Saturday | July 8, 2023

Wreck-It Ralph (2012).

Kristin here:

Way back in 2006, I posted a long piece on the increasing prominence of animated features being released each year. This was in the infancy of the blog, and the entry shows it–few photos, inserted as thumbnails. We only gradually worked up to our format of posting plenty of illustrations. By contrast this current contribution offers plenty of visual pleasure.

Basically I argued three points. First, that by their nature animated films would tend to be among the highest-quality films in any given year, despite their relatively small number in those days.

My argument laid out some reasons for this high quality. First, the fact that animated films were perforce thoroughly planned in pre-production, meaning that every detail was carefully considered. This means that relatively few inadequate scenes are reworked in production. Live-action films these days tend to be heavily dependent on shooting lots of coverage and making many decisions in the editing stage. Not true of animated films. Similarly, the soundtrack is recorded in advance and the images animated to sync with it. Hence the sound is meticulously planned. The voice actors record their voices and leave, usually not hanging around to try and change their scenes during shooting or fluffing lines and thus requiring multiple retakes of scenes.

My second point addressed the opinion, widely circulating in the trade press, that the spread of animation, and particularly digital animation, was a mistake. I quoted a recent Screen International article: “Much has been made this year of the seeming over-saturation of studios’ computer-generated titles, with critics and analysts pointing to growing movie-goer apathy.” I pointed out that such a claim didn’t fit the facts: “As a proportion among the total number of films made, CGI’s box-office successes seem fairly high compared to live-action films.”

My third point was that American distributors did not know how to market films from abroad, so that Ghibli and Aardman titles did not get nearly the audiences they deserved. Since then the distributor GKIDS has shown that it’s possible, at least for a relatively small company, successfully to release such films. They currently offer films with eleven best-animated feature Oscar nominations (with one win, Spirited Away), having gained distribution rights to Ghibli films, previously controlled by Disney.

Since I wrote that entry, the number of animated films, mostly digital, released yearly has sharply increased. And the disproportionate number of those animated films that appear among the top hits of the year continues to demonstrate that people are not apathetic. The spread of streaming services, combined with the decline of theatrical attendance during the pandemic, make it difficult to judge the success of films. Going back to 2019, where it’s a bit easier to judge, the top ten films included two animated successes, Toy Story 4 and Frozen II. An additional two were in the top twenty, How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World and The Secret Life of Pets 2. Animated films did not make up 20% of all films released, but that’s the portion of the top twenty they occupied.

I followed up that entry with one that found additional evidence that animated features were doing well, including the fact that Ice Age: The Meltdown was, though not the top box-office film of 2006, the most profitable film of that year.

So many developments have occurred in the world of feature animation since that first post that I decided to write an update.

The neighborhood is getting crowded

To some extent today’s update was inspired by a recent online post concerning new competition for Disney, which had absorbed Pixar and easily led the box-office race for years, with Dreamworks a second-run. Current developments led Alexandra Canal to point out some interesting figures. In 2022, Disney’s box-office total was $1.93 billion in ticket sales, for 26% of market share. Universal, number two, generated $1.64 million, for 22%, and Sony’s box-office coming in at a mere $834.8 million, or 11%. But things are changing. Other studios’ investments in building animation wings have started to challenge Disney’s dominance of the market for these films.

So far in 2023, as of July 1, Universal has The Super Mario Bros. (released April 5) at number one on the top-grossing list and over $1.3 billion worldwide. Sony has Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (June 2) at number four and approaching $620 million worldwide. By contrast, Disney has had two flops in recent memory: Lightyear (which I found mildly entertaining but not what I expect from Pixar) under-performed last summer, and Disney’s own Strange World (November 23) ended up with less than $74 million. Disney’s film in the top ten is the live-action version of The Little Mermaid (May 26), at number five with just over half a billion.

It will probably take several years for the long-term effects of streaming and the theatrical distribution recovery (if any) will have on Disney’s dominance. Still, it seems that the other Hollywood studios’ move toward creating their own animated departments is succeeding to some extent. The trend toward a greater variety of animated films may last.

Best Animated Feature or Best Picture? Which will win?

For this entry I have picked a rather arbitrary method of comparing quality animated films with quality live-action ones. I’m going to look at the Best Animated Films Oscar winners and nominees in comparison to the Best Picture ones.

Every now and then someone points out that such excellent animated films are now being turned out regularly that it would be logical to nominate the best of them for Oscars in the Best Picture category. There has never been a rule against such a crossover. So far it has only happened three times: Beauty and the Beast (1991, before the Best Animated Feature category existed), Up (2009), and Toy Story 3 (2010). None won, though they did take home Oscars in their own race. Other categories are technically open to animated films. Seven have been nominated for best screenplay, all Pixar films, with none winning.

A somewhat comparable situation has happened in the Foreign Language category. We tend to forget, but ten foreign-language films have been nominated for Best Picture: Grand Illusion (1938), Z (1969), The Emigrants (1972), Cries and Whispers (1973), Il Postino (1975), Life Is Beautiful (1998), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Babel and Letters from Iwo Jima (both 2006), Amour (2012), Roma (2018), Parasite (2019), Minari (2020), Drive My Car (2021), and All Quiet on the Western Front (2022). Oddly enough (maybe there was some change of rules), starting in 1998 with Life Is Beautiful, six of these also got nominated for Best Foreign Language film: Life Is Beautiful, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Amour, Roma, Parasite, Drive My Car, and All Quiet on the Western Front. All of them won in the Foreign-Language category, but only one, Parasite, won Best Picture as well. Presumably if a film was good enough to be nominated for best picture, it certainly would be good enough to win the Foreign-Language Oscar.

The same was true for animated films. Up and Toy Story 3 were nominated in both categories and won just the animation awards. (The animated feature award was started in 2002 for films released in 2001, so Beauty and the Beast could not do the same.)

Now we turn to another way of looking at the Best Picture and Best Animated Feature categories. If one is on Facebook, as I am, or, presumably, other social-media sites, as I am not, in many years one reads many vociferous complaints about the quality of the Best Picture winners. Since online people love lists, there are plenty of people weighing in on the ten worst films to have won that prize. These ten are usually fairly recent, since these online commentators usually don’t watch older films. Occasionally someone mentions Cavalcade (1933), but those are the real cinephiles.

I’m going to compare the Best Picture and Animated Feature nominees and winners, starting in 2002, when the latter category originated (for films released the previous year). The questions are, are some of the animated nominees and/or winners better than the live-action films that won Best Picture in the same year, and if so, how often does this happen? This is not, of course, to say that the Oscars are a true reflection of the cream of the crop, especially in the live-action Best Picture category. The best animated films (at least, English-language) tend to rise to the surface in terms of nominations because there simply are so few of them in comparison.

Logically, having chosen the Oscars as a means of comparison, I should compare all the excellent nominated animated films with all the excellent nominated live-action films. After all, the film or films deserving to win seldom do so. Maybe some of them are better than the animation winner. I’m not going to include all the nominees, because first, it would make this entry more lengthy and convoluted than it already is. Second, I haven’t seen all the nominees in either category, though I have seen a higher portion of the animated ones. Still, I shall mention in parentheses live-action titles that in my opinion were more deserving of the Best Picture Oscar than the actual winner.

I have seen all the animated winners and all of the live-action ones apart from Crash. Thanks to the reviewers and friends who warned me off the latter. (To be honest, I turned Chicago off about twenty minutes in.)

The Face-off

So let’s go year by year and see how the Best Picture fares against the Best Animated Feature–or in some cases multiple nominees in that category.

Going by release years rather than the years when the awards were given, we start with 2001. A Beautiful Mind was the winner. I’ve actually seen it on a list of worst-ever Best Pictures, but I think it’s a fairly good film. Shrek, the animated champ that year, was much admired, but I was disappointed by it. Monsters, Inc., however, was up against Shrek, and in my opinion deserved to win. It’s arguably better than A Beautiful Mind.

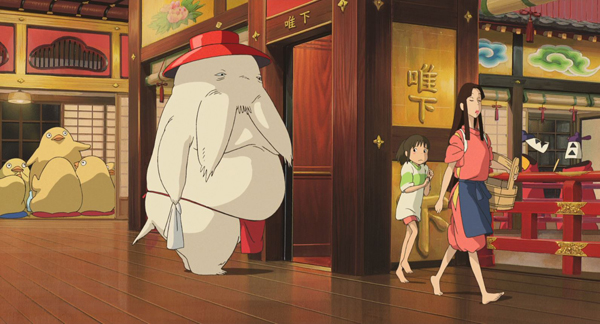

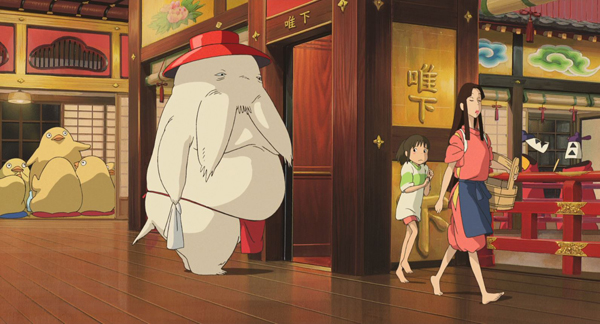

There’s no contest for 2002. Even today, awarding a foreign-language film the best-animated prize is nearly impossible–or indeed, a non-Hollywood one. (Non-American winners come from the UK and Australia.) To be sure, many Academy voters probably saw the dubbed version of Spirited Away. Nevertheless, the obvious sheer brilliance of Miyazaki’s film (above) won the day. Indeed, with Godard gone, Miyazaki may be our greatest living filmmaker–though no one can see enough films from around the world to make such a judgment.

2002 was the first year in which there were enough eligible animated features that five rather than three films were nominated, something that wouldn’t happen again until 2009. Nevertheless, the animated competition was pretty lackluster: Ice Age, Lilo and Stitch, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, and Treasure Planet. Spirited Away, arguably one of the greatest films of our current century, is miles beyond Chicago. If there is any evidence that the animated films can top the live-action ones, this year provided it.

Unlike our Supreme Court and other federal judges, I shall recuse myself from judging the 2003 contest. Having written a book on the subject of The Lord of the Rings film franchise and having had extraordinarily generous cooperation from the filmmakers, I can’t really be objective. Quite possibly Finding Nemo is better than The Return of the King,

2004 saw a return to only three animated features–a situation that would last until 2007. Three nominations were enough, however, since The Incredibles was up against Crash, a film high on many lists of the worst-ever winners. I doubt many would dispute my claim that The Incredibles won this face-off by a mile. (Again, I haven’t seen Crash or some of the other nominees, but I very much suspect that Spielberg’s Munich should have won.)

I am less confident in calling the 2005 winner. Million Dollar Baby is a decent film, though I wish Eastwood had not injected the heavy-handed point that Maggie wins Frankie’s heart because she’s a substitute for the daughter who has willfully disappeared from his life. Frankie losing his prejudice against training women boxers would be more powerful if it was simply based on her skill and determination. Still, I hesitate to say that the animation winner, Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (above), is better. (One of the English-language imports that have won.) I am a huge Aardman fan, but Wallace and Gromit work better in the shorts (especially the sublime The Wrong Trousers). Of the other two nominees in the category, Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride isn’t a contender, but one could make a case for Howl’s Moving Castle (Miyazaki again) as the film of the year.

Scorsese’s The Departed is a more complicated case in the 2006 face-off. Those of us who know the Hong Kong film it’s based on, Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Internal Affairs (2002), know how very much Scorsese used from the original. Plus who can forgive that final shot? Being a George Miller fan, I was quite disappointed by Happy Feet (the second English-language import to win). Rather bland, I thought, and certainly no Babe: Pig in the City (1998). I think Cars should have won best animated feature, and it outdoes The Departed as well. For some reason a lot of people don’t like Cars all that much compared to other Pixar films, which I don’t understand. Certainly Cars 2 is awful and Cars 3 pleasant enough. But the original is terrific.

The 2007 contest must be a draw. It’s hard to choose between the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men and Rataouille, the animated winner. (If Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood has won best picture, I would give it the edge over the Pixar film. It’s another of the great films of the current century.)

It’s safer to say that in 2008 WALL-E tops Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan’s Slumdog Millionaire. The first half hour of WALL-E, set on Earth, is perhaps the best thing Pixar has done. It falls apart a bit once the hero and Eve get onto the giant spaceship to which humanity has fled once the Earth became uninhabitable. It turns into a prolonged chase that isn’t nearly as interesting as the incredibly clever exploration of the detritus of civilization that WALL-E diligently searches through in that first half-hour. Still, for that half-hour, I give it the edge against Slumdog Millionaire.

In 2009, there were for the second time five animated nominees. The category would return to three in 2010, but thereafter there have always been five. Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker was probably one of the stronger films to win best picture in the period I’m covering. Still, can it really be said to be better than both Pixar’s Up (the winner) and Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox? And possibly Coraline or The Secret of Kells, Laika’s and Cartoon Saloon’s first entries into the fray respectively. (One benefit of writing this entry is that I watched for the first time all three of Tomm Moore’s lovely nominated Irish films, including The Song of the Sea and Wolfwalkers.)

My case is pretty strong in 2010. With only three nominees, the animated winner, Toy Story 3, easily tops Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech. (We should remember we’re in the period when Harvey Weinstein was bludgeoning his company’s films into the winner’s circle.) Some would say How to Train Your Dragon would as well. (Among the live-action nominees, I would vote for Inglourious Basterds, but it would be a miracle if the Academy members chose such a film.)

With 2011 we reach another case where the best-picture winner is widely decried as among the worst to pick up the trophy: Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist. The line-up of animated entries was pretty weak apart from Rango, directed by, of all people, Gore Verbinski. This brilliant outlier within the animation industry (produced by Nickelodeon), is a sort of cross between Chinatown and Once upon a Time in the West. That’s Rango with the villainous-tortoise mayor, above; the latter is a combination of Noah Cross in Chinatown and Mr. Choo-choo in Once upon a Time in the West.

Rango seems to have largely slipped from people’s memories, perhaps partly because it’s not a Disney or Pixar film that you buy on disc for your kids and have around forever. I don’t know what kids would make of Rango, but it’s definitely more aimed at adults. And hilariously imaginative.

2012 was a banner year for great animated films. The Oscar winner, Pixar’s Brave, was the first of six films in a row from Pixar and Disney, both at that point under the leadership of John Lasseter. I don’t find Brave among the best of these, but it’s OK and it no doubt benefited from all the fuss about it having Pixar’s first female protagonist. For me, there were no fewer than three wonderful nominees that were better: Laika’s Paranorman, Aardman’s The Pirates!: In an Adventure with Scientists! (the British title, changed to the much more boring The Pirates! Band of Misfits for North American release), and Disney’s Wreck-it Ralph. All three offer a flood of clever jokes and original concepts that could only be understood by adults. In Wreck-It-Ralph there’s the AA-style meeting of video-game villains that Ralph attends (top). Or in The Pirates!, the Pirate of the Year awards ceremony that puts the rival contestants in split-screen à la the Oscars show (second from top).

Any of them beats the “best picture,” Ben Affleck’s Argo. Remember that? (I haven’t seen all its live-action rivals, but Lincoln and Amour would have been creditable winners.)

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave fully deserved to win Best Picture. There’s certainly nothing to rival it in the somewhat set of nominations in the animation category. I did not find the winner, Disney’s Frozen, particularly interesting. It seems to be geared to appeal to small children. Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises was the only plausible nominee to go up against Sir Steve’s film, but I’m not going to make that argument. (It’s a real pity that Gravity was in the competition this year, since it truly is a great film and also deserved to win.)

Moving on to 2014, the live-action winner was Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Innocence). The list of animated nominees was not as strong as some years, but I think Birdman is overrated, and Disney’s Big Hero 6 tops it. (I’ve only seen some of the live-action nominees, but The Grand Budapest Hotel and some of the others were pretty strong contenders.)

In 2015 the winners in the two categories were Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight and Pixar’s Inside Out. I don’t really have a preference. (Here’s another case, similar to Inglourious Basterds, of a marvelous but violent, over-the-top masterpiece deserved Best Picture: Mad Max: Fury Road. It pretty much swept the technical awards to end up with six, but Spotlight won only two–picture and screenplay. Go figure.)

I remember watching Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight in a theater in 2016. I sat there thinking that this film was made by a talented young man who someday might win an Oscar. To me, his The Underground Railroad was a more impressive achievement and deserved a slew of Emmys. Three excellent animated films were nominated in 2016: Disney’s Zootopia, Laika’s Kubo and the Two Strings (bottom), and Disney’s Moana. I was convinced that Kubo would finally win Laika it’s first, well-deserved Oscar. Zootopia won over what I think is a slightly better film, Moana, but one can’t really complain in this case. (My preferences for Best Picture would have been Arrival and La La Land.)

The situation was reversed in 2017. Much though I like many of Guillermo del Tor’s films, I’d have to give Pixar’s Coco the edge over The Shape of Water (talk about a Mexican stand-off!). (The true masterpieces among the nominees that year were Nolan’s Dunkirk and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. At least, as so many of my friends have said, Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri didn’t win.)

Now we come to the notorious year of 2018, when Peter Farrelly’s (!) Green Book won best picture against competition that included Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman and Curaón’s Roma. This incomprehensible choice throws an even greater light on the high quality of the animated race that year. Three masterpieces were among the five nominees: Sony’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, which won, Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs (above), and Disney’s Ralph Breaks the Internet. Any one of these rolls right over Green Book. Incredibles 2 is pretty good as well. I enoyed the fifth nominee, Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai, but it hadn’t a chance against these three.

2019 is easy. Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite beats everything, even Pixar’s Toy Story 4. Probably a lot of people agreed with my assessment that the franchise was showing a bit of wear and tear, though not nearly as much as last year’s Lightyear. (Again, it’s a pity that two other masterpieces nominated that year couldn’t also win: Little Women and Once upon a Time in Hollywood.)

For 2020, when theater-going was difficult if not impossible, studios delayed many films or sent them straight to streaming. The result was a somewhat uninspired lineup of animated nominees. Soul almost inevitably won. I must admit that I preferred Pixar’s films as they were until recently–adventures of various sorts, whether involving actual superheroes, groups of toys, or an old man flying his house to South America to learn how to be sociable again. These had psychological depth, but they didn’t make it explicit by making emotions into characters or sending them to heaven. So Nomadland comes out ahead this time. (I would have preferred two other nominees, The Father or The Trial of the Chicago 7.)

In 2021 I found Sian Heder’s Coda as heartwarming as anyone, but Oscars are purportedly for picking great films that we assume till be watched in the future as classics. Not that they get it right very often, but, well, Oscar-bait ain’t what it used to be. The Danish animated documentary Flee leaves us with a tear in the eye as well, but the Academy stuck to its long habit of rewarding Pixar and/or Disney films and made Encanto its top animated film. This film had many good moments, but it annoyed me every time it got into a lively scene. Suddenly the characters (and virtual camera) started zipping about through the settings. Those settings were gorgeous, but we didn’t get a chance to look at them. Just compare it with Moana, which also had scenery worth lingering over while still managing to drip with exuberance. (For the live-action champ, I would have gone for Nightmare Alley, The Power of the Dog, or West Side Story. It was a pretty good year.)

There was, however, one animated feature nominated that year: the unmissable The Mitchells vs. the Machines–though many may have missed it when during the pandemic it skipped theatrical and went straight to Netflix. It was produced by Phil Lord and Chris Miller, who also did Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse for Sony Pictures Animation, and although a very different film, it has all the energy, imagination, and craziness of that film. It also plays out the potentially apocalyptic rebellion against humans by AI and the robots run by it. The premise is that an angry computing system being replaced by a new generation sends robots to put all humans in plastic cubes and fire them into space–including its own inventor. The dysfunctional Mitchells are humanity’s only hope. The funniest and most telling scene is when they stop at a mall and all the products in the stores, which have chips installed holding a kill order to destroy the family, start attacking them. This culminates in a bunch of Furbies going after them, led by the world’s largest Furby (above).

What happened in the 2022 category is sort of like what happened in 2002, when Spirited Away won. An outlier from outside the traditional Hollywood studio structure (Netflix) was nominated among a somewhat weak group of animated films and won the day. I settled down to watch the broadcast of the ceremony wondering if Academy members would recognize what a remarkable film Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio is and not just reflexively vote for the Pixar film. That was Turning Red, which got a lot of attention for daring to show a teenager hitting puberty and experiencing her first period. I didn’t think it was a very good film and confirmed my sense that Pixar has declined in recent years. It’s probably better than The Good Dinosaur and now Lightyear, which is not saying much. (Carolyn Giardina’s recent “Elemental Steps into the Ring in Major Box Office Test for Pixar,” astutely sums up reasons for the aesthetic decline of Pixar–and, one might add Disney Animation.)

I know a lot of people for some reason are enthralled by Everything, Everywhere, All at Once, which won the 2022 Best Picture. I found it mildly entertaining but at least it gave Michelle Yeoh a career win for Best Actress. Pinocchio is miles beyond it. (Everything won against a slew of superior films. In alphabetical order: The Banshees of Inisherin, The Fabelsmans, Tár, and Women Talking.)

Totting up the live-action vs. animation winners in this face-off, we find one recusal, one draw, five decisions in favor of the live-action winners and fourteen for the animated winner or one or more of the animated nominees. As I mentioned at the start, the figures would be quite different if I had compared all the Oscar-worthy animation awards with all the Oscar-worthy Best Picture nominees. Still, in general this comparison may suggest that animated films are unfairly treated as one of the minor categories that people don’t pay much attention to.

I’m not suggesting that the Academy change their categories or rules. There’s probably no way to boost the prestige of the Animated Feature nominees.

The point here has simply been to add some evidence to my claim that a higher percentage of animated films tend to be excellent in a way that compares favorably with the live-action films nominated in the more prestigious category. Despite this, animated films are simply not taken seriously by most people, inclined cinephiles. They are still viewed as children’s fare, despite the successful appeal to adults built into many of the titles I’ve singled out here. They are also mostly comic to some extent and often involve fantasy, while Oscar bait leans toward drama and, with rare exceptions, away from fantasy/science fiction.

The conclusion is that if you think, for whatever reason, that live-action Oscar winners and films in general have declined in the past few decades, check out some ‘toons.

Kubo and the Two Strings (2016).

Posted in Film comments |  open printable version

| Comments Off on “Best Picture” ≠ “Live Action” open printable version

| Comments Off on “Best Picture” ≠ “Live Action”

Sunday | June 25, 2023

Poker Face, Ep. 10 (“The Hook”).

DB here:

Charlie Cale, an easygoing but tough young woman from New Jersey, has a unique gift. She can detect when someone is lying. She has exploited this in a career as an itinerant poker player, but after the word gets out about her ability, she winds up working as a waitress in a Las Vegas casino. A free spirit, she enjoys living from paycheck to paycheck, sharing beers and smokes with other staff. But the casino boss Stirling Ford Sr. learns of her gift and recruits her for a scheme targeting a rich patron.

That scheme collapses, and Charlie winds up having to flee across the United States. Driving the backroads, trying to stay off the grid, she keeps running into crimes in a wide range of settings. She stops at a Nevada Subway shop, a Texas barbecue joint, a stock-car race, a dinner theatre, a special-effects movie company, the venues of a touring heavy-metal band, a care facility for the elderly, and a remote mountain motel. We come to know each of these with remarkable specificity, noting details like lottery tickets and music amplifiers and Steenbeck flatbeds.

Charlie has the common touch. When she spots a lie, she’s likely to blurt out, “Bullshit!” She can freely talk and eat with working stiffs and is naturally suspicious of the plutocrats she keeps running into. She’s ready to deploy her ability to expose the less wealthy who want to exploit others. Eventually we come to learn that her sympathy for virtuous innocents may be compensation for her frosty relations with her family.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo. Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

Apart from enjoying Poker Face on its own terms, I’ve admired its efforts to innovate. In my book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder I argue that we have three useful tools for understanding plots. We can ask about the sequence of events in time; the way point of view structures our access to those events; and the way the events are broken into distinct parts. Noting how the plot handles time, viewpoint, and segmentation can help us grasp the ways Johnson has revivified the classic mystery–in ways that shape our experience.

I’ve had to indulge in spoilers, but I decided to confine those wholly to the first episode. Later episodes would justify a similar depth of analysis. And even in the first episode, I’ve tried to conceal major plot points when I could. In any event, I hope that people who haven’t yet seen the show (streaming on Peacock) might be intrigued enough to try it. It’s free although interrupted by commercials, but in a nifty use of segmentation Johnson manages to turn their timing to his advantage.

The inverted plot

Columbo, Ep. 1 (“Murder by the Book,” 1971).

The typical investigation plot begins with the crime already committed. The detective proceeds to unearth earlier events that led up to it. The alternative is, unreasonably, called the “inverted” plot. Here we witness the crime committed and perhaps are shown the motives involved. Then the detective arrives on the scene and we watch the investigator try to discover what we already know. We watch for slip-ups in what initially seems a foolproof scheme.

The inverted schema was developed most vividly in the Golden Age by F. Austin Freeman in a series of short stories. His sleuth, Dr. Thorndyke, arrives on the scene only after we have watched the culprit do the deed. The puzzle comes in trying to grasp how Thorndyke, using reasoning and scientific analysis, solves the mystery. In the process, he sometimes calls our attention to betraying details that we didn’t notice on the first pass.

This pattern of action comes off well in the short-story format, but it can be difficult to sustain in a longer tale. So the author may have the culprit resort to trying to impede or confuse the ongoing investigation, or to committing other crimes that need solution as well. These techniques come into play in Freeman’s novel Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight, which devolves into a battle of wits between Thorndyke and Pottermack.

A similar sort of stretching was common in Columbo, whose reliance on inverted plots inspired Johnson for Poker Face. The first episode broadcast, “Murder by the Book” (directed by Steven Spielberg), starts with disgruntled author Ken Franklin shooting his collaborator. Columbo, in his rumpled raincoat, doesn’t show up for the first eighteen minutes, and even after that he’s offstage during Franklin’s further schemings. These include creating a false trail for the crime and killing a witness who threatens him with blackmail.

We get some access to Columbo’s investigation behind the scenes, but the high points are his visits to Franklin. We enjoy the clash of slob versus snob when this obtuse flatfoot peppers the wealthy author with maddening questions–and always seems to accept a lie in reply. Eventually, when Franklin is trapped, Columbo reveals that he suspected him from the start; he just needed more evidence.

Despite its name, the inverted plot is usually linear. It traces events chronologically from crime to punishment, though flashbacks may provide chunks of backstory. This is where Johnson saw an opportunity to try something new. Assuming that viewers are familiar with the inverted plot schema, he juggles the sequence of events in unusual ways–exploring a different time layout in each episode.

A matter of timing

Poker Face, Ep. 1 (“Dead Man’s Hand,” 2023).

Except for the final installment, Poker Face follows the inverted schema: crime first, then investigation. But after we see the crime committed, the episode’s narration typically skips back and even “sideways” to show us circumstances leading up to the deed. Eventually the crime will be take its place in the chronological sequence–perhaps through a brief replay, or at least by reference in dialogue. Put another way, the crime segment is a kind of flashforward.

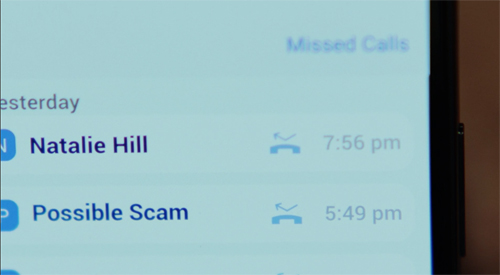

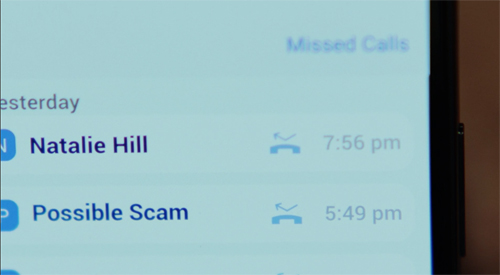

The first episode, “Dead Man’s Hand,” provides a tutorial in method. In a Las Vegas casino, the housekeeper Natalie finds horrific pornography on the open laptop of Kasimir Caine, a millionaire guest. She reports it to the boss, Sterling Frost Junior, and his fixer Cliff. They send her home. Cliff follows and shoots Natalie in her living room. He’s already shot her husband Jerry and he arranges the scene to look like a murder-suicide.

This block of brief scenes is followed by a linear story starting a few days earlier. Charlie works at the casino as a waitress, and she offers Natalie a place to stay after her drunken husband Jerry has raised a ruckus in the gaming room. In the meantime, Frost Jr. has learned of Charlie’s lie-detection talent and recruited her to watch Caine’s clandestine poker game by remote transmission. Frost will use her information about who’s bluffing in order to fleece Caine, while proving to his father that he’s a good manager.

Frost’s scheming with Charlie is interrupted by Natalie’s visit to report Caine’s pornography, so now the lead-in sequence falls into place. While Charlie is briefed further by Frost, Cliff is offstage killing Natalie and Jerry. The pivot is signaled by repeated dialogue: Cliff phones Frost (“It’s done”) and Frost resumes his explanation (“Where were we?”). The sequence of events is firmed up the next morning, when Charlie sees an online report of Natalie’s death.

The rest follows chronologically. Charlie feels guilty for not returning Natalie’s call, made shortly before her death.

Her phone record leads her to notice disparities in the timeline and investigate, while she and Frost Jr. are preparing for the Caine scam. A slip of the tongue allows her to spot Frost’s lie about Cliff’s call, and he realizes she’s on to him. The result is Frost’s death and his father’s demand that Cliff capture Charlie. She flees and begins her backroads odyssey across America.

Later Poker Face episodes elaborate this template. Sometimes the crime is embedded in a large block of consecutive scenes, with all the backstory shown (ep. 2, “The Night Shift”). After that we skip back to still earlier events centering on Charlie’s travels leading up to the night of the murder, which takes place while she is next door in a tavern. That’s why I said that some of the scenes move sideways, showing incidents near her. This “proximity principle” is pushed further in ep. 3, “The Stall,” when Charlie is hovering just offscreen in the opening scene, as the murder conditions are laid out; the replay will reveal that.

Another variant: The leadup to the crime is extended for much longer than in the earlier episodes, with the murder coming a third of the way through the show’s running time (ep. 4, “Rest in Metal”) and the replay witnessed by Charlie over halfway through. Later episodes adopt mixed strategies. They still start with the crime, or at least the planning, and skip back in time, but they seed the later blocks with ellipses, brief flashbacks, and replays. It’s as if the series were teaching us week by week to accept an increasing flexibility in moving forward and backward and sideways, while still adhering to the basic convention of the inverted plot. We’re also helped, of course, by dialogue and intertitles telling us where we are in the timeline.

The exception to these pyrotechnics is the last episode, “The Hook.” It’s stubbornly linear in tracing Cliff’s pursuit of Charlie. It starts ab initio, with Frost Sr. ordering him to find her, and following that with scenes from earlier episodes in which Cliff misses her. In a way, this entire prologue is a kind of flashback that ends with him seizing her as she leaves a Colorado hospital. The final episode is the most conventionally readable because it isn’t an inverted plot. The crime is missing from the opening but is saved, as is common, for a climactic revelation.

What makes all this variation possible is a coordination of segmentation, viewpoint, and causal-chronological order. The blocks of time are dictated by attachment to the killer (s) or to Charlie. Typically the lead-up to the crime keeps us with the culprits. The flashbacks following the first statement of the crime are motivated because they’re attached to Charlie, who is just getting involved with the situation. The later segments are either purely tied to her, or (as in the Columbo episode) devoted to the culprit’s efforts to thwart her inquiry. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” for instance, scenes of her investigation are garnished with moments in which Frost Jr. and Cliff plan ways to circumvent her. In all, these maneuvers create pretty clever plots, their segments accented by the way that the end of a block tends to initiate a commercial break . . . just as in old network TV.

Charlie’s little gray cells

Poker Face, Ep. 8 (“The Orpheus Syndrome, 2022).

How good a detective is Charlie? Given her gift, shouldn’t sleuthing be utterly easy? Johnson has engineered his series to give her several handicaps that require her to sweat as much as any hardboiled dick.

For one thing, as a working-class woman of fairly slight stature, she starts by facing a bias in favor of the bulky, wealthy men (mostly) whom she challenges. In addition, after the first episode, she’s on the run and has to be discreet. Going to the police about anything would inevitably reveal her whereabouts to Frost Sr. Moreover, during her flight she’s deprived of what helped her crack the first case: her cellphone access to the internet. After Frost Sr. threatens that he will find her, she destroys her phone so she can’t be tracked. But now she’s got to rely on other sources of information.

Even her gift proves problematic. Unless a suspect explicitly denies committing the crim, her bullshit detector can’t know the person is guilty. Not incidentally, this condition puts a fruitful constraint on the screenwriters. They have to make sure the culprit’s dialogue circumvents the sort of declaration that Charlie would see through.

Confronted by all these obstacles, Charlie is obliged to act like a classic detective. Let’s count the ways.

For all the pledges to strict reasoning, the traditional sleuth is often triggered by intuition, the sense that something is just not right here. (The prototype is Chesterton’s Father Brown, but even logicians like Ellery Queen and Hercule Poirot are sensitive to “atmosphere.”) Charlie’s gift is an extravagant form of intuition, since it’s both illogical and impossible to explain scientifically, so even when it doesn’t expose the killer it can set off a minor alarm. In the season’s first episode, her suspicion is aroused when Frost Jr. lies about his phone conversation with Cliff.

The classic detective spots or unearths clues, traces of the criminal’s action and pointers to identity. Charlie’s case against Frost Jr. and Cliff in “Dead Man’s Hand” is built out of such traditional clues as a problematic timetable, uncharacteristic behavior (Natalie didn’t sign out when she left work), and hand dominance (would a leftie wield a pistol with his right?). Later episodes of Poker Face are packed with physical clues, from wood splinters to discarded candy wrappers. As Jacques Barzun puts it, in the classic detective story “bits of matter matter.”

Charlie is especially good at spotting the absent clue, the dog that didn’t bark in the night-time. In the first episode, she notices that video footage of Jerry hustled out of the casino shows him passing through Security unscathed.

But if he had his pistol with him, that would have been detected–which implies that Cliff kept it. Yet Golden Age conventions demand fair play: we must have access to all the clues the detective has. In his films Johnson has adhered to this, and he has in Poker Face. So we are shown the Security station in the casino twice earlier. Early on, Cliff breezes through, counting on the staff’s recognizing him and letting him pass.

Later, Charlie is stopped because her phone sets off the scanner.

Consequently, when Jerry doesn’t set off the alarm as Charlie had, he can’t be packing the gun.

Reasoning puts the clues together, but sheer reasoning isn’t enough to justify arresting somebody. There must be evidence. Charlie often finds herself convinced of the killer’s guilt but lacking something that would stand up in court. And without a cellphone she can’t resort to tricking the killer into confessing on a hot mic. Yet some solid evidence is needed to clinch the case. The screenwriters have been ingenious in finding other damning records. Episodes recruit heart-monitor charts, 16mm film, CCTV footage, and digital audio and video captured by Charlie’s helpers or the culprits themselves.

In a classic whodunit, as we approach the climax, the detective is often blessed with a stroke of good luck that advances the solution of the puzzle. It’s often something apparently trivial–an overheard conversation or a slip of the tongue, or an irrelevant detail that inspires the detective to reinterpret a clue. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” Charlie spots the TV report of Jerry passing through Security not by diligent research but by sheer accident. She’s just dropped by the bar when the broadcast appears.

One more convention, one that the series adopts gradually: an alliance between detective and law enforcement. The classic detective cooperates to some extent with the police, either wholeheartedly (Queen, Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey) or grudgingly (Nero Wolfe). Even tough guys like Sam Spade, Nick Charles, and Philip Marlowe may exchange information with their friends on the force. At the start of Poker Face Charlie is a loner, but as the series proceeds, she gain an ally in the FBI, and because she helps him crack cases he comes to her aid on occasion. “At this rate, if I stick with you I’ll be head of the Bureau in a year.”

In all, Poker Face has engagingly modernized the inverted plot schema while benefiting from classic principles. Those permit the detective to show off powerful intuition, systematic reasoning, and Machiavellian cleverness in trapping the prey. In addition, the series has added to the gallery of admirable sleuths a hard-boiled but compassionate wise-guy woman. And it’s done with a strong dose of social criticism. This have-not from Jersey wreaks vengeance on those who victimize innocents.

Poker Face is scheduled for a second season, with Charlie once more on the run across America. We may expect that it will continue to show how ingenious play with time, viewpoint, and segmentation can revivify conventions of the whodunit. Keen fans learned to ask not only How will Charlie discover the crime we’ve seen committed? but also ask, with a teasing meta-curiosity: What ellipses and time jumps and hidden clues will we get this episode? Johnson seems unlikely to give up the game any time soon.

In Deadline, Antonia Blyth provides a very informative interview with Rian Johnson and Natasha Lyonne about Poker Face.

Martin Edwards discusses the inverted plot schema as part of a broader trend toward empirical, scientific investigation techniques in The Life of Crime (2022), Chapter 10. For a thorough survey of Freeman’s work, see Mike Grost’s discussion. Jacques Barzun emphasizes the role of physical clues in his superb essay, “Detection and Literature,” The Energies of Art: Studies of Authors Classic and Modern (1956), 313.

I discuss the inverted plot in more detail in Chapter 5 of Perplexing Plots, considering it as a hybrid of the pure investigation plot and the psychological thriller.

Poker Face, Ep. 3 (“The Stall,” 2023).

Posted in Directors: Johnson, Rian, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book), Television |  open printable version

| Comments Off on POKER FACE: Detective off the grid open printable version

| Comments Off on POKER FACE: Detective off the grid

Saturday | May 27, 2023

Asteroid City (2023).

DB here:

Asteroid City tells two stories. One ends more or less happily, the other more or less sadly.

The first one takes place in roadside America, 1955. In a minuscule town made famous by an asteroid crater, five finalists for Junior Stargazer awards assemble with parents and siblings for the ceremony. They mingle with the locals, the scientists at the observatory, a batch of primary-school kids, a military unit, and an itinerant cowpoke band. The big day is interrupted by the arrival of an alien bent on retrieving the asteroid. This exceptionally polite invasion spurs all of the visitors to reconsider their life options. After a second visit from the alien, the travelers leave. Enlightened? A little bit.

This story is shot in anamorphic widescreen and color as glowing as Kodachrome. The second story, interwoven with the first one, is presented in 4:3 black and white. It presents episodes from a television program purporting to document the production of a typical American play. But the host, a generic, all-knowing announcer, tells us that the play “Asteroid City” does not exist, was never performed and has only an “apocryphal” existence, whatever that means.

But instead of the usual behind-the-scenes chronicle of putting on a show, we get only glimpses of preparation and performance, arranged out of chronological order. We hear alternative speeches and learn of scenes that will eventually be cut. The last stretch of the second story is a morose reflection on what the play might mean, with the director’s response to that question a simple: “Just keep telling the story.” As if in reply, the epilogue of the visitors’ Asteroid City adventure is the (rousing) conclusion of the whole movie we’re watching.

Like Marianne Moore’s “imaginary gardens with real toads in them,” Asteroid City (the town) is a fantasy world, but it’s not free of danger. There’s death. Atomic tests are conducted next door.

Within this carpentered world, all right-angled motel cottages and perpendicular lanes and train tracks, two forces are at work. There is Science, embodied in the astronomical research of Professor Hickenlooper and her fanciful accounts of cosmic activity. The Junior Stargazers have all come up with wild breakthroughs–a tethered jet pack, a way of projecting pictures on the moon–that prove that these teenagers are both brilliant and eccentric. From one angle the film, like Rushmore and The Life Aquatic, is a defense of visionary nerds.

Counterposed to Science is, not to put a fine point on it, Christianity. The kids brought to the ceremony by June recite prayers on command. Faith enters more poignantly with the Steenbeck family, headed by the photojournalist Augie. His wife has died, but not until they stop in Asteroid City does he break the news to his son Woodrow and three little daughters. It impels the girls to bury her cremated remains in a Tupperware bowl as they try out proper reverence. Is she in Heaven? Augie doesn’t believe in it, and Woodrow is uncertain, but it’s real for the girls, Augie says, because they’re Episcopalian.

Neither Science nor Christianity can account for the alien, or the strange indicia it has inscribed on the asteroid. The creature’s arrival comes at almost exactly the film’s midpoint, and thereafter hazy outlines of happy endings emerge. No spoilers, but here’s a hint: Love is involved.

All of which makes the film sound terribly abstract. It’s not. The clumsy online parodies of Anderson’s style make us forget how crisply economical it is. Forget movies padded out with cars pulling up or pulling away, close-ups of coffee being made, characters hunched over cellphones and workstations, roundy-roundy camera movements, and drone shots floating over a metropolis. Every shot here carries its fair weight.

Anderson’s geometric framing and staging demand a stream of small details. Moment by moment we have to take in gorgeous Populuxe furnishings, rapid dialogue, enigmatic signage, non sequiturs, abbreviated gestures and glances, and flickers of facial expression. For a few seconds a cigarette lighter is casually refilled with a squirt of gasoline (a good example of Brecht’s gestus, the piece of performance that crystallizes a social attitude: we’ll have oil forever). Soon enough a gizmo pulled from Augie’s decrepit engine thrashes on its own: Is this the alien? Just the range of cultural references dazzles. Anderson’s love of theatre emerges in recollections of plays from The Petrified Forest to Bus Stop, by way of Wilder and Williams. And are all the variants on a nonexistent play text his contribution to multiverse storytelling?

The embedded film has opened with a roaring freight train to a male voice singing “Last Train to San Fernando,” a song that celebrates a desperate chance for love. The whole film ends with a version of “Freight Train, Go So Fast” about a man being hanged, yet it’s sung by a mourning woman with sheer exhilaration. Asteroid City (the film) is poised between love and death, in the process celebrating the muted joy and welcome eccentricity of everyday life.

Not to mention hot dogs, chili, and strawberry milk.

Asteroid City has attracted many favorable Cannes reviews, but I’ve been disappointed in the dismissive comments offered by reviewers I respect. Many have taken the obvious line of objection (trademark whimsy, too many stars, too much artifice) without coming to grips with the distinctive qualities of the film. (But Bilge Eberi , Manohla Dargis, Richard Brody, and Glenn Kenny get it.) This seems to me one of Anderson’s very best works. It has a richness that my sketch here can’t capture, and I hope to write more about it later.

For more blog entries on Anderson’s films, go here.

PS 11 July: The streaming version of Asteroid City just released on Amazon Prime is of very poor photographic quality: low contrast and desaturated color. A version more faithful to the film is available on Apple +. I haven’t checked other sources.

Asteroid City (2023).

Posted in Directors: Anderson, Wes, Readers' Favorite Entries |  open printable version

| Comments Off on ASTEROID CITY adrift in the cosmos open printable version

| Comments Off on ASTEROID CITY adrift in the cosmos

Sunday | May 21, 2023

Babylon (2023).

DB here:

The circus parade has just passed, and behind it comes a little man mopping up all the droppings left by the lions, tigers, camels, and elephants. Somebody calls out, “Why don’t you quit that lousy job?”

The little man answers: “Are you kidding? And leave show business?”

From one angle, the joke anticipates the dramatic arc of Babylon. Damien Chazelle’s film traces how five characters seeking a future in the movies immerse themselves in a debauched culture, all for the sake of the dream machine.

For trumpeter Sidney Palmer and singer/actor Fay Zhu, the movie moguls’ bacchanals pay the bills and allow networking. Jack Conrad, a major star, loves being a drunken libertine but expresses contempt for the films he makes, movies that are only “pieces of shit” rather than innovative high art. Manuel Torres becomes an all-purpose gofer on set and eventually a studio executive, trying to work within the system. Nellie LaRoy is attracted to the movie world as much for the whirl of drink, drugs, dance, gambling, and fornication as for the glamor drenching the screen. Finding her film persona as the Wild Child, she can act by acting out.

These characters, all from working class origins, are brought together at a moment of technological upheaval: the period 1926-1934, with the establishment of talking pictures. This would seem to threaten moviemaking, not to mention the high life offscreen. Other pressures include the stock market collapse and the resulting depression, along with the establishment of a stricter standard of what could be depicted onscreen, the famous Hays Code. (The Code isn’t mentioned directly in Babylon, but it’s suggested as part of a broader concern with morality in the film colony.)

By the time sound has fully arrived, all of Babylon‘s primary characters, voluntarily or not, are no longer working in the Hollywood industry. Fay Zhu leaves for European production. Sidney, whose band is ideal for sound cinema, quits in disgust after he’s forced to darken his skin further. When the press and the public turn against Jack, he commits suicide. Nellie dances off into darkness and a lonely death. Manny, vainly in love with Nellie, can’t halt her self-destruction and has to flee town to avoid reprisals from the mob. From this angle, a confluence of debauchery and technology has wrecked whatever spark of life the system had.

The bleak satire that is Babylon poses a host of questions. Why, for instance, are there apparently deliberate anachronisms? The backdrop sets for the Vitoscope’s outdoor filming would be unlikely for 1926. Jack misquotes Gone with the Wind a decade before the book was published. The vast opening orgy seems more typical of Von Stroheim’s films than any actual Hollywood party on record. And given Vitoscope’s marginal status, how does the studio head afford such a mansion?

But I’m interested today in the ways the characters seek fame. I think their situations are a development of qualities we’ve seen in other Chazelle show-biz films. One way or another, nearly all those characters have sought to find a creative impulse that can make the compromise with a corrupt system yield some artistic rewards. The pressures and temptations of Babylon are extreme versions of factors we’ve seen at work in Whiplash and La La Land, but the characters react rather differently.

The suicidal drive for perfection

Whiplash (2014).

I think about that day

I left him at a Greyhound station

West of Santa Fé

We were seventeen, but he was sweet and it was true

Still I did what I had to do

‘Cause I just knew. . . .

These are the first lines we hear at the start of La La Land. Sung by a young woman slipping out of her car, they foreshadow the film’s plot developments. Sebastian and Mia, the couple at the center, both put their careers ahead of their love for each other and separate at the end. Each seeks success–Mia in screen acting, Sebastian in starting a jazz club–and that drive blocks a compromise in which one or both might give up their dreams for the sake of staying together.

Chazelle’s first two show-biz films present artistic achievement as a solitary quest that demands you to surrender normal ties to others. His strivers are loners, unable to subordinate their “dreams” to the demands of mutual love. Sacrificing everything to their quest, they have the self-righteous egocentrism of Romantic poets.

Whiplash tells the story of Andrew Neiman, an aspiring jazz drummer in music school. Worshipping Buddy Rich, he wants to be “one of the greats” himself. He spends hours in grueling solitary practice, and he has no friends. He is distant from his family, except for his father, with whom he goes to movies as if he were still a kid. He gives up a beginning romance with a young woman because, he tells her, he needs the time to practice.

The film introduces Andrew alone, bent over the drum kit, a distant figure in a corridor. In what follows, Chazelle isolates him, not through overwrought long shots showing him as remote from other students, but en passant, by medium shots that let us glimpse them in normal hallway conversation behind him.

Apart from competing with his peers, Andrew runs into Terence Fletcher, the fearsome leader of the school’s top jazz ensemble. Fletcher finds him practicing, invites him to try out for the band, and proceeds to run him through a program of brutal aggression, laced with just enough encouragement to keep Andrew on the hook. Good father/ bad father: the dynamic seems primal, but it’s an unequal struggle. Fletcher, always clad in satanic hipster black, knows how to dangle the prospect of success in front of Andrew’s bleary eyes.

That success comes in some degree, but haltingly. Andrew rises in the ranks, but through a series of unlucky mishaps, he humiliates himself in a major competition and assaults Fletcher onstage. He’s kicked out of school, but he’s also pressed to testify about his teacher’s abuse. It remains for Fletcher to entice Andrew one more time, tricking him into another public fiasco. Yet Andrew turns it into a sort of triumph.

Fletcher bullies Andrew into saying, “I’m here for a reason.” That reason, to put it in highfalutin terms, is the prospect of excellence within a worthy artistic tradition. To become as good as Buddy Rich is a wonderful prospect. But that’s a rosy picture. Breaking with Nicole, Andrew displays some of Fletcher’s cold-bloodedness, leading her to ask in her parting line, “What the fuck’s wrong with you?” She’s referring to his chopping off human ties, but she might as well be stressing Whiplash‘s suggestion that with that purity comes an eager masochism that is heightened by the master’s sadism. To be an artist is to sacrifice normal human ties but also to submit to a punishing game of power.

That game is played out in the career of Andrew’s idol. Buddy Rich, a technical virtuoso, had a combative view of musicianship. He conducted celebrated duels with other drummers and was said to have believed that for him, the drum was the solo instrument and the orchestra merely a batch of accompanists. As a bandleader, he was famous for vituperative attacks on his players. At once an obsessive like Andrew and a tyrant like Fletcher, he personifies the performer as a solitary seeker after inhuman perfection.

In what appears to be a burst of sincerity, Fletcher tells Andrew that the abuse he inflicts is solely to push the player to go beyond what’s expected. Only that will create the next Charlie Parker. Learning of the suicide of a student he tormented, he seems genuinely shaken–although he lies to his players by saying the boy died in a traffic accident. The sheer aggression that darkens his quest for quality is revealed when he deliberately sabotages his ensemble’s performance to make Andrew flub the piece.

At this point, though, Andrew catches some of Fletcher’s fury by launching into a maniacal solo. In its frenzied drive, it seems as if it could go on forever. By sheer force he wrests control of the orchestra from Fletcher, who seems with a smile to recognize what has happened and eventually plays along. He guides Andrew in a Rich-like descent into slower, then faster tempo. Reconciled with the strict father and the whiplashes he’s received, Andrew has demonstrated his heedless devotion to an exceptionally severe jazz tradition.

Music and machine

La La Land (2016).

Before it enacts the lovers’ separation foreshadowed in the opening song, La La Land gives us two protagonists aspiring to show-business success. Mia runs around town auditioning for TV shows, while Sebastian nurtures the dream of opening a jazz club. Like Andrew in Whiplash, Mia’s a loner with no deep relation with her peers. Sebastian, also a loner, harbors a conception of jazz playing that’s as combative as Buddy Rich’s. He explains a performance not as a communal exchange but as rivalry.

Look at the sax player right now. He just hijacked the song. He’s on his own trip. Every one of these guys is composing, they’re rearranging, they’re writing, and they’re playing the melody. And now the trumpet player, he’s got his own idea. And so it’s conflict and it’s compromise. . .

The game can get deadly. “Sidney Bechet shot somebody because they told him he played a wrong note.”

What drives the young and hopeful? The opening song suggests two impulses. First, there’s the fantasy realm of movies. “A Technicolor world made out of music and machine/ It called me to be on that screen/ And live inside each scene.” Second, there’s an urge to show the people back home that you’ve made it. “‘Cause maybe in that sleepy town/ He’ll sit one day, the lights are down/ He’ll see my face and think of how he/ used to know me.”

But neither purpose seems to be primary for Seb and Mia. True, Seb is a movie fan who quotes James Dean, but the couple aren’t apparently driven by fantasy. And although Mia comes from the sticks, she isn’t vindictive about it. Instead, they worry about succumbing to the mediocrity of the world they want to enter.

Jazz is dying, Sebastian laments. He plays at a piano bar and can’t introduce his own playlist. He picks up work as a keyboardist in an uninspiring but successful progressive-R&B ensemble. Mia auditions for clichéd roles and is facing a life as a barista.

The emptiness of their milieu is encapsulated in two party scenes. Unlike the infectious party in Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009), these are scenes of careerist networking. Parties, Mia’s roommates argue, are essential for advancement; the person you schmooze today could hire you tomorrow (“Someone in the Crowd”). At the first party, confronted by snobs, Mia flees to the bathroom to confront herself in a mirror: Who is she really going to be? When she comes out, the party has become a sterile erotic tableau.

The alternative to giving people what they want is giving them you. Because Sebastian has found something of himself in jazz, he urges Mia to express herself in a one-woman show. She has her own tradition–the Hollywood movies her aunt showed her, and which she mimicked in skits she mounted as a girl. The show earns her an audition, where she channels her own experience in a song monologue about her aunt’s Paris adventures (“The Fools Who Dream”). It’s something of a reply to her mirror scene at the party. She gets the part, a lead to be built around her as a character.

Her successs and Sebastian’s steady if uninspiring life on tour initiate their breakup. Neither will sacrifice a career for a life together. Jazz may be conflict and compromise, but the only compromise visible here comes in the alternative time-frame climax showing the couple sharing domestic happiness. Somehow Mia has found stardom, with Seb as supportive spouse. But that’s a hypothetical outcome. As in Whiplash, you can achieve excellence by commitment to a personal tradition, but at the cost of close ties to others.

Party like it’s 1926

In the show-biz musicals, Chazelle’s protagonists’ goals aren’t defined as specific achievements–not winning a drumming prize but somehow becoming a drumming great, not getting a part in a particular show but getting some part in any show. Accordingly, like many off-Hollywood efforts, the films have episodic plot structures. Scenes tend to be more or less self-contained, with few dangling causes to lead to the next. Deadlines are set within a series of end-stopped scenes, not for the film as a whole. The action may be driven by coincidence, accident, and happenstance.

The episodic quality is less evident in Whiplash, whose scenes are dictated by scheduled rehearsals, solitary practice, and concert dates. Even there a flat tire, followed by a car crash, adds to the dramatic tension, and coincidence reintroduces Andrew to Fletcher after both have left the school. La La Land gives us a cascade of meet-cutes before the couple finally goes on a date. After that, their career trajectories depend chiefly on fortunate job offers, but also on Seb’s failing to remember a photo shoot. At the climax, a coincidental moment of traffic gridlock brings her and her beefcake husband back to the club to encounter Sebastian and the prospect of the future that might have been.

Moving from one protagonist to two to several in Babylon, Chazelle’s episodic inclination poses new problems. The major characters aren’t intimately connected, as in many network narratives. Manny is in love with Nellie, but he rarely sees her, and then only by accident. All are linked by being in the Hollywood system, and for the most part Chazelle is obliged to rely on crosscutting to interweave their developing careers.

The technique synchronizes their trajectories. Nellie is hired as actor at the first party, while Manny becomes Jack’s aide by escorting him home. The next day, as Nellie finds surprise success in her role for Vitoscope, Manny saves MGM’s costume picture by fetching a camera in time for a magic-hour shot. (The roots of Hollywood: a last-minute rescue.) Nellie’s rise to second lead is paralleled to Jack’s success in Blood and Gold, while Manny becomes Jack’s trusted assistant, sent to New York to catch the premiere of The Jazz Singer.

As the industry tries to assimilate sound, Nellie struggles and MGM hires Manny to supervise its Spanish-language production and coordinate musical shorts with Sidney’s band. Jack’s films start to bomb, Nellie’s star image goes out of style, and Manny rejoins Kinoscope to rehabilitate her. She remains a wild child, however, and Jack starts to realize his career is ending.

The storylines come to bleak endings when Jack commits suicide and Nellie drags Manny into her downward spiral, making them targets of James McKay’s mob. Once separated, Nellie vanishes and Manny flees the business. Sidney returns to playing live jazz for Black audiences, and his solo accompanies a montage sequence launched by Jack’s funeral and including a news story about Nellie’s 1938 death, possibly of a drug overdose.

To bring these protagonists physically together, Babylon relies chiefly on parties–five, by my count. The first and most sumptuous is an orgy hosted by Kinoscope’s boss Don Wallach. It demonstrates the dissipation of Hollywood culture. How could the comparative purity of Andrew or Mia or Sebastian survive this plunge into the mire? If nothing convinces one of the need to stand apart from the Hollywood milieu, this explosion of decadence should do it. Manny is a fixer (the guy sweeping up after the parade). Jack samples the fruits–a drink here, a quick copulation there–but Nellie is utterly in her element. She becomes the life of the party. If hedonism is an index of stardom, she shows, as she says, she was a star the moment she walked in.

At the party, Nellie and Manny explain why they’re attracted to this milieu. Manny says he wants to be part of something bigger, and he loves movies because they let you live the characters’ lives. Nellie agrees. Later, after she’s hired, she’ll holler that this will show everybody who said she was a loser. The two rationales–immersive fantasy and surprising the folks back home–are the same ones given in the opening song of La La Land. They have nothing to do with artistry in a tradition.

Jack’s case is a little different. He defends film as a high art, claiming that it needs a shot of modernism akin to Bauhaus design or twelve-tone music. Yet he has so little respect for his art that he plays his roles in an alcoholic stupor and condemns most films as shit. And claiming that sound would be as revolutionary as perspective in painting seems sheer silliness, especially after his joyless role in a regimented rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain.” In his longest tirade, he drops back to a mass-popularity argument. He tells his current wife that his immigrant parents found meaning in the nickelodeon, and millions more people will see him than will visit an O’Neill play.

You can argue that, like Mia in La La Land, Nellie and Jack succeed through self-expression. Nellie can cry on command because she remembers home; Jack cuts a dashing figure by his very nature. But they don’t work at their craft, or discipline their self-expression. Offscreen Nellie is a wastrel and Jack is a drunken pseud, babbling Italian, playing opera records, and garbling highbrow debates about mass culture and high art. Natural vitality gives Nellie and Jack some currency in the turmoil of silent film, but the discipline of talkies renders them obsolete.

They’re bereft of a tradition, though Jack senses the need for one. By contrast, Sidney has not only the jazz tradition but also, surprisingly, Scriabin. (Though in the Fletcher vein he admires Scriabin’s mutilation of his hands to play virtuoso passages.) It’s Sidney who quits the business out of principle. Not incidentally, he and Lady Fay seem the only protagonists with a powerful talents.

The second party, also hosted by Wallach, is somewhat more sedate than the first, though Nellie can be glimpsed nuzzling a unicorn’s horn. This initiates a montage that culminates in Nellie ecstatically watching her screen performance with an audience, who assail her for autographs.

The third party announces “Hooray for Sound” and brings together the three major characters in a night of frenzied activity. It’s reminiscent of the opening bacchanal, but seems more desperate, driving Nellie to break more bounds by daring death from a rattlesnake. (Lady Fay is the only partygoer bold enough to rescue her.) When Jack sees the melée that results, an uncharacteristically sustained and sober close-up, scored to a doleful piano, suggests that he senses that his milieu is headed for self-destruction.

Next party, far more upscale: Nellie tries to display her rehabilitation at a luncheon at a millionaire’s mansion. But her clumsy efforts to be genteel are mocked and so she lets loose with obscenity, attacks on food, and aggressive vomiting. Jack, Manny, Sidney, and FeiZhu have assimilated, but Nellie reverts to being the raucous low-life from Jersey. It’s career suicide. In parallel sequences we see Sidney forced into blackface and Jack frozen out by MGM.

The fifth party is a nightmarish descent into purgatory. “LA’s last real party,” McKay says as he ushers Manny and his colleague into a labyrinth of degenerate spectacle. Echoes such as the song “Her Girl’s Pussy” reveal the initial orgy as naive devilry: here is real shock. It’s as if the denizens of Hollywood have had their nerves rubbed so raw that only the most sadistic and gruesome entertainment will satisfy. Has this party been going all these years?

Taken all in all, it seems to me that the party sequences make explicit what the La La Land parties only suggested: to succumb to this milieu is fatal. The solitary quest of these lost souls render them vulnerable to temptations that will ruin them. In the Biblical Babylon, by pursuing false gods, the feasters have been weighed in the balance and found wanting. This is the story of people who think the party life (on the set of off) can last forever.

Granted, unlike Mia and Sebastian, the protagonists of Babylon have no other paths to their art. In the studio system, old-timers have assured us, you had to socialize with the decision-makers if you were to have a career. There were no equivalents of niche music clubs or indie film producers. In an odd way, Babylon is a roundabout tribute to the fluid artworld of today.

But then there’s the much-discussed final sequence.

Movies are bigger than ever

It’s 1952. Manny and his wife and daughter are visiting Los Angeles from New York, where Manny has a radio repair shop. As his wife and daughter return to their hotel, Manny drifts from the still-existent Kinoscope studio to a theatre. He finds himself in an audience watching Singin’ in the Rain. He sits transfixed, but his viewing is interrupted by a montage sequence that is, to say the least, a challenge to us.

What if the montage weren’t there? We’d have a scene in which Manny watches the new MGM movie restage the problems of early sound he witnessed, the tyranny of the mike and camera booth. He weeps. But then comes Kelly’s “Singin’ in the Rain,” which revises the mechanical chorus of old. Manny smiles. In his lifetime, the naive clumsiness of sound has been transmuted into something smooth and beautiful.

No wonder at the very end Manny is transported. He has achieved his hope of becoming part of something big. He has contributed to perfecting that imaginary world onscreen. We’d have what William Dean Howells claimed was the story all Americans wanted, “a tragedy with a happy ending.”

Hollywood has long justified its existence by appeal to magic. Disney provides the Magic Kingdom, while Lucas labeled his high-tech wizardry Industrial Light and Magic. At intervals throughout Babylon, characters echo the cliché. Jack calls a movie set the most magical place on earth; after his career has plummeted, he recalls the silent era in the same terms. The gossip columnist Elinor St. John celebrates “the camera’s magic tricks” in filming a battle. Without the inserted montage, Babylon‘s finale would confirm this mysterious magic, the way junk (the movies we see being made) can somehow become something splendid.

But we have that montage. Although it harbors many implications, it has the effect of sabotaging an upbeat ending. After a few shots recalling earlier scenes in the film (ending with the cliché of the couple passionately kissing), there’s a fusillade of images. They are snipped from silent cinema, abstract films, animation, widescreen splendors, foreign-language films, avant-garde films, computer films, CGI images, and wholly digital creations. Significantly, there are no Hollywood films represented from the 1930-1938 years we see in the last stretch of Babylon. It’s as if the visual narration is reminding us that the “something bigger” is indeed bigger than anything Manny experienced.

From one angle, it’s also a chronicle of technological change, all the “revolutions” that would follow the coming of sound. But where’s the magic? The usual counter to the mystique of magic is to point out the hard work of filmmaking. What delights us, on that account, is proficiency in craft and ingenious mastery of a tradition.

Chazelle floats another possibility. Having presented the digital future, he gives us luxurious images of dyes being mixed in colorful arabesques. Black-and-white footage is plunged into the brew.

What emerges are tinted versions of paradigmatic shots of the film we’ve seen: Nellie dancing on the bar, Jack on the promontory above the battlefield. Among more shots of the dyes mingling we see Sidney and Fay Zhu, now also tinted. The scenes we’ve seen have become part of silent film.

Bursts of pure color, interrupted by glimpses of live-action, close the montage.

The image is dissolved back into its most basic ingredients. A movie that started with a spray of elephant shit ends with streaks of translucent liquid sinuously circling one another. Movie magic, it seems, is a kind of alchemy, a distillation of molecular mixing within the hardware of filming, processing, and projection.

It’s tempting to take Elinor’s bleak consolation of Jack as the movie’s point: Long after he’s gone, future audiences will see him as a friend, at once an angel and a ghost. Perhaps the medium redeems anything it touches, lifting Nellie’s antics and Jack’s swagger to a luminous life everlasting. But this prospect negates the artistic premises of the two earlier films. Without a guiding passion to succeed through achievement, and with only an ebullient personality (Nellie) and some masculine grace (Jack) and a dutiful resourcefulness (Manny), have-nots can succeed in show business. For a while. When the parade is over, what’s left are spectral traces of its passing.

I have to say that decadent frescos like Babylon aren’t usually to my taste. I don’t much care for La Dolce Vita, Satyricon, The Damned, and comparable spectacles of luscious degradation. They have a moralistic, not to say moralizing tenor. But, as I tried to show here, liking or disliking a movie on grounds of taste doesn’t make the film uninteresting. A film can gain interest in the light of questions we can ask about its form, style, and themes (including political ones). On these grounds, the films by Fellini and Visconti remain important parts of the history of film, regardless of whether I find them sensationalistic. Similarly, while Babylon isn’t my favorite Chazelle film, I can appreciate its virtuosity, as in the frenzied crosscutting of the two 1926 shoots. I can also find its thematic inversion of his earlier work worth thinking about.

I don’t know what Chazelle the person thinks about artistic ambition and self-sacrifice. I do think that he has found a narrative model of the process that allows him to ask questions about whether creation is private or communal, self-expression or commitment to a tradition, ascetic denial or plunge into sensory distraction and self-exploitation. Most films never raise such questions.

On Buddy Rich’s style and career, I learned a lot from Jonathan Godsall’s article “Whiplash, Buddy Rich, and Visual Virtuosity in Drumkit Performance,” Twentieth-Century Music 19, 2 (2022), 283-309. Godsall is also good on how Chazelle’s cutting enhances Andrew’s performance.

Marya E. Gates offers a wide-ranging account of Babylon‘s references to silent-era filmmakers in this piece in Indiewire.

A helpful summary of the image-capsule montage at the film’s end is offered by Anthony Olesziewicz in Collider. Initially the sequence might seem to be Manny’s flashback, but the opening glimpses of his life in LA are quickly followed by examples ranging across film history, including years since 1952, which suggest a narrational commentary, like a footnote.

There are entries on other Chazelle films on this blog: La La Land (here and here) and First Man (here).

Babylon (2023).

Posted in Directors: Chazelle, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Hollywood: The business |  open printable version

| Comments Off on BABYLON and the alchemy of fame open printable version