Wednesday | October 5, 2016

The Red Turtle (2016).

Kristin here:

Recently this blog passed its tenth anniversary. Our first modest entry, on Christine Vachon’s book A Killer Life, was posted on September 26, 2006. The second was “A film festival for all seasons,” the first of David’s five reports on that year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, where he was a judge in the Dragons and Tigers competition for young Asian directors. Since then we both have come to VIFF nearly every year. Its organizers and staff are always welcoming and we can see lots of films in a relatively relaxed atmosphere free from the red carpets, the markets, and the celebrities that make some of the bigger festivals difficult to navigate. We’re delighted to be back in Vancouver now, reporting on its rich array of offerings for a tenth time.

The Rehearsal

Canadian-born, New Zealand-bred, New York-dwelling director Alison Maclean gives us The Rehearsal (2016), her first feature since her best-known film, Jesus’ Son (1998). In between she has been primarily working in television, including episodes of Sex and the City and The Tudors.

The film begins with an image of an Asian woman in a blonde wig and ultra-high-heel shoes facing directly into the camera and miming a tennis game (see bottom). Such an arresting opening is a wise move, since the film’s early portions are mostly expository. The opening introduces Stanley, a young Maori man who gains acceptance to a high-pressure, prestigious drama school, despite his apparent lack of the necessary talent and drive. Overcoming his initial listlessness, Stanley gradually bonds with his classmates. He also blossoms somewhat under the tough-love approach, sometimes verging on cruelty, that is the policy of Hannah, the demanding head of the school (Kerry Fox, above, best known for playing Janet Frame in An Angel at My Table).

The opening image turns out to be a flashforward to a rehearsal of an original playlet that Stanley and a group of teammates must put on at the end of the school year. For their story they seize upon a current local scandal in which a tennis coach has had an affair with an underage pupil. Stanley has begun dating the girl’s sister Isolde, which gives him knowledge about the situation that the group incorporate into their play. The main suspense arises from Stanley’s failure to tell Isolde what his team is up to, despite the fact that inevitably she will find out. More drama arises from the effects of Hannah’s harsh methods on the students, particularly Stanley’s vulnerable roommate.

The Rehearsal currently has no American distributor but will play on October 5 at the New York Film Festival.

The Confessions (Le Confessioni)

Early in The Confessions a spectacular drone shot follows a moving car from above the treetops. Eventually the car arrives at a driveway crowded with news photographers, and the camera leaves it to reveal a huge modern hotel and then move beyond it over ta body of water. Though not as flashy, the rest of the film has the sort of lush cinematography (above) and rich musical score that are familiar from such other recent prestigious Italian productions as The Great Beauty.

The plot involves a sort of bitter parody of a G8 meeting, with eight representatives of major countries meeting under the guidance of the head of the International Monetary Fund. They are preparing to execute some sinister plan, under the guise of “creative destruction,” that will solve a current international financial crisis in a way that will benefit rich countries at the expense of the poorest ones. Daniel Roché, the head of the IMF, has also invited an Italian monk, Roberto Salus (played by Tony Servillo, so memorable in The Great Beauty and especially Il Divo), to attend.

The reason for Salus’ presence is not clear, though Roché requests him to hear his first confession in twenty years. Roché is soon found dead. It’s apparently a suicide, but some of the finance ministers attending the meeting seemingly try to eliminate Salus by casting him under suspicion of murder. The film turns into a cat-and-mouse game, with each seeking out Salus for devious conversations, punctuated with tantalizing flashbacks that gradually reveal what Roché had revealed during the confession scene.

Although on the surface the film seems to be developing into a thriller, it is too playful to be taken entirely seriously, and the wise, reserved Salus always delivers the final sardonic comic topper in his exchanges with each of the villains. There is even a suggestion of a sort of magical realism at a few points. Ultimately The Confessions is a somewhat uneasy mixture of genres but a highly entertaining one.

The Red Turtle

In the early days of the blog (December 10, 2006), I wrote an entry claiming that in contemporary cinema, animated films are on average more likely to be stylistically superior to live-action ones. Animated films have to be intensively pre-planned, including recording soundtracks in advance. Such careful preparation, which eliminates the easy reliance on “coverage” and limits changes in post-production, imparts a rigor and care that are too often missing in live-action features. Two experiences with animated films here at Vancouver reinforce my point.

David and I agree that The Red Turtle is a standout among the films we’ve seen so far. It’s an animated feature by Michael Dudok de Wit, the Dutch animator who won the animated-short-film Oscar in 2000 for Father and Daughter. The Red Turtle won a Special Jury Prize at Cannes this year. It also has Studio Ghibli’s name attached, which might lead to some raised eyebrows.

Studio Ghibli’s three legendary animators all retired in recent years: Hayao Miyazaki, after The Wind Rises (2013); Isao Takahata, after The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013); and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, after When Marnie Was There (2014). Rumors that the studio would shut down fortunately proved false, despite the fact that its crew of animators was disbanded. The Red Turtle is the first film to bear the Studio Ghibli name since Marnie. The studio, not Dudok de Wit, initiated the project, and perhaps it will henceforth support occasional hand-picked productions like this one.

Though The Red Turtle uses traditional cell animation, it does not particularly imitate the studio’s familiar style Nevertheless, the film is far from being a radical departure from its previous output. For one thing, The Red Turtle is vitally concerned with the depiction of nature. It opens with a storm that drives a single survivor from a shipwreck onto the beach of a small island, uninhabited by humans. His first contact with living things there comes when a curious sand-crab crawls up his pant-leg, and a group of these crabs provides touches of comic relief throughout.

Three times the unnamed man tries to escape aboard bamboo rafts (above), but each time a large red sea turtle destroys his craft (see top) and forces him back to the island. In the story’s first fantastical event, the turtle transforms into a woman, and the two soon fall in love, Adam and Eve in a sparse Garden of Eden. They gain a son, a tsunami introduces a note of threat into the idyllic depiction of nature, and ultimately they face mortality. The simplicity and fantastical elements of the story would be perfectly convincing as a rendition of an existing myth, but the story is completely Dudok de Wit’s invention.

The three human figures are drawn very simply and look like they were rotoscoped, though I can find no confirmation of that online. The depiction of the natural landscape and the creatures that inhabit it are, however, stunningly beautiful. Without attempting a photorealistic look, Dudok de Wit’s team have captured the look and movement of sunlit seawater, the rhythmic rustling of leaves, and even the differences in color between the exposed and the submerged surfaces of woolsack blocks of granite at the ocean’s edge. It is almost as if they have managed to rotoscope all of nature.

The classic films by the main directors at Studio Ghibli are more elaborate and complex than The Red Turtle, but the new film suggests that the studio will maintain its high standards in its future productions.

The Red Turtle was bought by Sony Pictures Classics and is scheduled for a mid-December American release.

Window Horses (The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming)

While The Red Turtle is a high-profile animated film, Window Horses originated as an Indiegogo project. Its success in that campaign led Sandra Oh to back the film, signing signed on as a producer and providing the voice of the film’s heroine. The project gained additional support, including by the National Film Board of Canada. Still, it is likely to remain largely a festival item (it premiered at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival), with only a limited theatrical release in Canada early next year. (Information on that release is not yet available online, but news will presumably be posted on the film’s website.) It exhibits a lively imagination and stylistic sophistication that deserve a wider audience, which with luck it will achieve via streaming.

The story centers on Rosie Ming. With her Chinese mother dead and her father having apparently abandoned his family to return to Iran, she lives in Vancouver with her maternal grandparents. A self-published book of her verses leads to an invitation to a poetry festival in Shiraz. Donning a full chador in the hopes of fitting in, she finds herself surrounded by women wearing simple scarves and vibrant clothing.

The animation itself is colorful, with stylized faces that are vaguely reminiscent of Picasso (as in the tour-bus scene, above). Rosie stands out in her utter simplicity, rendered as a black-clothed stick figure with a round, white face sketched in only by eyes and, when she speaks, a mouth. Recitations of poems are accompanied by scenes of animation is a variety of styles, contributed by such animators as Kevin Langdale, Janet Perlman, Bahram Javaheri, and Jody Kramer.

Overall, it is an engaging and entertaining film, showing how much an independent filmmaker can do with limited means. In that it reminds me of Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues.

Films that have particularly impressed us so far include Pablo Larrain’s Neruda (playing again on October 9), Cristian Mungui’s Graduation (playing again October 5 and 11), and above all Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion (playing again on October 9). We’ll be blogging about these and others over the next several days.

The Rehearsal (2016).

Posted in Animation, Festivals: Vancouver, Film comments, National cinemas: New Zealand |  open printable version

| No Comments » open printable version

| No Comments »

Sunday | September 25, 2016

Sully (2016).

What happens in the Forties doesn’t stay in the Forties. That’s one motto of the book I’ve just finished on Hollywood storytelling in the period 1939-1952. The argument is that several narrative conventions that crystallized in that era became part of the Hollywood tradition and continue to shape the films of today.

I say “crystallized,” not “suddenly appeared,” because in general terms every significant technique I pick out has precedents in earlier years of American filmmaking. Forties filmmakers didn’t invent flashbacks, voice-over narration, dream sequences, and the like. What Forties writers and directors did was consolidate those techniques into major norms. They went on to explore, sometimes with startling delicacy, the techniques’ range and power.

This pattern of scattered invention, followed by consolidation and refinement, isn’t uncommon in the history of technology. The computer mouse was devised by several companies and individuals, but it became ubiquitous in the 1980s thanks to Microsoft and Apple. What historians call the diffusion phase of change created a foundation for future development.

The same sort of diffusion sometimes takes place in cinematic form and style. For example, flashbacks in the 1930s were fairly rare and, except for The Power and the Glory (1933) and a few other films, fairly perfunctory. They simply filled in information that had been suppressed earlier, usually providing the solution of a mystery. During the 1940s, when flashbacks became more widely used, filmmakers were obliged by the pressures of competition to explore the technique’s finer-grained possibilities, as in Kitty Foyle (1940), Citizen Kane (1941), Lydia (1941), and many other films.

Once a technique becomes common, and refined in its usage, later filmmakers can treat it as a taken-for-granted option. It seems likely that the development of flashbacks in the 1940s, in both American and other cinemas, laid the groundwork for efforts like Hiroshima mon amour (1959). American filmmakers reworked flashbacks in creative ways in Petulia (1968), They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), and other films influenced not only by 1940s Hollywood but also by 1950s and 1960s European cinema.

Call me biased, but now nearly every mainstream movie I see seems indebted to storytelling strategies consolidated in the 1940s. Take Sully. In less than ninety minutes, it runs through a wide range of narrative techniques. The fact that we take them so completely for granted, and understand them so swiftly, indicates the stability of what we call a Hollywood movie. It’s kind of miraculous that filmmakers continue to find ingenious ways to fulfill norms that were locked into place seventy years ago.

Clint the classicist

American Sniper (2014).

Before I get to Sully, let’s pause on other recent films directed by Clint Eastwood. (Yes, spoilers will be involved.) They illustrate just how fully narrative techniques associated with the 1990s-2000s have become mainstream resources. Although those techniques are largely revisions of possibilities crystallized in the 1940s, most people know them in their modern guise. Today’s audiences are more familiar with the intricately out-of-order flashbacks of The Prestige (2006) than those found in The Killers (1946) or Backfire (1950).

Hereafter (2010), written by Peter Morgan, lays out three story lines. A French TV journalist, after nearly drowning during a tsunami, is convinced she has had a vision of the afterlife. A London boy yearns to contact his dead twin. An American construction worker, as a result of perilous childhood surgery, has acquired the gift—or, as he says, the curse—of being able to communicate with the dead. Each protagonist’s experiences are treated as separate blocks, crosscut ever more swiftly, until the three converge at a London book fair. The American helps the boy contact his brother, and by meeting the journalist, who has written a book about her research into the hereafter, begins to feel he can rejoin the world.

Hereafter is what I’ve called a network narrative: a plot centered on several more or less equally weighted characters with independent goals. Their fates intertwine by chance (or fate). In the 1930s and 1940s, network plotting tended to be confined to a locale or vehicle, typically in a Grand Hotel situation. More dispersed and numerous story lines emerged with Altman’s Nashville (1975), though even that has a circumscribed time limit. During the 1990s and 2000s, both spatially confined versions and more free-ranging ones became quite common in filmmaking across the world. Hereafter revives the strategy, tying the parallel plotlines to a conception of a realm after death.

Hereafter’s second primary expressive option involves flash-cut visions of the afterlife—blurry, distorted images that give only a glimpse of what Marie the journalist and George the medium “see.” These aren’t sustained, so that, for instance, when George relays to someone what the departed is saying, the film stays objective, simply presenting George’s report on what he’s being told.

This reticence about showing us the Beyond allows us to reflect that at one crucial moment, perhaps George is improvising the advice that he claims to be passing along to the dead boy’s twin.

In a final twist, George’s curse changes to something more like a gift. When he manages to arrange a rendezvous with Marie, his vision of the afterlife is replaced by precognition in this world. Now his vision, clear and sustained, shows him kissing her. Or maybe he’s gained access to normal wish fulfillment.

In either case, the Hollywood clinch gets re-motivated.

Jersey Boys (2014) presents the rise of the Four Seasons, with emphasis on the lead singer, high-pitched and high-strung Frankie Valli. Although the bulk of the film takes place in the 1950s and 1960s, it climaxes with the group’s reunion at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990.

A common option would be to start at the reunion and then flash back to trace the group’s rise. Instead, the film roughly follows the layout of Marshall Brickman’s and Rick Elice’s book for the Broadway show. That presents the ups and downs of the group’s career chronologically, with each member narrating a block of scenes. In the stage version each block is labeled, cutely enough, with a season, from ebullient spring to doleful winter, with an extra-seasonal epilogue at the Hall of Fame.

The film version, also scripted by Brickman and Elice, doesn’t flag the seasons but does incorporate round-robin narrators. In the film’s opening Tony DeVito introduces us to the neighborhood and the formation of the group.

Later, singer-composer Bob Gaudio (above) and bass guitarist Nick Massi comment on stretches of the group’s rise and fall. They feel free to criticize each other, as when Nick says the trouble began well before Bob thought. These narrating moments are handled through to-camera address: each Season looks straight at us, explaining what’s happening, or just happened, or is about to happen.

Again, to-camera address can be found throughout film history, but the Forties made it salient by letting it bracket the entire film, often as the present-time frame for a flashback (Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, 1948; Edward, My Son, 1949; Young Man with a Horn, 1950; below). It’s rarer to have the narrator interrupt an ongoing scene, turn toward us, and break the fourth wall, but we do find it in My Life with Caroline (1941, below).

The Caroline device was revived in other films, notably Alfie (1966) and much more recently The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). The tweak that Jersey Boys introduces is the fact that the narrator uses the past tense to describe the scene he’s in–an occasional option in The Big Short (2015) too.

The tag-team narration in Jersey Boys doesn’t create sharply distinct blocks, in the Rashomon manner. Each singer’s segment roams pretty freely among other characters’ doings, so there’s no strong attachment to a single viewpoint. But some variations crop up. Frankie is the most minimal narrator. He never turns to the camera to address us, and we hear his voice-over comments only once in “his” stretch of the film. Perhaps that’s because he’s the character whose personal life is most crucial to the plot, and we see everything he’s up to. (Hollywood group protagonists often adopt a “first among equals” principle.) And at the final reunion, each of the quartet turns from the microphone to address us in quick succession, summing up their view of what’s happened. In Jersey Boys, as in Hereafter, some long-standing conventions are given moderately original handling.

American Sniper (2014) is the most linear and traditional of this batch, except for one tactic that becomes more important in Sully. The opening sequence shows sniper Chris Kyle perched atop a building scanning the Falluja neighborhood for enemy action. He sees a woman and child walking toward the Marine convoy, and she passes the boy what becomes visible as a grenade.

Chris must decide whether to fire. We then flash back to Chris as a boy shooting a deer and being told by his dad: “You got a gift.” There follow scenes tracing his childhood and young manhood, and his response to militant bombings of U. S. embassies: joining the Navy SEALS. At his wedding, he’s called to the invasion of Iraq.

This flashback, which consumes most of the film’s first “act” (ending about 25 minutes in), is followed by a return to the moment of decision on the rooftop. To prolong the suspense, the film replays Chris’s spotting of the woman and child with the grenade. He fires and kills both.

This tactic, of coming out of a flashback with a repetition of what initiated it, is yet another storytelling choice we find emerging in the Forties. One clear example is the framing of the long central flashback of Body and Soul (1947). The opening scene shows an eerily empty training camp before boxer Charley Davis wakes up from a bad dream and cries, “Ben!”

A fairly lengthy setup in the present follows before we get a long flashback tracing Charley’s career. At the conclusion of the flashback, again we see the shot of the camp, and again we see Charley awakening. A match-on-action cut takes us from that to the point where the frame story stopped: him lying on the table in his dressing room, just before the big bout.

The return to the camp has buckled the flashback shut in a way similar to the return to the Falluja roof in American Sniper.

The device of the reiterated flashback is developed more unusually in Eastwood’s J. Edgar (2011). The film follows a classic norm for the biopic: In old age, the central character recalls his or her life. Those flashbacks could be motivated as private memory, or as episodes recounted to someone. And in the Forties, that someone was often a reporter or transcriber, as in Edison the Man (1940) and The Great Man’s Lady (1942). If you count Citizen Kane (1941) as a fictional biography, then Thompson fulfills the role of listener.

In J. Edgar, the self-important Hoover has assigned FBI agents to take down his memoirs. Flashbacks inevitably follow. As the film goes on, the narration wedges in “unofficial” flashbacks, mostly scenes with Hoover’s life partner Clyde Tolson, and these are justified as purely private musings.

What’s interesting is that some material Hoover dictates proves unreliable. At the climax Tolson, who has read the manuscript, denounces it as a tissue of lies. We then get repetitions of key scenes from the dictation, all of which show that Hoover wasn’t involved in cracking the big cases he took credit for. The film decisively debunks Hoover’s myth that he was not only a superb administrator but also a heroic, hands-on field commander.

The lying flashback is yet one more minor convention of 1940s cinema. For those who haven’t seen the most important example, I’ll refrain from mentioning the title, but let Thru Different Eyes (1942) and Crossfire (1947) stand as examples. (At one phase of production, Laura, 1944, was planned to have a lying flashback too.) The replay emerges as a way to correct the first impressions.

In tracing precedents for these storytelling choices, I don’t mean to criticize them as unoriginal. The screenwriters of Jersey Boys and Hereafter, along with Jason Hall (American Sniper) and Dustin Lance Black (J. Edgar), are drawing upon models that have been circulating in Hollywood filmmaking for decades, and that became particularly salient in the 1990s and 2000s. These scripts are also revising the techniques in ways that seem to me original to some degree.

As for Eastwood, he’s said to “shoot the script,” so perhaps these more or less up-to-date narrative techniques are brought into his work through the screenwriters. But he’s also often called one of the last “classical” directors. Partly, I think, that’s a reference to his style: his fondness for establishing shots of buildings, shots of people arriving in cars or driving away, shot/reverse-shot dialogue exchanges, and unobtrusive Steadicam. In Jersey Boys, the musical numbers seem rather haphazardly put together, but Eastwood is cogent in developing action sequences, as the firefights in American Sniper show.

It’s not just a matter of style, though. To some extent the narrative strategies I’ve mentioned here have become part of today’s “classical Hollywood filmmaking.” Flashbacks, block construction, replays, to-camera address, network narratives, and bursts of subjectivity are so ingrained in contemporary filmmaking that we might want to think of Hollywood storytelling as a constantly expanding menu that discovers new flavors in traditional ingredients. The basic premises of classical narrative permit an indefinitely large range of variation, both large-scale and fine-grained.

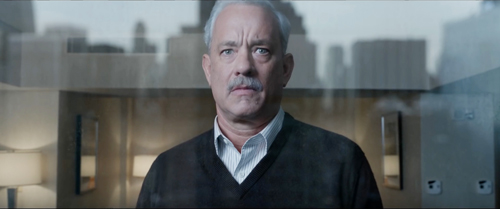

Not a crash, a water landing

Most flashbacks present new information, either in a large block, as in Body and Soul, or in bits, as in J. Edgar. Other flashbacks present old information, mostly to remind us of something we’ve already seen or heard that’s relevant to the moment. Occasionally, a flashback is both a reminder, because it shows us something we’ve seen before, and a source of new information. It’s very common for mystery films and TV shows to use a flashback to an earlier scene in order to fill in whodunit, and how it was done.

Let’s call this reminder involving new information a replay. A replay goes beyond a simple repetition by showing the action in a new light—from a different character’s perspective, or including information that was omitted on the first pass. The latter happens in J. Edgar, when we see earlier scenes corrected to give credit to the actual agents involved.

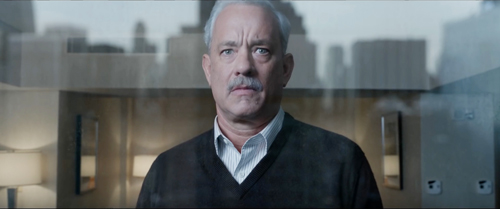

Replays and other techniques of repetition are given a remarkably central role in Todd Komarnicki’s screenplay for Sully. It’s not surprising because the core incident, Chesley Sullenberger’s landing of a damaged airliner on the Hudson River, is said to have consumed only 208 seconds. There would have been many ways to tell this story; a straight linear account, as in United 93 (2006), must have been a tempting option. Instead, Sully concentrates on the heroic pilot, whose action was supported by comradeship with his co-pilot, and the collective spirit of the passengers, crew, and first responders. In order to add conflict, Komarnicki and Eastwood build up the drama of the National Transportation Safety Board’s inquiry into the landing. The members of the board are initially presented as skeptical antagonists, although by the end, they gracefully acknowledge that the plane could not have returned to the nearest airfields.

The emergency landing is presented in flashbacks, framed by the ongoing investigation. But the film opens with the plane crashing into Manhattan skyscrapers.

It’s revealed as Sully’s nightmare, which haunts him after the rescue. The sequence anchors us firmly in his consciousness; we’ll be more attached to him than to any other character. As an anxiety dream, it presents a sort of what-if version that retrospectively justifies his decision to land on the Hudson. But its emotional tenor reveals his consistent worry throughout the plot that the authorities will judge that he put the passengers’ lives at risk unnecessarily.

Later another version of this Manhattan crash plays out not as a dream but as a waking fantasy, as Sully looks out of a skyscraper window. The scene suggests that he’ll never be able to see this cityscape without imagining the catastrophic alternative scenario. The same fraught feelings crop up in another fantasy passage, when he imagines a TV commentator asking: “Sully: Hero or fraud?” It isn’t just the accusation from outsiders that worries him. He questions what he’s done too. It’s important that the film give Sully enough self-doubt to build our sympathy and to make his final vindication all the more deserved.

Having given us dream and daydream, the filmic narration also gives us memory, in the form of flashbacks to Sully’s younger days, when he fell in love with flying and graduated to testing aircraft in dangerous situations. These affirm his expertise while also showing the quiet determination that can seem a little dour. (He’s told by his flight instructor to smile more.) This serious older man was also a serious young one.

From the start, the Board’s inquiry sets up the need for simulations to check Sully’s decisions. The first set are computer-based, and Sully requests that pilots also execute simulations. The human simulations will become crucial points of conflict at the climax.

One of Sully’s phone calls to his wife back home triggers the first flashback to the fateful day of 15 January 2009. This is launched about 27 minutes in, marking the shift to what Kristin calls the Complicating Action section of the plot. We’re shown Sullly’s arrival at the airport, the assembling of the passengers, and the takeoff. Soon enough, a flight of birds hits and the plane is damaged. Sully and copilot Jeff Skiles radio the air control center.

At this point, our attachment shifts to the controllers, and we hear the pilots trying alternative options. Other aircraft in the area see the plane go down, and the controller is relieved to learn that the landing was successful.

Crucially, we aren’t in the cockpit throughout this first run-through of the landing. Although the film celebrates Sully, the narration initially shifts our attachment to others trying to help him. This tactic also allows the filmmakers to save the most dramatic version of the landing for later replay.

The second major flashback, triggered by Sully brooding in a pub, shows the rescue operation. There’s a replay of the plane’s descent, again refracted through observers. Some are eyewitnesses, but mostly we see coast guard people who leap into recovery mode.

We alternate those views with vignettes of the passengers evacuating, overseen by Sully’s apprehensive effort to make sure all survive. Even after the passengers have been taken aboard the rescue boats, Sully can’t calm down until he’s told that the tally shows that everyone is safe.

The end of the flashback, which I’d say constitutes the Development section in Kristin’s model, introduces the crucial motif of timing, which will be Sully’s defense at the last hearing.

We’ve registered the water landing from the perspectives of the air-traffic controller, of eyewitnesses on the ground, of the first responders, and of the passengers. But what were the 208 seconds like inside the cockpit? This will be the business of the film’s climax, and several versions of it will be presented.

At the final hearing of the NTSB, a public one, the Board members report on the computer simulations. Those indicate that the plane could have flown back to La Guardia or on to Teterboro for a safe landing. Then the Board, through video contact, shows pilots simulating the alternatives, instant by instant starting from the bird strike. These reenactments are a bit like Sully’s nightmare and daytime fantasy, in that they present grim alternative scenarios—hypothetical replays, we might say. Both confirm the computer’s conclusion that the water landing wasn’t necessary.

A fair amount of suspense has been built up by these reenactments. The audience hasn’t seen everything that happened in the cockpit during the crisis. How can these simulations be challenged?

Sully raises the crucial point that the pilots in the simulation had foreknowledge of what they were to do. (In cognitive-science jargon, they were primed.) In fact, the Board admits, the pilots were permitted to practice the maneuver several times. Sully requests that time be added to the simulation, as a way to reflect the real conditions of unexpected decision-making.

So the pilots run the simulations again with a 35-second lag. Both the La Guardia and Teterboro options now lead to crashes. Sully and Skiles are vindicated. Finally, we get a full-blown replay of the critical action in the cockpit, thanks to the Board’s playing of the flight-box recorder. We hear the pilots’ conversation while the film flashes back to show Sully and Skiles facing the crisis.

Thanks to editing, the 208 seconds from “Birds!” to safe landing gets expanded a little in this replay. (By my count, it runs about 330 seconds.) And we aren’t wholly confined to the cockpit visually, as we can trace the plane’s progress from outside. Basically, though, we’re attached to the two men, sometimes through optical POV shots. Although we saw the early phase of the pilots’ routine safety responses in the first long flashback, now we see the whole process, culminating in Sully’s decision to land on the Hudson.

What might have been a strenuous exercise in padding, replaying the crucial moment just to stretch the action out, becomes a strategic way to balance individual and collective effort. The first two long flashbacks stress the roles of the air-traffic controller, the crew, the passengers, and the first responders. In this respect the heroism is spread out, showing a collective effort to save the situation. Only at the climax does the film confirm what many witnesses have said from the start—that Sully deserves to be called a hero. The NTSB officials pay tribute to him as the x-factor, the crucial figure in the equation. But he demurs: “It was all of us.” The theme of group accomplishment is made tangible by the film’s play with plot structure and narration.

The replay flashback wasn’t unknown in silent film, and sound examples include The Canary Murder Case (1929) and The Witness Chair (1936). Nevertheless the replay becomes quite elaborate in the 1940s, with Mildred Pierce (1945) being a particularly intricate example. It’s clearly an idea circulating through the filmmaking community: Cukor wanted a replay for A Woman’s Face (1941) and Mankiewicz wanted one for All About Eve (1950). (He got one in the self-produced Barefoot Contessa, 1954.) An almost fussy example can be found in the British flashback film, The Woman in Question (1950). Since then, the replay has been a rich secondary resource for Hollywood. Its widespread revival, and repurposing, in modern cinema reminds me of a remark made by André Bazin.

Sometimes Bazin’s reference to “the genius of the system” is taken as praise for the Hollywood studio system as an economic enterprise. I don’t read it that way. I think he was referring to the fecundity of a particular storytelling tradition.

The American cinema is a classical art, but why not then admire in it what is most admirable, i.e. not only the talent of this or that filmmaker, but the genius of the system, the richness of its ever-vigorous tradition, and its fertility when it comes into contact with new elements.

Bazin gives as examples of such “new elements” the commentary on American society to be found in films like Bus Stop and The Seven Year Itch. In such films, “the social truth . . . is not offered as a goal that suffices in itself but is integrated into a style of cinematic narration.” Sully does much the same thing. Seizing on the bare incident of Captain Sullenberger’s landing and its reception by the public, the filmmakers have integrated it into a narrative pattern that is at once traditional and novel.

It’s this interplay of narrative convention and innovation I try to trace across a single period in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The citation of Bazin comes from “On the politique des auteurs,” in Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 258.

I discuss network narratives in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 9-103, and more extensively, drawing examples from world cinema, in “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 189-250. On this site, see this entry on Grand Hotel (1932), this one on Life without Principle (2011), this one on some examples from the 2000s, and another about Babel (2006). One from last winter compares network narratives to films with one or two protagonists. See also Peter Parshall’s book Altman and After (Scarecrow, 2012). Want to see a combination of network narrative and maniacal replays? That would be Vantage Point (2008), which I once intended to write about here before a trip to Asia deflected me. . . .

To-camera address in The Wolf of Wall Street is considered here. In another entry I discuss traces of the would-be replay in All About Eve. “Play It Again, Joan” considers purely auditory replays. To compare a replay with a film’s first iteration, you can check my analysis of Mildred Pierce and the video therein. I discuss a pseudo-replay in The Chase (1946); it’s weird, but that’s the Forties for you.

Other examples of modern assimilations of 1940s techniques are discussed in this entry on fragmentary flashbacks and this entry on Tarantino. And of course there’s the labyrinth of linkages we find in The Prestige. For other relevant entries, check the category 1940s Hollywood.

Jersey Boys.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Narrative strategies, Narrative: Suspense |  open printable version

| No Comments » open printable version

| No Comments »

Sunday | September 18, 2016

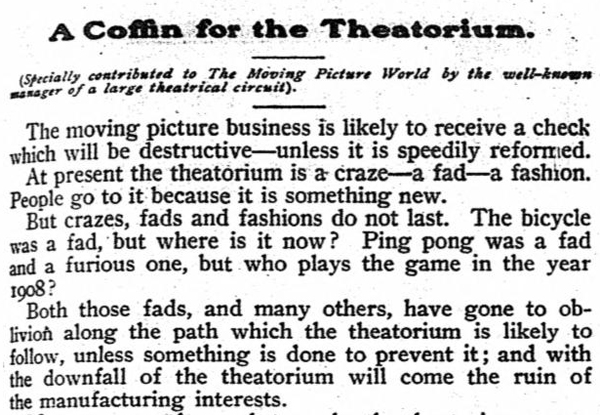

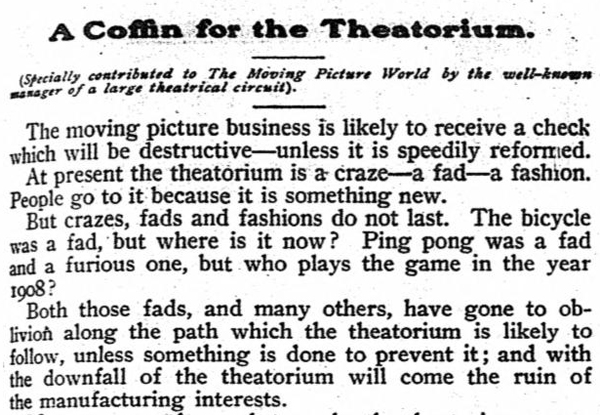

Moving Picture World (February 1908), 135.

DB here:

Vis-à-vis the last post, all of three hours ago, Alert Reader and arthouse impresario Martin McCaffery sends the above.

Actually, it’s much in the spirit of current jeremiads: Movies and their theatoriums better shape up, or they’ll be finished–like bicycles and Ping-Pong.

History is so cool. Full text here and below. There’s also a 1908 rebuttal, in the spirit of movies-are-doing-just-fine-thanks, here. Both courtesy the prodigious Lantern.

Posted in Film criticism, Global film industry, Hollywood: The business, Internet life, Movie theatres |  open printable version

| No Comments » open printable version

| No Comments »

Sunday | September 18, 2016

Our Little Sister (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2015).

DB here:

The perennial Silly Season topic, The Death of Film, is back.

In June, Huffington Post‘s Matthew Jacobs announced “The death of Movies As We Know Them.” He laments the loss of “solid storytelling and bankable stars.” In August, Brian Raftery asked: “Could this be the year that movies stopped mattering?” The author argues that now movies are “Something to Do When the Wi-Fi’s Down.” Echoing the virality theme, Ty Burr announced that two albums, Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and Frank Ocean’s “Blonde,” “came packaged with better movies than anything in theatres.” For Burr, the summer season confirmed that audiences are more interested in grazing among YouTube clips and luxuriating in eight-hour video serials than watching a feature film. “The two-hour movie, especially in its larger and more commercial form, is becoming a relic.”

Richard Brody eloquently replied to Raftery, noting Beyoncé’s debt to Julie Dash and Khalik Allah’s films. Brody has been around this block before, as I noted in a 2012 blog entry.

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

But after four years, maybe things really have deteriorated. So let’s get specific. What’s really going down the tubes? The theatrical side of the industry? Quality? Cultural cachet?

Movies, your best entertainment value

Bar area of Orange Cinema Club, Beijing.

Let’s look at some current evidence about the industry, thanks to the redoubtable Cinema research division of IHS Media Technology.

The newest symptom of cinema’s demise, according to many, is the rise of Netflix and other streaming platforms. Serial TV is attracting a lot of attention, true, but streaming has long relied on licensing feature films from studios, independents, and overseas companies. TCM and Criterion are launching FilmStruck as a new channel chock-full of classic films from Hollywood and elsewhere. Amazon and Netflix have also begun acquiring and financing features to guarantee a supply of those two-hour films that for some reason people still want to watch.

But what about movies in theatres? Actually, things are pretty robust. Despite everybody viewing at home and on the go, for many years theatre growth has been phenomenal. In 2015 the world added about 12,000 screens, hitting a new high: 153,163. Not counting all our “second screens” (and third), there are more movie screens now than ever before.

By the way, those of us, me included, who worried that the rise of digital exhibition would cause a drop in screens were wrong. Digital was a shot in the arm to theatrical exhibition, and it made 3D a viable platform. That format shows signs of growth, chiefly because of China, and now 16-20% of box-office grosses come from 3D screenings.

In keeping with the expansion of exhibition, for the last decade, the global box office has risen steadily. Almost every year sets a record. The new height is $37.7 billion for 2015, and it seems likely that 2016 will beat that.

As for number of admissions, 2015 also set a record: 7.4 billion, a jump of 13% over 2014. This is a bit more than one ticket for every man, woman, and child on earth. The first half of 2016 is ahead of the same period last year.

Of course revenues don’t equal profits. Jacobs is especially concerned that some big films have been losing money in their domestic theatrical run. But most films lose money in that run. For a long time, ancillary markets (DVD, overseas cable, merchandising, etc.) made up for the deficits. More and more, overseas theatrical is helping in a big way. In a recent rundown, of the summer’s top twenty hits, a print story in The Hollywood Reporter indicates that foreign grosses outweigh US/Canadian ones in most cases, and sometimes by a lot.

For example, big as Captain America: Civil War was in the US, 65% of its $1.1 billion haul was due to the offshore market. X-Men: Apocalypse got half a billion theatrical, 71% of which came from the international audience. Ancillaries will still need to kick in, given the mammoth budgets of films like these, but those ancillaries piggyback on theatrical visibility. As ever, the big pictures pay for a lot of lesser films.

Moreover, so many costs are buried or dispersed in overhead, debt service, tax incentives, deferred payments, far-fetched studio expenses, and the like that it seems hard to know what final profits really are. Nor will we know what, if any, profits are yielded by films from countries with subsidized film industries.

There are many things to worry about in the exhibition business, but it doesn’t seem on the verge of collapse. Let’s keep a sense of proportion. Here is what the death of “our cinema” might really look like.

Theatre admissions fall 45% over six years. Studio profits fall 80% over the same period. One-sixth of theatres close. Major overseas markets refuse to remit the earnings of Hollywood films. Audiences turn increasingly to other leisure activities.

This was the state of the American film industry in 1953. The prosperous war years, culminating in the all-time admissions high of 1946, were over and the studios went into sharp decline. Thanks to the 1948 Supreme Court “Divorcement Decree,” the studios lost control of their theatres, relinquishing not only valuable showcases for their product but also millions of dollars of prime real estate.

Yet as we know, 1953 didn’t end cinema, not even American cinema. As the old studio system waned, a new one eventually replaced it. In the process, Hollywood continued to make major films. Filmmaking abroad—in Asia, Europe, and South America especially—flourished. Film festivals sprang up, and a new young public proved eager to watch movies from a variety of cultures. Avant-garde and documentary movements gained traction, partly because of the widespread dissemination of 16mm.

No one, so far as I can tell, predicted the end of cinema, or Hollywood, because of the 1947-1953 crisis. That person would have looked very foolish. Things today aren’t nearly so severe.

Long, hot summers

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history. What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

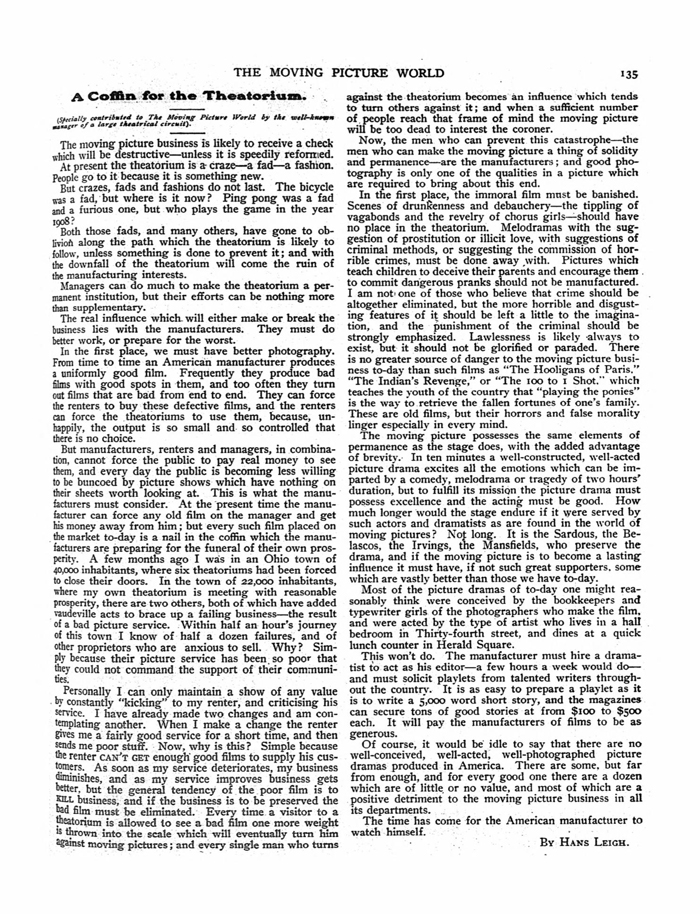

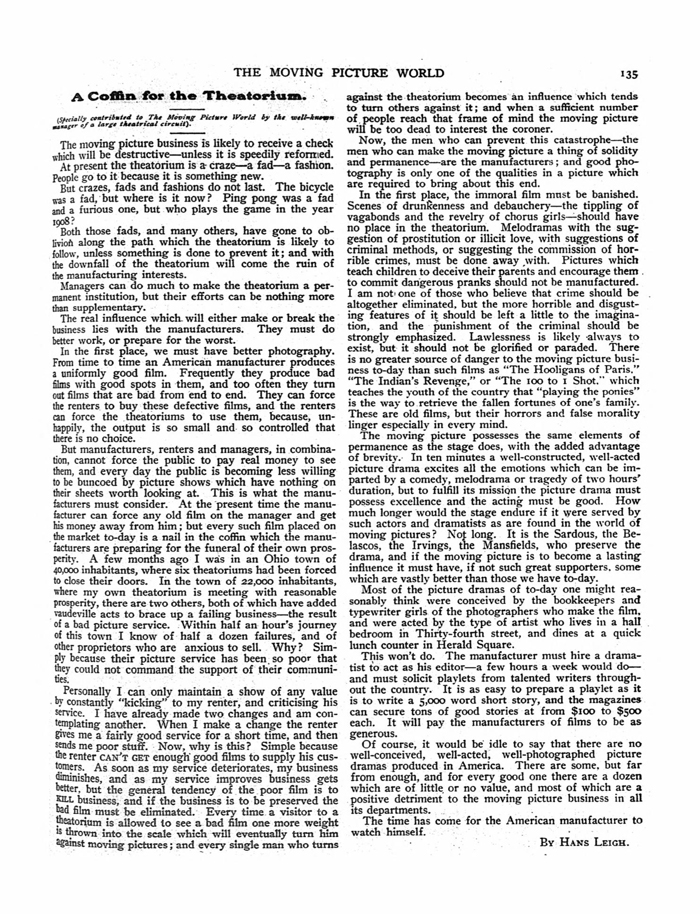

Things often seem grim at summer’s end. Let’s go back fifty years, to the summer of 1966. In those days, the blockbusters and prestige pictures were saved for fall and winter. Indeed, the blockbusters were largely the prestige pictures, the adaptations of novels and plays. The big grosser of the year was Hawaii, released in October. Two others were The Bible: In the Beginning (September) and A Man for All Seasons (December). But two of the top-grossers hit the jackpot in the summer: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (July) and Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN (June).

Pause on this last title. Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN was an indisputably lowbrow hit, a Disney comedy starring Dick Van Dyke. The fact that it earned $10.1 million (about $75 million today) might well have set critics worrying about American tastes. Worse, they might have concluded there was no hope, because from 1950 to 1970, twenty Disney films appeared in the annual top five. That record includes not only animated classics but In Search of the Castaways, That Darn Cat, and Darby O’Gill and the Little People–enough to make intellectuals despair of American moviegoers. Robin Crusoe‘s summer success might have seemed another sign of End Times.

Summer 1966 also saw The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, Fantastic Voyage, the remake of Stagecoach, a Bob Hope comedy, the low camp of Batman, and the high camp of Modesty Blaise. The 1966 counterpart to our spate of superhero sagas was a cycle of spy movies, somber or spoofy. The summer yielded Blindfold, Arabesque, and even The Man Called Flintstone. Along with these came Nevada Smith, Khartoum, What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?, This Property Is Condemned, and Wild Angels.

Some of these are well-remembered, mostly by viewers exposed at an impressionable age. For prestige there was and remains Virginia Woolf. For auteurists, there was Three on a Couch and Torn Curtain, and perhaps Modesty Blaise. As for the rest, most were and are still decried as junk.

Things were not looking good for American cinema. The Sound of Music had just won the Best Picture Oscar, a middlebrow shot across critics’ bow, and Pauline Kael was turning angry firepower on the massive threat posed by The Singing Nun. In the summer, the Times lambasted Hitchcock and Jerry Lewis. As far as I can tell, the follow-ups to the Bond boom pleased hardly anybody.

In sum, we forget just how godawful summer movies can be, year in and year out. The few we remember after Labor Day bob up from a river of sludge. We should be grateful for Indignation, Finding Dory, Lights Out, The Shallows, Hell or High Water, Don’t Breathe, The BFG, Kubo and the Two Strings, and probably half a dozen others I haven’t seen. (But not Jason Bourne, which I have.) Ben-Hur wasn’t as terrible as I’d been led to believe.

And of course, everybody’s pumped for the fall, for Snowden and The Arrival and The Birth of a Nation and La La Land and Manchester by the Sea and all the rest. 1966 critics were looking forward as well, but to what? Not only Hawaii, The Bible, and A Man for All Seasons but also Is Paris Burning?, Grand Prix, Any Wednesday, The Sand Pebbles and more spy movies (Gambit, The Quiller Memorandum). Not so exciting by our standards; Big Pictures were more square then.

True, also coming up in the fall of ’66 were The Fortune Cookie, Seconds, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Fahrenheit 451, The Professionals, Loves of a Blonde, and Blow-Up. But even then some critics stayed unhappy. Kael denounced Blow-Up, and Vernon Young intoned: “The party’s over. . . . Another phase of film history, in many ways the most creative, is drawing to a close.” Sound familiar?

Conversation starters and stoppers

End-of-movie writers argue that pop music and Quality Television are usurping the cultural place of film. But I’m skeptical, because I don’t think film is playing in the same arena.

Odd as it sounds, film has never been popular on the scale of other mass media. Before TV, radio listeners far outnumbered film audiences. Via radio and records, a hit tune reached more people than nearly any movie. Even today, radio audiences are surprisingly big. Nielsen reported in 2014 that just in the 18-35 age group, 65 million people listen to radio broadcasts each week. That’s nearly three times the average number of all viewers who attend movie theatres in a week.

Once TV came along, it became another truly mass medium. 73 million people, over a third of the US population, watched the Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964. TV is still the big game. More than 20 million people watch The Big Bang Theory each week. It’s reported that 8.9 million people watched the season finale of Game of Thrones in original cablecast, and 23 million in all its iterations. Yet, again, about 23 million people see all the movies playing in a given week.

The plain fact is that visiting a theatre to see a movie has been, throughout most of American history, a middle-class pastime. It’s relatively expensive, and getting more so. It’s not quite niche, not as rarefied as theatre or concert music or novels, but still not on the scale of other media. We ought to expect that memes will spread faster and more pervasively in pop music and television platforms.

Our critics are concerned that films aren’t part of what Raftery calls “the pop-cultural conversation.” “What in popular culture got people excited or even interested over the last few months?” asks Burr, going on to worry that movies didn’t do so. This is a strange criterion for judging films. Hula hoops, Rubik cubes, Chia pets, and Donald Trump’s coiffure have all been part of the cultural conversation. Some good films excite lots of people, and some don’t (partly because those people don’t know of them). And of course many people got excited by films Burr and Raftery considered bad, like Suicide Squad. Excitement may not be a great standard for excellence.

The cultural-conversation gambit suggests that mere popularity needs to be accompanied by a special jolt, the hum of nowness, the throb of hipness. Financially successful films like The Jungle Book or Finding Dory don’t give off much buzz. Where does that special ingredient come from? Apparently, now, the Netizens. It’s natural that critics, who are assigned to surf the waves of mass tastes, would identify important art with what’s trending on Facebook. It’s their job to hop on what’s hot.

Or in truth, help make it hot. When critics treat what’s buzzy as valuable, they agree with marketers, and cooperate with them. How many critics who loved The Dark Knight had been prompted by the campaign that played up “Why So Serious?” and other memes that publicists thought would stick? Kristin has documented how The Lord of the Rings marketers set the agenda for journalists by means of junkets and Electronic Press Kits (above), while wooing fans with carefully judged opportunities to participate online (a “pop-cultural conversation,” for sure). The typical big film is positioned by the marketing campaign, and even unanticipated responses, especially if the film is strategically ambiguous, can feed ticket sales.

The People don’t start the cultural conversation; they react to what they’re given. The conversation is started by the studios, and they try to channel it. They generate the “controversies” about making the protagonists of Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens a woman and an African American man. The critics pick up the story. (Remember: column inches.) Viewers dutifully enter their opinions on blogs, tweets, and comments columns–which the critics then re-spin. As Brody points out of Quality TV, it’s all about expanding discourse, indefinitely. Criticism begets “comments” which beget chitchat. This is less a conversation than a perpetually chattering flashmob.

A side note: I wonder if making cultural buzz a criterion of worthwhile cinema doesn’t owe something to the influence of Pauline Kael. She sent contradictory signals on this score, worrying that audiences were too easily bought off; the industry jollied them into accepting junk as fun. But she thought that one reason to like, say, Bonnie and Clyde was the fact that it was “contemporary in feeling.” It brought into movies “things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about.”

For a moment let’s accept the assumption that worthy movies have some broader cultural impact. How could we measure that? I suggest the Tagline Test. A movie enters the culture when a line becomes instantly recognizable. At its best, the tagline applies to an immediate situation. You step into a startling new setting and tell your friend you don’t think you’re in Kansas any more. You talk about your boss making you an offer you can’t refuse. You’re bargaining and you say, “Show me the money.” TV gives us plenty of catchphrases, of course. (“You rang?” “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” “Don’t have a cow, man.” “That’s what she said.”) This is one symptom of a show’s buzziness.

When I came up with the Tagline Test, I thought it supported the doomsayers’ diagnosis. I couldn’t think of many memorable lines from films after the 1980s. Had TV taken over the traffic in catchphrases? Crowdsourcing among two fairly diverse populations came up with a big set. Here’s a sample:

Hasta la vista, baby. Houston, we have a problem. That’ll do, pig; that’ll do. I drink your milkshake. The Precious (enunciated in a high voice). With great power comes great responsibility. Stop trying to make fetch happen. She doesn’t even go here. Stay classy. That escalated quickly. The first Rule of Fight Club… 60% of the time, it works every time. Little golden-haired baby Jesus in the crib. Schwing! Coffee is for closers. King of the World! Stay alive; I will find you.

The Big Lebowski is a virtual encyclopedia of them: The Dude abides. Obviously you’re not a golfer. That rug really tied the room together. Nobody fucks with the Jesus. So too Napoleon Dynamite: Whatever I feel like I wanna do GOSH! I’m pretty much the best in the world at it.

Maybe you don’t agree that these are all equally common; I didn’t know about the Mean Girls and Napoleon Dynamite ones. But all I need to show is that recent movies have entered the “cultural conversation” quite literally. Maybe it just takes months or years for movie taglines to replicate in everyday life. Anyhow, those who want movies to get all buzzy don’t have to worry. With Oscar season upon us, the frenzy will begin. In fact it already has, with Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation.

Who’s we?

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan. In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

Still, maybe it’s time to admit that we don’t own Hollywood. Maybe we never did, but it seems clear that with globalization “our” popular cinema is becoming something else–not exactly “theirs,” but not wholly ours either. Now You See Me 2 may have attracted only mild interest here: little cultural chitchat, except maybe among magicians, and $65 million box office (less than Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN). But it garnered $266 million internationally. Nearly a hundred million of that came from China, perhaps partly owing to long stretches set in Macau and short stretches featuring Jay Chou Kit-lun. And the director was Asian-American Jon M. Chu.

Now Lionsgate announces a Now You See Me spinoff, a feature co-production with China that will use local stars. So who owns this franchise? “Us” or “them”? If it disappoints us and pleases them, how does that mean that movies are so over? Maybe other countries’ cultural conversations are pulsing with talk of the Four Horsemen (one of whom is a woman).

It’s long been obvious that other film industries create their own versions of Hollywood. Europe, India, and Hong Kong have done it for decades. Current Chinese hits borrow from “our” rom-coms, action pictures, and comedies. In Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s The Mermaid, you can watch a blockbuster premise coming unglued. It’s a mixture of sentiment, message, slapstick, and bad taste; Hollywood twisted up in Chow’s characteristic funhouse mirror.

This won’t stop. One of the most astonishing and puzzling facts of contemporary cinema gets almost no press, maybe because it contravenes the death-of-film narrative. Over the last ten years, there has been a huge rise in the number of feature films.

In 2001, the world produced about 3800 features annually. The number passed 4000 in 2002, passed 5000 in 2007, and passed 6000 in 2011. In 2014, IHS estimates, over 7300 feature films were made in the world. There are now fifteen countries that produce over 100 features a year. As a result, only 18% of the world’s features come from North America. The boom took place despite the rise of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. And it happened despite the fact that American blockbusters rule nearly every national market. This may be a bubble, or it may be genuine growth. In any case, we ought to investigate the reasons that a great many people around the world stubbornly persist in making two-hour films. They don’t appear to care if We sense a summer slump.

While I was preparing this entry, Kristin and I went to Our Little Sister, Kore-eda Hirokazu’s 2015 film about three sisters abandoned, first by the father, then by their mother, and raised by the moderately stern oldest sister. The plot follows what happens when the trio takes in their half-sister after her mother dies. This is a movie that’s bereft of villains and almost totally lacking in conflict. The sisters’ misjudgments and flaws cause them problems, and sometimes they quarrel, but mostly we see decent people trying to lead happy lives, and largely succeeding. Compared to Kore-eda’s debut, Maboroshi (1995), it’s pictorially rather conventional. (That damn sidling camera.) But its episodic, open-textured plot, its quiet depiction of changes across seasons and years, and its casually serene vision of family and community make it one of the most enjoyable and moving films I’ve seen this year.

Based on the graphic novel Umimachi Diary, the film participated in Japan’s “cultural conversation.” It’s certainly a mainstream commercial movie, of a sort that Japanese studios have turned out for decades. It won solid attention on the festival circuit too. It earned a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, up there with Kubo and Hell or High Water. But such a reserved, sentimental film will never get the edgy buzz that our doomsayers want. Sentiment, after all, is anathema to our dominant mode of consuming pop culture, that of cool, ironic knowingness.

I don’t want to oversell Our Little Sister: Kore-eda is no Ozu. But this film and many others remind us that worthwhile films are still made, and released, and available outside the circus tent of Entertainment Weekly cover stories. (In this case, Americans’ thanks should go to Sony Pictures Classics, now celebrating its 25th anniversary.)

In short: Forget the zeitgeist; it likely doesn’t exist, apart from marketers’ dreams and journalists’ deadlines. Forget the cultural conversation; there’s not only one. Seek out the films that matter to you, and not “to us.” Stay classy!

Thanks to correspondents on two listserves, that of Communication Arts film folk and that of the Art House Convergence. A great many people made many suggestions, with the inevitable duplication, so thanking everyone by name would be protracted. But you know who you are.

My information on worldwide production and exhibition comes from issues of IHS Media & Technology Digest and Cinema Intelligence Report. Special thanks to David Hancock, Director of IHS Cinema division. Pamela McClintock’s “Summer Anxiety Despite Near-Record Numbers” in the 16 September Hollywood Reporter print edition contains the top-twenty film list I mention; that chart isn’t included in the online version.

On the summer 1966 US releases, see The Film Daily Yearbook of Motion Pictures 1967 (Film Daily, 1967), 144-168. I charted the year’s top-grossers from Susan Sackett, The Hollywood Reporter Book of Box Office Hits (Billboard, 1996).

My quotations from Pauline Kael come from her Bonnie and Clyde review reprinted in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1968), 47. My quotation from Vernon Young is the opening of his “The Verge and After: Film by 1966,” in On Film: Unpopular Essays on a Popular Art (Quadrangle, 1972), 273.

It’s probably irrelevant to mention that both Scorpio Rising and The Brig were released, in some sense, in summer 1966.

P. S. 18 September 2016: And see the practically real-time followup. Remember when blogs were like Twitter is now?

12,000 tickets are sold for premiere screenings of Baahubali (2015) in Hyderabad, India.

Posted in Film comments, Film criticism, Film industry, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Hollywood: The business, Readers' Favorite Entries |  open printable version

| No Comments » open printable version

| No Comments »

|