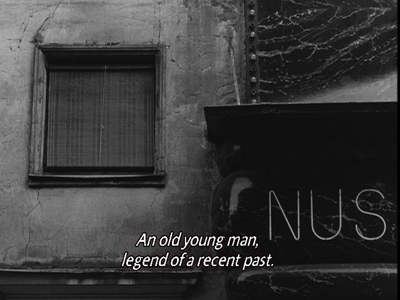

The Underneath (1995).

DB here:

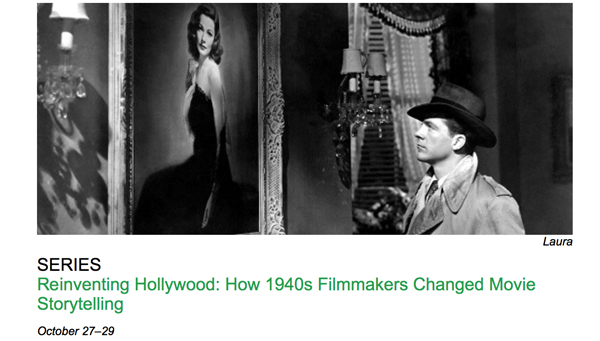

The announcement of Ocean’s Eight (premiering, when else?, on 8 June next year) reminded me of the staying power of the heist genre, also known as the big-caper film. I discuss it a bit in Reinventing Hollywood, my book on 1940s storytelling, but it developed and spread out most vigorously from the 1950s on.

In its origins it relies on masculine roles; if women are present they’re likely to be at best helpers, at worst traitors. The big job is likely to be endangered by a man telling his wife or mistress too much, and then the police or rival gangs may interfere. So the news that Ocean’s Eight will center on a female gang constitutes an intriguing wrinkle. (Will a boyfriend try to spoil the caper?) Warners’ ambitions for another trilogy seem evident: presumably the entry is Eight because Warners hopes for a Nine and a Ten. Commenters are already worried that a “feminized” version runs the risk of flopping the way Ghostbusters did last year, but I’m more hopeful. The reason is that clever storytelling is encouraged in this genre. There’s a chance that the film, produced though not directed by Steven Soderbergh, will show us that this old dog has new tricks.

Because I’m interested in the storytelling strategies of popular cinema, the heist film is a natural thing for me to consider. Refreshing the genre may involve not just adjusting the story world—giving men’s roles to women—but also considering ways of handling two other dimensions of narrative: plot structure and cinematic narration. I argue in Reinventing that Hollywood filmmaking uses a sort of variorum principle, a pressure to explore as many narrative devices as possible within the constraints of tradition. For this reason, the prospect of Ocean’s Eight prodded me to think about how convention and innovation work in the caper movie. It’s also a good excuse to go back and watch some skilful cinema.

From the fringes to the core

The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

It’s useful to think of a genre as a category having a core and a periphery. At the core are prime, “pure” instances: prototypes. Stretching out from it are less central, fuzzier cases. Prototypical musicals are Footlight Parade, Shall We Dance?, Meet Me in St. Louis, and My Fair Lady. Somewhat less central are concert films and musical biopics like Lady Sings the Blues and Coal Miner’s Daughter. At the periphery are movies with a single song or dance number. Of course the category changes across history; a critic in 1960 might have picked North by Northwest as a prototypical spy thriller, but ten years later a Bond film would have probably held that place.

The prototypical heist film, critics seem to agree, doesn’t just include a robbery. There are robberies in films about Robin Hood and gentleman thieves like Raffles and the Saint. The outlaw or bandit film like They Live by Night and Bonnie and Clyde contains a string of robberies, but they wouldn’t be at the center of the heist category.

Donald Westlake proposed a concise characterization: “We follow the crooks before, during, and after a crime, usually a robbery.” This indicates two things. First, the plot is structured around the big caper, though there might be lesser crimes enabling it, such as stealing weapons. Second, the viewpoint is organized around the criminals, not the detectives who might pursue them, as in a police procedural. By these criteria, High Sierra (1941), although allied to the bandit tradition, fits because most of the film concerns a single robbery, its preparations and aftermath.

Westlake shrewdly goes on to note that the interest of a heist plot inverts that of the traditional locked-room detective story. Instead of wondering how something difficult was done, we wonder how something difficult will be done. “The puzzle exists before the crime is committed.” To fill in the how, crooks with specific skills (safecracking, demolition, getaway driving, and so on) are recruited. Because the process matters so much, Westlake adds that heist plots focus on details of time and physical circumstance, and they draw attention to impediments such as “dogs, locks, alarms, watchmen, and complicated traps.” Most of these features are missing from High Sierra; we’re not encouraged to speculate how the job will be pulled, there’s little meticulous planning and no division of labor by expertise, and the only dog is friendly. So it’s unlikely to be a core instance of the genre as we now consider it.

Most critics consider The Asphalt Jungle (novel, 1949; film, 1950) a solid prototype. In fiction and film it’s not the very earliest instance, but it displays what we might call the “completed arc” of a heist plot. A gang of varying talents is assembled and funded to pull off a jewel robbery, which succeeds partly at first and eventually fails.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

Criss-Cross and The Asphalt Jungle show that we’re dealing with an exceptionally schematic plot pattern. For convenience we can distinguish five parts.

Circumstances lead one or more characters to decide to execute a heist (robbery, hijacking, kidnapping).

The initiators recruit participants.

As a group they are briefed and prepare their plan. They study their target, rehearse their scheme, or take steps to make it easier.

The heist itself begins and concludes.

The aftermath of the heist, failed or successful, shows the fates of the participants.

There are other conventions, nicely laid out by Stuart Kaminsky in 1974 and more recently by Daryl Lee. But I’ll just concentrate on this structure and how it governs narration, because these aspects show very clearly the constant dynamic of schema and revision in the filmmaking tradition.

Four capers, mostly unhappy

Criss Cross (1948).

Four films in the period covered in my book point toward the heist genre, though only one became a core instance. The presence of a “consolidating” film might be one way genres emerge.

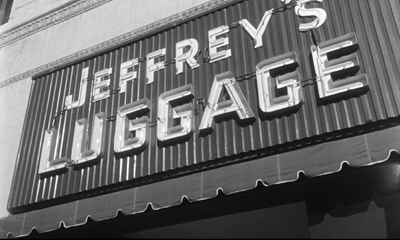

The earliest candidate is an unlikely one. In 1941 Laura and S. J. Perelman mounted a notably unsuccessful play called The Night Before Christmas, a farce in which crooks buy a luggage store in order to tunnel from its basement into the bank vault next door. Although Paramount was a backer of the stage show, Warners bought the rights and revamped it for Edward G. Robinson, who had had success in gangster comedies like A Slight Case of Murder (1938). The adaptation, Larceny, Inc. (1942) maintained the premise but revised the plot, multiplying the complications that face the leader Pressure and his two minions. The twist is that thanks to Pressure’s daughter, who’s unaware of the scheme, business starts booming and the crooks find themselves prosperous businessmen. Woody Allen swiped the premise for his Small-Time Crooks (2000).

Just as we don’t expect a comedy to be the initial entry in a genre mostly associated with drama, we might expect that the early entries in the genre would be the tidiest, with complex variations building on them. Actually, two precursors of The Asphalt Jungle display remarkable complexity.

The simpler one, Criss Cross (1948), starts late in the preparation phase: the night before the caper, when the gang is holding a party to distract a local cop who has his eye on them. We learn that Steve is working with Slim’s wife Anna to double-cross the gang. The next day, Steve is driving the armored car and recalling how he got into this situation. A flashback provides the circumstances for the robbery—Steve’s pursuit of Anna, her marrying Slim, and Steve’s impulsive proposal of a robbery to protect Anna from Slim’s punishment.

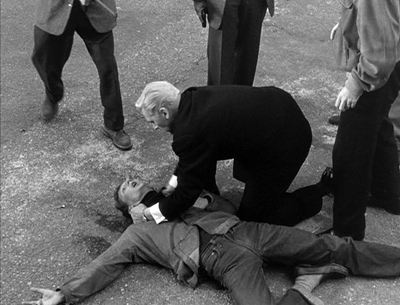

Next comes the planning phase. The robbers assemble and the task is reviewed by a mastermind they hire. This second flashback ends and, back in the present, we see the heist itself. The aftermath of the bloody robbery shows Steve in the hospital, honored by the community. A thug kidnaps him and takes him to Anna. Slim has survived the gun battle and finds the couple; he kills them before he is mowed down by the police.

Early as Criss Cross is in the history of the film genre, the plot components are already being scrambled. Thanks to 1940s Hollywood’s commitment to flashbacks and character subjectivity, the novel’s linear action gets fractured, compressed, and stretched. Moreover, in most films, the decision to pull the heist is made fairly early. Here and in the novel, circumstances slowly force Steve to rescue Anna from the man who mistreats her. The buildup to this decision consumes nearly fifty minutes of an 87-minute movie. Similarly, the aftermath of the heist is quite protracted, running about twenty minutes. And whereas other films (and novels) dwell on the recruitment of thieving talent, here this is elided. That’s because the other members of the gang are less significant than the central triangle of Steve, Anna, and Slim.

The Killers (1946) is even more complex because it clamps the block construction of Citizen Kane onto the heist schema. We start with one bit of the heist aftermath: the death of the gas-station attendant Ole. Like Kane, who also dies in his bed at the start of his film, Ole is the protagonist of the past-tense story. We next meet the protagonist of the present-time story, the insurance investigator Riordan, who functions like the reporter Thompson in Kane, and sometimes even gets the same silhouette treatment.

The rest of the film splits up the basic parts of the heist schema, rearranges their order, and presents them through a series of several flashback blocks, anchored in six characters’ testimony.

The heist itself is very brief, running only about two minutes, and the planning phase is only a little longer. As in Criss Cross, the leadup and the aftermath constitute the bulk of the film, but these phases are broken up into many bits, and these are often shuffled out of chronological order. We see Ole’s discovery by Big Jim years after the heist and then we see Ole, days after the heist, distressed that his lover Kitty has betrayed him. Similarly, a crucial event after the heist—Ole’s stealing the loot from the gang—precedes a scene before the heist in which he learns the gang is planning to double-cross him. We have to reconstruct the canonical sequence, from circumstance to aftermath, out of fragments revealed in testimony taken by Riordan.

Critics haven’t taken Criss Cross and The Killers as the first core instances of the heist film, perhaps because these movies complicate the classic plot template. In addition, they downplay the planning and execution phases. The heist scenes are relatively minor compared to the time devoted to other phases, particularly the circumstantial buildup. Moreover, the robber teams aren’t vividly characterized and don’t display a range of expertise. The emphasis falls on Steve and Ole, both played by Burt Lancaster, as the beautiful losers who become suckers for treacherous women and their brutal men.

By contrast, the linearity of The Asphalt Jungle throws the plot template into crisp relief. Both novel and film offer a full-blown enactment of central features picked out by Stuart Kaminsky. The gang, despite low social standing, has many skills. They’re held together by a leader who may also be a brainy planner. The robbers’ plan requires “skill, practice, training, and above all, perfect timing.” The gang’s resourcefulness is tested by accidents. The caper is partly successful but largely a failure, often through sexual weakness on the part of some players.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

The novel lays out the canonical action phases with surgical efficiency. But as in the films I’ve just mentioned, the planning and the heist itself take relatively little space. Given so many characters’ contribution to the action, their gradual convergence and their dispersed fates dominate the book. Over a hundred pages are devoted to setting up the circumstances and recruiting the gang. The aftermath, tracing the outcome for all involved, runs another 140 pages.

The film adaptation retains the novel’s scope, trimming only a couple of minor characters. It moves briskly among the ensemble, attaching us to several in turn, so we know more than any one character does. The narration creates parallels among the team members and their affiliates (such as four women of different classes, with varying commitments to their men).

The result is something of a network narrative, a cross-section of several people whose lives change because of the robbery. There’s no clear-cut protagonist like Steve in Criss Cross. Dr. Riedenschneider has the most screen time, but the film begins and ends with the hooligan Dix, and the fate of both men dominates the climax. I point out in Reinventing Hollywood that a multiple-protagonist film often gives extra weight to one or two characters.

50s and 60s stylings

Violent Saturday (1955).

With The Asphalt Jungle as a robust prototype, writers and filmmakers developed the heist plot throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Despite his clumsy style (”He nodded with his head”), Lionel White became known as “the king of the caper novel” for his tireless variants on robberies, hijackings, and kidnappings. The other major figure was the far superior Donald Westlake, who wrote brutal heist tales as “Richard Stark” and comic ones under his own name.

In the comic register, Westlake was beaten to the post by heist films from England. The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) showed a timid clerk engineering the theft of gold bullion, which he disguises as kitschy miniature Eiffel Towers. The Lady Killers (1955) centered on a gang fooling their landlady into thinking that their planning meetings are actually string-quartet sessions. In Italy, the classic Big Deal on Madonna Street (I soliti ignoti, 1958) showed five incompetents trying to break into a pawnshop safe.

Big Deal was considered a parody of a much more serious film, one that was by then a landmark: Rififi (Du rififi chez les hommes, 1955). It did a great deal to consolidate the genre in France, along with Touchez pas au grisbi (1954) and Bob le flambeur (1956). (Both The Killers and Criss Cross had been imported in the Forties.) In England, the heist drama was seen in The Good Die Young (1954), while in the US there were 5 Against the House (1955), Violent Saturday (1955), Plunder Road (1957), The Big Caper (1957, from a White novel), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). The year 1960 saw a remarkable number of releases, with The League of Gentlemen (U.K.), The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, Seven Thieves, and most famously Ocean’s 11 (all U.S.).

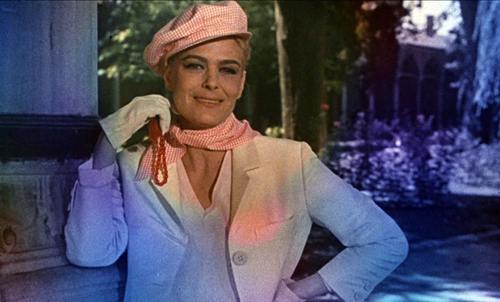

Through the 1960s the genre proliferated, including a remake of The Asphalt Jungle (Cairo, 1963), Jules Dassin’s near-self-parody of Rififi (Topkapi, 1964), and a string of heist films that mixed in romantic comedy (e.g., Gambit, 1966; How to Steal a Million, 1966). The Italian Job (1964) became a cult movie, with tourists visiting the sites of shooting in Turin. The genre has remained robust throughout world cinema ever since.

The very rigidity of its format and the constraints it lays down, have allowed for ingenious innovations. I’ll sample some of those from the genre’s first dozen or so years, concentrating on three areas: the differing emphasis given to the plot phases; variants of point-of-view; and manipulations of time.

Where’s the action?

Rififi (1955).

The Asphalt Jungle offers a fairly pure geometry: the heist, lasting about eleven minutes, ends just before the film’s midpoint. On the other side of that is another big scene: a gunfight initiated by Emmerich’s henchman Brannom when Dr. Riedenschneider and Dix bring in the loot. That confrontation takes another seven minutes, so the heist and its immediate wrapup sit at the center of the running time. What led up to the heist, the circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases, consume the first forty-five minutes of the film, and the aftermath of the heist, affecting the surviving characters, will take just about as long. This balanced geometry, putting the heist snugly at the center of the plot but devoting most time to showing many lives leading up to and away from the crime, suits the extensive characterization of all involved.

This is a neat structure, but not the only possibility. Any phase of the action can be given great weight. The first half hour of Bob le flambeur is an episodic introduction to Bob’s routines and associates. It’s the circumstantial phase—he’s running out of money—presented at low pressure, emphasizing instead the fascinating milieu Bob coolly drifts through. Only when Roger points out a croupier at the Nantes casino does Bob formulate “the job of a lifetime.” Then crew assembly and planning can begin. As the plot develops, characters and relationships presented casually in the exposition become crucial to the heist and its unraveling.

Other phases can be stretched out. Ocean’s 11 dwells on the phase of gathering the talent. Before the start, Danny Ocean has already conceived the heist, but we aren’t told the plan. Instead we watch his team members converge on Las Vegas. Not until the film’s midpoint, at 53:00, is the plan revealed in a briefing. The dawdling exposition suits a film about cool guys hanging out.

The formation of the crew is exceptionally protracted in Odds Against Tomorrow, because here two members hesitate about participating. The racist Earl Slater, wracked by the shame of not providing for his wife, finally gets her to agree to let him join. Not until twenty-three minutes from the end does the African-American musician Johnny Ingram finally accept a role in the heist, which immediately becomes the film’s climax.

The source for Odds Against Tomorrow (one of the better heist novels) handles the basic pattern very differently, putting the heist just before the midpoint and devoting the second half of the book to the increasingly hopeless getaway, where the interracial tensions play out at length.

The planning phase sometimes includes a rehearsal for the heist, and that may require a subsidiary crime, such as stealing keys or a vehicle. The League of Gentlemen has an unusually long planning phase, in which the gang masquerades as soldiers in order to seize weapons from a military post. This robbery, running nearly twenty minutes, takes longer than the film’s main heist but serves to demonstrate the team’s resourcefulness and esprit de corps. The men’s precision and resourcefulness (based on their wartime experience) lead us to expect a successful main event.

Kaminsky suggests that the big-caper genre resembles the soldiers-on-a-mission movie, which centers on the details of a process executed by skillful specialists. That display of process comes to the fore in The Asphalt Jungle’s central robbery, which initiated the convention of detailing the mechanics of the heist. Other films expanded the heist sequence to larger proportions than was evident in The Killers or Criss Cross. Rififi became the model; its heist runs twenty-five minutes without any words being spoken. (That sequence is part of an even longer wordless stretch that runs over thirty minutes.) Dassin’s film meticulously breaks down the steps of a complicated robbery, allowing us to appreciate the men’s clever planning while, as usual, ratcheting up moments of suspense when it appears they might fail.

After Rififi, heist scenes got longer and more intricate. The one in Big Deal on Madonna Street runs twenty minutes, those in Seven Thieves and The Day They Robbed the Bank of England run thirty minutes, and those in Topkapi and The Italian Job approach forty minutes. To motivate these long, virtuosic passages, there need to be many obstacles, many ingenious ways around them, and many characters concentrating on their assigned duties.

Long or short, the heist can be shifted off-center. The heist can be the climax, as in The Big Caper, or it can be virtually the film’s entire second half, as in The Italian Job (which arguably doesn’t complete the heist and so never provides a proper aftermath). Topkapi’s flamboyant robbery, involving elaborate subterfuges, dominates the film’s latter stretches, leading to a quick reversal in its epilogue. The heist is finished early on in The Lady Killers, since the crucial action is the long aftermath in which, contradicting the title, the crooks dispose of one another. By contrast, the heist dominates nearly all of Larceny, Inc. Most of the film is devoted to the crooks’ slowly deepening tunnel, as the process is interrupted by breaks in the water main, a geyser of furnace oil, and their decision to abandon their plan in favor of going straight—before another crook comes along to continue the caper.

Or the heist can launch the film. In Plunder Road, after the train robbery is completed, the rest of the film is the aftermath, consisting of chases and suspense sequences. The circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases are alluded to in dialogue, as suits a low-budget production. The plot of Touchez pas au grisbi starts the morning after the caper and shows thieves trying to protect their loot from a treacherous drug dealer. It was probably inevitable that somebody would make a heist movie that keeps the heist offscreen and makes the action one long aftermath.

Steering the moving spotlight

Topkapi (1964).

Many films based on mystery rely on restricting a character’s range of knowledge, as in detective novels told in the first person. But suspense, Hitchcock and others recognized, relies on greater access to story information. If there’s a bomb under the table, Hitch advised, tell the viewer but don’t tell the characters. The heist film, as an account of how a crime is committed, depends more on suspense than mystery. So we’d expect a constant shuttling from character to character, filling us in on how the scheme is going and letting us worry about impending dangers.

This is generally what we find. Criss Cross is unusual in confining us to what Steve knows about Anna’s and Slim’s real agendas, and this confinement is what yields the surprises that pop up in the film’s final stretches. Mostly, though, heist movies and novels use omniscient narration. Employing what I call in Reinventing Hollywood the “moving spotlight” approach, the film shifts us from attachment to one character to another.

The moving spotlight permits us to understand the choreography of the crime, in which many characters play a part, and to feel suspense when matters of timing or accident intrude. Indeed, the convention of the unforeseen accident that spoils the heist relies on our breaking attachment to the crooks and getting privileged access to the off-schedule night watchman, the passing witness, or the failed piece of machinery. In Topkapi we and not the thieves learn how a stray bird will upset their getaway.

This omniscient narration (which need not tell us absolutely everything) can be deployed in a range of ways. One option is chapter titles, as in Big Deal on Madonna Street (and revived by Tarantino in Reservoir Dogs). A more common resource is the non-character narrator, present as an authoritative voice-over. In Bob le flambeur, a worldly male voice introduces us to Bob’s daily routine and comments somewhat cynically on his place in his milieu.

A similar all-knowing voice introduces us one by one to the heisters in The Good Die Young; there it eases the transition into expository flashbacks. Topkapi treats this convention, as others, with self-conscious playfulness. At the beginning the beguiling woman in the gang addresses the camera and explains that the heist aims to get the emerald she covets. She doesn’t take this narrating role again until the very end, in a brief epilogue that replays the gathering of the gang in stylized form.

Heist films must often choose whether to widen the field of view to include either the cops or civilians. Armored Car Robbery (1950), for me a peripheral instance of a heist film, alternates the gang’s activities—which do pass through the phases I’ve outlined—with the detectives’ investigation. The result is balanced between heist film and police procedural. Something similar happens in Violent Saturday (1955), which devotes most of its plot to a gang’s scheme to rob a mining town’s bank. Crosscut with the gang’s gathering and planning are scenes showing several members of the community, each with domestic problems. These scenes, typical of small-town melodrama (dissolute rich people, sexy nurse, repressed librarian, lovelorn bank manager), not only pad out the film but show us characters who will be affected by the heist. Some become witnesses and bystanders during the robbery, one is killed, and one, a local mining manager, will be forced to fight the gang at the climax.

The timing and selection of the shifts among characters can build up specific effects. For instance, in Big Deal on Madonna Street, the heist is conceived by Cosimo, a hardheaded crook doing time. A handful of would-be crooks decides to execute the robbery without him. We know, as the gang does not, that he has been released and is conspiring to interfere. The filmmakers could have made Cosimo’s return a surprise revelation, but instead our expectation that he’ll start meddling intensifies our interest.

Similarly, we know, as the Topkapi gang does not, that Arthur is a police spy. But then he confesses to them, so we know, as the Turkish police do not, that he is to be a double agent. The film milks suspense during the scenes in which Arthur relays information to the authorities, and then it makes us wonder how the gang will use their new knowledge of police surveillance. This is the sort of fine-tuned choice about “who knows what when” that heist films must make at every turn.

At a more granular level, when the spotlight is on one character, the filmmakers must choose whether to make those moments, shot by shot, highly restricted or not. In The Killers, Nick Adams’ account of Ole’s reaction to the stranger stopping for gas is more or less plausibly limited to Nick’s ken. But the precise exchange of glances between the driver and the Swede signal to us that Ole has been recognized. Nick doesn’t register this, since he’s standing at the rear of the car (barely visible in my first still, over Ole’s right shoulder).

In effect, this is a narrational aside to the audience. Nick can’t see this significant exchange of glances, and his voice-over doesn’t specify it, so we can’t assume Riordan learns of it. But this privileged moment primes us to see Big Jim as a major menace in scenes to come. This sort of deviation from what a character could plausibly know or notice is common in cinematic narration and differentiates it from literary narration, which is more tightly restricted in handling “point of view.” Classical Hollywood is biased toward unrestricted narration; radical restriction is rare. The heist genre can exploit many fine gradations between attachment to a character and more wide-ranging knowledge.

What’s our clock?

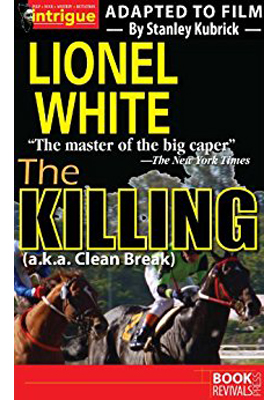

The Killing (1956).

As we’ve seen, two early instances of heist films break with a linear layout of the story. Criss Cross presents what Reinventing Hollywood calls a crisis structure, beginning just before the turning point and flashing back to show what led up to it. The Killers has a refracted narration, with all of the past events passed to the investigator Riordan and us through witnesses’ testimony. The flashbacks in Criss Cross are chronological, but those in The Killers are drastically out of order.

Time-scrambling, then, seems to be especially welcome in the heist film (as not, say, in the Western). The basic plot pattern is such a simple one that shuffling phases or parts of phases doesn’t create confusion. Yet few films of the 1950s I’ve found display the complexity of the Forties examples. Indeed, a time-juggling heist novel, The Lions at the Kill (Simon Kent, 1959) was ironed into straightforward linearity in the film version, Seven Thieves.

The Good Die Young displays a more complicated structure. It begins at a point of crisis, with four men driving in a car to the site of the caper.

The voice-over narrator introduces each man in turn, and then a long flashback explains his backstory. Deprived of information about the heist, we have to wonder how the narration will bring the men together and create their plan.

After the long section explaining each man’s circumstances, all involving women and money, the flashbacks meld. The men gradually come to know each other through frequenting the same pub. Their desperation pushes them toward accepting one man’s proposal that they rob a post office. With so much time spent on preparation and assembly, the actual planning is necessarily brief. Eventually the final flashback flows seamlessly into the present-time situation, initiating a brief replay of the dialogue in the car that opened the film. The heist (devolving into a disastrous gun battle) initiates the climax, and an airport aftermath concludes the film.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

On the day of the robbery, White’s narration again attaches itself seriatim to each man as he executes his role in the scheme. While the early part of the book had a few mild jumps back in time to follow each heister, the day of the job creates extreme back-and-forth shifts. We follow the bartender, for instance, going to the track on the fateful day, before the next subchapter skips back to the cashier waking up and then going to the same train. In a later section, we skip back to the previous day and attach ourselves to the sniper who will shoot the racehorse. Because of the overlapping lines of action, the shooting of the horse and the starting of the bar fight are presented twice. Everything eventually converges on Johnny Clay, the mastermind, who breaks into the money room and steals the day’s revenue.

These temporal overlaps emerge partly from the description of the action, but they’re also marked by either characters looking at clocks or watches, or by explicit mention in the prose, such as “It was exactly six forty-five when…”

The film version makes these overlapping schedules much more explicit. A detached voice-over describing police routine or criminal behavior had become a commonplace in the 1940s, in both “semidocumentary” films and in radio drama, notably Dragnet. In The Killing, apart from lending an aura of authenticity, the voice-over exaggerates the time markers of the novel by introducing scenes crisply. The first five scenes are introduced with these tags:

“At exactly 3:45…”

“About an hour earlier…”

“At seven PM that same day…”

“A half an hour earlier…”

“At 7:15 that same night…”

These lead-ins remind us of the ticking clock, set up parallels among the characters, and get us acclimated to the film’s method of tracking one character, then jumping back in time to track another. This is moving-spotlight narration on markedly parallel tracks. The same method will be applied during the heist, when ten consecutive scenes and several others will be tagged in the same way. (“Mike O’Reilly was ready at 11:15.”)

It’s not just the repetitions that exaggerate White’s jagged time scheme. When the sniper Nikki is shot after plugging the racehorse, the narrator reports drily: “Nikki was dead at 4:24.” Cut to Johnny leaving a luggage store, and the voice-over announces: “At 2:15 that afternoon Johnny Clay was still in the city.”

The time jumps more or less buried in White’s prose are made dissonant in the film. Here the juxtaposition heightens the likelihood that Johnny’s robbery won’t go according to plan.

The replays are no less sharply profiled. As the scenic blocks move from character to character and skip back in time, they include actions we’ve already seen. The most persistent is the repetition of the track announcer’s calling the start of the crucial seventh race, but we also get replays of the wrestler Maurice starting a fight, the downing of the horse, and glimpses of Johnny waiting to slip into the cash room.

Instead of shuffling flashbacks in the manner of The Killers, The Killing offers brief time chunks stacked in slightly overlapping array until they all square up in a single moment, the consummation of the robbery. This structure allows for the sort of character delineation we find in The Asphalt Jungle while also offering the audience a formal game to enjoy. Kubrick’s film can be seen as pointing in two directions—revising the flashback format of the 1940s entries, but becoming a point of reference for later filmmakers eager to innovate games with time and viewpoint that would remain comprehensible to the audience.

The Killing helped make Clean Break White’s most famous novel. It was often republished under the film’s title. Perhaps in a grateful spirit White’s 1960 novel Steal Big (1960) included this scene.

Donovan didn’t look at the half-dozen worn, barely legible signs in the dingy lobby of the building. He went at once to the elevator and asked for the fifth floor. Getting out of the elevator, he turned left, took a dozen steps and knocked on a pebbled-glass door. The door bore the legend, KUBRIC NOVELTY COMPANY.

Mr. Kubric, it turns out, supplies illegal guns and explosives.

Art for artifice’s sake

Inside Man (2006).

White’s in-joke, along with The Killing’s gamelike approach to structure, reminds us that whatever its claim to realism, this is a highly artificial genre. The strict template and the ritualistic steps in it—recruiting the crew, casing the target, checking watches—invite filmmakers to tinker with self-conscious narration that lets the viewer in on the joke.

One convention, that of the rehearsal for the big job, is flaunted in Bob le flambeur, when the narrator simply breaks into the film with the line, “Here’s how Bob pictured the heist,” and we get a stylized, hypothetical enactment of the job carried off perfectly. In these films, when the rehearsal goes well, you know the real thing will face problems.

Something similar, though suited to light comedy, takes place in Gambit. Here we think we’re seeing the heist as executed (across twenty-three minutes), but it proves to be no more than the fantasy of the crook hatching it. Again, everything that succeeds in the fantasy goes wrong in reality.

As it gained a profile, the genre got reflexive. In the novel that was the source for The League of Gentlemen, the heisters explicitly model their plan on the one in Clean Break. The film version likewise sets its heisters mimicking a pulp novel, though it didn’t specify the title. And in The Wrong Arm of the Law (1963), Peter Sellers’ cockney mastermind promises to show his henchmen “educational films and training films” like Rififi, The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, and The League of Gentlemen.

The opportunities the genre provides for experimenting with story stratagems, sometimes in very self-conscious ways, seem to have been part of the reason later filmmakers tried their hand at it. In the 1990s and 2000s, writers and directors drawn to neo-noir and narrative experiment took up thriller conventions generally, and the heist film was one option.

In Reservoir Dogs (1992), Tarantino revived the shuffling of time and viewpoint that was ingredient to the genre. Although the film pays homage to Clean Break, its form is no less indebted to Criss Cross. Like that film, it flashes back from the day of the heist in order to run through the canonical phases of action. And as in The Killers, those phases are scrambled out of order. Brian Singer’s The Usual Suspects (1995) brings the (very ‘40s) device of the lying flashback to the genre, within the template of police questioning after the heist. Inside Man (2006) mixed to-camera narration, flashbacks, and flashforwards to interrogations after the crime.

Among Americans it’s Steven Soderbergh who has returned to the caper film most frequently. The Underneath (1995) is a remake of Criss Cross, with an extra layer of flashbacks. Logan Lucky (2017), with its deadpan redneck losers, joins the tradition of comic heist movies. Most strikingly, the Ocean’s series makes a virtual fetish of the male camaraderie and playful plot tricks typical of the genre. The films pepper the action with voice-overs, cunning ellipses, and flashbacks within flashbacks. The plots hide key information about the plan. They fill the action with in-jokes, such as a star cameo by Bruce Willis commenting on box-office grosses. Like 1960s films, they incorporate romantic comedy. In Ocean’s Eleven ((2001) Danny and Tess arrange a post-divorce reconciliation, and in Ocean’s Twelve (2004) Danny’s pal Rusty gets involved with police agent Isabel.

Piling up obstacles, reversals, bluffs, and double-bluffs, the films form a kind of anthology of the genre’s tricks. By the time we get to Ocean’s Thirteen (2007), the early phases of the standard plot schema can be given short shrift. We know the gang and its modus operandi, so the bulk of the film becomes a mind-bogglingly intricate heist including everything from planting bedbugs in a hotel room to manufacturing loaded dice in a Mexican factory under threat of strike. The network of rules and roles laid out in the 1950s—master mind, aged expert, financier, crooked helpers, allies and rivals and go-betweens and stooges—are given baroque elaboration and treated with an almost self-congratulatory panache.

So am I looking forward to Ocean’s Eight? It’s directed by Gary Ross, so I don’t expect Soderbergh’s casual sheen. And the target of the heist, a fashion show at the Met, may be a bit too on the nose; why can’t the ladies tackle a payroll or a munitions factory? Still, like a butterfly collector looking for new specimens, I’m quite curious. When it comes to narrative strategies, I’m a sucker for a fresh con.

Thanks to Jim Healy and Geoff Gardner for discussion of the genre.

Stuart Kaminsky’s American Film Genres: Approaches to a Critical Theory of Popular Film (Plaum, 1974) is a trailblazing study, and the chapter on the “big-caper” film is an indispensible starting point for studying this kind of movie. Later editions of the book eliminated this chapter. A wide-ranging recent survey is Daryl Lee’s The Heist Film: Stealing with Style (Wallflower, 2014). Alastair Phillips offers an in-depth analysis of a classic in Rififi (Tauris, 2009).

My quotations from Donald Westlake come from Murderous Schemes: An Anthology of Classic Detective Stories (Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 1 and 126. I also found the entry on Lionel White in Brian Ritt’s Paperback Confidential: Crime Writers of the Paperback Era (Stark House, 2013) helpful. The “KUBRIC” passage in White’s Steal Big (Fawcett, 1960) is on p. 47. White much influenced Westlake, as I hope to show in a future entry, but Westlake was a far superior stylist, as I discuss a little in this entry. See also this note on Levi Stahl’s anthology of Westlake nonfiction.

For more on analyzing narrative see “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” and “Understanding Film Narrative: The Trailer.” Tarantino’s debts to the 1940s are reviewed in this entry. See as well my recent entry on thrillers. I analyze the convoluted narrative of The Killers in Chapter 9 of Narration in the Fiction Film. The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies discusses 1990s filmmakers’ relation to the Forties. Multiple-protagonist plotting is considered in Chapter 3 of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The concept of schema and revision is considered here as applied to style; this entry, like Reinventing, applies it to narrative principles. My Dunkirk entry points out affinities between the overlapped time frames in The Killing and the three-track scheme Nolan gives us. Unlike Kubrick, Dunkirk applies the principle to the entire film and assigns each timeline a different duration, but it generates a back-and-fill organization and clusters of replays reminiscent of The Killing.

Burt Lancaster is considered here, and why not?

P. S. 26 March 2020: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correcting two slips in my account of Criss Cross!

Ocean’s Eight (2018).