Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic

Staging

[1] Introduction

[2] Revising Our Sense

of Feuillade

[3] Mizoguchi the Inexhaustible

[4] Cheerful Staging: Hou’s

Early Films

[5] Staging and Stylistics:

Some Further Business

[6] Misprints, Mistakes, and Missed

Opportunities

Mizoguchi the Inexhaustible

Preparing this sidebar for Figures Traced in Light, I

can’t help but recall a fall day in 1969. It was then that I

came out of the old Bleecker Street Theatre in Greenwich Village,

tears pricking my eyes. Sansho the Bailiff struck me

with an impact it retains on every viewing; sometimes I feel that

I shouldn’t watch it again, for fear that its lustre will

dim. It’s a wonderful film to see in your early twenties,

based as it is upon the painful ties to your home and the sense

that going into the world can soil you forever. (Why is it named

after him? I always ask my classes. Isn’t it a bit like

changing the title of Othello to Iago? My own

view is that for Mizoguchi the world we live in, unhappily for

us, belongs to its bailiffs.) A couple of years later I would see Chikamatsu Monogatari, Ugetsu, Life of Oharu, and Street of Shame. By the late 1970s, I

was convinced that Mizoguchi was one of the masters of world

cinema.

Indeed, you could make a credible case that the two greatest

directors in the history of film were both Japanese. Ozu Yasujiro

and Mizoguchi Kenji are opposed in many respects; for one thing,

Ozu has a rich sense of humor and Mizoguchi displays virtually

none. But both understood that cinema is at once a narrative,

performative, and pictorial medium, and they explored all three

dimensions. Their explorations were highly original, while

remaining deeply indebted to tradition. In Ozu and the

Poetics of Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1988), I

tried to show that Ozu’s work is a thoughtful effort to build

a stylistic system that had the rigor of the mainstream

continuity style but that permitted a range of more nuanced and

playful effects. Chapter 3 of Figures Traced in Light paints Mizoguchi as a more eclectic artist. I emphasize his

visual side while also trying to show how his pictorial

intelligence affected his storytelling and his conception of

performance. In the following reflections I trace out some issues

I didn’t pursue in the book. I’ve had to restrain myself,

for I’d love to examine in detail virtually all his films.

For the student of cinematic artistry, his work is

inexhaustible.

A Master of Editing?

Critics have rightly celebrated Mizoguchi as the supreme exponent

of the long take, but his early work displays a command of most

of those resources of editing that emerged in world cinema during

the 1920s. As my chapter indicates, his earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays thorough knowledge of the

continuity system promulgated by American cinema. Like his

contemporaries, Mizoguchi made effortless use of the 180-degree

system, eyeline matching, matches on movement, cuts linking

adjacent spaces, point-of-view shots, and all the other editing

devices we associate with mainstream commercial cinema of the

period. No long takes of the sort we’ll find in his

1930s silent films are evident in Song of Home.

Instead, Mizoguchi here enlists in the tradition of what I’ve

called “piecemeal decoupage,” the analytical approach

characteristic of the contemporary-life films

(gendai-geki) made at the Shochiku studios. Like Ozu,

Naruse, and other exponents of this style, Mizoguchi varies his

shot scales a bit more than an American would. For example, when

the scholar offers Naotaro a reward for saving his daughter, no

setups are repeated across the five shots.

- (plan-americain) The scholar offers Naotaro some

bills.

- (close-up) Bills in the scholar’s hand.

- (ms) Naotaro and friend, three-quarter view.

- (ms) Naotaro’s point of view: the scholar extends the

money to the camera.

- (mcu) Reverse angle: Narotaro looks at the money extending

into the shot.

Fig. 3A.1

Fig. 3A.2

Fig. 3A.3Still, if we’re looking for a prefiguration of

Mizoguchi’s later work, this film exhibits cutting patterns

that show a sensitivity to foreground/ background

relations.

In the climactic scene, when the professors come to Naotaro’s

house to offer to fund his education, Mizoguchi covers the entire

scene in thirty-eight shots (plus eight intertitles), and

although some setups are repeated, there is a delicate variation

in the framings, each of which brings different dramatic elements

to our notice. We start with the overall ensemble (Fig. 3A.1),

eventually move to Naotaro flanked by the two educators (Fig. 3A.2), before reaching the climax, showing Naotaro and his mother

and sister behind him, as he declines to leave the countryside.

“Getting an education is good, but I must be a farmer who is

independent and self-aware” (Fig. 3A.3).

Other editing trends were at play in world cinema of the 1920s,

and Mizoguchi seems no less aware of them. French, German, and

Russian directors, as well as some U.S. filmmakers, experimented

with rapid cutting, made rhythmic by increasingly brief shot

lengths. This tactic was also pursued in Japan, particularly by

directors working in the swordplay genre (chanbara).

It’s likely that some of Mizoguchi’s lost films would

bear traces of this influence, but even in the condensed version

of Tokyo March (1929) we can glimpse this tendency in a

fast-cut tennis match. A similar moment of visual rhetoric

appears in The Poppy (1935), when Ono, walking the

street with his sweetheart, encounters the wealthy young woman

who’s out to seduce him. Their encounter is played out in a

flurry of very short shots:

- Ono and Sayoko talking; she runs into close-up.

- Low angle: After Sayoko nearly bumps into a rickshaw, Ono

steps up.

- (ms) Ono looks right. (25 frames)

- Reverse-shot: Fujio in the rickshaw, stares. (15

frames)

- (ms) Ono, as 3, still looking. (13 frames)

- Fujio, as 4. (39 frames)

- (ms) Ono and Sayoko, looking. (35 frames)

- Slight jump cut: Ono looking, as 5. (13 frames)

- Fujio, as 6. (11 frames)

- All three; after a pause, Fujio orders the driver to

continue. Ono and Sayoko stare after her.

The accelerating/ decelerating editing, reminiscent of Feuillade

in our the webpage extract from L’Orpheline, is a

good example of the sort of visual flourish that was common in

silent cinema. It was infrequent in the mature sound cinema,

though we can find it in Hitchcock’s work and in

Hollywood’s “montage sequences” of the 1930s and

1940s. This rhythmic editing scheme recurs in several films of

the 1960s, e.g., A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and the

climax of The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (1966).

Fig. 3A.4

Fig. 3A.5

Fig. 3A.6Such editing flourishes are also on display in Taki no

shiraito (White Threads of the Waterfall, 1933), in

a swift montage that inserts pulsating flashbacks to a coach ride

into a scene showing Taki making up for a performance with. No

less impressive is the climactic courtroom scene. Taki faces the

judges, one of whom is the young man she has supported through

law school. My chapter points out that there are some forty-five

camera setups for the scene’s eighty-five images, and I

indicate the remarkable way that Mizoguchi creates dramatic

impact through insisting on rapidly cut singles of Taki and her

judges, with tight depth-composed close views (Figs. 3.19 and 3.20,

p. 100). The whole effect is reminiscent of Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928). And despite the

film’s frequent long takes, Mizoguchi can always spare a

moment for a very creative cut, as when after Taki has begged Kin

to save her, they pass to the bars of her cell. Amid several

aperture framings (for example, Fig. 3A.4 (right); compare Figs.

3.116 and 3.117 in the book, from Sansho the Bailiff), Mizoguchi

gives us a startling graphic match showing the two of them in

similar positions, the slats maintaining the aperture conceit

(Figs. 3A.5 and 3A.6).

On the evidence we have, it doesn’t seem that Mizoguchi

simply went from being a cutting-based director to being a

staging-based one. The fancy cutting just mentioned occurs in

films that also rely on long takes and ensemble staging. It seems

that for a time he held both approaches in balance (as Welles did

in Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Othello, and Touch of Evil). In the surviving

films from 1936 to 1941 Mizoguchi favored staging-based effects,

but after the war he resumed the pluralistic approach seen in the

earliest surviving films. Audacious though his editing

occasionally was, he didn’t construct an alternative,

full-bodied system as Ozu did over the same period.

The Love of Sumako the Actress (1947)

This remarkable film, as I note in the chapter, recalls the

daring experiments in depth and darkness Mizoguchi undertook in Naniwa Elegy and Story of the Last

Chrysanthemum. It might be regarded as his last effort in

this direction before moving toward the flexible, pluralistic

style of his last decade.

Mizoguchi’s audience would have recognized Matsui Sumako as a

scandal-plagued celebrity. Between 1912 and 1919 she and her

mentor-lover Shimamura Hogetsu helped create modern westernized

drama in Japan (shingeki), and her tours and recorded

songs made her a household name and the prototype of the free

woman. Shimamura’s associates often portrayed Matsui as an

unsophisticated prima donna who lured the weak-willed director

away from his wife and children. (See Phyllis Birnbaum, Modern Girls, Shining Stars, the Skies of Tokyo: 5 Japanese

Women [New York: Columbia University Press, 1999], pp. 1 to 52.) But Mizoguchi wanted Yoda’s script to present her as

“feminine and sympathetic,” displaying “the

psychology of a modern woman” (quoted in Yoda Yoshikata, Souvenirs de Kenji Mizoguchi, trans. Koichi Yamada,

Bernard Béraud, and André Moulin [Paris: Cahiers du

cinéma, 1997], pp. 70, 74). In this he was following not

only Occupation censorship guidelines but also an alternative

view of his heroine. For many, Matsui showed that a woman could

find success in a rigid society on her own terms. Her demands,

even her tantrums, showed her supreme dedication to her art and

to Shimamura’s goal of modern theatre. This dedication,

admirers pointed out, explains why she committed suicide soon

after his death and following her triumphant portrayal of

Carmen.

At first, however, the film gives us very little access to

Sumako. One might expect that a biography of the actress would

begin with her early life, or at least the circumstances that

lead up to her joining drama school. Instead, as so often in

Mizoguchi’s films, the man’s life is presented first, and

the woman enters it. The opening scenes show Shimamura teaching,

conferring with his colleagues, and casting Sumako as Nora in A Doll’s House. The plot traces his growing

affection for her, emphasizing the damage it does to his family

and the contrition he feels. In the sequence when he leaves his

household forever, he apologizes to his wife, his mother, and his

daughter—who has lost a suitor because of her father’s

affair with Sumako. In this version of history Shimamura emerges

as no weakling, but rather a man so committed to the ideals of

modern drama, including the liberation from convention, that he

must live them outside the theatre.

The plot has a fascinatingly “staggered,” or

shifting-spotlight structure. Shimamura has the initiative in the

first eighteen sequences, and he is present in every scene except

one, when Sumako is pushed to leave her home after Shimamura

abandons his family. The result of concentrating on Shimamura is

to deny us access to Sumako’s mental life when she isn’t

around around others; we are given only one glimpse of her

dutifully studing her part. Once Shimamura starts living with

her, the narrational focus fastens on the couple, usually seen

among their theatre troupe as they struggle to find and sustain

success. Nine sequences trace their life together, and in these

scenes Sumako is shown as short-tempered but also supremely

committed—urging the actors forward, demanding a decent

rehearsal hall, accepting endless tours to pay the bills. Once

Shimamura collapses, the narrative’s focus shifts decisively

to Sumako as she confronts Shimamura’s wife and mother and

decides to struggle on.

Fig. 3A.7 |

Fig. 3A.8 |

Fig. 3A.9 |

Fig. 3A.10 |

Kinugasa Teinosuke filmed a Sumako biography at the same time

(Actress, 1947) and filled it with close-ups, but most

scenes in The Love of the Actress Sumako consist of

distant framings, often in chiaroscuro. In one daring shot, as

Shimamura walks out on his wife and mother, his departure is

barely visible in a slot just above the heads of the two weeping

women (Fig. 3A.7). In keeping with the plot’s roundabout

treatment of its heroine, Mizoguchi reserves the closest shots of

Sumako for performances or rehearsals, as if to sharpen the

difference between theatre and life. A major turning point in

this stylistic pattern occurs when, as Sumako is ill, Shimamura

gives her a ring pledging their love. The camera tracks in with

him to a medium-shot of her lying down, the closest the camera

has come to her so far; she admires the ring, then carefully

turns back to studying her text (Figs. 3A.8 to 3A.10). Even in this

intimate moment, the narration is fairly circumspect about her

affection for her lover, instead stressing her dedication to her

art. Once Shimamura has died, however, we get the first and only

scene of Sumako alone. It is handled in a manner which we

instantly recognize, but it is followed by a shot-change which,

in the context of this film, is little less than shocking.

Fig. 3A.11 |

Fig. 3A.12 |

Fig. 3A.13 |

Fig. 3A.14 |

Fig. 3A.15 |

Fig. 3A.16 |

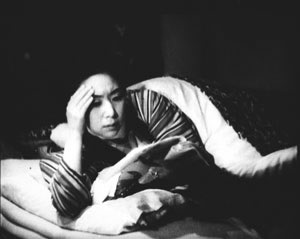

Sumako comes home from a performance and refuses to eat, sitting

disconsolately in the distant foreground (Fig. 3A.11). As so

often, Mizoguchi’s simple panning movement turns a long-shot

framing into a closer one, as she comes forward and rightward to

kneel before the memorial shrine she has created for Shimamura

(Fig. 3A.12). After lighting an incense stick, she asks how her

performance was tonight. After long pauses, she responds to his

silence by breaking down—first with her face more or less turned

toward us, then covered by her hands (Fig. 3A.13); then she curls

up in grief (Fig. 3A.14). She rises to beseech him one last time

before turning definitively from the camera and pressing into the

wall as the image fades out (Figs. 3A.15 to 3A.16). It is a typical

Mizoguchi emotional transition, from a full-face but distant view

to a closer but oblique one, until finally, as the

character’s despair reaches its height, dorsality and a

retreat from the camera take over.

Fig. 3A.17 |

Fig. 3A.18 |

Fig. 3A.19 |

Fig. 3A.20 |

As I indicate in the chapter, this moment stands in for

Sumako’s suicide, which takes place between sequences at the

end of the film. This is the most private and intense display of

Sumako’s emotions to be found in the film. True to form,

however, Mizoguchi contrasts his reticent staging with the

following shot, which presents Sumako as a turbulent, demanding

Carmen (Fig. 3A.17), challenging us full-face as Ayako did at the

close of Naniwa Elegy (Fig. 3.47 in the book). Then,

after showing us the performance in a mix of tightly composed

shots and flamboyant depth (Figs. 3A.18 to 3A.19), Mizoguchi

provides a fascinating long-take scene of Sumako’s backstage

outburst, using one of his distant-depth compositions (Fig. 3A.20). There remain only her death as Carmen onstage (another

substitute for her suicide); the discovery of her hanged body;

and her funeral. As so often in Mizoguchi, the woman enters an

already-established world of men and money, and she leaves them

behind puzzling over what she has done.

© David Bordwell 2003. [1] Introduction

[2] Revising Our Sense

of Feuillade

[3] Mizoguchi the Inexhaustible

[4] Cheerful Staging: Hou’s

Early Films

[5] Staging and Stylistics:

Some Further Business

[6] Misprints, Mistakes, and Missed

Opportunities

|

|