Altman slightly reframing the genre’s thesis about the relationship between crime and business. Griffin’s pact with his blackmailing stalker is simply a mildly illicit version of the sorts of quid pro quo arrangements upon which thousands of business deals are made.

If Griffin’s efforts to forestall a rival evoke the political thriller, then his killing of screenwriter David Kahane connects The Player to the corporate crime thriller. Once again, Altman deviates from some of the conventions. The crime doesn’t take place inside a corporate setting, as in Rising Sun and Murder Must Advertise. Griffin kills Kahane in the very public space of a Pasadena parking lot, with film noir overtones.

Similarly, Griffin’s victim is not a colleague, co-worker, subordinate, or client. Rather, Kahane is someone with whom Griffin has had minimal contact, a name plucked almost randomly from a directory of screenwriters in order to jog Griffin’s memory. Consequently, Griffin’s motives for confronting Kahane seem quite different from the culprits in other corporate crime thrillers. More often than not, the murderers in these other stories fear job loss or try to silence others in an effort to cover up some smaller crime or bungled action. Griffin’s actions with Kahane spring from fear about threats to his physical well-being, not from threats to his continued employment. (The latter is Larry’s role.)

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area. Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Like Altman, Westlake has some fun with his central conceit. Just as The Player includes faux film clips and rushes as a means of satirizing Hollywood production practices, The Ax incorporates fictional resumes that tweak jobseekers’ business-speak. What makes Westlake’s social criticism in The Ax so resonant, though, is the utter banality of Burke’s ambitions. He doesn’t aspire to the garish lifestyle we see displayed by Tony Montana or Jordan Belfort in Scarface and The Wolf of Wall Street respectively. Instead Burke just wants to return to his modest middle-class lifestyle and to the dignity that a decent job afforded him. Serial murder just seems like the simplest way to achieve that.

As this comparison suggests, one of the things that makes The Player somewhat unusual as a corporate crime thriller is its play with character motivation and point of view. Facing threats and intimidation, Griffin looks more like the target of a crime than a perpetrator. In corporate thrillers, the lawbreaker is more likely to be somewhere in the middle of the corporate ladder, like Burke, than at the top of it. Moreover, although his actions are motivated by a strange combination of both vanity and insecurity, Griffin more or less stumbles into the crime he commits rather than coolly plotting it the way Burke does.

Despite these differences, The Player and The Ax share an important feature that markedly deviates from the crime thriller as a whole. Both Griffin and Burke get away with it. The plots of most crime thrillers resolve in ways that balance the scales of justice. The bad guys are usually either arrested or killed after climactic confrontations with law enforcement. But this doesn’t always happen. Burke, Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, and Dorine in Office Killer escape punishment. Even though Jordan Belfort is arrested in The Wolf of Wall Street, he gets a slap on the wrist for his crimes.

Perhaps this aspect of the corporate crime thriller reflects the cynicism and amorality that pervades the genre. After all, if your belief is that most corporations get away with murder in a figurative sense, then it’s not hard to accept this idea when it occurs in fictional contexts in a literal sense.

Still, in the case of The Player, the Pasadena police’s failure to prove their case against Griffin Mill may reflect a meshing of both authorial and generic tendencies. When Griffin embraces June in the stylized happy ending of The Player, it quite deliberately parallels the tacked on happy ending of Habeas Corpus we’ve seen just moments earlier. The dialogue Griffin exchanges with June amplifies the similarity between these scenes. When June asks, “What took you so long?”, Griffin responds, “Traffic was a bitch.” These are the exact same lines exchanged by Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis in Habeas Corpus. By allowing Griffin to get away with it, The Player’s “up” ending sharpens Altman’s critique of Hollywood convention, and allows him to subvert the kinds of mainstream genre filmmaking he’s long detested.

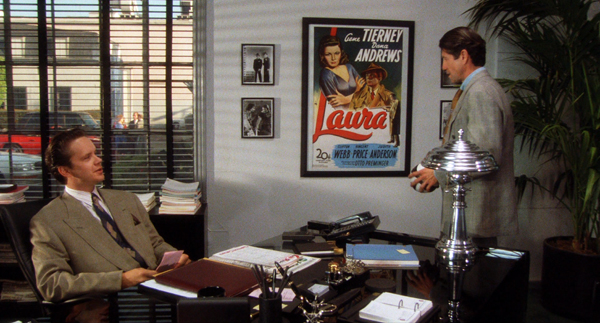

Both allusive and elusive: Comparing The Player to Hollywood Story

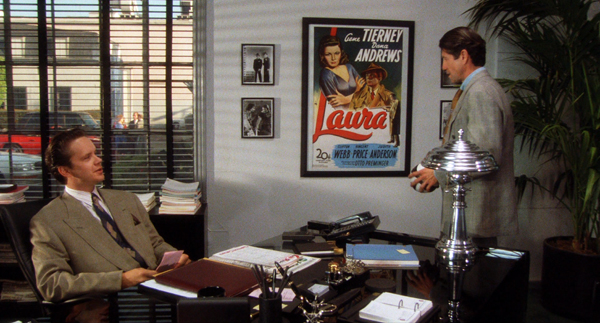

One of the other topics I discuss in my video essay on The Player is the way the film pays homage to various aspects of Hollywood tradition. Much of this is bound up with its satire of commercial filmmaking. But it also strengthens the film’s relation to the crime thriller. Throughout The Player, Altman makes reference to Hollywood’s past in multiple ways. Celebrity cameos, film posters, and production stills populate the mise-en-scene. The characters also frequently mention older film titles in dialogue.

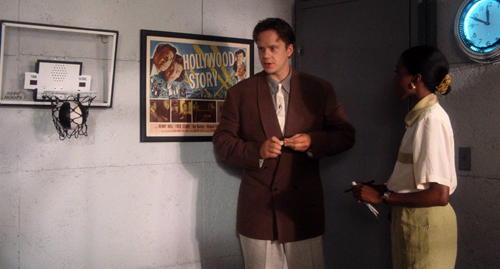

Perhaps the most interesting allusion in The Player involves a poster of Hollywood Story that hangs in Griffin’s office. The latter is a 1951 film noir directed by William Castle, who later became famous for his use of outrageous gimmicks in the production and promotion of horror films. For The Tingler, Castle supervised the installation of devices that would vibrate theater seats, anticipating today’s 4DX Theater Experience in places like Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Orlando.

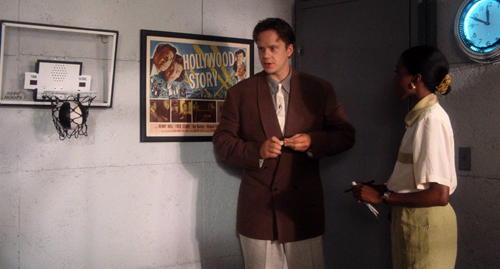

Hollywood Story dramatizes the efforts of film producer Larry O’Brien to develop a project around the unsolved murder of silent film director Franklin Ferrara. O’Brien hires one of Ferrara’s old scenarists to write the script. He also develops a close relationship with Sally Rousseau, the daughter of one of Ferrara’s biggest stars. Once the project is announced, O’Brien finds himself the target of an assassin’s bullet. He surmises that his assailant is trying to prevent the case from being reopened. And as Sally reminds O’Brien, he doesn’t have an ending to his movie is he can’t determine the killer’s identity. O’Brien, thus, sets out to solve the crime, bringing closure to one of the biggest scandals in Hollywood’s history. Hollywood Story offers an even better synthesis of The Player’s mixture of industry exposé and crime film story beats. O’Brien’s lone wolf investigation is treated as being a necessary stage of project development.

If the Franklin Ferrara story sounds vaguely familiar to you, well….it should. Hollywood Story offers a fictionalized account of the unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor, who was shot to death in his bungalow in the wee hours of a February night in 1922. (David blogged about the crime here.) The subsequent investigation of Taylor’s death ensnared some of the industry’s biggest stars of the period. Mabel Normand’s reputation was tainted by her association with Taylor and by reports of drug use. She took a brief hiatus from filmmaking because of the scandal, but never completely recovered from it. Normand later died of tuberculosis in 1930 at the tender age of 37.

As a fictionalized account of a notorious unsolved crime, Hollywood Story anticipates more modern thrillers that provide speculative solutions to real-life murders. Zodiac and The Black Dahlia are prime examples, as are any number of Jack the Ripper films. Hollywood Story’s approach was not unprecedented. James M. Cain based Double Indemnity on the Ruth Snyder case that was fodder for New York tabloids in the late 1920s. That said, Taylor’s death lingered for decades in popular memory in a way that the Snyder case did not.

What are we to make of The Player’s citation of Hollywood Story? On the one hand, viewers might well notice the almost immediate parallel of our “film execs in jeopardy” storylines. Just as Griffin is stalked by an unknown assailant, so, too, is Larry the target of a shadowy aggressor. Moreover, Hollywood Story, along with Sunset Boulevard, might well be an inspiration of one of The Player’s most interesting features: its intermingling of real life stars with fictional characters. Hollywood Story includes cameos by Joel McCrea and several noted performers of the silent era, such as William Farnum, Francis X. Bushman, and Betty Blythe (below). The Player pushes this aspect of Hollywood Story to extremes, containing plentiful cameos by Cher, Jack Lemmon, Burt Reynolds, Lily Tomlin, Susan Sarandon, and other A-listers.

In several other respects, though, The Player seems like an inversion of Hollywood Story with Griffin emerging as a more venal counterpart to the latter’s crusading producer, Larry. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s investigation actually produces results. This strongly contrasts with Griffin’s guesswork, which, as the result of a tragic mistake, leads to David Kahane’s death in a Pasadena parking lot. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s blossoming romance with Sally furnishes the standard double plotline commonly found in classical cinema. In The Player, though, Griffin’s interest in June seems genuinely sleazy. It also exacerbates the Pasadena police’s doubts about Griffin’s alibi, making him their prime suspect. Finally, the revelation of screenwriter Vincent St. Clair as Franklin Ferrara’s killer provides closure both to Larry’s script and to Hollywood Story itself. In contrast, none of the crimes presented in The Player are really solved. Griffin is blackmailed into greenlighting a project during the film’s epilogue, but the audience never learns the identity of the mysterious stalker. Similarly, although the Pasadena police believe that Griffin is guilty of murder, the botched lineup ensures that he will go free and that David Kahane’s death will remain an unsolved crime. In an odd way, The Player returns to the narrative roots of Hollywood Story. The fate of Kahane, our aspiring screenwriter, seems destined to mirror that of poor William Desmond Taylor, our successful silent film director.

A thriller with no thrills

I’ve sketched out a number of different ways in which The Player relates to the basic conventions of the crime thriller, but all of this is ultimately, in the parlance of the genre, a red herring. This is because The Player is that rare bird: a crime film that engenders relatively little curiosity about its solution and even less suspense about the fate of its protagonist.

This is largely because Robert Altman mostly uses crime film conventions as scaffolding for the things that really interest him: quirky characters, digressive dialogue, and a loose, improvisatory feel to the film’s performances. At its heart, The Player is a comedy that draws upon crime film conventions in much the way Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye does.

Compare, for example, each film’s tweaking of the genre’s standard interrogation scenes. In The Long Goodbye, Detective Farmer’s tough questioning of Philip Marlowe is punctured by the latter’s goofy responses. At one point, Marlowe uses the ink from his fingerprinting procedure like it was the “eye black” used by an athlete. Later, he smears the ink all over his face and sings “Swanee” in a mocking homage to Al Jolson in blackface. Similarly, in The Player, the Pasadena police’s interrogation of Griffin is disrupted by Detective Avery’s disarming exchange with her partner about tampons, her mangled pronunciation of “Gudmundstottir,” and her dialogue with Paul about Todd Browning’s Freaks.

The Player has many ingredients characteristic of crime films: a dead body, an investigation, a shady suspect, and a campaign of stalking and extortion. Yet, by the time Altman’s film reaches its ironic and deeply reflexive conclusion, viewers might well conclude that they are the ones who just got played.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their Criterion colleagues. A list of our Observations on Film Art series is here.

For more on Robert Altman’s career, see Patrick McGilligan’s excellent biography, Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. There are also several books featuring interviews with the iconoclastic director. These include David Sterritt’s Robert Altman: Interviews, Mitchell Zuckoff’s Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, and David Thompson’s Altman on Altman.

Those interested in learning more about crime fiction should consult Martin Rubin’s Thrillers, Charles Derry’s The Suspense Thriller: Films in the Shadow of Alfred Hitchcock, John Scaggs’s Crime Fiction, Richard Bradford’s Crime Fiction: A Very Short Introduction, and Martin Priestman’s The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction.

Hollywood Story (1951).

Posted in Directors: Altman, Film and other media, Film comments, Film genres, FilmStruck, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Hollywood: The business, Narrative strategies, Narrative: Suspense |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Who got played? A guest post by Jeff Smith on THE PLAYER open printable version

| Comments Off on Who got played? A guest post by Jeff Smith on THE PLAYER

Friday | February 2, 2018

DB here:

FilmStruck and The Criterion Channel are running His Girl Friday this month, in the fine restoration that Criterion released on Blu-ray last year. Accompanying this rerun is a bevy of bonus materials, including the restored Front Page and a video essay I worked on. There’s a larger thematic bundle on the streaming service as well: “Howard Hawks and the Art of Screwball Comedy,” featuring three other films as well as an 11-minute extra on “The Hawksian Approach to Screwball Comedy” by Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou.

For more on His Girl Friday, you can check two of our blog entries, one on how His Girl Friday got into the canon, and a second with analysis and historical background based on the initial Criterion release.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll go watch it again.

Thanks, as usual, to the Criterion folks–Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker–along with Erik Gunneson and his able staff, all of whom worked on the video essay.

His Girl Friday (1940).

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Directors: Hawks, Film comments, FilmStruck, Hollywood: Artistic traditions |  open printable version

| Comments Off on HIS GIRL FRIDAY never goes away (good thing, too) open printable version

| Comments Off on HIS GIRL FRIDAY never goes away (good thing, too)

Monday | January 22, 2018

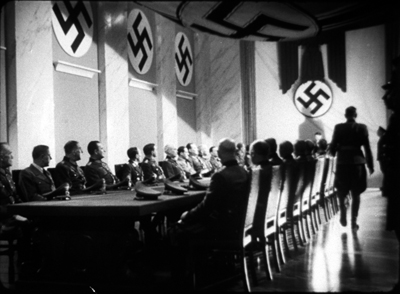

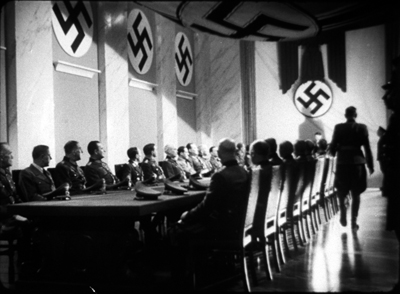

The Fall of Berlin (1950). The Fall of Berlin (1950).

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility. draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.

Tags: Directors: Pudovkin

Posted in Books, Directors: Eisenstein, Directors: Pudovkin, Film history, Film technique: Editing, Film technique: Staging, National cinemas: Russia and USSR, UW Film Studies |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry open printable version

| Comments Off on Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

Friday | January 5, 2018

Silence.

DB here:

This is a sequel to an entry posted a year ago. Like many sequels, it replays the ending of the original.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Parts of those histories are traced in the book that came out in the fall, Reinventing Hollywood. Some of my blog entries have already served to back up one point I tried to make there: that contemporary filmmakers are still relying on the storytelling techniques that crystallized in American studio films of the 1940s.

Relying on here means not only utilizing but also, sometimes, recasting. In keeping with earlier entries (including one from the year before last), I want to explore some films from 2017. These show that the process of schema and revision creates a tradition. Hollywood is constantly recycling, and sometimes revitalizing, Hollywood.

Of course here be spoilers.

Back to basics

The Big Sick.

The US films I’ll be considering all adhere to canons of classical Hollywood construction. Some of these are laid out in the third chapter of Reinventing.

Classically constructed films have goal-oriented protagonists who encounter obstacles, usually in the form of other characters. The goals are often double, involving both romantic fulfillment and achievement in some other sphere. (Somewhere Godard says that love and work are the only things that matter. Hollywood often thinks so too.) Alternatively, the goal might be prodding someone else to action (Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri). Often there’s a clash between the goals, as when work tugs the protagonist away from love (La La Land).

The plot is typically laid out in large-scale parts. A setup is followed by a complicating action that redefines character goals. In Downsizing, once Paul has gotten small, he has to reconceive his goals in the face of his wife’s last-minute defection from their plan. There follows a development section that delays goal achievement through characterization episodes, backstory, subplots, parallels, setbacks, digressions, twists, and new obstacles. That marvelous slab of show-biz schmaltz, The Greatest Showman, relies for its development on a potential love triangle and a secondary couple’s romantic intrigue.

There follows a deadline-driven climax that resolves the action and an epilogue (sometimes called the tag) that celebrates the stable state achieved and perhaps wraps up a motif or two. The Greatest Showman presents Barnum’s success in creating a genuine circus and reconciling with his family. The tag shows a big production number, with the subplot resolved (Carlyle embracing Anne) and the motif of swirling points of light—initiated in Barnum’s spinning Dreams gadget—washing over the final spectacle and his daughter’s ballet performance.

Classical narration—what’s usually called point of view—typically attaches us to the main characters. But not absolutely: we’re usually given access to things they don’t know, mostly for the sake of arousing curiosity and suspense. And throughout, the film is bound together through recurring motifs that reveal character (and character change) or significant plot information. Think of the roles Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 assigns to “Brandy, You’re a Fine Girl,” Pac-Man, David Hasselhoff, and that “unspoken thing.”

Or take The Big Sick, a semi-serious romantic comedy. Kumail’s initial goal is success in standup comedy, but he also falls in love with Emily. His Pakistani-American family constitutes the main antagonist, as his mother and father want him to go to law school and submit to an arranged marriage. He hasn’t told his family about Emily, which precipitates the couple’s big quarrel: “I can’t lose my family.” Kumail’s goal shifts when Emily is stricken by a mysterious disease. In the development section , as she lies in a coma, he gets to know her parents, and a tense sympathy develops between them. The crisis comes when Kumail confesses his true goals to his parents, they disown him, and Emily’s disease hits a life-threatening phase.

In the climax portion, Emily revives and breaks off with him, his parents grudgingly accept his move to New York, and he mounts a somewhat successful one-man show there. The film is tightly tied to Kumail’s range of knowledge, so we’re surprised when he is—as when Emily’s parents decide to move her to another hospital, and when Emily pops up in his New York audience, ready to reconcile with him.

The Big Sick exploits many comic motifs: the parade of would-be fiancées Kumail’s mother invites to dinner, the photos he keeps of them (which ignite Emily’s jealousy), the repeated sit-downs he has with his family, the dumb catchphrases deployed by other comics, and especially Emily’s “Woo-hoo!” heckling, which eventually attests to the rekindling of their love.

The power of classical plotting is shown in its ability to spotlight a Pakistani-American protagonist, an Islamic family demanding that a son adhere to tradition, and the pathos of parents facing the death of a daughter. But that ability to flexibly absorb new subjects and themes and emotional registers has kept the classical template going for about a century.

Time travel

Wonder Woman.

One of the hallmarks of Forties cinema, I argue in Reinventing’s second chapter, is a eagerness to explore what flashbacks can do. Flashbacks were already well-established, but a more pervasive acceptance of nonlinear storytelling, so familiar to us now, became firmly part of Hollywood sound cinema in this period.

One-off flashbacks are so common now we don’t particularly notice them. In The Big Sick, when Kumail visits Emily’s apartment with her parents, he peeks into her closet, and we get glimpses of her wearing the outfits earlier in the film. In this case, flashbacks function as memories. At the climax of Guardians 2, Quill flashes back to moments of listening to music with his mother. Similarly, in Get Out, Chris recalls his childhood TV viewing and, at the climax, he remembers earlier moments at the Armitage garden party when he asks, “Why black people?”

Flashbacks usually aren’t pure representations of memory, though. They often include information that the character doesn’t or couldn’t know. In fact many flashbacks are addressed simply to us, coming “from the film” rather than from a character’s mind. These may remind us of things already seen, or fill in gaps, or plant hints about things that will develop.

So, for instance, in Logan Lucky, when Logan says, “I know how to move the money,” we get a flashback to him studying the pneumatic pipes that feature in the heist plan.

He’s not necessarily recalling the moment; the filmic narration seems merely to be tipping us the wink. At the climax, other “external” flashbacks plug gaps we didn’t notice earlier. These reveal some aspects of the heist we weren’t aware of, such as the extra bags of money carried off.

1940s filmmakers also explored how flashbacks could be “architectonic,” how they could inform the overall shape of the movie. Here the flashback rearranges story order to build up curiosity and suspense, and it may come from purely from the narration or be motivated as character memory.

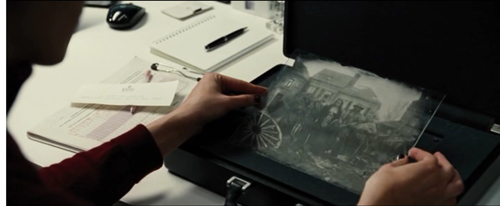

One large-scale pattern is the extensive embedded flashback, as in How Green Was My Valley, I Remember Mama, and innumerable biopics. Wonder Woman gives us a framed inset of this sort, when a modern-day Diana opens the chest harboring the World War I photo. That scene segues to the past. The origin story and war episodes are ultimately closed off by a return to the present, and a reminder of a motif—Steve’s watch (which, in one of the film’s jokes, stands in for something more private). The purpose of this is to provide what I call in the book “hindsight bias.” While building curiosity about the past, the opening primes us to expect certain things to have been inevitable (such as chance meetings).

Another common framing strategy begins at the climax and then a long flashback lays out the conditions that led up to it. A reliable source tells me that Pitch Perfect 3 does this, starting with an explosion followed by a title announcing that the action began three weeks earlier. In films like this, there may be no closing frame; the internal action of the flashback catches up, perhaps via a replay, with what we saw at the outset, and the film proceeds to the resolution and epilogue. The somewhat phantasmic opening number of The Greatest Showman comes to fruition during the finale.

To and fro

Loving Vincent.

Sustained blocks like this are fairly rare nowadays, I think. More common, as in the Forties, is an alternation of past and present. The main examples in Reinventing Hollywood include Passage to Marseille, The Locket, Lydia, Kitty Foyle, and Sorry, Wrong Number. Again, though, these are motivated as memories, while current examples tend to be more “objective.”

A simple instance is Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. Here clusters of events in 1981 alternate with incidents in 1979: Gloria Grahame returns to her young lover, and we flash back to their earlier affair. Neither protagonist is firmly established as recalling the 1919 events. Another feature of 1940s flashbacks, the replay from different viewpoints, comes in here as well. The couple’s crucial quarrel in New York is shown first from Peter’s perspective, and later from Gloria’s. He suspects her of infidelity, but we learn that her secret involves her cancer. As often happens, our restriction to the protagonist is modified by knowledge he doesn’t gain at the moment.

The alternation of past and present is given a more geometrical neatness in Wonderstruck. In maniacally precise parallels, Rose in 1927 runs away to Manhattan to find her mother, while in 1977 Ben runs there to find his father.

The parallels are reinforced by a host of motifs: wolves, movie references, the asteroid in the Museum of Natural History, a bookmark, and so on. The linear chronology gets straightened out, and the gaps filled, by an integrative flashback played out among miniatures and cutouts adapted to the scale model of Manhattan. The dovetailing flashbacks create a sense of cosmic design; in many films, convergences like these can suggest destiny.

For modern audiences, Citizen Kane is the prototypical flashback film of the 1940s, and its investigation structure, while not completely original, was hugely influential. I was surprised to see Kane’s schema revived this year in Loving Vincent. Once the postman has given Armand his mission, to take Vincent’s last letter to brother Theo, we embark on an inquiry into Vincent’s life and death. It’s refracted through the testimony of many who knew him during his sojourn in Arles. Armand’s goal gets recast when he learns of Theo’s death, but in the course of his travels he comes to understand how Vincent’s kindness and art touched many lives.

As in several Forties films, Loving Vincent’s past scenes jumbled out of chronological order, so we must piece together the story Armand gradually discloses. And there’s the driving force of mystery, a distinctive thrust in many Forties genres, for reasons I talk about in one chapter of Reinventing. Very modern, and not so much like the 1940s, is the brief, fragmentary quality of the flashbacks; I counted thirty-six of them.

The boldest experiment in nonlinear time I saw this year was Dunkirk. The film juxtaposes timelines consuming a week or so, a day, and an hour, and then aligns them in unexpected ways. In this staggered array, the distinction between flashbacks and flashforwards loses its force. Any cut may constitute a jump ahead of the moment just shown, or a jump back to an earlier incident. Christopher Nolan has acknowledged the influence of 1940s cinema on his thinking about time schemes, and here he explores yet again how crosscutting different lines of action can stretch or condense story duration.

Their eyes and ears

Get Out.

Like flashbacks, subjectively tinted storytelling has a long cinematic lineage. Silent films displayed dreams, visions, anticipations, and deformations of mind and eye. Those devices mostly dropped out of 1930s American cinema, which was to some extent more “objective” and “theatrical” in its mode of presentation. Subjectivity came roaring back in the Forties, which is why Reinventing Hollywood devotes two chapters and several other passages to various techniques that go beneath the surface.

Memory-based flashbacks are common options today, but the inward plunge can take other forms. For most of its length, Get Out restricts us to Chris’s range of knowledge, and it relies on optical POV in many stretches. Through his eyes we see Mrs. Armitage staring at him while stirring the tea.

More complex is his view of Georgina at the upper window. That’s followed by a shot going beyond his range of knowledge: she’s looking not at him but herself.

We take a deeper dive into Chris’s mind under hypnosis. The boy Chris sinks into a stellar cavity and becomes Chris staring at Mrs. Armitage as if she were appearing on the TV screen. The shift dramatizes his guilt at his mother’s death and his susceptibility to this Bad Mom figure.

Once Chris becomes a prisoner, the narrational range widens again to show Rod’s efforts to rescue him, along with the family’s plans for him. But the film tightly realigns us with Chris at the climax, so that the attacks from Rose, Jeremy, and others come as surprises.

Chris, a photographer, channels his experience through vision, though the hypnotism scene blends sounds from the present with the rain drizzling in the past. Subjectivity goes more fully sonic in Baby Driver, about a whey-faced lad who lives in the auditory ether.

Edgar Wright, now exercising straight the percussive dashboard details he parodied in Hot Fuzz, punches up the visual exhilaration of Baby’s rubber-shredding takeoffs and getaway 180s. He locks us into Baby’s auditory world as well. We’re almost completely attached to Baby, learning what he learns when he learns it. Notably, the robberies are rendered from his perspective, including optical POV shots as he waits in the getaway car.

Again, fragmentary flashbacks replay his mother’s death and the childhood damage to his hearing. We even get a fantasy, with Baby imagining his escape with Debora in black and white.

What’s just as subjective, though, is the music Baby incessantly cues up on his iPod. Blocking out the shriek of his tinnitus, it provides a soundtrack to his life—danceable tunes as he bops down the street, ballads when he flirts and falls in love with Debora, and pulsing rock during robberies (what the psycho Bats calls, “a score for a score”). Through volume and texture, Wright suggests that we hear the music as Baby does; only the loudest environmental sounds poke through. Sometimes, when he pulls out one earbud, the volume drops. His growing attachment to Debora is signaled by his dialing up a song using her name and sharing his precious buds.

Some scenes are handled objectively, as we witness the gang’s conversations in front of Baby. He can read lips, though, and he can keep the iPod cranked up. So a little bit of Baby’s custom soundtrack leaks in for us underneath others’ dialogue. At other times, the score takes over to become nondiegetic accompaniment, as when gunshots in a firefight land on the off-beats of “Tequila.”

As you’d expect, the music comments on the action throughout (“Never ever gonna give you up” when Baby defends Debora from Buddy) and supplies motifs. Queen’s “Brighton Rock,” Baby’s favorite heist accompaniment, briefly enables him to bond with Buddy.

A song about a couple’s devotion reminds us that both thieves are loyal to their women.

Momentary sound changes are rendered through our protagonist’s viewpoint. Wright lets us hear the whine of Baby’s tinnitus as Bats taps his ear. When Buddy blasts his pistols alongside Baby’s head, we suffer his hearing loss and the distorted voices that wobble through it.

Such streams of auditory perception occasionally emerged in early talkies (e.g., Gance’s Beethoven). Those experiments got normalized in 1940s manipulations of sound perspective in different environments. More fancily, in A Double Life (1947), party chatter subsides when the hero covers his ears, and in Pickup (1951), the gradually deafening protagonist hears high-pitched noises. Wright extends these one-off devices to the texture of an entire film.

Confidants

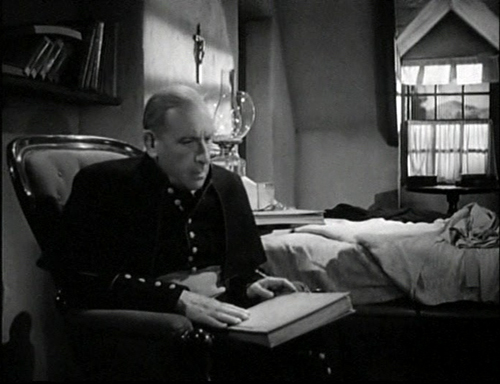

The Keys of the Kingdom (1945).

Large-scale and small-scale, the heritage of the 1940s seems to be everywhere. Many of the flashbacks and fantasies I mentioned already are primed by a track-in to a character’s face, just as in classic studio pictures. There’s also block construction, either unsignaled as in the Wonder Woman and Greatest Showman cases, or signaled, as in the date-stamping in the early alternations of Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. We also get explicit chaptering, as in The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer.

Voice-overs come along with flashbacks, as a way of guiding the audience to understand the time shifts. In the Forties, as I discuss in the book’s sixth chapter, voice-overs became more flexible and fluid. Sometimes they were external, issued from an all-knowing commentator (Naked City and other police procedurals). Sometimes they were sonic equivalents for letters and diaries, letting us in on what characters were writing. Deeper intimacy could come from voice-overs serving as inner monologues, the voice of a character’s mind. These, like flashbacks, are associated with film noir, but also like flashbacks they actually emerge in many genres–as they do today.

The voice-over can be perfunctory, as in All the Money in the World. Young Paul Getty, kidnapped in the opening reel, has a couple passages confiding in us, but he’s not heard from again. Moreover, his explanation of his grandfather’s rise to power (during the inevitable flashbacks) could have been supplied in other ways. Paul baldly tells us that we need to know all this to understand what follows (who’s he talking to?). He admits that he’s an expository shortcut. This is why voice-over is sometimes considered lazy storytelling.

It doesn’t have to be. Take Martin Scorsese’s Silence. In subject and strategy it reminded me of The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), which dramatizes the diary of a young missionary to China. Via this novelistic device, we get flashbacks to his youth and his years of service. We get as well the reaction of the skeptical priest whose voice reads the journal. This fairly straightforward schema is in effect revised by Scorsese and co-screenwriter Jay Cocks, who create a floating dialogue among voice-overs.

After initial exposition via an old letter from Father Ferreira, which is recited in his voice, two young priests set out for Japan. They hope to maintain the clandestine Christian community there, and they want as well to discover if Ferreira has truly renounced his faith . The bulk of their grim adventures is commented on through the voice-over of one of them, Father Sebastião Rodrigues. At first he’s vocalizing a letter, which he calls a report, summing up the struggles of the Jesuit mission and their encounters with Christian villagers. In the course of his report, we also get an embedded flashback narrated by Kichijiro, their guide and a sporadically lapsed believer himself.

But at a crucial moment, Father Sebastião’s report ceases to be such and turns into an inner monologue. Seeing a Christian village devastated by the shogun’s forces, he asks, “What have I done for Christ?”

Soon his voice presents a kind of stream of consciousness–praying for the villagers as they walk off in captivity, thanking God when he has a vision of Jesus on his prison wall. His inner voice urges his colleague Father Garupe, severely tortured, to apostatize.

In last stretch of the film, new voices are heard. There’s Jesus, perhaps filtered through Sebastião’s mind (subjectivity again), and then, more objectively, there’s an account from the Dutch trader Albrecht. He drily reports that Sebastião apostatized and followed Ferreira in leading a Japanese life. Albrecht’s narration is interrupted by a dialogue between Sebastião and Jesus, capped by the priest’s blurting out: “It was in the silence that I heard your voice.” Albrecht’s voice-over concludes the film, with his final claim that the priest was “lost to God” belied by the closing image.

From the 1940s onward, voice-over has been a rich resource–describing settings and external behavior, judging other characters’ motives, giving us access to the deepest thoughts of the speaker. I try to show these capacities at work in a fairly ordinary film, The Miniver Story, but for our time, the soundtrack of Silence is another vivid demo. In the juxtaposition of different voices, it achieves some of the density of a novel, and by the end we better understand the initial words and emotions of Father Ferreira, the priest whose apostasy launches the plot.

Passed-along voice-over gets a bigger workout in Dee Rees’s Mudbound. The original novel is somewhat like As I Lay Dying; its sections set various characters’ voices side by side, shifting viewpoint as each takes up a portion of the tale. Constant commentary and perfect alignment with a character’s range of knowledge are hard to sustain in cinema, so what we have onscreen are objectively presented scenes accompanied by an occasional voice-over. Still, it’s a rare option. If Silence gradually opens its voice-over horizons near the film’s end, Mudbound introduces polyphony from the start. Six characters share their thoughts and feelings in alternation, providing backstory and deepening our access to their reactions.

As in Silence, there’s a pattern to the voice-overs. The bulk of the film is an embedded flashback, triggered by the McAllen brothers setting out to bury their father and encountering the Jackson family riding by.

The intersection of two families sets up not only the flashback episodes but the floating voice-overs. As the visuals anchor us initially to the white family, the first voice-overs issue from Laura, the wife of Henry McAllen, and from Henry’s brother Jamie. In the flashback stretch, as America enters World War II, the voice-overs shift to the Jacksons, the father Hap and the mother Florence. The plot proceeds to add the voices of Henry and the Jacksons’ oldest son Ronsel. All the characters narrate the action in the past tense, as if recalling it from a distance in time, but no listener is ever specified–a common feature of voice-overs in the 1940s and afterward.

During the film’s second half, the development and climax sections, the voice-overs nearly vanish. For over an hour, we hear only Laura and Florence, and only once apiece. Jamie and Ronsel, both disaffected returning vets, don’t confide in us during their growing friendship or during the persecution of Ronsel by the local white men. The women are left to provide a sporadic chorus.

At the end, however, a spurt of brief commentaries give the men their inner voices back. We return to the present and see Hap Jackson help the McAllen men bury their father (the inciter of KKK violence against Ronsel). The epilogue features brief comments from Ronsel, Jamie, and Hap, and not the women. Ronsel gets the last word. Ironically, because of the KKK savagery, this narrator has become mute.

Again, I felt a current film’s kinship to those I studied for the book. Mudbound traces the rural home front, the military experiences of a white man and a black one, and the veterans’ problems of adjustment upon returning home. These elements hark back to some of the powerful films of the 1940s, including Home of the Brave and The Best Years of Our Lives. The sympathetic portrait of African-American families isn’t unprecedented either, as seen in Intruder in the Dust and Lost Boundaries. Mudbound‘s passed-along narration, like the ones we find in other modern films, constitute contemporary revisions of the shifting voice-overs we get in Citizen Kane and All About Eve.

Career women careening

Molly’s Game.

Molly’s Game and I, Tonya offer good wrapup examples of many of these strategies, with some unreliability thrown in.

As you’d expect in a film by Aaron Sorkin, the flashback organization of Molly’s Game is fairly complicated. Just as The Social Network intercut two arrays of flashbacks triggered by two legal inquiries, the new film scrambles together crucial moments in Molly’s childhood , scenes of her current legal troubles, and sequences showing her rise to become the Poker Princess, the arranger of high-stakes games. The film gains a bit of the structural symmetry of Wonder Woman by beginning and ending with a childhood defeat that Molly rises above.

The flashbacks are stitched together by Molly’s voice-over. A filmmaker who recruits a narrating voice has to choose. Do you show the narrating situation? Or do you leave it unspecified? In this last instance, the narration might be wholly internal, a mental summing up of events, or it might feel like a confidence shared with an intimate, even though we’re shown no listeners. In Molly’s Game, her bare-it-all confession might seem to be simply her unspoken thoughts, but at one point it’s suggested that what we’re getting is her book’s version of her life.

Molly’s attorney Charlie is reading her memoir while he researches her case, and he asks her about a passage we saw in a flashback: her boss chews her out for bringing him “poor people’s bagels.” The attorney suggests that nobody uses that phrase, and that probably the boss used a racial slur that she suppressed in the book. This throws a little bit into question the reliability of Molly’s flashback, while also hinting at something we learn later: she sanitized the book to spare the reputations of the high rollers she serviced.

I, Tonya takes another option. Again there are disordered flashbacks and bursts of subjectivity tied together by the voice track. Whereas Molly is the sole speaker in her film, though, Tonya shares the soundtrack with other characters, in the manner of Mudbound. But these commentaries aren’t private musings. They’re the self-justifying testimony of people talking to a documentary camera. (Even though these sequences are said to be occurring forty years after the earliest events, the format is an anachronistic 4:3–presumably to help us keep the time frames distinct.

Once you get characters in conflict recounting past events, you have the possibility of disparate stories. Forties filmmakers exploited this in Thru Different Eyes and a certain Hitchcock film too famous to mention. Tonya says explicitly that there are different versions of the truth. A brief scene shows her battering Nancy Kerrigan, and a more complicated one occurs in a tale recounted by her husband Jeff. She fires a shotgun at him and turns to the camera saying, “I never did this”–before briskly ejecting a shell.

The comic possibilities of to-camera address on display here were exploited in My Life with Caroline, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and other 1940s films. Then the momentary breaking of the fourth wall was reserved for the frame story and kept separate from the embedded flashbacks. But I, Tonya‘s revision is easy to understand as a zany equivalent for her verbalized denial. Given the defiant way she brandishes the gun, we’re permitted to doubt her denial–which means that the film is refusing to settle the matter. The possibility that the overall filmic narration could be unreliable was rehearsed occasionally in the Forties, perhaps most vividly in Mildred Pierce (analyzed here, sampled here).

Other paths

Foxtrot.

The 1940s were important for other national cinemas too. The book’s last chapter suggests that filmmakers in Britain, France, Mexico, and other countries engaged in similar narrative explorations–sometimes in imitation of America, sometimes on their own. I go on to suggest that eventually non-Hollywood narrative models came to international attention, and still later those affected American cinema.

Italian Neorealism was a prime source of alternatives. A good example of its long-term impact, I think, is The Florida Project, which embraces a slice-of-life pattern. Once you’re committed to episodic plotting, you need to organize the incidents coherently. Sean Baker follows European and US indie precedent in tracing a rhythm of daily routines that change in sync with the characters’ relationships. So Halley’s quarrel with her friend Ashley means that Moonee can no longer claim leftover food from the diner, which helps push Halley toward prostitution, which leads to the intervention of child welfare authorities.

The drama arises less from crisply defined goals than from circumstances that alter life routines. In addition, like many Neorealist films and others in this vein afterward, the poignancy gets sharpened by the presence of children caught up in adults’ bad choices.

The Florida Project presents many actions elliptically, leaving us to infer what has happened offscreen. (I think, for instance, that it’s motel manager Bobby Hicks who contacts the authorities, but I don’t think it’s made explicit.) Moving to films made outside the US, Michael Haneke’s Happy End takes ellipsis even further.