Wednesday | December 27, 2017

Underworld.

Kristin here:

Once again it’s time for our ten-best list with a difference. I choose ten films from ninety years ago as the best of their year. Some are well-known classics, while others are gems I have found while doing research for various projects–though I have to admit that most of the films on this year’s list are pretty familiar.

One purpose of this yearly exercise is to call attention to great films of the past, for those who are interested in exploring classic cinema but aren’t sure where to start. (Previous lists are 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, and 1926.)

Hollywood dominates this year, with half the list being American-made.

There are reasons for the lack of international titles. This year was was the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but although Vsevolod Pudovkin’s celebratory film The End of St. Petersburg is here, Sergei Eisenstein did not finish October in time and it came out in 1928. (I remember the third anniversary film, Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October, as good but not necessarily top-ten material.) Some major directors didn’t release a film or made a lesser work. Dreyer was at work on The Passion of Joan of Arc, but it, too, wasn’t released until 1928. Lubitsch made The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, a good but not great entry in his oeuvre. Japan’s output is largely lost. Yasujiro Ozu made his first film in 1927, but his earliest surviving one comes from 1929. Most of Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1920s films are gone, including those from 1927.

1927 was the year when Hollywood dipped its toe in sound filmmaking, but we need not worry about the talkies for now. Instead, all ten titles are examples of the state of sophistication that the silent cinema had achieved by the eve of its slow demise. (Sunrise‘s recorded musical track does not a talkie make.)

Hollywood, comic

The General is often listed as a 1926 film. This is technically true, in a sense, but I choose not to count its world premiere in Tokyo on December 31, 1926. Its American premiere was scheduled for January 22, 1927 but was delayed until February 5 by the popularity of Flesh and the Devil, which was held over in the theater where Keaton’s film was eventually to launch.

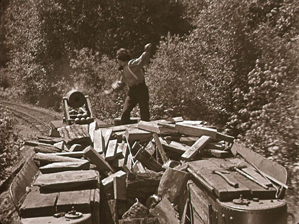

David recently posted an entry on how the great silent comics moved from shorts in the 1910s to features in the 1920s. His example was Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy, one of our ten best for 1924. Keaton moved into features slightly later than Lloyd, excepting The Saphead (1920), an adaptation of a play, in which Keaton was cast in the lead but over which he had no creative control. Once he did tackle features, he soon became adept at tightly woven plots with motifs and sustained gags. The General, based on a real series of events during the Civil War, has a solid dramatic structure that is more than just an excuse for a bunch of humorous bits. (A dramatic film, The Great Locomotive Chase, was produced by Disney in 1956 and based on the same events.)

The French title of The General is Le Mécano de la General. One might call Keaton that, since The General‘s comedy is essentially a long set of variations on the humor to be gotten out of the physical characteristics of a Civil-War-era train and its interactions with tracks and ties. Keaton had always been fascinated by modes of transportation and other mechanical sources of gags: an earlier train in Our Hospitality, boats in The Boat and The Navigator, a DIY house (One Week), film projection in Sherlock Jr., and so on.

At the beginning, Keaton’s character, Johnny Gray, tries to enlist in the Confederate army, but he is rejected without explanation. The officers consider him more valuable as a train engineer. Later, when Johnny is taking troops up to the front, a group of disguised Union soldiers steal his beloved engine, “The General.” Pursuing the thieves, he ends up deep in Union-occupied territory and takes his engine home, just in time to participate in a battle and prove his worth as a soldier.

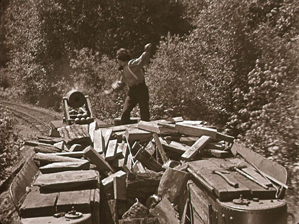

The perfection of Keaton’s construction of gags is evident in one famous scene where Johnny’s engine is towing a cannon pointed up at an angle that would clear the cab if it were fired. Johnny has just loaded it with a cannon-ball and lit the fuse; he is returning to the engine when he foot becomes caught in the hitch attaching the cannon to the fuel car. The hitch drops, jolting against the ties so that the cannon slowly sinks to point straight ahead. A cut to a side view shows Johnny noticing this and panicking.

A view from behind the cannon emphasizes his danger as he starts to climb into the fuel car but gets his foot caught in the chain, a situation made clear by a cut-in. Once he is atop the wood-pile, he throws a log which fails to shift the cannon’s aim.

A cutaway establishes the Union soldiers who have stolen the General, approaching a lake in the background. Back at the pursuing engine, Johnny gets onto the cowcatcher, as far from the cannon as he can get. A return to the previous framing shows Johnny’s engine starting to turn on a curving stretch of track with the lake in the distance. The cannon follows.

As Johnny’s engine moves just out of the cannon’s trajectory, it fires. This would be enough for the pay-off of this elaborate gag, but the smoke quickly blows aside (possibly a wind machine offscreen left?) and we see the explosion in the distance near the General. As so often happens with Keaton’s gags, we are likely to gasp in amazement at the moment’s sheer physical complexity and ingenuity, as well as Keaton’s dexterity, before we start laughing.

The consensus among most critics and historians is that The General is Keaton’s finest film. In my opinion it goes beyond the top ten for a year to the top ten, period. Participating in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll of scholars and filmmakers, I put it in my list of ten films. It only made it to number 34 among voters, but then, my opinions didn’t coincide too well with the “winners.” Only two of the top ten were on my list. Such exercises are hardly definitive, given how difficult it is to choose among films at the highest levels of brilliance. That’s why David and I tend to stay away from them–except for films made ninety years ago.

Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother is similarly one of his finest, along with Girl Shy (featured on my 1924 list and discussed by David in a FilmStruck introduction and his entry linked above). As David points out, Lloyd’s features usually give his character a flaw to overcome. Here, as a country boy overshadowed by his tough father and two older brothers, he believes himself to be timid and not worth much. He eventually proves himself, of course, partly from a desire to save his father, who is wrongly accused of stealing some money, and partly through the encouragement of Mary, owner of a medicine show passing through town, with whom he falls in love.

Harold Hickory is quickly set up as fantasizing that he is as capable as his father, the local sheriff, when he holds his father’s badge against his chest (see the top of this section). Not just a prop for character exposition, however, the badge leads him to be mistaken for the real sheriff. In trying to pass himself off as a convincing sheriff, he sets in motion a series of events that lead to the accusation of theft against his father and his attempts to recover the money from the real thieves.

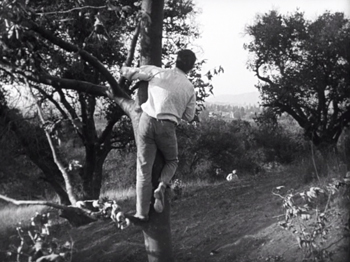

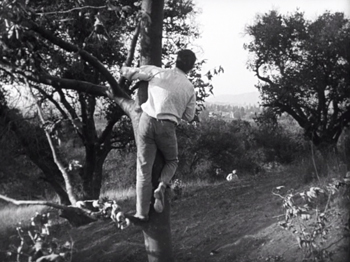

As with Keaton, one of Lloyd’s strengths was an ability to plan a gag to use the whole frame, whether in depth or from side to side. The film stages several scenes in depth, as when the dishonest medicine-show men who will eventually steal the money arrive to try to get a permit to perform in town. As they arrive, Harold is seen in depth, wearing his father’s hat and badge, thus setting up the idea that they will believe that he is actually the sheriff. A more extended example occurs later, when he meets and is attracted to Mary, he climbs a tree to call after her as she leaves him, disappearing again and again behind a hill in the distance, and reappearing each time he climbs higher.

Lloyd skillfully employed shallow space equally well. When the medicine-wagon is destroyed by fire, Harold invites Mary to spend the night at his house. A disapproving neighbor lady soon takes her away, and Harold sleeps on the couch he had made up for Mary, complete with a tablecloth hung to give her privacy. Believing Mary still to be in bed, the two brothers separately sneak in to court her by primly handing her breakfast and gifts around the edge of the cloth. A shot from the other side shows Harold pretending to be Mary and enjoying being served food by the brothers when it is usually he who does the cooking.

Like The General, The Kid Brother demonstrates the sophistication that the great silent comedians had achieved by the late silent period.

As with the Lloyd films included in previous lists, The Kid Brother was released in the 2005 New Line boxed set, “The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection,” now out of print and available only from third-party sellers. Sold separately, Volume 2 is still in print; it contains The Kid Brother and The Freshman, as well as other important Lloyd films. Volume 3 is still available new from third-party sellers. Volume 1 is available from third-party sellers, mainly in used (and higher-priced copies).

Hollywood, serious

The popular impression seems to be that the gangster genre originated in the early sound period. Wikipedia’s entry on the subject treats Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) as the first gangster films. There had been occasional silent films that could fit into that category, notably The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912, D. W. Griffith) and Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915, Maurice Tourneur). In 1927, however, Josef von Sternberg made Underworld, which basically defined the genre that would soon become more prominent.

It has the gangster’s little mannerism, with “Bull” Weed bending coins to show off his strength (possibly the source of the cliché of the gangster flipping a coin). There’s the emblematic and ironic death, as when Bull’s nemesis “Buck” Mulligan is shot and falls at the foot of a cross-shaped memorial arrangement of flowers in the shop he uses as a front. There’s the thug with a heart of gold redeemed by the loyalty of a friend.

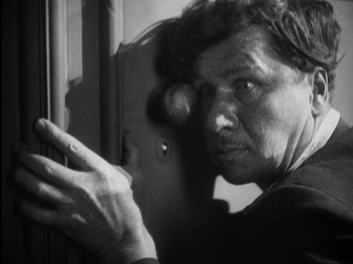

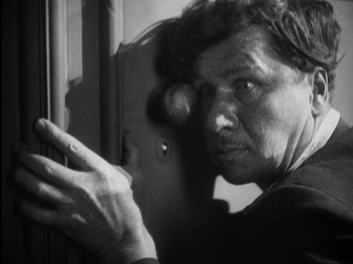

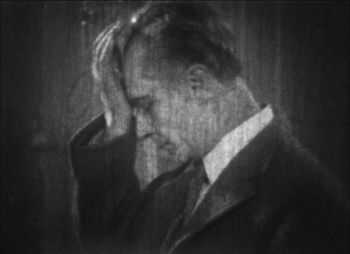

Von Sternberg is most often associated with Marlene Dietrich, whom he directed in seven films in the 1930s. He built three of his last four films of the late 1920s, however, around the burly star George Bancroft (below left). (We will encounter the second in next year’s list.) He’s also associated with beautiful design and cinematography, and the look of Underworld often anticipates the films noir of the 1930s (above, top, and below right).

I’ve already written about Underworld in greater detail than I have room for here–with additional pretty pictures. That was on the occasion of Criterion’s release of a set containing von Sternberg’s last three silents. Still indispensable but out of print and selling for high prices when you can find it. (Time for a Blu-ray?)

Late in her life, I asked my mother (born in 1922) what the earliest film she could remember seeing was. She replied that she couldn’t give me the title but recalled an image: a woman floating on a lake supported by reeds. I was quite astonished, partly because of all possible late 1920s films she had mentioned one which I could identify instantly from that brief description and partly because her memory had retained an impression of one of the great classics of the silent cinema. Living on a farm in Ohio, my mother probably saw it in a late run and so probably was six or seven at the time.

The presence of Sunrise on this list will hardly come as a surprise to anyone. Murnau has been a regular, appearing in our 1922, 1924, 1925, and 1926 entries. His first Hollywood film was thoroughly Murnauesque in style. It’s story of village versus country with a lingering touch of Expressionism in the rural scenes (below left) and modern design on ample display in the city (below right). The action could be set equally plausibly in Germany or the USA, except for the English-language signs in the city.

The plot is simplicity itself, with none of the characters even given a name. A Man is seduced by a Woman from the City, who convinces him to drown his Wife “accidentally” and flee with her to the gaiety of urban life. He nearly pushes his Wife into the lake while rowing across to the mainland but relents and tries to gain her forgiveness. This all occupies less than half the film, and most of the rest consists of the couple going forlornly to the city, with the Wife heartsick and the Man pathetically trying to reassure her. Once they reconcile, there is a long stretch of them having a good time in the city before heading home.

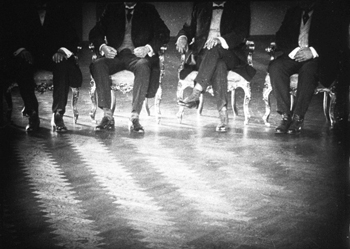

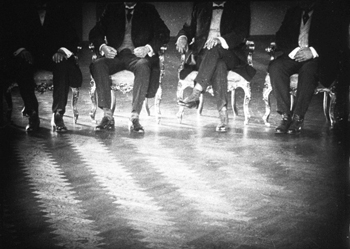

Yes, a good time. One might expect the city to be a hotbed of decadence that contrasts with their virtuous country life, but apart from an aggressively flirtatious gentleman, most of the people they meet are kind to them. A friendly photographer thinks they are a newly married couple and takes their portrait, sophisticated patrons at the dance-hall appreciate their performance of a country dance (below), and so on.

This meandering little set of unconnected vignettes does not conform to the Hollywood ideal. It presumably aims to guarantee that we believe in the husband’s redemption and the couple’s future happiness after their symbolic “re-marriage.” It holds our attention partly because of the charm of the two lead actors, George O’Brien and Janet Gaynor, and partly because the visual style always gives us something to look at. Murnau uses his “unfastened” German-style camera movements, not only in the famous track to the marsh early on but in a movement over diners’ heads accomplished by placing a camera on a support suspended from a track on the ceiling. (This technique was being widely adopted in Hollywood during the second half of the 1920s.)

Plus there’s that memorable scene of the Wife drifting on the lake, supported by reeds.

Sunrise is available in the elaborate 2008 12-disc boxed-set “Murnau, Borzage and Fox,” though the print is the usual soft, rather dark one available elsewhere. (The main gems of the box are the rare Borzage silents, including Lazybones, one of my 1925 picks.) Eureka! put out an edition of Sunrise as the first entry in its “Masters of Cinema” series. It contains not only the same print but a second print, a Czech release with distinctly better visual quality. (The image of the restaurant directly above was taken from it, while the others are from the “Fox Box.” I have not made a comparison between the two, but apparently the Czech version has significant differences from the American one.) This edition is out of print. Eureka! now offers the same two prints and supplements as a DVD/Blu-ray combination. Note that (despite what the Amazon.uk page says), this is a region 2 DVD and region B Blu-ray; both would require a multi-standard player in the USA and other regions.

The same “Fox Box” set contains Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, one of his best-loved films. By rights it should not be a great film. It is intensely sentimental, depends on huge coincidences, and has a thoroughly implausible ending, not to mention a saccharine religious theme that runs through it. Yet somehow it manages to be the greatest hypersentimental, coincidence-ridden, implausible, pious film ever. I cannot explain how or why.

Borzage’s film looks a lot like Sunrise, and it is often assumed that the resemblance arises from a straightforward influence of Murnau upon Borzage (e.g., his Wikipedia entry states that Borzage was “Absorbing visual influences from the German director F. W. Murnau, who was also resident at Fox at this time”), even though 7th Heaven was released four months earlier. There is something more complex at work here. The two films’ resemblances are not surprising, since German films had been drawing excited attention among American filmmakers for the past two years or so. The Last Laugh wasn’t a popular success, but its US distributor, Universal, showed it privately for cinematographers and others in the industry interested in studying it. Variety had been a hit. Its techniques of false perspective in sets and cameras moving freely through space soon caught on. For example, the sordid flat that the heroine Diane shares with her sister in 7th Heaven has a rough wooden floor sloping up toward the back (left). A similarly sloping floor appears in the bedroom in Sunrise (right)

German producer Erich Pommer’s first American film, Hotel Imperial (released by Paramount at the beginning of 1927), used a camera elevator, hanging sometimes from a track in the ceiling and sometimes from an improvised support on a dolly (see here for an image of it attached to the latter). The famous vertical elevator shot in 7th Heaven, following Chico and Diane as they ascend to his garret apartment at the top of the building was probably the most flamboyant use of the unfastened camera to that point. Below, in a later shot, the camera follows Chico back down as he goes to fetch water.

German style alone does not explain the film’s status as a great classic, though the slightly exotic look perhaps helped to make the garret romantic enough to be called “heaven” by its inhabitants as they fall in love. As with Sunrise, the Germanic look lends a certain fairy-tale quality that helps smooth over the plausibility issues.

Beyond this, there is again the charisma of the main actors. Janet Gaynor (who was in two of this year’s greatest films) and Charles Farrell (a slightly awkward but appealing actor) became the ideal couple of the late 1920s, co-starring eleven more times between 1927 and 1934. Equally, there is the ineffable directorial sincerity that comes across in Borzage’s best films, a trait often summarized as “romantic” or “naive.”

Unfortunately the print of 7th Heaven in the “Fox Box” is virtually unwatchable. Apparently the French DVD is from a better source than the Fox release; this DVD may be the source of a version which has been posted on YouTube with bright yellow Greek subtitles. The two frames above were extracted from that online copy. Another film calling out for restoration.

Germany: farewell to Expressionism

Expressionism probably would have ended in Germany in 1926, with the releases of Murnau’s Faust and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Both films went over budget and schedule, with Lang’s being late enough to be released on January 10, 1927. Both films contributed to the decline of the large production company, UFA, which had to rely on loans from Hollywood to keep going. Murnau was by this point in America, and he never worked again in Germany. Lang had to produce his next film, Spione (destined for our 1928 list), himself, and he opted for a more streamlined modern look.

Metropolis mixes Expressionism with the sets representing the futuristic science-fiction city. The pleasure garden of the wealthiest class (above), as well as the catacombs and chapel of Maria far under the city are Expressionist, and even in the city sets the crowds often move in the choreographed fashion typical of the style.

Expressionism remained thereafter as a minor stylistic option. (Alexandre Volkoff’s 1928 French-German co-production Geheimnisse des Orients used Expressionist sets to create a fairy-tale Middle-East, rather like The Thief of Bagdad [1924].)

Metropolis has received so much attention that there is no need to plug it again as a great classic. In fact, it has been hyped to the point of being over-valued. Any of Lang’s other films from 1922 to 1928 is arguably better. It has a mawkish main premise (the heart must mediate between head and hands in labor disputes) and plot flaws (why would Fredersen destroy the substructure of his city when his power and dominance depend on maintaining it?), neither of which is a problem in Lang’s other films of this period. It deserves to be called a masterpiece for its audacity of vision, technical innovation, and many great moments.

Fans of the film will be aware that the long-lost scenes of the film were discovered in South America and restored to the film, rendering it nearly complete (running 148 minutes in Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray release). The recovered footage was unfortunately in very worn condition, and restoration can only do so much. The film is, however, much improved by having it.

David has already written on the strengths and weakness of this “great sacred monster of the cinema,” including a discussion of how the restored footage enhances it.

Back in 1970, when I was an undergraduate and first dipping a toe into film studies, G. W. Pabst was considered one of the major figures of German cinema, close to if not quite as great as Lang or Murnau. In my first film course the incomplete version of The Joyless Street was shown. (I liked it much better when it was restored.) I saw The Love of Jeanne Ney shortly thereafter. By now, however, The Joyless Street and Pandora’s Box have become the Pabst classics upon which his reputation is largely based. Whether Jeanne Ney‘s gradual fall into relative obscurity is the cause or the effect of its being difficult to see is hard to say. (I could only find it as a 2001 DVD by Kino, so-so but acceptable in quality.) Either way it’s a pity, since it deserves to be better known.

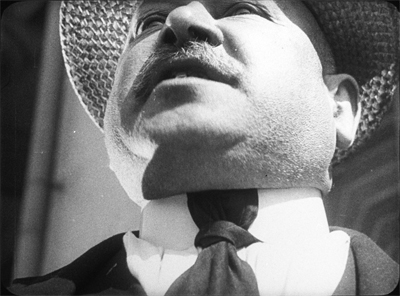

An adaptation of Ilya Ehrenburg’s novel of the same name, Jeanne Ney is set in the Civil War period that followed the Russian Revolution of 1917. The story begins in the Crimea, where Jeanne’s anti-Bolshevik father is a political observer. During the capture of the town by the Red forces, Jeanne’s lover, Labov, kills her father in self-defense. She forgives him and flees to Paris. Jeanne gets a job as a secretary in her miserly uncle’s detective agency, primarily to be a companion to her blind cousin. (Gabriele is played by Brigitte Helm, who was also Maria in Metropolis, thus making her our second actress appearing in two of this year’s top ten films.) A rascally opportunist, Khalibiev (played with sleazy relish by Fritz Rasp, see bottom) tries to marry Gabriele for her money, even though he actually lusts after Jeanne. Killing and robbing the uncle, he pins the murder on Labov.

Stylistically the film is a fascinating mix typical of the late 1920s, when influences were passing rapidly among European countries. It strives for a certain degree of the realism characteristic of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement that Pabst had helped to establish with The Joyless Street. The first part is influenced by the Soviet films that had become popular in Germany only the year before, and the Crimea-set portion could pass for a Soviet film, though not one of the more daring ones. The execution scene (below left), with the rifles sticking into the frame dramatically, was already calling upon a composition typical of the Montage movement. The interrogation of Jeanne takes place in a cluttered headquarters just set up by the conquering Reds (complete with authentic costumes and “typage” casting); the framing emphasizes both Bolshevik ideals and realism, placing in the foreground a soldier trying to make tea.

For the longer Parisian portion of the film, Pabst shot on location, as the French Impressionists were doing. He mixed this sense of realism (below left) with subjective scenes, including Jeanne’s superimposed vision of her wrongly-accused lover being executed. The film has one great set-piece, the cousin’s gradual discovery of her father’s murder as Khalibiev stands watching, thoroughly spooked by her blind staring face (below right).

Time to bring this film back into the canon.

Much more familiar is Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, with which Walter Ruttmann brought the city symphony into the mainstream and solidified a growing strain of realism in German cinema. There had been short films and features that wove together visual motifs from urban life (e.g., Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta, 1921), mostly captured on the fly though occasionally staged.

Ruttmann has been mentioned on previous ten-best lists for his abstract animation. Berlin begins with some moving abstract shapes that gradually give way to a train journey. During this real objects create abstract patterns, as when the girders of a bridge create a flicker effect as they flash by (below left).

The journey ends in a major station in the city. From there on, Ruttmann cuts together scenes to create what was to become a familiar city-symphony time-frame, a day in the life of a metropolis. Empty, silent streets lead to an early-morning dog-walker (above right) and then the bustle of the workday, lunch, and finally nightlife.

To this point most experimental films had been short and either abstract or surrealist. That experimentation could emerge from the documentary mode was a new concept, and Berlin, though it may not seem very radical to us today, helped to establish this new approach. The fact that it was co-produced by Fox Europa gave it distribution in mainstream theaters, and it has had a great influence on subsequent filmmaking, right up to the present. Coincidentally, that influence is demonstrated by the recent release of Alex Barratt’s London Symphony: A Poetic Journey through the Life of a City (2017). Flicker Alley’s liner notes include:

The release of this Blu-ray coincides with the 90th anniversary of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927), one of the most important examples of the original city symphonies. Ruttmann was one of the great pioneers of experimental film, and Barrett and [James] McWilliam [composer] have worked hard to bring a similar sense of poetic playfulness to London Symphony, while also updating the form for the 21st Century.

Berlin is available in several DVD editions, but the definitive one is in a two-disc set including Ruttmann’s Die Melodie der Welt, the first German sound film, both in restored versions from the Filmmuseum series, as well as Ruttmann’s short abstract films. I note that this is available on Amazon in the USA, but be aware that it’s PAL and so requires a multi-standard player.

The essence of French Impressionism in 38 minutes

I know most readers will expect a much, much longer French film about Napoléon to be in this spot, but I’m opting for Jean Epstein’s modest but brilliant short feature, La Glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”). Perhaps no other film of the Impressionist movement managed to create a plot that combines the subjective techniques that delve into character psychology with the presentation of events through fleeting impressions rather than linear causality. Most Impressionist films today seem a bit old-fashioned, adhering to the modernism of the era. La Glace seems familiar to aficionados of Resnais or Antonioni.

Epstein divides his brief tale of his protagonist, an unnamed playboy, into three parts devoted to the women–a wealthy society woman, a modern sculptor, and a modest working-class woman–who are all having affairs with him at the same time. Each tells her tale of his callousness and neglect to a sympathetic listener, and each presents a very different view of him. Intercut with their stories are scenes of the protagonist taking a solo ride in his sports car (above), speeding through the countryside and stopping at a local fair. Throughout he seems happier than he had with any of his lovers.

The individual scenes are brief, with quick cutting presenting glances and gestures, often from angles that prevent our getting a good look at what is happening, as with this moment in a restaurant.

We grasp what is going on primarily because the events are extremely simple. In each case the protagonist is with one of the women and abruptly walks out on her. The third tale, told by the working-class Lucie, is cut together in nearly random chronological order and with parts of the action missing. Lucie has prepared a romantic dinner at her home, but the man arrives, greets her, looks over the table, and leaves. In this snippet, however, his looking over the table is followed immediately by a shot of him just after his arrival, as Lucie embraces him and removes his hat.

The narrative achieves closure, but the film ends with an emblematic shot of the hero superimposed over a three-sided mirror, emphasizing the differences in the three women’s perceptions of him. La Glace à trois faces goes perhaps as far as any silent film does in using challenging modernist tactics, frustrating the viewer with a lack of clarity about causes and traits. It was a new form of narration that had little immediate impact on the cinema. The film was barely seen at the time. It would not be until decades later that similar techniques became common.

La Glace is available in the boxed-set of several of Epstein’s films, which I described and linked here. It is also included in Kino’s “Avant Garde” set on the 1920s and 1930s.

Tracing the birth of a Bolshevik

One can see why the Soviet government liked Pudovkin best among the major Montage directors. His films, while employing the fast cutting, dynamic angles, and other stylistic traits of the movement, are fairly straightforward and comprehensible compared to, say, Eisenstein’s pyrotechnics in October.

While the latter concentrates on the events of the Revolution proper, with no single character singled out for us to identify with, Pudovkin works up to the Revolution by following the radicalization of a peasant. The unnamed “Village Lad” sets out from his impoverished rural home to find work at a factory in the big city. We see the fomenting of a strike over dangerous working conditions and extended work hours, which begins as the Lad arrives. Ignorant of politics and the class struggle, he seizes his chance to join the scabs replacing the workers. Even worse, he betrays some of the strike’s leaders to police.

The story moves away from the Lad, who really is not very prominent in the narrative and is never characterized enough to gain much sympathy. As World War I begins, the film focuses on stock-market manipulation and war profiteering. Using typical typage casting, Pudovkin caricatures the capitalists as fat cats out for themselves (above). Eventually we see the Lad again, now wiser in the ways of the world and ready to serve the Bolshevik cause. By the end, the Reds attack the Winter Palace in a suspenseful scene, though one much shorter than the one in October.

Pudovkin featured on our list last year, for his best-known film, Mother. There the hero and his mother gain a good deal more sympathy than the Lad does, and The End of St. Petersburg is as a result perhaps a less entertaining film than Mother. Still, it is a masterly film and one of the gems of Soviet Montage.

While rewatching End on DVD, I realized that the main editions available used the same version of the film, a sonorized “restoration” done by Mosfilm in 1969. What other changes might have been made are not apparent (some films “restored” in that period were recut), but the images are severely cropped. The left side of the frame is missing, more than what one would expect would be necessary to add a sound track. The top and bottom, too, are missing portions. Only the right edge seems more or less intact.

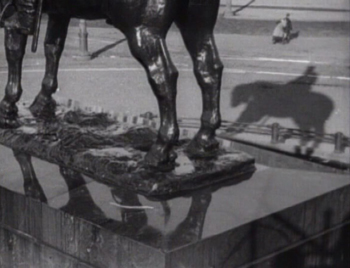

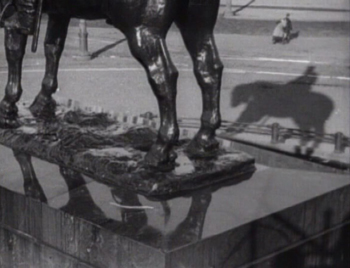

Take this famous image. The film has set up a motif of statues that come to stand for the imperial-era city. At one point there is a depth shot past an equestrian statue looming in the foreground while the Lad and his companion are seen as tiny figures walking across the square in the background. Compare the DVD image with one taken from an archival 35mm print.

This is bad enough, but when Pudovkin starts using the edges of the frame to make ideological points, the result nearly negates the his meaning. A famous shot shows a row of seated military officials with their heads offscreen. The 35mm image cuts them off precisely at the collar. The DVD print goes down to mid-chest, while losing much of the fourth man on the left. One might say that the same simple metaphor is being presented, but it’s not as instantly apparent what Pudovkin is implying here.

So while I recommend this film, I have to caution readers that it is not currently easy to see it in an acceptable print. An older 16mm copy or a 35mm screening in an archive would be ideal but not accessible to very many. If you want to see it, even in this faulty version, the Image and Kino releases both contain the Mosfilm print. The Image DVD has End paired with Pudovkin’s very worthwhile first sound film, Deserter (1933). Since it was a sound film to begin with, Deserter is not significantly cropped here and is quite good visually. Unfortunately this version is long out of print. The Kino DVD includes Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930) and Pudovkin’s short comedy Chess Fever (1925). It is available for sale and streaming on Amazon. Perhaps our friends at one of the home-video companies dedicated to putting out restorations on DVD and Blu-ray might consider tackling this key title.

For readers who prefer streaming, The Kid Brother, Sunrise, and Metropolis are currently available at FilmStruck on The Criterion Channel. Underworld, The General, The Love of Jeanne Ney, Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, La Glace à trois faces, and The End of St. Petersburg are held in MUBI‘s library, but none is currently playing there. We haven’t checked any of these versions.

Flicker Alley’s London Symphony is available for streaming here and on MOD Blu-ray.

Our colleague Vance Kepley has written a book in the Taurus Film Companion series on The End of St. Petersburg. It seems to be slipping out of availability on amazon.com, can still be had at amazon.co.uk, and is available directly from the publisher. Malcolm Turvey discusses some of the films on our list in his The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s.

December 28, 2017: Our thanks to Manfred Polak, who sends some good news about a restoration and possible upcoming availability of one of our films: “A restored version of “The Love of Jeanne Ney” was shown in an open-air event in Berlin last August. This version also aired on German-French TV station Arte, and it was available for legal download and streaming in HD for three months. I think there might be a DVD or Blu-ray of this version in a few months.”

The Love of Jeanne Ney

Posted in Actors: Lloyd, Directors: Borzage, Directors: Keaton, Directors: Lang, Directors: Lloyd, Harold, Directors: Murnau, Experimental film, Film history, Silent film, The Ten Best Films of... |  open printable version

| Comments Off on The ten best films of … 1927 open printable version

| Comments Off on The ten best films of … 1927

Tuesday | December 19, 2017

DB here:

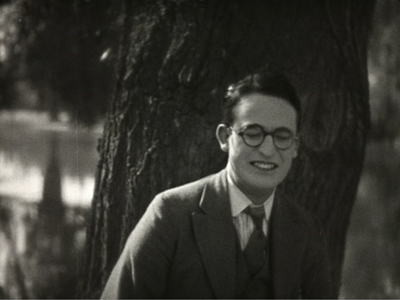

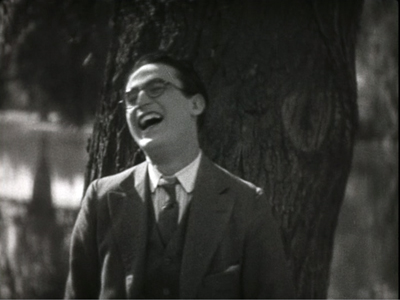

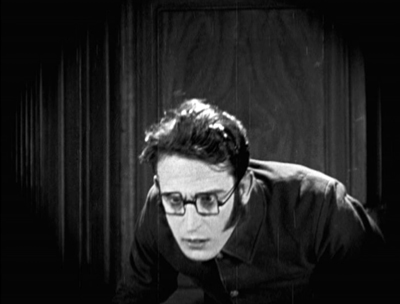

On 9 September 1917, film history changed for the better. That was when we got the eyeglasses.

Their circular, horn-rimmed frames stood out as wire rims would not; besides, horn rims had become fashionable for young people. These specs held no lenses, but so much the better. Reflections from studio lights would have hidden the eyes of the winsome, earnest, clueless young man usually called the Boy.

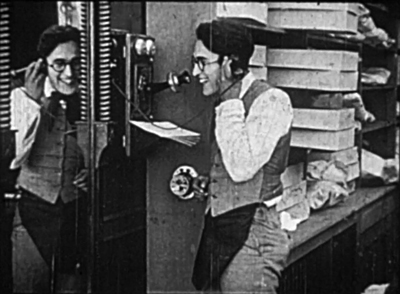

In Over the Fence, the film introducing him, he’s already amiable, a little vacuous but delighted to be talking to his girl on the phone and watching himself doing it.

Harold Lloyd had already featured in some sixty-five short comedies from 1915, playing characters called Willie Work and Lonesome Luke. Even after introducing the Boy, Lloyd continued with a few Lukes before phasing out this sad sack. No one expected that in a few years the glasses character would become world famous. Lloyd’s films were more lucrative in aggregate than those of any other silent comedian, and he became one of the central figures in Hollywood.

When our comrades at Criterion announced their plan for a centenary Lloyd celebration this month on FilmStruck, I suggested we devote an installment of our series to one of the films. Kristin and I have been Lloyd fans for decades. Fans and collectors kept his work alive. Kevin Brownlow had to remind people with his Lloyd documentary, The Third Genius (1989), that, well, Lloyd was a genius. The more you get to know his work, the better it looks, and the less plausible seem many of the clichés that have clustered around it.

One of the very best films to get to know is Girl Shy (1924). That’s the one analyzed in the latest Observations on Film Art episode on the Criterion Channel.

Man into Boy

For decades after sound came in, American silent comedies dropped mostly out of sight. Some 16mm copies were available in cut-down rental versions, and a few were circulated by the Museum of Modern Art Film Library. (Of Lloyd’s work, that included only The Freshman of 1925.) The MoMA canon became the canon. In the 1970s, thanks largely to piracy, the films of Keaton were added, and still later we came to recognize Charley Chase, Max Davidson, and other talents.

Throughout these years Lloyd’s films were almost invisible because he controlled the rights to them and limited their circulation. Kept in vaults in his rococo estate Greenacres, they would not reemerge until the 1960s, in cut TV versions distributed by Time-Life. Until fairly recently, most critics relied on memory of the films and the received image of the Boy dangling helplessly from the clock face.

Most of the sixty-one shorts featuring the Boy languish in archives, and some were lost in a fire on the Lloyd estate. But several two-reelers are readily available, as are all the longer films. What we have gives the lie to most clichés about this filmmaker.

Take the most persistent one. Socially conscious critics of the 1930s saw Lloyd’s work as naively reflecting the go-go 1920s. The Boy’s resolutely middle-class aspirations made him a crass avatar of complacency before the Crash. Chaplin seemed to stick up for the little guy, but Lloyd seemed to celebrate the striver; he compared himself to Tom Sawyer. It was all very neat. The Boy’s climb up the skyscraper in Safety Last could symbolize the heedless ambition of the white-collar worker, while the his efforts to fit in at college in The Freshman suggest desperate American conformity.

Those interpretations played down the fact that just as often Lloyd played hayseeds humiliated by city folk and con artists. In Girl Shy, the city slicker who wants the girl is a weasel, and Harold has to rescue her. Here, as often, the film is largely a procession of social humiliations. Lloyd, a predecessor of cringe comedy, in turn provided a model of embarrassment for Ozu’s silent films. Those films often feature students wearing the Boy’s glasses (below, Days of Youth, 1929). This isn’t mere imitation or homage; the glasses became a Japanese fashion item, called roydo, named after Lloyd. (Below, a photo from a student ski trip in the 1930s.)

More edgily, Lloyd also played foppish idlers, louche one-percenters who glide obliviously through the lower orders and need to learn humility. The original title of For Heaven’s Sake (1926) was to be The Man with a Mansion and the Miss with a Mission, a phrase retained in an intertitle. Here as elsewhere, the coddled Boy learns to help his social inferiors. If you’re after class-based critique, Lloyd films come out pretty well.

Likewise, there were the complaints that Lloyd’s comedy was mechanical. Chaplin was the poet and dancer. Keaton, in both concept and execution, showed himself a geometer, the dogged engineer of monumental effects more awe-inspiring than hilarious. Though granting that Lloyd, foot for foot, yielded more laughs than any of his peers, critics worried that he was only merely funny, a relentless gag machine. Here is James Agee, in one of the subtlest appreciations of silent cinema ever written:

If great comedy must involve something beyond laughter, Lloyd was not a great comedian.

But immediately, as an honest man, Agee must add:

If plain laughter is any criterion—and it is a healthy counterbalance to the other—few people have equaled him, and nobody has ever beaten him.

Still, Agee admits that Lloyd’s films pass beyond laughter in one respect. They offer harrowing suspense. What his audiences called “thrill comedy” remains chilling today. His antics on skyscraper ledges and girders still induce vertigo, and his car chases risk catastrophe on a scale that would worry Jackie Chan. Agee seems to grant that inducing shrieks as well as guffaws is no small accomplishment.

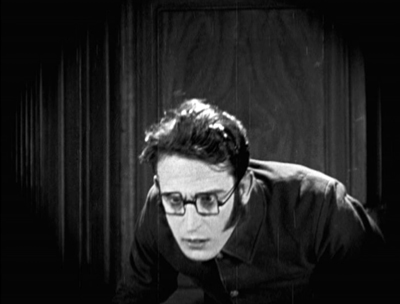

If Agee could have reviewed all the feature films, though, maybe his judgment wouldn’t have been so absolute. For example, Lloyd’s features take us beyond laughter in serious ways—into regions of vulnerability and inadequacy. The Boy is typically given a fault: cowardice (Grandma’s Boy), self-absorption (as hypochondria in Why Worry? and as self-indulgence in For Heaven’s Sake), lack of confidence (The Kid Brother), neurotic extroversion (The Freshman). In several films, the seriousness undercuts the comedy.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold can’t drive away the tramp, but Granny can do it easily, with some swipes of her broom. Our laughter is cut short when, in the space of a cut, as she calmly returns to the porch, we see the Boy slumped over, his head in his hands.

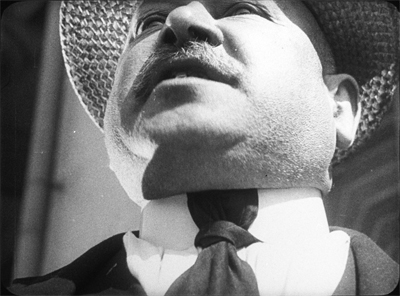

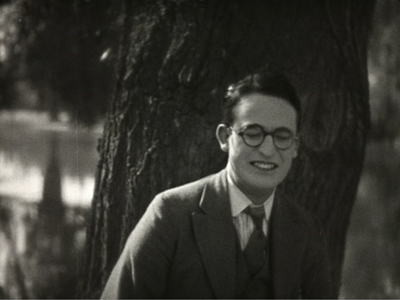

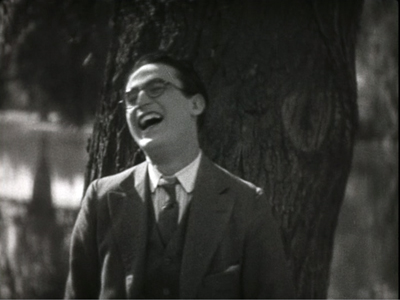

Soon he will admit that he’s a coward. Lloyd films switch their tone on a dime, shifting between comedy and drama breathlessly. In Girl Shy, the Boy not only dumps the girl he loves but does so by cruelly laughing at her trust in him. (Agee: “He had an expertly expressive body and even more expressive teeth.”) Wobbling and shifting his weight, Harold breaks the laugh with a gulp before carrying on his bluff.

Nothing in Keaton or Chaplin makes us as ashamed of our hero as we are right now. Soon he will do something worse.

This passage reminds us that Lloyd worked his face for all it was worth. Keaton had more expressions than he’s usually credited with (bewilderment, concentration, doggedness); it’s just that he doesn’t smile. Chaplin inherited the white-face clown tradition and often favored deadpan. He limited his facial reactions to squiggles and flashes, often no more than a skew of the mouth or hauteur in the brows, with an occasional embarrassed giggle. With Chaplin, the body expresses nearly everything, as befits an aesthetic predicated on the long shot.

But Lloyd, relying on medium shots, performs as a dramatic actor, with a wide repertory of expressions. Agee refers to his “thesaurus of smiles,” but he had other resources, as this Girl Shy scene attests. His producer Hal Roach is said to have remarked: “Harold Lloyd was not a comedian. But he was the finest actor to play a comedian that I ever saw.”

Another nuance: Comic laughter comes in many varieties. Like Keaton, Lloyd celebrates winning through tenacity and resilience. If we gasp at the geometrical audacity of Keaton’s humor, we’re buoyed by Harold’s righteous settling of accounts. It’s reported that audiences actually leaped up and cheered at the climaxes, when bullies and rascals were punished at delectable length. These are comedies of comeuppance and payback, outcomes universally enjoyed and still much in demand today, when millions hope for a scourging of the jackals in our White House.

Point the last: Neatness of construction. Chaplin’s films are lovably episodic; I still marvel that films that took so long to make are so loosely put together. Keaton by contrast is a metronome-and-protractor director, aiming to make every shot and sequence and reel sit in meticulous order. No one but he could have conceived the marvel of symmetry that is The General, or, on a lesser scale, Our Hospitality and Neighbors.

Lloyd’s films are no less finely put together, as many recognized at the time. A Film Daily review of The Kid Brother (1927) noted: “Lloyd and his gag-men again have devised a corking set of comedy situations that fit consistently into a well-joined plot and laughs keep building from little chuckles to hilarious roars.” Orson Welles praised “the construction of Safety Last, for instance. As a piece of comic architecture, it’s impeccable. Feydeau never topped it for sheer construction.”

To get a little more specific, I think that Lloyd’s model was the well-made dramatic film, the tight classical plot. This is the argument I make in the Girl Shy installment. I try to show that in this, his first film as an independent producer, Lloyd applied the emerging model of Hollywood narrative to feature-length physical comedy. Fairbanks had moved in this direction, and Lubitsch would achieve something similar with social comedy in The Marriage Circle (1924) and the masterpiece that is Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

Lloyd was a pioneer in showing how everything that worked for serious dramaturgy could work for comedy too. Girl Shy gives us a goal-oriented protagonist who has a serious flaw. Going beyond the figures of slapstick, we get access to his psychological yearnings and frustrations. His loneliness and fear of women fuel overwrought fantasies of domination. The Boy is caught up in the characteristic Hollywood double plot, involving love and career—two lines of action that usually block and deflect one another.

This linear action is deepened by a series of motifs. They’re simple in themselves (a stammer, a Cracker Jack box, a dog biscuit box), but they’re worked out with a pictorial and dramatic intricacy that’s rare at the time. And it’s all topped off by a two-reel chase that is simply one of the greatest ever put on the screen. At a time when every superhero blockbuster ends with a big action sequence, it’s worth seeing one that’s both graceful and hilarious, and it owes nothing to special effects.

Girl Shy shows how rewardingly complex silent Hollywood storytelling could be. It reveals Lloyd as a master craftsman of cinematic resources—dramatic, pictorial, emotional. He saw how to make a movie that would be engrossing even without the gags. The comedy deepens a powerful dramatic premise that moves forward with an organic, not mechanical, energy, and it’s developed in funny or poignant detail at every instant.

Filling the format

In the arts, form often follows format. The fourteen-line sonnet, the tondo painting, the twenty-two-minute sitcom, the nine-panel comic-book page: all provide the artist with a set framework within which to create. When Lloyd started out, film reels in the US were standardized at 1000 feet, which typically ran between twelve and fifteen minutes, depending on projection speed. Short films, particularly comedies, were either one or two reels, while features–dramas, mostly–ran four, five, or more.

The task of the filmmaker was to build a story that would fit the format. The temptation was padding. Griffith, for instance, often filled out his shorts with “goings and comings,” shots of characters leaving one place and making their way to another, sometimes across several shots. But once padding was inserted, filmmakers could make it engaging. Griffith did this by embedding the goings and comings in suspenseful situations, so that the travel shots served as dramatic delays. Mack Sennett needed scenes to lead up to a big chase (the “rally”), but those scenes could themselves have a linear logic, as with romantic rivalry or street quarrels.

Lloyd became very sensitive to film length. He knew that his initial popularity depended on the fact that Pathé and producer Hal Roach spit out a Lonesome Luke every week or two; he saturated the market. Even after Luke appeared in two-reelers, Lloyd wanted his new character, the Boy, to start in one-reelers. He recalled telling Roach, in sentences as breathless as the pace of a one-reeler:

Now, I’m getting started in a new character and you want people to get used to the character, you want them to see the character; and besides, if you make a poor, or mediocre, or moderately good, or even a bad picture in a two-reeler, it’ll kind of tend to sour the people on you because they won’t see another one for a month. But if I make one-reelers, we’ll get one out every week, so if a couple of them are not so good, and the third one is, it will cover up the other two, and besides it will keep you in front of the public.

As a result, Lloyd spent two years turning out an astonishing eighty-two one-reelers. Not until Bumping into Broadway (2 November 1919) did he launch a two-reeler featuring the Boy.

There’s evidence that Lloyd’s awareness of the niceties of running times went beyond a concern for building the brand. He understood that form and format had to mesh. His early one-reelers relied largely on the standard episodic knockabout. We’re given a defined situation, such as a modernized hotel (The City Slicker, 1918), a western saloon (Two-Gun Gussie, 1918), or a vaudeville theatre (Ring Up the Curtain, 1919). In this situation, the characters quarrel, pull pranks on one another, engage in fistfights, kick each other in the pants, and usually wind up in a chase. A string of gags might emerge, as when a stray snake terrifies the theatre troupe in Ring Up the Curtain, but the gag is quickly exhausted, and we go on to the next bit.

Once Lloyd settled on two-reelers, he built them up more carefully. He scaled, we might say, his plots and gags to a fairly tight, logical development in the fuller format. Part of that development involves what we might call nested gags. In Captain Kidd’s Kids (1920), the first part (roughly one reel) sets up Harold as a playboy recovering from a bachelor party. In his elaborate bathroom, he tips back his chair, leading us to expect him to fall in. But no: instead his butler, Snub Pollard, dumps ice in the pool.

There follows a string of shaving gags here and in the next room. Early in this series, Harold drips shaving cream in his morning tea; but after other gags he comes to drink it and finds it foul-tasting. Then he returns to the bathroom, tips back the chair again, with results we’d expected several minutes before.

Now we get some elaborate efforts to rescue Snub. The gags are simple, but by setting up one and then moving to set up and pay off others before returning to the first, Lloyd and his team avoid the start-stop-restart pattern than we find in many one-reelers.

The real plot action, of course, doesn’t get going until the second reel of Captain Kidd’s Kids, but Lloyd has provided some lively padding to start. Now or Never (1921) shows the same gag-braiding, with the recurring appearance of two drunks on the train ride that constitutes the bulk of the film.

Lloyd moved toward longer films cautiously—first to three reels, then four (A Sailor-Made Man, 1921), then five (Grandma’s Boy and Dr. Jack, 1922). He always said that most grew organically, beginning as two-reelers and then expanding when the story premises and gag sequences developed. To keep things in proportion, he tested the results on preview audiences, then reshot and recut his footage. The preview responses to one three-reeler, I Do (1921), convinced him to lop off the entire first reel. Although he had increased confidence in his ability to scale up, when he signed a new contract with Pathé in early 1922 he insisted that the company publish a notice to exhibitors declaring that film length would be

strictly governed by the character and quality of the material evolved in the production development of each subject—which means that the Lloyd standard of excellence is to be maintained first of all; a given story that turns out to be adequately filmed in two reels will be confined to two reels, and so released. This is a principle cherished by Lloyd himself.

Lloyd could be so confident because even his shorter releases were becoming the top-billed item on programs across the country. He was, in effect, returning the idea of “feature” to its original meaning—not simply a long film, but rather a movie that could be “featured” in publicity. He was also announcing his unusual concern for tight form.

Comic architecture

Grandma’s Boy (1922).

Lloyd moved to features in synchronization with his peers. Keaton was the first, with The Saphead (September 1920), though it’s less a comedy than a light drama; and Keaton returned to making two-reelers for three years. The Round-Up (October 1920) gave Fatty Arbuckle a comic role in what was basically a serious drama. Arbuckle starred in The Life of the Party (December 1920), another light drama with almost no physical comedy. Chaplin’s The Kid (February 1921), at a bit more than five reels, might be considered the first slapstick feature since the one-off Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914, six reels). The émigré Max Linder got into the act with two 1921 features, Seven Years’ Bad Luck (May 1921) and Be My Wife (December).

It might seem that Lloyd was a bit late with the four-reel Sailor-Made Man (December 1921). But that film capped his most extraordinary year to date, with four earlier films released in spring, summer, and fall. Along with six two-reelers released in 1920, Lloyd was now a major comedy star, and the Boy could carry a longer story.

But how to do that? His peers explored some options. In Arbuckle’s two features, it’s his physical presence that matters, not consistency of character; in one he’s a genial sheriff, in the other a lawyer inclined toward crookedness. Chaplin retained the Tramp persona in The Kid, but the film is a rather episodic affair. Once the main plot is resolved, a reel pads out its length with a dream sequence set in heaven. The Linder films are lively but digressive, with plots propelled by casual pranks and lovers’ misunderstandings.

By contrast, Lloyd’s features moved toward tight construction. Despite his claim that his films just grew longer accidentally, they were shaped in ways that make them seem through-composed. His comedy sequences are deftly prolonged, building and topping themselves with great speed. Gags are embedded and interwoven in ways that yield surprises, and motifs set up early in the film pay off later. We may have forgotten about them, but Lloyd hasn’t.

Lloyd’s obsession with overall form can be seen in his use of the “Lafograf,” a kind of EKG of viewers’ response at previews. Coders sat in the audience with pencil, paper, and stop watches to note every bit of amusement, from a titter to a screech. Once graphed, the entire movie displayed laughs big and small throughout, with most of the big ones spiking in the last reel.

A powerful demonstration of Lloyd’s skill came in his first five-reeler, Grandma’s Boy (1922). Chaplin called it “one of the best constructed screenplays I have ever seen on the screen.” Lloyd began it as a two-reeler, but after expansion it had become more drama than comedy. Roach urged him to add more gags, and the result is a remarkable balance between humor and pathos.

That mixture is given from the start in a prologue showing a baby Harold, glasses and all, bullied by another baby. Then the Boy as a boy is picked on and made to put a chip on his shoulder.

This last bit will pay off fifty minutes later. The rival, the little bully grown up, taunts Harold, not knowing Harold has captured the prowling tramp and proven his courage.

The upshot is a fight that knocks the stuffing out of the Bully. In the course of that fight, another moment calls up a contrast with an earlier scene. The day before, the Bully has pitched Harold into the well; now, after the Rival tries a foul blow, Harold administers payback.

These distant echoes can be very satisfying.

The organization of gags is likewise remarkably sustained. Walking home from his well dunking, Harold finds that his one suit has shrunk grotesquely. But the Girl has invited Harold to her home for an evening, so he needs another suit. Granny digs out his Grandpa’s suit, 1862 vintage. (The peddler said it was unique.) It still has mothballs in it. Granny also finds there’s no shoe polish, so she uses goose grease instead. These bits become the basis of a steadily building gag situation in the Girl’s parlor.

But not right away. First Harold arrives and discovers that his vintage outfit is matched by that of the butler. Another echo, when he mutters: “That peddler lied to Granny!” He sits to listen to the Girl play the piano, and gets his finger caught in a vase. Only now does one of the earlier gag setups start to pay off. A cat comes to lick his tastily greased shoes.

The grown-up Bully was introduced throwing a stick at a cat, but Harold is more gentle. He nudges the Girl’s cat away, but soon a troupe of cats enters to converge at his feet.

He has to dispose of them without the Girl’s noticing. Finally, when the couple move to the settee, the cats reconnoiter and the gag sequence pays off: Harold uses a statuette of a bulldog to scare them away.

Cozying up to the Girl, Harold ought to be in clover, but now she smells something—his suit. Investigating, he finds mothballs that he and Granny failed to remove. I’ll spare you more description. You can watch what happens next, including a new confrontation with the Rival. And again, Harold gives us an unforgettable suite of facial expressions.

Lloyd’s pacing allows just enough time for us to anticipate what might happen at each turn of events. Structurally, while Lloyd is developing and paying off the IOU of the mothballs, he wedges in a fresh setup, that of the neighbor kid’s requesting some gasoline. That becomes the topper for the mothball series, as the dog statuette topped the cat gags. This sort of braiding of gags, weaving the setup of one gag into the development of another, shows how a feature can be built out of quasi-melodic lines, like a song.

Even more important is the presentation of the protagonist. Lloyd gives his hero what modern screenwriters call a character arc. In the early 1920s Lloyd began to distinguish between gag pictures and “character pictures,” in which the story line depends on our concern for the protagonist.

In his short films, Harold had an established image, but his characterization varied a lot. Sometimes he was a good-natured everyman, but he could also be a scrapper, a hustler, or a ne’er-do-well. And his romantic relations with Bebe Daniels were wonderfully flirtatious; in one she helps him count bills by licking his thumb. In the features, Harold was given a more definite character, one with a pronounced fault. He was often insecure, awkward, and oblivious, qualities that led critics to call him a boob. The insult is referenced in Girl Shy, when his book gets mocked as The Boob’s Diary. Correspondingly, the romance plotline of his films became much more fraught.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold’s fault is cowardice, and he must keep the Girl from finding it out. His impulse is to hide from the world, but Granny inspires him with the tale of how his Grandpa overcame his fears and helped the southern army win the war. He did it, she says, thanks to a Zuñi charm given him by an old woman.

Now Grandma gives Harold the charm, and his faith in it enables him to capture the murderous thief. In a double climax, Harold, still clinging to the charm, is able to beat the Bully in a drag-out fistfight.

Of course the action is packed with delays, detours, and surprises. The capture of the thief is a superb flow of gags, from Harold braving the tramp’s hideout to a long chase, in which the talisman does duty as a pistol barrel. And the fight with the Bully gets expanded when Harold loses the charm and turns suddenly meek. After the fight, the topper comes when Granny reveals the real source of the charm’s power. Harold comes to understand that he has inherent reserves of courage.

Nicholas Kazan once observed: “You want every character to learn something. . . . Hollywood is sustained on the illusion that human beings are capable of change.” This principle of construction goes very far back, and it became the basis of Lloyd’s feature plots. We get not just a change of fortune (and so a happy ending) but a change in personality (and so a happier one).

From Grandma’s Boy onward, Lloyd’s features display disciplined, inventive construction–at the macro-level of plot and at the mid-range of gag sequences, down to precise shot-by-shot articulation of the action. Here’s a moment when Grandpa (he wears glasses too) sees, reflected in an inkstand lid, a Union officer preparing to clobber him.

Since the Bully is reincarnated in the Union officer Harold outwits, this flashback quietly prefigures the Boy’s victory over the Bully at the climax.

In my Criterion Channel presentation, Girl Shy serves as another example of how Lloyd brought classical construction to comedy. I could as easily have picked another superb item, The Kid Brother. Maybe next year?

It seems likely that Lloyd’s work became a model. Keaton’s trimly carpentered second feature Our Hospitality (1923) is in the same vein. And Chaplin, after he praised Grandma’s Boy, went on to declare: “The boy has a fine understanding of light and shape, and that picture has given me a real artistic thrill and stimulated me to go ahead.” Lloyd and the Boy, glasses and all, remade Hollywood comedy in important ways, and in the process they gave us wonderfully exuberant films.

Thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team at Criterion. Thanks as well to Jared Case of George Eastman House for information about their print of Never Weaken.

Lloyd’s autobiography, An American Comedy, was timed to the 1928 release of Speedy, and it’s full of detail about gag structure and the production of his films. At one point he transfers our old friend, the distinction between suspense and surprise, to comedy. The book includes Frances Marion’s memorable line, “Harold, you’ve got to lose your pants.” Coauthored by Wesley Stout, An American Comedy was reprinted in a sturdy Dover edition with a 1966 interview and a cliché-challenging introduction by Richard Griffith.

Lloyd has been lucky in his admirers. Richard Schickel’s Harold Lloyd: The Shape of Laughter (New York Graphic Society, 1974) yields a finely sustained appreciation of his art. Adam Reilly’s Harold Lloyd: The King of Daredevil Comedy (Collier, 1977) is a vast compendium of biography, plot synopses, and visual documentation. Tom Dardis’s Harold Lloyd: The Man on the Clock (Viking, 1973) is a careful biography that situates Lloyd’s career in the development of the film industry. Donald W. McCaffrey offers a comparative study of plot structure in Three Classic Silent Screen Comedies Starring Harold Lloyd (Associated University Presses, 1976).

Most comprehensive of all is the remarkable Harold Lloyd Encyclopedia (McFarland, 2004) by Annette d’Agostino Lloyd (no relation). All the films are synopsized with credits and items from trade papers. Her Harold Lloyd: Magic in a Pair of Horn-Rimmed Glasses (BearManor, 2009) is full of fan enthusiasm, shrewd observation, and information I couldn’t find elsewhere. (She even checked Lloyd’s FBI file.) My Welles quotation above comes from this book, p. 167, as does Harold’s explanation of starting the Boy in one-reelers (pp. 85-86). The indefatigable d’Agostino Lloyd earlier produced Harold Lloyd: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1994).

The Agee essay is of course “Comedy’s Greatest Era” from 1949. My quotations come from James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland, vol. 5 in The Works of James Agee (University of Tennessee Press, 2017), p. 883. My Chaplin quote comes from Dardis’s biography, page 112. The quotation from Nicholas Kazan is in Jurgen Wolff and Kerry Cox, Top Secrets: Screenwriting (Lone Eagle, 1993), 134. Lloyd’s movie-measuring scheme is explained in P. A. Thomajin, “The Lafograf,” American Cinematographer (April 1928), 36-38, as applied to The Kid Brother, online here. The graph for Speedy is reproduced in Reilly’s Harold Lloyd, pp. 106-107.

A very pretty collection of early Lloyds is on Vimeo from Random Media. The standard DVD assemblage of features and shorts is the multiple-disc Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection. Several of these films are streaming on the Criterion Channel. Unfortunately, the version of Never Weaken (1921) available in these collections is a 1925 re-edit of the original three-reeler. The full version survives, however, and is available, in a so-so video, here. Criterion also offers an excellent Blu-ray disc of Speedy (1928), with solid extras, including an essay by Phillip Lopate and a visual essay on the film’s New York locations by Bruce Goldstein.

I analyze Ozu’s strong debt to Lloyd in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, pp. 152-159.

For the trivia fanatics: I think Harold’s manuscript in Girl Shy is mocking a sensational movie of a few years before, Men Who Have Made Love to Me. This film, written by Mary MacLane, an early feminist and scandal-rouser, was based on her memoirs. The movie is laid out in six parts, each devoted to the seduction method employed by one of her suitors. The film is lost, but it seems likely to have been the target of ridicule in the Lloyd picture.

Girl Shy (1924).

Posted in Criterion Channel, Directors: Lloyd, Harold, Film genres, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Silent film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel open printable version

| Comments Off on The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel

Sunday | December 10, 2017

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

Seeing Hong Sangsoo’s The Day a Pig Fell in the Well at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Festival didn’t convince me that he was a major talent. That happened two years later, when I saw The Power of Kangwon Province at the same event, and again at Cinédécouvertes in Brussels. At Hong Kong, and again at Brussels, I saw The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2001). In those days, Hong made a movie every year or two, like your ordinary director.

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007). I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

My apologies for playing an egocentric cinephile game. Boasting aside, though, I want to express genuine satisfaction at Hong’s sustained creativity. He has become prolific but not stale; every film offers the viewer and the filmmaker himself fresh challenges. What attracts me is his simplicity of means and the way he devises narrative games that make satiric points (usually about male vanity) without seeming mannered or precious.

He has gotten ever-greater recognition, as evidenced by the current Film Comment cover story, Dan Sullivan’s perceptive appreciation of his three (!) 2017 releases. Even more startling is a real high-culture breakthrough. In its print editions over the years, The New York Review of Books has resolutely ignored Kiarostami, Kitano, Wong Kar-wai, and Hou Hsiao-hsien, to pick some exceptional directors who hit their strides in the 1990s. But the 7 December NYRB boasts Phillip Lopate’s wide-ranging essay introducing Hong to its readership.

So he’s one of those overnight successes who took twenty years. Moreover, it’s gratifying to see that recently this body of work has had some influence, most apparent for me in the work of Lee Kwangkuk. Today I want to offer some notes on an intriguing, quietly ambitious filmmaker working in the shadow of Hong.

Two shorts

Hard to Say.

Lee learned on the job, assisting on Hong’s Tale of Cinema (2005), Woman on the Beach (2006), Like You Know It All (2009), and Hahaha (2010). His films have the crystalline cinematography and color design of Hong’s, and he has learned how to make movies that consist largely of two-person dialogues, shot in long, poised takes punctuated at just the right moment by a close-up. He has cast several actors who have appeared in his mentor’s films.

As with Hong, Lee’s characters tend to be artists: filmmakers in Romance Joe (2011), actors in A Matter of Interpretation (2014), and novelists in A Tiger in Winter (2017). They have romantic liaisons, but they also spend inordinate stretches of time wandering streets, hanging out, and drinking immense amounts of soju. And like Hong, Lee has experimented with storytelling formats.

Most obviously, there are embedded stories. Early and late Hong explored a modular narrative, broken into two or three blocks, with story lines splitting or converging. At first blush, Lee developed this in a more traditional direction, inserting stories within stories, Russian-doll fashion. His two favored forms of this are the flashback and the dream.

We get both in the short Hard to Say (2012). In a playground, a young woman declares her love for a young man, who puts her off, suggesting he’s been attracted to another woman, a guitarist. “You can imagine all you want,” he says, but he’s not going to be her boyfriend.

Saddened, the woman finds a guitar abandoned in the woods, and starts to listen to it. Cut to the boy, who’s now searching for the singer who played a song he loves. (Are we in a flashback?) He finds the young woman of the first scene, but as a different character, a poised and meditative guitarist. She tells him, via a flashback, how her father forbade her to learn the guitar, so she learned to play it in her imagination, in shadow strums and plucks.

When she finally got an instrument, she found she could play it perfectly. After her tale ends, she asks him to hug her.

Abruptly we’re back on the playground, where the original young woman is waking up from sleep. Now the boy is interested in her and offers to walk her home. The guitarist’s claim for the power of imagination is vindicated.

The fact that we’re not sure where the girl’s dream begins is conventional, but also characteristic of the way that Lee frays the boundaries of his embedded stories. And the fact that the boy has fallen in love with the girl while in her dream shows the porousness of the subjective stretch that’s embedded. Hard to Say provides a miniature example of how Lee’s characteristic plot structure prompts us to see stories within stories, and then refuses to keep them sealed tight. Early in a film, we might be led to expect a solidly implanted flashback, but soon the whole frame is revealed as less objective than we might think.

The transforming power of the imagination is given a more somber treatment in another short, Soju and Ice Cream (2016). A young woman fruitlessly selling insurance policies meets an old woman who asks her to fetch some ice cream in exchange for a basket of soju bottles. In one bottle our heroine finds a slip of paper, a sort of reformation vow written by the woman: “Do not give up. Make a plan. Stop drinking. Keep smiling.” Suddenly, in what appears to be a flashback, we’re watching the old woman write the note, in an apartment tagged with Post-its. She gets a phone call from her landlord evicting her.

The old woman casually blows into a bottle she’s just drained and, as if by magic, the girl hears and feels the breath.

Now able to listen to the old lady’s phone call, she discovers that the woman’s daughter treats her as harshly as she has treated her own mother.

The girl bursts in on the old woman–in the past? in her mind?–and pours her resentment of her mother into a criticism of the old lady for taking loved ones for granted.

Back at the ice-cream stall, she snaps out of her reverie to discover that the bottles are gone and the old woman is long dead. This touch of the fantastic has given her the chance to empathize with her mother and, in a long coda, to implore her sister to heal the family wounds. Here imagination yields not wish fulfillment, as in Hard to Say, but the recovery of duty and devotion.

Dream on

A Matter of Interpretation.

A Matter of Interpretation tackles dream narratives on a bigger scale. Yeon-shin, an actress, stalks out of a brutally awful avant-garde play because, among other problems, there is no audience. As she wanders the city, she recalls breaking up with her boyfriend a year or so ago. Now, on another bench, Yeon-shin meets a detective who claims to be able to interpret dreams. So she tells her dream of attempting suicide in a car halted in a field of goldenrod.

But a thumping from the trunk interrupts her, and she finds a man tied and gagged there. He’s the detective who had asked her about the very dream he’s now in. In a flashback he explains he found himself in the car, contemplating suicide, before she arrived.

We’re left with a dream that contains a flashback, as in Hard to Say. But it’s not a veridical one, since the man finds the pill bottle empty and Yeon-shin finds it full. So it’s a dream within a dream? Moreover, her dream features a character whom the dreamer did not know…until she recounted the dream. We’re entitled to take what we see as a version of what Yeon-shin told the detective, I suppose, with him plugged into the role that some faceless man played in the original dream. Or maybe she’s just fibbing. Or maybe what we’re seeing is a free elaboration of the situation, a startling variant without any source in her mind. The uncertainty, of course, is the point.

In any case, the detective interprets Yeon-shin’s dream as being about her dumping her ex, with the recurring car symbolizing her career failure. And now he explains his skill as a dream interpreter through a flashback to his caring for his ill sister, and her recounting a dream about a customer.

As the film goes on, we get to meet Yeon-shin’s boyfriend, Woo-yeon, through a string of flashbacks framed by her telling. Later in the day, he winds up on the bench with the detective, who probes one of his dreams–in which, again, the car and the detective appear.

Back in reality, in a string of precise repetitions, Woo-yeon follows Yeon-shin’s wanderings through the streets. And that night, exhausted and depressed, she has another dream that brings Woo-yeon back into her life.

Like Hard to Say, A Matter of Interpretation offers some legible time shifts–conventional framing situations for flashbacks–in order to give the imaginary scenes escape hatches, as the detective slips into the dreams recounted by the lovers. By the end, we’ve been prepared for their paths to cross, not least because Yeon-shin’s final dream presents a reconciliation she seems to yearn for.

Telling it backwards and sideways

There aren’t any dreams per se in Romance Joe, but it’s no less committed to the zigzag contours of the imagination. The plot presents several different time schemes (although some may be fictitious), and they don’t stay neatly separate. Again, there’s a benevolent contamination of one zone by another.

A young filmmaker has disappeared. His parents come to his friend Dam Seo to investigate.

Again, what seems to be a tidy flashback shows Dam meeting with the son, who rants that he’s run out of stories.

In a standard film, we’d return to Dam Seo and the parents for more discussion. Instead we’re now in a village, where a third filmmaker, director Lee, is dumped by his producer and ordered to conjure up a story pronto. Lounging in the hotel, Lee is brought coffee by a waitress who admires one of his films, A Good Guy, for its “critical approach to narrative.” Pleased, Lee asks her to stay the night, and she agrees, for money. He reminds him, she says, of another director who visited the town, the man she calls Romance Joe.

Joe, it turns out, is the missing, unnamed director the parents are worried about; but it’s not at all clear that Dam Seo is narrating this encounter of Lee and Rei-ji. How could he know about them? His flashback simply bleeds into a new set of scenes with these other characters.

Rei-ji tells of Joe’s coming to town, and in flashback we see him wandering the streets, then checking into a hotel and trying to write. Despondent, he starts to slash his wrist. That scene is interrupted by a flashback to Joe as a teenager finding a young woman, Cho-hee, with slashed wrists in a forest. He takes her to the hospital. At this point, the flashback-within-a-flashback ends. Rei-ji, delivering coffee, finds the bleeding Joe and hurries away.

Here, about thirty minutes in, we finally return to the initial situation of Dam Seo talking to the parents about their missing son. The father is dismissive: “All these kids today wasting their lives on film.” But the mother is sympathetic to Dam Seo and asks about his work. He says he’s working on a story, and he tries it out on them. This launches what can only be called a hypothetical sequence, about a boy visiting a town in search of his missing mother. But soon enough the boy encounters Rei-ji, the coffee-girl/hooker.

And the boy’s tale frays further when it’s interrupted by a scene of Cho-hee in the forest, starting to slash her wrists and then being discovered by the teenage Joe. There’s crosstalk among what ought to be distinct realms–Dam Seo’s script versus Cho-hee’s reality, one speaker’s story versus another’s.